Mediating Effect of Brand Image and Satisfaction on Loyalty through Experiential Marketing: A Case Study of a Sugar Heritage Destination

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Experience

2.2. Brand Image

2.3. Brand Image and Experience

2.4. Experience, Satisfaction, and Loyalty

2.5. Brand Image, Satisfaction, and Loyalty

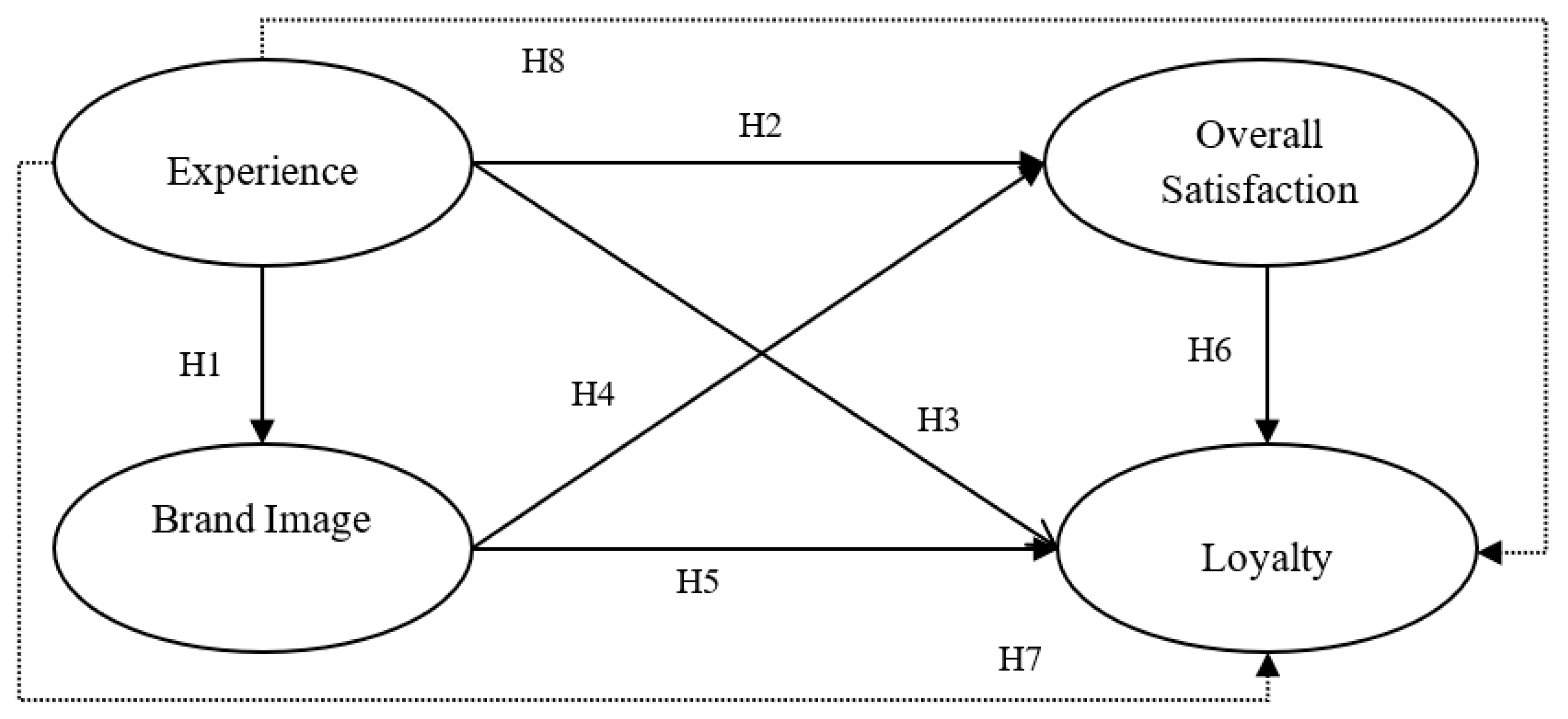

2.6. The Mediating Role of Brand Image and Satisfaction

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Survey Measures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Sample and Responses

4.2. Measurement Model

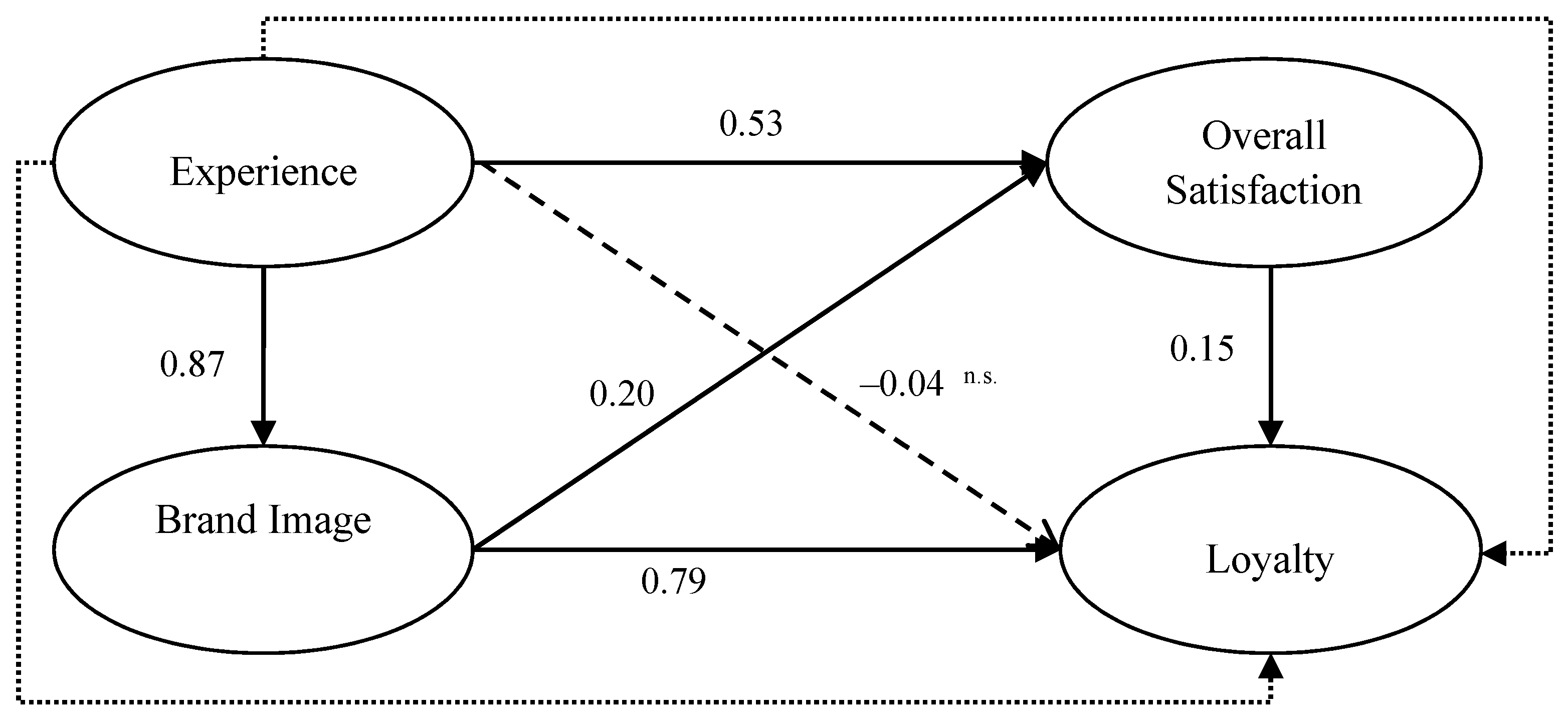

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Managerial Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buckley, R.; Shekari, F.; Mohammadi, Z.; Azizi, F.; Ziaee, M. World heritage tourism triggers urban–rural reverse migration and social change. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W. Braveheart-ed Ned Kelly: Historic films, heritage tourism and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, R.G.; Oh, C.-O.; Jodice, L.W.; Norman, W.C. The role of heritage and cultural elements in coastal tourism destination preferences: A choice modeling-based analysis. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.H.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Grimstad, S. Operating small tourism firms in rural destinations: A social representations approach to examining how small tourism firms cope with non-tourism induced changes. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christou, E. Heritage and cultural tourism: A marketing-focused approach. In International Cultural Tourism: Management, Implications and Cases; Sigala, M., Leslie, D., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.; Llurdes, J. Mines and quarries: Industrial heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale, P. From Tourist Attractions to Heritage Tourism; ELM Publications: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nuryanti, W. Heritage and postmodern tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F. Developing industrial heritage tourism: A case study of the proposed jeep museum in Toledo, Ohio. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.; Witt, S.; Hamer, C. Tourism as experience—The case of heritage parks. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Creating memorable experiences in a reuse heritage site. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Contemporary tourism heritage as heritage tourism: Evidence from Las Vegas and Gold Coast. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Lane, B.; Weston, R.; Davies, N.; Kastenholz, E.; Lima, J.; Majewsjki, J. Industrial Heritage and Agri/Rural Tourism in Europe: A Review of Their Development, Socio-Economic Systems and Future Policy Issues; European Parliament’s Committee on Transport and Tourism: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Modern History. Available online: http://archives.sinica.edu.tw/wp-content/uploads/e06.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.Y.; Bi, N.; Chen, Y. You exist in my song! How a destination-related popular song enhances destination image and visit intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Q. Examining structural relationships among night tourism experience, lovemarks, brand satisfaction, and brand loyalty on “Cultural Heritage Night” in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Clemes, M.D.; Wibisono, N. How experiences with cultural attractions affect destination image and destination loyalty. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2018, 18, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareiro, L.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Remoaldo, P.C. What influences a tourist to return to a cultural destination? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Wong, S.F.; Chang, Y.; Park, J.H. Determinants of customer loyalty in the Korean smartphone market: Moderating effects of usage characteristics. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Reisinger, Y. What are the triggers of Asian visitor satisfaction and loyalty in the Korean heritage site? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrianea, A.; Kamenidou, I.E. Memorable tourism experiences, destination image, satisfaction, and loyalty: An empirical study of Santorini Island. EuroMed J. Bus. 2022, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondoh, S.L., Jr.; Omar, M.W.; Wahid, N.A.; Ismail, I.; Harun, A. The effect of brand image on overall satisfaction and loyalty intention in the context of color cosmetic. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 12, 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, R.V.; Alwi, S.F. Online corporate brand image, satisfaction and loyalty. J. Brand. Manag. 2008, 16, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faullant, R.; Matzler, K.; Fuller, J. The impact of satisfaction and image on loyalty: The case of Alpine ski resorts. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2008, 18, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Cultivating service brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P. Destination image and loyalty development: The impact of tourists’ food experiences at gastronomic events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaiSuar Communication Monly. Available online: https://www.taisugar.com.tw/Monthly/CPN.aspx?ms=1412&p=13386049&s=13386064 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Balcar, M.J.; Pearce, D.G. Heritage tourism on the west coast of New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Rawding, L. Tourism marketing images of industrial cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBoyle, G. Green tourism and Scottish distilleries. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Masberg, B. Factors critical to the success of implementing vintage trolley operations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 335, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, D.; Confer, J.; Bricker, K. Industrial heritage attractions: Types and tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.A.; Davis, J.A. Industrial heritage tourism at the Bingham Canyon Copper Mine. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. The decline of the traditional North Atlantic fisheries and tourism’s response: The cases of Iceland and Newfoundland. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn, A.; Lutz, J. Developing the heritage tourism product in multi-ethnic cities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Affirming authenticity—Consuming cultural heritage. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S. Mines-A tourist attraction: Coal mining in industrial South Wales. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretes, M. Touring mines and mining tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. Exploring the sustainability of mining heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billington, R. Federal investment attracts private investment in industrial historic sites. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 18, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W. From diggers to baristas: Tourist shopping villages in the Victorian goldfields. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2006, 13, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Ballesteros, E.; Herna’ndez Ramı’rez, M. Identity and community: Reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in southern Spain. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánches, A.; Plaza-Mejía, M.A.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buultjens, J.; Brereton, D.; Memmott, P.; Reser, J.; Thomson, L.; O’Rourke, T. The mining sector and indigenous tourism development in Weipa, Queensland. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, H.M. Sustainable heritage tourism marketing and Canada’s Rideau Canal world heritage site. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Marques, C.P.; Lima, J. Understanding and managing the rural tourism experience—The case of a historical village in Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D.M.; Nsiah, C. The economic consequences of community support for tourism: A case study of a heritage fish hatchery. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Weng, J.; Yu, L. Market size, scale economies, and tourism market structure: A case of historic water town tourism in China. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xie, P.; Tsai, M. Perceptions of attractiveness for salt heritage tourism: A tourist perspective. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F. A life cycle model of industrial heritage development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C. The willingness of heritage tourists to pay for perceived authenticity in Pingxi, Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1044–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C.; Saren, M.; Pressey, A. Presence and absence in themed heritage. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, Y. Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.H.; Tzeng, G.H. Exploring heritage tourism performance improvement for making sustainable development strategies using the hybrid-modified MADM model. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 921–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Dong, Y.; Wall, G.; Sun, Y. A value-based analysis of the tourism use of agricultural heritage systems: Duotian Agrosystem, Jiangsu Province, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2136–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Shen, H.J.; Ye, B.H.; Zhou, L. From axe to awe: Assessing the co-effects of awe and authenticity on industrial heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, N.; Fazito, M.; Cunha, A. Tourism development discourse dynamics in a context of conflicts between mining and nature conservation in the Brazilian Cerrado Hotspot. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.T. Heritage place, leisure and tourism. In Heritage, Tourism and Society; Herbert, D.T., Ed.; Mansell: London, UK, 1995; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Falser, M. Industrial Heritage Analysis: World Heritage List and Tentative List; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halewood, C.; Hannam, K. Viking heritage tourism: Authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine II, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. Tourism and hospitality marketing: Fantasy, feeling and fun. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.H. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, Relate to Your Company and Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, M. Brand Sense: Build Powerful Brands through Touch, Taste, Smell, Sight, and Sound; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, J.R. Branding a memorable destination experience: The case of ‘Brand Canada’. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.E.; Wu, C.K. Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J.; Sorensen, F. Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: Testing a scale in the tourism context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. Behavioral science concepts for analyzing the consumer. In Marketing and the Behavioral Sciences; Bliss, P., Ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1963; pp. 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Liljander, V.; Polsa, P.; van Riel, A. Modeling consumer responses to an apparel store brand: Store image as a risk reducer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; Maclnnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orth, U.R.; De Marchi, R. Understanding the relationships between functional, symbolic, and experiential brand beliefs, product experiential attributes, and product schema: Advertising-trial interactions revisited. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D.; Allen, D. Communicating experiences: A narrative approach to creating service brand image. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Oh, H.; Assaf, A.G. A Customer-Based Brand Equity Model for upscale hotels. J. Travel Res. 2011, 51, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Sustainable marketing activities of traditional fashion market and brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.; Abasi, A.; Monfared, A.K. The role of tourist experience in the tourism destination image of Isfahan. J. Tour. Dev. 2018, 7, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.M.; Baumgartner, H. The role of consumption emotions in the satisfaction response. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y. The combined effect of color and music on customer satisfaction in hotel bars. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, L.W.; Milliman, R.E. Atmospheric effects on shopping behavior: A review of the experimental evidence. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Tasci, A.D. Exploring the experiential and sociodemographic drivers of satisfaction and loyalty in the theme park context. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodness, D.; Murray, B. A model of tourist information search behavior. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, O. Understanding and measuring tourist destination images. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.; Makens, J. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Na, W.B.; Marshall, R.; Keller, K.L. Measuring brand power: Validating a model for optimizing brand equity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 1999, 8, 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Whittome, J.R.M.; Brush, G.J. Investigating the service brand: A customer value perspective. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, K.; Taplin, R.H.; Moore, S.A. Using a randomised experiment to test the causal effect of service quality on visitor satisfaction and loyalty in a remote national park. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off-season holiday destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R. The impact of experimental marketing on customer loyalty for fitness clubs: Using brand image and satisfaction as the mediating variables. J. Int. Manag. Stud. 2015, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Back, K.; Barrett, B. Influencing factors on restaurant customers’ revisit intention: The role of emotions and switching barriers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Chew, P. The effects of incentives, deal proneness, satisfaction and tie strength on word-of-mouth behaviour. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2002, 13, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J. Experiential marketing, brand image and brand loyalty: A case study of Starbucks. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T.H. The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainan City Government Visitor to Tourist Spots in Tainan City. Available online: https://admin.twtainan.net/zh-tw/touriststatistics/newsdetail/549 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R. Moderating effects of tourists’ novelty-seeking tendencies on destination image, visitor satisfaction, and short- and long-term revisit intentions. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behavior: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fritz, M.S.; Williams, J.; Lockwood, C.M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, T. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.; Chiu, Y.; Wang, C. The visitor behavioral consequences of experiential marketing: An empirical study on Taipei Zoo. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, T.W.; Lindestad, B. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.J.; Barry, T.E.; Dacin, P.A.; Gunst, R.F. Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; Paddison, B. The direct and indirect influence of experience quality on satisfaction: The importance of emotions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 2779–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenbach, G.; Marell, A. The impact of customer experience on brand equity in a business-to-business services setting. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Chieng, M. Building consumer-brand relationship: A cross-cultural experiential view. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 927–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Study |

|---|---|

| Balcar and Pearce [34] | Differences of site characteristics, development, management and visitor profiles among eight gold/coal mining heritage sites on the West Coast of New Zealand. |

| Bramwell and Rawding [35] | Examine the rationales behind image reshaping in five industrial English cities. |

| Edwards and Llurdes [6] | Examine the potential of industrial heritage, specifically mining areas, transforming into tourist attractions. A typological framework of industrial heritage sites was developed. |

| McBoyle [36] | Adopt a green image strategy in industrial tourism attractions to enhance firms’ environmental reputation by encouraging self-directed improvement in line with environmental accreditation schemes. |

| Harris and Masberg [37] | A cross case analysis on the vintage trolley operations identifying 12 factors to success. |

| Kerstetter, Confer, and Bricker [38] | Examine the relationship between tourists’ visitation types and patterns. |

| Rudd and Davis [39] | Develop industrial heritage tourism to generate a positive image for the copper industry in Utah and to alleviate public fears about pollution and environmental degradation. |

| Prentice et al. [10] | Experiences and benefits segmentation of visitors to a mining-themed industrial heritage park in South Wales UK. |

| Baum [40] | Examine the policy issues for diversifying fishery industry in two island communities: Iceland and Newfoundland. |

| Caffyn and Lutz [41] | The policy issues designed to encourage a community focus in urban industrial heritage tourism. |

| McIntosh and Prentice [42] | The experiential and emotive processes in visitors’ interaction with industrial heritage attraction settings to affirm authenticity. |

| Wanhill [43] | The key issues involved in setting up mines and industrial remains as tourist attractions in South Wales UK. |

| Pretes [44] | Examine tourist–local interactions and the use of tourism as a vehicle for narrating an indigenous discourse at the silver mines in Potosí, Bolivia. |

| Cole [45] | Using economic, social, and environmental perspectives to examine the development of mining heritage tourism towards sustainable objectives. |

| Billington [46] | Discuss how federal investment attracts private investment in the Blackstone Valley, America’s industrial birthplace, and why people are returning. |

| Frost [47] | Examine the relationships between heritage tourism and shopping in two towns (once gold mines): Castlemaine and Maldon, Australia. |

| Xie [9] | Evaluate the proposal for a Jeep Museum in Ohio from six key attributes of developing industrial heritage tourism. |

| Ruiz Ballesteros and Herna’ndez Ramı’rez [48] | The relationship between local community (namely community identity) and the development of mining heritage tourism in southern Spain. |

| Vargas-Sánches, Plaza-Mejía, and Porras-Bueno [49] | The attitudes of local residents towards tourism development in Minas de Riotinto (traditionally involved in mining activity) and the relationship to community satisfaction. |

| Buultjens, Brereton, Memmott, Reser, Thomson, and O’Rourke [50] | Indigenous involvement in tourism in the Weipa region of northwest Queensland and the role of a mining operation called Rio Tinto Aluminium in assisting this development. The facilitator approach adopted is likely to limit the effectiveness of the mine’s efforts. |

| Donohoe [51] | Propose a sustainable marketing model and test it on a World Heritage Site—the Rideau Canal in Canada. |

| Kastenholz, Carneiro, Marques, and Lima [52] | Examine the experience of tourists and residents in a small village in Central Portugal that uses its heritage and traditions to promote rural tourism. |

| Spencer and Nsiah [53] | A case study on the economic consequences of community support for tourism development in a heritage fish hatchery. |

| Ma, Weng, and Yu [54] | A case study on the structural evolution of a historic water town in China, and the role of scale economies and market size on it. |

| Wu, Xie, and Tsai [55] | Examine the key attributes of attractiveness for salt destinations in Taiwan and the preferred experiences and programs. |

| Xie [56] | Propose a life cycle model of industrial heritage development and apply it to the LX Factory in Lisbon, Portugal. |

| Lin [57] | Explore visitors’ perceptions of authenticity and its impact on intrinsic value in Pingxi, Taiwan. |

| Goulding, Saren, and Pressey [58] | Investigate the commercial staging of history in a case of an industrial museum and examine how the past is experienced and understood through a series of factors. |

| Lin and Liu [59] | Explore the construct of authenticity in the context of industrial heritage in Taiwan and examine its relationship with motivation and loyalty. |

| Peng and Tzeng [60] | Propose a hybrid-modified MADM model to develop performance-improving strategies for industrial heritage tourism. |

| Su, Dong, Wall, and Sun [61] | Conceptualize a multiple value system of agricultural heritage in China to explore the approach of integrating the heritage values with tourism. |

| Yan, Shen, Ye, and Zhou [62] | Assess the effects of awe experience, authenticity experience, and perceived value on visitors’ behavioral intentions towards the industrial heritage park in east China. |

| Marques, Fazito, and Cunha [63] | Explores the conflicts between tourism development and mining, and concludes that more balanced human development should be ensured in public planning processes. |

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Monthly income (NT) households | ||||

| Male | 211 | 42.3 | <30,000 | 164 | 32.9 |

| Female | 288 | 57.7 | 30,000~49,999 | 198 | 39.7 |

| Age | 50,000~69,999 | 88 | 17.6 | ||

| 18–25 | 75 | 15.0 | >70,000 | 49 | 9.8 |

| 26–35 | 155 | 31.1 | Residence | ||

| 36–45 | 132 | 26.5 | Tainan City | 85 | 17.0 |

| 46–55 | 90 | 18.0 | Northern area | 175 | 35.1 |

| 56 and older | 53 | 10.6 | Central area | 85 | 17.0 |

| Education | Southern area | 154 | 30.9 | ||

| Secondary school or below | 33 | 6.6 | Travel style | ||

| High/vocational school | 125 | 25.1 | Individual travel | 141 | 28.3 |

| University/college | 300 | 60.1 | Group travel | 358 | 71.7 |

| Graduate school or above | 41 | 8.2 | Sources | ||

| Occupation | TV | 50 | 8.5 | ||

| Government/education agencies | 32 | 6.4 | Newspapers | 30 | 5.1 |

| Manufacturing industry | 15 | 3.0 | Websites | 82 | 13.9 |

| Service industry | 338 | 67.7 | Brochures/DM | 40 | 6.8 |

| Technician | 30 | 6.0 | Families/friends | 108 | 18.3 |

| Unemployed (students, retired) | 84 | 16.8 | Travel agencies | 281 | 47.6 |

| Constructs and Items | Mean | Factor Loadings | t-Value | SMC | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | ||||||

| Sense | 0.74 | 0.49 | ||||

| The landscaping in this village attracts my visual attention | 3.61 | 0.668 | NA | 0.446 | ||

| The trip in this village is interesting | 3.86 | 0.652 | 12.486 | 0.425 | ||

| This village is full of sensory appeal | 4.03 | 0.772 | 14.099 | 0.596 | ||

| Feel | 0.78 | 0.54 | ||||

| This village puts me in a nostalgic mood | 3.77 | 0.68 | NA | 0.462 | ||

| This village induces feelings and sentiment | 4.18 | 0.747 | 14.394 | 0.559 | ||

| This village makes me respond in an emotional manner | 4.13 | 0.779 | 14.785 | 0.606 | ||

| Think | 0.85 | 0.58 | ||||

| This village makes me think | 4.12 | 0.723 | 17.424 | 0.523 | ||

| This village appeals to my creative thinking | 3.89 | 0.715 | 17.168 | 0.511 | ||

| I engage in a lot of thinking in this village | 4.04 | 0.793 | 20 | 0.629 | ||

| This village stimulates my curiosity | 3.97 | 0.815 | NA | 0.663 | ||

| Act | 0.86 | 0.60 | ||||

| I would like to take pictures in this village as mementos | 4.09 | 0.728 | NA | 0.531 | ||

| I would like to share experiences in this village | 4.06 | 0.847 | 18.571 | 0.717 | ||

| I would like to engage in physical activities | 4.04 | 0.831 | 17.789 | 0.691 | ||

| I would like to search related information | 3.87 | 0.688 | 14.606 | 0.474 | ||

| Relate | 0.85 | 0.59 | ||||

| This village induces in me a sense of identity towards ecological conservation | 3.89 | 0.745 | 17.066 | 0.555 | ||

| This village reminds me of social arrangements | 3.89 | 0.818 | 19.104 | 0.669 | ||

| This village makes me think about relationships | 3.94 | 0.726 | 16.635 | 0.526 | ||

| I can relate to other people through visiting this village | 3.75 | 0.79 | NA | 0.624 | ||

| Brand Image | ||||||

| Functional | 0.85 | 0.65 | ||||

| This village provides both educational and entertaining activities | 4.30 | 0.753 | NA | 0.567 | ||

| This village allows for stress relief | 4.19 | 0.832 | 18.341 | 0.693 | ||

| This village provides healthy leisure activities | 4.18 | 0.838 | 18.467 | 0.703 | ||

| Experiential | 0.86 | 0.61 | ||||

| This village is a place with a variety of attractions | 4.17 | 0.794 | NA | 0.631 | ||

| This village is pleasant | 4.18 | 0.795 | 19.322 | 0.632 | ||

| This village is full of fun | 3.90 | 0.762 | 18.314 | 0.581 | ||

| The activities in this village impressed me a lot | 4.09 | 0.76 | 18.247 | 0.577 | ||

| Symbolic | 0.84 | 0.56 | ||||

| This village is full of arts/humanity atmosphere | 4.06 | 0.811 | NA | 0.657 | ||

| This village has abundant drum-related culture | 4.30 | 0.75 | 17.998 | 0.562 | ||

| This village is rich in ecology | 3.90 | 0.757 | 18.234 | 0.574 | ||

| This village has cordial interpreters with expertise | 4.21 | 0.673 | 15.743 | 0.453 |

| Construct | χ2 | p | CFI | NNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | 349.03 | 0.000 | 0.956 | 0.946 | 0.06 |

| Brand image | 146.11 | 0.000 | 0.968 | 0.956 | 0.072 |

| Overall measurement model | 119.56 | 0.000 | 0.985 | 0.98 | 0.054 |

| Constructors and Items | Factor Loadings | t-Value | Squared Multiple Correlation | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | 0.91 | 0.67 | |||

| Sense | 0.781 | NA | 0.61 | ||

| Feel | 0.806 | 19.636 | 0.649 | ||

| Think | 0.884 | 22.103 | 0.782 | ||

| Act | 0.843 | 20.812 | 0.711 | ||

| Relate | 0.78 | 18.861 | 0.609 | ||

| Brand Image | 0.89 | 0.73 | |||

| Functional | 0.774 | NA | 0.599 | ||

| Experiential | 0.863 | 21.171 | 0.745 | ||

| Symbolic | 0.921 | 22.863 | 0.848 | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.80 | 0.80 | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.894 | NA | 0.80 | ||

| Loyalty | 0.90 | 0.74 | |||

| Revisit | 0.857 | NA | 0.734 | ||

| Recommend | 0.847 | 23.656 | 0.717 | ||

| Share | 0.878 | 25.018 | 0.771 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience | 0.82 | |||

| 2. Brand Image | 0.78 | 0.85 | ||

| 3. Satisfaction | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.89 | |

| 4. Loyalty | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.86 |

| Hypothesized Path | β | t Value | R2 | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Experience → Brand Image | 0.87 | 16.43 *** | 0.75 | Supported |

| H2. Experience → Overall Satisfaction | 0.53 | 5.09 *** | Supported | |

| H3: Experience → Loyalty | −0.044 | −0.508 | Not Supported | |

| H4: Brand Image → Overall Satisfaction | 0.20 | 1.98 * | 0.51 | Supported |

| H5: Brand Image → Loyalty | 0.79 | 9.03 *** | 0.74 | Supported |

| H6: Overall Satisfaction → Loyalty | 0.15 | 2.74 ** | Supported | |

| H7: Experience → Brand Image → Loyalty | NA | Supported | ||

| H8: Experience → Overall Satisfaction → Loyalty | NA | Supported |

| Variables | Point Estimate | Bootstrapping | MacKinnon PRODCLIN2 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| Total Effects | |||||||

| EXP → LOY | 1.027 | 0.906 | 1.161 | 0.905 | 1.161 | ||

| Total Indirect Effects | |||||||

| EXP → LOY | 1.088 | 0.824 | 1.381 | 0.822 | 1.374 | 0.67 | 1.27 |

| Specific Indirect Effects | |||||||

| EXP → BI → LOY | 0.946 | 0.67 | 1.26 | ||||

| EXP → SAT → LOY | 0.107 | 0.02 | 0.24 | ||||

| EXP → BI → SAT → LOY | 0.036 | 0.01 | 1.06 | ||||

| Total Direct Effects | |||||||

| EXP → LOY | −0.06 | −0.335 | 0.203 | −0.334 | 0.204 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, A.H.; Wu, R.Y. Mediating Effect of Brand Image and Satisfaction on Loyalty through Experiential Marketing: A Case Study of a Sugar Heritage Destination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127122

Chen AH, Wu RY. Mediating Effect of Brand Image and Satisfaction on Loyalty through Experiential Marketing: A Case Study of a Sugar Heritage Destination. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127122

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Aileen H., and Ryan Y. Wu. 2022. "Mediating Effect of Brand Image and Satisfaction on Loyalty through Experiential Marketing: A Case Study of a Sugar Heritage Destination" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127122

APA StyleChen, A. H., & Wu, R. Y. (2022). Mediating Effect of Brand Image and Satisfaction on Loyalty through Experiential Marketing: A Case Study of a Sugar Heritage Destination. Sustainability, 14(12), 7122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127122