Long-Term Impact of Interregional Migrants on Population Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

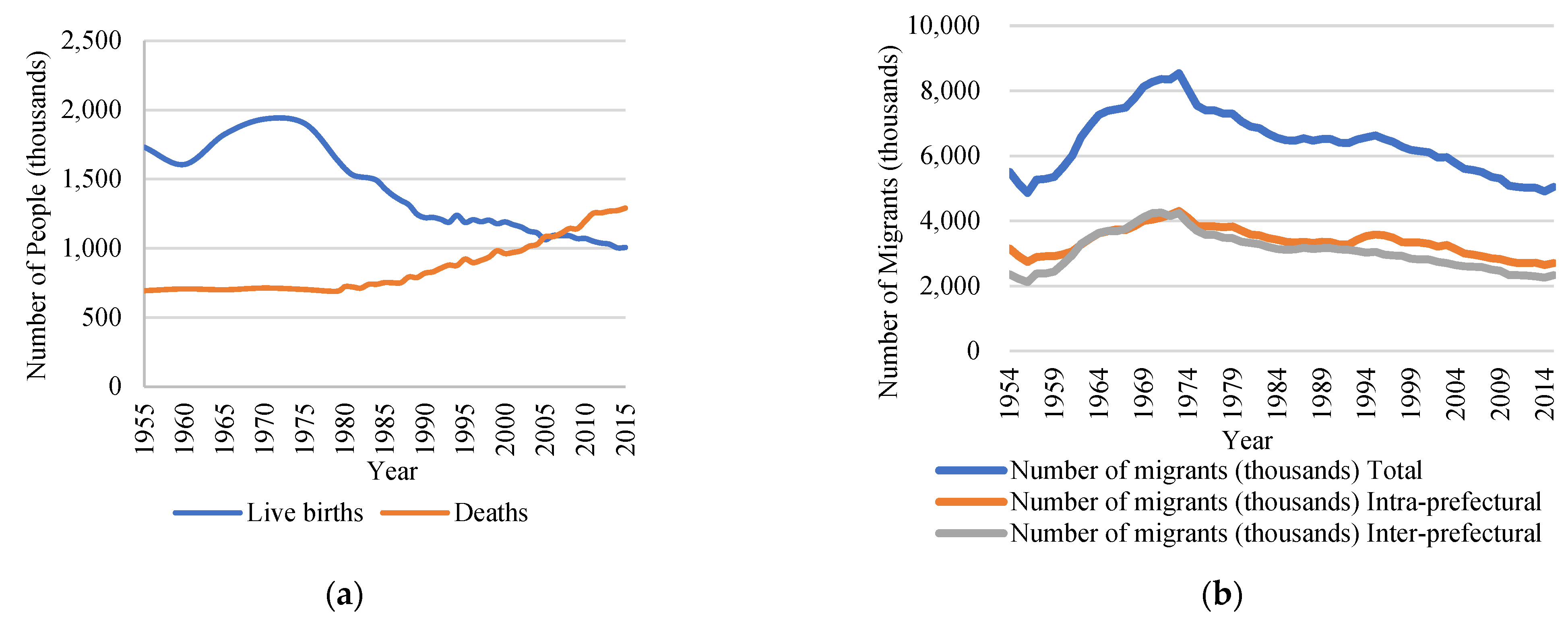

3. Description of the Japanese Population, Migration, and Urbanization Trends

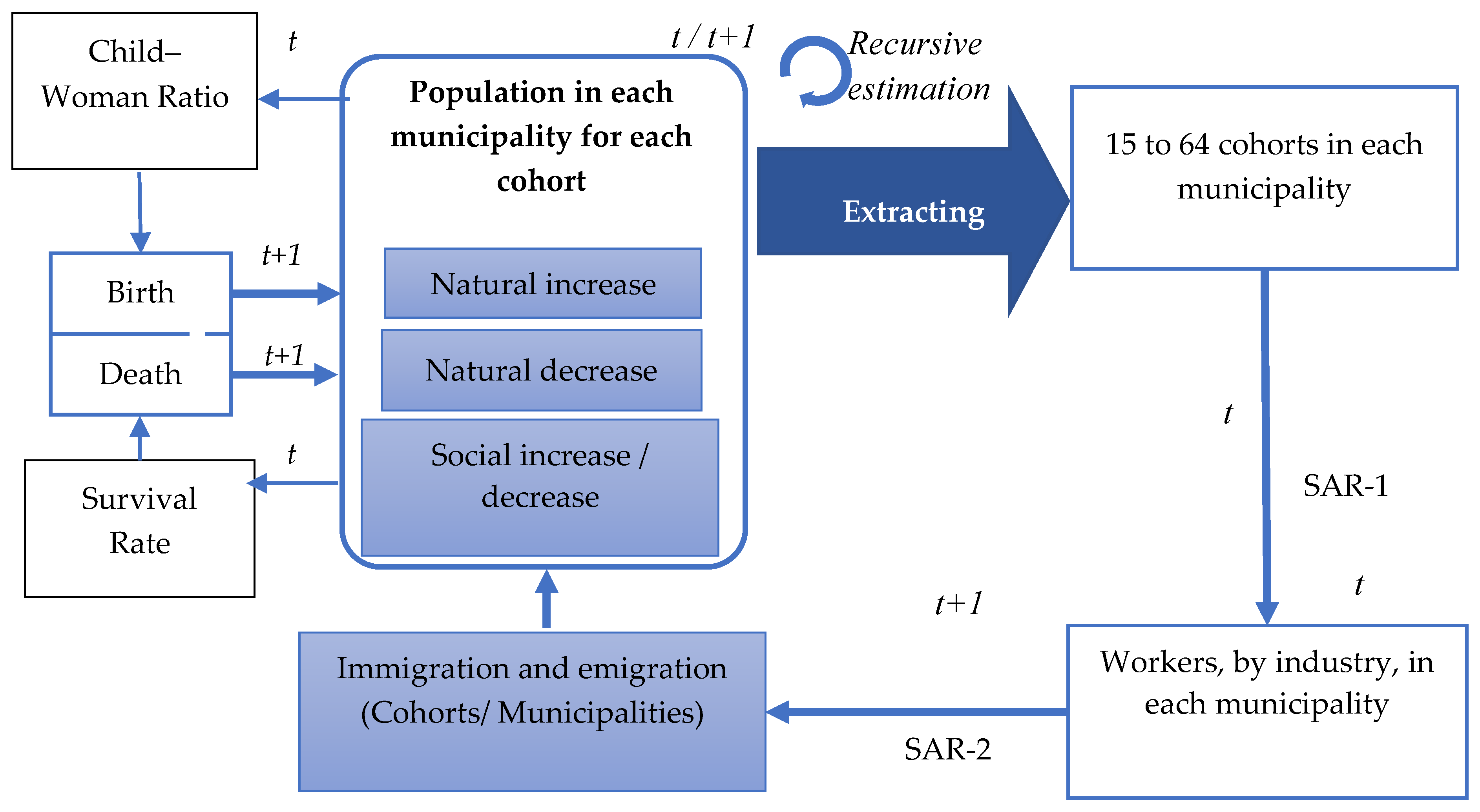

4. Existing Methodology: Cohort Component Analysis

| Parameter | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Initial Population (Pin (i, x∼x + n)) | (2010) 5-year age cohorts for both sexes in Japan at the municipality level. |

| Survival Rate (S i, x∼x + n) | |

| Cohort Age-specific Child–Women Ratio (CWR i, x∼x + n) | |

| Relative Disparities forCWRi, t (R i) | |

| Child–Women Ratio () or Fertility Rate () | , is adopted from national population projection data. |

| Sex Ratio (SR) for Ages 0–4 |

5. Proposed Model System: Integration of CCA with the SAR Model

5.1. Spatial Autoregressive Model (SAR)

5.2. Summary of SAR Estimation

6. Discussion

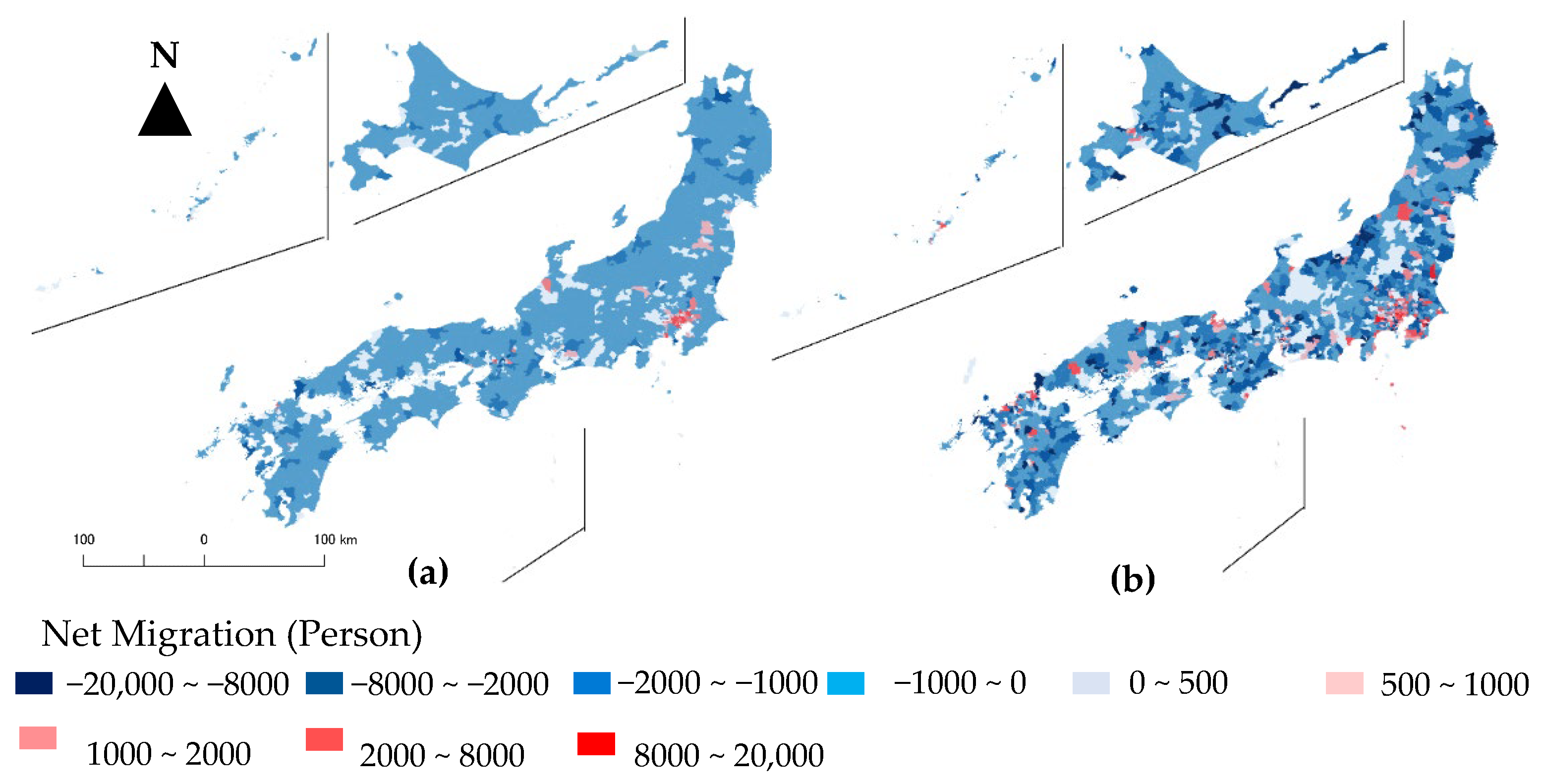

6.1. Comparison between CCA Output and the Proposed Approach

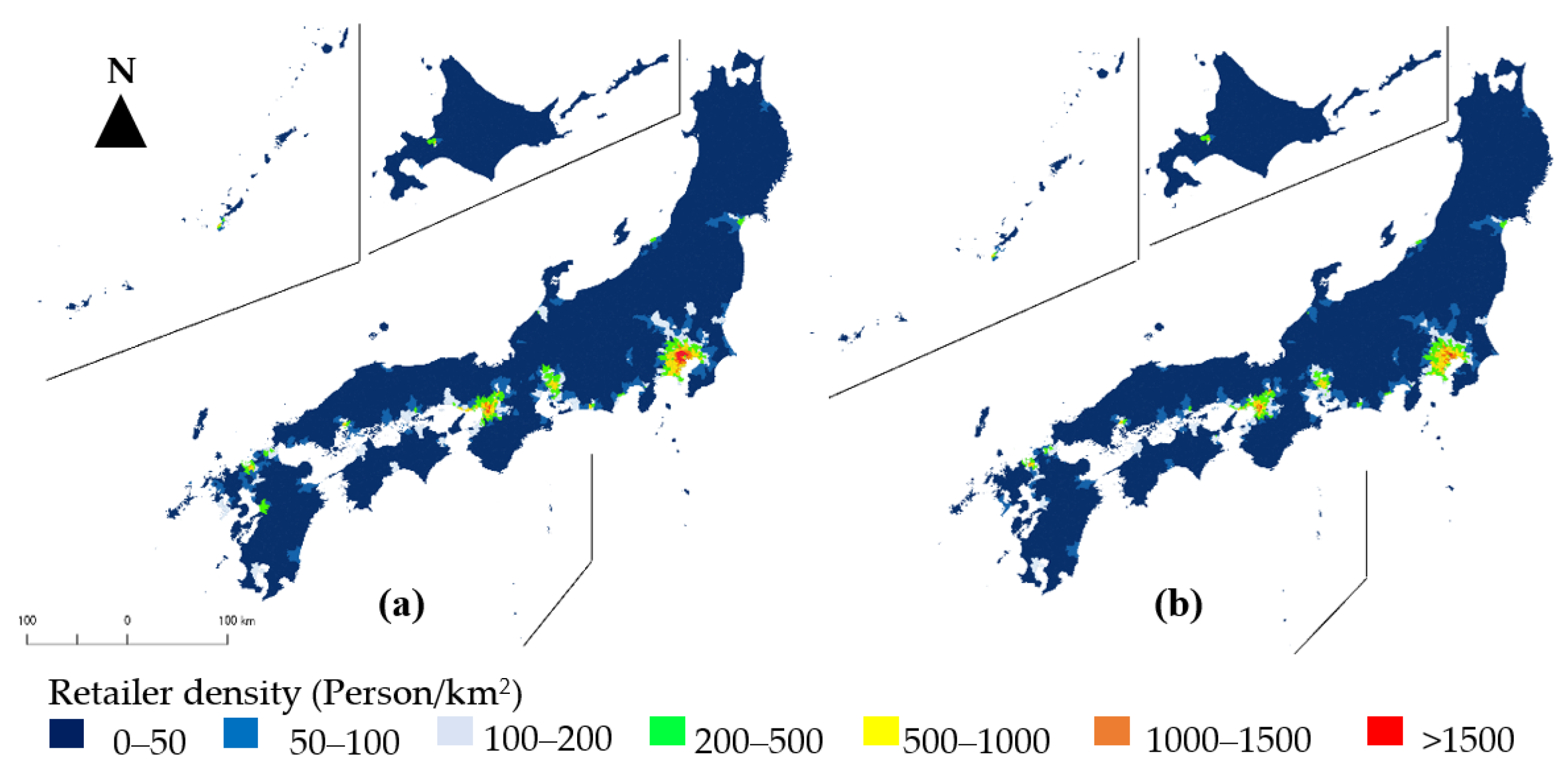

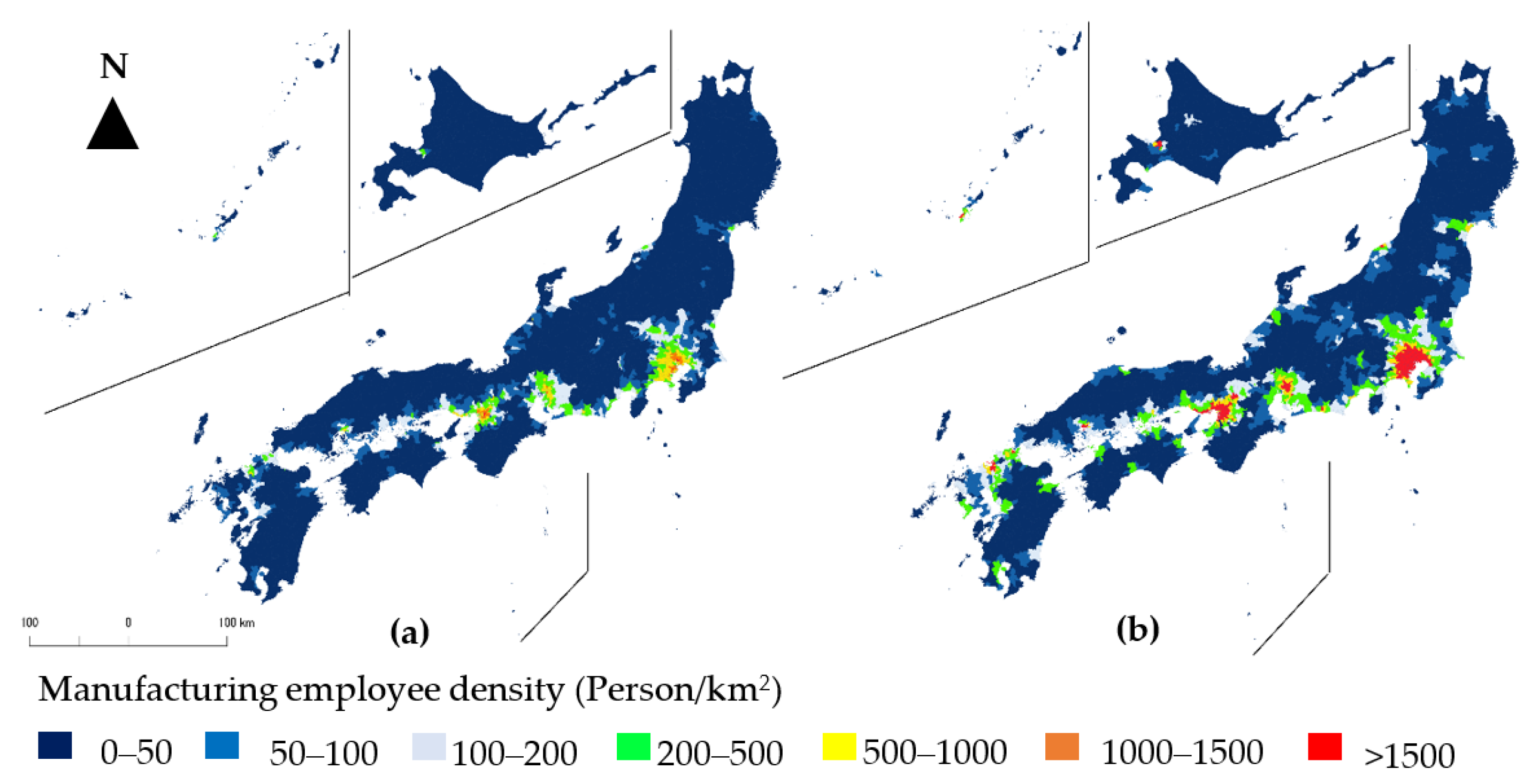

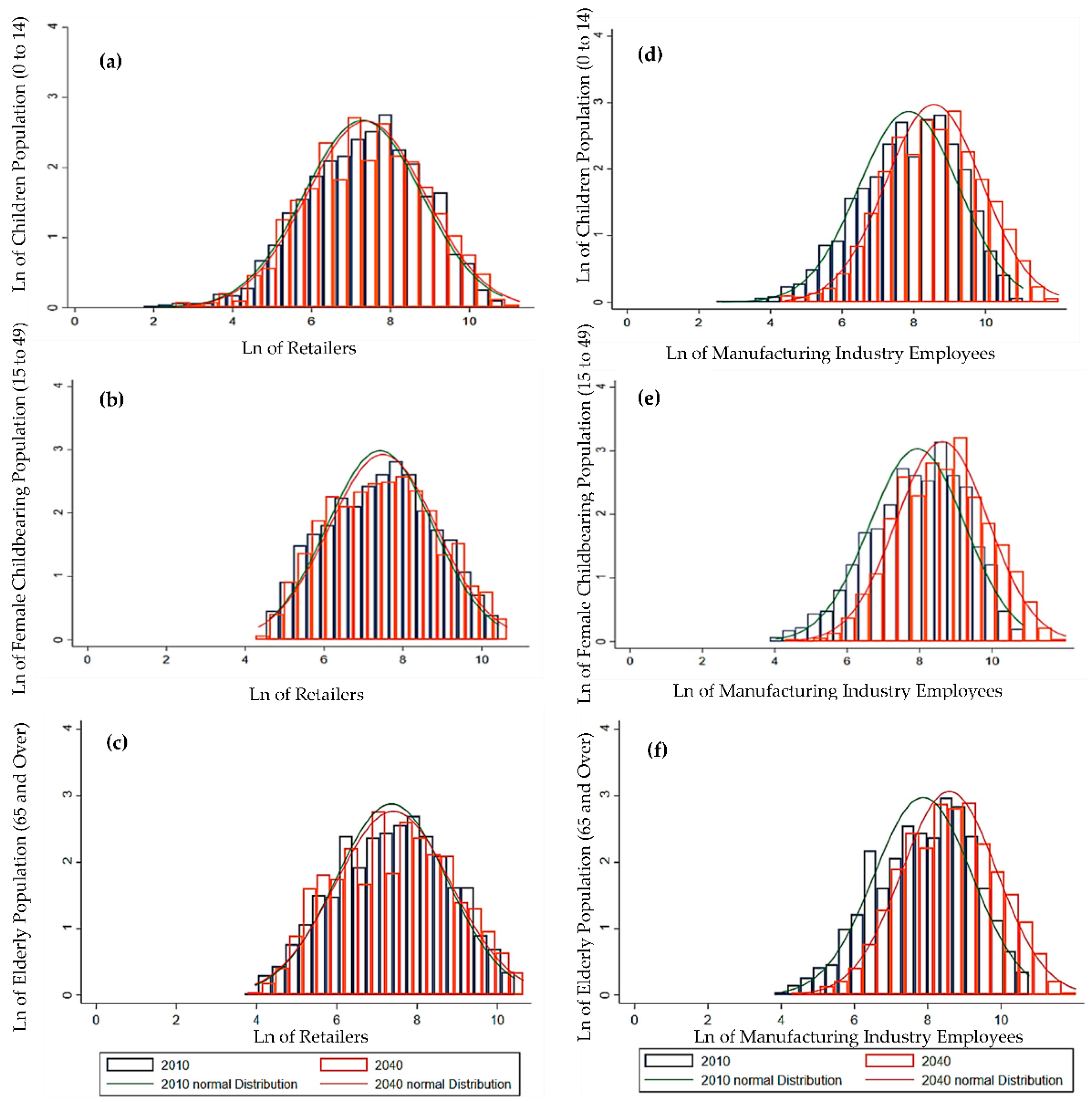

6.2. Distribution of Urbanization Indices: Retailers and Manufacturing Employees

6.3. Transition of Population According to Urbanization Indices

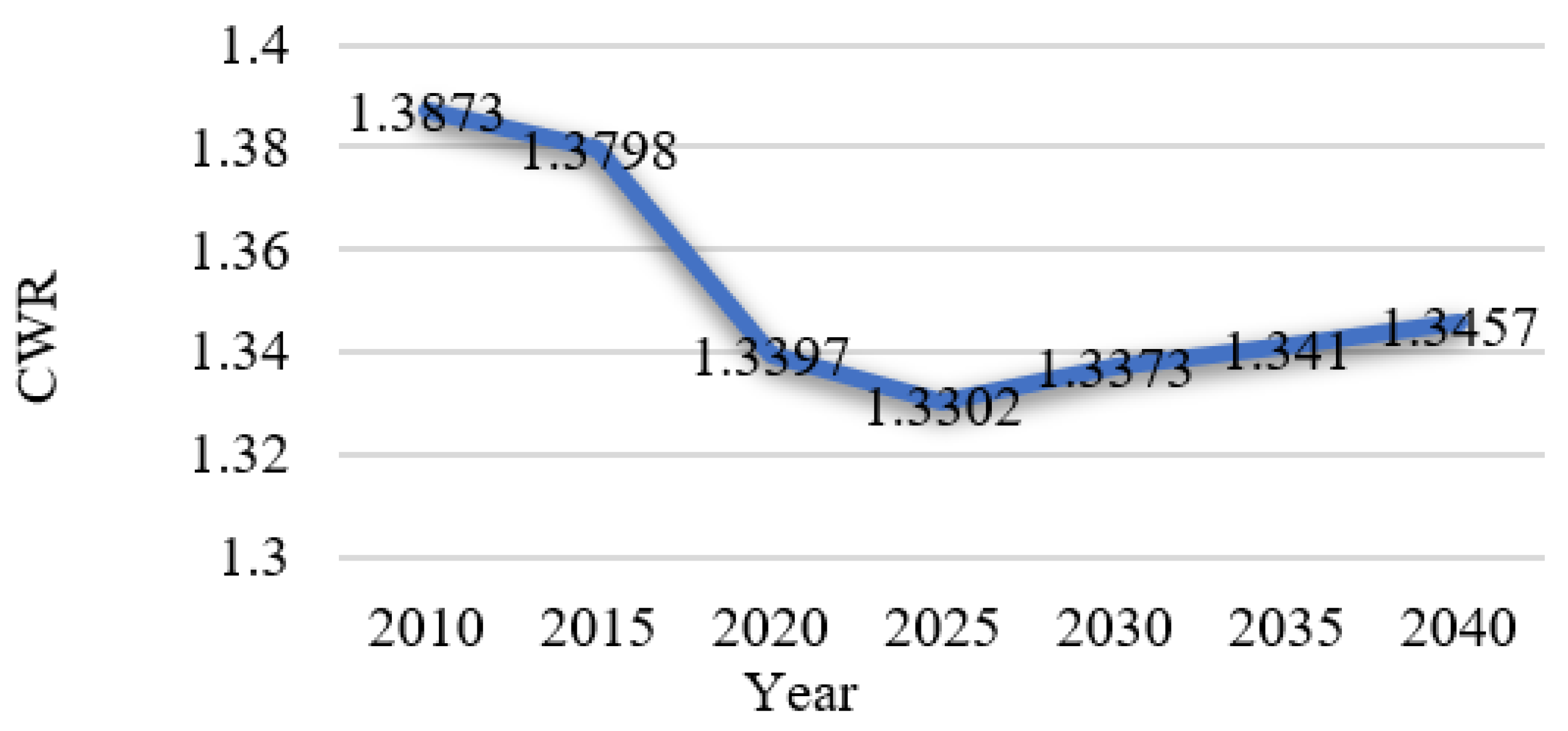

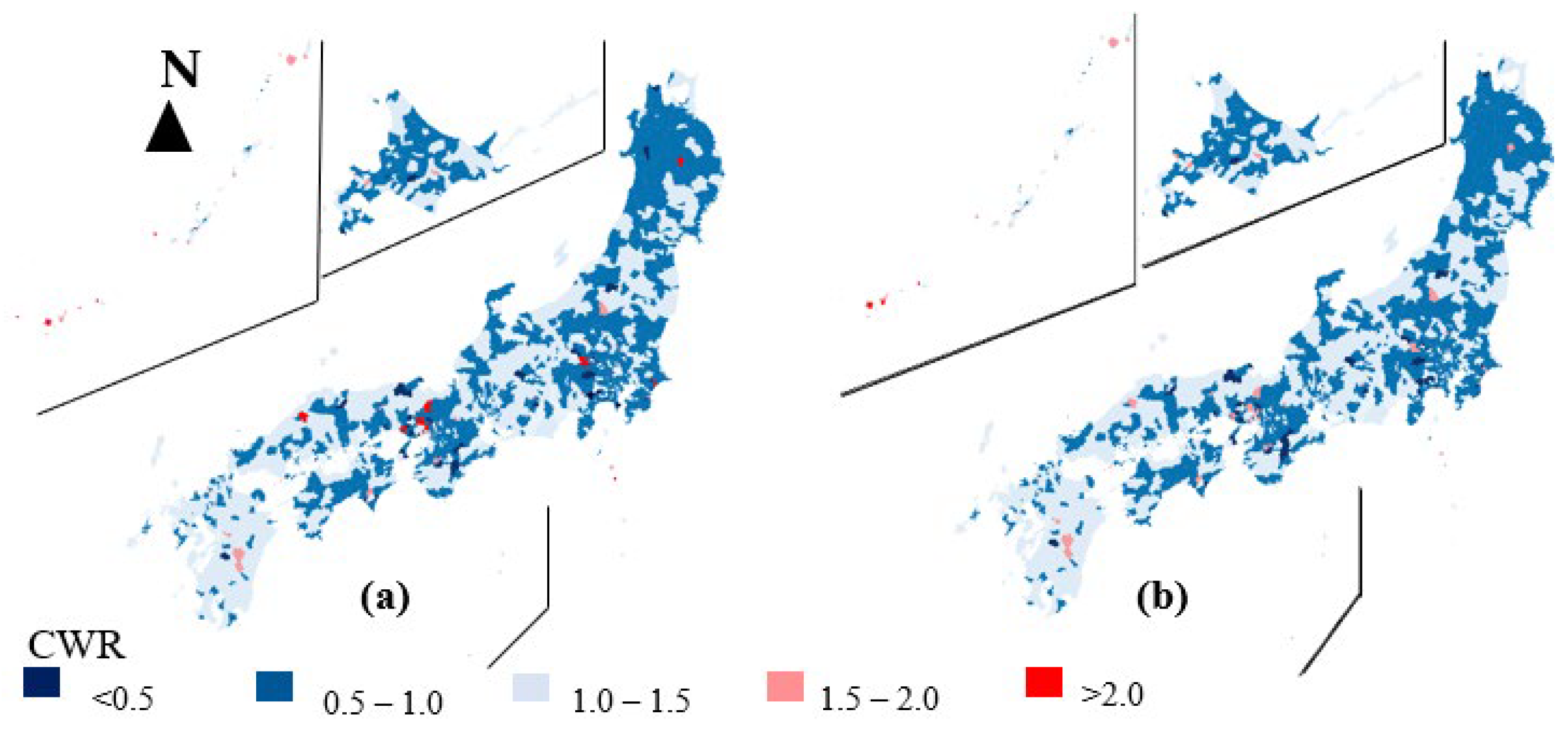

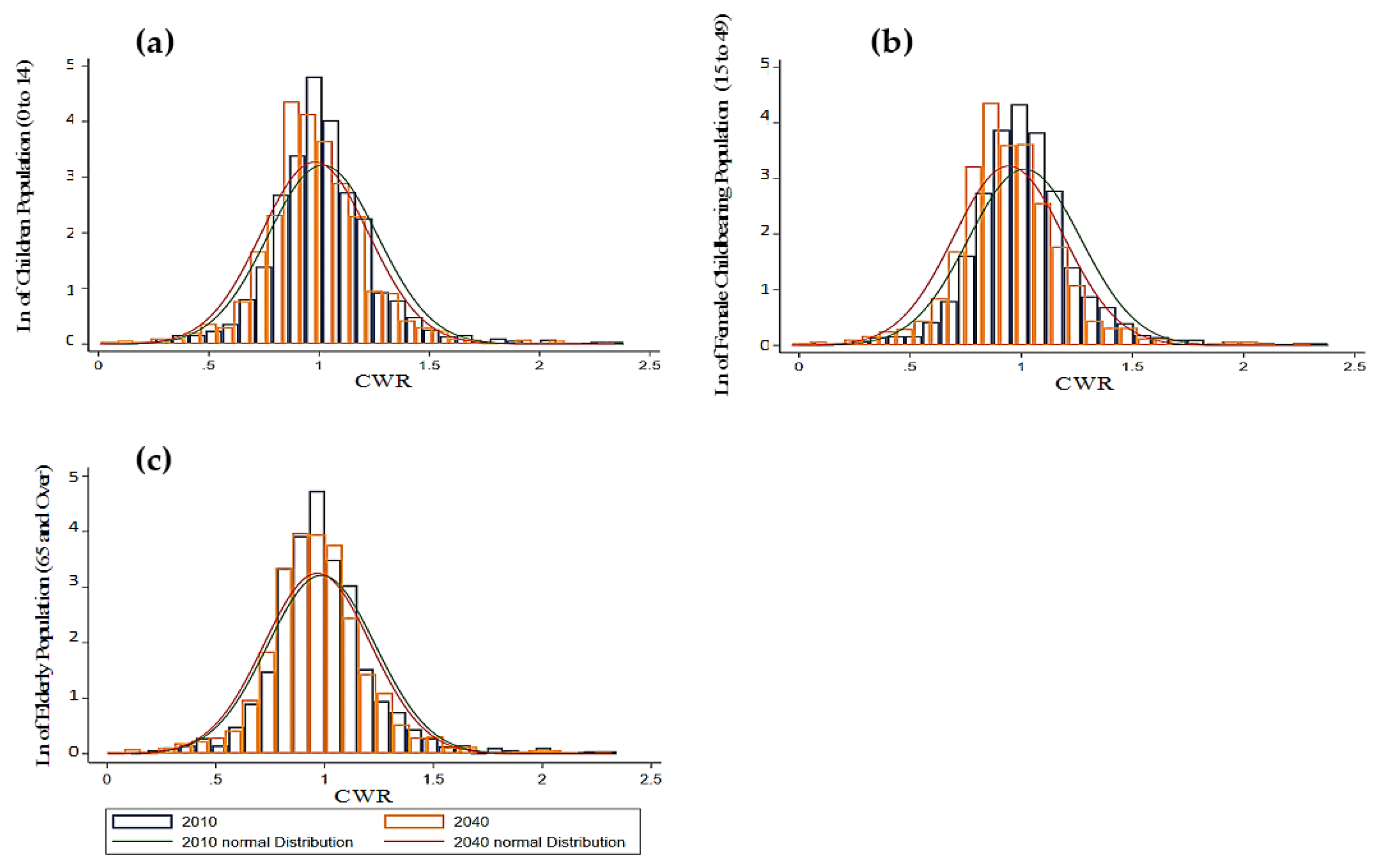

6.4. Population Distribution in Terms of Child–Women Ratio (CWR)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Moran’s I | Expected I | Variance | Z-Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Total Immigration | 0.39692 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00856 | 45.28304 | 0.00000 |

| Male Total Emigration | 0.41763 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00859 | 48.67499 | 0.00000 |

| Female Total Immigration | 0.39061 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00857 | 45.66852 | 0.00000 |

| Female Total Emigration | 0.37421 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00556 | 43.8016 | 0.00000 |

| No: of Employees in 2nd Industry | 0.34752 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00726 | 47.94531 | 0.00000 |

| No: of Retailers | 0.34389 *** | −0.00072 | 0.00726 | 47.44475 | 0.00000 |

| Cohorts | Spatial Correlation Parameter () | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Immigration | Male Emigration | Female Immigration | Female Emigration | |

| 0–4 | 0.196 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.056 |

| 5–9 | 0.0868 * | 0.113 * | 0.121 ** | 0.0949 * |

| 10–14 | 0.0848 * | 0.130 ** | 0.152 ** | 0.0895 |

| 15–19 | 0.157 ** | 0.126 * | 0.11 * | 0.0688 |

| 20–24 | 0.137 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.0693 |

| 25–29 | 0.142 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.185 *** |

| 30–34 | 0.210 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.196 *** |

| 35–39 | 0.209 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.127 *** |

| 40–44 | 0.117 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.144 *** | 0.0693 * |

| 45–49 | 0.0746 * | 0.135 *** | 0.0987 ** | 0.129 *** |

| 50–54 | 0.0599 | 0.146 *** | 0.181 *** | 0.172 *** |

| 55–59 | 0.0748 | 0.111 ** | 0.212 *** | 0.0979 ** |

| 60–64 | 0.0908 * | 0.0913 * | 0.131 *** | 0.0657 |

| 65–69 | 0.173 *** | 0.198 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.176 *** |

| 70–74 | 0.220 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.292 *** | 0.204 *** |

| 75–79 | 0.284 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.101 * |

| 80–84 | 0.349 *** | 0.304 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.0863 |

| 85–89 | 0.284 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.168 *** | 0.0348 |

| 90–over | 0.456 *** | 0.514 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.0934 |

| Total | 0.338 *** | 0.524 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.416 *** |

References

- Lutz, W.; Gailey, N. Depopulation as a Policy Challenge in the Context of Global Demographic Trends. UNDP Serbia. 2020. Available online: http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/16811 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Population Reference Bureau. World Population Data Sheet 2021. Available online: https://interactives.prb.org/2021-wpds (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Chen, L.; Mu, T.; Li, X.; Dong, J. Population Prediction of Chinese Prefecture-Level Cities Based on Multiple Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Rees, P. Recent Developments in Population Projection Methodology. Popul. Space Place 2005, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G. Can Knowledge Improve Population Forecasts at Subcounty Levels? Demography 2009, 46, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.K.; Jeff, T.; David, A.S. Implementing the Cohort-Component Method. In A Practitioner’s Guide to State and Local Population Projections; The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. Evaluation of Alternative Cohort-Component Models for Local Area Population Forecasts. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2016, 35, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoraghein, H.; O’Neill, B.C. US State-level Projections of the Spatial Distribution of Population Consistent with Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifarré i Arolas, H. A Cohort Perspective of the Effect of Unemployment on Fertility. J. Popul. Econ. 2017, 30, 1211–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.J.Q.; Stuart, G. An evaluation of fertility- and migration-based policy responses to japan’s ageing population. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, S.B. An Economic Analysis of Fertility. In Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960; pp. 209–240. Available online: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2387 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Caltabiano, M.; Rosina, A. An Analysis of Late Fertility in Italy: The Role of Education; Atti della Riunione Scientifica della Società Italiana di Statistica; Università degli Studi di Padova: Padova, Italy, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.E.B. Internal Migration in Developing Economies: An Overview; KNOMAD Working Paper No. 6; Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD): Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.; Rowe, F. Internal Migration and Spatial De-Concentration of Population in Latin America. 2018. Available online: https://www.niussp.org/migration-and-foreigners/internal-migration-and-spatial-de-concentration-of-population-in-latin-america/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Lutz, W.; Amran, G.; Bélanger, A.; Conte, A.; Gailey, N.; Ghio, D.; Grapsa, E.; Jensen, K.; Loichinger, E.; Marois, G.; et al. Demographic Scenarios for the EU: Migration, Population and Education; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.E.; Roig, M.; Reuman, D.C.; GoGwilt, C. International Migration beyond Gravity: A Statistical Model for Use in Population Projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15269–15274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, C. A Manifesto for Quantitative Multi-Sited Approaches to International Migration. Int. Migr. Rev. 2014, 48, 921–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, M.; Stephan, L.T. Subnational Population Projections by Age: An Evaluation of Combined Forecast Techniques. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2015, 34, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, N.; Sander, N.; Sulak, H. Internal migration and housing costs—A panel analysis for Germany. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K.; Nagayasu, J. Toward Coexistence of Immigrants and Local People in Japan: Implications from Spatial Assimilation Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Dimitrova, A.; Muttarak, R.; Cuaresma, J.C.; Peisker, J. A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y. Economic Geography, Fertility and Migration. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Chong, K.Y. Fertility and Internal Migration. Fed. Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev. Fourth Quart. 2020, 102, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X. The influence of internal migration on regional innovation in China. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanle, P. Towards an Asia-Pacific depopulation dividend in the 21st century. Regional growth and shrinkage in Japan and New Zealand. Asia-Pac. J. 2017, 15, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Deshingkar, P.; Grimm, S. Internal Migration and Development: A Global Perspective; Paper Prepared for International Organization for Migration (IOM); International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deshingkar, P. Internal Migration, Poverty and Development in Asia; Briefing Paper; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, G.J.; Bijak, J.; Forster, J.J.; Raymer, J.; Smith, P.W.F.; Wong, J.S.T. Integrating Uncertainty in Time Series Population Forecasts: An Illustration Using a Simple Projection Model. Demogr. Res. 2013, 29, 1187–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, R. Cohort Studies: History of the Method, I. Prospective Cohort Studies. Soz. Prav. SPM 2001, 46, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vanella, P.; Descheenie, P. A Probabilistic Cohort-Component Model for Population Forecasting—The Case of Germany. J. Popul. Ageing 2020, 13, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, P.; Martin, B.; Marek, K.; Dorota, K.; Philipp, U.; Aude, B.; Elin, C.-E.; John, S. The Impact of Internal Migration on Population Redistribution: An International Comparison: The Impact of Internal Migration. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, M.; Vérène, W.; Magali, C.; Karine, L.; Aymeric, U.; Pascal, B. Heat and Cold Related-Mortality in 18 French Cities. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, P.R. Demography as a spatial social science. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2007, 26, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.A.; Parker, D.M. Progress in Spatial Demography. Demogr. Res. 2013, 28, 271–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Grossman, I.; Alexander, M.; Rees, P.; Temple, J. Methods for Small Area Population Forecasts: State-of-the-Art and Research Needs. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2021, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, M.; Kéry, M. Combining Information in Hierarchical Models Improves Inferences in Population Ecology and Demographic Population Analyses: Hierarchical Models in Population Ecology. Anim. Conserv. 2012, 15, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.; Robert, K.P. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Wang, D. Small-Area Population Forecasting: A Geographically Weighted Regression Approach. In The Frontiers of Applied Demography; Applied Demography Series; Swanson, D.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Wang, Z.; Choi, S.; Zeng, Y. Forecast Households at the County Level: An Application of the ProFamy Extended Cohort-Component Method in Six Counties of Southern California, 2010 to 2040. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Result of the Population Estimates, 2015 Population Census of Japan; Final Report; Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Tokyo, Japan, 2018.

- Matanle, P.; Sato, Y. Coming Soon to a City Near You! Learning to Live ‘Beyond Growth’ in Japan’s Shrinking Regions. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2010, 13, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Result of the Population Estimates, 2010 Population Census of Japan; Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Tokyo, Japan, 2012; Volume 7-1.

- Chi, G.; Vos, P. Small-area population forecasting: Borrowing strength across space and time. Popul. Space Place 2011, 17, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dorddrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Phipps, T.; Anselin, L. Measuring the benefits of air quality improvement: A spatial hedonic approach. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 45, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Le Gallo, J. Interpolation of Air Quality Measures in Hedonic House Price Models: Spatial Aspects. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2006, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in Japan. Population Projections for Japan. Available online: https://www.ipss.go.jp/index-e.asp (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Oo, S.; Tsukai, M. Internal Migration Prediction for Economic Development in Japan by Considering the Spatial Dependencies. In Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Tokyo, Japan, 25 May 2021; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vollset, S.E.; Goren, E.; Yuan, C.-W.; Cao, J.; Smith, A.E.; Hsiao, T.; Bisignano, C.; Azhar, G.S.; Castro, E.; Chalek, J.; et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 396, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 66,763.36 | 97,183.621 | 178 | 903,346 |

| Net Migration | 29.337 | 1685.814 | −8279 | 68,917 |

| Male Net Migration | 17 | 776.239 | −1044 | 31,822 |

| Male Immigration | 1660 | 8195 | 0 | 337,629 |

| Male Emigration | 2401 | 13,230 | 6 | 547,290 |

| Female Net Migration | 19 | 903.962 | −896 | 37,095 |

| Female Immigration | 1460 | 7506 | 2 | 309,618 |

| Female Emigration | 1387 | 6297 | 6 | 258,300 |

| Working-age Population (15–64) | 27,390 | 46,094.009 | 0 | 573,317 |

| Number of Employees in Secondary Industry | 7426.012 | 9922.661 | 13 | 96,761 |

| Number of Retailers | 10,949.84 | 7716.154 | 4 | 18,670 |

| Initial Year 2010 Population (Person) | Final Predicted Year 2040 Population Using CCA (Person) | Final Predicted Year 2040 Population Using Proposed Approach (Person) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 128,057,352 | 110,923,739 | 109,728,234 |

| 0–4 | 5,322,799 | 3,536,609 | 3,453,977 |

| 5–9 | 5,593,452 | 4,195,635 | 4,112,763 |

| 10–14 | 5,910,750 | 4,205,658 | 4,122,782 |

| 15–19 | 6,160,687 | 4,268,129 | 4,267,003 |

| 20–24 | 6,518,181 | 4,367,966 | 4,363,330 |

| 25–29 | 7,352,494 | 6,561,470 | 6,586,601 |

| 30–34 | 8,358,745 | 6,245,334 | 6,266,845 |

| 35–39 | 9,748,001 | 7,291,696 | 7,325,188 |

| 40–44 | 8,743,156 | 6,542,081 | 6,566,990 |

| 45–49 | 8,038,243 | 5,409,622 | 5,421,565 |

| 50–54 | 7,649,769 | 5,118,017 | 5,126,621 |

| 55–59 | 9,042,016 | 6,214,705 | 6,235,866 |

| 60–64 | 10,372,889 | 7,848,735 | 7,888,604 |

| 65–over | 29,246,170 | 39,118,082 | 37,990,098 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oo, S.; Tsukai, M. Long-Term Impact of Interregional Migrants on Population Prediction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116580

Oo S, Tsukai M. Long-Term Impact of Interregional Migrants on Population Prediction. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116580

Chicago/Turabian StyleOo, Sebal, and Makoto Tsukai. 2022. "Long-Term Impact of Interregional Migrants on Population Prediction" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116580

APA StyleOo, S., & Tsukai, M. (2022). Long-Term Impact of Interregional Migrants on Population Prediction. Sustainability, 14(11), 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116580