1. Introduction

In recent years, innovation, in the broad, generic sense of the word, has come to play a central role in EU rural development policies, particularly in the most disadvantaged rural areas [

1,

2,

3,

4].

In recent research on rural development, there has been increasing interest in neo-endogenous approaches. These go beyond exclusively endogenous or exogenous models, focusing instead on the dynamic interactions between rural areas and their broader political, institutional and business contexts and their surrounding natural environment [

5]. The neo-endogenous approach tries to merge the positive aspects of exogenous and endogenous theories, combining bottom-up and top-down planning, internal and external participation and networks, vertical political-administrative relationships and horizontal links between local actors and between neighboring territories [

1,

2].

This neo-endogenous model pays special attention to the cultural and social aspects of innovation [

1,

6], as manifested in the LEADER approach, which encourages innovation and a bottom-up approach to rural development thanks to the action of local public–private partnerships, called Local Action Groups (LAGs).

The LEADER initiative, which first appeared in 1991, has become one of the most emblematic rural development schemes within the EU and beyond. Built on recent theories of neo-endogenous rural development [

7], LEADER offers both a theoretical approach and a practical method for successfully encouraging rural development. The name comes from the French acronym: Liaisons Entre Actions de Developpement de l’Economie Rurale, which in English translates as: “Links between the rural economy and development actions”. LEADER works as a “seed”, from which rural development sprouts and grows. It combines aspects of both governance and government and takes practical tangible form in grants to co-finance a range of projects in rural areas.

The LEADER approach has several important specific features: networking, territorial perspective, integrated multi-sector action, local decision-making, economic diversification, bottom-up approach, innovation, LAGs and public–private partnerships. It has been implemented over almost thirty years, initially in the 1990s as an EU-wide Initiative, and, more recently, over the last fifteen years, as specific actions within national and regional Rural Development Programmes (RDPs).

International and comparative studies [

2,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] confirm that the implementation of the LEADER initiative has revealed critical issues and limitations in various European countries mainly due to inherent local factors (such as local governance, styles of government, a lack of active awareness of local resources and needs, social capital and local entrepreneurship). They also indicate that the future of LEADER will necessarily involve changes and innovations from within, rather than being externally-driven. The small local scale must also be reinforced in projects, actors and initiatives based on internal decision-making and local strategy plans.

The innovative character of LEADER was highlighted in a document issued by the Official Observatory in 1997. The LEADER approach was defined as a methodology capable of mobilizing and implementing local development, which could not be reduced to a fixed set of measures. In other words, LEADER had to be a sort of “laboratory” to create knowledge and skills at a local level, to experiment with new ways of meeting the needs of local communities. This was therefore the ultimate aim of this holistic, bottom-up, integrated, participatory approach to rural development. The methods/phases of implementation revolved around the involvement of local actors, the creation of public–private partnerships (LAGs), the identification of local resources and needs, and the drafting, implementation and evaluation of local strategies. This involved the refocusing of local resources, actors and dynamics.

For their part, Moulaert et al. 2005 [

3] defined social innovation (SI) as new forms of civic involvement, participation and democratization, contributing to the empowerment of disadvantaged groups and greater citizen involvement, resulting in an improvement in the quality of life in a particular area.

From a programmatic point of view, there are therefore clear links between SI and LEADER, which seeks to achieve its objectives through innovation, the improvement of social capital, and the creation of public–private partnerships, networks and organizations to promote territorial and community projects. Additionally, LEADER helps create social learning processes through training courses or through its own planning process; building trust between the actors involved, social capital and public–private partnerships. It also actively encourages local entrepreneurship through its grant and investment program.

According to Neumeier (2017, 35) [

14], SI “affects at least one user or context or procedure: produces a solution more effectively than the pre-existing alternatives could; constitutes a long-term solution; and is adopted by “others” who do not belong to the initial group of innovators”. Schematically, SI has three fundamental phases: problematization (the identification of a need or a solution by an actor or group of actors); expression of interest (the recognition of the collective advantage and the addition of other actors); delineation and coordination (the last step, which gives rise to a new form of coordination and organization) [

14]. In many cases, this is reflected in multi-territorial projects, such as Transnational Cooperation Projects (TNCPs), one of the most salient features of the LEADER approach. It is also visible in the strategies involving various micro-projects within a cluster, and finally, in other actions that transcend the LEADER approach, in which rural areas are also actively involved.

In fact, within the context of neo-endogenous development, the success of SI is closely related to the quality of a set of physical, environmental and sociocultural elements jointly referred to as “territorial capital” [

5]. Given that the territorial context is permeable to external stimuli, the LEADER approach could play a key role in promoting SI—through creative, new investments and projects with public and private funding— from the outside to the extent that they can remove infrastructure-related obstacles and bottlenecks. In this sense, it is important to assess the impact of external interventions on the local context, and the relationships that these interventions have created between: (i) local stakeholders; and (ii) local stakeholders and local assets; and finally, to explore the changes that they have induced in local organization (identity transformation or consolidation). In rural areas, the LEADER approach can be considered an important part of SI. It is also important to highlight its inclusive, all-encompassing territorial approach, rather than focusing on specific aspects or sectors.

As Dargan and Shucksmith [

15] emphasized, a significant change can be observed in rural development literature in terms of the knowledge and support provided for social learning processes. To this end, conceptions of innovation have shifted from a linear view of the farmer as the recipient of externally developed, codified knowledge and technological packages disseminated by extension services, towards a model in which innovation is conceived as a co-evolutionary learning process that takes place within the social networks of an array of actors. SI initiatives, therefore, try to embrace the whole context and focus on specific, especially immaterial, assets in the form of places [

5,

6], knowledge and social networks. In this way, SI has evolved, acquiring new features that remain challenging to interpret and measure, so giving rise to an essential, still open debate in this field of research [

16,

17,

18]. Social capital is vital in ensuring the effectiveness of development programs, particularly the LEADER approach, as it helps develop all the main elements that have proved decisive in the activation of rural development paths, and in particular, the capacity of the stakeholders to reflect on the material and immaterial resources required for the social and economic development of the area. It also extends the stakeholders´ capacity to cognitively create territorial capital and enables them to build consensus and therefore trust in a social body, in which different, sometimes opposing interests coexist [

19].

Finally, the added value provided by the LEADER approach is understood as the main tangible and intangible inputs, results and impacts obtained thanks to the implementation of neo-endogenous projects in rural areas, which bring about sustainable development and social change, one of the primary aims of SI projects (Vercher et al., 2022) [

20].

With this in mind, the aim of this paper is to analyze the nature of SI within these projects and the added value it produces, thanks to the networks of actors created. To this end, we will be focusing on specific recent initiatives in rural areas of Italy and Spain, in which the LEADER approach has been applied. These projects take various different aspects into consideration, including entrepreneurship, especially those conducted in areas facing severe problems of rural depopulation or with poor accessibility and difficult physical conditions. Without seeking to provide an exhaustive analysis, we explore the practices implemented in the territories in a bid to understand the nature of the innovations produced by approaching this issue from an SI perspective, and the scale of specific projects and initiatives. The implementation of these specific initiatives produces a wide variety of social innovations, which, in many cases, have been neglected by those analyzing rural development practice. This is largely due to the fact that in the past rural development schemes tended to focus on the stakeholders involved, rather than on the changes and innovations they produced.

To this end, we focus specifically on the LEADER projects defined as innovative in the European Rural Network database (ENRD). We also assess how much these projects are affected by traditional models and/or external influences, and in particular the contribution made by LEADER to innovative practices. After establishing the context of SI and its role in rural development, the paper then presents the methodology, the results of our analysis of the various projects in Spain and Italy, and finally, the discussion and conclusions.

2. Theoretical Framework—Actors, Social Innovation and Added Value in LEADER Projects

In recent years, essential changes have been made in the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to take into account the vital role of innovation in this sector (with a transversal impact across the different rural development programs). An official communication from the EU entitled “The Future of Food and Farming” [

21] recognized the role played by development policy in the agricultural economy and, in particular, in helping create the conditions to halt the decline of the rural population. This was to be achieved not only via financial investment, but also via the acquisition of skills, know-how, training and information, i.e., the improvement of social capital. With this in mind, the rural development programs for the period 2014–2020 have progressively tried to expand innovation and mitigate the potential risks inherent in farming compared to previous cycles. However, the lessons learned from previous experiences show that these tools cannot act in isolation and that their impacts on the territory take longer to verify. They are certainly not measurable in the short term and provide much more than purely economic benefits. In addition, the fact that farmers still have limited access to the latest technical and scientific advances is particularly evident in many remote rural areas, due to the virtual (poor broadband) and geographical distance from most scientific and academic centers. Structural obstacles, such as excessive bureaucratization, must also be reduced to a minimum. In this study, when interpreting the types of SI achieved in these LEADER projects, we followed the Oslo Manual [

22], the international reference guide for collecting and using data on innovation.

Within this context, entrepreneurship is promoted by neo-endogenous rural development practice, and is one of its main positive effects. Local businesspeople use territorial assets, traditional skills and knowledge combined with external technical and scientific knowledge and technologies to develop new economic initiatives. This process involves more than just entrepreneurs. Town councils, associations and LAGs also play an important role establishing public–private partnerships to manage the LEADER initiative, putting the neo-endogenous rural development in practice. Other achievements of LEADER include economic diversification, added value in the production chains, and fomenting other business activities complementary to the farming sector. Another important step forward is the change it engenders in the mentality of the inhabitants of rural areas, from a negative, passive acceptance of their situation to a more positive, pro-active mindset working towards the goal of rural development.

LEADER has also encouraged business creation by women and young people, two groups vital for the survival and future prosperity of rural areas. Projects like these bring different stakeholders into contact with each other, constructing new networks to fight the marginalization of country areas. Although many have quite low budgets, they are highly creative and flexible, and successful at matching funding with needs. The empowerment and re-appropriation of living spaces from a material and identity point of view have become key aspects of these initiatives. Some of the topics covered by the LEADER projects included: the provision of previously non-existent basic services such as delivery services; mobility and logistics solutions; high-speed internet and online services; support for young people and generational renewal; social inclusion and the settlement of migrants. These generated multiplier effects in favor of the entire community, so enhancing social inclusion, general wellbeing and the quality of life. Furthermore, by pioneering new sectors such as tourism in rural areas and promoting high-quality food products and local crafts, it has fostered economic diversification [

23].

However, the practical application of LEADER on the ground has revealed various negative aspects, such as the “imbalanced territorial development” produced by concentrating the projects in the most dynamic, most populated rural areas, which already have a well-established business network, and neglecting the more depressed areas with very little social capital and few businesses [

24]. Specific measures in support of the most remote, most sparsely populated areas need to be introduced. Another drawback is that local decision-making is often controlled and dominated by local elites, so sidelining those people who do not have the necessary contacts and economic resources to present projects that will be successfully approved for LEADER funding [

25]. Despite specific action to promote their involvement, women and young people remain less likely to implement LEADER projects than established male entrepreneurs or public entities such as local councils, so giving rise to what is sometimes referred to as a “project class” [

9].

Despite these drawbacks and bearing in mind that LEADER by itself is insufficient to bring about a complete breakthrough, it does provide an excellent laboratory, in which to observe, learn and test out good practices, and has made a very important contribution, by encouraging rural tourism, promoting natural and cultural heritage and other local assets, providing important services—public and private—and fomenting high-quality local food production, etc.

Within these neo-endogenous local development practices, many of which had a highly innovative component, Esparcia [

26] noted the different roles played by the key actors, and the networks they generated. These projects produce hybrid combinations of external scientific knowledge with traditional local know-how, constructing interwoven fabrics, in which the presence and financial support of public actors is often essential in the initial phases. Equally vital is the participation and commitment of the LAGs, which foster entrepreneurship and innovation. However, Navarro et al. [

4] revealed that institutions such as universities and research centers, which could potentially play a crucial role in bringing innovative projects to fruition, are largely absent. The same applies to business associations. These authors also highlighted the inefficiencies and excessive bureaucracy produced by regional government intervention, as compared to when the management and local implementation of the LEADER strategy is left in the hands of the LAGs.

When it comes to creating SI projects, Nordberg and Virkkla (2020) [

27] emphasized the importance of a quadruple helix (firms; citizens and civil society; public sector; and universities and educational institutions). They also stressed that the networks they created were a source of new opportunities for local communities; and the need for collaboration between rural communities and other groups and organizations outside their communities. For Dax et al. (2013) [

28], the potential benefits of the LEADER approach for SI have been limited by rigid coordination structures and hierarchical mindsets. For their part, Dargan and Schucksmith (2008) [

15] insisted on the importance of SI, as a means of bringing together new forms of knowledge in collective learning processes for rural development.

In the case of the added value provided by the LEADER approach, Thuessen and Nielsen (2014) [

29] showed that at the LAG level, democratization and bottom-up decision making are the main positive impacts of LEADER implementation, while other potential plus points are not used to full advantage.

3. Materials and Methods

The projects analyzed came from the official database of the European Network of Rural Development [

9], which offers an interesting overview of each initiative (promoter, summary, objectives, results, activities, lessons and recommendations, among others), many of which could be considered as good practices.

This research used a selection of projects from rural areas in Italy and Spain, through the choice of specific keywords. The words used in the initial search were: “depopulation” and “marginal rural areas”. We then added “innovation”, “entrepreneurship” and “LEADER”. In this first phase of selection, 24 projects were identified, 13 from Spain, and 11 from Italy.

Within this selection, we analyzed either one or two projects for each type of promoter: TNCPs promoted by several LAGs; projects supported by public entities (mainly local councils); and finally, those led by small companies and entrepreneurs (

Table 1). These projects are representative of each of the profiles of project promoters. Our analysis was based on the information contained in the description of these eight projects.

According to the methodology applied by Esparcia (2014) [

26], we then went on to consider the key actors involved and their functions (promoters, beneficiaries, funding, entrepreneurs, facilitators, informants, those providing support for promotion and organization, researchers, among other stakeholders), the main changes that took place and other aspects of the projects.

The next stage was to use compatible indicators to study the types and interpretations of SI proposed in the literature, and in particular in the Oslo Manual [

4,

25]: cooperation between actors, creation of new networks and partnerships, organizational/identity changes, social groups working for the same goals, institutional and collective learning aimed at improving knowledge of common problems, increasing people’s capacity to engage in cultural interaction and exchange, and new ways of organizing and involving people in the decision-making process (

Table 2).

We also conducted in-depth interviews with the promoters. One interview for each type of promoter: one with a small entrepreneur -Agroberry-, one with a LAG -Wolf-, and one with a public body -Living Villages-); examining the types of stakeholders in the implementation phase and the roles they play, the contributions made by these projects in terms of SI and the added value they provide.

In the results section, we will now go on to look, firstly, at the actors involved, and secondly, at the SI and the value added. A network of actors has to be established before SI can be achieved. The SI achieved by a project is sometimes inseparable from its added value. A contribution to SI could also be regarded as an added value and vice-versa.

4. Results—Analysis of the Projects: A Comparison

4.1. The Role of Actors

Right from the start-up and implementation of these projects, the different actors begin to make increasing numbers of contacts and connections, with people with different roles operating inside and outside their rural areas. In this way they contribute, directly and indirectly, to the successful implementation of these initiatives. These networks can be complex or simple, weak or strong, large or small, but the support they provide is always one of the main features of neo-endogenous rural development practices. The LAG itself forms an important network to introduce and implement the LEADER approach, and draw up the local strategy (Community-Led Local Development (CLLD)). It also carries out essential functions of intermediation, training and tutoring, and provides a channel through which all the contacts can communicate. Other important actors include for example the local administration, normally town councils, which, as well as promoting projects themselves, can provide a physical infrastructure, in which others can carry out their projects, or offer support information or advice.

In the case of the Living Villages initiative, the project focused [OR a project focusing] on attracting immigrants, a total of 28 municipalities played an important role raising awareness in their local communities about the problem of depopulation. Municipalities prepared an inventory of useful resources and services for potential new settlers and a list of the needs of each municipality and an action plan to improve their capacity to welcome new settlers and encourage current residents to stay. In this way they formed a network involving several LAGs from the Aragon region (Spain), local volunteers, entrepreneurs, and civic and social associations. The involvement of local volunteers (100 people) was key to the success of the initiative, offering information about employment, housing, internet connection, communication networks and services to the population. The network established between the LAGs facilitated communication and made it easier to transfer the results of the projects [

23].

This collaboration between internal and external actors, between marginal groups and local volunteers, can also be seen in the Terre and Comuni project (Alvito, Italy). This initiative sought to bring local people and immigrants together to solve some of the social problems experienced by the new arrivals and by unemployed locals. This project was part of a larger initiative promoted with EU funds. It was set up in response to a very specific set of problems in that particular area, a small community in the Comino Valley that was very close to two centers for asylum seekers from Africa and the Middle East. The local community was suffering many of the typical problems of inland rural areas (e.g., a declining aging population) and the migrant community was largely demotivated and at evident risk of marginalization. The first phase of the project involved the local LAG, setting up a social enterprise, which would incorporate an increasing number of actors from both the local and immigrant communities. The project sought to promote integration between locals and immigrants. For the first time in this area, the immigrants had the chance to positively engage with the local community. This new form of cooperation produced important results, such as the cultural association (Rise Hub) formed once the project came to an end thanks to the experience acquired by the actors from previous training courses within the LAG, involving both local unemployed and immigrants. Working closely with the LAG, this association has successfully initiated various small and medium scale projects “building on its members’ knowledge, linking to other ongoing projects concerning migrants, and/or testing original paths” [

30].

The continuity of both these projects in other similar initiatives or micro-projects, and the essential role played by the main actors (local people and migrants) meant that positive results were achieved, in particular in terms of social inclusion. Another interesting step forward was the creation of networks between new settlers and local inhabitants in the form of associations or even public–private partnerships.

Public sector involvement focused mainly on the creation of businesses and employment. Another important factor in the success of rural development projects is the involvement of educational institutions, such as vocational training centers or universities, as in the case of Terre & Comuni, Cowocat and Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk [

31]. These institutions can contribute directly through applied research or by providing scientific support for the projects. In general, universities could play a more active part in these processes.

Other groups, such as local business associations, can also participate by supporting entrepreneurs or by promoting projects themselves. Finally, of course, the promoters´ families can provide valuable input in the form of traditional local knowledge and experience, in addition to continuous financial support. This shows how some projects establish complex networks encompassing a wide range of groups and individuals from inside and outside the local community, while others involve much simpler networks with just a few actors, such as the entrepreneur and their family.

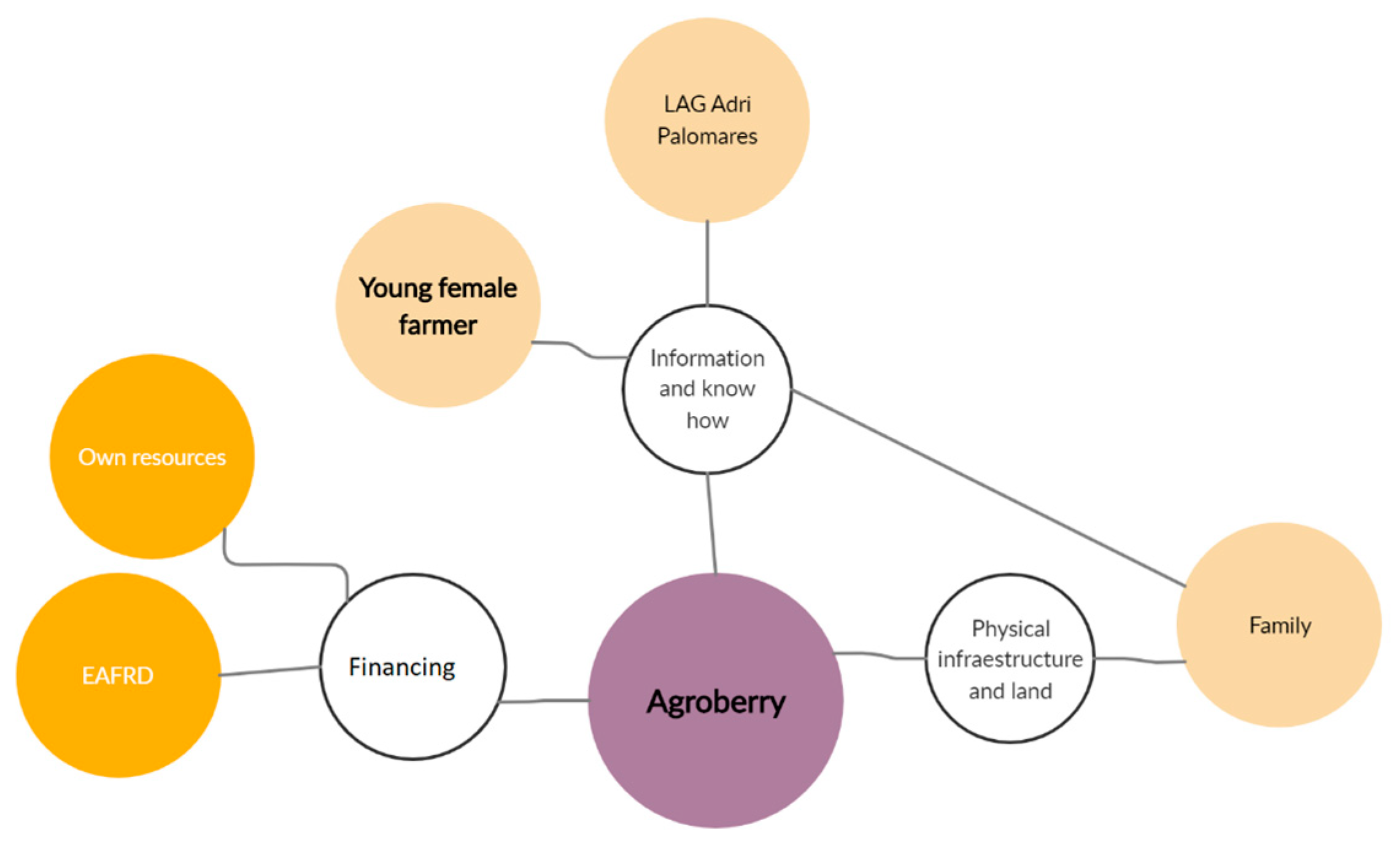

A case in point was the Agroberry Original from Zamora project, in which a young woman farmer set up a blackberry plantation in a wheat and barley production area. In this way she created added value by developing a new range of products, selling directly to fruit consumers and stores. Her family played a vital supporting role by providing the physical infrastructure and the land required for the project. The simple network established also involved the LAG, advising about the innovative products that she could develop (

Figure 1) [

32].

A very similar project called Diversifying a Young Female Farmer’s Income by Investing in Farm Tourism was carried out in the Marche region of Italy. This was a small private initiative launched by an individual entrepreneur on the basis of her specific knowledge and experience. The aim was to make the most of her existing resources. In this case the LAG provided mainly financial support. This kind/type of project has a very limited knock-on effect in terms of interactions with other actors and as a benefit to society as a whole. On the other hand, traditional skills and experience, academic and scientific knowledge, and the pre-existing infrastructure all represented fundamental pillars in the starting of both ventures [

33].

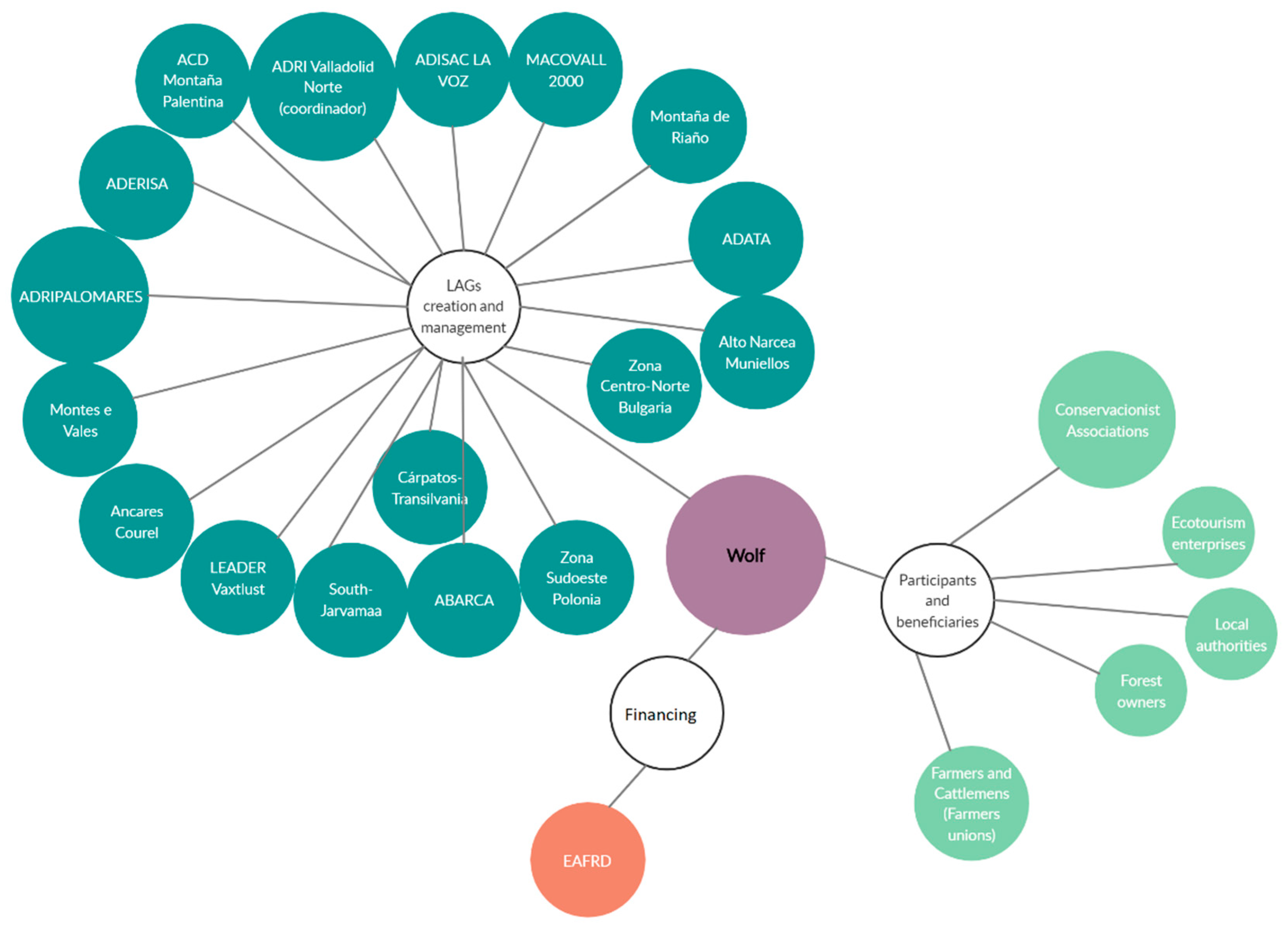

Another much more complex project with completely different aims is the Wolf TNCP. The aim of this project was to try to reconcile the often conflicting interests of the members of local communities. The objective was to avoid disputes, while respecting wildlife, especially wolves and their habitat, so as to ensure that they were as compatible as possible with human practices, in particular livestock farming, in those parts of the EU still inhabited by wolves. This conflict has been reduced or even removed thanks largely to this initiative. Now, according to the leading LAG manager involved, a peaceful conversation can be had about this animal, an open debate, without fighting, with farmers and conservationists expressing their different points of view. It is no longer the previous “ecological monologue”. Even though wolves continue to attack livestock, it happens less frequently, and “revenge attacks by shepherds” have also declined. Social networks and relationships have been created and improved. The direct involvement of farmers (farmers unions), forest owners, local authorities, ecotourism enterprises and conservationists (associations) was essential for the success of the project (

Figure 2).

The Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk project was promoted by a local cooperative in Tuscany in collaboration with the Veterinary Department of the University of Pisa. The members of the cooperative decided to expand their business. The first phase of their project was to reorganize an old farm inside a natural reserve. After that, they got the local councils in the area involved and started a donkey breeding business. The subsequent phases of the initiative involved various other actors, and in particular the University of Pisa. The University had already collaborated on other projects relating to the environment and the preservation of biodiversity. The Donkey Milk project had three main stages. The initial goal was to produce high-quality milk products and this was progressively expanded by bringing in different actors to produce a broader range of products (cheese, yogurt and possibly cosmetics).

In both projects, the objectives seem to focus on solving a problem, promoting local assets (wolf habitat or donkey herds), improving the quality of the products, and creating quality brands with added value. The main actors were the farmers [

34].

Figure 2.

The complex network of Wolf TNCP. Source: [

35]. Created by the authors.

Figure 2.

The complex network of Wolf TNCP. Source: [

35]. Created by the authors.

The involvement of local councils, creating joint public–private projects and partnerships, is another shared feature of these examples (as in Wolf, Living Villages, Terre & Comuni [

36] and Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk).

These projects have important shared features that do not arise in those promoted by an individual businessperson. These include the complexity of the networks and the partnerships between public and private sector actors. The mix of external (universities, immigrants, new settlers, young promoters) and internal actors (volunteers, municipalities, older people, unemployed, entrepreneurs); the inclusion of marginal or sometimes excluded groups (young people, women, unemployed, farmers, the elderly, and immigrants); the active involvement of local inhabitants and farmers; the creation of new networks thanks to these initial projects (associations, collaboration between entrepreneurs or between different stakeholders—i.e., farmers and ecologists—with universities, extending to other rural areas); the crucial role of facilitators—LAGs—and local leaders —mayors, entrepreneurs, visionaries—are crucial aspects common to all these initiatives; and finally, the continuity of these projects with other parallel or improved initiatives seeking similar or complementary goals.

4.2. The Nature of Innovation and the Added Value It Provides

The creation of networks and territorial and inter-territorial partnerships through neo-endogenous rural development initiatives increases the value of territorial capital [

5]. The LAGs, individually, or in coordination with other actors, such as local administrations, entrepreneurs and associations, can improve and enhance endogenous assets, for example by providing them with a competitive advantage. They can also help achieve development objectives and reinforce territorial identity. In addition, the combination of a large number and variety of actors, networks and objectives can give rise to a large, complex number of innovations, another specific feature of the LEADER approach.

The most significant, most paradigmatic types of innovations are those linked to the creation and promotion of social capital, one of the main reasons for the implementation of projects of this kind. In fact, the main objectives of these initiatives include knowledge transfer, social inclusion, resolution of conflicts, the maintenance of the young and especially female population, the creation of networks between internal–external actors, and the support for underprivileged groups in society. Other types of innovations, although also essential, tend to play a secondary role.

In order to identify the innovative content of these projects, compatible with the neo-endogenous approach, we established various indicators of social innovation (see

Table 2 above). The projects that achieve the highest number of indicators of social innovation are typically characterized by the involvement of a range of different actors who are progressively engaged with and included in the project. The local community plays an active part throughout the process. The key element marking a clear distinction between the different projects in terms of the indicators of social innovation does not seem to be the type of network (simple or complex), but the degree of involvement of the local community in the project. The participation and support of the local community strengthens the project and allows it to build a framework, within which it can develop and evolve. The full involvement of local inhabitants is required to ensure the success and consolidation of these experiences. It is also a source of local empowerment, of reconnection between local people and places. This helps develop territorial identity, constructing links between the people and the place they live in, commitments and ties with rural areas; in short, projects that allow people to continue living in rural areas. One of the most essential benefits of local participation is to change the mentality of local residents (“natives” and new arrivals) and empower them with hope and confidence for the future. These inputs are extremely difficult to obtain with other types of policies and projects. The involvement and participation of local actors, and the improvement in social capital, produce a new form of coordination and organization that is rarely found in other types of initiatives. For example, the LEADER projects are substantially different from those carried out recently by Innovation and Operational Groups/Projects, in the agricultural, forestry and food sectors, which are made up of different types of stakeholders (farmers, agri-food industries, public and private research centers, technological centers, among others) seeking to achieve a technical and/or sustainable innovation, solve a problem or take advantage of an opportunity. In these, the sectorial approach, the high technological, scientific and research components, and finally, the priority given to economic aspects tend to reduce other social, territorial, and global impacts.

When local people are treated as the prime beneficiaries and between them have a useful, varied set of skills and experiences, complex networks can emerge involving new forms of collaboration between the various actors, new forms of exchange of knowledge and skills, and new ways of involving organizations and people in decision-making processes (Rural Coworking Spaces, La Exclusiva, Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk). In the simpler networks, such as those run by individual private entrepreneurs, where local people only benefit from the project indirectly, the following elements were highlighted: innovations based on personal experience and local traditional knowhow, a change of mentality affecting above all the promoter, and innovation aimed essentially at obtaining a new product or service (Agroberry Original from Zamora, Diversifying a Young Female Farmer’s Income by Investing in Farm Tourism).

The essential qualitative, intangible components of LEADER projects include: collective learning aimed at improving knowledge of common problems, an increase in people’s capacity to engage in cultural interaction and exchange, cooperation between actors, new tools and methods for identifying and making best use of local resources, new ways of organizing and involving people in the decision-making process, new forms of partnership and cooperation, and social groups working towards the same goals. Many of these projects have a common defining element, namely the active involvement of local residents and people at risk of marginalization and exclusion. They also help create new forms of dialogue and consensus, the trust required to solve local conflicts, greater knowledge of common problems and a shared path towards the solutions (Wolf TNCP, Living Villages, Terre & Comuni). Most of these values are very difficult to foster using other kinds of policies and are difficult to measure and evaluate.

In the case of Wolf TNCP, new forms of dialogue and consensus were introduced in a bid to help resolve local conflicts. This was achieved via the following participative tools: seminars, meetings, debates and events, in which all the actors involved took part, and through a range of environmental training courses.

The role of the LAGS is central to both the Spanish and Italian experiences. LAGs provide essential support but need to be strengthened. It is also important to remove infrastructure-related obstacles and bottlenecks. Another element that must be considered is the often marginal role assigned to local residents. They are often treated as mere passive beneficiaries of the interventions and, are rarely viewed as an active, cooperating community capable of offering significant contributions. In the latter case, local participation often helps guarantee the effectiveness and durability of the project, by engaging in the initial phases, providing financial help, voluntary work, and knowledge.

In short, the degree of complexity of the SI and the added value provided by a project depend on the types of entrepreneurs and the networks they establish with other stakeholders. In the cases of LAGs, these come in the form of public–private partnerships, sometimes with other LAGs (TNCPs) (Cowocat, Wolf, Terre & Comuni) and sometimes with other actors (Living Villages). These projects ticked practically all the boxes in terms of the SI indicators. For Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk, the collaboration between internal (Cooperative) and external (University) actors produced highly significant SI results. By contrast, the projects carried out by individual entrepreneurs (Agroberry, Diversifying a Young Female Farmer´s Income by Investigating in Farm Tourism) obtained far fewer SI indicators. These projects can be useful however, in terms of enhancing territorial identity and agrarian heritage, and can increase the capacity of disadvantaged people to engage in knowledge exchange and local development (

Table 3).

5. Discussion

The main theoretical and practical findings and implications of this study could be summed up in the next paragraphs. The generation of neo-endogenous rural development practices needs a combination of external knowledge and local assets, making a crucial contribution to SI. Additionally, the exogenous and endogenous mechanisms and rules influence the quality and the number of contributions these projects make to SI. Finally, bureaucratic procedures and top-down approaches can reduce the number and effect of SI projects.

The successes and impacts of these social innovation processes are highly dependent on the degree of complexity of the networks established by the stakeholders. Therefore, it is relevant to note the necessity of a high number of stakeholders in the implementation phase of these projects, being decisive for their success, the high involvement of local communities. Furthermore, it is crucial to note the different roles played by different actors: charismatic local leaders and visionaries, who can raise awareness in the community; LAGs, not only as public–private partnerships, but also as technical and innovative technical staff: tackling problems affecting disadvantaged collectives, creating spaces for learning, or intermediating in different problematics and processes; and the third sector, producing a broader set of benefits, beyond the purely economic. Moreover, the minor and limited outcomes, in terms of SI, of the projects promoted by small private entrepreneurs.

Innovation springs from a concrete need that is suffered and must be solved by the community, and their more or fewer aspirations will explain how radical these SIs will be. These projects’ contributions, impacts, and effects are more important than the actors involved, and those are complicated to size and evaluate: i.e., dignity, distinction, and solidarity. SI reinforces the social dimension of the practice of rural development, communities, and rural society’s well-being.

The more relevant aspect of these initiatives is that these projects can lead to social change and sustainable development. Thus, the most significant and paradigmatic types of innovations are those linked to creating and promoting social capital.

Furthermore, the necessity of this approach, SI projects, variety of social innovations, added value, internal and external stakeholders, and commitments of local communities to face the challenges and problems of deep rural areas. However, the LEADER approach must be reinforced, and this methodology is not enough to solve the problems of these territories.

Several key points emerge from our comparative study, in which the projects were analyzed from the perspective of the contributions they make to social innovation.

Firstly, by definition SI implies new forms of civic involvement, an improvement in the quality of life, an empowerment of disadvantaged groups [

3], and sometimes even social change [

20]. All the projects analyzed here share at least some of these components: Terre & Comuni, Living Villages, Wolf, Cowocat, Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk, Agroberry, and Diversifying a Young Female Farmer’s Income by Investing in Farm Tourism. However, the impact of the social innovation process is highly dependent on the degree of complexity of the networks established by the stakeholders, as are the added value and the social change that the projects provide.

Secondly, innovation springs from a specific need or emergency that is shared and must be solved by the people involved (Terre & Comuni, Living Villages), and their aspirations in relation to community needs inevitably affect how radical and far-reaching these SI processes can become [

20].

Thirdly, the crucial role of facilitators, local leaders and visionaries, who have in-depth inside knowledge of the local situation and are capable of raising awareness in the community, in many cases reducing local conflicts (Wolf). Another important factor is the ability of the facilitators, the members of the LAGs, to proactively create synergistic networks (Cowocat, Wolf). Decision-makers emphasize the need for continuous co-creation of knowledge, exchange and critical discourse on what rural development is and how to achieve it [

35]; and the need to apply a bottom-up framework to motivate residents and encourage participation [

36]. In order to understand the nature and effects of innovation, the situation of the local area before and after implementation of the project should be accurately recorded, noting all changes. In this task and in others, the LAGs must play a decisive role.

Fourthly, SI reinforces the social dimension of communities [

37] and the wellbeing of rural society. This is manifested in a community (local residents and sometimes other people at risk of marginalization) that is actively involved in the rural development projects (Cowocat, Terre & Comuni) offering their full support. In the cases of La Exclusiva or Terre & Comuni, the third sector played the lead role via the creation of cooperatives or associations, as tools to promote cooperation and support for disadvantaged groups, an example of the quadruple helix proposed by Nordberg et al. [

27] for promoting SI. The decisive factor for the success of these projects was therefore the involvement of local communities [

27]. The LEADER approach has been influential in reducing rural disparities [

38,

39,

40]. Additionally, for example in the case of Agroberry, the LEADER approach has been decisive in enabling women to become entrepreneurs [

41]. It has also highlighted the need to include young people in rural development strategies [

18].

Fifthly, the new forms of cooperation are tried and tested between different actors, increasing and improving their collective knowledge. In many cases, these involve actors from different backgrounds and their shared expert knowledge of the local situation can represent an important resource when properly harnessed and channeled (Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk). According to Dax [

12], the emphasis on combining the experience provided by external knowledge systems with the uniqueness of local resources and assets could make a decisive contribution to the long-desired incentives and social change. Obviously, this requires the involvement of universities and educational institutions, as noted by Nordberg and Virkkla (2020) [

27] (Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk).

Additionally, as Neumeier (2017) [

14] argued, a higher number of stakeholders are required in the implementation phase of a project, when a group of actors come together to form a network of common interests, exchanging ideas, know-how, skills, and the new lessons learnt (as manifested in Living Villages and Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk). The degree of complexity of this network will inevitably affect the extent of the contributions from a SI perspective.

Furthermore, the process and progress of SI in rural areas requires more extended adoption periods [

42], and the continuity of their proposals, objectives, and perspectives through similar or new initiatives. Social conflicts can only be healed with time (Wolf TNCP). This is probably one of the main obstacles preventing these projects from making a broader contribution to rural society.

Therefore, the comparison between the different projects and their promoters clearly displays the strong social role played by the LAGs: tackling problems affecting disadvantaged collectives (Terre & Comuni); creating spaces for learning about and resolving a shared problem (Wolf) or teaching the LEADER approach; exchange between different actors and territories (Living Villages); discussion and intermediation between actors in conflict (Wolf) [

35]; training, tutoring and advice for local entrepreneurs about local assets or potentialities (Agroberry); building networks and connections between rural areas with similar problems (Wolf); and favoring the communication and transferability of results, something crucial for the continuous engagement of local actors in SI projects. The projects promoted by private entrepreneurs tend to have a more limited sphere of action and therefore more simple outcomes in terms of SI.

Perhaps in the future the SI contribution made by these projects should also be enhanced. This is a task for the LAGs, which can intermediate between demands from above and below. Without the support of LAGs, private projects would be much less ambitious, with much more limited economic, social and territorial impacts. In terms of SI, the benefits are often qualitative and intangible, and the values required in terms of community involvement are very difficult to instill using other kinds of policies and cannot easily be measured or assessed. This explains why the third sector also makes a vital contribution to rural development in the form of social enterprises (La Exclusiva), which look for a wider set of benefits, beyond the purely economic.

These initiatives can encourage and enable people to establish themselves in country areas (Agroberry). We must also remember, as noted by Dargan and Schucksmith (2008) [

15], the vital role played by the members of the “project class” (LAG technical staff) (

Wolf project) and charismatic local leaders (La Exclusiva), who help build trust in these innovative networks. In some cases, the initiative itself is designed to create collective learning experiences [

2], as in Wolf TNCP.

The LEADER methodology works as a model for mixed exogenous–endogenous development, in which the rules established at national and regional levels are combined with Local Development Strategies and unwritten rules, at a local level, and where these specific projects, at first glance not always the most suitable [

40], fit and follow these external and internal rules. These exogenous–endogenous mechanisms influence the quality and the number of the contributions made by these projects to SI, via a combination of local and expert knowledge [

29] (i.e., Innovative Business Opportunities From Donkey Milk). It is also clear that the particular rural context creates both challenges and solutions, and influences the type of mechanism that is best suited to bring about a desirable SI outcome [

42] (Wolf, Living Villages, Terre & Comuni). Finally, for SI initiatives to be successful, the joint involvement and responsibility of all stakeholders is crucial [

32].

To sum up, the contributions, impacts and effects of these projects are more important than the actors involved. Sometimes, the project itself is designed to create collective learning processes [

2], as in

Wolf TNCP or Innovative Business Opportunities from Donkey Milk. Other intangible global impacts revolve around promoting dignity (new actors, skills, ideas) (La Exclusiva or Agroberry), distinction (unique identities and contributions) (Wolf or Donkey Milk), dialogue (cooperative action) (Wolf), democracy (enabled by the LAGs) (Living Villages), and of course, trust (Living Villages and Terre & Communi) [

43]. As stated by Vercher et al. (2022) [

20], these initiatives can lead to sustainable development and social change in certain rural areas.

6. Conclusions

Our analysis of the projects revealed essential aspects of the role played by the stakeholders, the different forms taken by SI, and the added value provided by these projects in rural areas of Italy and Spain affected by depopulation or with poor accessibility and difficult physical conditions.

Given that SI involves a search for social change [

20], new forms of civic involvement, an improvement in the quality of life, and/or empowerment of disadvantaged groups [

3], the initiatives analyzed here can be classified as SI projects. However, those initiated by private entrepreneurs do not seem to produce broader, more widespread effects in favor of rural society as a whole. Nonetheless, they can have some clear benefits, such as the inclusion of disadvantaged groups or the improvement of territorial identity.

In this sense, the complexity of the networks, often forming a quadruple helix of public–private partnerships, and the role of the actors (internal and external) responsible for bringing about the change is fundamental in the success of rural development projects, and can help smooth the way for more complex innovation processes. The LAGs, working individually or in coordination with other entities such as local administrations, entrepreneurs and associations, play an essential role in harnessing and improving endogenous assets. This produces numerous competitive advantages in their search for specific social and economic goals. Successful projects in turn create a fertile ground in which new networks and initiatives can develop and thrive.

The wide mix of stakeholders taking part in some projects, including local people, can give rise to complex innovations, another specific feature of the LEADER approach, in its role as an experimental social laboratory. The essence of LEADER is to support innovations of many different kinds, and in particular social innovations, that make the best possible use of local social capital.

The most successful LAGs are those that coordinate the efforts of different actors towards a common goal; support the establishment of new contacts and networks and the institutional and collective learning required for a more detailed knowledge of common problems; those that increase people’s capacity to engage in cultural interaction and exchange; find ways to reduce social conflicts and a common path to solve the problems experienced by disadvantaged groups in society. They also promote new ways of organizing and involving people in the decision-making process and new forms of partnership, and elicit new forms of collaboration in potentially dynamic environments. Even though the practical application of neo-endogenous rural development does not necessarily involve specific actions to combat rural depopulation, it has made many important contributions in the form of good practices and/or projects, which via local empowerment can help resolve these and other serious problems facing these territories.

A key aspect that emerged in this study is the need to involve the local community in the projects and processes. In top-down rural development strategies, there is little input from local communities, who tend to be overlooked or marginalized. In the LEADER approach, however, the active role of the local community is paramount. It is fundamental for the success of the project and for its long-term continuity, thanks to local people’s greater awareness of local resources, needs, and potentialities. As can be seen in the projects we analyzed, the local communities play a fundamental role in terms of the traditional know-how, skills and experience they provide. In many cases, they also provide financial backing, acting as project promoters themselves, so driving real processes of change.

In these experiences, the LEADER approach has added value by bringing about substantial cultural and social change. This in turn can give rise to significant changes in the perspective and perceptions of the local community, empowering them to find their own path towards development through a greater awareness of local resources. Our analysis of specific projects has highlighted the importance of identifying and assessing the real situation of the rural area, by encouraging greater local awareness of needs and resources useful to the whole community, bringing out different visions through the effective inclusion of the broadest possible range of actors, present and future, in rural territories. Positive dynamics in rural areas can best be achieved by the inclusion, involvement and participation of the entire local community. Decision-making should not be left exclusively in the hands of local leaders.