1. Introduction

Education is a basic human right, and it is central to achieving sustainable development. For individuals, education can increase the probability of employment, increase labor productivity and income, and reduce poverty [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, education has non-monetary benefits. Education can bring about better health, more engaged citizenship, as well as better life choices [

4,

5,

6]. For society, first, education generates material benefits by increasing productivity, boosting economic growth, and promoting poverty reduction and long-term development [

7,

8,

9]. Second, education brings non-material benefits to social development through increasing social mobility, citizen participation, better institutional provision, and social cohesion [

10,

11]. Hence, improving the level of individual education is crucial to sustainable development, both for individuals and society.

Family education investment plays an important role in improving the educational levels of offspring. The public sector is undoubtedly an important provider of educational investment [

12], but for the vast number of developing and less developed countries, the public sector has limited financial resources and mainly invests in areas that promote rapid economic growth in the short term [

13]. Often, it can only guarantee the universalization of basic education and education fairness. Therefore, family education investment from the private sector is important for high-quality human capital accumulation [

14]. It is the parents who have the right to decide whether to invest in their children’s education when the children are young. The children themselves are more in a passive position. If parents pay attention to children’s education, increase their investment in their children’s education, and let their children receive high-quality education, the final education level of children will be higher; on the contrary, less investment in education will affect the quality of education children receive and ultimately have a negative impact on the children’s educational achievement.

Internal rural–urban migration is considered one of the main ways to escape poverty and a primary feature of economic development in developing countries [

15]. Migration out of agriculture is generally associated with improved living standards of migrant families. Increases in out-migration can lead to increased investment in assets related to agricultural production and other investments in source communities [

16]. The study of migration as an economic process has a long history [

17,

18].

However, the effects of migration on source households and family members can be complex. For instance, it is common in developing countries for one or both parents to migrate out for work while leaving their children home with one parent or other relatives [

19,

20]. When children are left behind, they risk facing negative consequences for their education [

21]. In recent years, researchers have raised concerns about the potential negative effects of migration on the education of the children who are left behind in rural areas [

22].

In China, with the continuous increase in the scale of rural migrant workers, the number of left-behind children has also increased rapidly [

21]. In China, left-behind children are children under the age of 18, who live in their original domicile, but do not live together with their parents, as either one parent or both parents have migrated. They are also called LBC [

23]. Data show that the number of rural residents who went out to work has increased from 20 million in 1990 to 174.3 million in 2019 in China (Data in 1990 come from the National Population Census. Data in 2019 come from the Monitoring Reports of Rural Migrant Workers. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China), and the rural–urban migration population has increased by nearly 8eight times in less than 30 years. The number of left-behind children also increased from 26.99 million in 2000 to 40.51 million in 2015 in China (Data in 2000 come from Population Censuses. Data in 2015 come from the 1% National Population Sample Survey (also called “mini-census”). The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China). As a vulnerable group, the education and health of LBC have received extensive attention from the government, media, and academic researchers.

Existing studies on the education of LBC mainly focus on academic performance and academic achievement, but there is a lack of research on the educational investment behavior of parents of LBC. For example, studies have shown that rural–urban migration has a negative impact on LBC’s academic performance in Uganda and China. Some studies also found that rural–urban migration has a negative impact on children’s years of education in Mexico and China [

21,

23]. However, little attention has been paid to how migration affects parents’ educational investment in LBC. Research on this issue can further deepen the understanding the reasons behind the impact on children’s educational outcomes.

China is a compelling place to study internal migration and its consequences for LBC in rural areas for two reasons. First, China has unprecedented labor migration, with dramatic increases in the number of migrants in the past decades. Second, the left-behind population in China is to a large extent an outcome of institutional processes [

24], in particular, the long-standing bifurcated social institution, which is usually called hukou (the residential registration system). The system categorizes all citizens into a rural–urban dichotomy (rural residents are registered with rural hukou; urban residents are registered with urban huko), which has led to various structural and social barriers in migrants’ access to public services and the labor market in urban areas.

So, the overall goal of this study is to examine the effect of internal migration on LBC’s educational investment in China. This paper uses the 2012 data from Peking University Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS) to answer the above questions. On the basis of theoretical analysis, the paper first uses the OLS model for benchmark regression, and then uses the double robust model to solve possible endogeneity problems. Additionally, the article tests the robustness of its results by replacing the control variable, replacing the dependent variable, and replacing the estimate model. This paper not only provides empirical support for a deep understanding of the impact of internal rural–urban migration on educational investment in LBC, but also helps to understand how urbanization influences people’s perceptions and behaviors. In addition, this study has significance for formulating relevant policies to improve the level of rural human capital, expand the middle-income group, and achieve the goal of common prosperity for China. In the end, the lessons learned from China are valuable for other developing countries with large numbers of rural citizens migrating to cities.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 first analyzes family educational investment theoretically and then develops our hypothesis.

Section 3 presents the research design, and

Section 4 reports the estimated results with primary regression, endogeneity treatment with Inverse Probability Weighted Regression Adjustment model (IPWRA) and Augmented Inverse Probability Weighting model (AIPW), robustness test, impact mechanism analysis, and heterogeneity discussion.

Section 5 provides the conclusion, possible policy recommendations, as well as research limitations.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

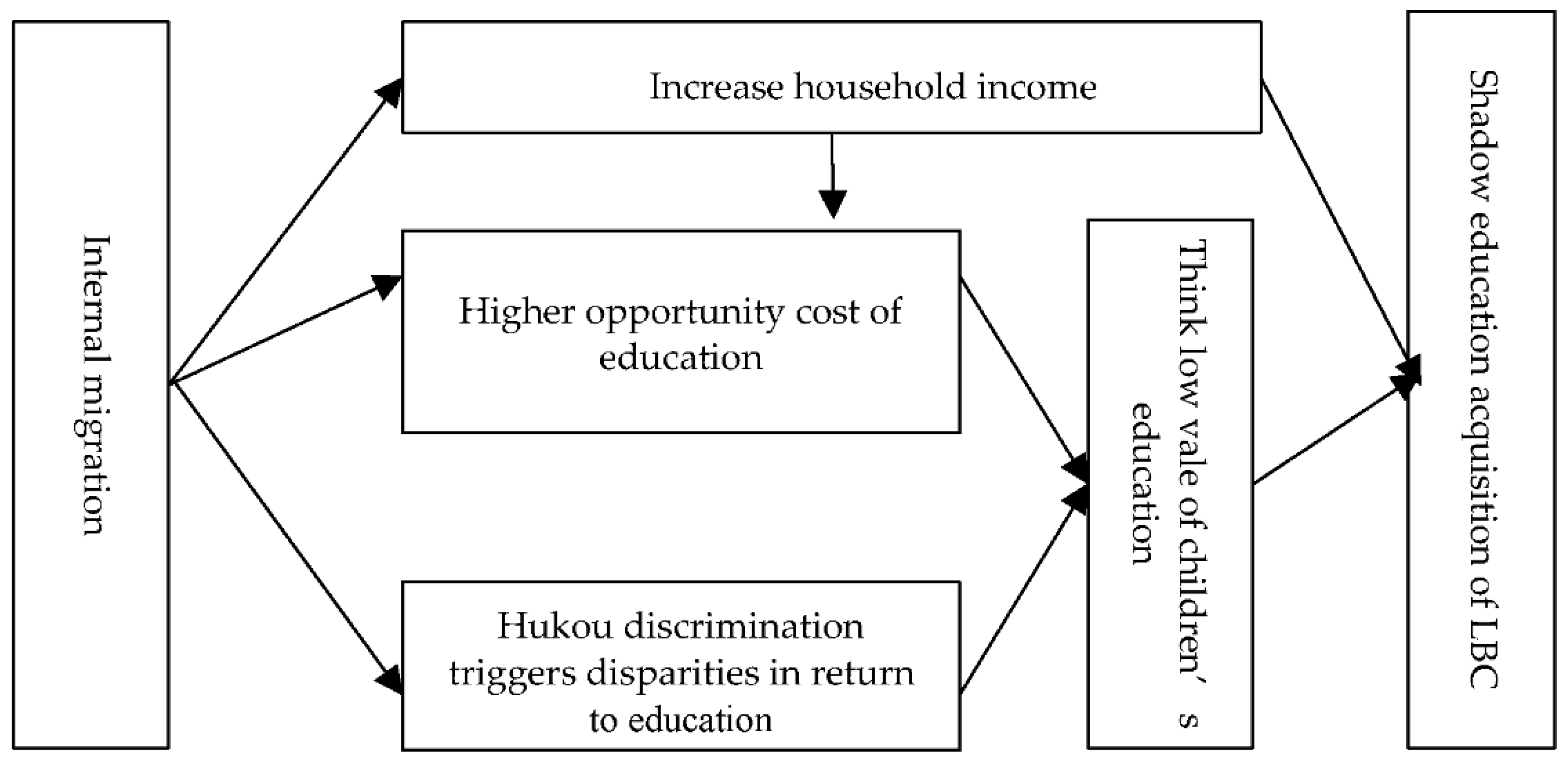

Based on the data from the China Family Panel Studies in 2012, this article uses the IPWRA model and AIPW model to solve possible endogeneity problems on the basis of the OLS model. Then, we conduct a series of robust tests. The estimated results show that internal migration significantly reduces the level of educational investment for LBC in China. Mechanism analysis shows that, on the one hand, internal migration increases family income, so that the family has more resources to invest in the children’s education, but at the same time, it reduces family’s awareness of the necessity of investing in children’s education, thereby reducing the need for investing in children’s education. The result of the combined effect of these two factors is that internal migration significantly reduces the level of children’s educational investment. Heterogeneity analysis found that LBC in families with both parents going out had the greatest negative impact, followed by only fathers going out, and families in which only mothers going out had no significant impact; the negative impact of going out across provinces was greater than that of going out inside the province. The negative impact on girls is greater than on boys. The negative impact on children in junior high school is greater than that on children in primary school.

Different from existing research, this paper answers the question of how rural–urban population migration affects the educational investment behavior of parents toward their children. This provides a channel for thinking about the impact of rural–urban migration on the results of offspring human capital accumulation, and further enriches the research on the impact of migration on human capital accumulation and investment. At the same time, it also provides evidence from China for understanding the impact of migration on human capital accumulation from the perspective of international comparison.

From a practical point of view, the results of this paper show that, on the one hand, it is necessary to see the short-term positive effect of increasing rural household income and improving material welfare for internal migration. However, the possible long-term negative effects cannot be ignored—that is, internal migration may further lead to a decrease in educational investment in children and thus have a negative impact on children’s human capital accumulation. For China, this will undoubtedly challenge the goal of achieving common prosperity. Therefore, further eliminating discrimination in the labor market caused by household registration status and improving the quality of education in rural public schools are optimal policy tools to promote educational equity and achieve common prosperity. The research in this paper also provides a reference for other developing countries to assess the impact of rural–urban migration on human capital accumulation in their own countries.

There are some limitations which require further research. First, the endogeneity problem can be further improved. Although we adopt the IPWRA and AIPW model to solve endogeneity problems as well as a series of robust tests to test the robustness of our results, this could be achieved better with panel data. In this paper, due to the limitations, we can only use data from 2012. Therefore, there may be bias due to unobservable variables that do not change over time. Hence, future researchers are advised to use a panel data to better deal with endogeneity problems. Secondly, this study only uses data from China. It would be interesting to use data from other developing countries for future research to make a comparison analysis.Lastly, for a more detailed study, future research can analyze heterogeneity influence with different migration durations and different city hierarchies.