1. Introduction

South Korea is a rapidly aging society that will become a “super-aged” society—where more than 20% of the population is age 65 or above—by the mid-2020s [

1]. Citizens’ demands for social welfare have also increased in recent decades, and the government has responded with a rapidly increasing social welfare budget [

2]. Given that the country is about to morph into a welfare state, and a mature one at that, securing a vital, sustainable source of revenue for maintaining and expanding social welfare provisions is becoming increasingly urgent. While a tax increase can help facilitate a welfare state, it is not a simple task to move this approach from discussion to implementation. It is a particularly perilous undertaking for political actors who are supposedly more concerned about re-election than preparing a sustainable tax base for welfare state expansion [

3]. Additionally, austerity politics has been dominant in many countries since the Great Recession, with little room for a welfare state discourse [

4]. Therefore, this study focuses on (a) political trust as an explanatory variable for support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion and (b) perceived tax burden as a moderating factor in the relationship between political trust and tax increases.

We begin with a focus on political trust and its role in explaining individuals’ support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. Political trust emerged as a crucial concept in social science when its level plummeted in the 1970s, and scholars began focusing on what might explain its collapse [

5,

6]. As scholarship on political trust grew, scholars shifted their attention to its role in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward governmental policies [

7,

8]. This research emphasizes that political trust functions as a psychological signal through which individuals may support government policies, even though such policies may not suit their preferences [

7,

8]. For instance, politically conservative individuals may lend their support to liberal policies if their political trust is high, and politically liberal individuals may support conservative programs if their political trust is high [

8]. We rely on this mechanism of political trust as a heuristic to explain why individuals with a greater level of political trust may support the tax increase needed for social welfare expansion.

Next, we focus on perceived tax burden in explaining individuals’ support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. Individuals’ perceived tax burden is reshaped by various factors, an important few of which include tax complexity and tax fairness, which can negatively affect how individuals see their tax burdens [

9,

10]. When individuals perceive their tax burden as high, they experience low tax morale, which increases their tendency to evade paying taxes [

11]. Consequently, they are less likely to be motivated to support tax increases than those with a lower degree of perceived tax burden. More importantly, this study examines whether perceived tax burden plays a role in moderating the linkage between individuals’ level of political trust and their support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. As noted, individuals with a greater level of political trust exhibit favorable attitudes toward tax increases. However, political trust can be subject to various circumstances that confront individuals. Our argument is that perceived tax burden is a circumstance under which the positive impact of political trust on support for a tax increase can dissipate.

This study focuses on two aspects of explaining individuals’ willingness to pay more taxes for social welfare expansion. One is the link between individuals’ level of political trust and their support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. An unexplored area of research is that political trust can be subject to various circumstances. We argue that perceived tax burden—the second contribution of this study—can alter the influence of political trust on individuals’ support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. Thus, our study helps broaden the scope of research on political trust and enriches our understanding of how political trust operates in the world.

This study proceeds as follows: (a) we explore the importance of political trust in shoring up the tax increases necessary for social welfare expansion; (b) we discuss whether the relationship between political trust and individuals’ support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion can be altered when they find their perceived tax burden onerous; (c) we subject our research hypotheses to empirical testing, using the ordered probit and the 2018 National Survey of Tax and Benefit; and (d) we offer empirical findings and discuss their implications for policymakers.

2. Political Trust and Willingness to Pay More Taxes for Social Welfare Expansion

Political trust is a concept by which citizens evaluate the government’s performance [

12]. Specifically, it is defined as people’s attitudes toward the government’s performance based on their expectations of how it is supposed to function [

6,

12,

13]. As such, political trust combines people’s evaluations as well as their expectations of the government [

8]. Other scholars have suggested that the concept of political trust also includes the “processes” influencing performance [

7]. Some have argued that the concept should also cover government integrity, as evidenced by political scandals that have stimulated political distrust among citizens [

14,

15].

Studies on political trust took off in earnest in the wake of a series of political scandals and national crises that shook the United States. For instance, approximately 76% of Americans placed their trust in the government in the early 1960s, but that percentage plummeted to 35% in 1974 and hit the nadir at 25% in 1980 [

8]. The Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the oil crisis, the Iran hostage crisis, racial disturbances in New York, and the Iran–Contra affair sapped the public’s confidence in political actors and institutions [

16,

17]. Accordingly, earlier studies on political trust examined the determinants of political trust, pointing out that attitudinal changes, expectations, and events reshape public trust in government [

5,

6,

7]. As research on political trust began to mature, its focus shifted to what roles political trust can play in influencing individuals’ attitudes toward policy.

Scholars focusing on the influence of political trust have begun to pay attention to its heuristic function. Individuals often have limited time, energy, resources, or education to accurately evaluate a given government policy. Thus, they need a reliable tool that enables them to do so efficiently, and that is where political trust intervenes. Political trust is crucial for citizens in evaluating policies, as they often possess little knowledge of public affairs [

8]. Political trust functions as a tool and a psychological shortcut through which individuals may support a given policy, even when they are not fully aware of the potential issues, pitfalls, or implications associated with it. In short, political trust functions as a heuristic (or rule of thumb)—a mental shortcut whereby people process information quickly in an increasingly complicated world [

8,

18]. Consequently, political trust can serve as a fast-track decision heuristic to support a government program because its concept already presumes people’s satisfaction with government performance [

8]. Individuals are even willing to sacrifice their ideological or material interests because of political trust. For instance, liberals may not support a tax cut or social security privatization, but they may become more inclined to support such policies when moderated by political trust [

18,

19]. Conversely, conservatives show antagonism toward government spending on a diverse array of distributive and redistributive policies, but they may become more supportive of such policies with increased political trust [

20].

The issue of implementing a social welfare policy is becoming increasingly heated in South Korea because of its demand for government spending and the substantial burden placed on taxation. Supporting a tax increase for expanding a welfare state requires significant financial sacrifices from taxpayers. Thus, political trust works as a heuristic device that enables individuals’ willingness to sacrifice their material interests to support a tax increase for expanding social welfare. These factors suggest the following hypothesis for empirical investigation:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Political trust is positively associated with paying more taxes for social welfare expansion.

3. The Moderation of Perceived Tax Burden on the Relationship between Political Trust and a Tax Increase for Social Welfare Expansion

Although economists have traditionally assumed that human beings are rational and can accurately assess their tax burden to arrive at a maximizing economic decision, scholars have noted that perceptions of tax burden are not the same as actual, effective tax burdens [

9]. Indeed, individuals have varying notions of perceived tax burden [

9]; thus, they estimate their tax burdens differently even when they confront the same tax base or the same tax rate [

10]. For instance, when individuals were asked to assess their correct marginal tax rate, they systemically under- or over-valued it [

21,

22].

Scholars have explored a variety of factors associated with perceived tax burden [

10]. For instance, individuals’ perceptions of tax burden are shaped by factors such as tax complexity and tax fairness [

10]. Tax complexity refers to the perceptual gap between the actual tax rate and the construed tax rate [

10]-. Scholars have noted that tax complexity can be perceived differently depending on how the tax scale is presented, how the marginal tax rate is determined, how legal texts are worded, and so on [

23,

24,

25]. Complexity can also make it difficult for government administrators to identify tax evasions and to differentiate between intentional and unintentional evasion cases, resulting in a significant collection burden and costs for the government [

26,

27]. Increased perceptions of tax complexity can lead to misrepresentation of the true tax burden as well as unintended tax evasion for taxpayers [

11]. Similarly, perceived tax burden is also shaped by tax fairness. For taxpayers, a tax system is supposed to be fair and equitable because they will otherwise feel betrayed, leading to less compliance with tax codes. Tax fairness can also go beyond mere tax codes; fiscal inequity can generate a sense of tax unfairness for taxpayers [

11,

28]. Tax fairness is also related to tax complexity in that the more complex a tax system is, the likelier some people are to evade taxes, causing honest taxpayers to question the fairness of the tax system. Thus, the degree of tax fairness can affect individuals’ tax morale, leading to increased tendencies to evade taxes.

Tax complexity and tax fairness influence how individuals, as taxpayers, perceive their tax burden. When they perceive their tax burden as high, they experience low tax morale, making them less likely to be motivated to comply with tax codes and pay taxes properly. When they find taxes burdensome, a reasonable conjecture can be made that they would not feel obligated to pay more taxes than they owe. Therefore, it is expected that a greater level of perceived tax burden would be negatively associated with willingness to support the tax increase needed to expand social welfare.

More importantly, this study is centered on the role that perceived tax burden plays in moderating and weakening the relationship between political trust and support for a tax increase. What might be the theoretical mechanism behind the moderation effect of perceived tax burden? As stated above, individuals with a high level of perceived tax burden are likely to have lower tax morale and feel that paying more in taxes is unjustified. This may create a greater tendency to evade taxes than those with a low level of perceived tax burden. Within this context, a high degree of perceived tax burden would not aid citizens in their support for a tax increase and may erode individuals’ confidence in the government, leading to a lower level of political trust. Thus, political trust’s function as a heuristic device would dissipate when individuals’ level of perceived tax burden is high. Ultimately, the positive attitudes individuals with a high level of political trust would exhibit toward support for a tax increase would wane when the level of perceived tax burden was high. Given these factors, the following hypotheses can be suggested for empirical testing:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Perceived tax burden is negatively associated with support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Perceived tax burden moderates the linkage between individuals’ level of political trust and their support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion, making the relationship weaker as the level of perceived tax burden becomes stronger.

5. Results

We relied on an ordered probit model for the empirical analysis because the dependent variables possessed ordinal values. We also accounted for the weight provided by the dataset, which considered population size, and employed robust standard errors.

Table 2 demonstrates the results. Our analysis comprised two steps. The first step gave the results of the direct relationships between the explanatory variables and the dependent variable. The second step centered on the results of the moderating effects of perceived tax burden on the relationship between individuals’ level of political trust and their support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. The moderating effects were calculated by the interaction of perceived tax burden and individuals’ level of political trust in explaining individuals’ support for a tax increase.

The results confirmed our three hypotheses. First, the results accept H1. Individuals’ level of political trust was positively associated with their support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. Our reasoning for this—as stated earlier—was that political trust works as a heuristic through which individuals may support government policies, even if such policies endanger their political preferences. Studies have shown that individuals are willing to sacrifice their ideological or material interests if they place a greater level of trust in political institutions [

8,

12]. Our study confirmed these findings, demonstrating that individuals are not inclined to support a tax increase but are willing to bear the burden if their level of political trust is high. Thus, the heuristic function of political trust works in this model.

Second, the results accept H2. The findings confirmed the negative relationship between individuals’ perceived tax burden and their support for a tax increase. A perceived tax burden lowers individuals’ tax morale (i.e., their voluntary willingness to abide by tax codes and pay taxes with integrity) [

11]. Thus, individuals with a high degree of perceived tax burden are not likely to be motivated to support tax increases.

Third, the results accept H3. Our study centered on the role that perceived tax burden plays in moderating the relationship between individuals’ level of political trust and their support for a tax increase needed for social welfare expansion. The findings show that perceived tax burden has a detrimental impact on how individuals with a greater degree of political trust perceive support for a tax increase. We reasoned that individuals who perceive their tax burden as high are likely to see taxation as unfair and may feel that the government mistreats them, leading to the erosion of their confidence in the government. Thus, perceived tax burden weakens the relationship between political trust and support for tax increases in such a way that the relationship becomes negative. Perceived tax burden dampens the positive attitudes of individuals with a higher level of political trust and affects their views on a tax increase for expanding a welfare state.

In terms of controls, support for government intervention in reducing income inequality was positively associated with support for tax increases. As expected, individuals possessing a higher level of belief that the government should play an active role in equitable income distribution are likely to possess positive attitudes toward a welfare state [

30] and to support any tax increase needed to maintain and expand it. Liberals were associated with a willingness to pay more taxes for social welfare expansion [

33]. Because moderates were the reference variable omitted from the model, the results showed that liberals, at least in our data, had friendlier attitudes toward more taxation compared with moderates. Conversely, conservatives were not significantly associated with more taxation, indicating that no clear demarcation between conservatives and moderates was present in the data. Finally, the demographic variables in the model—age, gender, and educational level—were significantly associated with more taxation. The findings showed that individuals were less likely to support more taxation as they grew older; women were less inclined to support a tax increase than men; and individuals with a higher education level were likelier to support a tax increase, confirming that better-educated individuals are keen to solve major social issues and support policies that address them [

34,

35,

36,

37].

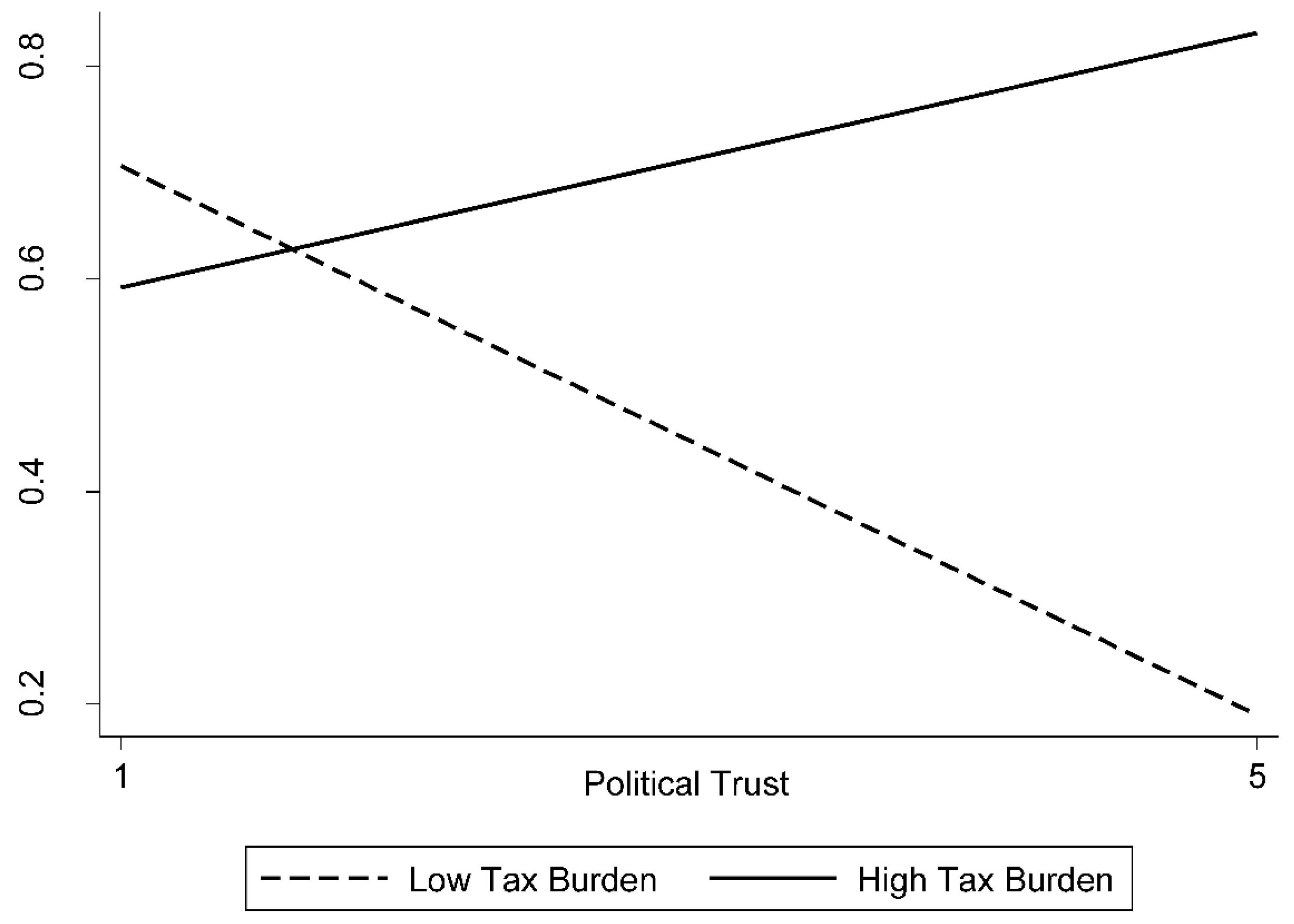

Figure 1 displays the joint effects of political trust and perceived tax burden on support for a tax increase when the level of the latter is 1 (“no more taxes”). The solid line displays the relationship between political trust and inclination toward “no more taxes” when the level of perceived tax burden is high. The slope is relatively steep and positive when the level of perceived tax burden is high, indicating that individuals are likelier to choose “no more taxes” when they perceive their tax burden as high. By contrast, the dashed line refers to the relationship between political trust and support for “no more taxes” when the level of perceived tax burden is low. The slope is steep and downward when the level of perceived tax burden is low, indicating that people are less likely to choose “no more taxes” when they regard their tax burden as low.

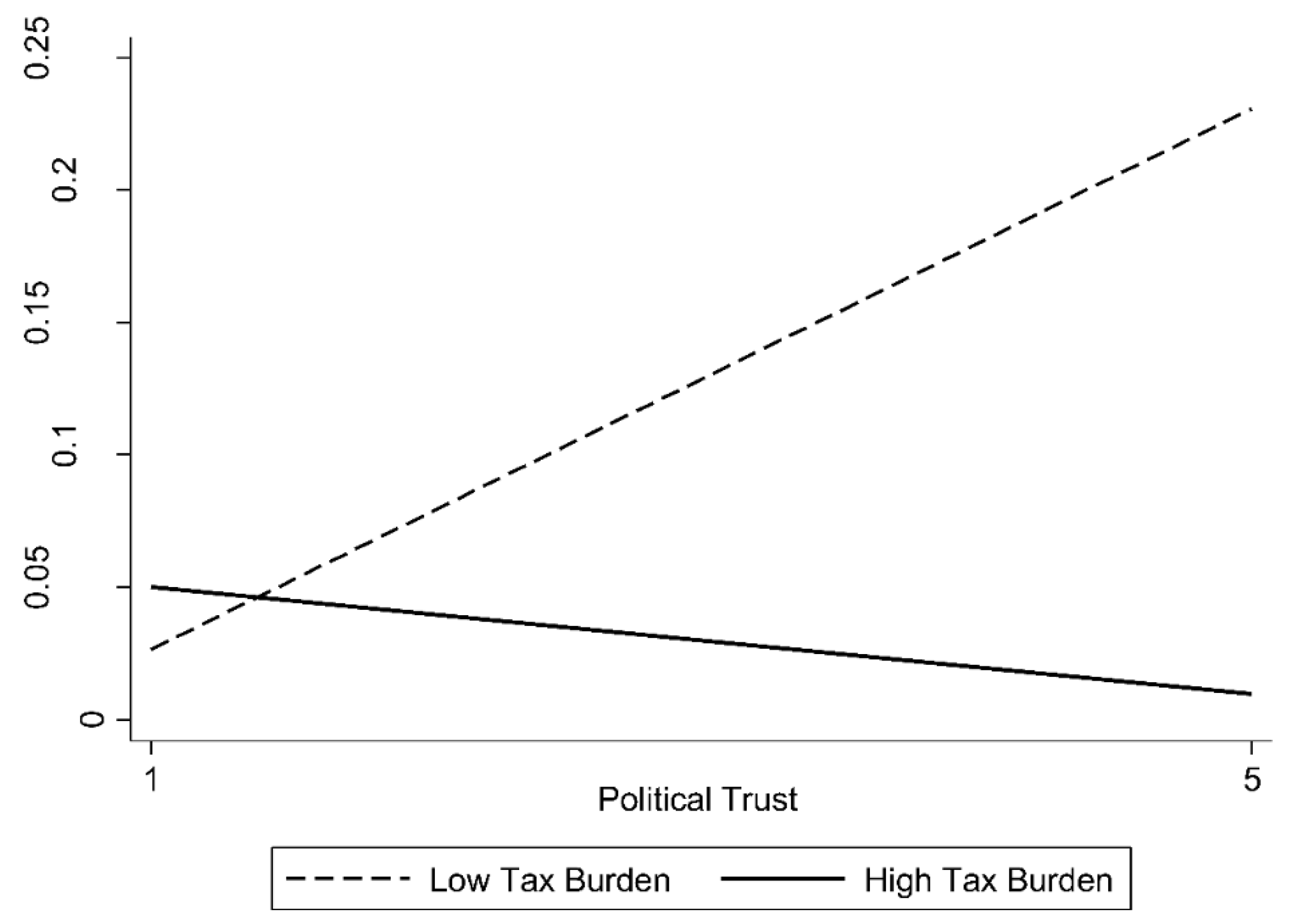

Figure 2 displays the joint effects of political trust and perceived tax burden on support for a tax increase when the level of the latter is 3 (“5–10% more taxes”). The solid line refers to the relationships between political trust and support for “5–10% more taxes” when the level of perceived tax burden is high. The slope is gradual and downward when the level of perceived tax burden is high, indicating that individuals are less likely to favor “5–10% more taxes” when they perceive their tax burden as high. The dashed line displays the relationships between political trust and support for “5–10% more taxes” when the level of perceived tax burden is low. The slope is steep and upward when the level of perceived tax burden is low, indicating that individuals are likelier to pay “5–10% more taxes” when they perceive their tax burden as low. The two graphs demonstrate the variability of individuals’ support for a tax increase when the level of perceived tax burden shifts and justifies the need to study circumstances surrounding political trust and its impact.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study have crucial implications for policymakers. Political trust is an important construct when one evaluates ordinary citizens’ attitudes toward a tax increase. As many studies have noted, political trust is vital for securing citizens’ support for a government policy or program [

8,

12,

13]. Key government decisionmakers have wrestled with identifying revenue sources for ever-expanding welfare programs that comprise a significant portion of government spending [

38]. In this regard, securing sustainable tax revenue is critical to sustaining an expanding welfare state. Our findings demonstrate that political trust is one such mechanism to help alleviate citizens’ anxiety about and resistance to a tax increase.

Citizens’ resistance to taxation has been intensifying in recent decades. The 1960s and 1970s saw a devastating array of events and circumstances—including oil embargoes, skyrocketing inflation, and welfare expansion—which sparked nationwide tax resistance for countries such as the United States [

16,

17]. Approaches like Proposition 13—constraining the taxing power of political actors by citizens’ own initiative—have emerged as manifestations of citizens’ disillusionment with taxation [

39]. Within this context, political actors have found it difficult to discuss taxation openly. After all, political actors face a short-term time horizon; they are mainly concerned about maintaining and enhancing their chances of re-election [

3]. For them, broaching taxes or a tax increase in political discourse becomes something that they avoid as much as possible. Facing deteriorating circumstances, along with political disincentives to discuss taxation, few tools are available for political actors to rely on when they consider a tax increase to meet social welfare needs and challenges. Political trust is one such tool political actors can utilize and exploit to put a tax increase at the forefront of the government’s agenda.

However, we must still consider how political actors can improve citizens’ level of political trust. As mentioned earlier, political trust reflects citizens’ evaluation of the government’s performance [

12,

13]. This dictates that political actors need to improve citizens’ perceptions of how they handle the government’s agenda, programs, and administration. Importantly, this is not necessarily an abstract idea. Sometimes, tangible events emerge for the administration to seize and reshape perceived governmental performance. For instance, the Moon Jae-in administration was embroiled in a political scandal involving the appointment of the Minister of Justice and experienced a plummeting level of citizen approval. When COVID-19 occurred, South Korea emerged as a leading country when it set a high bar for testing, tracing, social distancing, mask-wearing and allocation, and self-isolating compared to other developed or developing countries, resulting in a low death rate from confirmed cases [

40]. Voters responded to the seemingly enhanced performance by electing supermajority seats for the government party [

41]. To improve citizens’ political trust, the government must work hard to remain free of political scandals and corruption. While the outgoing South Korean administration overcame the earlier scandal through its performance during the pandemic, it has also been mired in many political scandals and controversies involving its top administrators, causing a significant degree of citizens’ political trust to vanish [

42]. Thus, while it is crucial for the government to seize opportunities when they arise to push for its desired government policy or program, it has to maintain its probity to ensure that citizens’ trust in political institutions remains high.

Our findings also demonstrated that perceived tax burden works negatively against support for a tax increase needed to expand social welfare, as well as against the relationships between political trust and support for a tax increase. Scholars have pointed out that actual tax burden is one thing, but perceived tax burden is another [

9,

10]. Indeed, perceived tax burden can be reshaped by a variety of factors. In this study, we found that perceived tax burden is mainly influenced by tax complexity and tax fairness. Thus, policymakers concerned about the weakening effect of perceived tax burden on support for a tax increase should work on simplifying tax codes and producing measures to ensure that citizens perceive taxation as fair.

To begin, policymakers need to ensure that tax codes are simple enough for taxpayers to comply with them. When tax codes are too complex, taxpayers are tempted to cheat and evade paying taxes [

24]. Additionally, complex tax codes entail high collection and compliance costs, which add financial and personnel burdens to the government [

27,

43]. Some ideas proposed to simplify tax codes include increasing the standard deduction. For instance, United States taxpayers can choose a standard deduction or an itemized deduction when they file their individual income tax returns [

44]. By simply increasing the amount of the standard deduction or eliminating itemized deductions, taxpayers do not need to juggle between the two options for better returns [

44]. Another idea is to combine tax code savings programs [

44]. By adopting some of these ideas, taxpayers will benefit from simplified tax codes and will be likelier to comply with as well as less likely to evade paying their taxes [

44].

Additionally, improving tax fairness among taxpayers requires several steps within the policy. One step is to ensure that the tax system is perceived as equitable by taxpayers (i.e., the rich pay more taxes than the poor, and collected taxes are redistributed to those in need) [

45]. Moreover, the government needs to work on eliminating loopholes [

28]. Loopholes—which are perceived to benefit specific individual groups or corporate entities—allow some taxpayers or tax-paying entities to circumvent taxes owed, generating a sense of tax unfairness. The government must also ensure that there are few tax cheats (or evasions), which are a serious business for some individuals or corporations [

37]. However, catching and penalizing people for evasions requires substantial collection costs for the government [

27,

43]. Many governments have reduced their capacity to enforce tax codes due to dwindling tax revenue, the prevalence of austerity-minded governments, or political actors who are intent on shrinking the government [

4]. When it comes to taxation, these circumstances provide tax evaders with fertile grounds to cheat when there are fewer tax enforcers [

46]. For instance, wealthy individuals have found easy opportunities to cheat by hiding their money in offshore tax havens [

47]. Furthermore, some multinational corporations have avoided paying taxes by doing business overseas [

48]. While simplifying tax codes and improving tax fairness may not solve all the problems individuals associate with taxation, these strategies will go a long way toward improving citizens’ perceptions of their tax burden.

7. Conclusions

Securing sustainable financial resources is becoming increasingly urgent for welfare states worldwide [

4]. Taxation is a vital source for buttressing welfare states. However, raising taxation is not an easy tool for governments to implement because it requires a substantial degree of citizen support. Within this context, this study explored political trust as one mechanism that explains individuals’ support for a tax increase for social welfare expansion. Additionally, our study examined whether the positive inclinations of those who possess a high level of political trust toward a tax increase for social welfare expansion are moderated and dampened by a high degree of perceived tax burden.

The results demonstrated that both conjectures were true. Individuals’ level of political trust was positively associated with their willingness to shoulder more taxes if doing so would help expand social welfare. Scholars have argued that political trust is a crucial decision heuristic that helps individuals support government policies, even though such policies entail significant ideological or material sacrifices [

8,

18]. The findings revealed that political trust functions as a heuristic device through which individuals who may be reluctant to pay more taxes may do so if they have a great deal of confidence in political institutions.

Our findings also showed that the positive relationships between political trust and support for a tax increase are moderated and weakened by an increased level of perceived tax burden. A high level of perceived tax burden adversely affects the relationship between political trust and support for a tax increase by eroding individuals’ trust in the government and consequently weakening the positive attitudes that individuals with a high level of political trust may exhibit toward support for a tax increase.

Finally, our study has several limitations. First, it was built on one-year cross-sectional data because it included all variables relevant to our model. Therefore, the findings should not be considered causal and, as such, should not be generalized. Second, we relied on the dependent variable, which consisted of one item. Multi-item variables are certainly favored over single-item variables because the former possess more desirable psychometric properties than the latter. Still, studies have shown that single-item variables are not necessarily inferior and that a high correlation between single-item measures and multi-item measures does exist [

49]. Thus, future studies are needed to address the problems noted above and to verify the findings of this study. Last of all, this study was centered on the moderating effects of perceived tax burden, but exploring its mediating effects may also yield insights that enrich our understanding of the dynamic relationships between political trust, taxation, tax burden, and social welfare.