Ethical Leadership, Bricolage, and Eco-Innovation in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective

Abstract

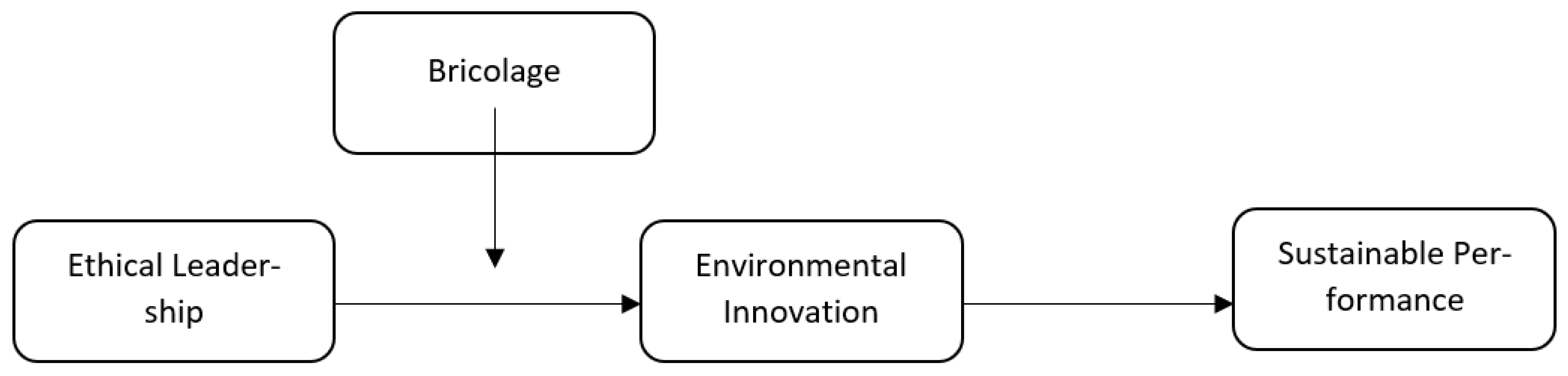

:1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Ethical Leadership and Environmental Innovation

2.2. Environmental Innovation and Sustainable Performance

2.3. Environmental Innovation as Mediator

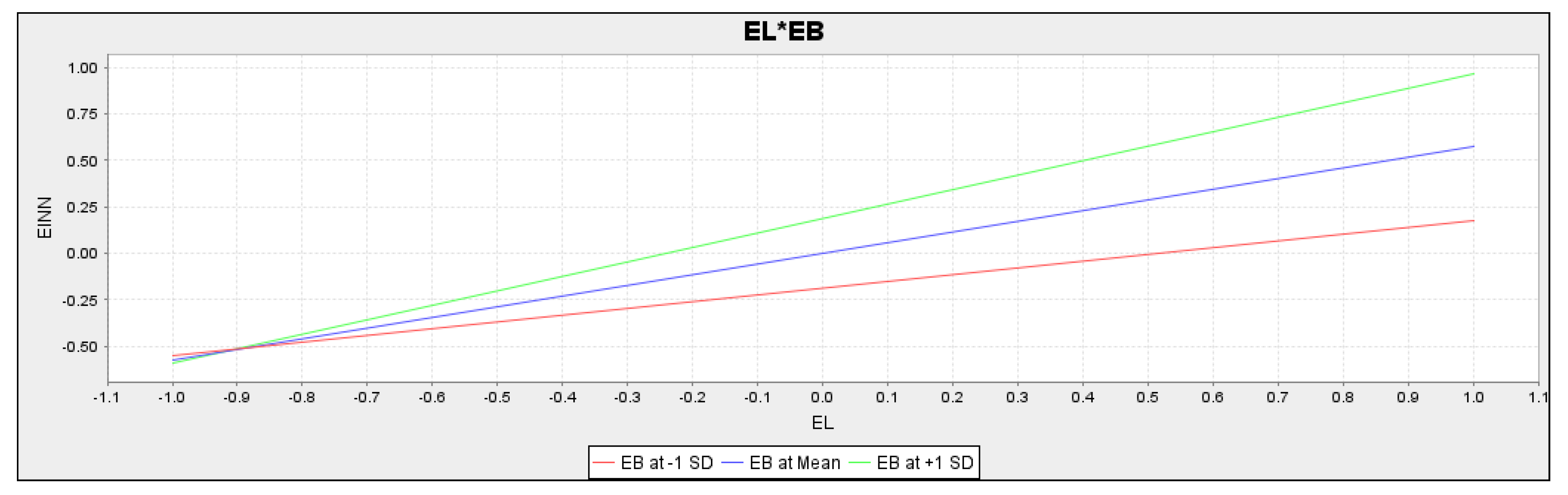

2.4. Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Bricolage

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Context of Study, Population, and Sample Size

3.2. Demographics Analysis

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Screening

3.5. Descriptive Analysis

3.6. Measurement Model Analysis

3.7. Structural Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Direction of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Westerman, J.W.; Nafees, L.; Westerman, J. Cultivating Support for the Sustainable Development Goals, Green Strategy and Human Resource Management Practices in Future Business Leaders: The Role of Individual Differences and Academic Training. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastini, R.; Kallis, G.; Hickel, J. A Green New Deal without growth? Ecol. Econ. 2021, 179, 106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Sustainable leadership in higher education institutions: Social innovation as a mechanism. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 2021, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Luthra, S.; Jakhar, S.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Rai, D.P. A framework to overcome sustainable supply chain challenges through solution measures of industry 4.0 and circular economy: An automotive case. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Liu, L.; Tan, J. Creative leadership, innovation climate and innovation behaviour: The moderating role of knowledge sharing in management. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, Y. Sustainable Leadership in Frontier Asia Region: Managerial Discretion and Environmental Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.T.; Zhuang, M.E.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Yang, J.J. Research on sustainable development and efficiency of China’s E-Agriculture based on a data envelopment analysis-Malmquist model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable development: The colors of sustainable leadership in learning organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-SulejKnudsen, K. Sustainable leadership, justice climate and organizational citizenship behavior towards environment. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management Seattle: Washington, WA, USA, 2022; p. 98101. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Busser, J.; Liu, A. Authentic leadership and career satisfaction: The meditating role of thriving and conditional effect of psychological contract fulfillment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2117–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapta, I.; Sudja, I.N.; Landra, I.N.; Rustiarini, N.W. Sustainability performance of organization: Mediating role of knowledge management. Economies 2021, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Akhtar, M.W.; Hussain, K.; Junaid, M.; Syed, F. “Being true to oneself”: The interplay of responsible leadership and authenticity on multi-level outcomes. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 408–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Mitchell, M.S. Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2010, 20, 583–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, G.; Karau, S.J.; Dai, Y.; Lee, S. A three-level examination of the cascading effects of ethical leadership on employee outcomes: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Wang, D.; Hannah, S.T.; Balthazard, P.A. A neurological and ideological perspective of ethical leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarestky, J.; Collins, J.C. Supporting the United Nations’ 2030 sustainable development goals: A call for international HRD action. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2017, 20, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Liu, M. Managerial competencies and development in the digital age. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2021, 10, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. Ethical leadership and sustainable performance of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. J. Glob. Bus. Technol. 2020, 16, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Nasim, A.; Khan, S.A.R.R. A moderated-mediation analysis of psychological empowerment: Sustainable leadership and sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulasmi, E.; Agussani Tanjung, H. Bridging the Way Towards Sustainability Performance Through Safety, Empowerment and Learning: Using Sustainable Leadership as Driving Force. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 10, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiar, A.; Wang, Y. Managers’ leadership, compensation and benefits, and departments’ performance: Evidence from upscale hotels in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawat, P. The relationships among transformational leadership, sustainable leadership, lean manufacturing and sustainability performance in Thai SMEs manufacturing industry. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 1014–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Halim, H.A. How does sustainable leadership influence sustainable performance? Empirical evidence from selected ASEAN countries. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020969394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F. Ethical leadership in sustainable organizations: The moderating role of general self-efficacy and the mediating role of organizational trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 22, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Walsh, G.; Lerner, D.; Fitza, M.A.; Li, Q. Green innovation, managerial concern and firm performance: An empirical study. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, C.; Chung, Y.; Chun, D.; Han, S.; Lee, D. Impact of green innovation on labor productivity and its determinants: An analysis of the Korean manufacturing industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przychodzen, W.; Leyva-de la Hiz, D.I.; Przychodzen, J. First-mover advantages in green innovation—Opportunities and threats for financial performance: A longitudinal analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, F. Environmental innovation for sustainable development: The role of China. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.N.H.; Halim, H.A.H.A. Insights on entrepreneurial bricolage and frugal innovation for sustainable performance. Bus. Strateg. Dev. 2021, 4, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizarci-Payne, A.K.; İpek, İ.; Kurt Gümüş, G. How environmental innovation influences firm performance: A meta-analytic review. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 1174–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A.; Kemp, R. Measuring Eco-Innovation [Internet]; Unu-Merit: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2009; Available online: http://www.merit.unu.edu (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Long, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Oh, K.; Han, I.; Yan, J. The effect of environmental innovation behavior on economic and environmental performance of 182 Chinese firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Kotsemir, M.; Vinci, C.P. The role of environmental innovation through the technological proximity in the implementation of the sustainable development. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q. The era of environmental sustainability: Ensuring that sustainability stands on human resource management. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeltzu-Jaka, E.; Erauskin-Tolosa, A.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. Shedding light on the determinants of eco-innovation: A meta-analytic study. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Laakso, S.; Lonkila, A.; Kaljonen, M. Moving beyond disruptive innovation: A review of disruption in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Baker, T.; Senyard, J.M. A measure of entrepreneurial bricolage behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, S. The creative industries: An entrepreneurial bricolage perspective. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senyard, J.M.; Baker, T.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a path to innovation for resource constrained new firms. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 10510, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Zhao, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. How Bricolage Drives Corporate Entrepreneurship: The Roles of Opportunity Identification and Learning Orientation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W. Innovating with Limited Resources: The Antecedents and Consequences of Frugal Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akhtar, S.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, P.N.; Tian, H.; Naz, S.; Dâmaso, M.; Santos, R.S. Assessing the Relationship between Market Orientation and Green Product Innovation: The Intervening Role of Green Self-Efficacy and Moderating Role of Resource Bricolage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, Z. Frugal-based innovation model for sustainable development: Technological and market turbulence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 42, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Huang, H.-C. How global mindset drives innovation and exporting performance: The roles of relational and bricolage capabilities. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, J.T.; Chandler, G.N.; Markova, G. Entrepreneurial effectuation: A review and suggestions for future research. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 2012, 36, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Chen, J.; Mei, L.; Wu, Q. How leadership matters in organizational innovation: A perspective of openness. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, G.; Xie, H. Impacts of leadership on project-based organizational innovation performance: The mediator of knowledge sharing and moderator of social capital. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, S.; Whiteman, G.; van den Ende, J. Radical innovation for sustainability: The power of strategy and open innovation. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, P.; Liu, L.; Tan, J. The influence of organisational justice and ethical leadership on employees’ innovation behaviour. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership for sustainability: An evolution of leadership ability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Lu, X. Do ethical leaders give followers the confidence to go the extra mile? The moderating role of intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2016, 135, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O. Ethical leadership influence at organizations: Evidence from the field. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Casey, T. How and when organization identification promotes safety voice among healthcare professionals. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3733–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, M. The influence of responsible leadership on environmental innovation and environmental performance: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, G.; Albitar, K. Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, Y. Has technological innovation capability addressed environmental pollution from the dual perspective of FDI quantity and quality? Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, P.; Jindal, M.; Jindal, T. A review on economically-feasible and environmental-friendly technologies promising a sustainable environment. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, P.; Diener, D.; Harris, S. Circular products and business models and environmental impact reductions: Current knowledge and knowledge gaps. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhro, S.M.; Aulia, A.F. New Sources of Growth: The Role of Frugal Innovation and Transformational Leadership. Bull. Monet. Econ. Bank. 2004, 22, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nazir, S.; Shafi, A.; Asadullah, M.A.; Qun, W.; Khadim, S. How does ethical leadership boost follower’s creativity? Examining mediation and moderation mechanisms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1700–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laajalahti, A. Fostering creative interdisciplinarity: Building bridges between ethical leadership and leaders’ interpersonal communication competence. In Public Relations and the Power of Creativity; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Giudice MDel Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Mirza, B.; Jamil, A. The influence of ethical leadership on innovative performance: Modeling the mediating role of intellectual capital. J. Manag. Dev. 2021, 40, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, T.; Keller, R.T. Leadership in research and development organizations: A literature review and conceptual framework. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Banerjee, P.; Sweeny, E. Frugal Innovation: Core Competencies to Address Global Sustainability. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain. 2013, 1, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, P.; Krishnan, R.T. Frugal innovation: Aligning theory, practice, and public policy. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2014, 6, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, G. Resource mobilization in international social entrepreneurship: Bricolage as a mechanism of institutional transformation. Entrep. theory Pract. 2012, 36, 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, Z.; Ahlstrom, D. Business model innovation: The effects of exploratory orientation, opportunity recognition, and entrepreneurial bricolage in an emerging economy. Asia. Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyard, J.; Baker, T.; Steffens, P.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a path to innovativeness for resource-constrained new firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinello, E.; Tontini, G.; Alberton, A. Influence of maturity on corporate social responsibility and sustainable innovation in business performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, V.F.; de la Hiz, D.I.L. Lessons on Frugal Eco-Innovation: More with Less in the European Business Context, the Critical State of Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe (Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmelly, R.; Ray, P.K. Managing resource-constrained innovation in emerging markets: Perspectives from a business model. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Xie, M. Can direct environmental regulation promote green technology innovation in heavily polluting industries? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 140810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Xie, X.M.; Qi, G.Y. The impact of product market competition on corporate environmental responsibility. Asia. Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, T.; Chen, Y.; Carmeli, A. CEO environmentally responsible leadership and firm environmental innovation: A socio-psychological perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, S.; Chadee, D.; Sun, C. The influence of exploitative leadership on hospitality employees’ green innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Tang, G.; Cooke, F.L. High-commitment work systems and middle managers’ innovative behavior in the Chinese context: The moderating role of work-life conflicts and work climate. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Z.; Dou, W.; Wang, F. Flying or dying? Organizational change, customer participation, and innovation ambidexterity in emerging economies. Asia. Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Invest. Anal. J. 2016, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.F.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Ma, X. The effect of CEO entrepreneurial orientation on firm strategic change: The moderating roles of managerial discretion. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2021, 59, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2017; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. Sustainable development goals and progressive business models for economic transformation. Local Econ. 2019, 34, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable business models: A review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marczewska, M.; Kostrzewski, M. Sustainable business models: A bibliometric performance analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuscher, K.; Abdelkafi, N. Scalability and robustness of business models for sustainability: A simulation experiment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pasricha, P.; Rao, M.K. The effect of ethical leadership on employee social innovation tendency in social enterprises: Mediating role of perceived social capital. Create. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Ha, A.T.L.; Le, P.B. How ethical leadership cultivates radical and incremental innovation: The mediating role of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 35, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, I.; Ahmad, B.; Kalyar, M.N. How ethical leadership influences creativity and organizational innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and the role of responsible leadership in health care: Thinking beyond employee well-being and organisational sustainability. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2021, 34, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, N.I.; Asad, H.; Hussain, R.I. Environmental innovation and financial performance: Mediating role of environmental management accounting and firm’s environmental strategy. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2020, 14, 715–737. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. How resource alignment moderates the relationship between environmental innovation strategy and green innovation performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijethilake, C.; Munir, R.; Appuhami, R. Environmental innovation strategy and organizational performance: Enabling and controlling uses of management control systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Othman, M.S.H.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P. The moderating role of environmental management accounting between environmental innovation and firm financial performance. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2018, 19, 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, A.; Auer, A. Corporate Environmental Innovation (CEI): A government initiative to support corporate sustainability leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Al-Hawari, M.A.; Mohd Shamsudin, F. Green innovation performance: A multi-level analysis in the hotel sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J.; Sarwar, H.; Kiran, A.; Qureshi, M.I.; Ishaq, M.I.; Ambreen, S.; Kayani, A.J. Ethical leadership, workplace spirituality, and job satisfaction: Moderating role of self-efficacy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Du, T.; Nguyen, T.T. Can both entrepreneurial and ethical leadership shape employees’ service innovative behavior? J. Serv. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.J. The Effect of Ethical Leadership on Organizational Performances. Int. Inf. Inst. (Tokyo) Inf. 2015, 18, 2241. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.N.H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. To walk in beauty: Sustainable leadership, frugal innovation and environmental performance. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. International entrepreneurial marketing strategies of MNCs: Bricolage as practiced by marketing managers. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Constructs | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| Ethical Leadership | 3.790 | 0.302 | −0.471 | 0.138 | 0.163 | 0.275 |

| Environmental Innovation | 3.832 | 0.304 | −0.300 | 0.138 | 1.867 | 0.275 |

| Entrepreneurial Bricolage | 3.814 | 0.379 | −0.591 | 0.138 | 1.392 | 0.275 |

| Sustainable Performance | 3.847 | 0.378 | 0.048 | 0.138 | 2.121 | 0.275 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership | EL10 | 0.609 | 0.924 | 0.932 | 0.606 |

| EL02 | 0.706 | ||||

| EL03 | 0.821 | ||||

| EL04 | 0.765 | ||||

| EL05 | 0.799 | ||||

| EL06 | 0.837 | ||||

| EL07 | 0.822 | ||||

| EL08 | 0.769 | ||||

| EL09 | 0.847 | ||||

| Environmental Innovation | EI01 | 0.874 | 0.919 | 0.943 | 0.804 |

| EI02 | 0.889 | ||||

| EI03 | 0.923 | ||||

| EI04 | 0.901 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Bricolage | EB01 | 0.715 | 0.928 | 0.937 | 0.623 |

| EB03 | 0.627 | ||||

| EB04 | 0.864 | ||||

| EB05 | 0.872 | ||||

| EB06 | 0.85 | ||||

| EB07 | 0.842 | ||||

| EB08 | 0.852 | ||||

| EB09 | 0.814 | ||||

| Social Performance | SOP01 | 0.89 | 0.931 | 0.944 | 0.808 |

| SOP02 | 0.894 | ||||

| SOP03 | 0.882 | ||||

| SOP04 | 0.908 | ||||

| SOP05 | 0.921 | ||||

| Economic Performance | ECP01 | 0.291 | 0.763 | 0.844 | 0.541 |

| ECP02 | 0.805 | ||||

| ECP03 | 0.712 | ||||

| ECP04 | 0.844 | ||||

| ECP05 | 0.868 | ||||

| Environmental Performance | ENP01 | 0.913 | 0.829 | 0.836 | 0.573 |

| ENP02 | 0.897 | ||||

| ENP03 | 0.516 | ||||

| ENP05 | 0.623 | ||||

| Sustainable Performance | SOP | 0.844 | 0.829 | 0.832 | 0.631 |

| ECP | 0.923 | ||||

| ENP | 0.574 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial bricolage | 0.789 | |||

| Environmental innovation | 0.704 | 0.897 | ||

| Ethical leadership | 0.564 | 0.633 | 0.778 | |

| Sustainable performance | 0.493 | 0.438 | 0.756 | 0.794 |

| Hypotheses | β | S.D | T Stat | p Values | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership > Environmental Innovation | 0.593 | 0.110 | 5.404 | 0.000 | 0.449 | 0.768 |

| Environmental Innovation > Sustainable Performance | 0.515 | 0.060 | 8.548 | 0.000 | 0.450 | 0.648 |

| Ethical Leadership > Environmental Innovation > Sustainable Performance | 0.294 | 0.063 | 4.689 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.423 |

| Ethical Leadership * Bricolage > Environmental Innovation | 0.146 | 0.082 | 1.782 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.258 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xuecheng, W.; Iqbal, Q. Ethical Leadership, Bricolage, and Eco-Innovation in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127070

Xuecheng W, Iqbal Q. Ethical Leadership, Bricolage, and Eco-Innovation in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127070

Chicago/Turabian StyleXuecheng, Wei, and Qaisar Iqbal. 2022. "Ethical Leadership, Bricolage, and Eco-Innovation in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127070

APA StyleXuecheng, W., & Iqbal, Q. (2022). Ethical Leadership, Bricolage, and Eco-Innovation in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: A Multi-Theory Perspective. Sustainability, 14(12), 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127070