Organizational Well-Being of Italian Doctoral Students: Is Academia Sustainable When It Comes to Gender Equality?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypothesis

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

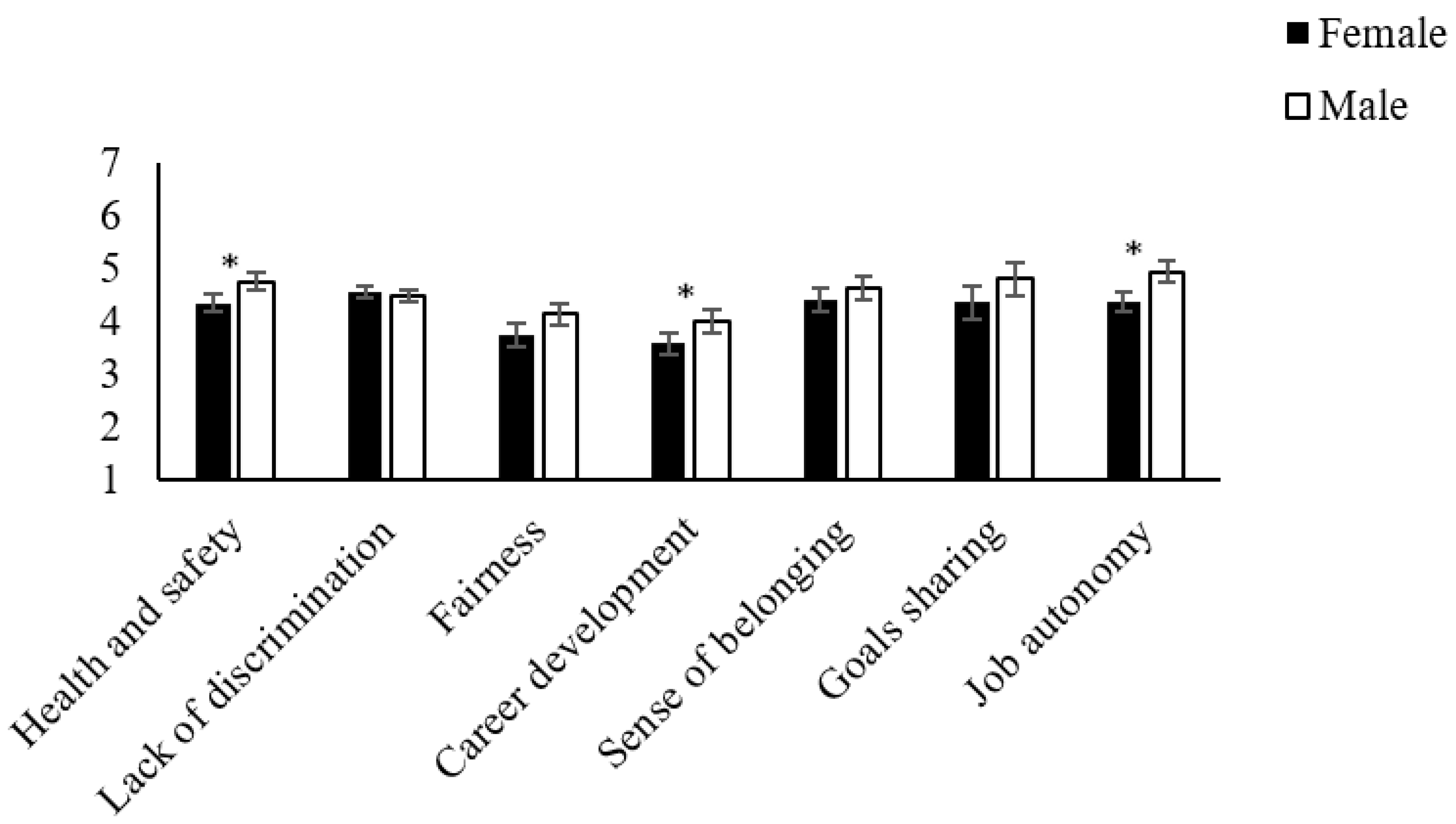

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green human resource management and green supply chain management: Linking two emerging agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pham, N.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Phan, Q.P.T. Green human resource management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manpower 2019, 41, 845–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulet, R.; Holland, P.; Morgan, D. A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Dharwal, M. Green entrepreneurship and sustainable development: A conceptual framework. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 3603–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 17, pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- York, R.; Rosa, E.A.; Dietz, T. Ecological modernization theory: Theoretical and empirical challenges. In The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau, E.; Saikku, L.; Antikainen, R.; Droste, N.; Hansjürgens, B.; Pitkänen, K.; Leskinen, P.; Kuikman, P.; Thomsen, M. Green economy and related concepts: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, F.X. Italy suspends brain-drain program. Chronicle 2006, 52, A49. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Internationalisation of Higher Education. In Policy Brief; OECD: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Constant, A.F.; D’Agosto, E. Where Do the Brainy Italians Go? In The Labour Market Impact of the EU Enlargement; Caroleo, F., Pastore, F., Eds.; (AIEL Series in Labour Economics); Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levecque, K.; Anseel, F.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Van der Heyden, J.; Gisle, L. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Posselt, J. Normalizing Struggle: Dimensions of Faculty Support for Doctoral Students and Implications for Persistence and Well-Being. J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 988–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Hansson, E. Doctoral students’ well-being: A literature review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1508171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stubb, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Lonka, K. Balancing between inspiration and exhaustion: PhD students’ experienced socio-psychological well-being. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2011, 33, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, S.; Lafarge, C. Mental Health & Wellbeing in Doctoral Students from BAME Backgrounds. Available online: https://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/id/eprint/46225/7/Bites-issue-6-Researching-educationmental-health-where-now-what-next_Feb-2021.pdf#page=18 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Wisker, G.; Robinson, G.; Bengtsen, S.S. Penumbra: Doctoral support as drama: From the ‘lightside’ to the ‘darkside’. From front of house to trapdoors and recesses. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2017, 54, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satinsky, E.N.; Kimura, T.; Kiang, M.V.; Abebe, R.; Cunningham, S.; Lee, H.; Tsai, A.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14370. [Google Scholar]

- Velardo, S.; Elliott, S. The emotional wellbeing of doctoral students conducting qualitative research with vulnerable populations. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 1522–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolston, C. PhDs: The tortuous truth. Nature 2019, 575, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avallone, F. Psicologia del Lavoro e delle Organizzazioni: Costruire e Gestire Relazioni nei Contesti Professionali e Sociali; Carocci Editore: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grawitch, M.J.; Gottschalk, M.; Munz, D.C. The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2006, 58, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, K.; Faragher, B.; Cooper, C.L. Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamers, S.L.; Streit, J.M.; Chosewood, C. Promising Occupational Safety, Health, and Well-Being Approaches to Explore the Future of Work in the USA: An Editorial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.; Hunter, B. Relationships between working conditions and emotional wellbeing in midwives. Women Birth 2019, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fila, M.J.; Purl, J.; Jang, S.R. Demands, Resources, Well-Being and Strain: Meta-Analyzing Moderator Effects of Workforce Racial Composition. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Kumar, S. Organizational Justice and Employee Well-being in India: Through a Psychological Lens. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, M.; Neira, I.; Lacalle-Calderon, M. Employee’s subjective-well-being and job discretion: Designing gendered happy jobs. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitala, R.; Tanskanen, J.; Säntti, R. The connection between organizational climate and well-being at work. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanabazar, A.; Jigjiddorj, S. Relationships between mental workload, job burnout, and organizational commitment. SHS Web Conf. 2022, 132, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck-Fries, V.; Talalaieva, O.; Krcmar, H. Highly Engaged, Less Likely to Quit?—A Theoretical Perspective on Work Engagement and Turnover in Agile Information Systems Development Projects. 2022. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2022/digital_labor/digital_labor/6/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, V.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.Y. Employees’ feedback-seeking strategies and perceptions of abusive supervision. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2022, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escardíbul, J.O.; Afcha, S. Determinants of the job satisfaction of PhD holders: An analysis by gender, employment sector, and type of satisfaction in Spain. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heilman, M.E.; Caleo, S. Gender discrimination in the workplace. In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A., King, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, L.F.; Cortina, L.M. Sexual harassment in work organizations: A view from the 21st century. In APA Handbook of the Psychology of Women: Perspectives on Women’s Private and Public Lives; Travis, C.B., White, J.W., Rutherford, A., Williams, W.S., Cook, S.L., Wyche, K.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Nyunt, G.; O’Meara, K.; Bach, L.; LaFave, A. Tenure Undone: Faculty Experiences of Organizational Justice When Tenure Seems or Becomes Unattainable. Equity Excell. Educ. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Banaji, M.R. The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L. Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, L.M.; Kaiser, C.R.; Major, B.; Kirby, T.A. It’s fair for us: Diversity structures cause women to legitimize discrimination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 57, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moulds, E.F. Chivalry and paternalism: Disparities of treatment in the criminal justice system. In Women, Ctime and Justice; Datesman, S., Scarpitti, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Visher, C.A. Gender, police arrest decisions, and notions of chivalry. Criminology 1983, 21, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, O. Criminality of Women; AS Barnes and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Broverman, I.K.; Vogel, S.R.; Broverman, D.M.; Clarkson, F.E.; Rosenkrantz, P.S. Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. J. Soc. Issues 1972, 28, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. The ambivalent sexism inventow: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waaijer, C.J.; Sonneveld, H.; Buitendijk, S.E.; van Bochove, C.A.; van der Weijden, I.C. The role of gender in the employment, career perception and research performance of recent PhD graduates from Dutch universities. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A., Jr. Women and Minority Faculty in the Academic Workplace: Recruitment, Retention, and Academic Culture; (Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series); ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, L.S. Conceptualizing faculty job satisfaction: Components, theories, and outcomes. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2000, 27, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, T.A.; Umbach, P.D. The effects of faculty demographic characteristics and disciplinary context on dimensions of job satisfaction. Res. High. Educ. 2008, 49, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, K.L.; Rogers, S.M. Gender differences in faculty member job satisfaction: Equity forestalled? Res. High. Educ. 2018, 59, 1105–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A.; Cianci, E.; Mastore, P.; Gozzoli, C. Protective and risk factors of Italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzoli, C.; De Leo, A. Receiving asylum seekers: Risks and resources of professionals. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920920312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Organizational identity. Res. Organ. Behav. 1985, 7, 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K.; Reader, G.; Kendall, P.L. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Dducation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Pease, J. Faculty influence and professional participation of doctoral students. Sociol. Inq. 1967, 37, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, J.C.; Stein, E.L. Socialization of doctoral students to academic norms. Res. High. Educ. 2003, 44, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Vallerand, R.J.; Amoura, S.; Baldes, B. Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, E.; Mageau, G.A. The importance of perceived autonomy support for the psychological health and work satisfaction of health professionals: Not only supervisors count, colleagues too! Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Walker, L. Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis; L. Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with equity theory? In Social Exchange; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, J.; Noblet, A.; Demir, D.; Steane, P. Supervisors are Central to Work Characteristics Affecting Nurse Outcomes. J. Nurs. Sch. 2009, 41, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, B.; van Laar, C.; Ellemers, N. The queen bee phenomenon: Why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; King, E.B.; Rogelberg, S.G.; Kulich, C.; Gentry, W.A. Perceptions of supervisor support: Resolving paradoxical patterns across gender and race. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsons, H. Recognition for group work: Gender differences in academia. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, H.P.; Browning, L. Gender equality in academia: A critical reflection. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2015, 37, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew, E.; Zamudio, C.; Meng, H.M. Beyond perception: The role of gender across marketing scholars’ careers, in reply to Galak and Kahn. Mark. Lett. 2021, 32, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, S.J. Gender and the career choice process: The role of biased self-assessments. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 106, 1691–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González Ramos, A.M.; Fernández Palacín, F.; Muñoz Márquez, M. Do men and women perform academic work differently? Tert. Educ. Manag. 2015, 21, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ANAC. Autorità Nazionale Anticorruzione. Modelli per la Realizzazione di Indagini sul Benessere Organizzativo, sul Grado di Condivisione del Sistema di Valutazione e Sulla Valutazione del Superiore Gerarchico. 2013. Available online: http://www.anticorruzione.it/portal/public/classic/home/_RisultatoRicerca?id=ed0d622e0a77804266c291bc669a1d05&search=benessere (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Cortese, C.G.; Emanuel, F.; Colombo, L.; Bonaudo, M.; Politano, G.; Ripa, F.; Gianino, M.M. The Evaluation of Organizational Well-Being in An Italian Teaching Hospital Using the ANAC Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Levene, H. Robust Tests for Equality of Variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics; Olkin, I., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Skakni, I.; Calatrava Moreno, M.D.C.; Seuba, M.C.; McAlpine, L. Hanging tough: Post-PhD researchers dealing with career uncertainty. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 1489–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatemarco, A.; Dell’Anno, R. Italian Reform of the academic recruitment system. An appraisal of ANVUR and CUN benchmarks for assessing candidates and commissioners. Rivista Italiana degli Economisti 2012, 17, 441–480. [Google Scholar]

| ANAC Constructs | Alpha | Number of the Items | Sample Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and security | 0.643 | 5 | My university is a safe place to work. I have received appropriate information and training on the risks associated with my work activity and on the relevant prevention and protection measures during the COVID emergency (modified). The characteristics of my university (spaces, workstations, brightness, noise, etc.) are satisfactory with respect to my research needs. I have been subjected to mobbing (formal or de facto demotion, exclusion of decision-making autonomy, isolation, exclusion from the flow of information, unjustified unequal treatment, exasperated forms of control, …). I am subjected to harassment in the form of words or behavior, likely to undermine my dignity and create a negative climate in the workplace. |

| Discrimination | 0.684 | 8 | I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my role as a doctoral student (modified). I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my political orientation. I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my religion. I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my ethnicity and/or gender. I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my language. My age constitutes an obstacle to my development at work. I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my sexual orientation. I am treated fairly and with respect in relation to my disability |

| Fairness | 0.866 | 5 | I believe there is fairness in the allocation of the workload. I believe there is fairness in the distribution of responsibilities. I think there is a balanced relationship between the work required and my pay. I consider that there is a balance in the way pay is differentiated in relation to the quantity and quality of work done. Decisions concerning work are made by my supervisor in an impartial manner (adapted). |

| Career/professional development | 0.903 | 5 | In my research group, everyone’s professional development path is well defined and clear. I believe that real career opportunities at my university are linked to merit. My university gives the opportunity to develop the skills and aptitudes of individuals in relation to the requirements of different roles. My current role is appropriate to my professional profile. I am satisfied with my professional career at my university (adapted). |

| Job autonomy | 0.85 | 5 | I know what is expected of my research work. I have the necessary skills to carry out my research work. I have the resources and tools necessary to carry out my research work. I have an adequate level of autonomy to carry out my research work. My research work gives me a sense of personal fulfilment. |

| Sense of belonging | 0.912 | 5 | I am proud when I tell someone that I work at my university. I am proud when my institution achieves a good result. I am sorry if someone speaks badly about my institution. The values and behaviors practiced in my university are consistent with my personal values. I would change my university if I could. |

| Goal sharing | 0.936 | 4 | I know my university’s strategies. I share the strategic objectives of my university. I am clear about my university’s achievements. I am clear about the contribution of my work to the achievement of the university’s objectives. |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health and safety | 4.61 | 0.94 | ||||||||||

| 2. Discrimination | 4.41 | 0.60 | 0.37 ** | |||||||||

| [0.21, 0.52] | ||||||||||||

| 3. Fairness | 3.55 | 1.27 | 0.61 ** | 0.45 ** | ||||||||

| [0.48, 0.71] | [0.29, 0.58] | |||||||||||

| 4. Career | 3.55 | 1.30 | 0.67 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.75 ** | |||||||

| [0.56, 0.76] | [0.26, 0.56] | [0.66, 0.82] | ||||||||||

| 5. Sense of belonging | 4.26 | 1.28 | 0.57 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.73 ** | ||||||

| [0.43, 0.68] | [0.20, 0.51] | [0.41, 0.66] | [0.63, 0.80] | |||||||||

| 6. Goals sharing | 4.11 | 1.51 | 0.59 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.60 ** | |||||

| [0.43, 0.71] | [0.11, 0.50] | [0.35, 0.66] | [0.54, 0.78] | [0.45, 0.72] | ||||||||

| 7. Job autonomy | 4.21 | 1.16 | 0.46 ** | 0.16 | 0.56 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.59 ** | ||||

| [0.31, 0.59] | [0.02, 0.33] | [0.42, 0.67] | [0.55, 0.75] | [0.40, 0.65] | [0.43, 0.72] | |||||||

| 8. a Gender | 1.58 | 0.50 | −0.21 * | 0.08 | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.16 | −0.24 ** | |||

| [0.37, 0.03] | [0.10, 0.26] | [0.30, 0.05] | [0.31, 0.04] | [0.24, 0.12] | [0.36, 0.06] | [−0.40, 0.06] | ||||||

| 9. Time | 4.04 | 1.47 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.26 ** | 0.19 * | 0.21 * | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ||

| [−0.04, 0.31] | [−0.00, 0.35] | [0.08, 0.41] | [0.01, 0.35] | [0.03, 0.38] | [−0.07, 0.35] | [−0.06, 0.29] | [−0.12, 0.23] | |||||

| 10. b University of northen Italy | 0.31 | 0.46 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.21 * | −0.27 ** | −0.21 * | −0.17 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.20 * | |

| [−0.28, 0.07] | [−0.30, 0.05] | [−0.38, 0.04] | [−0.43, 0.10] | [−0.37, 0.03] | [−0.37, 0.05] | [−0.29, 0.06] | [−0.30, 0.06] | [−0.37, 0.03] | ||||

| 11. b University of central Italy | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.24 ** | 0.18 * | 0.31 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.32 ** | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.24 ** |

| [0.07, 0.40] | [0.00, 0.35] | [0.14, 0.46] | [0.09, 0.42] | [0.07, 0.41] | [0.13, 0.52] | [0.15, 0.47] | [−0.18, 0.17] | [−0.15, 0.20] | [−0.40, 0.06] |

| Predictor | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial η2 | Partial η2 90% CI [LL, UL] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and safety at work | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 201.13 | 1 | 201.13 | 248.65 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 5.08 | 1 | 5.08 | 6.28 | 0.014 | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.13] |

| Time | 1.85 | 1 | 1.85 | 2.28 | 0.134 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| a University of northern Italy | 0.27 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.565 | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.04] |

| a University of central Italy | 5.12 | 1 | 5.12 | 6.33 | 0.013 | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.13] |

| Lack of discrimination | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 167.64 | 1 | 167.64 | 481.28 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 0.21 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.441 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.05] |

| Time | 1.07 | 1 | 1.07 | 3.07 | 0.082 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| a University of northern Italy | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.644 | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.03] |

| a University of central Italy | 1.12 | 1 | 1.12 | 3.22 | 0.075 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Fairness | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 87.85 | 1 | 87.85 | 65.19 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 4.85 | 1 | 4.85 | 3.60 | 0.060 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.10] |

| Time | 10.04 | 1 | 10.04 | 7.45 | 0.007 | 0.06 | [0.01, 0.14] |

| a University of northern Italy | 2.53 | 1 | 2.53 | 1.88 | 0.173 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| a University of central Italy | 13.57 | 1 | 13.57 | 10.07 | 0.002 | 0.08 | [0.02, 0.17] |

| Career/Professional development | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 114.45 | 1 | 114.45 | 78.93 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 5.77 | 1 | 5.77 | 3.98 | 0.048 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.10] |

| Time | 4.25 | 1 | 4.25 | 2.93 | 0.089 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| a University of northern Italy | 8.03 | 1 | 8.03 | 5.54 | 0.020 | 0.05 | [0.00, 0.12] |

| a University of central Italy | 8.35 | 1 | 8.35 | 5.76 | 0.018 | 0.05 | [0.00, 0.12] |

| Sense of belonging | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 142.58 | 1 | 142.58 | 95.71 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 1.40 | 1 | 1.40 | 0.94 | 0.334 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.05] |

| Time | 6.41 | 1 | 6.41 | 4.30 | 0.040 | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.11] |

| a University of northern Italy | 3.01 | 1 | 3.01 | 2.02 | 0.158 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| a University of central Italy | 8.05 | 1 | 8.05 | 5.40 | 0.022 | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.12] |

| Goals sharing | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 106.30 | 1 | 106.30 | 52.85 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 4.02 | 1 | 4.02 | 2.00 | 0.162 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.11] |

| Time | 2.26 | 1 | 2.26 | 1.13 | 0.292 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| a University of northern Italy | 1.90 | 1 | 1.90 | 0.94 | 0.334 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| a University of central Italy | 15.11 | 1 | 15.11 | 7.51 | 0.008 | 0.09 | [0.01, 0.20] |

| Job autonomy | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 168.50 | 1 | 168.50 | 147.77 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 9.60 | 1 | 9.60 | 8.42 | 0.004 | 0.07 | [0.01, 0.15] |

| Time | 2.08 | 1 | 2.08 | 1.82 | 0.180 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| a University of northern Italy | 0.34 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.587 | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.04] |

| a University of central Italy | 14.32 | 1 | 14.32 | 12.56 | 0.001 | 0.10 | [0.03, 0.19] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corvino, C.; De Leo, A.; Parise, M.; Buscicchio, G. Organizational Well-Being of Italian Doctoral Students: Is Academia Sustainable When It Comes to Gender Equality? Sustainability 2022, 14, 6425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116425

Corvino C, De Leo A, Parise M, Buscicchio G. Organizational Well-Being of Italian Doctoral Students: Is Academia Sustainable When It Comes to Gender Equality? Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116425

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorvino, Chiara, Amalia De Leo, Miriam Parise, and Giulia Buscicchio. 2022. "Organizational Well-Being of Italian Doctoral Students: Is Academia Sustainable When It Comes to Gender Equality?" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116425

APA StyleCorvino, C., De Leo, A., Parise, M., & Buscicchio, G. (2022). Organizational Well-Being of Italian Doctoral Students: Is Academia Sustainable When It Comes to Gender Equality? Sustainability, 14(11), 6425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116425