1. Introduction

Oftentimes, (small) islands are forgotten in the capitalist world, especially in developing countries—in terms of both spatial and aspatial development—unless they bring a tangible large economic benefit. Further, a hegemony of spaces, since the ‘neoliberal sphere’ in policy-making of the 1980s, drove authorities and governing elites to economics, and pro-growth logics of development over social and welfare concerns [

1]. Consequently, and in parallel with these dynamics, growing social exclusion and polarisation often remained unaddressed by governments as a top decision maker [

2]. This occurred mainly on small islands; most rural areas of small islands were left untouched by government policies or development support. Unless (small) islands bring an economic benefit/income to the regions/provinces in terms of GDP (such as through tourism), they would be less prioritised on the government’s development agenda. As a result, inhabitants of small islands often live a ‘survivor-of-the-fittest’ lifestyle due to their insularity—being cut-off from the nearest mainland geographically, economically, socially, or culturally, by the water. They must battle for their survival on their own.

For a long period of time, (small) islands have attracted the interest of stakeholders from outside island communities (NGOs, private sector, or government) because of their image of being an earthly paradise owing to their natural beauty and cultural potential, regardless of their geographical and spatial insularity or inherent “islandness” [

3,

4,

5]. The attention of stakeholders was primarily drawn by tourism. Some researchers have even stated that small islands are often monetised by tourism activities [

6,

7] such as (community-based/indigenous) ecotourism, cruise tourism, adventure tourism, and other forms of tourism. Numerous (small) islands in the world have been transformed into tourist destinations in order to capitalise on market potential and improve islanders’ economies [

8]. Besides ‘profit-seeking’ actors, NGOs and academics generally assess the potential of small islands from a social and local welfare perspective, attempting to empower communities and mobilize their participation rather, than focusing exclusively on islands’ economic potential or regional income. They assist an island’s inhabitants in transforming the (small) island and the inhabitants, regardless of the other interests they pursue with the support of donors or grant funds [

9,

10,

11]. The trajectory of emerging community-based ecotourism on small islands is further highlighted here. It is viewed as a viable alternative to extractive land uses such as farming, logging, or others, because it involves the local community in the management of tourism, culture, and the environment. It transforms a subsistence lifestyle and aids in the transition to leverage a cash economy for the local community [

10].

Often, the transformation of an island into a tourism site begins with immaterial development, specifically, by building the capacity of inhabitants, empowering them with skills and knowledge to build a sustainable environment [

10]. Capacity building is inextricably linked to the active participation of local communities, which is deemed to be important for guaranteeing sustainability. Regrettably, true active participation or empowerment has received scant attention in the tourism-development literature [

12,

13]–or even in the literature on small-island tourism—thus far [

14]. Researchers have shown that focusing on material development per se (infrastructure, transportation, utilities, accommodation, and other physical developments), results in islands’ unsustainable development in the future, which is worsened by uninvolved inhabitants in development practices [

15,

16]. Indeed, it still offers fast benefits economically, but generally, for a short period of time. Meanwhile, participation (in tourism) has a considerable positive effect on the perceptions and behaviours of local operators/communities regarding environmental conservation [

17]. Improving human-resources skills, knowledge, and a sense of belonging through community capacity building is an immaterial development that ‘puts people first’ in order to create a ‘healthy economy’ that enables people to participate in deciding what they can do and be in their lives or livelihoods now and in the future [

18].

In a broader context, researchers have noted that active engagement is frequently limited by a community’s lack of information and understanding, confidence, time, and interest [

12,

19], as well as a lack of ownership, capital, and skills [

19]. These limits are frequently encountered by indigenous peoples/inhabitants on small islands. While some scholars have examined the transformation of small islands into (eco)tourism or community-based ecotourism (CBE), and their impact and governance, little is known about local communities’ innovative initiatives in developing their capacity, and becoming capital by transforming a small island into an ecotourism destination with the assistance of ‘non-profit-seeking’ external actors (NGOs and academics). More knowledge is also needed about tensions that arise in tackling environmental issues and political empowerment [

20,

21]. This paper investigates a small island’s transformation through capacity building in/by local initiatives, bottom-linked governance, and increased political bargaining power. It discusses the following research questions in detail: (1) To what degree and in what ways are local actors (inhabitants of the island and non-governmental organisations) capable of building capacity for a process of transformation and institutional innovation, enabling empowerment mechanisms and enhanced bargaining power? (2) How do they resolve and manage conflicts involving environmental issues and tourism development, as well as foster bottom-linked governance?

To address these questions, we devised a three-tiered analytical framework, explained in

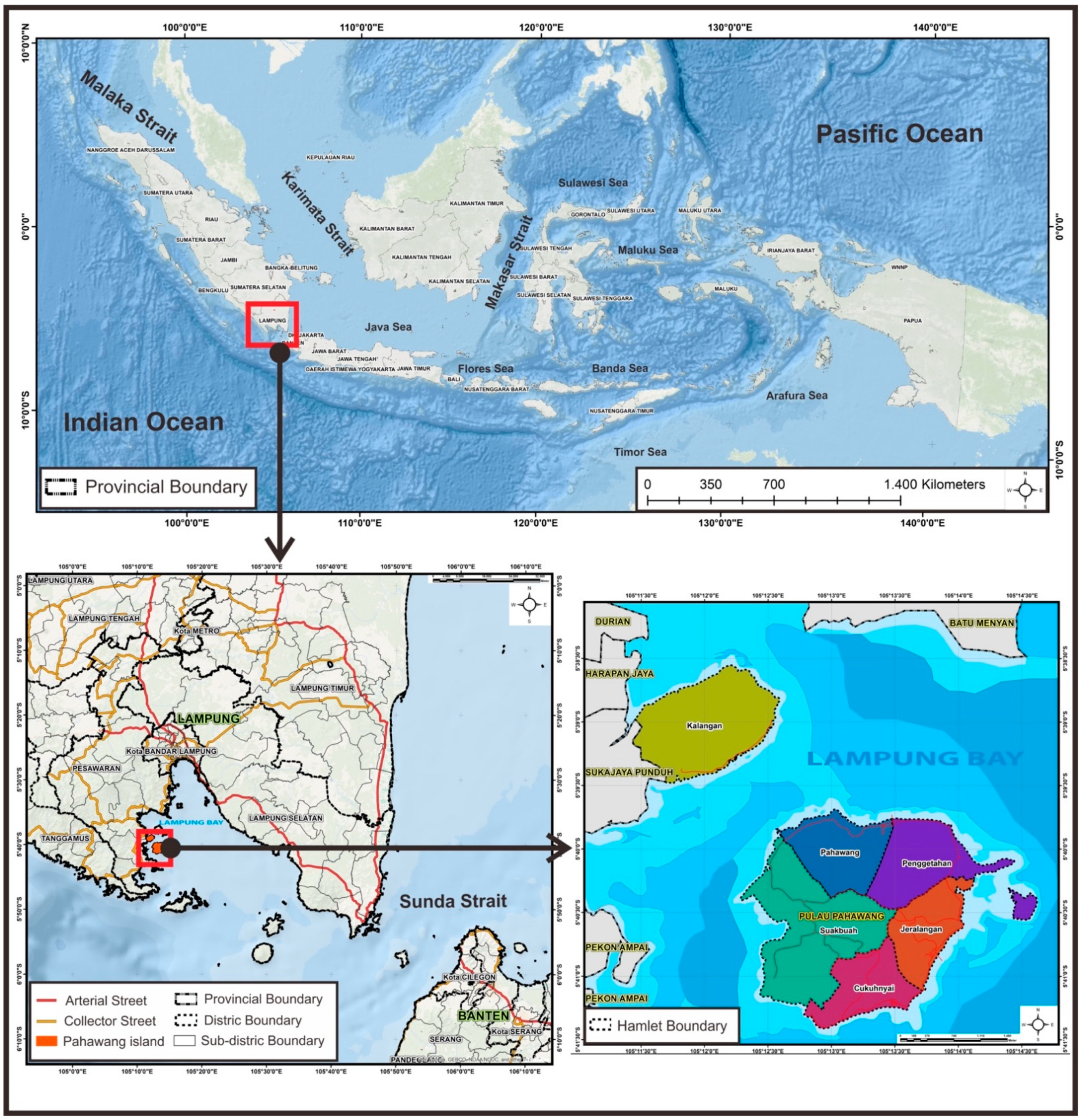

Section 2, that combines capacity building, social innovation (in the direction of bottom-linked governance), and (political) bargaining power. This framework was used to analyse metamorphosis and innovative efforts undertaken by the island’s people and “non-profit-seeking” actors acting as “agents of change”, on a small rural island in Southeast Asia (Indonesia) between 1997 and 2014.

Section 3 introduces the case study and the technique used to analyse it.

Section 4 presents the results. These are further discussed in

Section 5, followed by the conclusions that capacity building was embedded in social innovation, bottom-linked governance and increased political bargaining power. That is when capacity building is ‘dynamized’ and can play a role in sustainable island transformation. Under these conditions, collaborative grassroots learning, and action efforts, can be a virtuous panacea for improving the sustainable governance of small islands. This article will contribute to the growing body of knowledge on community capacity building, social innovation towards alternative governance, and (political) bargaining power in the setting of small islands, by examining empirical evidence from a small rural island in a global-south country that is yet little explored [

14].

2. Dynamizing Capacity Building in the Context of Small Islands

In defining islands, particularly small ones, this paper will restrict itself to the definition of a small, inhabited island. The one mentioned by Péron is:

“Those specks of land large enough to support permanent residents, but small enough to render to their inhabitants the permanent consciousness of being on an island… The maritime barrier is always there, solid, totalising and domineering, tightening the bonds between the island folk, who thus experience a stronger sense of closeness and solidarity.”

Péron illustrates the unique characteristics of small islands—spatial and societal “islandness”. Instead of using a negative word such as “insularity” to describe (small) islands, scholars use the term islandness to show the embedded character of islands in general—geographically isolated, bounded space; marginalised; physically vulnerable, yet resourceful; and including resilient inhabitants in a particular way [

4,

23,

24]. Even in governance, this character is influenced by the interaction of geography and history. Geography contributes to the character of governance, which is unique, isolating, and permitting of autarchy, stability, and endogenously driven evolution. Meanwhile, seen from the historical trajectory, small-island studies have mentioned that the typical governance on islands tends toward contact, favouring dependence, assimilation, change, and exogenously driven evolution [

25].

Island studies profile (small) islands as spaces that tend to be isolated, away from the closest mainland and the capital city, and challenged by transportation, but also as (mostly) rural spaces that are resourceful (for ecosystem services) [

26,

27]. Such rural spaces endowed with these potential natural resources eventually attract outsiders to take a role in transforming them to keep up with globalisation, economically or socio-ecologically. Based on this approach, the understanding from the outside (the centre and the periphery) about islanders is very often that the individuals there are conservative people, not wanting to change and not having the mechanisms for changing. They are staunch defenders of the past, and perhaps they do this because they (think) they do not have a future [

26]. This behaviour has (mostly) triggered tension among islanders when transformation issues arise [

28]. Island studies also believe that, even with boundedness, islanders can turn (their situation) into a positive one, as they have a great kinship among themselves. They can engage in mutual activities, and work hand in hand to succeed in their collective action goals. Such is the resourcefulness of islanders [

29].

Together with indigenous islanders, local governments seek to optimally implement participation. Participation is a fundamental aspect of contemporary planning processes. Schools of planning have shifted to become more communicative and inclusive, involving many parties in the process and its preparation, especially local populations, which are usually underrepresented in planning arenas [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. According to participation theories, the diversity of involved actors is crucial to building comprehensive and communicative planning such that the output can be accepted and implemented by all the represented actors involved. Participation is seen as an inseparable part of community capacity building. It could be considered the basis, part, or instrumental [

33,

35,

36]. Fraser [

37] argued that the more community capacity increases and is mobilised, the more organised institutional structures emerge and the more positive neighbourhood outcomes may be achieved—including, among others, influential neighbourhood governance entities that can plan and navigate the social terrain. Some literature, among others Hess [

33], McNeely [

38], Saegert [

39], Van den Broeck [

34], and Fraser [

37], mentioned that the scope of participation (similar to community capacity building) generally involves the development of various types of social capital, shared commitment among community members, the ability to solve problems and access resources, grassroots leadership, the building of consensus, and the unconditional participation of inhabitants.

The participation theory used in this study emphasises the concept of capacity building, among others conveyed by Hess [

33]. According to him, capacity building puts forward a transformation process with inhabitants identifying assets and relationships in their locale. If it develops further, it can bring about significant changes such that they can build independence from social service interventions [

33]. Substantial changes in the form of self-reliance can be economic, social, and environmental. The community building mobilised here is carried out to increase the environmental awareness of the local community and boost their economic welfare. This concept often involves mapping out resources and meeting needs by strengthening resources through local action [

33]. According to Hess, change through capacity building can be distinguished from other community practices (such as community organising or community development), as it emphasises five bases: (1) participation that leads to leadership as the primary value of the practice; (2) communal conception of public interest; (3) specialisation in agenda planning; (4) focus on internal social capital; and (5) the nature of civic engagement as an engaged citizenry (see

Table 1 below) [

33].

As capacity building wants to improve relationships and conciliation, it avoids conflict and focuses on voluntary action [

33]. The capacity-building or self-help approach “assumes that increasing the capacity of residents to address their problems will result in improvements in the quality of life and the ability of residents to help themselves in the future” ([

40], p. 14). Furthermore, community building in this paper’s context is defined as an immaterial form of development that puts forward the development and strengthening of community relations from within and outside, aiming to profoundly influence changes that become the goal of action and to resolve problems that are community-identified issues [

18,

41].

In the postmodernist era, inclusive planning, participation, and community capacity building are essential elements of planning processes. In practice, an optimal means of implementation can release the tension that might emerge in the transformation process and, in some instances, change it into a consensus phase. However, somehow, the question of whether or not consensus is really the goal must be studied. The idea of a democratic process respects differences of opinion if they are constructive. Yet, there are criticisms of the outputs of community building itself, especially those that question the real benefits that local communities can experience from the initiative [

37]. Due to the many community-building processes that donors have brought to islands, there has emerged a general tendency for local inhabitants to be dependent on outside aid [

9]. After NGO/assistance funds are depleted, there is a degradation of what the island’s inhabitants have learned in terms of preserving the environment on the islands. In addition, other criticisms address the opportunity for the misuse/transfer of government responsibility in an effort to resolve the socio-environmental issues of neighbourhoods that are imposed on the community or third parties without sufficient budget, space, nor resources for them to develop spatially and non-spatially [

37]. Thus, in order to pave the way for sustained capacity building, we dynamize it by putting it in a broader frame, embedding it in social innovation.

The research mobilises social innovation because it focuses on collective problematisation and outlines a multi-actor approach. This will eventually build a framework for innovative socio-spatial planning approaches that are linked to the governance approach [

42]. As a theory, social innovation elaborates on opposition or resistance to the existence of community exclusion that leads to conflict due to injustice regarding economic, social, and political aspects. It aims to improve society in terms of equity, inclusion, and opportunity beyond the acceleration of economic growth, productivity, and market-rational behaviour [

43,

44]. Many of the previous studies on social community have mentioned that the generator of social innovation is third sector organisations (e.g., NGOs) that help distressed/excluded communities tackle their problems of development inequalities, marginalisation, and other issues, and bring forward an applicable ‘panacea’ for transforming their condition of exclusion [

11,

21]. According to this theory, transformation in distressed communities can be realised by encouraging the emergence of initiatives to meet basic needs (livelihood, security, safety, equal access to politics), creating inclusive social relations and political empowerment, while connecting to social change at the “supra-local scales” [

45].

Social innovation focuses on the efforts of indigenous people or local inhabitants to fight the dominance of a structural system that causes their social, economic, and political marginalisation. Social innovation is used to strengthen initiatives and build a sense of equality in excluded communities. The concept of social innovation believes that agents play a role in transformation processes; resources are mobilised and disseminated in collective action through relationships between agents, institutional structures, and social systems [

46]. As such, it is essential to investigate how the sharing of knowledge, the sharing of action, and empowerment are promoted among agents within communities, and how they influence institutional frames and collective action to solve a local community’s problems and lead to alternative governance. Therefore, in practice, while community building avoids conflict to reach its goal, paradoxically, social innovation seeks to unravel the conflict and work together to find a solution from the root of the problem.

Social innovation theory leads to a deeper understanding of spatial planning’s institutional links as an institutionalist approach. Social innovation describes three significant contributions to planning techniques that move them closer to implementing participatory/inclusive planning. It contributes to a deeper understanding of spatial planning’s institutional embeddedness, focuses on collaborative problematisation and expands on the multi-actor method. It establishes the framework for a socially innovative planning strategy that can result in a bottom-linked approach to governance [

42]—a critical idea of social innovation [

21]. Bottom-linked governance is defined as a heterarchical governance model that brings together social-innovation actors and institutional enablers of social innovation, prioritising network self-organisation and solidarity-based collective action [

34,

47,

48,

49]. This governance paradigm may contribute to closing the gap created by governance bottlenecks in geographically marginalised locations such as small islands. The relationship between each stakeholder is heterarchical, resolving the problems associated with market-based governance arrangements by strengthening the formation of solidarity-based governance; the necessary scaling up of policy, spatial and aspatial support; and rights for socially innovative actors and externalised communities [

50].

Many institutionalist academics are conducting an increasing amount of research that addresses social, economic, and environmental issues. This research refers to how the interactions of actors and institutions on small islands result in different transformations, subsistence outcomes for indigenous peoples, and new orders, including existing policies, access to government programs, subsistence strategies, and patronage of local systems. Therefore, this research highlights the small-island transformation process, emerging tensions, and how actors make efforts to overcome problems that arise with and within the local community.

Finally, this study underlines the (political) bargaining power of externalised individuals or communities. The concept of bargaining power has long been used in the fields of law, economy, and social science [

51,

52,

53]. It is used in this context to see the extent to which certain stakeholders can participate in decision making and have input in polic making that has an impact to the benefit of environmental conservation. Here, bargaining power means the relative ability of parties in an argumentative situation (such as policy making) to exert influence over other parties [

52,

53]. According to this concept, actors with greater bargaining power are likely to obtain more favourable terms in negotiation, and they need a relative ability to win the argumentative situation. The concept of bargaining power believes that bargainers must have the capability to change ‘the bargaining-set’ [

54] to influence the outcome of a negotiation and, ultimately, win [

54]. For those purposes, bargainers must have something to offer, access to knowledge/skill/information, and specific knowledge of the particular problems to be solved [

54]. Through capacity building and social innovation, indigenous islanders have tried to build not only their self-reliance but also the confidence to voice their rights in development towards a more environmentally friendly policy for their island. The bargaining power of the usually disadvantaged party (island’s inhabitants) in policymaking also emerged as a result of the community-building process and increasing knowledge value that enables them to negotiate with the upper-scale government and networks to be more ecologically concerned with the sustainability of small islands.

4. Results

4.1. Participation of Local Actors in Community Capacity Building and Enabling Empowerment Mechanisms

Around 1995, training was conducted by several educational institutions on the mainland, namely, Bandar Lampung. This involved sharing knowledge related to agriculture and fisheries with the people of Pahawang Island. However, these activities were not sustainable. The training lasted only a few days, after which the interaction with the residents ceased. However, the community still gained initial knowledge about agriculture and fisheries through the training. Previously, they relied on traditional knowledge to conduct agriculture and fisheries. Then came the local conservation NGO Mitra Bentala (MB), which committed to building the local community society’s capacity on the small islands of Lampung Bay. The first small-island project was on Pahawang Island. MB wanted to create an integrated, sustainable, and community-based small-island development model that could become a pilot for other small islands, particularly in Lampung Bay.

MB is a distinguished environmentally concerned NGO in Lampung Province. It is a pioneer in Lampung that focuses on environmental issues, explicitly highlighting small islands. In its work, MB helps local communities to share knowledge, act, and boost their bargaining position in fighting for their living conditions to improve and be more sustainable in terms of the environment and related aspects—economy, culture, and politics. It has knowledge about and is networked with technology, government, and media, which can help build local capacities and foster cooperation and dialogue in conserving the environment and preventing environmental damage. MB initiated and echoed the discourse on mangrove conservation and the negative impact of converting it into shrimp ponds or destroying it for other reasons. In addition, it vigorously echoed the discourse through access to technology and mass media networks, both local and national, as well as both mass and virtual media (online news and social media).

In 1995–1997, young people who were members of MB came to Pahawang Island for the first time. The village government (headed by a customary leader) warmly welcomed the good intentions of the youth to help the Pahawang community increase its knowledge about maintaining the ecosystem. Little was done because of limited funds, but the MB members were committed to visiting the island and sharing knowledge with the people there. In the early days, when MB conducted initial surveys on Pahawang Island, they took the initiative to share with indigenous islanders know how of nature conservation on small islands to maintain mangrove forests and coral reefs with the limited funds they had. They approached the village government and community leaders there and were well-received. By cooperating with traditional leaders and local public figures/elders, they sought to gain the trust and welcome of the inhabitants. This informal approach had been carried out since 1995, before they received sponsorship funds.

In the 2000s, MB received funding from international donors to carry out capacity building on small islands using the participatory rural appraisal (PRA) method. The MB began a guerrilla campaign for the island’s intended mission—to establish an integrated, sustainable, and community-based small-island development model in Lampung Province, beginning with Pahawang Island. Having previously established good communication with a customary leader and local public figures, the NGO obtained support in interacting with and guiding the island communities. With straightforward advice from conventional leaders and respected figures there (such as religious leaders, wise elderlies, and vocal youths), the community was willing to participate in capacity building initiated by MB. The absence of a single central figure allowed MB to coordinate with these figures before deploying themselves directly to training the community in general. In the PRA process, the results cannot be seen in the short term; rather, they must be carried out continuously over a long period. Therefore, with international sponsorship, MB organised the PRA process ethnographically (becoming part of the community)—living together and interacting intensely on the island.

MB started the community practice by mapping the problems and potential of natural resources in Pahawang. In the 2000s, it gathered all the representatives of the hamlets there. The mapping was attended by village officials and community representatives from six existing hamlets (generally, men who were breadwinners). For three to four days, discussions were conducted to identify issues faced by Pahawang. Upon identifying the various problems that the island encountered, MB initially focused on coaching the inhabitants to fish in an environmentally friendly way and then expanded to issues of gender, organic farming, and animal husbandry. The MB team continued to approach the Pahawang community to change the way inhabitants unconsciously destroyed the environment for a living and started to build a sense of belonging to their environment. Knowledge sharing with islanders was continuously carried out with regard to maintaining the island’s coastal environment, mangrove forests, and coral reefs.

In engaging in the community building practice, MB collaborated with its networks—both domestic and foreign allies—with expertise according to the field on which they were focusing. At least 24 foundations/institutions participated in the community building. Apart from domestic networks, international organisations such as Wetlands International, VSO Philippines and Thailand, APEX Japan, UNDP, and Heifer International became interested in implementing projects in Pahawang that aligned with their ongoing focus areas (for example, land use mapping, gardening/cultivation, mangrove and coral reef conservation, and fish aggregation devices/FADs). From 1998 to 2014, Pahawang inhabitants participated in training, workshops, and knowledge sharing from these networks. Though the MB project with donors was completed in 2010, communication continues and invitations for enhancing Pahawang inhabitants’ skills are always offered. Every invitation from MB and its networks is warmly welcomed by representatives of the Pahawang community. The sharing of knowledge and actions carried out by MB and the Pahawang residents has gradually increased their capacity to engage in concrete environmental steps, agriculture in harmony with nature, the ecological management of natural resources, and business development through community assistance in making fish aggregation devices (FADs), cages, and plant cultivation, as well as their being introduced to the advantages and disadvantages of the shrimp-farming business. In addition, those allies have been fostering and strengthening local organisations, rehabilitating, and maintaining mangrove forests, involving the community in groundwater conservation through the creation of biopore infiltration holes, involving the community in making maps of capture areas, and increasing children’s capacity and concern for the environment and surrounding life through the school curriculum. In addition, the people of Pahawang carried out many other programs with MB and its networks to strengthen value added in the form of knowledge that is more in-line with the environment and more sustainable for their livelihoods.

When the inhabitants gradually switched to environmentally friendly activities and became more concerned about the environment, a discourse arose regarding how the environment is maintained. People could also improve their economy. MB initiated local inhabitants’ introduction to a husbandry program as an alternative economy. Each family in each hamlet received three goats, and the residents were trained to raise livestock. Through its allies, MB brought livestock experts from a well-known provincial university nearby (University of Lampung) and from organisations abroad (from Japan and Korea) to Pahawang to conduct training in line with its rural development agenda. Almost 700 goats were distributed to each hamlet at that time, but only the Kalangan hamlet showed results. In general, the obstacle was the difficulty involved in providing livestock fodder. Still, somehow, in the Kalangan hamlet, husbandry remains a practice, while other hamlets have not continued in the livestock business.

MB played a pivotal role in introducing Pahawang residents to a network of polic makers, academics, and environmental experts to learn, engage in dialogue, discuss, and exchange ideas. These practices gradually activated the residents’ self-esteem. They became confident in expressing their concerns about the environment and the issues they have faced so far to policymakers at upper-scale levels. One of the activities that represent the above was the involvement of Pahawang residents in the Lampung coastal management project agenda (2000), which became the stepping stone that strengthened their bargaining position regarding policymakers at multiple scales (regional and province). Stemming from this involvement, local Pahawang agents began speaking out in various training sessions, seminars, and hearings at the district, provincial, and national levels, through the network introduced by MB.

Then, around 2007, the ecotourism discourse emerged in Pahawang. After the emergence of a sense of belonging and a sense of environmental crisis among indigenous islanders, MB initiated a discourse to create another economic alternative on the island—tourism development. The target was to improve the community’s economy through environmental conservation. Residents would serve as business actors in the tourism sector with the knowledge they gained from mentoring and workshops with MB’s networks.

4.2. Disclosing the Island Community’s Fishing Practises: The Emerging Conflict and the Proposed Solution

As mentioned before, MB used a PRA approach in community capacity building—mapping the locals’ problems by initiating an open dialogue with residents and holding discussion forums at night. Furthermore, infiltration through religious agendas was effectively carried out. MB participated in the regular recitations/pengajian of residents, as islanders who are predominantly Muslim often have a recitation agenda that serves as a place to gather and exchange ideas not only on religious matters but also on other matters. This yielded good results, because it included a variety of residents who took part in the event. Initially, a few of the residents hesitated to follow all of MB’s capacity-building practices, giving the excuse that they had to take advantage of the available time to rest after engaging in fishing or farming. Residents became willing to open up to MB and its networks after being persuaded by the traditional leader and respected elders. They discussed and shared experiences and expertise.

In the process, not all residents could receive the training and shared knowledge that MB provided in terms of capacity building, related primarily to the way they caught fish and were using tools that harmed the surrounding environment. This was also associated with the conservation of coral reefs and mangroves. Tension emerged when the residents did not want to change their ecologically harmful habits. Resistant residents felt that their incomes would drastically drop if they could not use trawls, potassium, or bombs that produced relatively large amounts of fish in a short period. The persistence of their conflicting ideas was shown by their infrequent participation in the discussion activities (with MB or the village government). Those who made a living through activities classified as damaging the environment (in mangrove forests, fish habitats, and the like, as well as coral reefs) believed that the way they worked would significantly impact their income, and they did not want this. Their principle was that as long as their practices did not directly harm other people, what they did was a normal thing, carried out for the sake of supporting their families.

To better understand this resistance, MB carried out an intensive community capacity-building process through a door-to-door or individual approach when the local people were not fishing. MB provided counselling and guidance on fishing without destroying the habitat and provided information about why protecting the environment was essential on the small island. Every conflict of opinion was resolved through dialogue, both in group discussions and through a personal approach (door to door). Members of MB attempted to confront the resisters’ minds, not their morals or mentality, in a gradual and digestible manner in order to ensure effective delivery of the discourse. Then they levelled up the narrative into finding alternative ways to enhance the economy aside from fishing and agriculture, while maintaining an environmentally friendly way of life on the small island.

MB attempted to ensure that the knowledge and the know how they provided and shared with the islanders, particularly the resisters, could be effectively transmitted. This could be accomplished through fostering an emotional connection with local individuals. The latter had already developed a sense of familiarity and proximity with MB members. Members of the MB had visited and stayed at the houses of Pahawang inhabitants on multiple occasions and are regarded as family, not as transient visitors. According to interviewees, the Pahawang residents consider the MB team to be a part of their community, and they do not hesitate to say that Pahawang’s success until the present cannot be separated from MB’s role in making them aware of protecting the environment without making them feel judged for their wrongdoings. From the history of MB members, it became clear that their approach to resisters (the majority of whom were breadwinners) consisted of night-time chats while smoking or sipping coffee.

The personal approach to resisters was carried out intensely and without offensive persuasion so that the resisters did not feel cornered in the dialogue but rather felt that their opinions were valued. The closure was deemed sufficient after many opposing residents with leadership potential were trusted to assume crucial positions in prominent local organizations formed to serve as the spearhead of environmental conservation. This form of involvement triggered those who initially had opposing ideas to become productive agents of change. They are not objects, but transformants who play a pivotal role in developing and maintaining the island’s environment for the better.

Gradually, fishing activities that destroyed marine habitats were abandoned. Most of the population tried to fish in an environmentally friendly way—not using bombs, trawling, or potassium. Those who still destroyed the environment, by fishing or exploiting mangrove forests and coral reefs, received social sanctions (direct warnings from the community, community leaders, and traditional leaders). Indeed, these sanctions were not written directly in village regulations but ultimately became a spirit among the island inhabitants to implement a better, more sustainable life, both socio-environmentally and economically. Sanctions promoted shame and social responsibility in each local community when a resident insisted on doing things contrary to most inhabitants’ beliefs.

Consensus regarding the cessation of environmental-destruction activities was not instant, but it was well-internalised among the grassroot Pahawang community. This awareness arose in line with the ongoing capacity building in which residents were engaging, along with MB and its allies. Trust in outside parties also increased among the residents. They appreciated those outsiders who wanted to conduct training or research to share their knowledge and experiences with the local community. One informant even claimed that an extreme way of seeing this is that, today, the islanders have more trust in outsiders who convey something than they do in the local government, which is considered to be on the same level as the inhabitants in terms of knowledge/education.

4.3. Enhancing the Island’s Inhabitants’ (Political) Bargaining Power by Means of a Local Mangrove Conservation Organisation

To maintain mangrove areas and coral reefs on Pahawang Island, MB and local communities agreed that a particular agent would be tasked with monitoring conservation activities and their cultivation. This specific agency was designed with a management run entirely by the local community. At the same time, MB would be the facilitator and advisor, informing and strengthening the village’s regional institutions. Thus, the community could actively preserve the environment and also had bargaining power through the formal forum to voice their ideas and input for better-grounded policies. The agency, entitled the Regional Mangrove Conservation Management Board/Badan Pengelola Daerah Perlindungan Mangrove (BPDPM), was formally formed in 2006. It was the initiative of both agents (MB and the Pahawang community) to create a formal body that, under the law, had (political) bargaining power in carrying out its duties—maintaining the existence of mangroves.

In determining the management, MB carried out a community consultation. Individuals who participated actively in this conversation were judged to be particularly vocal about environmental conservation on Pahawang Island. To share knowledge and action with them precisely, MB and its network were actively engaged in providing technical help and capacity building. The individuals targeted were residents of Pahawang who indulged in environmentally irresponsible fishing techniques despite previous advisories about their fishing activities that threaten the sea habitat. Over time, their awareness grew through their participation in discussions and their sharing of knowledge and action with MB. In the end, those who were initially against the idea of environmental conservation became human agents at the front lines of ecological protection. At that time, together with the village government, which supported the agency’s formation, local agents ready to join the agency were gathered—local public figures, respected elderlies, and the village government.

When this agency’s initiative surfaced and was still a hot topic of discussion among local communities, the provincial government was planning an agenda for coordination with all the agencies under it. Having a strong network in the district and provincial governments, MB persuaded the provincial government to hold one of these agendas on Pahawang Island to show the beauty of the island and its potential, not yet known to the public. As a result, in 2009, a provincial government meeting was held on Pahawang Island, attended by the then governor (2009), Sjachroedin, along with other high-ranking officials in the provincial- and district-scale offices under him. That marked the first time Pahawang Island had been visited by many local governments—the provincial government and related agencies. On the agenda, local community representatives and MB included requests for support to establish a local mangrove conservation organisation.

By introducing the potential beauty of Pahawang Island, the provincial government at that time believed that the originality of Pahawang’s beauty could benefit the region and become the next big thing owned by Lampung Province, especially related to its potential to become a new tourist destination. From there, the discourse about Pahawang and island tourism came to the fore. With direct support from the governor at the time, the direction for allocating the infrastructure budget, public facilities, and training was aimed at Pahawang Island. The directives were handed down to the relevant agencies of the Lampung-province and Pesawaran-district levels. Another significant impact of the meeting was the direction to support the establishment of a local environmental conservation institution proposed by the Pahawang residents and MB.

In its development, after obtaining an assurance of legality from the district government level, in 2009, the island’s community and MB (sponsored by UNDP) encouraged the Pahawang village government to issue a regulation related to mangrove conservation, namely, the Mangrove Protection Area Regulation. The law regulates the zoning of mangrove forests into core zones, buffer zones, and utilisation zones. In addition, it contains obligations and indicates unallowed activities related to the mangrove forest, as well as sanctions for violators. BPDPM was formed to enforce these rules. Furthermore, capacity building aimed at empowering the island’s inhabitants continued. This can be seen in the numerous pieces of training (both prior to and following the official establishment of BPDPM) that involved local communities as BPDPM members. This boost in community capacity is evidenced by the community’s increasing knowledge, skills, and attitudes in environmental conservation, which are improving. The Pahawang community has supported and recognised the mangrove forest as a protected area under the management of BPDPM.

As mentioned before, the Pesawaran District Government approved the establishment of BPDPM (2009). At that time, the Pesawaran District Government did not have regional regulations specifically regarding mangrove management in its area. As a newly expanded district (2007), Pesawaran lacked a mangrove management strategy, which was initially developed by MB along with Pahawang community representatives. To transform Pahawang Island into a model for the integrated, sustainable, and community-based development of small islands, the Pesawaran district government endorsed MB’s plan by establishing statutory policies to encourage the creation of local mangrove conservation organisations. This was the first step of the district to support environmental conservation on the small island. Based on the regulatory documents we obtained, there are several policies related to mangrove management, namely, the Pesawaran Regent Decree No. 162.B/III.06/HK/2009 concerning the Mangrove Protection Area Management Agency (BPDPM); Pesawaran Regent Decree No. 175/III.06/HK/2009 concerning the Mangrove Working Group; and Pesawaran District Regulation No. 4 of 2012 concerning the Spatial plan’s policy/Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah (RTRW) of Pesawaran District in 2011–2031. In those implementations, the regulations were related not only to mangrove management but also to the management of shrimp ponds. The policy also contains licensing for shrimp ponds and forming a pond monitoring and evaluation team. In practice, unfortunately, these policies were more supportive of the intensification of shrimp ponds than of mangrove conservation.

However, it was noted that 2012 was the heyday of BPDPM, as the agency was able to take on an optimal role in monitoring environmental conservation, especially mangroves and coral reefs on Pahawang Island. The sense of belonging among the administrators and their members concerning ecological sustainability on the island became the initial foundation for creating sustainable development there. The village government, which is also part of the agency’s management, supported every direction, plan, and activity of BPDPM. In addition, with the formal ratification of the agency, BPDPM has a strategic position in voicing its opinions and ideas, which plays a role in creating other policies related to the protection of mangroves and coral reefs that are part of the coastal border. This impacts the collaboration and communication between BPDPM and the village government in building and maintaining a shared commitment to ecological conservation.

4.4. Implementing Community-Based Ecotourism (CBE) Discourse Utilising the Bottom-Linked Governance Arrangement

The Pahawang inhabitants have experienced significant changes, from their ignorance of good environmental care on their small island to the point that they knew they must change their behaviour to be more environmentally friendly and add value to the island they inhabit. As a result, the discourse on ecotourism development has come to the fore, against the background of improving environmental conditions, thereby increasing public awareness of carrying out economic activities from an ecological perspective. Conservation monitoring began to run through the local-community conservation agency, BPDPM, which was integrated with the village government as a protector and part of its management in 2010.

Given their readiness to engage in environmental awareness, representatives of the Pahawang community, assisted by MB, began to promote their island as a new ecotourism destination in Sumatra. To obtain support for facilities, infrastructure, and supporting policies, representatives of the Pahawang community, BPDPM and MB fought in the political realm with the candidates for regional leaders at that time by carrying out an environmentally friendly development mission and promoting the island’s great potential in the tourism sector, which would benefit not only the local community but also the regional/local government.

In 2010, the provincial government supported this aspiration to establish ecotourism on Pahawang Island. It directed the institutions/agencies under it to provide support in terms of facilities and infrastructure to realise the ecotourism discourse voiced by the community and MB. Since then, some help (financial, infrastructure, training) has been provided to the people of Pahawang Island from the government side. This included: the construction by the Public Works Department of a paved block road track along Pahawang Island, which can be used for mountain bike tourism destinations; stimulant assistance for self-help housing from the Settlement and Public Housing Service Department; a centralised solar power plant for 100 houses and 342 units of a solar home system (SHS) from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries and the Mining and Energy Office of Pesawaran District; social assistance for low-income families from the Ministry of Social Affairs; training on coral-reef transplantation and foods/beverages made from mangroves as well as foods made from seaweed (especially for women); construction of the Ornament Mosque Lampung by the Social Bureau of the Lampung Provincial Government; support with three boats from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries; the distillation of seawater into fresh water from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries; and electricity assistance from the state company, PLN. This help runs alongside the plans and preparations for Pahawang to become an ecotourism destination. From 2010 to 2017, Pahawang was the only small island receiving significant attention from the government of Lampung Province and Pesawaran District.

To finalise the planning for the opening of community-based ecotourism (CBE) on Pahawang Island, the local community followed the directions and capacity building from MB. At that time (2010), MB planned to encourage ecotourism and education tourism (edu-tourism) with a community-based concept in which the main actors in the ecotourism business are the local inhabitants. The tourism concept is environmentally friendly, with target visitors, namely, families, corporations/organisations, students, researchers, and individuals. The ecotourism offered to visitors is mangrove tourism, in which a local guide introduces the mangrove forest and visitors are asked to contribute to the planting of mangrove seedlings that are included in a tour package. Afterwards, they can enjoy the underwater scenery through snorkelling activities or other family rides. Women are also empowered in the tourism business by managing homestays and providing traditional cuisine for visitors, both overnight and on one-way trips. In the children’s education sector, the school curriculum for kindergarten and elementary and junior high schools on the island of Pahawang includes environmental care (especially mangrove forests and coral reefs), ecotourism, essential tour guides, and several regional dance activities that will ultimately be attractions for overseas tourists (especially government agencies, domestic and foreign corporations/organisations) when necessary. With all the provisions from the local community, in 2010 Pahawang Island was opened as an ecotourism and edu-tourism destination and received a warm welcome from domestic visitors.

Following the development of tourism in Pahawang, which has begun to attract many visitors, assistance and cooperation were offered by private and state-owned companies in the form of corporate social responsibility (CSR). A large number of aid funds, facilities, and infrastructure elements that sporadically came to Pahawang triggered euphoria among islanders. However, they found it difficult to determine their attitude regarding which assistance or facilities supported eco-tourism as well as environmental conservation and which were, conversely, damaging to the environment or marine habitats. When MB finished its community capacity-building program with its donor institutions, it was time for the community to independently decide what was best for its survival, given all the transformations that had taken place over the last few decades.

The transformation of Pahawang Island into a tourist destination has been taking place since 2010. Although there has been a shift in tourism development, this small island is never empty of visitors. The shifting referred to here is the spirit of ecotourism and edu-tourism, which first fuelled tourism development there but unfortunately later morphed into mass tourism. Individuals in the community who have directly benefited from the existence of this tourism (generally in the hamlets that hold tourist sites and facilities) seek to maximise the profits they can obtain until they cross the boundaries of the conservation commitment that they firmly hold as a previously set tourism goal. Instead of being sustainable from an environmental point of view, more real environmental degradation is occurring on Pahawang Island. Apart from the monitoring role of defunct local institutions, a few residents with greater capital and business connections have acted as “small kings” in the Pahawang community—those who are successful in the tourism business on the small island and take the initiative to expand their business to improve the economy of individuals and small groups.

If all members of the Pahawang community adhere to their long-term commitment established at the beginning, this small island can transform into a sustainable environment and experience an increase in income through economic alternatives in the ecotourism sector. In addition, long-term collaboration regarding environmentally friendly governance is sought between every stakeholder involved (from indigenous groups such as local business actors, the government and policymakers; to private parties such as investors, donors, and business partners; with NGOs and academics as a supporting system), especially in strengthening community institutions.

Unfortunately, over time, when MB finished its programs and thought that the Pahawang community was independently managing the environment and community-based ecotourism, the spirit of sustainability began to degrade in each local community that had once been committed to these achievements. During its development, the majority of Pahawang people involved in tourism began to act independently, focusing exclusively on increasing their income. Mutual assistance (gotong royong) and community agendas are rarely implemented, despite invitations. Each of them is now focused on growing the network of outside island travel agents (such as from Bandar Lampung City, Jakarta, or other big cities) with whom they collaborate. Those who are independent travel agents with strong promotional capabilities can attract a large number of visitors by offering affordable tour packages. In this case, the community acts as a provider of lodging, food, and transportation for visitors, with profit-sharing determined by the outside travel partner. This condition persists to the present day.

5. Discussion

This paper emphasises the way capacity building of the island’s community was ‘dynamized’ by becoming part of a process of social innovation and bottom-linked collaboration and governance, sustainable empowerment and building political bargaining power. It focuses on the grassroots efforts of the island’s inhabitants who had the will and ability to create a sustainable environment on their island until they reached a point where they could instil a sense of urgency about the critical nature of their mangrove forests, coral reefs, and underwater habitats. It shows how the islanders created a legal formal local institution (as one of the bargaining power vehicles) to support them in the face of policy to protect the island’s environment. The islanders could voice their aspirations and even carry out a crosscutting dialogue with policymakers (with the help of networks from MB) to boost attention for their island and its potential and provide material development (road infrastructure, health facilities, education, etc.), training (related to economics, social culture and ecology, teaching literacy, entrepreneurship workshops, etc.), societal transformations (organisational, legal, economic, cultural, financial) and bottom-linked networking. The islanders had the opportunity to dialogue with the then vice president, introducing their island to ministries, the domestic public, academics/international visitors, and other related parties.

5.1. The Small Island‘s Transformation through Practices of Enhanced Capacity Building

Referring to the capacity-building concept delivered by Hess [

33] and brought into dialogue with the social-innovation concept, we observe that the transformation process on Pahawang impacted an increasing number of actors involved, as well as the form of institutions and governance arrangements. Capacity building that emphasises five bases, based on Hess [

33], dynamized with the three-dimensional goal of social innovation [

21] led to the emergence of (political) bargaining power in the process, toward a bottom-linked governance arrangement. We find that the NGO MB, as an early social innovator, carried out a community-development process for nearly two decades, emphasising the primary value of the participation of indigenous islanders as agents of change. The NGO built public awareness of the environment by taking advantage of the regular schedule of community gatherings and holding meetings in the islanders’ spare time to engage in continuous dialogue with community representatives. The goal was to instil not only knowledge values but also leadership values and determine who could be local leaders, influencing citizens from within to make breakthroughs and build community initiatives to be more responsible for their surroundings rather than prioritising their egocentrism. The process of capacity building has changed the ignorance of citizens into the form of understanding the value of ecological awareness, building a sense of belonging and a sense of crisis in terms of environmental governance for mangrove and coral-reef conservation.

Although the basic concept is capacity building to avoid conflict and emphasise voluntary action (communal interest), in practice, MB did not avoid conflict. Rather, it tried to solve it together with influential citizens. A door-to-door dialogue was held to convince islanders of the importance of MB’s plan, what the NGO was doing, and why the community should be concerned about ecological preservation and stop the practice of ecologically destructive fishing. MB also saw the leadership potential of the perpetrators of environmental destruction through their fishing activities—their critical thinking, knowledge, and motivation to meet essential needs. Therefore, MB continuously sought to improve their understanding and involve them in workshops and seminars outside the island as representatives of the people of Pahawang, thereby letting them learn from the other participants and the activities themselves. Moreover, MB opened the door for them to network with other parties, who would be useful for them in the future.

The capacity building showed on the island mobilised agenda planning as a power basis. Similar to what Hess ([

31], p. 21) says, the NGO started by “focusing on participants’ (re)discovery of local assets, new relations and opportunities[;] participants in community building develop a new vision for their community, one that external actors would not have been able to discover without them”. From that finding, together with the islanders, MB engaged in follow-up activities to solve problems and utilise their potential for their communal and sustainable benefit. However, Pahawang’s emphasis on capacity building differs from Hess’ view that capacity building generally prioritizes internal social capital over collaborative or bridging capital in terms of social capital. The community capacity-building initiative spearheaded by MB on Pahawang Island incorporated not only internal social-capital empowerment (e.g., discussion among residents, internal mutual assistance, and dialogue-based solutions), but also collaborative relationships with external agents via its networks, and material, knowledge-related, economic, political, cultural, governance, etc., transformations. One form of building collaborative social capital was to involve Pahawang representatives in the agenda of making strategic plans initiated by academics and local governments related to coastal management and making Pahawang a host of one of these activities. Further, because capacity building proved to empower the internal social capital and communal interest, it also had the goal of engaging the typical citizen. We argue that the dynamics of the capacity building faced during participation in the study area show the importance of a structural approach to local communities, first embracing the village government, local public figures, and elderlies to obtain support for the community-building program. This method is one of the prerequisites for starting the involvement of new local actors [

33,

61]. In the early years of capacity-building practice, when the village government and community leaders in Pahawang actively spoke out and supported the initiated changes, Pahawang island’s residents gradually participated in it, regardless of their initial motivation (mainly because of their reluctance and respect for their leader and elderlies). This made the process of sharing knowledge and action easier to implement. However, an approach through these figures is insufficient to overcome the emergence of conflicts among citizens who reject change. As is evidenced (at least) in Pahawang, this requires extensive interactions and a considerable period of time to integrate, fostering a strong bond between the people of Pahawang and MB. With this method, the residents of Pahawang Island could approve or reach an amicable agreement regarding the programmes proposed by MB, such as capacity-building objectives in building initiatives among themselves—the population of Pahawang Island.

5.2. Capacity Building Embedded in Social Innovation: Evidence in the Trajectory of a Small Island’s Transformation

In line with Moulaert [

63], who believes that great changes can start in the neighbourhood—the small unit of a city—this article also considers that the rural neighbourhood on a small island to be heterogeneous, yet palpably localized, especially in Indonesia, which is an archipelagic country. The rural neighbourhood is a prominent site for initiating and implementing social changes that may become a model and ripple through other small islands around it or throughout Indonesia. The transformation on Pahawang Island can also be seen as an “experimental innovation”—the term used by Moulaert et al. ([

63], p. 5)—that triggered the emancipatory process. Based on the description in the study area profile and findings related to conditions, dynamics, and what MB carried out together with the islanders, it can be seen that several factors are prerequisites that can lead to and raise grassroots initiatives to the upper scale. The capacity-building process initiated by MB was practically enhancing the dynamic nature of its practice. When examined through the lens of social innovation, the actions conducted were compatible with the three-dimensional goals that underpin social innovation. In addition, this paves the way for empowering endeavours and sustaining the process, which will ultimately result in a more collaborative governance structure incorporating multi-scale actors. The following is a detailed explanation of the three-dimensional idea of social innovation discussed above.

Initiative in satisfying basic needs. Related to the idea of fulfilling basic needs, socially innovative agents (MB) carried out the community capacity-building practice by initiating alternative efforts to improve the economy of local communities and thereby improve their standard of living, allowing them to slowly escape poverty. This was performed through educational programs and workshops involving other agents of change (NGOs, academics, international foundations/donors). Some of these educational activities included training on how to farm in harmony with nature, starting a livestock business, breeding fish with floating nets, introducing shrimp farming (advantages and disadvantages), and community-based ecotourism. The capacity-building process awakened residents’ awareness of social, economic, ecological, and governance aspects that could increase their wellbeing—sharing knowledge and sharing action to find alternative ways for residents to be resilient on the geographically isolated small island. Island’s inhabitants were involved in reaping the benefits of, and being educated in, environmental preservation, which indeed was a pivotal aspect in the small island context. In line with the increase in people’s knowledge, the local (potential) leaders began to invite other residents to act together through a new forum—new social-innovation agents on the local scale (BPDPM, tourism awareness local group/Kelompok Sadar Wisata (Pokdarwis), women’s community, small and medium business cooperative/Koperasi)—that made changes by sharing knowledge and actions to manage local livelihoods and mangrove forests, make handicrafts and food products from mangroves, and conserve coral reefs and marine habitats, which are the natural wealth of the island.

Initiative in social transformation. This social transformation is salient through the development of new social and institutional forms, including a process of strengthening collaboration between individuals and social groups [

43]. The indigenous islanders who initially met their daily needs independently began to build collaborations, as seen from the shared actions to build educational and worship facilities, road infrastructure, electricity, and lighting. From the economic side, cooperation emerged such that inhabitants living on the island’s coast collaborated with those geographically untouched by tourism to take part in the tourism business (by selling local meals for tourists, managing homestays, selling souvenirs, and providing sea transportation services). MB further triggered an embryonic transformation involving women in the economic sector. In the past, women stayed at home, managing household affairs, while men engaged in farming or fishing. Now the role of women has shifted—they have become more productive by being involved in the economic sector (e.g., managing homestays or cottages, preparing meals for tourists, producing local food that can be used as tourist souvenirs). MB and its network targeted capacity building not only for men but also for women, so that they would have the initiative and enthusiasm to make changes. Those who had a leadership spirit were triggered to initiate and ‘influence’ other women to learn and make headway together. Aside from the intertwined economic perspective, social transformation is seen in the increasing collective awareness of the environment, incorporating knowledge of ecological conservation through social and political empowerment, gaining the power to act, and building networks horizontally and vertically to the upper-scale level of policymakers.

Initiative in political transformation. The political transformation process that the Pahawang people are going through reached its defining moment when they participated in a ‘political agenda’ which correlated with their position as some of the inhabitants of the coastal area—collaborating with various policymakers at the provincial and district levels and with other vocal actors from third parties (NGOs, communities, academics) in 2000. The agenda was to formulate a Strategic Plan for the Management of Coastal Areas of Lampung Province, which was initiated by academics with international funding support. After the island’s inhabitants obtained the knowledge and developed their self-esteem, they were introduced to and involved in new forums outside the island. They used that forum to express their actual needs in coastal governance, particularly small-island governance, in order to ensure that the strategic planning that was co-created was focused on environmental sustainability and the benefit of the local population in particular. The meeting was a watershed moment when, slowly, the pipeline of ideas and networks opened for representatives of the Pahawang community, allowing them to start voicing their aspirations among higher-level policymakers to fight for their welfare as indigenous islanders on a small island, who needed pro-environment development policies to achieve a long-term sustainable livelihood, breaking the chain of inequality that they had experienced to date. By leveraging their available resources and the support from the network they had built, the Pahawang people used political momentum not only to obtain funding assistance for ecotourism-based island development but also to confirm their spatial existence in the midst of incessant mainland development, which was considered more influential economically. From the macroscopic view, this process of political transformation levelled up the narrative of MB and Pahawang’s inhabitants as local agents, not only for internal strengthening but for strengthening their position in development at the upper level of policymaking.

5.3. Political Transformation from an Enhanced Capacity Building Led to the Emergence of the Local Community’s (Political) Bargaining Power

The political transformation affected the emergence of (political) bargaining power, especially in policymaking. The shift that empowered the community in terms of knowledge and experience internally did not rule out the possibility of spreading its wings to engage externally, particularly in policymaking, as the next step. As this social innovator (MB) believed that empowering distressed communities at the grassroots level was not enough, somehow it had to encourage the next stage—involvement in policymaking at the upper level. This is where the concept of (political) bargaining power and one of the dimensions of social innovation (political transformation) reveal the small island’s transformation. With the experience of involvement in advocacy and speaking out in multiagent forums in policymaking, the representatives of the Pahawang community whom MB fostered, and its network, built their capital to influence and win negotiations with policymakers at the upper-scale level. This confirms Coff’s statement [

54], that by preparing the indigenous Pahawang community with knowledge value, information, and local skills, they had the courage to bargain with the government for a better policy to support them in development—that is, more ecologically concerned with sustainability on a small island. The Pahawang inhabitants offered local, regional, and even national economic contributions through the development of ecotourism in line with environmental conservation on the small island of Pahawang—the way a small developing island can bring benefits to its upper-scale region and decrease the poverty there. For this reason, the Pahawang inhabitants’ representatives asked for policy and infrastructure support from the government to promote environmentally friendly development for the small island(s). The inhabitants voiced this not only to the district or provincial government but also to a higher level. They had the chance to communicate with Vice President Megawati in the 2000s and ultimately produced recommendations to the governments below (provincial and district) to support environmentally friendly development policies for small islands in general and the island of Pahawang in particular. One concrete example of the follow up of their political bargaining power in negotiating with policymakers was the issuance of the Pesawaran Regent’s Decree No. 162.B/III.06/HK/2009 concerning the Mangrove Protection Area Management Agency, Punduh Pedada District, Pesawaran District and Pesawaran Regent’s Decree No. 175/III.06/HK/2009 concerning the Pesawaran District Mangrove Working Group. These policies provided new life for grassroots movements to engage in environmental conservation with the support of formal rules from the upper-scale level of policymakers.

5.4. Enhanced Capacity Building Embedded in Social-Innovation-Supported Bottom-Linked Environmental Governance on the Small Island

Pahawang Island underwent transformation not only in social, economic, and environmental terms but also in terms of governance. A key concept of social innovation is the emergence of bottom-linked governance [

21], which is a heterarchical model combining social-innovation actors and institutional drivers of social innovation, promoting self-organisation in networks and collective action based on solidarity [

34,

47,

48,

64]. The transformation that occurred on the small island of Pahawang indicates a change in governance towards a more bottom-linked direction. After activating the self-esteem of the indigenous islanders and equipping them with knowledge and practices related to environmental conservation, MB introduced them to a network of policymakers with the mission of obtaining support for their initiatives in areas that had not been touched by government programs/policies at any policy level. The social innovator brought local-community representatives every time there was a meeting (hearings, audiences, workshops, etc.) to express their aspirations and obtain direct attention from the government, which did not know much about the problems they faced.

“Until we bring them (Pahawang inhabitants’ representative) to Jakarta (the nation’s capital) for a hearing, we have often invited them to local governments from the district, provincial, to central levels. So that the island of Pahawang is known because we have to go hand in hand, MB could not do it alone (run everything without help). The local government also doesn’t know about the problems on Pahawang Island, (we make) the people tell their own stories (directly). Sometimes we took them to the council (Regional parliaments) to motivate the community so that they are confident (and realise) that not only MB who want to help them but many parties who want to do good things on Pahawang Island. So that’s our motivation. At that time, Megawati—when she was a vice president of Indonesia, had an audience/hearing included in the exhibition on Indonesia’s natural resources, where MB was invited as a representative of Lampung Province. So, we took the chance to directly invite fishers from Pahawang to also meet her. Not only mentoring but also events that invited us (MB), we invite them as well (Pahawang inhabitant’s representatives), even (guiding in) drafting village regulations”

MB formed an inclusive type of governance to empower the Pahawang community. Together with the local community and their alliances, they mobilised solidarity-based governance, as socially innovative agents. Social-innovation scholars say that bottom-linked governance proclaims solidarity-inspired forms of governance that will result in a more inclusive public participation emphasising human-centred partnership and a heterarchical form of governance [

50]. The spirit of involving all parties equally and communicatively is emphasised by providing space for each actor to be actively engaged in discussions and convey their aspirations. On the local side (NGOs and local communities), collaborating and initiating were a better option for forming environment-based local organisations and encouraging village governments to make locally pro-ecological policies. Then, on the upper-scale side, policymakers were slowly but surely informed about the existence and condition of small-island communities (one of which was Pahawang), supported empowerment, and provided policies supporting the initiation of sustainable livelihoods on small islands. At the provincial and district levels, policymakers interacted with the private sector and especially third parties (local communities, NGOs, and alliances) in a dialogue between different groups to design a regional strategic plan. This activity has been better served as a jumping-off point, in which the local community was not exploited as a sham to demonstrate the democratic application of the planning process by the upper-level administration. An inclusive policymaking practice positively impacted the small-island community (Pahawang), a distressed community that could be involved in policymaking regarding its livelihood and environment. As long as indigenous islanders have the space to voice their aspirations and implement true democracy, in which the local voice does matter and becomes a concern for the upper level of policymakers, adequate environment-led development that enhances sustainability on the small island can be achieved. In addition, the heterarchical atmosphere that is built can run successfully only if each agent has a mutual commitment as a common interest above the individuals’/groups’/elites’ interests, which can hinder the realisation of bottom-linked interaction.

6. Conclusions

We conducted this research by understanding enhanced capacity building as a process that combines Hess’s (1999) capacity building with social innovation and building (political) bargaining power. We took as a starting point the research question that underpins this paper: to what extent and in what ways are local actors (islanders and ‘non-profit-seeking’ actors) capable of developing capacity for a process of transformation and institutional innovation, enabling empowerment mechanisms and enhanced bargaining power? How do they settle and manage environmental and tourism-related problems, as well as promote alternative governance? The bottom-up governance arrangement as an alternative form of governance is the ultimate goal, with the aim of attaining sustainability that favours local communities in particular.

We argue that the success of the transformation of a small island depends on the active involvement of local communities in capacity-building practices, opening the pipeline for an empowerment process and local initiatives, increasing the inhabitant’s political bargaining power, and creating new local leaders capable of voicing their aspirations to the outside for the ecological benefit of the island, in addition to merely the economical aspect. Our analysis demonstrates that participation in ecological, sociocultural, and economic activities is insufficient to transform this island. Nonetheless, those aspects serve as a mechanism that emphasises the transformation process, allowing for increased horizontal collaboration (within the island’s population), vertical networking across the scales of the levels of policymakers, and involvement in changing policies that are more supportive of an island’s ecological development. The paper shows that, with the above achievements, bottom-linked management arrangements between agents lead to the achievement of sustainability goals on the small island—not just political decisions based on votes from ‘above’ but the implementation of power in the hands of many, and not in the hands of a few.

Through the perspective of social innovation, this research demonstrates that its three-dimensional focus was realised and has contributed to the island’s transformation process since 1997. The MB, in collaboration with the Pahawang residents, showcased the formation of socially innovative acts through the process of community capacity building, expanded networking, and political empowerment in terms of policymaking and participation. Regarding the consequent tension, MB dealt with it by maintaining interaction and dialogue with the resisters and assigning the latter a leadership role based on their great example and verbal influence.