Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework

1. Introduction

2. Human Rights and the Environment: Synergies and Conflicts in the Business and Human Rights Context

2.1. Principles, Duty Bearers, Nature and Scope of Obligations

2.2. International Environmental and Human Rights Obligations in the Business and Human Rights Context

2.3. Recognition of a Right to a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment

3. The Emergence of the Environment in Corporate Responsibility and Business and Human Rights’ Discourses

3.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Environmental Responsibility

3.2. Business and Human Rights, and the Environment

“[N]early a third of cases alleged environmental harms that had corresponding impacts on human rights. Environmental concerns were raised in relation to all sectors. In these cases, various forms of pollution, contamination, and degradation translated into alleged impacts on a number of rights, including on the right to health, the right to life, rights to adequate food and housing, minority rights to culture, and the right to benefit from scientific progress. A number of environmental issues also prompted allegations that a firm had either impeded access to clean water or polluted a clean water supply, an issue raised in 20 per cent of cases [10] (para 27)”.

4. Articulating Human Rights and Environmental Accountability in the Absence of a Business, Human Rights and Environment Framework

4.1. Developing Joint Human Rights and Environment Transparency and Due Diligence Standards

4.2. Climate Litigation

“This is an obligation of results as regards the Shell group’s activities. With respect to the business relations of the Shell group, including the end-users, this constitutes a significant best-efforts obligation, in which context RDS may be expected to take the necessary steps to remove or prevent the serious risks ensuing from the CO2 emissions generated by them, and to use its influence to limit any lasting consequences as much as possible. A consequence of this significant obligation may be that RDS will forgo new investments in the extraction of fossil fuels and/or will limit its production of fossil resources. [149] (para 4.4.39)”.

5. Conclusions: Building the Foundations—Towards a Business, Human Rights and Environment Framework

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/40/55 (8 January 2019); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES/7/10/Add.1 (29 May 2019); IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://ipbes.net/document-library-catalogue/ipbes710add1 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- United Nations Secretary-General. Secretary-General’s Statement on the IPCC Working Group 1 Report on the Physical Science Basis of the Sixth Assessment, (9 August 2021). Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/secretary-generals-statement-the-ipcc-working-group-1-report-the-physical-science-basis-of-the-sixth-assessment (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- UN Human Rights Council. Resolution 19/10: Human Rights and the Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/RES/19/10, (19 April 2012); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Resolution 28/11: Human Rights and the Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/RES/28/11, (6 April 2015); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Doc A/RES/70/1 (21 October 2015); UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Resolution 48/13: The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/RES/48/13 (18 October 2021); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises—Corporations and Human Rights: A Survey of the Scope and Patterns of Alleged Corporate-Related Human Rights Abuse; UN Doc A/HRC/8/5/Add.2, (23 May 2008); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights—Climate Change and Poverty; UN Doc A/HRC/41/39 (17 July 2019); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, P. The Carbon Majors Database—CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017 (July 2017). Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en/articles/media/new-report-shows-just-100-companies-are-source-of-over-70-of-emissions (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment—Human Rights and the Global Water Crisis: Water Pollution, Water Scarcity and Water-Related Disasters; UN Doc A/HRC/46/28 (19 January 2021); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises—Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework; UN Doc A/HRC/17/31 (21 March 2011), Annex; UN Human Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Resolution 26/9: Elaboration of an International Legally Binding Instrument on Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights; UN Doc A/HRC/RES/26/9 (14 July 2014); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Resolution 2398 (XXIII)—Problems of the Human Environment (1968); UN Doc A/RES/2398(XXIII); UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, Sweden, 5–16 June 1972. UN Doc A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1, 11 ILM 1416.

- Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. UN Doc. A/CONF.156/26 (Vol. I), 31 ILM 874.

- Turner, S.J. A Substantive Environmental Right: An Examination of the Legal Obligations of Decision-Makers Towards the Environment; Kluwer Law International: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K.; Anton, D.K.; Shelton, D.L. Environmental Protection and Human Rights; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.M.M.; Martin-Ortega, O. International Law; Sweet and Maxwell: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, C. From a Vicious to a Virtuous Circle: Addressing Climate Change, Environmental Destruction and Contemporary Slavery (Anti-Slavery, 2021). Available online: https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ASI_ViciousCycle_Report_web2.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights—Analytical Study on the Relationship Between Human Rights and the Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/19/34 (16 December 2011); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Committee. General Comment No. 36—Article 6: Right to Life; UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/36, (3 September 2019); UN Human Rights Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment—Preliminary Report; UN Doc A/HRC/22/43, (24 December 2012); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. The Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment. In Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/37/59 (24 January 2018), Annex; UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kawas-Fernández, v.H. Judgement (Merits, Reparations and Costs), Inter-American Court of Human Rights Series C No. 196 (3 April 2009). Available online: https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_196_ing.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, John, H. Knox—Mapping Report; UN Doc A/HRC/25/53 (30 December 2013); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

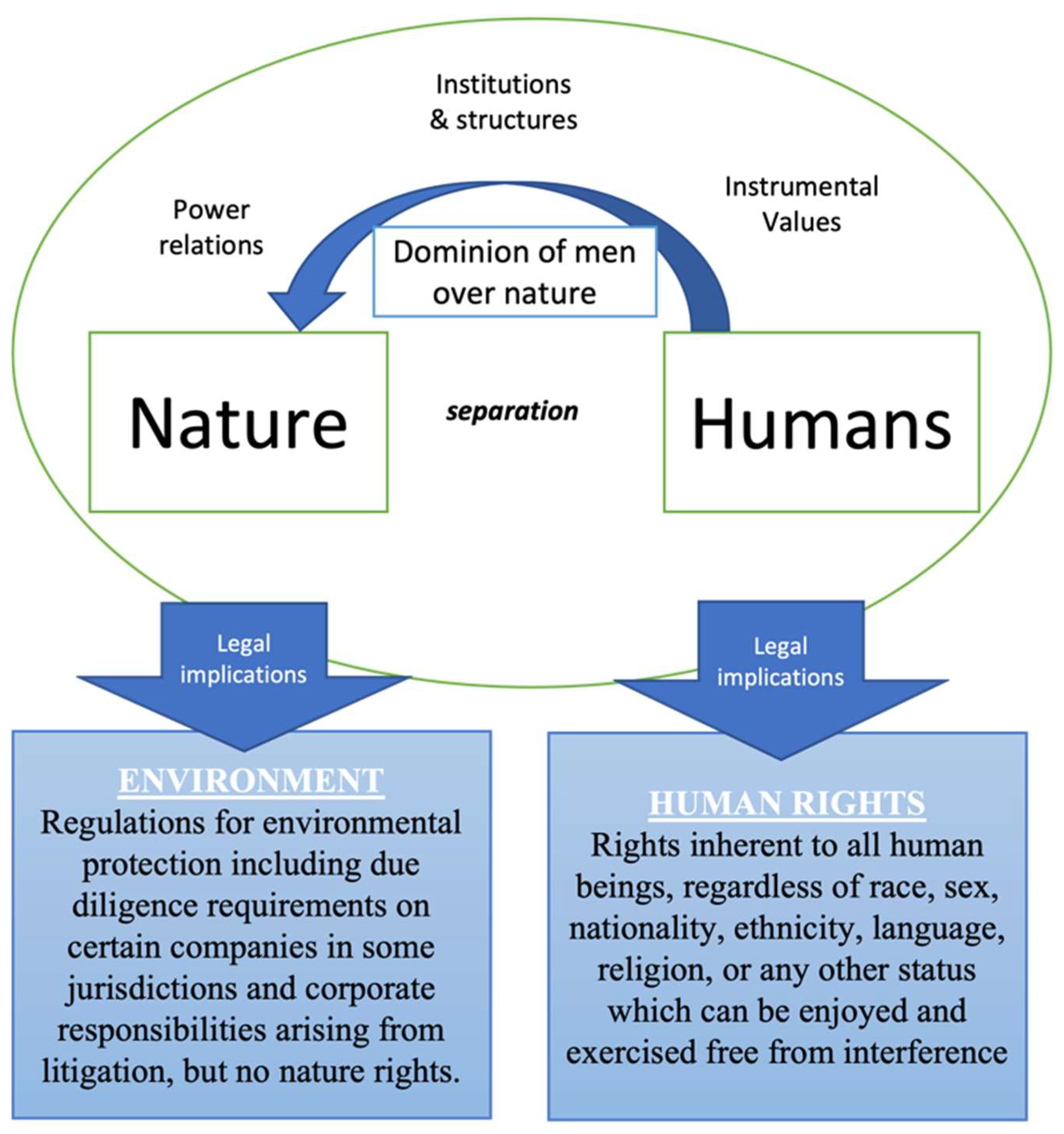

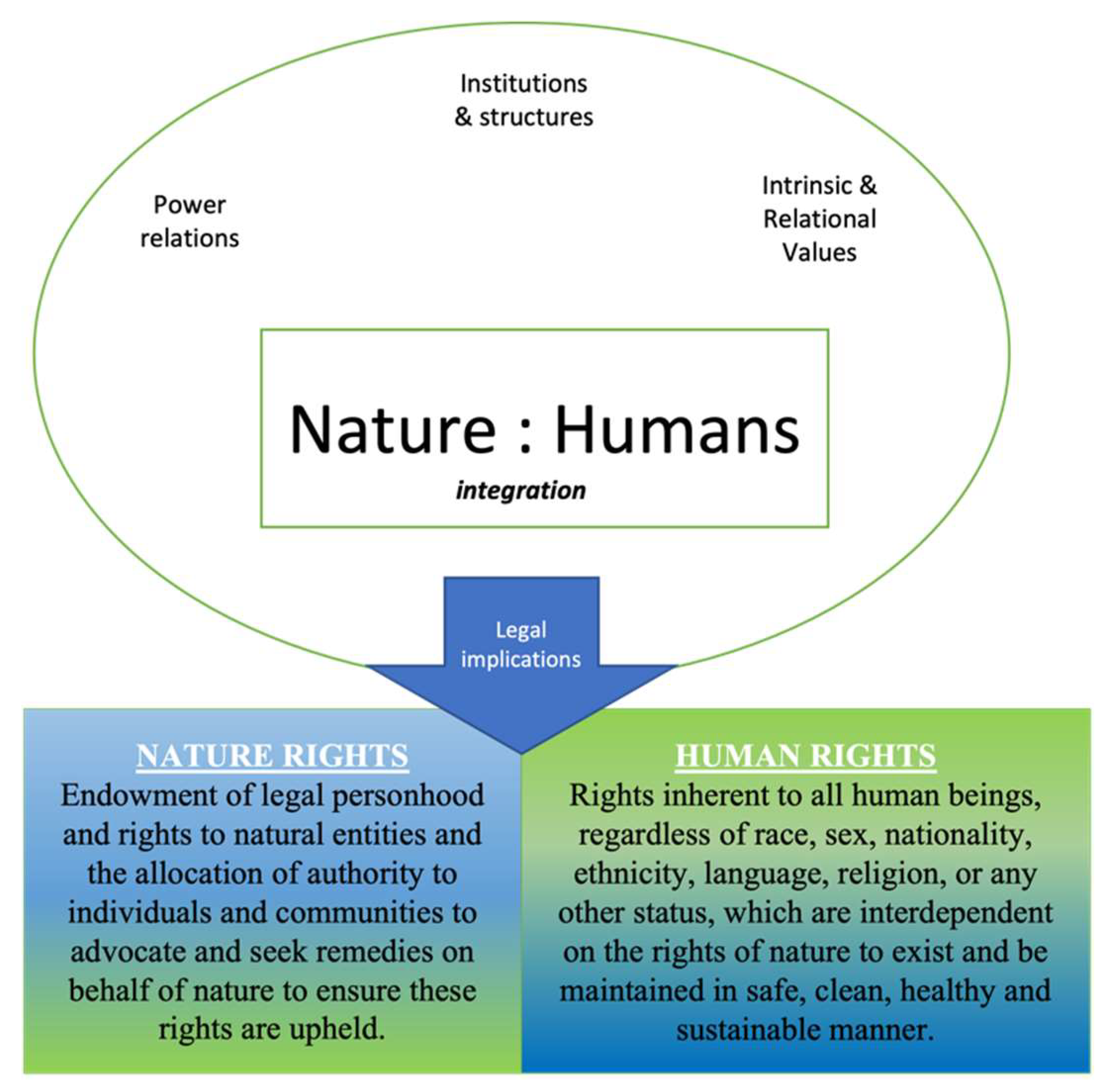

- Turner, S.J. Business, Human Rights and the Environment—Using Macro Legal Analysis to Develop a Legal Framework That Coherently Addresses the Root Causes of Corporate Human Rights Violations and Environmental Degradation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantekas, I.; Oette, L. International Human Rights Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, P.; Peel, J.; Fabra, A.; MacKenzie, R. Principles of International Environmental Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Committee. General Comment 23: The Rights of Minorities (art. 27); UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.5 (8 April 1994); UN Human Rights Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Ortega, O. Empresas Multinacionales y Derechos Humanos en Derecho Internacional; Bosch: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenhole, W. Obligations and responsibility in a plural and diverse duty-bearer human rights regime. In Challenging Territoriality in Human Rights Law. Building Blocks for a Plural and Diverse Duty-Bearer Regime.; Vandenhole, W., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, C.M.; Sheeham, L. The Rights of Nature: Guiding Our Responsibilities through Standards. In Environmental Rights. The Development of Standards.; Turner, S.J., Shelton, D.L., Razaque, J., McIntire, O., May, J.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 342–366. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Y.; Schoukens, H. A positivist approach to rights of nature in the European Union. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 2021, 12, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Political Database of the Americas. Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador 2008. Available online: https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Macpherson, E.; Torres Ventura, J.; Clavijo Ospina, F. Constitutional Law, Ecosystems, and Indigenous Peoples in Colombia: Biocultural Rights and Legal Subjects. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2020, 9, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesche, P. Rights of Nature in Practice: A Case Study on the Impacts of the Colombian Atrato River Decision. J. Environ. Law 2021, 33, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryner, N. Colombian Supreme Court Recognizes Rights of the Amazon River Ecosystem. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/news/world-commission-environmental-law/201804/colombian-supreme-court-recognizes-rights-amazon-river-ecosystem (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Jiang, B.; Ugirashebuja, E.; de Boer, D.; Fan, D. 10 Landmark Cases for Biodiversity. Available online: https://www.clientearth.org/latest/documents/10-landmark-cases-for-biodiversity/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Gonzalez, C.G. Bridging the North-South Divide: International Environmental Law in the Anthropocene. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 2015, 32, 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic, M. Extraterritorial Application of Human Rights Treaties: Law, Principles and Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Methven O’Brien, C. The Home State Duty to Regulate the Human Rights Impacts of TNCs Abroad: A Case of Extraterritorial Overreach? Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2018, 3, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, 2161 UNTS 447, 38 ILM 516 (1998). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=XXVII-13&chapter=27 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (adopted 4 March 2018, Entered into Force 22 April 2021). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-18&chapter=27&clang=_en (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment No. 24 (2017) on State Obligations Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the context of Business Activities; UN Doc E/C.12/GC/24 (10 August 2017); UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/31/52 (1 February 2016); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/74/161 (15 July 2019); UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. General Recommendation No. 37 (2018) on the Gender-Related Dimensions of Disaster Risk Reduction in the Context of Climate Change; UN Doc CEDAW/C/GC/37 (13 March 2018); UN: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/37/58 (24 January 2018); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, Margaret Sekaggya; UN Doc A/HRC/19/55 (21 December 2011); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, E.; Karim, N.; Mohanraj, P.; Wu, D. Measuring Gender-Transformative Change: A Review of Literature and Promising Practices (October 2015). Available online: https://www.care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/working_paper_aas_gt_change_measurement_fa_lowres.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya–Extractive Industries Operating Within or Near Indigenous Territories; UN Doc A/HRC/18/35 (11 July 2011); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, David, R. Boyd—Human Rights Depend on a Healthy Biosphere; UN Doc A/75/161 (15 July 2020); General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Don’t Pollute My Future! The Impact of the Environment on Children’s Health, (March 2017). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-IHE-17.01 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- UNICEF. Unless We Act Now—The Impact of Climate Change on Children. (November 2015). Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/unless-we-act-now-impact-climate-change-children (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/HRC/37/59 (24 January 2018); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment; UN Doc A/73/188 (19 July 2018); UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.; Knox, J.; Limon, M. The Time is Now—the Case for Universal Recognition of the Right to a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. (Universal Rights Group, 2021). Available online: https://www.universal-rights.org/urg-policy-reports/the-time-is-now-the-case-for-universal-recognition-of-the-right-to-a-safe-clean-healthy-and-sustainable-environment/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment—Right to a Healthy Environment: Good Practices; UN Doc A/HRC/43/53, (30 December 2019); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN Core Group on Human Rights and the Environment. Joint Statement (September 2020). Available online: https://www.genevaenvironmentnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/StatementCoreGroupHRE_towardsGlobalRecognition.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- UN Core Group on Human Rights and the Environment. Joint Statement (March 2021). Available online: http://healthyenvironmentisaright.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Core-Group-Joint-Statement.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- UN OHCHR, Joint Statement by UN Human Rights Experts for World Environment Day’ (5 June 2021) Recognition of the Right to a Healthy Environment Key to Address the Environment Crisis and Protect Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=27130&LangID=E (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Muchlinksi, P. Multinational Enterprises and the Law; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasastry, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Versus Business and Human Rights: Bridging the Gap Between Responsibility and Accountability. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 14, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBarnet, D.; Voiculescu, A.; Campbell, T. The New Corporate Accountability: Corporate Social Responsibility and The Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, R. The Changing Nature of Corporate Social Responsibility: CSR and Development–The Case of Mauritius; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Okoye. Legal Approaches and Corporate Social Responsibility: Towards a Llewellyn’s Law-Jobs Approach; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.W. Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility around the World: Emergent Varieties and National Experiences. Univ. Pa. J. Bus. Law 2021, 23, 429–469. [Google Scholar]

- Deva, S.; Ramasastry, A.; Wettstein, F.; Santoro, M. Editorial: Business and Human Rights Scholarship: Past Trends and Future Directions. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2019, 4, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ireland, P.; Pillay, R.G. Corporate Social Responsibility in a Neoliberal Age in Corporate Social Responsibility and Regulatory Governance: Towards Inclusive Development? Utting, P., Marques, J., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2010; pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.R. The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Can Business Afford to Ignore Corporate Social Responsibilities? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. The Growing Concern Over Business Responsibility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votaw, D. The Politics of a Changing Corporate Society. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1961, 3, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votaw, D. Genius Becomes Rare: A Comment on the Doctrine of Corporate Social Responsibility Pt 1. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1972, 15, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.W. Business and Society; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Managing Corporate Social Responsibility; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, F. The history of ‘business and human rights’ and its relationship with corporate social responsibility. In Research Handbook on Human Rights and Business; Deva, S., Birchall, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 23–62. [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Economic Development. Social Responsibilities of Business Corporations; Committee for Economic Development: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises—Human Rights Policies and Management Practices: Results from Questionnaire Surveys of Governments and Fortune Global 500 Firms; UN Doc A/HRC/4/35/Add.3 (28 February 2007); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, N. Shaping Corporate Environmental Performance. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, M.J. Risk Society and Ecological Modernisation: Alternative Visions for Post-industrial Nations. Futures 1997, 29, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.; Groenewegen, P.; Hofman, P.S. Ahead of the Curve: Cases of Innovation in Environmental Management.; Kluwer: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sjåfjell, B.; Bruner, C.M. Introduction. In The Cambridge Handbook of Corporate Law, Corporate Governance and Sustainability; Sjåfjell, B., Bruner, C.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, V.; Flint, M. Critical reflections on responsible business initiatives and systemic constraints for achieving a safe and just operating space for humanity. In Business and Development Studies: Issues and Perspectives; Lund-Thomsen, P., Hansen, M., Lindgreen, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deva, S. From ‘business or human rights’ to ‘business and human rights’: What next? In Research Handbook on Human Rights and Business; Deva, S., Birchall, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (1976). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/publicationsdocuments/legalactsstandards/5/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- ILO ‘Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (1977). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ILO_Chronology/declaration_1977_engl.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Wallace, R.; Martin-Ortega, O. The UN Norms: A First Step to Universal Regulation of Transnational Corporations’ Responsibilities for Human Rights? Dublin Univ. Law J. 2004, 26, 304–319. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi, C. The Climate Change Dimension of Business and Human Rights: The Gradual Consolidation of Concept of ‘Climate Due Diligence. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2021, 6, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, C.; Bernaz, N. Business, Human Rights and Climate Due Diligence: Understanding the Responsibility of Banks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights. Second Revised Draft—Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate. In International Human Rights Law, The Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises (6 August 2020); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/WGTransCorp/Session6/OEIGWG_Chair-Rapporteur_second_revised_draft_LBI_on_TNCs_and_OBEs_with_respect_to_Human_Rights.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Methven O’Brien, C. Confronting the Constraints of the Medium: The Fifth Session of the UN Intergovernmental Working Group on a Business and Human Rights Treaty. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2020, 5, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven O’Brien, C. Transcending the Binary: Linking Hard and Soft Law Through a UNGPS-Based Framework Convention. ASIL Unbound 2020, 114, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights, Third Revised Draft—Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate. In International Human Rights Law, The Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises (17 August 2021); UN Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/WGTransCorp/Session6/LBI3rdDRAFT.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Turner, S.J. A Global Environmental Right; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sjåfjell, B. How company law has failed human rights—And what to do about it. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2020, 5, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2011). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/48004323.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Narine, M. Disclosing Disclosure’s Defects: Addressing Corporate Irresponsibility for Human Rights Impacts. Columbia Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2015, 47, 84–150. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Ortega, O. Transparency and human rights in global supply chains: From corporate led disclosure to a right to know. In Research Handbook on Global Governance, Business and Human Rights; Marx, A., Van Calster, G., Wouters, J., Otteburn, K., Lica, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Koekkoek, M.; Marx, A.; Wouters, J. Monitoring Forced Labour and Slavery in Global Supply Chains: The Case of the California Act on Transparency in Supply Chains. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (2010). Available online: https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/cybersafety/sb_657_bill_ch556.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- The UK Modern Slavery Act (2015). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- The Australia Modern Slavery Act (2018). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018A00153 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- The French Duty of Vigilance Law (2017). Unofficial English Translation. Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/french-duty-of-vigilance-law-english-translation/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- The Dutch Child Labour Law (2020). Unofficial English Translation. Available online: https://www.ropesgray.com/en/newsroom/alerts/2019/06/Dutch-Child-Labor-Due-Diligence-Act-Approved-by-Senate-Implications-for-Global-Companies (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act (2010). Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-9515/pdf/COMPS-9515.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- The EU Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 Laying Down Supply Chain Due Diligence Obligations for Union Importers of Tin, Tantalum and Tungsten, Their Ores, and Gold Originating from Conflict-Affected Areas and High-Risk Areas. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32017R0821 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Commission, Impact Assessment COM (2013) 207 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SWD:2013:0127:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Martin-Ortega, O.; Hoekstra, J. Reporting as a Means to Protect and Promote Human Rights? The EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive. Eur. Law Rev. 2019, 44, 622–645. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting (Methodology for Reporting Non-Financial Information) (2017/C 215/01). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017XC0705%2801%29 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting: Supplement on Reporting Climate-Related Information (2019/C 209/01). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019XC0620%2801%29 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Communication from the Commission. The European Green Deal, COM/2019/640 Final. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2019-640-final (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- European Commission, Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- European Commission. Questions and Answers: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Proposal, (21 April 2021). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_1806 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Savourey, E.; Brabant, S. The French Law on the Duty of Vigilance: Theoretical and Practical Challenges Since Its Adoption. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2021, 6, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notre Affaire à Tous, ‘Benchmark de la Vigilance Climatique des Multinationales, Rapport Général’ [General Report Benchmarking the Climate Vigilance of Multinational Companies]’ (March 2020). Available online: https://notreaffaireatous.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Rapport-General-Multinationales-NAAT-2020.02.01.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Schilling-Vacaflor, S. Integrating Human Rights and the Environment in Supply Chain Regulations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative Lieferkettengesetz. What the New Supply Chain Act Delivers and What It Doesn’t, (11 June 2021). Available online: https://lieferkettengesetz.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Initiative-Lieferkettengesetz_Analysis_What-the-new-supply-chain-act-delivers.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Nelson, V.; Martin-Ortega, O.; Flint, M. Making Human Rights Due Diligence Work for Small Farmers and Workers in Global Supply Chains (Fairtrade Advocacy Office and Bort fur Deiwelt, 2020. Available online: https://fairtrade-advocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/UoG-HRDD-Full-Report-60pp-FINAL-SECURED.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Bright, C.; Buhmann, K. Risk-based due diligence, climate change, human rights and the just transition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven O’Brien, C.; Martin-Ortega, O. Human rights and public procurement of goods and services. In Research Handbook on Human Rights and Business; Deva, S., Birchall, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño-Lozano, L. Sustainable Public Procurement and Human Rights: Barriers to Deliver on Socially Sustainable Road Infrastructure Projects in Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, J.; Higham, C. Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation; 2021 Snapshot; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Global-trends-in-climate-change-litigation_2021-snapshot.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Savaresi, A.; Setzer, J. Mapping the Whole of the Moon: An Analysis of the Role of Human Rights in Climate Litigation, (18 February 2021). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3787963 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Ganguly, G.; Setzer, J.; Heyvaert, V. If at First you Don’t Succeed: Suing Corporations for Climate Change. Oxf. J. Leg. Stud. 2018, 38, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, M.B. Counter Corporate Litigation: Remedy, Regulation and Repression in the Struggle for a Just Transition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherpa. Climate Change Litigation against Total: A First Victory for the NGOs and Local Authorities. Available online: https://www.asso-sherpa.org/climate-change-litigation-against-total-a-first-victory-for-the-ngos-and-local-authorities (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Climate Case Chart. Notre Affaire a Tous and Others v Total. Available online: http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/notre-affaire-a-tous-and-others-v-total/ (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (LSE). Notre Affaire a Tous and Others v Total. Available online: https://climate-laws.org/geographies/france/litigation_cases/notre-affaire-a-tous-and-others-v-total (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Notre Affaire a Tous and Others v Total, Unofficial Translation of the Complaint. Available online: http://blogs2.law.columbia.edu/climate-change-litigation/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/non-us-case-documents/2020/20200128_NA_complaint.pdf>accessed (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Saul Ananias Luciano Lliuya v RWE AG, District Court of Essen (15 December 2016), Case 2 O 285/15 (Unofficial English translation). Available online: http://blogs2.law.columbia.edu/climate-change-litigation/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/non-us-case-documents/2016/20161215_Case-No.-2-O-28515-Essen-Regional-Court_decision-1.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (LSE). Lliuya v RWE. Available online: https://climate-laws.org/geographies/germany/litigation_cases/luciano-lliuya-v-rwe (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Saul Ananias Luciano Lliuya v RWE AG, Order of the Higher Regional Court of Hamm: Order on Defendant’s Argument of December 14, 2017 (1 February 2018) (English Translation) (Lliuya v RWE). Available online: http://blogs2.law.columbia.edu/climate-change-litigation/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/non-us-case-documents/2018/20180207_Case-No.-2-O-28515-Essen-Regional-Court_order.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Vedanta Resources PLC and Another v Lungowe and Others [2019] UKSC 20. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2017-0185.html (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Okpabi and Others v Royal Dutch Shell Plc [2021] UKSC 3. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2018-0068.html (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Varvastian, S.; Kalunga, F. Transnational Corporate Liability for Environmental Damage and Climate Change: Reassessing Access to Justice after Vedanta v Lungowe. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2020, 9, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgenda Foundation v The State of the Netherlands, District Court of the Hague (24 June 2015), Case C/09/456689/HAZA 13-1396 (English Translation). Available online: http://blogs2.law.columbia.edu/climate-change-litigation/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/non-us-case-documents/2015/20150624_2015-HAZA-C0900456689_decision-1.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- The State of the Netherlands v Urgenda Foundation, The Hague Court of Appeal (9 October 2018), Case 200.178.245/01 (English Translation). Available online: https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2018:2610 (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- The State of Netherlands v Urgenda Foundation, The Supreme Court of the Netherlands (20 December 2019), Case 19/00135 (English Translation). Available online: https://www.urgenda.nl/wp-content/uploads/ENG-Dutch-Supreme-Court-Urgenda-v-Netherlands-20-12-2019.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Wewerinke-Singh, M.; McCoach, A. The State of the Netherlands v Urgenda Foundation: Distilling best practice and lessons learnt for future rights-based climate litigation. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milieudefensie and others v Royal Dutch Shell, District Court of the Hague, (26 May 2021), Case C/09/571932/HA ZA 19-379 (English Translation). Available online: http://climatecasechart.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/non-us-case-documents/2021/20210526_8918_judgment-1.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (LSE). Milieudefensie et al. v Royal Dutch Shell plc. Available online: https://climate-laws.org/geographies/netherlands/litigation_cases/milieudefensie-et-al-v-royal-dutch-shell-plc (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Dutch Civil Code, Book 6: The law of Obligations, Section 6.3.1 General Provisions, Article 6:162, Definition of a ‘Tortious Act’. Available online: http://www.dutchcivillaw.com/legislation/dcctitle6633.htm#162 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Ambrose, J. Oil Giant Shell Set to Appeal Against Ruling on Carbon Emissions. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/20/oil-giant-shell-set-to-appeal-ruling-on-carbon-emissions (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Lizarazo-Rodriguez, L. The UNGPs on Business and Human Rights and the Greening of Human Rights Litigation: Fishing in Fragmented Waters? Sustainability 2021, 13, 10516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martin-Ortega, O.; Dehbi, F.; Nelson, V.; Pillay, R. Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116596

Martin-Ortega O, Dehbi F, Nelson V, Pillay R. Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116596

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartin-Ortega, Olga, Fatimazahra Dehbi, Valerie Nelson, and Renginee Pillay. 2022. "Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116596

APA StyleMartin-Ortega, O., Dehbi, F., Nelson, V., & Pillay, R. (2022). Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework. Sustainability, 14(11), 6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116596