Sustainable Development Goals and Islamic Social Finance: From Policy Divide to Policy Coherence and Convergence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

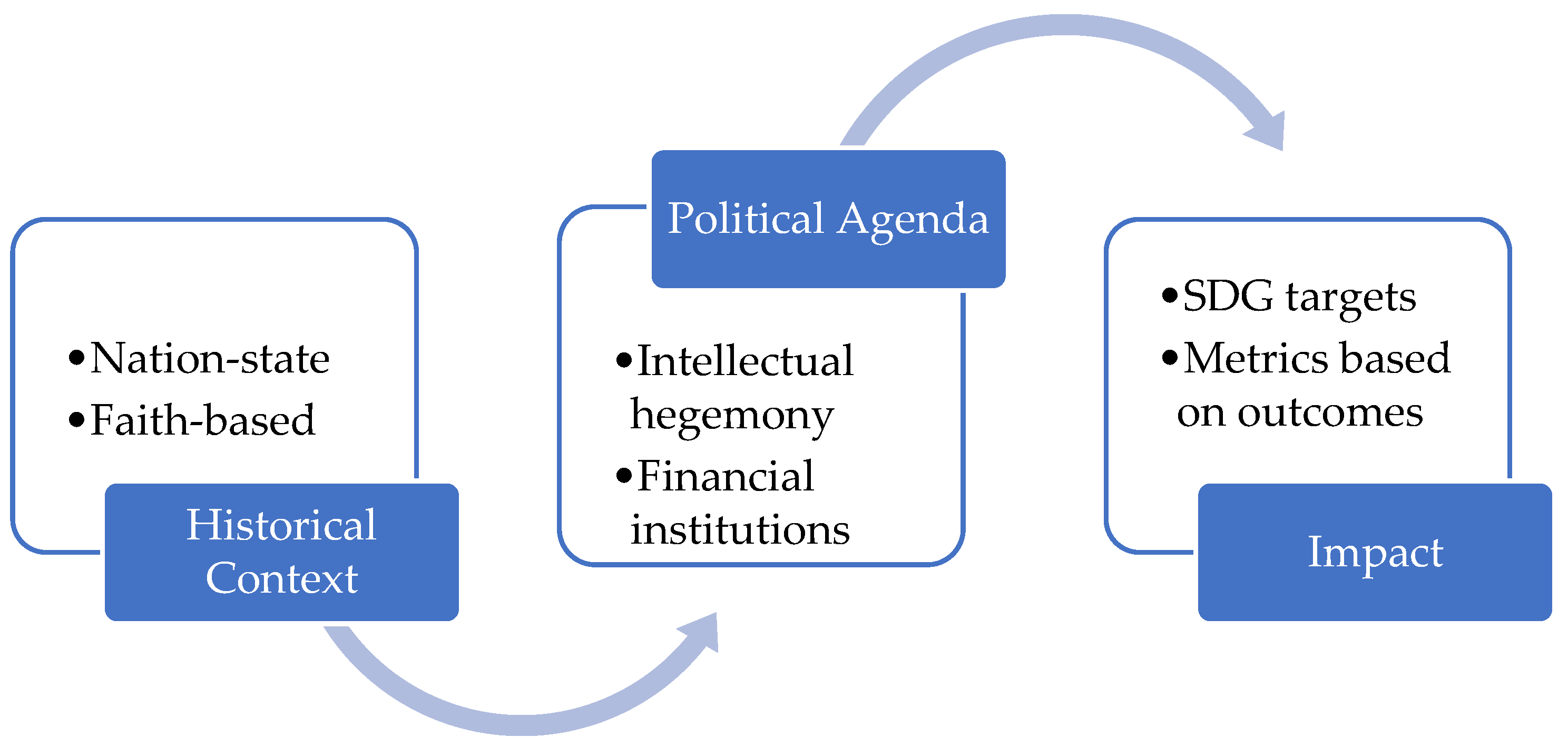

2. Policy Divide between Western and Muslim Countries

2.1. Describing Development

2.2. Ethicality and Morality of Development

2.3. Criticisms of Faith-Based Organizations

3. Historical Evolution of International Aid

3.1. Conventional Development Aid Cooperation Framework and Modalities

3.1.1. South–South Cooperation (SSC) Framework

3.1.2. North–South Cooperation (NSC) Framework

3.1.3. Triangular Cooperation (TrC) Framework

3.2. Global Sustainable Development Frameworks: MDGs and SDGs

3.3. Islamic Social Finance and Development Aid in Muslim Countries

3.3.1. Islamic Social Finance: A Faith-Based Aid Revolution

3.3.2. Potential of ISF Instruments

4. Case Studies

5. Discussion and Conclusions

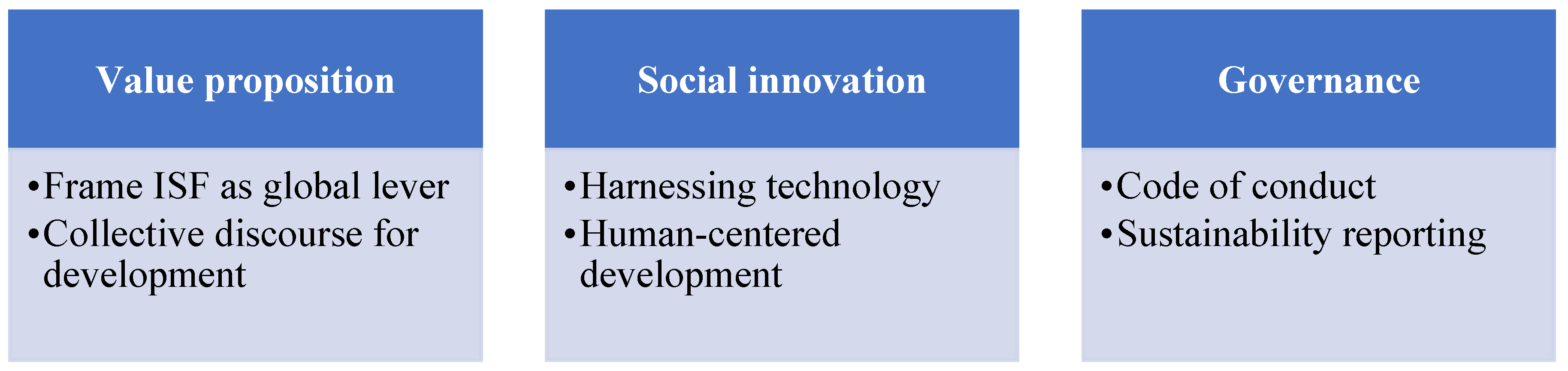

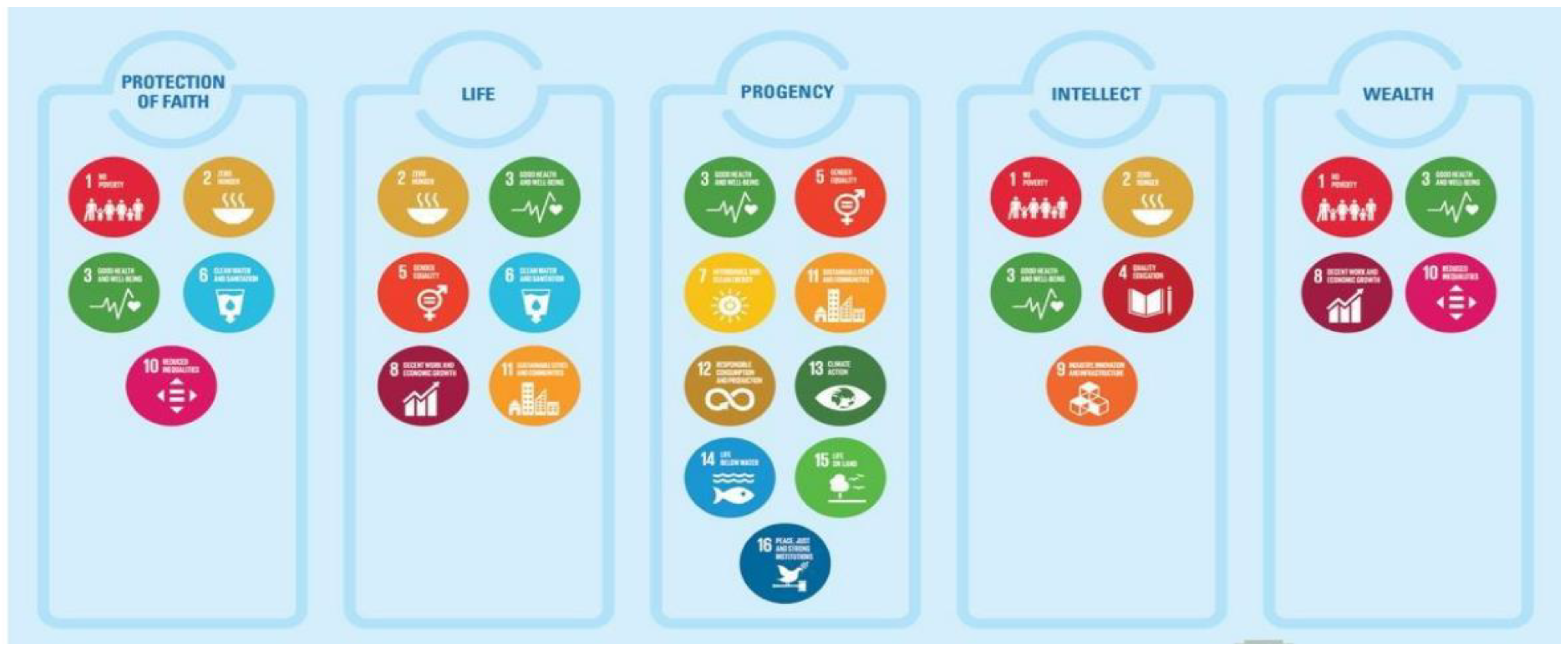

5.1. Aligning the ISF Instrument with the SDGs

5.2. Initiatives to Use ISF Instruments in Global Development Aid

5.3. Using ISF Instruments in Global Priorities: From Policy Divide to Convergence

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Jayyousi, O.R. Islam and Sustainable Development: New Worldviews; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.S. Religion and Development Aid: The Special Case of Islam; Clingendael Diplomacy Papers No. 8; Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rabasa, A.M.; Benard, C.; Chalk, P.; Fair, C.C.; Karasik, T.; Lal, R.; Lesser, I.; Thaler, D. The Muslim World After 9/11. In A Report Prepared for the US Airforce; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tomalin, E. Religions and Development; Routledge Perspectives on Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, A. Religion and Development Post-2015: Report of A Consultation Among Donor Organizations, United Nations Development Agencies and Faith-Based Organizations, New York. 2014. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/DONOR-UN-FBO%20May%202014.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Sardar, Z. Beyond Development: An Islamic Perspective. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 1996, 8, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R. Faith in Development: Coping with Paradox. INTRAC, No. 46. pp. 1–2. 2010. Available online: https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ONTRAC-46-Faith-in-Development-Coping-with-Paradox-2010.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- El Alaoui-Faris, M. Migrants’ Health, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Neurology in Migrants and Refugees; El Alaoui-Faris, M., Federico, A., Grisold, W., Eds.; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzara, F. Islamic finance and Sustainable Development Goals. A bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2021. Eur. J. Islam. Financ. 2021. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3857617 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Moretti, S. Between refugee protection and migration management: The quest for coordination between UNHCR and IOM in the Asia-Pacific region. Third World Q. 2021, 42, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health and Sustainable Development Goals Advisory Meeting: 18–19 June 2019, Copenhagen, Denmark. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/346161 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- UNHCR. UNHCR’s Refugee Population Statistics Database. 2022. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. Health in 2015: From MDGs, millennium Development goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/mdgs-sdgs (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- Rist, G. Development as a Buzzword. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.M.; Kymlicka, W. The Globalization of Ethics: Religious and Secular Perspectives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.; Stein, J. Sacred Aid: Faith and Humanitarianism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deneulin, S. Religion in Development: Rewriting the Secular Script; Zed books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, J. Religion and Development: Conflict or Cooperation? 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Selinger, L. Faith matters: Faith-based organizations, civil society and international development. J. Int. Dev. 2006, 18, 835–848. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn, J. The role of religion, spirituality and faith in development: A critical theory approach. Third World Q. 2009, 30, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambach, A. Religion, education, and secularism in international agencies. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2011, 55, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.; Ager, J. Faith and the discourse of secular humanitarianism. J. Refug. Stud. 2011, 24, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel Shah, T.; Stepan, A.; Toft, M.D. Rethinking Religion and World Affairs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G. Agents of transformation? Donors, faith-based organizations and international development. Third World Q. 2007, 28, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G. Faith-Based Organizations and International Development: An Overview. In Development, Civil Society and Faith-Based Organizations; Clarke, G., Jennings, M., Eds.; International Political Economy Series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Jennings, M.; Shaw, T. Development, Civil Society and Faith-Based Organizations: Bridging the Sacred and the Secular; International Political Economy Series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Haar, G.; Ellis, S. The role of religion in development: Towards a new relationship between the European Union and Africa. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2006, 18, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gottlieb, R.S. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planet’s Future, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, E. Faith and humanitarianism: It’s complicated. J. Refug. Stud. 2011, 24, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belshaw, D.; Calderisi, R.; Sugden, C. Faith in Development: Partnership between the World Bank and the Churches of Africa. 2001. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/0-8213-4848-5 (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Tyndale, W. Faith and economics in ‘development’: A bridge across the chasm? Dev. Pract. 2000, 10, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Sabelli, F. Faith and Credit: The World Bank’s Secular Empire, 1st ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heist, D.; Cnaan, R.A. Faith-Based International Development Work: A Review. Religions 2016, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R. Handle with care: Engaging with faith-based organizations in development. Dev. Pract. 2011, 21, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Petersen, M.J. Instrumental, narrow, normative? Reviewing recent work on religion and development. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, D. Western Faith-Based Organizations in Buddhist Cambodia: ‘Religious’ and ‘Secular’ Frames in Aid and Development. Master’s Thesis, The University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, K.B. Religion and Secularism in Development: Trends in the Approaches of Bilateral Donors in Canada and the United Kingdom. Master’s Thesis, The University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Landmark, K. Religion and Development in a Norwegian Context. A Qualitative Study of the Identity of Faith-Based Organizations and the Relationship to Their Secular Donor. Master’s Thesis, MF Norwegian School of Theology, Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.-M. Comparing the prevalence and organizational distinctiveness of faith-based and secular development NGOs in Canada. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2019, 30, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österinen, K. Development as Religious and Secular Concept. Master’s Thesis, Helsingin Yliopisto—University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baillie Smith, M.; Laurie, N.; Hopkins, P.; Olson, E. International volunteering, faith and subjectivity: Negotiating cosmopolitanism, citizenship and development. Geoforum 2013, 45, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, C. New Landscape of International Development Cooperation in Post-Covid-19-Implications for North-East Asia Countries. Un Escap North-East Asia Development Cooperation Forum Policy Brief. 2020. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/Policy%20Brief_CIDRN%20Li%20Xiaoyun%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Rosseel, P.; De Corte, E.; Blommaert, J.; Verniers, E. Approaches to North-South, South-South and North-South-South Collaboration. A Policy Document. 2009. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/63501 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Mehta, P.S.; Nanda, N. Trilateral Development Cooperation: An Emerging Trend. Briefing Paper, No. 1/2005, CUTS Centre for International Trade, Economics & Environment. 2005. Available online: http://www.cuts-international.org/pdf/BP1-2005.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- OECD. The OECD at 50: Development Co-Operation Past, Present and Future. In Development Cooperation Report 2011: 50th Anniversary Edition; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2011-7-en (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- OECD. Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation, OECD Development Assistance Committee, Paris. 1996. Available online: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/23/35/2508761.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Binka, F. North-South research collaborations: A move towards a true partnership? Trop. Med. Int. Health 2005, 10, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, G. South-South Cooperation Defies the North. Global Envision. 2006. Available online: http://www.globalenvision.org/library/8/1371 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- UNOSSC (n.d.). About South-South and Triangular Cooperation. Available online: https://www.unsouthsouth.org/about/about-sstc (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Dey, A. How relevant is North-South Cooperation in the Conventional and Unconventional Maritime Domain of Asia? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 157, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. How Islamic Finance Contributes to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. OECD Development Policy Paper No. 30. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/ac1480ca-en.pdf?expires=1629477190&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=92110EE3633FC75FAB04B223252A4B0C (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- UN. General Assembly: Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 27 July 2015. 2015. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ares69d313_en.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 2018. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- UN. Goal 17: Revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/globalpartnerships (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Islamic Research and Training Institute [IRTI]. I FOR IMPACT: Blending Islamic Finance and Impact Investing for the Global Goals. A Report published by the United Nations Development Programme, Istanbul International Center for Private Sector in Development. 2017. Available online: https://irti.org/product/i-for-impact-blending-islamic-finance-and-impact-investing-for-the-global-goals-2 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Yesuf, A.J.; Aassouli, D. Exploring synergies and performance evaluation between Islamic funds and socially responsible investment (SRIs) in light of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Heliyon 2020, 6, e04562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report: Investing in the ESGs: Action Plan. 2014. Available online: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2014_en.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- UNSDG. Unlocking SDG Financing: Findings from Early Adopters. 2018. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/unlocking-sdg-financing-findings-early-adopters (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Bloomberg. UN Seeks Investors for Projects to Meet 2030 Sustainable Goals. Bloomberg Green. 2021. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-14/un-seeks-investors-for-projects-to-meet-2030-sustainable-goals (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- ESCWA. International Dialogue on the Role of Islamic Social Financing in Achieving the SDGs. 2021. Available online: https://www.unescwa.org/news/international-dialogue-role-islamic-social-financing-achieving-sdgs (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Seiple, C.; Marshall, K.; Slim, H.; Roy, S. Strategic Religious Engagement in International Development: Building a Basic Baseline. Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 2021, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, R.; Mushtaq, A. The role of Islamic finance in sustainable development. J. Islam. Thought Civiliz. 2015, 5, 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- SESRIC. State of International Trade in Goods in OIC Countries. Webinar on International Trade in Goods, 06 April 2021. 2021. Available online: https://sesricdiag.blob.core.windows.net/sesric-site-blob/imgs/news/2461-SESRIC-Trade-Goods.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- SESRIC. OIC Economic Outlooks 2020. 2020. Available online: https://sesricdiag.blob.core.windows.net/sesric-site-blob/files/article/735.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Biancone, P.P.; Radwan, M. Social finance and unconventional financing alternatives: An overview. Eur. J. Islam. Financ. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Rabbani, M.R.; Abdullah, Y. Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 in MENA region and the Role of Islamic Finance. Int. J. Islam. Econ. Financ. 2021, 4, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Mohieldin, M.; Verbeek, J.; Aboulmagd, F. On the Sustainable Development Goals and the Role of Islamic Finance; The World Bank: Herndon, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kassim, S. Islamic finance and economic growth: The Malaysian experience. Glob. Financ. J. 2016, 30, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.A.; Pickup, F. Zakat for the SDGs. 2018. Available online: https://www.undp.org/blog/zakat-sdgs (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Ismail, A.G.; Shaikh, S.A. Where Is the Place for Zakat in SDGs? World Zakat Forum: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzaman, M.S.; Kurniaeny, F.K. Achieving sustainable impact of zakat in community development programs. Islam. Econ. Stud. 2019, 26, 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.A.; Pickup, F. Zakat for the SDGs. Islamic Finance News, 15 (34). Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2018/zakatfor-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Yahaya, M.H.; Ahmad, K. Financial Inclusion through Efficient Zakat Distribution for Poverty Alleviation in Malaysia: Using Fintech & Mobile Banking. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Management and Muamalah 2018 (ICoMM 2018), Bangi, Malaysia, 15–16 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Embong, M.R.; Taha, R.; Nor, M.N.M. Role of zakat to eradicate poverty in Malaysia. J. Pengur. 2013, 39, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah Aida, A.N.; Rashidah, A.R.; Normah, O. Zakat and poverty alleviation: Roles of zakat institutions in Malaysia. Int. J. Arts Commer. 2012, 1, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, N.M.; Abdullah, N. Is Zakat Capable of Alleviating Poverty? An Analysis on the Distribution of Zakat Fund in. J. Islam. Econ. Bank. Financ. 2014, 10, 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Van Oudheusden, P. The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring Financial Inclusion around the World. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7255, (April); The World Bank: Herndon, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, F.N.; Raji, F. Factors Contributing to Inefficient Management and Maintenance of Waqf Properties: A Literature Review. Int. J. Islam. Civiliz. Stud. 2018, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obaidullah, M.; Shirazi, N. Islamic Social Finance, a Chapter in a Book Global Report on Islamic Finance Islamic Finance: A Catalyst for Shared Prosperity? World Bank & Islamic Development Bank Group. 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25738 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Rehman, A. Islamic Finance for Social Good. 2019. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2019/IFN_ANNUAL_GUIDE_2019_Islamic_Social_Finance.html (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- OCHA. Global Humanitarian Overview. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GHO2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- DinarStandard. State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2019/20: Driving the Islamic Economy Revolution 4.0. 2019. Available online: https://cdn.salaamgateway.com/special-coverage/sgie19-20/full-report.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Vizcaino, R. Dubai Seeks Global Support for Islamic Endowment Reforms. 2013. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/islamic-endowments-dubai-idUSL5N0J527X20131121 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- IFRC. Beyond Charity—The Transformative Power of Zakat in Humanitarian Crises. 2018. Available online: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/beyond-charity-the-transformative-power-of-Zakat-in-humanitarian-crises-how-Zakat (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- UNICEF. The Global Muslim Philanthropy Fund for Children: An Innovative New Funding Platform from UNICEF and the Islamic Development Bank Group. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/partnerships/global-muslim-philanthropy-fund-for-children (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- IFRC. One WASH: Integrated Public Health, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Cholera Elimination. 2021. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/ifrc_onewash_20200429_v2_lr.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Shaikh, S.A.; Ismail, A.G. Role of Zakat in Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Zakat 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MICAD; OECD. Pilot Exercise on Broader Development Finance from the UAE. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-global-relations/Pilot%20Exercise%20on%20Broader%20Development%20Finance%20from%20the%20UAE.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- UNHCR. UNHCR Zakat Program: 2019 Launch Report: REFUGEES: THE MOST IN NEED OF ZAKAT FUNDS. 2019. Available online: https://Zakat.unhcr.org/hk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/UNHCR-Annual-Zakat-Report-2019-En.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Islamic Development Bank (IsDB). THE COVID-19 CRISIS AND ISLAMIC FINANCE RESPONSE OF THE ISLAMIC DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP. Discussion Draft. 2020. Available online: https://www.isdb.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2020-10/1.%20IsDB%20Group%20Report%20on%20Covid-19%20and%20Islamic%20Finance__FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- UN. HIGH-LEVEL CONFERENCE ON FINANCING FOR DEVELOPMENT AND THE MEANS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 2030 AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, Doha, Qatar. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/high-level-conference-on-ffd-and-2030-agenda/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/05/Doha-Conference-Publication.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- World Humanitarian Summit (WHC). Islamic Social Finance. Special Session Summary. Core Responsibility Five of the Agenda for Humanity. World Humanitarian Summit. Istanbul. 23–24 May 2016. 2016. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/world-humanitarian-summit-islamic-social-finance-special-session-summary-istanbul-23-24 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Helms, B.; Reille, X. Interest Rate Ceilings and Microfinance: The Story so Far; No. 33479; The World Bank: Herndon, VA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mia, M.A.; Rana, M.S. What affects portfolio yield of microfinance institutions? Evidence from Bangladesh. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cases | Modes of Financing | Actors and Roles | Targets | Interventions | Beneficiaries | Contribution to SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFRC’s Drought Relief Assistance Program: The Case of Kenya | Partnership: Zakat fund collected from Malaysia |

|

|

|

| SDG-1 (No Poverty); SDG-2 (Zero Hunger); SDG-6 (Clean Water and Sanitation); SDG-8 (Decent work and Economic Growth); SDG-13 (Climate Action); SDG-15 (Life on Land) |

| The Global Muslim Philanthropy Fund for Children (GMPFC) | Partnership: Philanthropic donor financing (Zakat and Sadaqat funds) |

|

|

|

| SDG-2 (Zero Hunger); SDG-3 (Good health and Well-being); SDG-4 (Quality Education); SDG-5 (Gender Equality); SDG-6 (Clean water and Sanitation) |

| Combat cholera and other diarrheal diseases: The Case of The One WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) Fund | Partnership: Philanthropic donor financing (Zakat and Sadaqat funds)Sukuk Issuance (a Shari’ah-compliant bond) |

|

|

|

| SDG-3 (Good Health and Well-being); SDG-6 (Clean Water and Sanitation); SDG-5 (Gender Equality); SDG-13 (Climate Action); SDG-17 (Partnership) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tok, E.; Yesuf, A.J.; Mohamed, A. Sustainable Development Goals and Islamic Social Finance: From Policy Divide to Policy Coherence and Convergence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116875

Tok E, Yesuf AJ, Mohamed A. Sustainable Development Goals and Islamic Social Finance: From Policy Divide to Policy Coherence and Convergence. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116875

Chicago/Turabian StyleTok, Evren, Abdurahman J. Yesuf, and Abdulfatah Mohamed. 2022. "Sustainable Development Goals and Islamic Social Finance: From Policy Divide to Policy Coherence and Convergence" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116875

APA StyleTok, E., Yesuf, A. J., & Mohamed, A. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals and Islamic Social Finance: From Policy Divide to Policy Coherence and Convergence. Sustainability, 14(11), 6875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116875