Out of Sight, Out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review and Conceptual Model

1.2. Smart Working, Job Demands/Resources and Exhaustion: The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Self-Report Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.3. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messenger, J.; Llave, O.V.; Gschwind, L.; Boehmer, S.; Vermeylen, G.; Wilkens, M. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Cameron, L.; Garrett, L. Alternative Work Arrangements: Two Images of the New World of Work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, T.D. The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.; Capone, V. Smart Working and Well-Being before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1516–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, R.; Parisi, T.; Tira, L. Gli Smart Workers Tra Solitudine e Collaborazione. Cambio 2019, 9, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 7th ed.; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: Where We Were, Where We Head to; Joint Research Centre of the European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Corso, M. Il Ruolo e Le Prospettive Dello Smart Working Nella PA Oltre La Pandemia. 2021. Available online: https://sna.gov.it/fileadmin/files/workshop_seminari/0_2021/Conferenza_Ripensare_la_PA/M._Corso_Ruolo_e_prospettive_smart_working_nella_PA.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Rivoluzione Smart Working: Un Futuro Da Costruire Adesso; Osservatorio Smart Working: Milano, Italy, 2021.

- Albano, R.; Curzi, Y.; Parisi, T.; Tirabeni, L. Perceived autonomy and discretion of mobile workers. Studi Organ. 2018, 2, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, G.; Taskin, L. Out of Sight, Out of Mind in a New World of Work? Autonomy, Control, and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathini, D.R.; Kandathil, G.M. Bother me only if the client complains: Control and resistance in home-based telework in India. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, M.; Sretenović, S.; Bugarčić, M. Remote Working for Sustainability of Organization during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediator-Moderator Role of Social Support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, B.; Ladipo, D.; Wilkinson, F. The Prevalence and Redistribution of Job Insecurity and Work Intensification. In Job Insecurity and Work Intensification; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Green, F. It’s Been A Hard Day’s Night: The Concentration and Intensification of Work in Late Twentieth-Century Britain. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2001, 39, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R. Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Erickson, J.J.; Holmes, E.K.; Ferris, M. Workplace flexibility, work hours, and work-life conflict: Finding an extra day or two. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, K.L.U.S. Empowerment or enslavement: The impact of technology-driven work intrusions on work–life balance. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 38, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Weale, V.; Lambert, K.A.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Oakman, J. Working at Home: The Impacts of COVID-19 on Health, Family-Work-Life Conflict, Gender, and Parental Responsibilities. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Seo, H.; Forbes, S.; Birkett, H. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Changing Preferences and the Future of Work; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca, D.; Oggero, N.; Profeta, P.; Rossi, M. Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2020, 18, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.D.; Kurland, N.B. Telecommuting, professional isolation, and employee development in public and private organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Dino, R.N. The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errichiello, L.; Pianese, T. Toward a theory on workplaces for smart workers. Facilities 2019, 38, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. ISBN 978-94-007-5640-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestel, S.; Schmidt, K.-H. Direct and interaction effects among the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: Results from two German longitudinal samples. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.; Kanneganti, A.; Lim, L.J.; Tan, M.; Chua, Y.X.; Tan, L.; Sia, C.H.; Denning, M.; Goh, E.T.; Purkayastha, S.; et al. Burnout and Associated Factors Among Health Care Workers in Singapore During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Popescu, G.H. Psychological Distress, Moral Trauma, and Burnout Syndrome among COVID-19 Frontline Medical Personnel. Psychosoc. Issues Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 9, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Girardi, D.; Dal Corso, L.; Yıldırım, M.; Converso, D. The perceived risk of being infected at work: An application of the job demands–resources model to workplace safety during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressley, T. Factors Contributing to Teacher Burnout During COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T.; Lam, M.K.; Reddy, P.; Wong, P. Factors Associated with Work-Related Burnout among Corporate Employees Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.E.; Mazzola, J.J.; Bauer, J.J.; Krueger, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work Stress 2011, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Alarcon, G.M.; Bragg, C.B.; Hartman, M.J. A meta-analytic examination of the potential correlates and consequences of workload. Work Stress 2015, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; Le Pine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, J.J.; Pierro, A.; Barbieri, B.; De Carlo, N.A.; Falco, A.; Kruglanski, A.W. One size doesn’t fit all: The influence of supervisors’ power tactics and subordinates’ need for cognitive closure on burnout and stress. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A.J. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.A.; Webster, S.; Van Laar, D.; Easton, S. Psychometric analysis of the UK Health and Safety Executive’s Management Standards work-related stress Indicator Tool. Work Stress 2008, 22, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.L.; Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S.K. Theories of job stress and the role of traditional values: A longitudinal study in China. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Demerouti, E. How does chronic burnout affect dealing with weekly job demands? A test of central propositions in JD-R and COR-theories. Appl. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, A.E.S.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2006, 32, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Eissenstat, S.J. A longitudinal examination of the causes and effects of burnout based on the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2018, 18, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social support at work: An integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yürür, S.; Sarikaya, M. The Effects of Workload, Role Ambiguity, and Social Support on Burnout Among Social Workers in Turkey. Adm. Soc. Work 2012, 36, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B. The Gain Spiral of Resources and Work Engagement: Sustaining a Positive Worklife. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 118–131. ISBN 978-1-84169-736-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Heuven, E.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Working in the Sky: A Diary Study on Work Engagement among Flight Attendants. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, K.; Cieslak, R.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Rogala, A.; Benight, C.C.; Luszczynska, A. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.M.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Schoch, S.; Scholz, U.; Rackow, P.; Schüler, J.; Wegner, M.; Keller, R. Teachers’ perceived time pressure, emotional exhaustion and the role of social support from the school principal. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, M.J.A.; García-Ramírez, M. Social support and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2005, 19, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, M. Telework amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on work style reform in Japan. Corp. Gov. 2021, 21, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaus, K.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R.; Chan, K.; Huang, A. Benefits and stressors—Perceived effects of ICT use on employee health and work stress: An exploratory study from Austria and Hong Kong. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2015, 10, 28838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Duck, J.; Jimmieson, N. E-mail in the workplace: The role of stress appraisals and normative response pressure in the relationship between e-mail stressors and employee strain. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2014, 21, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. An affordance perspective of team collaboration and enforced working from home during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing Costs of Technology Use during COVID-19 Remote Working: An Investigation Using the Italian Translation of the Technostress Creators Scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Esposito, A.; Sciarra, I.; Chiappetta, M. Definition, symptoms and risk of techno-stress: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kee, K.; Mao, C. Multitasking and Work-Life Balance: Explicating Multitasking When Working from Home. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2021, 65, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Flamini, G.; Gnan, L.; Pellegrini, M.M. Looking for meanings at work: Unraveling the implications of smart working on organizational meaningfulness. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.M.; Hislop, D.; Cartwright, S. Social support in the workplace between teleworkers, office-based colleagues and supervisors. New Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.; Teo, S.; McLeod, L.; Tan, F.B.; Bosua, R.; Gloet, M. The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innstrand, S.T.; Langballe, E.M.; Falkum, E.; Aasland, O.G. Exploring within- and between-gender differences in burnout: 8 different occupational groups. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2011, 84, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, K.; Honkonen, T.; Virtanen, M.; Aromaa, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Burnout in Relation to Age in the Adult Working Population. J. Occup. Health 2008, 50, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S.; Belios, E. Effect of Age on Job Satisfaction and Emotional Exhaustion of Primary School Teachers in Greece. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, E.W.; Shapard, L. Employee Burnout: A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Age or Years of Experience. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2004, 3, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Blanc, M.-E.; Beauregard, N. Do age and gender contribute to workers’ burnout symptoms? Occup. Med. 2018, 68, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sillero, A.; Zabalegui, A. Organizational Factors and Burnout of Perioperative Nurses. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S.; De Cuyper, N.; Kinnunen, U.; Ruokolainen, M.; Rantanen, J.; Mäkikangas, A. The prospective effects of work–family conflict and enrichment on job exhaustion and turnover intentions: Comparing long-term temporary vs. permanent workers across three waves. Work Stress 2015, 29, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, A.F.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Houtman, I.L.D.; van den Bossche, S.; Smulders, P.; Taris, T.W. Can labour contract differences in health and work-related attitudes be explained by quality of working life and job insecurity? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2012, 85, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimaki, M.; Joensuu, M.; Virtanen, P.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J. Temporary employment and health: A review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchi, M.; Emanuel, F.; Chambel, M.J.; Ghislieri, C. Job insecurity, workload and job exhaustion in temporary agency workers (TAWs): Gender Differences. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. (Eds.) Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, N.A.; Falco, A.; Capozza, D. Test di Valutazione del Rischio Stress Lavoro-Correlato Nella Prospettiva del Benessere Organizzativo, Qu-Bo [Test for the Assessment of Work-Related Stress Risk in the Organizational Well-Being Perspective, Qu-Bo]; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Converso, D.; Bruno, A.; Capone, V.; Colombo, L.; Falco, A.; Galanti, T.; Girardi, D.; Guidetti, G.; Viotti, S.; Loera, B. Working during a Pandemic between the Risk of Being Infected and/or the Risks Related to Social Distancing: First Validation of the SAPH@W Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, J.T. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling: A Comprehensive Introduction; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-87131-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. SemTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/semTools/index.html (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Nonnormal and Categorical Data in Structural Equation Modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed.; Quantitative methods in education and the behavioral sciences: Issues, research, and teaching; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 439–492. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, T.E.; Atinc, G.; Breaugh, J.A.; Carlson, K.D.; Edwards, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Gajendran, R.S. Unpacking the Role of a Telecommuter’s Job in Their Performance: Examining Job Complexity, Problem Solving, Interdependence, and Social Support. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Neal, M.B.; Newsom, J.T.; Brockwood, K.J.; Colton, C.L. A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Dual-Earner Couples’ Utilization of Family-Friendly Workplace Supports on Work and Family Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felstead, A.; Henseke, G. Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work-life balance. New Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, E.; Bentley, T.; Shafaei, A.; Farr-Wharton, B.; Onnis, L.-A.; Omari, M. Forced flexibility and remote working: Opportunities and challenges in the new normal. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lau, J.T.; Lau, M.M. Development and validation of the conservation of resources scale for COVID-19 in the Chinese adult general population. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moglia, M.; Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Telework, Hybrid Work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: Towards Policy Coherence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasharudin, N.A.M.; Idris, M.A.; Loh, M.Y.; Tuckey, M. The role of psychological detachment in burnout and depression: A longitudinal study of Malaysian workers. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormann, C.; Griffin, M.A. Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, S.; Armon, G.; Shirom, A.; Shapira, I. Exploring the reciprocal causal relationship between job strain and burnout: A longitudinal study of apparently healthy employed persons. Stress Health 2011, 27, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, L.L.; Soria, M.S.; Martinez, I.M.M.; Schaufeli, W. Extension of the Job Demands-Resources model in the prediction of burnout and engagement among teachers over time. Psicothema 2008, 20, 354–360. [Google Scholar]

- Davoli, M.; de’ Donato, F.; De Sario, M.; Di Blasi, C.; Michelozzi, P.; Noccioli, F.; Orrù, D.; Rossi, P. Andamento Della Mortalità Giornaliera (SiSMG) Nelle Città Italiane in Relazione All’epidemia Di COVID-19. Rapporto 1 Settembre 2020–29 Giugno 2021; Ministero della Salute: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Di Sipio, A. When Does Work Interfere with Teachers’ Private Life? An Application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Girardi, D.; De Carlo, A.; Comar, M. The moderating role of job resources in the relationship between job demands and interleukin-6 in an Italian healthcare organization. Res. Nurs. Health 2018, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falco, A.; Girardi, D.; Parmiani, G.; Bortolato, S.; Piccirelli, A.; Bartolucci, G.B.; De Carlo, N.A. Presenteismo e Salute Dei Lavoratori: Effetti Di Mediazione Sullo Strain Psico-Fisico in Un’indagine Longitudinale [Presenteeism and Workers’ Health: Effects of Mediation on Psycho-Physical Stress in a Longitudinal Study]. G Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2013, 35, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wendsche, J.; Ihle, A.; Wegge, J.; Penz, M.S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Kliegel, M. Prospective associations between burnout symptomatology and hair cortisol. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, A.; Bohle, P.; Iskra-Golec, I.; Jansen, N.; Jay, S.; Rotenberg, L. Working Time Society consensus statements: Evidence-based effects of shift work and non-standard working hours on workers, family and community. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pijpker, R.; Kerksieck, P.; Tušl, M.; de Bloom, J.; Brauchli, R.; Bauer, G.F. The Role of Off-Job Crafting in Burnout Prevention during COVID-19 Crisis: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenkranius, M.K.; Rink, F.A.; De Bloom, J.; van den Heuvel, M. The design and development of a hybrid off-job crafting intervention to enhance needs satisfaction, well-being and performance: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Workload, Techno Overload, and Behavioral Stress during COVID-19 Emergency: The Role of Job Crafting in Remote Workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zürcher, A.; Galliker, S.; Jacobshagen, N.; Mathieu, P.L.; Eller, A.; Elfering, A. Increased Working from Home in Vocational Counseling Psychologists During COVID-19: Associated Change in Productivity and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Allan, B.; Clark, M.; Hertel, G.; Hirschi, A.; Kunze, F.; Shockley, K.; Schoss, M.; Sonnentag, S.; Zacher, H. Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2021, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exhaustion (T2) | 2.59 | 1.12 | — | |||

| 2. Exhaustion (T1) | 2.54 | 1.15 | 0.61 *** | — | ||

| 3. Workload (T1) | 3.94 | 1.17 | 0.23 ** | 0.35 *** | — | |

| 4. Social support (T1) | 7.13 | 2.05 | −0.39 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.13 † | — |

| Predictors (T1) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.51 *** | 0.09 | 2.50 *** | 0.09 | 2.52 *** | 0.12 | 2.51 *** | 0.12 |

| Gender 1 | −0.16 | 0.13 | −0.15 | 0.13 | ||||

| Age | 0.01 * | 0.01 | 0.01 * | 0.01 | ||||

| Type of contract 2 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.15 | ||||

| Exhaustion | 0.52 *** | 0.07 | 0.50 *** | 0.07 | 0.53 *** | 0.07 | 0.52 *** | 0.07 |

| Workload | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Social support | −0.09 * | 0.04 | −0.15 *** | 0.04 | −0.08 * | 0.04 | −0.14 ** | 0.04 |

| Work arrangement 3 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Workload x work arrangement | 0.21 † | 0.11 | 0.22 † | 0.11 | ||||

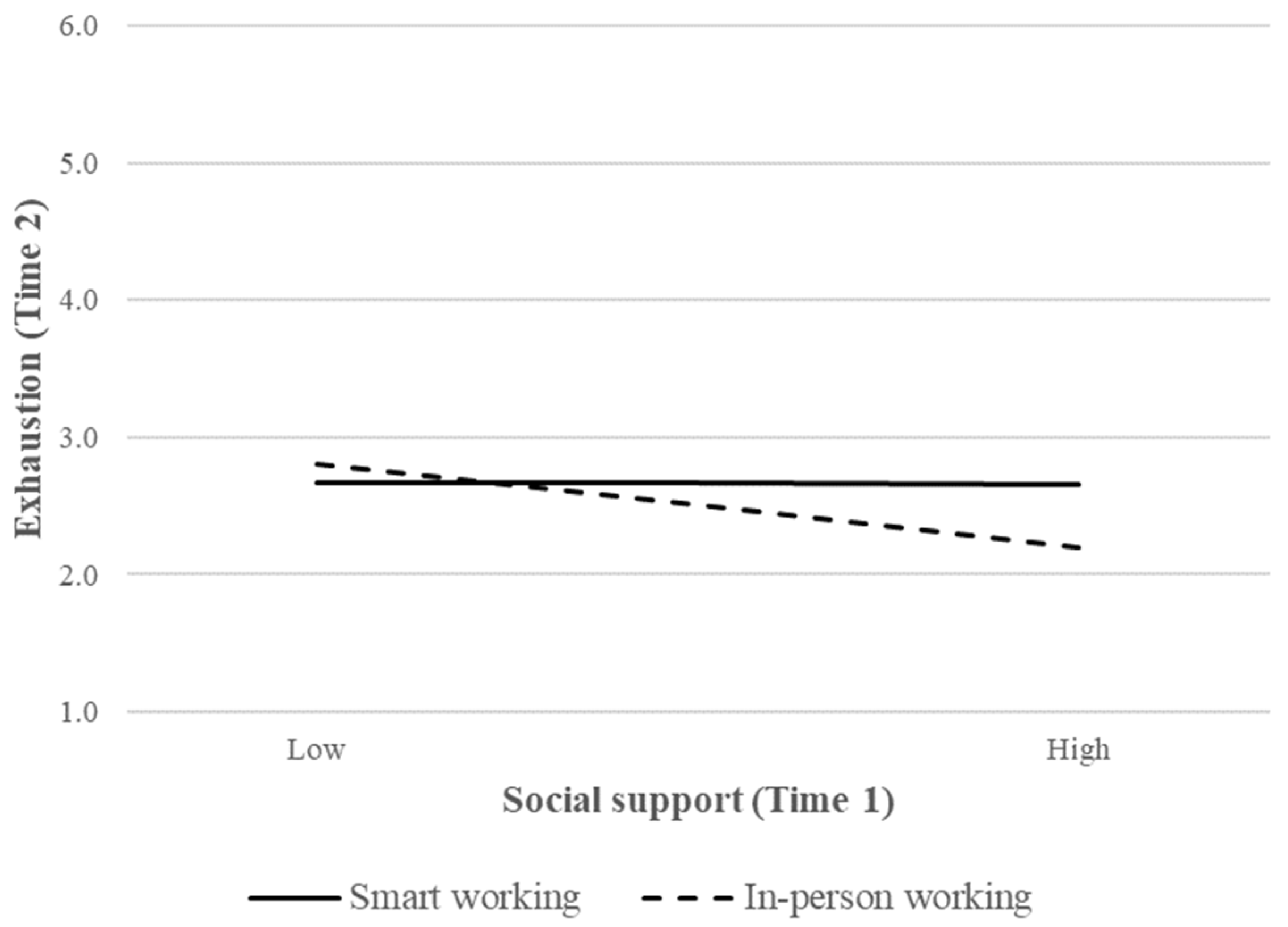

| Social support x work arrangement | 0.15 * | 0.07 | 0.14 * | 0.06 | ||||

| Total R2 | 0.40 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.44 *** | ||||

| Change in R2 | 0.02 * | 0.02 * | ||||||

| Simple slope workload (in-person) | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.07 | ||||

| Simple slope workload (smart working) | 0.15 † | 0.09 | 0.16 † | 0.09 | ||||

| Simple slope social support (in-person) | −0.15 *** | 0.04 | −0.14 ** | 0.04 | ||||

| Simple slope social support (smart working) | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Dal Corso, L.; Arcucci, E.; Falco, A. Out of Sight, Out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7121. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127121

De Carlo A, Girardi D, Dal Corso L, Arcucci E, Falco A. Out of Sight, Out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7121. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127121

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Carlo, Alessandro, Damiano Girardi, Laura Dal Corso, Elvira Arcucci, and Alessandra Falco. 2022. "Out of Sight, Out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7121. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127121

APA StyleDe Carlo, A., Girardi, D., Dal Corso, L., Arcucci, E., & Falco, A. (2022). Out of Sight, Out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(12), 7121. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127121