Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs: Learning Orientation and Performance Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

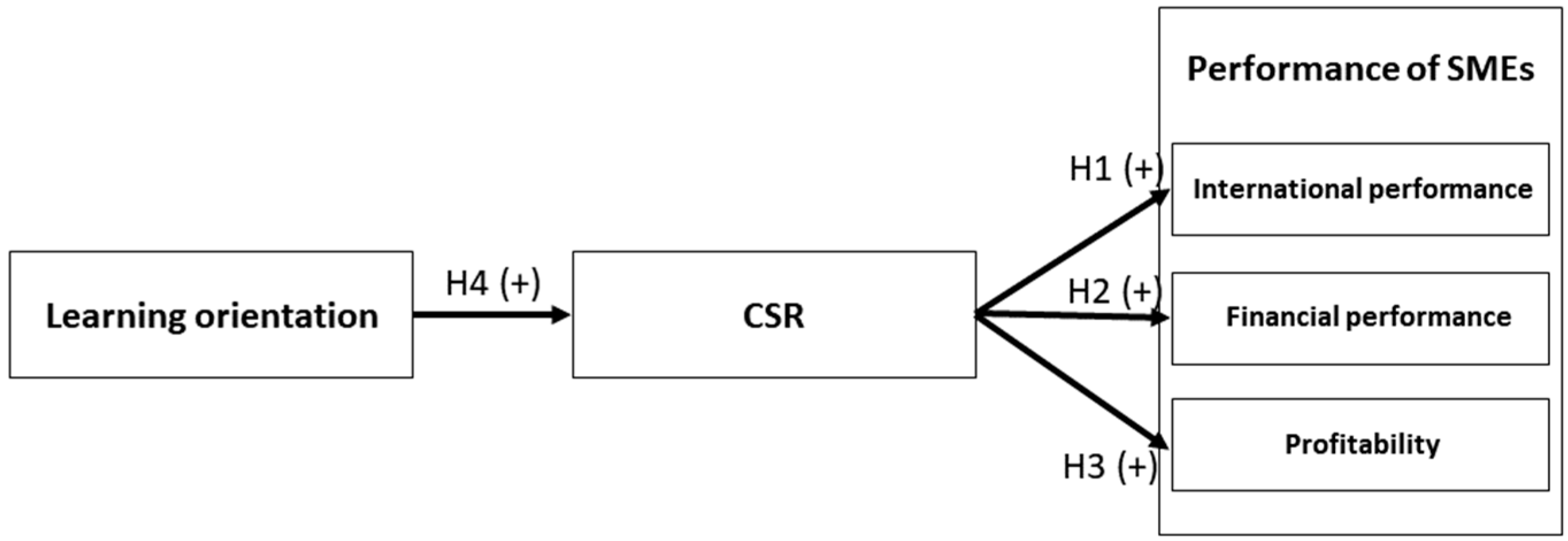

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Impact of CSR on the Performance of SMEs

2.2. Strategic Orientations and CSR

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measure Development

- We participate in activities whose goal is environmental protection.

- We invest to create a better life for future generations.

- We execute specific programmes, whose goal is to minimise the impact of our company on the natural environment.

- We aim for sustainable growth which also takes into account future generations.

- Managers agree that our firm’s ability to learn is the key to our competitive advantage.

- The sense around here is that employee learning is an investment, not an expense.

- Learning in my organization is seen as a key commodity necessary to guarantee organizational survival.

- Managers encourage employees to “think outside of the box”.

- Original ideas are highly valued in this organization.

- Generally speaking, we are satisfied with our success in international markets

- We have reached the turnover goals we set for internationalization.

- We have reached the market share goals we set for internationalization

- Internationalization has had a positive effect on the profitability of our company.

- Internationalization has had a positive effect on the image of our company.

- Internationalization has had a positive effect on the development of our know-how.

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable Development and Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Directions. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinaro, V.; Liu, Y.; Lee, T.-R.; Jiun, S.; Poesche, J. Extracting Key Factors for Sustainable Development of Enterprises: Case Study of SMEs in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1152–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uzhegova, M.; Torkkeli, L.; Salojärvi, H.; Saarenketo, S. CSR-Driven Entrepreneurial Internationalization: Evidence of Firm-Specific Advantages in International Performance of SMEs. In Emerging Issues in Global Marketing: A Shifting Paradigm; Agarwal, J., Wu, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 257–289. ISBN 978-3-319-74129-1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Executive Agency for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Uptake of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) by European SMEs and Start-Ups: Final Report; Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkova, D.; Bengtsson, E.; Durst, S. Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. SMEs and CSR: An Approach to CSR in Their Own Words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Perrini, F. CSR in SMEs: Do SMEs Matter for the CSR Agenda? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzhegova, M.; Torkkeli, L.; Saarenketo, S. Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs: Implications on Competitive PerformanceDate Submitted: October 12, 2017 Revised Version Accepted after Double Blind Review: December 15, 2018. Mrev Manag. Rev. 2019, 30, 232–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Mihai, L.S. An Integrated Framework on the Sustainability of SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammann, E.-M.; Habisch, A.; Pechlaner, H. Values That Create Value: Socially Responsible Business Practices in SMEs—Empirical Evidence from German Companies. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D.; Gartner, J.; Hakala, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Snellman, K. The Dark Side of Sustainability Orientation for SME Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, e00198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.; Torkkeli, L.; Sainio, L.-M. Service Innovation and Internationalization in SMEs: Antecedents and Profitability Outcomes. J. Int. Entrep. 2020, 18, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Ramos-Escobar, E.A. Organizational Learning and Corporate Social Responsibility Drivers of Performance in SMEs in Northwestern Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Isabel Sánchez-Hernández, M. Structural Analysis of the Strategic Orientation to Environmental Protection in SMEs. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nejati, M.; Quazi, A.; Amran, A.; Ahmad, N.H. Social Responsibility and Performance: Does Strategic Orientation Matter for Small Businesses? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. The Synergistic Effect of Market Orientation and Learning Orientation on Organizational Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F. SMEs and CSR Theory: Evidence and Implications from an Italian Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbmann, U. Establishing Strategic CSR in SMEs: An Austrian CSR Quality Seal to Substantiate the Strategic CSR Performance. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Maksimov, V. Achieving Legitimacy through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case of Emerging Economy Firms. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Ivanova, O. Signalling Legitimacy in Global Contexts: The Case of Small Wine Producers in Bulgaria. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2017, 29, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, A.; Adeleye, B.N.; Adusei, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Evidence from U.S Tech Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, M.W. Global Competitiveness: Born Global. McKinsey Q. 1993, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk, A.; van Tulder, R. International Business, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoian, C.; Gilman, M. Corporate Social Responsibility That “Pays”: A Strategic Approach to CSR for SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerald Publishing Limited. Is Some CSR Just CEOs’ Selfishness? Study Rejects Suggestions of Reputation-Building. Strateg. Dir. 2017, 33, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, R.; Le Bas, C.; Mothe, C.; Poussing, N. Strategic CSR for Innovation in SMEs: Does Diversity Matter? Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. Corporate Social Responsibility in Ireland: Barriers and Opportunities Experienced by SMEs When Undertaking CSR. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancheswaran, A.; Gautam, V. CSR in SMEs: Exploring a Marketing Correlation in Indian SMEs. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2011, 24, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrizos, S.; Apospori, E.; Carrigan, M.; Jones, R. Is CSR the Panacea for SMEs? A Study of Socially Responsible SMEs during Economic Crisis. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Chatterjee, P.; Demir, K.D.; Turut, O. When and How Is Corporate Social Responsibility Profitable? J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Børing, P. The Relationship between Firm Productivity, Firm Size and CSR Objectives for Innovations. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2019, 9, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falck, O.; Heblich, S. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing Well by Doing Good. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Johns, R. The Effect of Environmental CSR Issues on Corporate/Brand Reputation and Corporate Profitability. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Xuereb, J.-M. Strategic Orientation of the Firm and New Product Performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, C.H.; Sinha, R.K.; Kumar, A. Market Orientation and Alternative Strategic Orientations: A Longitudinal Assessment of Performance Implications. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar Strengths and Relational Attributes of SMEs in the Context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, T.; Nagy, G.; Hirvonen, S.; Reijonen, H.; Pasanen, M. The Effect of Strategic Orientations on Business Performance in SMEs. Int. Mark. Rev. 2013, 30, 510–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Maksimov, V.; Gilbert, B.A.; Fernhaber, S.A. Entrepreneurial Orientation and International Scope: The Differential Roles of Innovativeness, Proactiveness, and Risk-Taking. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amin, M. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Orientation and Learning Orientation on SMEs’ Performance: An SEM-PLS Approach. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2015, 8, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keskin, H. Market Orientation, Learning Orientation, and Innovation Capabilities in SMEs. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2006, 9, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Beers, P.J. Understanding and Governing Learning in Sustainability Transitions: A Review. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.A.; Pett, T.L.; Ring, J.K. Small Firm Growth as a Function of Both Learning Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2015, 21, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Sun, X.; Yang, J. Green Learning Orientation, Green Knowledge Acquisition and Ambidextrous Green Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, G.; Su, K. The Fit between Environmental Management Systems and Organisational Learning Orientation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 2901–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and Procedural Remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.V.; Coviello, N.; Tang, Y.K. International Entrepreneurship Research (1989–2009): A Domain Ontology and Thematic Analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 632–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, I.K.; Akoorie, M.E.M.; Sinha, P. International Entrepreneurship: A Critical Analysis of Studies in the Past Two Decades and Future Directions for Research. J. Int. Entrep. 2012, 10, 279–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkkonen, L.; Quarshie, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Finland: Origins, Characteristics, and Trends; Palgrave pivot; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-17435-4. [Google Scholar]

- Torkkeli, L.; Saarenketo, S.; Nummela, N. The Development of Network Competence in an Internationalized SME. In Handbook on International Alliance and Network Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 459–494. ISBN 978-1-78347-548-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, W.W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.-H.S.; Wu, M.-S.S.; Liu, G. Proactive Environmental Strategy, Foreign Institutional Pressures, and Internationalization of Chinese SMEs. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Campbell-Hunt, C. A Strategic Approach to Internationalization: A Traditional versus a “Born-Global” Approach. J. Int. Mark. 2004, 12, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. Business Relationship Learning and Commitment in the Internationalization Process. J. Int. Entrep. 2003, 1, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, A.; Nummela, N.; Puumalainen, K.; Saarenketo, S. Strategic Orientations of Born Globals—Do They Really Matter? J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, F.; Lindsay, N.J.; Shoham, A. Entrepreneurial, Market, and Learning Orientations and International Entrepreneurial Business Venture Performance in South African Firms. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzhegova, M.; Torkkeli, L.; Ivanova-Gongne, M. The Role of Responsible Business Practices in International Business Relationships Between SMEs from Developed and Emerging Economies. In International Business and Emerging Economy Firms: Volume II: European and African Perspectives; Larimo, J.A., Marinov, M.A., Marinova, S.T., Leposky, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–59. ISBN 978-3-030-27285-2. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitratos, P.; Amorós, J.E.; Etchebarne, M.S.; Felzensztein, C. Micro-Multinational or Not? International Entrepreneurship, Networking and Learning Effects. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisalo, T.; Leppäaho, T. Learning in International New Ventures: A Systematic Review. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, S.; Naldi, L.; Hunter, E. Market Orientation as Determinant of Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Investigation on SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2006, 2, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.I.M.A.S.; Ferreira, J.J.M.; Lobo, C.A.; Raposo, M. The Impact of Market Orientation on the Internationalisation of SMEs. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2020, 30, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, A.; Hyder, A.S.; Chowdhury, E.H. Market-Oriented CSR Implementation in SMEs with Sustainable Innovations: An Action Research Approach. Balt. J. Manag. 2020, 15, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Long, X.; Li, L.; Kong, L.; Zhu, X.; Liang, H. Engagement Factors for Waste Sorting in China: The Mediating Effect of Satisfaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Long, X.; Salman, M. Did the 2014 Nanjing Youth Olympic Games Enhance Environmental Efficiency? New Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | CSR | Learning Orientation | International Performance | Performance | Profitability | Firm Size [Employees] | Firm Age [Years] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 1 | ||||||

| Learning Orientation | 0.25 ** | 1 | |||||

| International Performance | 0.43 ** | 0.22 * | 1 | ||||

| Performance | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 1 | |||

| Profitability | 0.22 | 0.15 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 1 | ||

| Firm size [employees] | 0.18 * | 0.03 | 0.26 * | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1 | |

| Firm age [years] | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.25 ** | 1 |

| Min | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | −4,769,809.00 | 1 | 2 |

| Mean | 4.28 | 5.38 | 4.19 | 6.36 | 681,620.37 | 48.71 | 31.28 |

| Max | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 | 12,287,463,00 | 240 | 144 |

| St.Dev. | 1.41 | 0.99 | 1.45 | 2.34 | 1,723,422.747 | 47.02 | 24.34 |

| Control Model for H1 | International Performance (H1) | Control Model for H2 | Performance (H2) | Control Model for H3 | Profitability (H3) | Control Model for H4 | Learning Orientation (H4) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Firm size [employees] | 0.23 | 2.11 * | 0.17 | 1.65 | −0.01 | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.36 | −0.02 | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.33 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Firm age [years] | 0.13 | 1.25 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.06 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.19 | 1.52 | 0.17 | 1.35 | −0.07 | −0.79 | −0.10 | −1.08 |

| CSR | 0.39 | 3.90 ** | 0.16 | 1.77 | 0.16 | 1.30 | 0.26 | 2.97 ** | ||||||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.06 | 0.20 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| F | 3.89 * | 8.03 ** | 0.26 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 0.35 | 3.19 * | ||||||||

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| H1. The higher the CSR of an SME, the higher its international performance | Supported |

| H2. The higher the CSR of an SME, the higher its overall performance | Not supported |

| H3. The higher CSR in SMEs will result in increased profitability. | Not supported |

| H4. The higher the learning orientation of the SMEs, the higher their CSR. | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torkkeli, L.; Durst, S. Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs: Learning Orientation and Performance Outcomes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116387

Torkkeli L, Durst S. Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs: Learning Orientation and Performance Outcomes. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116387

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorkkeli, Lasse, and Susanne Durst. 2022. "Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs: Learning Orientation and Performance Outcomes" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116387

APA StyleTorkkeli, L., & Durst, S. (2022). Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs: Learning Orientation and Performance Outcomes. Sustainability, 14(11), 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116387