Heterogeneity Effect of Corporate Financialization on Total Factor Productivity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

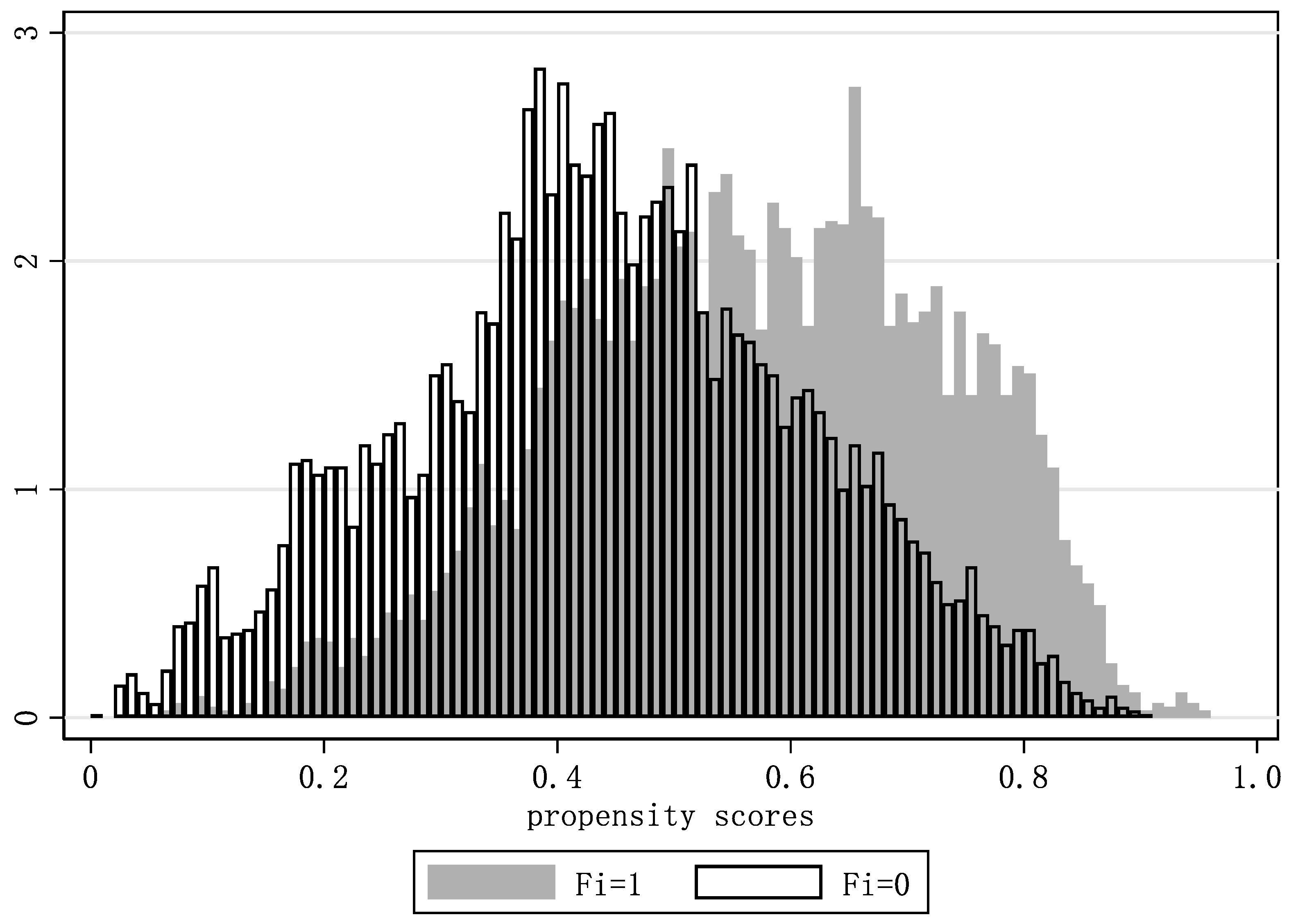

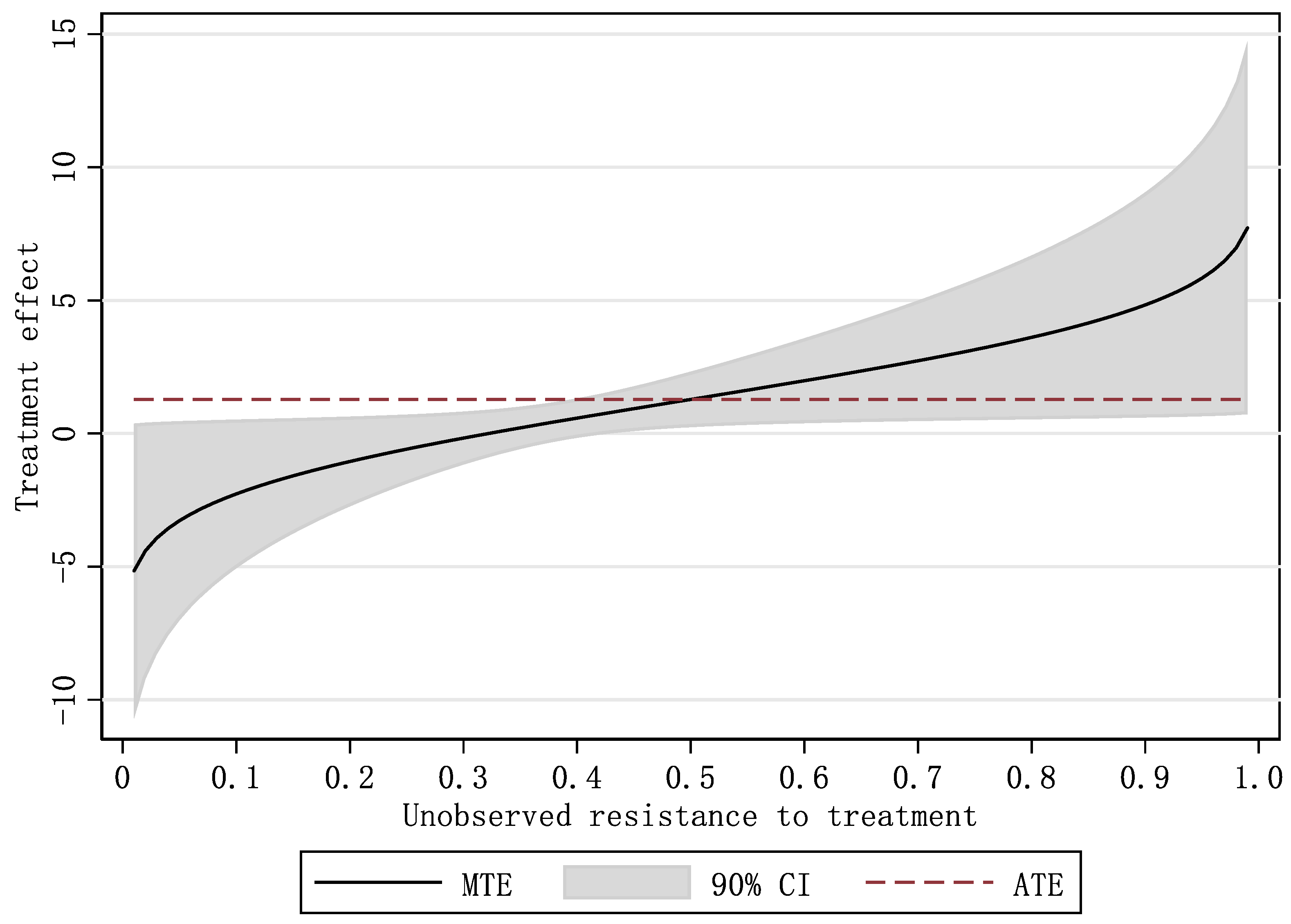

3. Empirical Strategy and Research Design

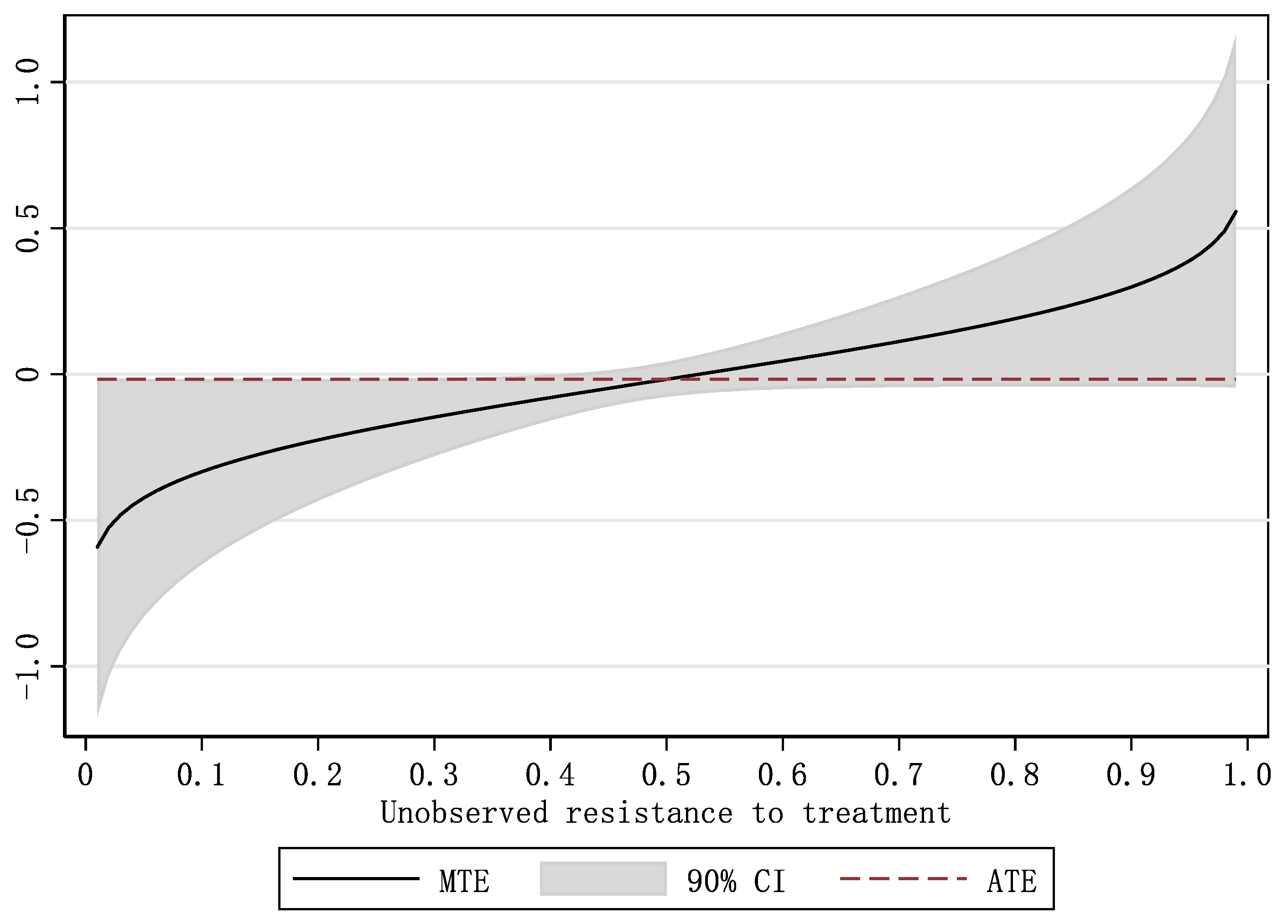

3.1. Framework of Analysis and Definition of Treatment Effects

3.2. Data

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| TFP | LP Method |

| Fi | Fi = 1, if corporate financialization greater than median of industry financialization, otherwise Fi = 0. |

| Size | Logarithm of total assets |

| Cashflow | Logarithm of net cash flows from operating activities |

| Roe | Net profit/total assets |

| Age | Current year—year of establishment of each company |

| Growth | Annual growth rate of operating income |

| Tng | Fixed assets/total assets |

| Lev | Total liabilities/total assets |

| Top | Number of shares held by the largest shareholder/total share capital |

| SA | SA = −0.737 × Size + 0.04 × Size2 − 0.04 × Age |

| Shibor | The shanghai interbank offered rate |

| M2/GDP | M2/GDP |

| R&D | R&D investment/total assets |

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Instrumental Variable Estimates

4.2. Marginal Treatment Effects

4.3. Counterfactual Analysis

4.4. Robust Test

5. Mechanism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sawyer, M. What is financialization? Int. J. Political Econ. 2013, 42, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Sheng, X. Does Corporate Financialization Have a Non-Linear Impact on Sustainable Total Factor Productivity? Perspectives of Cash Holdings and Technical Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Cui, Y.; Chan, K.C. Firm-level financialization: Contributing factor, sources, and economic consequence. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 80, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.C. Financialization and the slowdown in Korean firms’ R&D investment. Asian Econ. Pap. 2012, 11, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Onaran, Ö.; Stockhammer, E.; Grafl, L. The Finance-Dominated Growth Regime, Distribution, and Aggregate Demand in the US. 2009. Available online: https://epub.wu.ac.at/id/eprint/1306 (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D.; Rogerson, R. Policy distortions and aggregate productivity with heterogeneous establishments. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2008, 11, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, F. Financial liberalization, private investment and portfolio choice: Financialization of real sectors in emerging markets. J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 88, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denis, D.J.; Sibilkov, V. Financial constraints, investment, and the value of cash holdings. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehringer, A. Growth, productivity and capital accumulation: The effects of financial liberalization in the case of European integration. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2013, 25, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lu, Y. U-shape relationship between non-currency financial assets and operating profit: Evidence from financialization of Chinese listed non-financial corporates. J. Finan. Res. 2015, 6, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.S.; Zhang, B.T. The mystery of china’s declining industrial investment rate: The financialization of the economy perspective. Econ. Res. 2016, 51, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lazonick, W. Innovative Business Models and Varieties of Capitalism: Financialization of the US Corporation. Bus. Hist. Review 2010, 84, 675–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orhangazi, Ö. Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: A theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003. Camb. J. Econ. 2008, 32, 863–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kai, L.; Prabhala, N.R. Self-selection models in corporate finance. In Handbook of Empirical Corporate Finance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermalin, B.; Weisbach, M.S. Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution: A survey of the economic literature. Econ. Policy Rev. 2001, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, H.; Li, T.; Sun, Y. Board attributes and herding in corporate investment: Evidence from Chinese-listed firms. Eur. J. Financ. 2016, 22, 432–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Z.; Drozdowski, G. Does the Net Present Value as a Financial Metric Fit Investment in Green Energy Security? Energies 2022, 15, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdowski, G. Economic calculus qua an instrument to support sustainable development under increasing risk. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. Energy productivity, labor productivity, and global warming. In Twenty—First Century Macroeconomics: Responding to the Climate Challenge; Edward Elgar: Northhampton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B.J.; Lentz, R.; Mortensen, D.T.; Neumann, G.R.; Werwatz, A. On-the-job search and the wage distribution. J. Labor Econ. 2005, 23, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Männasoo, K.; Hein, H.; Ruubel, R. The contributions of human capital, R&D spending and convergence to total factor productivity growth. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 1598–1611. [Google Scholar]

- Dziekański, P.; Prus, P. Financial diversity and the development process: Case study of rural communes of Eastern Poland in 2009–2018. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.P. Managerial incentives for short-term results: A reply. J. Financ. 1987, 42, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Darnall, N.; Husted, B.W. Sustainability strategy in constrained economic times. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Baek, Y.J.; Kang, S.J. Financialization, Managerial Myopia and Short-termism of Innovation Strategy: The Case of the Korean Firms. Camb. J. Econ. 2020, 44, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Liu, H. Financialization of manufacturing companies and corporate innovation: Lessons from an emerging economy. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xuan, C. A study on the motivation of financialization in emerging markets: The case of Chinese nonfinancial corporations. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 72, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, J. The neoliberal paradox: The impact of destructive product market competition and impatient finance on nonfinancial corporations in the neoliberal era. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2003, 35, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heckman, J.J.; Vytlacil, E.J. The relationship between treatment parameters within a latent variable framework. Econ. Lett. 2000, 66, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Urzua, S.; Vytlacil, E. Understanding instrumental variables in models with essential heterogeneity. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 389–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ackerberg, D.; Hahn, J. Some non-parametric identification results using timing and information set assumptions. 2015; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J. Collateral, debt capacity, and corporate investment: Evidence from a natural experiment. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 85, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrando, A.; Mulier, K. Firms’ financing constraints: Do perceptions match the actual situation? Econ. Soc. Rev. 2015, 46, 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S. Collateral, Reallocation, and Aggregate Productivity: Evidence from the US Housing Boom; University of Zurich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglioli, A. Financial integration, productivity and capital accumulation. J. Int. Econ. 2008, 76, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shan, X.; Duchi, L. An empirical research on the effect of corporate financialization on technological innovation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 40, 240. [Google Scholar]

| Fi = 1 | Fi = 0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Obs | Mean |

| TFP | 7426 | 2.510 | 7500 | 2.562 |

| Houseprice | 7735 | 9.076 | 7966 | 8.932 |

| Cashflow | 8353 | 0.041 | 8606 | 0.038 |

| Size | 8353 | 22.14 | 8606 | 21.91 |

| Lev | 8353 | 0.443 | 8605 | 0.480 |

| Roa | 8353 | 0.029 | 8606 | 0.034 |

| Age | 8353 | 11.47 | 8608 | 9.134 |

| Tng | 8353 | 0.524 | 8605 | 0.472 |

| Top | 8353 | 33.78 | 8608 | 34.75 |

| SA | 8353 | 2.892 | 8606 | 2.758 |

| Growth | 8266 | 0.316 | 8349 | 0.348 |

| Shibor | 8353 | 0.040 | 8608 | 0.040 |

| M2/GDP | 8353 | 0.055 | 8608 | 0.055 |

| R&D | 5043 | 0.039 | 5661 | 0.040 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | Fi | TFP | |

| Houseprice | 0.139 *** | ||

| Fi | (4.46) | ||

| 0.012 | −0.049 | ||

| (0.011) | (−0.32) | ||

| Cashflow | 0.025 | −0.012 | 0.059 |

| (0.050) | (−0.20) | (1.46) | |

| Size | 0.041 *** | −0.004 | 0.039 *** |

| (0.014) | (−0.49) | (6.17) | |

| Lev | −0.129 ** | 0.181 *** | −0.128 ** |

| (0.051) | (3.46) | (−2.75) | |

| Roa | 0.225 *** | −0.061 | 0.210 *** |

| (0.082) | (−0.87) | (4.23) | |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.005 | −0.0003 |

| (0.002) | (−0.07) | (−0.01) | |

| Tng | 0.043 | −0.037 | 0.038 |

| (0.037) | (−0.88) | (1.26) | |

| Top | 0.000 | −0.003 *** | 0.0007 |

| (0.001) | (−4.22) | (1.19) | |

| SA | −2.748 *** | −0.010 | −2.071 *** |

| (0.241) | (0.007) | (0.105) | |

| Growth | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.005 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.005) | |

| Shibor | −2.772 | −6.801 | 1.359 |

| (9.288) | (−0.03) | (0.01) | |

| M2/GDP | −2.892 | −0.983 | −2.095 * |

| (1.943) | (−0.70) | (−2.18) | |

| Constant | 2.073 *** | - | - |

| (0.321) | |||

| Cragg-Donald-F | 19.86 | ||

| IndustryFE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CityFE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 13,660 | 12,732 | 12,732 |

| R-squared | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | β0 | β1 − β0 | k | effect |

| Cashflow | −0.492 ** | 1.521 *** | ||

| (0.247) | (0.453) | |||

| Roa | 0.906 *** | −1.138 * | ||

| (0.325) | (0.582) | |||

| Age | 0.034 * | −0.102 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.034) | |||

| Tng | 0.106 | 2.060 *** | ||

| (0.126) | (0.305) | |||

| mills | 2.590 * | |||

| (1.512) | ||||

| ATE | 0.239 | |||

| (0.381) | ||||

| ATT | −1.620 | |||

| (1.232) | ||||

| ATU | 2.136 * | |||

| (1.210) | ||||

| LATE | 1.798 ** | |||

| (0.814) | ||||

| mprte1 | 0.289 | |||

| (0.367) | ||||

| mprte2 | 0.265 | |||

| (0.380) | ||||

| mprte3 | 0.718 | |||

| (0.455) | ||||

| _cons | -- | −9.607 | ||

| -- | (15.330) | |||

| CityFE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Observations | 12,483 | 12,483 |

| Counterfactuals | PRTE |

|---|---|

| housing prices of tier one decrease by 40% | −0.157 (0.374) |

| housing prices of tiers two & three decrease by 40% | 0.453 (0.377) |

| housing prices of tier one decrease by 40%; housing prices of tiers two & three increase by 40% | 0.695 * (0.392) |

| Variable | (1) Fi | (2) R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Houseprice | 0.146 *** | |

| (0.037) | ||

| Fi | −0.049 ** | |

| (−0.237) | ||

| Cragg-Donald-F | 15.36 | |

| IndustryFE | Yes | Yes |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes |

| CityFE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 9352 | 9352 |

| R-squared | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| ATE | −0.017 (0.036) |

| ATT | −0.215 * (0.120) |

| ATU | 0.164 (0.165) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Xu, S. Heterogeneity Effect of Corporate Financialization on Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116577

Wang H, Xu S. Heterogeneity Effect of Corporate Financialization on Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116577

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hui, and Shu Xu. 2022. "Heterogeneity Effect of Corporate Financialization on Total Factor Productivity" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116577

APA StyleWang, H., & Xu, S. (2022). Heterogeneity Effect of Corporate Financialization on Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability, 14(11), 6577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116577