Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

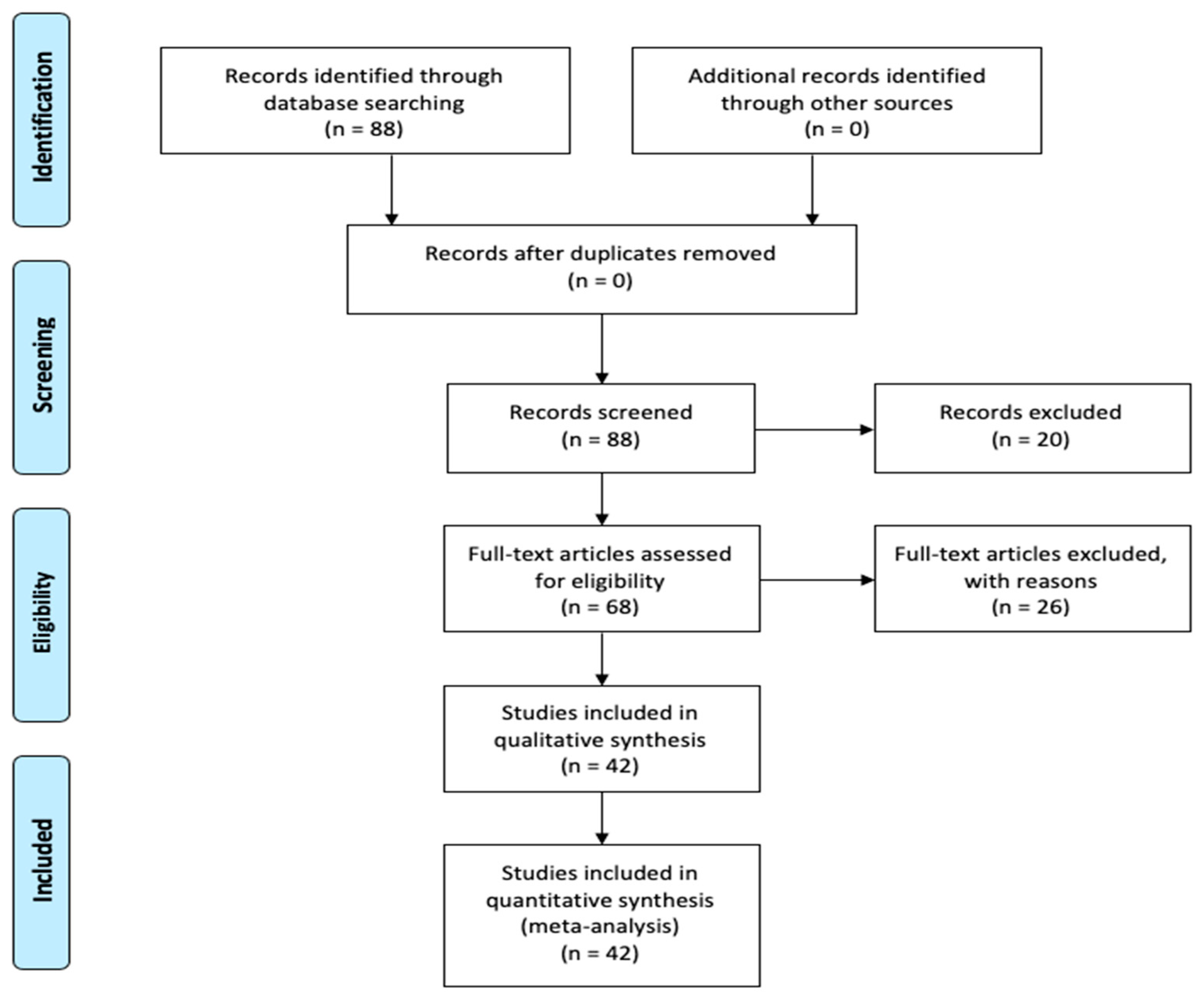

2. Methodology

- Inclusion criteria:

- ○

- Peer-reviewed papers published from 2000 to June 2020;

- ○

- Research papers in English;

- ○

- Research papers published in journals with journal impact factor;

- ○

- Theoretical, qualitative, or quantitative papers.

- Exclusion criteria:

- ○

- Peer-reviewed papers published after June 2020;

- ○

- Peer-reviewed books, chapters, conference papers or working papers;

- ○

- Research papers published in journals without WoS impact factor;

- ○

- Research papers unrelated to the SLR topic;

- ○

- Research papers published in journals included in the Emerging Sources Citation Index.

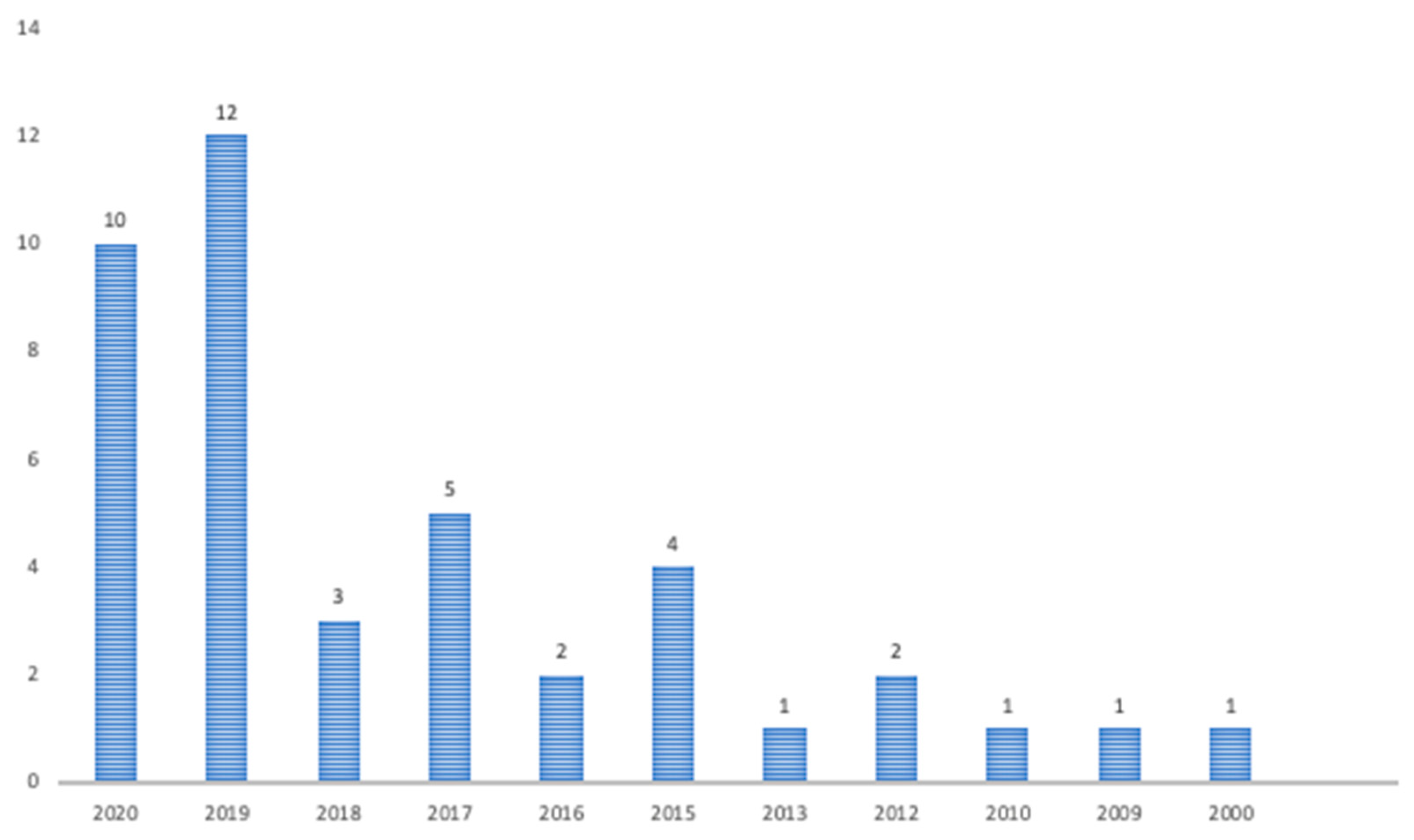

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Batres, L.A.; Doh, J.P.; Miller, V.V.; Pisani, M.J. Stakeholder pressures as determinants of CSR strategic choice: Why do firms choose symbolic versus substantive self-regulatory codes of conduct? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Tripple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, P.; Stokes, P.; Cooper, S.C.; Liu, Y.; Moore, N.; Britzelmaier, B.; Tarba, S. Cultural Antecedents of Sustainability and Regional Economic Development—A Study of SME ‘Mittelstand’ Firms in Baden-Württemberg (Germany). Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starik, M.; Marcus, A.A. Introduction to the Special Research Forum on the Management of Organizations in the Natural Environment: A Field Emerging from Multiple Paths. With Many Challenges Ahead. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Abhayawansa, S.; Adams, C.A.; Neesham, C. Accountability and governance in pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals: Conceptualising how governments create value. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.D.C.V.; Martín-Cervantes, P.A.; del Mar Miralles-Quirós, M. Sustainable development and the limits of gender policies on corporate boards in Europe. A comparative analysis between developed and emerging markets. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Sakundarini, N.; Raja Ghazilla, R.A.; Thurasamy, R. The impact of sustainable manufacturing practices on sustainability performance: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 2, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.B.; Pedrozo, E.A.; Estivalete, V.F.B. Towards sustainable development strategies: A complex view following the contribution of Edgar Morin. Manag. Dec. 2006, 44, 871–891. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, V.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Mani, K.T. Supply chain social sustainability in small and medium manufacturing enterprises and firms’ performance: Empirical evidence from an emerging Asian economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future, World Commission on Environment and Development; University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning Sustainability Three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability: Are We There Yet? Org. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Business Contribution to Sustainable Development. 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52002DC0347&from=EN (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Wolf, J. The relationship between sustainable supply chain management, stakeholder pressure and corporate sustainability performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The New European Consensus on Development—EU and Member States Sign Joint Strategy to Eradicate Poverty. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1503 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Kaplan, S. Why social responsibility produces more resilient organizations. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.C.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.H.; Yuan, X. Can corporate social responsibility protect firm value during the COVID-19 pandemic? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Shared Responsibility, Global Solidarity: Responding to the Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/SG-Report-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Covid19.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D. The influence of technology innovation on SME performance through environmental sustainability practices in Kenya. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Misra, M. Linking corporate social responsibility (CSR) and organizational performance: The moderating effect of corporate reputation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-D.P. A Review of the Theories of Corporate Social Responsibility: Its Evolutionary Path and the Road Ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Corporate Social Responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westman, L.; Luederitz, C.; Kundurpi, A.; Mercado, A.J.; Weber, O.; Burch, S.L. Conceptualizing businesses as social actors: A framework for understanding sustainability actions in small-and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Hurtado-Torres, N.; Sharma, S.; García-Morals, V.J. Environmental Strategy and Performance in Small Firms: A Resource-based Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, F.; Caputo, A.; Soverchia, M. Sustainability and financial performance of small and medium sized enterprises: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornilaki, M.; Thomas, R.; Font, X. The sustainability behaviour of small firms in tourism: The role of self-efficacy and contextual constraints. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, E.S.; Martens, M.L.; Cho, C.H. Engaging small-and medium-sized businesses in sustainability. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2010, 1, 178–200. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, L.J. Small Business Social Responsibility: Expanding Core CSR Theory. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, C.; Scherer, A.G.; Spence, L.J. Walking and Talking Corporate Social Responsibility: Implications of Firm Size and Organizational Cost. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1169–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. User Guide to the SME Definition; Enterprise and Industry Publications; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/conferences/state-aid/sme/smedefinitionguide_en.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Koirala, S. SMEs: Key Drivers of Green and Inclusive Growth; OECD Green Growth Papers. No. 2019/03; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Local Strength, Global Reach. OECD Policy Rev.: 2000. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/1918307.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- European Commission. Commission recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L124/36, 1–6. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32003H0361 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Moore, S.B.; Manring, S.L. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zou, F.; Zhang, P. The role of innovation for performance improvement through corporate social responsibility practices among small and medium-sized suppliers in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Erdin, C.; Ozkaya, G. Contribution of small and medium enterprises to economic development and quality of life in Turkey. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Annual Report on European SMEs 2018/2019—Research and Development and Innovation by SMEs. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b6a34664-335d-11ea-ba6e-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Gourinchas, P.O.; Penciakova, V.; Sander, N. COVID-19 and SME Failures; IMF Work. No. 2020/207; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Annual Report on European SMEs 2016/2017—Focus on Self-Employment. 2017. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0b7b64b6-ca80-11e7-8e69-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Juergensen, J.; Guimón, J.; Narula, R. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Rangarajan, K.; Dutta, G. Corporate sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises: A literature analysis and road ahead. J. Ind. Bus. Res. 2020, 12, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upstill-Goddard, J.; Glass, J.; Dainty, A.; Nicholson, I. Implementing sustainability in small and medium-sized construction firms. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2016, 23, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kundurpi, A.; Westman, L.; Luederitz, C.; Burch, S.; Mercado, A. Navigating between adaptation and transformation: How intermediaries support businesses in sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 125366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. CSR and Small Business in a European Policy Context: The Five “C”s of CSR and Small Business Research Agenda 2007. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Russo, A.; Tencati, A. CSR strategies of SMEs and large firms. Evidence from Italy. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, J.; Siu, M.; Orengo, A.; Kasiri, N. An analysis of environmental sustainability in small & medium-sized enterprises: Patterns and trends. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, H.; Megicks, P.; Agarwal, S.; Leenders, M.A.A.M. Firm resources and the development of environmental sustainability among small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from the Australian wine industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Kumar, S.; Chavan, M.; Lim, W.M. A systematic literature review on SME financing: Trends and future directions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. Does Size Matter? the State of the Art in Small Business Ethics. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 1999, 8, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero, I.; Javier Sese, F. Management for sustainable development and its impact on firm value in the SME context: Does size matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 985–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.P.; Del Rio Gonzalez, P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J. Drivers and barriers of eco-innovation types for sustainable transitions: A quantitative perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, J.; Gerdt, S.O.; Schewe, G. Determinants of sustainable behavior of firms and the consequences for customer satisfaction in hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L.; Perschke, J. Slipstreaming the larger boats: Social responsibility in medium-sized businesses. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, E.M.; Habisch, A.; Pechlaner, H. Values that create value: Socially responsible business practices in SMEs–empirical evidence from German companies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. Conceptualising the contemporary corporate value creation process. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 906–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cassely, L.; Larbi, S.B.; Revelli, C.; Lacroux, A. Corporate social performance (CSP) in time of economic crisis. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 913–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business models for sustainability: A co-evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Hassan, A.; Harrison, C.; Tarbert, H. CSR reporting: A review of research and agenda for future research. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1395–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Al-Sultan, K.; De Massis, A. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Block, J. Reviewing systematic literature reviews: Ten key questions and criteria for reviewers. Manag. Rev. Quart. 2021, 71, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanasak, P.; Anantana, T.; Paphawasit, B.; Wudhikarn, R. Critical Factors and Performance Measurement of Business Incubators: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, T.; Rasool, G.; Gencel, C. A systematic literature review on software measurement programs. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2016, 73, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, C.; Block, J. Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag. Rev. Quart. 2018, 68, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul-Hus, A.; Desrochers, N.; Costas, R. Characterization, description, and considerations for the use of funding acknowledgement data in Web of Science. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vicente-Saez, R.; Martinez-Fuentes, C. Open Science now: A systematic literature review for an integrated definition. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocconcelli, R.; Cioppi, M.; Fortezza, F.; Francioni, B.; Pagano, A.; Savelli, E.; Splendiani, S. SMEs and marketing: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinicke, A. Performance measurement systems in small and medium-sized enterprises and family firms: A systematic literature review. J. Manag. Control 2018, 28, 457–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Avram, D.; Domnanovich, J.; Kronenberg, C.; Scholz, M. Exploring the integration of corporate social responsibility into the strategies of small-and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J.; Shook, C.L. The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategy Manag. J. 1996, 17, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornilaki, M.; Font, X. Normative influences: How socio-cultural and industrial norms influence the adoption of sustainability practices. A grounded theory of Cretan, small tourism firms. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roxas, B.; Ashill, N.; Chadee, D. Effects of entrepreneurial and environmental sustainability orientations on firm performance: A study of small businesses in the Philippines. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Nybakk, E.; Pinkse, J.; Hansen, E. Being good when not doing well: Examining the effect of the economic downturn on small manufacturing firms’ ongoing sustainability-oriented initiatives. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roxas, B.; Coetzer, A. Institutional environment, managerial attitudes and environmental sustainability orientation of small firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Salisu, I.; Aslam, H.D.; Iqbal, J.; Hameed, I. Resource and Information Access for SME Sustainability in the Era of IR 4.0: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Innovation Capability and Management Commitment. Processes 2019, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caputo, F.; Carrubbo, L.; Sarno, D. The Influence of Cognitive Dimensions on the Consumer-SME Relationship: A Sustainability-Oriented. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhary, S.; Nayak, R.; Dora, M.; Mishra, N.; Ghadge, A. An integrated lean and green approach for improving sustainability performance: A case study of a packaging manufacturing SME in the UK. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, K.H.; Theyel, G.; Wood, C.H. Identifying firm capabilities as drivers of environmental management and sustainability practices–evidence from small and medium-sized manufacturers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, F.; Fuller, T. Foresighting methods and their role in researching small firms and sustainability. Futures 2000, 32, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, F.; Naradda Gamage, S.K.; Hannoon, A. The causal relationship between SME sustainability and banks’ risk. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraži. 2019, 32, 2743–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J. Grazing, exploring and networking for sustainability-oriented innovations in learning-action networks: An SME perspective. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 30, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, J.; Wolfram Cox, J.; Curtis, J.; Kirk-Brown, A.; Walker, B. Beyond business as usual: How (and why) the habit discontinuity hypothesis can inform SME engagement in environmental sustainability practices. Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yus Kelana, B.W.; Abu Mansor, N.N.; Ayyub Hassan, M. Does Sustainability Practices of Human Resources as a New Approach Able to Increase the Workers Productivity in the SME Sector Through Human Resources Policy Support? Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Budhwar, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Cheffi, W. Circular economy to enhance sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2145–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartey, S.H.; Oguntoye, O. Promoting corporate sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises: Key determinants of intermediary performance in Africa. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Chowdhury, S.A.; Abdelaziz, F.B. The impact of lean management practices and sustainably-oriented innovation on sustainability performance of small and medium-sized enterprises: Empirical evidence from the UK. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Chowdhury, S.; Abdelaziz, F.B. Could lean practices and process innovation enhance supply chain sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.Y.; Cheng, Y.T. Analysis model of the sustainability development of manufacturing small and medium-sized enterprises in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesios, C.; Skouloudis, A.; Dey, P.K.; Abdelaziz, F.B.; Kantartzis, A.; Evangelinos, K. Impact of small-and medium-sized enterprises sustainability practices and performance on economic growth from a managerial perspective: Modeling considerations and empirical analysis results. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, F.C.; Zanini, R.R.; Korzenowski, A.L.; Schmidt Junior, R.; Xavier do Nascimento, K.B. Evaluation of sustainability practices in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises in Southern Brazil. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boso, N.; Danso, A.; Leonidou, C.; Uddin, M.; Adeola, O.; Hultman, M. Does financial resource slack drive sustainability expenditure in developing economy small and medium-sized enterprises? J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, S.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Cramer, J.M. Exploring corporate sustainability integration into business activities. Experiences from 18 small and medium sized enterprises in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viesi, D.; Pozzar, F.; Federici, A.; Crema, L.; Mahbub, M.S. Energy efficiency and sustainability assessment of about 500 small and medium-sized enterprises in Central Europe region. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Knowledge acquisition and development in sustainability-oriented small and medium-sized enterprises: Exploring the practices, capabilities and cooperation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3769–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J.; Modig, F.; Hed Vall, G. Commitment to sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises: The influence of strategic orientations and management values. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, J.Y. Development of a framework for the integration and management of sustainability for small-and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 30, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomšič, N.; Bojnec, Š.; Simčič, B. Corporate sustainability and economic performance in small and medium sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Sustainability management and small and medium-sized enterprises: Managers’ awareness and implementation of innovative tools. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Schaefer, A. Small and medium-sized enterprises and sustainability: Managers’ values and engagement with environmental and climate change issues. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broccardo, L.; Zicari, A. Sustainability as a driver for value creation: A business model analysis of small and medium enterprises in the Italian wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefhaber, E.; Pavlovich, K.; Spraul, K. Sustainability-Related Identities and the Institutional Environment: The Case of New Zealand Owner–Managers of Small-and Medium-Sized Hospitality Businesses. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Economic Situation Prospects 2020; United Nations publication: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Demand for Manufacturing: Driving Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development. Industrial Development Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.unido.org/resources-publications-flagship-publications-industrial-development-report-series/industrial-development-report-2018 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Roberts, L.; Hassan, A.; Elamer, A.; Nandy, M. Biodiversity and extinction accounting for sustainable development: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.M.; Ehrenberg, A.S. The design of replicated studies. Am. Stat. 1993, 47, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive Oil mills. Adm. Sci. Quart. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prencipe, A.; Bar-Yosef, S.; Dekker, H.C. Accounting research in family firms: Theoretical and empirical challenges. Eur. Account. Rev. 2014, 23, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, M.C.; Beretta, V. Intellectual capital and SMEs’ performance: A structured literature review. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 288–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudhikarn, R.; Pongpatcharatorntep, D. An Improved Intellectual Capital Management Method for Selecting and Prioritizing Intangible-Related Aspects: A Case Study of Small Enterprise in Thailand. Mathematics 2022, 10, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D.; Sassen, R.; Fischer, J. What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 154–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Cho, C.H. Current trends within social and environmental accounting research: A literature review. Account. Perspect. 2018, 17, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Paper Characteristics | Research Purpose(s) | Theoretical Framework | Paper Type/Method | Organization Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Country | |||||

| Chege and Wang [22] | 2020 | Kenya | To examine the role of technology innovation on SME performance through environmental sustainability practices. | Contingency theory | Research paper/semi-structured questionnaires | Agribusiness firms |

| Knight et al. [52] | 2019 | Australia | To explore the role of firm resources for environmental behavior and disclosure and the role of management attitudes and norms in moderating this relationship. | Resource-based view | Research paper/ questionnaire | Wine industry |

| Kornilaki and Font [79] | 2019 | Greece | To explore how socio-cultural and industrial norms influence the intentions and behaviors towards sustainability of owner-managers. | ---- | Research paper/unstructured interviews | Tourism industry |

| Kornilaki et al. [30] | 2019 | Greece | To understand the factors that influence owner-managers’ evaluations and judgments of self-efficacy to act more sustainably. | ---- | Research paper/unstructured interviews | Tourism industry |

| Kraus et al. [3] | 2020 | Germany | To identify the antecedents and factors which drive SME owner-manager behavior in relation to sustainability and regional/local economic dynamics. | ---- | Research paper/semi-structured interviews | Manufacturing firms |

| Mani et al. [9] | 2020 | India | To explore the different supply chain social sustainability practices, and to investigate how SMEs supply chain social sustainability practices might relate to supply chain performance. | Stakeholder resource-based view | Research paper/semi-structured interviews and structured questionnaires | Manufacturing firms |

| Roxas et al. [80] | 2017 | Philippines | To investigate the effects of entrepreneurial orientation on environmental sustainability orientation and the consequent effects on the performance of SMEs. | Resource-based view | Research paper/questionnaires and interviews | Manufacturing firms |

| Panwar et al. [81] | 2015 | United States of America (USA) | To examine the effects of a decline in SMEs’ financial resources on its ongoing sustainability initiatives. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires | Manufacturing firms |

| Roxas and Coetzer [82] | 2012 | Philippines | To examine how firm’s institutional environment influences its proclivity to adopt a proactive orientation toward environmental sustainability. | Institutional theory | Research paper/questionnaires | Food-processing sector |

| Loucks et al. [31] | 2010 | ---- | To explore how to meaningfully engage SMEs in strategies that improve the social and environmental sustainability of their businesses. | Stakeholder theory | Conceptual paper | SME sector in general |

| Imran et al. [83] | 2019 | Pakistan | To examine how information accessibility and resource availability affect the sustainability of SMEs through the mediation and moderating role of innovation capability and management commitment, respectively. | Natural resource-based view | Research paper/questionnaires | SME sector in general |

| Caputo et al. [84] | 2018 | Italy | To identify the relationships between firms’ sustainability actions and the economic performance of SMEs. | Consumer culture theory | Research paper/structured questionnaire and interviews | Service, Industry, Manufacturing, Transport, others |

| Choudhary et al. [85] | 2019 | United Kingdom (UK) | To measure both operational efficiency and environmental performance of the production system by using the green integrated value stream mapping, and to identify improvement opportunities for minimizing lean and green wastes. | ---- | Research paper/case study with focus group | Packaging-manufacturing SME |

| Upstill-Goddard et al. [47] | 2016 | UK | To examine how capacity for learning can affect the success of implementing sustainability standards. | ---- | Research paper/case studies with semi-structured interviews, participatory meetings, and observation | Construction product manufacturing firms |

| Hofmann et al. [86] | 2012 | USA | To explore the influence of the adoption of advanced technology, collaboration experience with suppliers and customers, and innovative capacity on firms’ ability to implement environmental management practices and environmental collaboration. | Dynamic capabilities perspective | Research paper/interviews and structured questionnaire | Manufacturing firms |

| Tilley and Fuller [87] | 2000 | ---- | To report on the analysis underpinning research exploring the relationship between SMEs and sustainability using fore sighting methods. | ---- | Conceptual paper | SME sector in general |

| Shihadeh et al. [88] | 2019 | Palestine | To examine the influence of banks’ credit to SMEs on non-performing loans. | ---- | Research paper | SME sector in general |

| Klewitz [89] | 2017 | Germany | To explore how the interaction between SMEs and their knowledge network can condition their strategic orientation for sustainability-oriented innovations. | ---- | Research paper/case studies with questionnaire, interviews, participatory observation | SME sector in general |

| Redmond et al. [90] | 2016 | Australia | To show how the relationship between discontinuities, SME owner-manager’s habits, and organisational routines and readiness may influence environmental practices. | ---- | Conceptual paper with interview-based application | SME sector in general |

| Yus Kelana et al. [91] | 2015 | ---- | To explore whether the approach of sustainability practices in the Gollan model can address human resource issues without affecting short-term and long-term profitability of the organization. | ---- | Conceptual paper | SME sector in general |

| Dey, Malesios, De, Budhwar et al. [92] | 2020 | UK | To explore how circular economy fields of action are related to sustainability performance; to identify the issues, challenges, and opportunities of adopting a circular economy; to identify key strategies, resources, and competences that facilitate effective implementation of a circular economy. | ---- | Research paper/case studies with questionnaire, interviews, and focus group | Manufacturing firms |

| Quartey and Oguntoye [93] | 2020 | South Africa; Kenya; Uganda; Ghana. | To explore the key determinants of intermediary performance in promoting corporate sustainability in SMEs. | Organisational performance theory | Research paper/interviews | SME sector in general |

| Bakos et al. [51] | 2020 | ---- | To investigate the trends in drivers and barriers of sustainability adoption and to inform both SMEs managers and policymakers. | ---- | Literature review | SME sector in general |

| Dey, Malesios, De, Chowdhury et al. [94] | 2020 | UK | To explore how lean management practices, sustainability-oriented innovation, corporate social responsibility practices, sustainability and economic performance are correlated. | Complementarity theory | Research paper/questionnaires and interviews | Manufacturing firms |

| Bartolacci et al. [29] | 2020 | ---- | To present a comprehensive knowledge map of the intellectual structure of the field of study of sustainability and financial performances in SMEs. | --- | Literature review | SME sector in general |

| Westman et al. [27] | 2019 | Canada | To examine the underlying drivers of sustainability-oriented actions of SMEs. | Social actor framework | Research paper/questionnaires and semi structured interviews | SME sector in general |

| Dey et al. [95] | 2019 | UK | To examine the effect of sustainability practices, lean practices, and process innovation on sustainability performance, and the mediating effect of lean practices and process innovation separately between sustainability practices and performance. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires and interviews | Manufacturing firms |

| Chang and Cheng [96] | 2019 | Taiwan | To develop an integrated multi-attribute decision analysis model to evaluate the sustainability development of SMEs. | Grey relational theory and rough set theory | Research paper/ questionnaires | Manufacturing firms |

| Malesios et al. [97] | 2018 | UK; France; India | To assess the relationship between the sustainability and the financial performance of SMEs in economic development. | Research paper/questionnaires and interviews | Manufacturing/processing firms | |

| Schmidt et al. [98] | 2018 | Brazil | To analyze the performance of SMEs aiming to identify the main practices of sustainability. | ---- | Research paper/case study with questionnaires and interviews | Manufacturing firms |

| Boso et al. [99] | 2017 | Nigeria | To explore how financial resource slack drives sustainability expenditure under varying conditions of market pressure and political connectedness in a developing-economy market. | Stakeholder theory and slack resource theory | Research paper/interviews | SME sector in general |

| Witjes et al. [100] | 2017 | Netherlands | To understand how SMEs integrate corporate sustainability into their business activities. | ---- | Research paper/case studies | SME sector in general |

| Viesi et al. [101] | 2017 | Austria; Czech Republic; Hungary; Italy; Slovenia | To assess SMEs eco-energy performance, and future and innovation perspectives. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires | SME sector in general |

| Johnson [102] | 2017 | Germany | To investigate the ability of sustainability-oriented SMEs to acquire and develop explicit knowledge required for an environmental management system and related tools. | Absorptive capacity framework | Research paper/observations and semi-structured interviews | SME sector in general |

| Jansson et al. [103] | 2017 | Sweden | To examine the relationships between market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation, in relation to sustainability commitment, sustainability practices and management values in SMEs. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires | SME sector in general |

| Choi and Lee [104] | 2017 | South Korea | To propose a framework for integration and management of sustainability factors and their application for SMEs. | ---- | Research paper/Case studies | Manufacturing firms |

| Tomšič et al. [105] | 2015 | Slovenia | To analyze the link between corporate sustainability and economic performance. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires | SME sector in general |

| Johnson [106] | 2015 | Germany | To compare the rates of awareness and implementation of multiple sustainability management tools in SMEs and examine managerial and organisational characteristics that can influence the rates of adoption. | Innovation diffusion model | Research paper/questionnaires | SME sector in general |

| Williams and Schaefer [107] | 2013 | UK | To explore the motivations of managers of environmentally pro-active SMEs to engage with environmental issues, focusing particularly on the climate change agenda. | ---- | Research paper/interviews | SME sector in general |

| Moore and Manring [38] | 2009 | ---- | To analyze the SME sustainability advantages in contrast to MNEs and to study different scenarios for SMEs to optimize sustainability. | ---- | Conceptual paper | SME sector in general |

| Broccardo and Zicari [108] | 2020 | Italy | To explore the role of sustainability in the business models of SMEs. | ---- | Research paper/questionnaires | Wine sector |

| Kiefhaber et al. [109] | 2020 | New Zealand | To investigate which identities are critical for SMEs engagement in sustainability and how these identities interrelate with their institutional environment. | Identity theory and organisational institutionalism | Research paper/interviews | Hospitality businesses |

| Journal Title | IF (2019) | IF (2020) | # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Strategy and The Environment | 5.483 | 10.302 | 11 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 7.246 | 9.297 | 6 |

| Journal of Business Ethics | 4.141 | 6.43 | 2 |

| Sustainability | 2.576 | 3.251 | 2 |

| Organization & Environment | 3.333 | 6.116 | 1 |

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 3.986 | 7.968 | 1 |

| Journal of Small Business Management | 3.120 | 4.544 | 1 |

| Journal of Environmental Management | 5.647 | 6.789 | 1 |

| Journal of Business Research | 4.874 | 7.55 | 1 |

| Technology in Society | 2.414 | 4.192 | 1 |

| Production Planning & Control | 3.340 | 7.044 | 1 |

| Processes | 2.753 | 2.847 | 1 |

| Advanced Science Letters | 1.253 | 1 | |

| Australasian Journal of Environmental Management | 1.196 | 1.833 | 1 |

| British Journal of Management | 2.750 | 6.567 | 1 |

| Futures | 2.769 | 3.073 | 1 |

| Innovation—The European Journal of Social Science Research | 1.055 | 1.867 | 1 |

| International Journal of Production Economics | 5.134 | 7.885 | 1 |

| International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing | 2.090 | 3.205 | 1 |

| Economic Research—Ekonomska Istrazivanja | 2.229 | 3.034 | 1 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 4.542 | 8.741 | 1 |

| Energy Policy | 5.042 | 6.142 | 1 |

| Entrepreneurship and Regional Development | 2.928 | 5.149 | 1 |

| Engineering Construction and Architectural Management | 2.160 | 3.531 | 1 |

| Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal | 3.354 | 1 |

| Authors | Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Nº | % | |

| Dey P.K. | 4 | 9.52 |

| Malesios, C. | 4 | 9.52 |

| Abdelaziz, B.F. | 3 | 7.14 |

| Chowdhury, S. | 3 | 7.14 |

| De, D. | 3 | 7.14 |

| Roxas, B. | 2 | 4.76 |

| Font, X. | 2 | 4.76 |

| Johnson, M.P. | 2 | 4.76 |

| Kornilaki, M. | 2 | 4.76 |

| Other authors | 17 | 40.48 |

| Clusters | No of Papers | References |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability and SMEs’ Performance | 21 | Bartolacci et al. [29] Boso et al. [99] Broccardo and Zicari [108] Caputo et al. [84] Chang and Cheng [96] Chege and Wang [22] Choudhary et al. [85] Dey et al. [95] Dey, Malesios, De, Budhwar et al. [92] Dey, Malesios, De, Chowdhury et al. [94] Yus Kelana et al. [91] Knight et al. [52] Malesios et al. [97] Mani et al. [9] Panwar et al. [81] Quartey and Oguntoye [93] Roxas et al. [80] Schmidt et al. [98] Shihadeh et al. [88] Tomšič et al. [105] Viesi et al. [101] |

| Green and environmental management issues in SMEs | 19 | Bakos et al. [51] Chang and Cheng [96] Chege and Wang [22] Choudhary et al. [85] Dey et al. [95] Dey, Malesios, De, Budhwar et al. [92] Dey, Malesios, De, Chowdhury et al. [94] Hofmann et al. [86] Johnson [102] Knight et al. [52] Loucks et al. [31] Redmond et al. [90] Roxas and Coetzer [82] Roxas et al. [80] Schmidt et al. [98] Tilley and Fuller [87] Viesi et al. [101] Westman et al. [27] Williams and Schaefer [107] |

| Social and cultural issues in SMEs and their impact on sustainability policies | 3 | Kornilaki and Font [79] Kraus et al. [3] Westman et al. [27] |

| Values, skills, and capabilities needed for sustainability in SMEs | 21 | Bakos et al. [51] Caputo et al. [84] Choi and Lee [104] Hofmann et al. [86] Imran et al. [83] Jansson et al. [103] Johnson [102] Kiefhaber et al. [109] Klewitz [89] Knight et al. [52] Kornilaki and Font [79] Kornilaki et al. [30] Moore and Manring [38] Panwar et al. [81] Redmond et al. [90] Roxas and Coetzer [82] Schmidt et al. [98] Upstill-Goddard et al. [47] Westman et al. [27] Williams and Schaefer [107] Witjes et al. [100] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins, A.; Branco, M.C.; Melo, P.N.; Machado, C. Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116493

Martins A, Branco MC, Melo PN, Machado C. Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116493

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Adelaide, Manuel Castelo Branco, Pedro Novo Melo, and Carolina Machado. 2022. "Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116493

APA StyleMartins, A., Branco, M. C., Melo, P. N., & Machado, C. (2022). Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability, 14(11), 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116493