Consuming Location: The Sustainable Impact of Transformational Experiential Culinary and Wine Tourism in Chianti Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction & Objective

1.1. Hopeful Tourism: Transformational Experiences

1.2. Storytelling

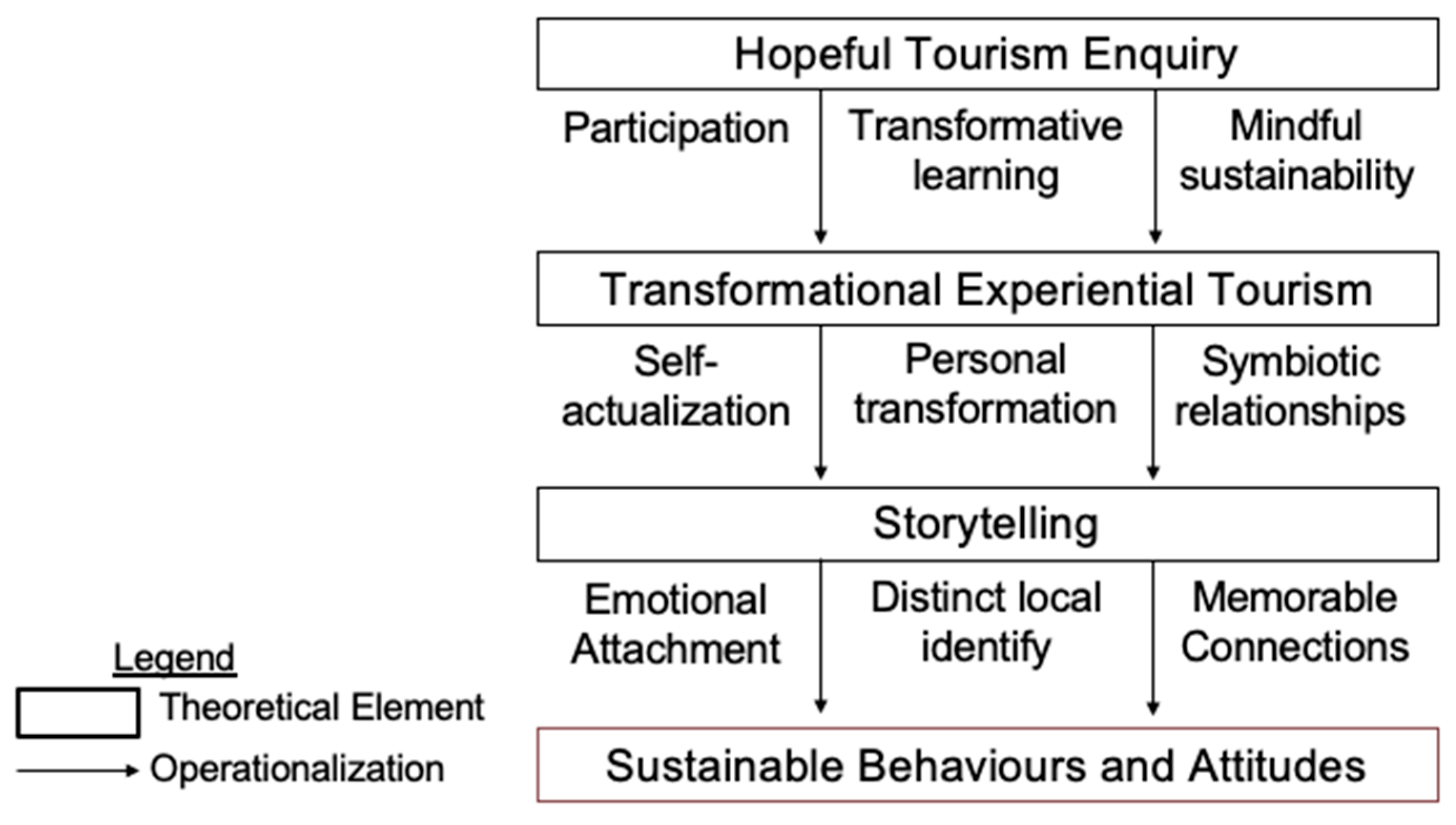

1.3. Summary of Conceptual Framework

2. Materials and Methods

Study Area: Castello Sonnino

3. Results

3.1. Consumption of Place through Storyscapes

“You get to have a comparison across different [wines] for these three years. They’ll taste completely different not because it’s a different blend or a different type of grape it’s just because you know it was rainy, it was very sunny, you know they’re more rocks, fewer rocks like his you could taste it.”Student Focus Groups

“And then we went there, and he literally takes the wine out of the barrel and just hands around a glass. So, everyone, like you see like the difference in how… they want to present the wine, like who they’re directing it towards”Student Focus Groups

“The wine was served in glass pitchers without any context or information because the winemaker told [us] he did not want them to judge the wine based on the label, bottle, vintage, or varietal. Instead, he told [us] he wanted to judge the wine based on ‘taste and feel’.”Student Focus Groups

“Sustainability means social…making food for other people, caring for others, environment, building positive community.”Industry Interview

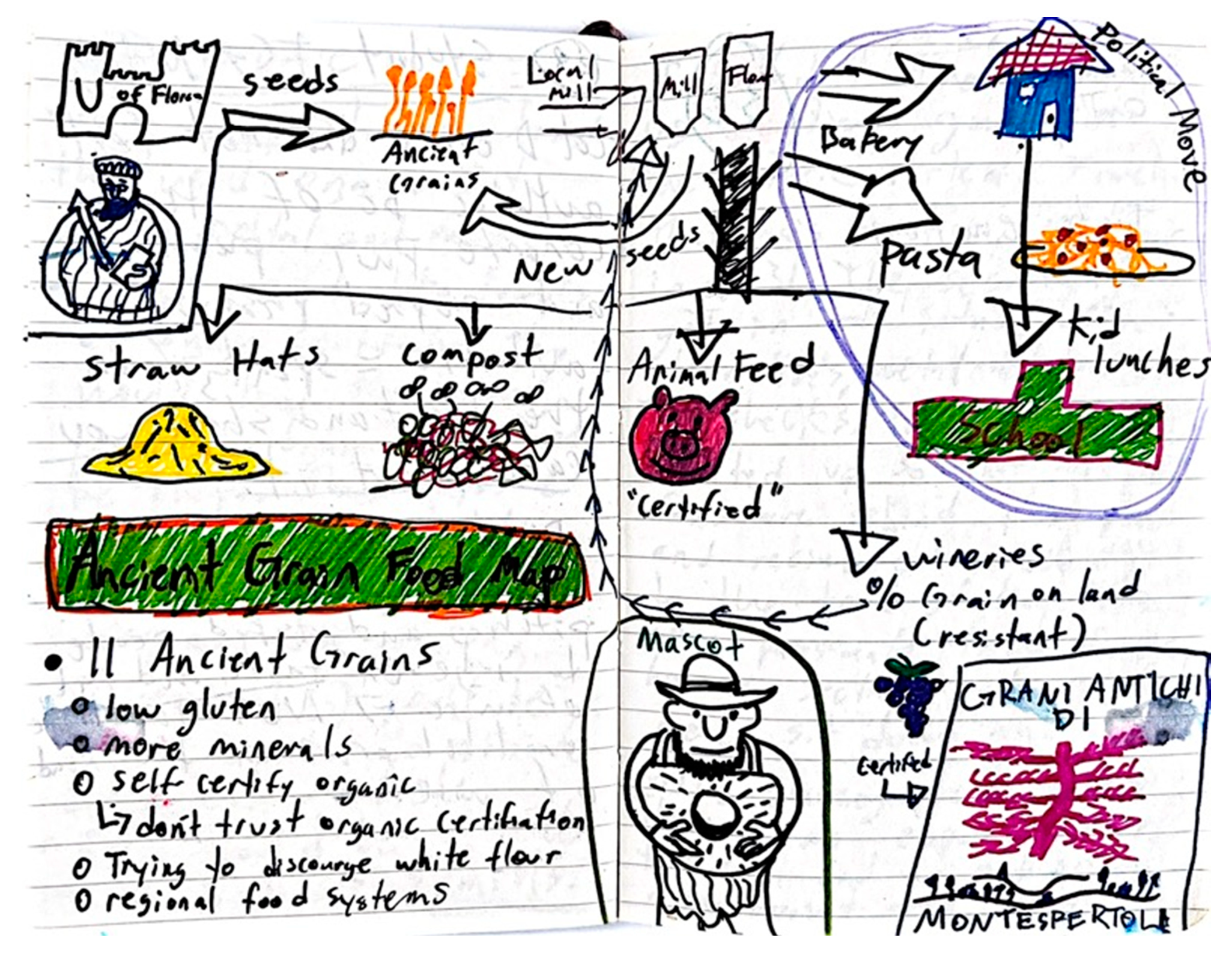

3.2. Wine Is Food Culture: Achieving Sustainability through Local Circular Economies

“I don’t know, like just being here, I realized all the ingredients are a lot … less processed, I feel like their tomato sauces taste a lot better. Like, I understand that the grains are a lot better for us. So … if you think about that aspect, then you would assume the wines are organic, or better quality than what we would have back in North America.”Student Focus Groups

“The way they did the things that they’re trying to do [and] they’ve accomplished like using the old grain and the biscuits … I found it was very very innovative and I’m thinking … it was kind of much more … traditional since there’s still a very luxurious feeling to it which is like, I mean, I think in terms of like what a lot of tourists come looking for.”Student Focus Groups

“And even food here is, like, more appreciated. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s more proportion and it’s more of an experience instead of just like the act of consuming and filling your stomach”Student Focus Groups

“… wine has become kind of synonymous with wealth, so if you’re looking at the difference between the peasant wine and that kind of thing, it is really interesting because it shows the roots of wine and how wine was always something that was driven by everyone and was consumed by everyone no matter what their social status was”Student Focus Groups

“I think, like, the wine guys here do their best or at least are more aware of sustainability, not just in the environmental sense but also in the social and the economic sense as well. Even with things, not just the winery, but like with the meal, for example, [they] wanted … a situation … where like the people producing it can afford to buy it.”Student Focus Group

3.3. Consumption of Location: Drinking a Memory

“I don’t know, I felt their [bio-dynamic] wine is a lot smoother.”Student Focus Groups

“The wine becomes nostalgic, like your grandma’s cookies”.—student

“Wine is the only food product that can transcend time and space.”Industry Interview

4. Discussion Conclusions

5. Limitations & Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thanh, T.V.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Belk, R.W.; Charters, S.; Feng Wang, J.; Pena, C. Performance Theory and Consumer Engagement: Wine-Tourism Experiences in South Africa and India. In Consumer Culture Theory; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. The transformational power of wine tourism experiences: The socio-cultural profile of wine tourism in South Aus-tralia. In Social Sustainability in the Global Wine Industry; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, A. Social Entrepreneurship in Tourism: The Conscious Travel Approach; TIPSE: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brunori, G.; Galli, F. Sustainability of Local and Global Food Chains: Introduction to the Special Issue. Sustainability 2016, 8, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbo, C.; Lamastra, L.; Capri, E. From Environmental to Sustainability Programs: A Review of Sustainability Initiatives in the Italian Wine Sector. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moscovici, D.; Reed, A. Comparing wine sustainability certifications around the world: History, status and opportunity. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Sustainable Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D. Can sustainable tourism survive climate change? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Asymmetrical dialectics of sustainable tourism: Toward enlightened mass tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Advanced Introduction to Sustainable Tourism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, B.A.; Senese, D.M. Competitiveness and Sustainability in Wine Tourism Regions: The Application of a Stage Model of Destination Development to Two Canadian Wine Regions. In The Geography of Wine; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. Rural Wine and Food Tourism for Cultural Sustainability. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. Rural Food and Wine Tourism in Canada’s South Okanagan Valley: Transformations for Food Sovereignty? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Fountain, J. Characterising resilience in the wine industry: Insights and evidence from Marlborough, New Zealand. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 94, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M.; Ioannides, D. Threats and obstacles to resilience: Insights from Greece’s wine tourism. In Tourism, Resilience and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.A.; Bowyer, E. Tourism and sustainable transformation: A discussion and application to tourism food consumption. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 45, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N.; Ateljevic, I. Hopeful Tourism: A New Transformative Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 941–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senese, D.M. Transformative wine tourism in mountain communities. In Mountain Tourism: Experiences, Communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Laing, J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. What is Positive Tourism? Why do we need it? In Positive Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. The Transformative Power of the International Sojourn: An Ethnographic Study of the International Student Ex-perience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L.; Stoner, L.; Tarrant, M. More Than a Vacation: Short-Term Study Abroad as a Critically Reflective, Transformative Learning Experience. Creative Educ. 2012, 3, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mair, H.; Sumner, J. Critical tourism pedagogies: Exploring the potential through food. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Benckendorff, P. Travel and Learning: A Neglected Tourism Research Area. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, J.; Senese, D.; Hull, J.S. Fruit Forward?: Wine Regions as Geographies of Innovation in Australia and Canada. In Regional Cultures, Economies, and Creativity; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Senese, D.M.; Hull, J.S.; McNicol, B.J. Ecotopian mobilities: Terroir-driven tourism and migration in British Columbia, Canada. In Wine, Terroir and Utopia; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, T.H. Opportunities and Pitfalls of Tourism in a Developing Wine Industry. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1995, 7, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Frost, J.; Strickland, P.; Maguire, J.S. Seeking a competitive advantage in wine tourism: Heritage and storytelling at the cellar-door. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, D.W. Tradition, Territory, and Terroir in French Viniculture: Cassis, France, and Appellation Contrôlée. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 848–867. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, G.; Clark, G.; Oliver, T.; Ilbery, B. Conceptualizing Integrated Rural Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouma, G.D.; Ling, R.; Wilkinson, L. The Research Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Senese, D.M.; Hull, J.S.; Caton, K. Introduction to the Special Issue: Wine and Culinary Tourism Futures. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, J.K. Environmental Sustainability: The Art and Science. In Futures Research and Environmental Sustainability; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.J.; Roberts, A.; Nelson, P. Ethnographic landscapes. CRM-WASHINGTON 2001, 24, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. The Travel Journal: An Assessment Tool for Overseas Study. Occasional Papers on International Educational Exchange; Department Council on International Educational Exchange: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Version 12. 2018. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Camerana, B. Castello Sonnino ‘Living History to Sustain the Future’; A Plan for Academic Development: Montespertoli, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Azzari, M.; Rombai, L. La Toscana Della Mezzadria. Paesaggi delle Colline Toscane; Marsilio Editori: Venezia, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis, A. Coconstructing heritage at the gettysburg storyscape. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, L. Extraordinary Experiences through Storytelling. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassano, C.; Barile, S.; Piciocchi, P.; Spohrer, J.C.; Iandolo, F.; Fisk, R. Storytelling about places: Tourism marketing in the digital age. Cities 2018, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Fountain, J.; Fish, N. “You Felt like Lingering…” Experiencing “Real” Service at the Winery Tasting Room. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. The Shaping of Tourist Experience: The Importance of Stories and Themes. Tour. Leis. Exp. Consum. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 44, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain, J.; Charters, S.; Cogan-Marie, L. The real Burgundy: Negotiating wine tourism, relational place and the global countryside. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 23, 1116–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessiere, J. Local Development and Heritage: Traditional Food and Cuisine as Tourist Attractions in Rural Areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, S.; Aitchison, C. The Role of Food Tourism in Sustaining Regional Identity: A Case Study of Cornwall, South West England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, J.A.; Shin, H.J.; Lee, S.-H. Traveler sensoryscape experiences and the formation of destination identity. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 24, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R. From agricultural to rural: Agritourism as a productive option. In Food, Agriculture and Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, S.L. Local Food: Greening the Tourism Value Chain. In Tourism in the green economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, S.L. Placemaking through Food: Co-Creating the Tourist Experience. Creative Tourism in Smaller Communities; University of Calgary Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2021; pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Mascarilla-Miró, O. Wine lovers: Their interests in tourist experiences. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.; Sykes, C. Concepts of Time and Temporality in the Storytelling and Sensemaking Literatures: A Review and Cri-tique. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flint, D.J.; Golicic, S.L. Searching for Competitive Advantage through Sustainability: A Qualitative Study in the New Zealand Wine Industry. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades, L.; Dimanche, F. Co-creation of experience value: A tourist behaviour approach. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism, 2nd ed.; CABI: Boston, MA, USA; Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, O. Photography and travel brochures: The circle of representation. Tour. Geogr. 2003, 5, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, N. The Art and Craft of Storytelling: A Comprehensive Guide to Classic Writing Techniques; Penguin: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, R.D. Food, Orality, and Nostalgia for Childhood: Gastronomic Slavophilism in Midnineteenth-Century Russian Fiction. Russ. Rev. 1999, 58, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Nostalgia and Consumption Preferences: Some Emerging Patterns of Consumer Tastes. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diţoiu, M.-C.; Stăncioiu, A.-F.; Brătucu, G.; Onişor, L.-F.; Botoș, A. The Sensory Brand of the Destination. Case Study: Tran-sylvania. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2014, 21, 594. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P.O.D.; Scott, N. Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R. Empowering the new traveller: Storytelling as a co-creative behaviour in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 20, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphim, J.; Haq, F. Designing in the United Arab Emirates. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esau, D.; Senese, D.M. Consuming Location: The Sustainable Impact of Transformational Experiential Culinary and Wine Tourism in Chianti Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127012

Esau D, Senese DM. Consuming Location: The Sustainable Impact of Transformational Experiential Culinary and Wine Tourism in Chianti Italy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127012

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsau, Darcen, and Donna M. Senese. 2022. "Consuming Location: The Sustainable Impact of Transformational Experiential Culinary and Wine Tourism in Chianti Italy" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127012

APA StyleEsau, D., & Senese, D. M. (2022). Consuming Location: The Sustainable Impact of Transformational Experiential Culinary and Wine Tourism in Chianti Italy. Sustainability, 14(12), 7012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127012