The use of English, which is a foreign language to NPTI (Noble Private Technical Institute) in Erbil city, Northern Iraq, is a significant component of contemporary cultures. In a large number of workplaces and educational institutions, English is a first or second language that is spoken globally. The acceptance rate of English-medium institutions is higher than that of local language institutions. According to Bohara [

1], English is the language of communication for the majority of societies.

Listening, speaking, reading, and writing are all essential for learning English. In societies where it is not extensively spoken or utilized, English is typically difficult to learn and teach. According to Smith, et al. [

2], the most difficult task for English as a foreign language teacher in developing and underdeveloped nations is determining the most effective method of instruction. Effective English language training also requires instructor motivation, student motivation, and students’ learning capacity in addition to textual knowledge [

3].

Throughout the last few decades, numerous studies have described various approaches and methodologies for teaching English as a second (ESL) or foreign language (EFL), such as task-based learning, audio-lingual learning, communicative language teaching, neutral instruction, content-based instruction, grammar-translation method, and direct method, with the oral approach added on top. They can be used for a variety of reasons, such as investigating, predicting, or describing a foreign language [

4].

It is no longer possible to avoid studying English as a second language (ESL) because English has become the dominant language, particularly in academic settings. Our research strives to incorporate technology and contemporary tools into the teaching and learning process in order to promote effective and enduring learning [

5]. As with any other language, English requires a great deal of focus. Instead of focusing on societal concerns, this study evaluated the teaching of English as a language by making it more engaging as a work of art [

6].

There is a paucity of responsive tactics and procedures for enhancing the English vocabulary of students at technical institutes/universities in northern Iraq and at the Noble Technical Private Institute in Erbil [

7]. Despite choosing English as the medium of instruction, even students in the English education department lack the ability to play with English vocabulary, which is essential for learning English as a second language (ESL) and for communicating, understanding, and writing successfully [

8].

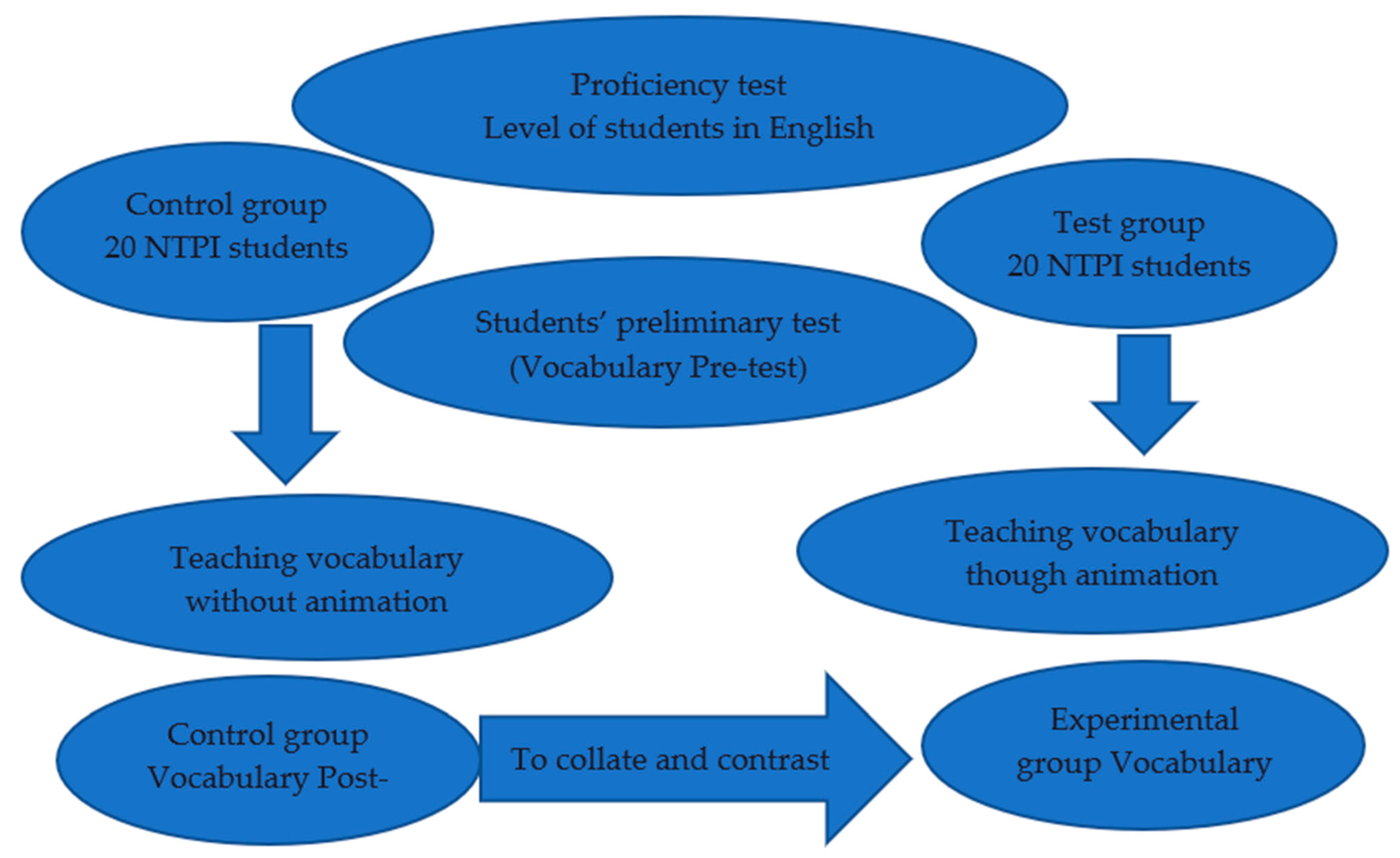

As a result, this study’s methodology used technological instruments for innovative learning. Using a series of animated videos, this research assesses the usefulness of using technology in northern Iraq for mid-career learners. This project aims to improve the manner in which students learn English by employing more adaptable teaching strategies and by encouraging lasting knowledge.

1.1. Research Objectives

Students at the Noble Technical Private Institute/Northern part of Iraq-Erbil city participated in the study with the purpose of analyzing the effectiveness of animated video methods in vocabulary learning. Our research study had several particular objectives:

The purpose of this study is to determine the student performance at Noble Technical Private Institute in Northern Iraq-Erbil, with animated video.

This study aimed to assess the performance of students at Noble Technical Private Institute in Northern Iraq-Erbil who were not taught with animation.

This study aimed to explore the efficacy of animated videos in enhancing English vocabulary learning.

A comparison between student performance after animated video and without animated video at Noble Technical Private Institute in Northern Iraq-Erbil.

1.5. Research Study Theoretical Framework

The majority of schools today teach English because it has become a global language. Vocabulary is a vital part of language for language learners, as communication is impossible without it. Indeed, vocabulary knowledge is a critical instrument for acquiring communicative competence in any language for second language learners.

Improving one’s language comprehension and associated vocabularies on a regular basis is necessary for acquiring an outstanding command of a language. In the majority of situations, especially in Arab-speaking nations, English is a second language, necessitating effort and dedication to ensure students’ comprehension of the language and mastering of new vocabularies. As a form of instructional design, annotations play a crucial role in facilitating reading comprehension and vocabulary development while learning foreign languages.

According to Al-Akraa [

9], multimedia learning, which comprises the complementary use of images and words in the learning process, has been utilized for decades and has therefore proven ineffective in accomplishing certain learning objectives and goals. Studies conducted by Copland, et al. [

10] and Baarda [

11] reveal a positive correlation between multimedia learning and the ease of comprehension and understanding of English language learners of new, unfamiliar vocabulary. Over the years, educators have struggled to create a balance between different multimedia annotations so that different media, such as pictures, videos, audio, and texts, are combined in order to assist English language learners in comprehending and understanding new and unfamiliar English vocabulary words.

Aldera and Mohsen [

12] suggests that the combination of textual definition and images plays a crucial role in facilitating good mastering of new vocabulary compared to the usage of individual multimedia annotations such as images or textual definitions. In addition, the article says that the successful usage of mixed multimedia annotations such as audios and videos in assisting students to acquire and comprehend new language vocabulary of a second or foreign language is due to the incorporation of meaning-rich contexts and conversation. Animated videos have the potential to contextualize new language, making it easier for learners to comprehend and comprehend the meaning of the new word. Many research on sustainable development have been published, although the majority of them focus on single objectives such as education, health, or gender equality [

13,

14].

Horst and Meara [

15] defined productive knowledge as the ability to recall and retain previously taught information, including a term or definition from a vocabulary standpoint, based on their definition. Webb [

16] does not place this concern on a learner’s ability to write the word in its unique context, contrary to Meiri, et al. [

17] contention. In contrast, receptive vocabulary refers to words directly comprehended from hearing, seeing, or reading [

18]. Therefore, when learning new words, the knowledge curve begins with receptive vocabulary and proceeds to productive vocabulary, the latter of which is more complex.

In addition, animated videos contextualize new words and their definitions, followed by graphical definitions, which all play a crucial part in assisting students to comprehend difficult words. In addition, animated videos typically feature engaging, colorful characters and environments that have been catching the attention of students and extending their ability to concentrate. Some scholars, however, associate the use of animated videos in learning new vocabularies with distractions, noting that animated videos divert learners’ attention from the actual vocabulary to the interesting illustrations and characters, in primary school students, thereby impeding their ability to comprehend new vocabularies. Consequently, it is crucial to conduct an empirical investigation to determine the efficacy of animated videos in language acquisition in university students as this study tries to emphasize.

The latter demands excellent communication and the ability to articulate ideas, opinions, and thoughts. Those learning a second language can be instructed in a variety of methods. There are numerous types of animation, including cartoons and videos, books, essays, and online training [

19]. Although there are many of these forms available, they may not always be sufficient; therefore, the makers must tailor the learning aids to the learner’s needs. Language serves to facilitate communication between individuals [

20].

The use of multimedia in English language instruction is widespread in the modern digital era, with animated videos associated with rapid acquisition of new vocabulary. According to Akhtar [

21], the usage of animated videos in English learning has resulted in the establishment of more colorful and engaging learning environments, as well as the provision of support for the vocabulary learning processes of students. Learning and comprehending new vocabularies is a time-consuming process that requires looking up the definitions of a large number of terms in text-based dictionaries, hence reducing the likelihood of learning and mastering vocabulary. Due to this ambiguity, the incorporation of animated videos as a means of acquiring new terminology is crucial. Sustainable development objectives can be promoted through mobile technologies, such as smartphone applications.

Baarda [

11] argues that the use of animated videos to introduce new vocabulary is beneficial due to their interactivity and capacity to appeal to the majority of our senses while also introducing relevant situations for these new words.

1.6. The Importance of Videos for Teaching and Learning

There are many ways to teach English as a foreign language, which makes analyzing their effectiveness difficult [

2]. There are various ways of teaching the English Language, both theoretically and in practice around the globe. However, visual techniques have a greater impact on students than written ones [

22,

23,

24]. In the study carried out by D’Mello [

25], it was observed that learners who were exposed to graphical and creative learning methods learned the concepts more quickly and easily [

25,

26].

Copland, Garton and Burns [

10] in their study on the effectiveness of using animated videos in teaching second languages showed that animated videos and English TV programs played a crucial role in enhancing the understanding of English language by learners who watched the videos. The study reported that learners who watched animated English videos and other related TV programs with subtitles performed better in oral translation tests as compared to other learners that solely relied on static learning materials.

According to Bocanegra-Valle [

27] the general use of audio visions such as animated videos in the classroom has gained prominence as a reliable tool for teaching second languages and mastering new vocabularies. In a study conducted by Mubarok, et al. [

28] on Dutch-speaking universities, students reported that learners who admitted to being fond of watching English animated videos scored better grades in English subjects as compared to other learners that solely relied on static images and textual definitions.

A meta-analysis conducted by Akhtar [

21] on 37 studies presented similar results in which technology-supported language learning is more effective and impactful as compared to traditional learning modes. The results of this study showed that the use of animated videos in learning second languages and vocabulary was more effective as compared to learning with instructions without the use of videos.

Moreover, Dzebeq, et al. [

29] researched the same matter on 60 students in the 10th grade, divided into both control and experimental groups. 3o students were assigned as the control group as they did not participate in the animated video lessons compared to the other 30 students who learned through animated videos. The results showed a significant positive outcome of vocabulary learning through animated videos.