Abstract

The research presented is framed in the context of educational technology (ET), and specifically in its use as a support tool for students with specific learning difficulties (SLD). This is descriptive quantitative research, the objective of which is to know what students know about the use of educational technology, the perceived usefulness of educational applications, and the use of educational technology as support for students with specific learning difficulties. In order to answer this question, a data-collection instrument was designed that included an ad hoc questionnaire made up of three blocks to evaluate the use of ET, the perceived usefulness of educational applications, as well as ET as a support for students with SLD. The participating sample is made up of students from different teacher training degrees of the Faculty of Education of the University of Burgos (n = 130). After the descriptive analysis was carried out, the results that were obtained allowed us to conclude that ET is an excellent proposal for the classroom, and that, due to its adaptability, it can, and should, be a frequent resource for achieving educational objectives, and especially as support for students with SLD.

1. Introduction

The development of today’s educational society implies new competences from different perspectives, and so the educational field needs the involvement of new technologies to guide and direct a new educational paradigm that provides personalized responses and that focuses learning on the development of the student’s potential.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) allow the development of keys that will enable the student to be seen as a coprotagonist in their learning in order to: increase motivation to awaken interest in learning and understanding; lighten the immediacy of the transmission and reception of information; and provide flexibility in the pace and time of learning [1].

For the UNESCO [2], inclusive education is a process of strengthening the capacity of the education system to reach all students.

An inclusive educational system can only be created if the curricular contents are adapted to a more diverse reality.

Following Benítez, Peral, and Hermida [3], to guarantee the access of people with difficulties to these contexts, support is essential (that is, an organization of the environments that makes them inclusive). New technologies have not only become a requirement for participation in society, but also an important facilitating environment. For Camacho, Vera, and Méndez [4], they fulfill adaptive functions that involve different processes of the elaboration, communication and development of school information.

2. Literature Review

Attention to diversity is the protagonist of educational change and, therefore, ICT, as an adaptive methodology, enables the development between the two, and the increase in related educational technology so that it is more numerous every day [5]. There is a great deal of research and a number of technological tools that seek to develop educational inclusion [6,7,8]. Currently, emerging technologies such as Augmented Reality (AR), the Semantic Web, and Virtual Reality (VR) are fundamental in the development of this new context [9].

In this sense, the improvement in the learner’s quality of life and interaction with the educational system are greatly enhanced by the use of technology, and the learner, whose needs may hinder full inclusion, is supported by technology in the different areas of his or her life [10].

This chapter shows a review of the literature on the subject that is addressed in relation to educational technology, specific learning difficulties, as well as the relationship between both concepts. Finally, a review of educational applications that can be used as an adaptive curricular vehicle for intervention with students with specific learning difficulties is included.

2.1. Educational Technology

This educational-technological evolution, and the growing presence in schools, imply new lines of research and the implementation of new challenges, as they open up an enormous field of action within inclusive education. The implementation of audiovisual technology is one of the most widely used for the improvement in learning difficulties and disability, and for the following reasons [10,11,12]:

- Educational technology is an important support within the most diverse disabilities, from sensory to cognitive;

- Educational technology personalises needs, and therefore creates self-sufficient learners;

- Educational technology fosters communicative interaction between students and teachers;

- Educational technology facilitates the acquisition of content in less time;

- Some applications and programs help diagnosis, and always as a means of support and used by a specialist;

- Educational technology is based on multisensory models;

- Educational technology helps in the inclusion of people with disabilities in the workplace;

- Educational technology opens new scientific and cultural horizons to students;

- Educational technology enhances self-esteem, as pupils feel more capable.

The role of the educator is essential to determining the types of tools that are needed for the optimal achievement of objectives, and this selection is even more important if it involves people with disabilities or learning difficulties. Therefore, the selection and knowledge of the different technological solutions, characteristics, adaptabilities, etc., are an important part of the selection and decision-making process [12].

For learners with special educational needs, the following should be considered [10]:

- The type of disability determines the use of one or another technological proposal;

- The degree of disability is a determining factor in this selection;

- It is necessary to determine not only the type of software, but also the hardware, that may be necessary to carry out the adaptations;

- Materials can and must be adapted, supplemented, and combined on numerous occasions;

- Interdisciplinarity in the design of materials and their adaptation is very important. Therefore, different professionals from different perspectives must collaborate.

In the field of educational technology, there is a great deal of research that seeks to develop educational inclusion [6,7,8]. Currently, emerging technologies, such as Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), the Semantic Web, or Artificial Intelligence (AI), are fundamental in the development of this new context [9,13,14,15].

The main results that are described in this contribution show the use of educational technology, the perceived usefulness of educational applications, and the use of educational technology as support for students with specific learning difficulties by future professionals of the education.

2.2. Specific Learning Difficulties

A “Specific Learning Difficulty” (SLD) is considered to be the affectation and involvement of language, reading, writing, and/or calculation at a cognitive level.

Within European legislation, there is no unanimous legislative development with regard to learning difficulties. The European Education Area aims to promote cooperation between the Member States of the European Union to further enrich the quality and inclusiveness of national education and training systems in terms of Children’s Rights and the European Child Guarantee [16]. However, each country in the European Union is responsible for its own education and training systems.

One of the objectives of the 2030 agenda is the guarantee of an inclusive education, the quality of which is not a difficulty, and the promotion of learning opportunities, to be developed through particular and general actions.

In Spanish legislation, some interesting aspects have been developed around learning difficulties. With regard to the Spanish legislation, Organic Law 8/2013, of 9 December, for the improvement of educational quality (LOMCE), develops, in its Article 71, these aspects [17]:

- The responsibility for obtaining the means of any kind (human or material) that are considered necessary for the optimal development of students in their intellectual, personal or social levels and for the achievement of the objectives promoted by this law, falls on the educational Administration, likewise these bodies will develop priority intervention plans for centers that school students with special educational needs;

- The resources of students whose special educational needs and specific learning difficulties give rise to extraordinary measures must be ensured and guaranteed.

On the other hand, Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which modifies Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May (LOMLOE), highlights the need for the individualisation of education in the field of inclusive education, with the aim of achieving adequate development within the personal, intellectual, social, and emotional spheres of students [18]. The same legislation considers adaptations to the postcompulsory school stages to be fundamental.

In recent years, educational strategies and methodologies have been developed with an important and necessary vision of inclusion. The most important of these is the Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which was developed by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). The UDL approach focuses on the design of the school curriculum to explain why some students do not reach the expected learning outcomes. CAST criticises that many curricula are designed to cater to “most” students, but not to all.

There are three main principles of the UDL:

- To provide a wide variety of media to encourage student participation and the consequent motivation to learn;

- To carry out the representation of the contents through multiple forms that facilitate the perception and understanding of what is presented. The learner will be able to identify what is most important;

- To let the learners choose the means by which they will express what they have learnt or identify what is most convenient for them. In this way, written tests, oral presentations, or group work can be chosen.

“The curriculum that is created following the UDL framework is designed, from the outset, to meet the needs of all learners, making subsequent changes and the cost and time associated with them unnecessary. The UDL framework encourages the creation of flexible designs from the outset, featuring customizable options that allow all learners to progress from where they are, not where we imagine them to be” [19].

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) brings together didactic practice and neuroscientific research to create flexible curricula that are responsive to all learners.

By following the UDL-curriculum-creation structure that is proposed by [19], multiple forms of presentation and representation of content can be used to optimize learning:

- Options to modify and personalize the presentation of information (offering visual, auditory, motor alternatives…);

- The provision of multiple options for language and symbols (clarifying syntax, vocabulary, mathematical symbols, etc.) and illustrating meaning;

- The provision of options for comprehension (activating prior knowledge and ideas, and aiding information processing and memory).

Active methodologies and the inclusion of technology respond to the UDL approach as they favour the input of information through different senses, cooperative learning, or gamification, and they help to integrate information in a natural and interactive way. The importance of the UDL methodology lies in the process of the positive interdependence of responsibility and interaction. Student interaction fosters peer learning and is based on one of the main characteristics of humans as social beings [20].

The technological approach complements the attention to diversity that is provided by active methodologies by supplying flexible and adaptable environments that facilitate and provide a unitary curriculum for the different students in the classroom.

2.3. Educational Technology and UDL

Research has gone beyond audiovisual technology and has focused on different applications, the objective of which has been the development of reading and writing intervention proposals for students with learning difficulties [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Learning difficulties have been little taken into account within the educational system; however, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in offering quality inclusive education. Educational applications that enable educational intervention for students with specific learning difficulties improve the quality of education and allow for greater inclusion.

The acronym App comes from the term “Application”. In the educational field, we understand “educational Apps” as programmes or multimedia educational resources that are used through mobile devices connected to the Internet.

The use of Apps in education offers some advantages, as long as they are adapted to the needs of the child:

- Learning is extrapolated to any context, and is not specifically circumscribed to the classroom;

- The motivation and involvement of the student is better when using educational Apps sporadically;

- Educational Apps usually have an important playful component, as they integrate the typical dynamics of games and rewards to achieve learning objectives on the basis of gamification. This allows the student to learn while playing;

- They allow for the movement from passive learning to richer and more effective activity-based learning that is focused on active participation throughout the process. As a result, attentional levels are also improved;

- Autonomy and the personalisation of learning are the pillars on which this educational technology is developed;

- Some of these applications favour collaborative environments and, given the current pandemic situation, these environments can be a specific alternative to face-to-face cooperative learning;

- Experience, without the need for uncorrectable errors, is the proposal that is made by many of these applications, which is why it is important training for many skills.

- The versatility of the technological applications, the great variety, and the supply they offer make them adaptable to different contexts and capacities [28,29,30,31].

2.3.1. Educational Apps for Intervention in SLD

Below, some of the educational applications that can be used as an adaptive curricular vehicle for intervention with students with specific learning difficulties will be shown.

2.3.2. Proloquo2Go

This application focuses on augmentative and alternative communication, and it is an ingenious tool for any speech difficulties; in different steps, you can personalise language, voice type, and the access to panels. It uses essential vocabulary at the first level, and it can be accessed at different levels of difficulty. It is based on research by language experts [32].

2.3.3. SnapTypePro

This application translates voice messages into text, and so it is very useful for children with dysgraphia or with any disability or difficulty that may interfere with written language. It also overlays text boxes and allows them to write over them, and so they do not have to copy the questions [33].

2.3.4. MyTalkToolsMobile

This application has boards with different pictograms that can be used to create sentences or communicative sequences [34].

2.3.5. Voice Dream Reader

Voice Dream Reader is an efficient reader that allows you to highlight texts [35].

2.3.6. Co:Writer

This is a Chrome extension that helps with practise and writing correctly by using a wide range of vocabulary and correct grammar [36].

2.3.7. ClaroSoftware

Claro Software combines the features of an efficient reader with multiple tones and voice features, with a spelling and grammar checker and proofreader [37].

3. Materials and Methods

This paper focuses on the field of specific learning difficulties (SLD). Educational technology can provide support and help for pupils whose difficulties can lead to school failure. Teachers and future teachers need to be aware of the technological aids that are available and provided to them in the school environment [38].

This is quantitative research with a descriptive character, the methodology of which allows for the determination of the vision of the participating sample with regard to the subject.

3.1. Objective

The objective of this research is to know the knowledge of future education professionals with regard to the use of educational technology for students with specific learning difficulties.

This objective will contribute to the professional development of future professionals who will work with students with special educational needs.

3.2. Sample

The study population that participated in this research is made up of students from different teaching degrees at the Faculty of Education of the University of Burgos.

In total, the sample of this research is made up of 130 people, of which women predominate (79%), as opposed to men (21%).

All the participants are students in the final years of the teaching degree (3rd and 4th years), with 90 students in the Primary Education Teaching Degree, and 40 students in the Early Childhood Education Teaching Degree.

3.3. Instruments

A 25-item instrument was designed and administered online, which allowed for its distribution and data collection. The instrument has an estimated administration time of 10 min, and it consists of three blocks:

- Educational technology use (13 items). Dichotomous questions (yes/no) are asked to find out whether future educational professionals value the use of technology as an educational resource;

- Perceived usefulness of educational applications (6 items). This block is made up of a series of statements in relation to the perceived usefulness of educational applications according to future teachers. Participants must show their degree of agreement with these statements on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4 (1 being slightly agree, and 4 being strongly agree);

- Educational technology as a support for students with SLD (6 items). This block is made up of a series of statements that relate to educational intervention for students with specific learning difficulties. As in the previous block, the degree of agreement with these statements is assessed on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4.

3.4. Procedure

Initially, the data-collection instrument that was necessary to respond to the research objective was designed. Prior to the administration of the instrument, participants were informed of the voluntary character of the participation, as well as of its anonymity, and that all of the information included in the document would be treated confidentially and for the sole purpose of research, in accordance with the current legislation in Spain (Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Personal Data Protection and the guarantee of digital rights). To this end, informed consent was obtained from the participants.

The statistical-data-analysis process was carried out with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 21 for Windows, licensed by the University of Burgos, Burgos, Spain).

4. Results

This section shows a descriptive analysis of the results in relation to the blocks that make up the questionnaire that was administered. The first section details the questions related to the use of educational technology by future educational professionals. The second one shows the perceived usefulness of educational applications, and, finally, the third one displays the evaluation of the use of educational technology as a support for students with specific learning difficulties. As explained above, the participating sample is made up of 130 students from the Faculty of Education of the University of Burgos, with 69% of them from the degree in Primary Education, and 31% from the degree in Early Childhood Education.

4.1. Use of Educational Technology

Table 1 below shows the purely descriptive data from the first block of the questionnaire. In general, it is observed that:

Table 1.

Use of Educational Technology.

- In their totality, the students participating in the research indicate having knowledge in the use of educational platforms, mobile devices, as well as social networks. They also state that they will introduce educational applications to adapt the contents to the educational needs of the students in their professional futures;

- Almost three-quarters are familiar with tools for building websites and/or blogs (73.07%);

- Very few have used specific software to support their teaching–learning process (9.23%);

- In relation to the use of social networks, Instagram is the predominant one (92.30%), followed by Twitter (55.38%), and Facebook (33.07%);

- A total of 7 out of 10 have used educational applications;

- The percentage of students who know the principles on which the Universal Design for Learning is based is very low (26.15%);

- A total of 9 out of 10 consider that educational technology can favour intervention in students with specific learning difficulties;

- Practically all of them consider that training in the use of educational technology is necessary for teaching (98.46%).

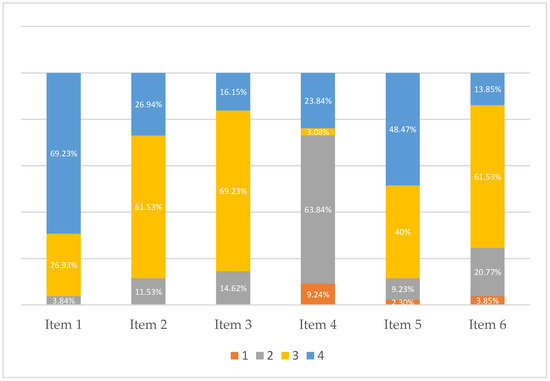

4.2. Perceived Usefulness of Educational Applications

In relation to the perceived usefulness of educational applications, Table 2 shows the results that were obtained in relation to the degree of agreement with the statements (1 being slightly agree, and 4 being strongly agree) included in the questionnaire, which highlight the following results:

Table 2.

Perceived usefulness of educational applications.

- A total of 7 out of 10 strongly agree that educational applications enable learning in any educational context;

- In relation to the influence of the use of educational applications, 61.53% consider that they have a positive influence on pupils’ motivation;

- A total of 85.38% of the respondents agree that there is a high degree of agreement on the relationship between the recreational component of most educational Apps and student learning;

- With regard to the promotion of students’ active participation and their interaction with the rest, the degree of agreement is low with respect to the rest of the items;

- Almost 90% of the participants consider that the use of educational applications makes it possible to create a more personalised learning environment that is adapted to the specific needs of each student and that contributes to fostering autonomous learning;

- Three-quarters are in favour of the creation of teamwork spaces in collaborative environments.

For a better visualization of the results in relation to the perceived usefulness of educational applications, a bar graph is provided in which the percentages that were obtained for each evaluated item are shown (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graph of perceived usefulness of educational applications.

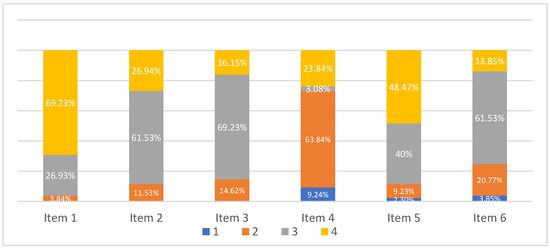

4.3. Educational Technology as Support for Students with SLD

Finally, the third section of the questionnaire focuses on educational technology as a support for students with SLD. The results that were obtained in this respect are presented in Table 3, and they highlight that:

Table 3.

Educational Technology as support for students with SLD.

- Few students consider that educational technology contributes to the diagnosis of students with SLD (26.92%);

- A total of 8 out of 10 believe that it favours the autonomy of students, as the tools can be adapted to the needs of each student in a personalised way, and that it can help to overcome the limitations that are derived from these difficulties;

- A total of 75% strongly agree that the use of educational technology can equalise the abilities of students in relation to the same content;

- Almost 90% consider that educational technology is a simple and inexpensive resource to bring to the classroom;

- Virtually all participants state that the use of educational technology increases students’ motivation to learn (98.46%).

For a better visualization of the results in relation to educational technology as support for students with SLD, a bar graph is provided that shows the percentages obtained for each item evaluated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graph of Educational Technology as support for students with SLD.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to find out the vision of future educational professionals who are the future teachers of primary education and early childhood education with regard to the use of educational technology for pupils with specific learning difficulties.

The results obtained show that the sample is quite knowledgeable about the use of educational technology, as they are used to using educational platforms, mobile devices, social networks, educational applications, blogs, websites, etc. However, very few have used specific software to support their learning. The limited number of participants who have knowledge of the principles on which the Universal Design for Learning is based is also noteworthy. It should be noted that they are aware of the importance of educational technology in the intervention with students with specific learning difficulties; therefore, almost all of them consider that training in the use of educational technology is necessary for teaching.

The different emerging technologies within the field of education are revolutionising the vision of learning difficulties. Augmented Reality (AR), the Semantic Web, and Virtual Reality (VR) are resources that, with proper knowledge of them, can be key in the development of school curricula [9].

On the other hand, the analysis related to the perceived usefulness of the use of educational applications shows very positive results, as future education professionals show high levels of agreement in relation to the didactic possibilities that are offered by these technological resources in terms of learning, motivation, active participation, autonomous learning, and even the possibility of teamwork.

Previous research has shown that the motivation a priori that is provoked by the use of technology stimulates and reinforces students in their learning through the combination of school content with playful environments, which contributes to the acquisition of knowledge becoming the focus of the child’s interest [39].

Finally, if we focus on educational technology as a support for students with specific learning difficulties, the results are less positive, as few consider that educational technology can contribute to the overcoming of these difficulties. Perhaps these results are due to the lack of training in the subject, which sheds light on the need for training and professional pedagogical updating, and the need to include different applications and programmes in university classrooms so that future teachers can learn about their potential. Despite this result, high levels of agreement are obtained in relation to the use of technological resources as a tool to help meet the needs of students.

Educational technology turns learning into games, and it gamifies learning, helps and empowers those with specific learning difficulties to work on the difficulties they present, and also generates a personalised pedagogical environment [22]. However, there is still little research on intervention through technology [23].

Some applications that were developed to work on dyslexia use this technology; Luz Rello’s Dytective program analyses more than two hundred possible variables in student responses through AI [40].

Another emerging project that uses AI is VRAllexia, which is an Erasmus project, through which a platform with materials for university students with dyslexia is being developed. The platform takes as the input clinical-dyslexia-diagnostic reports, the responses to a self-assessment questionnaire, and the results of a battery of psychometric tests to extract useful information about the problems and needs of dyslexic students at university. By relying on AI, it will be able to automatically predict which of the support methodologies is the most appropriate for each student, both in terms of best practices to be followed by teachers and institutions, as well as digital tools to make learning more accessible. [41].

Virtual Reality is another of the pillars within educational innovation with learning difficulties. Specifically, Virtual Reality (VR) is an evaluation and intervention tool in the school environment [42]. This technology allows the generation of dynamic and controllable 3D environments, stimulus control, and the documentation and quantification of behaviour, which are characteristics that make it unique [43].

Nevertheless, not a lot research has yet been conducted regarding its use for educational intervention [44].

The results of the analysis of the research by Eman Al-Zboon and Kholoud Adeeb Al-Dababneh (2021) show that there is a correlation between the skills of teachers and the availability of technological resources, and these results are repeated in the teaching of children with learning difficulties. However, other current research has found that teachers reported low levels of knowledge, skills, and confidence in technology. Many described limited access to training and support for the use of educational technology. The results also reveal nonsystemic thinking [45,46].

Therefore, we consider that the results that are shown in this research represent a first approach to the subject under study, and we are aware of the need to expand the knowledge about different tools that can respond to learning difficulties, and that can thus achieve inclusive education for all.

It is essential to know the starting point of the knowledge of future teachers in order to be able to influence their learning.

In future research, the study will be carried out by taking into account different university approaches and a larger sample in order to find more generalizable results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.R.-C., V.D.-B., J.L.C.-G. and R.d.l.F.-A.; methodology: S.R.-C.; software: V.D.-B.; formal analysis: V.D.-B.; investigation: S.R.-C. and V.D.-B.; resources: J.L.C.-G. and R.d.l.F.-A.; data curation: S.R.-C. and V.D.-B.; writing—original draft preparation: V.D.-B.; writing—review and editing: S.R.-C.; visualization: J.L.C.-G. and R.d.l.F.-A.; supervision: S.R.-C. and V.D.-B.; project administration: J.L.C.-G.; funding acquisition: the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been co-financed by Project Indigo! of the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain), with reference number PID2019-105951RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all students involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the collaboration of the research participants, as well as the persons who collaborate in the Project Indigo!

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sevillano, M.; Rodríguez, R. Integración de tecnologías de la información y comunicación en educación infantil en Navarra. Píxel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2013, 42, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Directrices sobre Políticas de Inclusión en la Educación. Organización de las Naciones Unidaspara la Educación, la Ciencia et la Cultura. 2009. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001778/177849s.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Benitez Jaén, A.; Peral Ortega, R.; Hermida Fernández, J.M. El aprendizaje de nuevas tecnologías para la vida autónoma. In Inclusive University. Experiences with People with Cognitive Functional Diversity; Díaz Jiménez, R.M., Ed.; Pyramid Editions: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, W.; Vera, Y.; Méndez, E. TIC: ¿Para qué? Funciones de las tecnologías de la información. Rev. Científica Mundo Investig. Conoc. 2018, 2, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.R.; González, M.J.A. Las TIC al servicio de la inclusión educativa. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2015, 25, 108–126. [Google Scholar]

- Thelijjagoda, S.; Chandrasiri, M.; Hewathudalla, D.; Ranasinghe, P.; Wickramanayake, I. The Hope: An Interactive Mobile Solution to Overcome the Writing, Reading and Speaking Weaknesses of Dyslexia. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–21 August 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 808–813. [Google Scholar]

- Ndombo, D.M.; Ojo, S.; Osunmakinde, I.O. An intelligent integrative assistive system for dyslexic learners. J. Assist. Technol. 2013, 7, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.; Zorzi, M.; Ziegler, J.C. Understanding dyslexia through personalized large-scale computational models. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cano, S.R.; Delgado-Benito, V.; Gonçalves, V. Educational Technology Based on Virtual and Augmented Reality for Students With Learning Disabilities: Specific Projects and Applications. In Emerging Advancements for Virtual and Augmented Reality in Healthcare; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Córdoba-Pérez, M.; Fernández Batanero, J.M. Las TIC Para la Igualdad; Eduforma: Seville, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero, J. (Ed.) Nuevas Tecnologías Aplicadas a la Educación; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, C.; Toledo, P. Las tecnologías como apoyo a la diversidad del alumnado. In Tecnología Educativa; Cabero Almenara, J., Ed.; Mc Graw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Eynon, R. Historical threads, missing links, and future directions in AI in education. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef AM, F.; Atia, A.; Youssef, A.; Eldien NA, S.; Hamdy, A.; Abd El-Haleem, A.M.; Elmesalawy, M.M. Automatic Identification of Student’s Cognitive Style from Online Laboratory Experimentation using Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the2021 IEEE 12th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 1–4 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 0143–0149. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, F.; Holmes, W.; Huang, R.; Zhang, H. AI and Education: A Guidance for Policymakers; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies. Eurydice Report. RINED, Revista de Recursos para la Educación Inclusiva. 2021; Volume 1, p. 1. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/36bde79d-6351-489a-9986-d019efb2e72 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la mejora de la calidad educativa. Boletín Of. Estado 2013, 295, 97858–97921. Available online: http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2013/12/10/pdfs/BOE-A-2013-12886.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación (LOMLOE). Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- CAST (Center for Applied Special Technology). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.0; CAST: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- González, R.M.G.; González, L.G.; de la Cruz, N.M.; Fuentes, M.G.L.; Aguirre, E.I.R.; González, E.V. Acercamiento epistemológico a la teoría del aprendizaje colaborativo. Apertura 2012, 4, 156–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cidrim, L.; Braga, P.; Madeiro, F. Desembaralhando: A Mobile Application for Intervention in the Problem of Dyslexic Children Mirror Writing. Rev. CEFAC 2018, 20, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidrim, L.; Madeiro, F. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) applied to dyslexia: Literature review. Rev. CEFAC 2017, 19, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalyvioti, K.; Mikropoulos, T.A. A virtual reality test for the identification of memory strengths of dyslexic students in Higher Education. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2013, 19, 2698–2721. [Google Scholar]

- Saputra, M.R.U.; Alfarozi, S.A.I.; Nugroho, K.A. LexiPal: Kinect-based application for dyslexia using multisensory approach and natural user interface. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2018, 57, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Skiada, R.; Soroniati, E.; Gardeli, A.; Zissis, D. EasyLexia: A mobile application for children with learning difficulties. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 27, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suárez, A.I.; Pérez, C.Y.; Vergara, M.M.; Alférez, V.H. Desarrollo de la lectoescritura mediante TIC y recursos educativos abiertos. Apertura 2015, 7, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Jamali, H.R.; Nicholas, D. Using ICT with people with special education needs: What the literature tells us. Aslib Proc. 2006, 58, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikl, P.; Bartošová, I.K.; Víšková, K.J.; Havlíčková, K.; Kučírková, A.; Navrátilová, J.; Zetková, B. The possibilities of ICT use for compensation of difficulties with reading in pupils with dyslexia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 176, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mura, G.; Carta, M.G.; Sancassiani, F.; Machado, S.; Prosperini, L. Active exergames to improve cognitive functioning in neurological disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 54, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Tech Evocate. Available online: https://www.thetechedvocate.org/7-must-app-andtools-students-learning-disabilities/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Edwards, J.; Waite-Jones, J.; Schwarz, T.; Swallow, V. Digital Technologies for Children and Parents Sharing Self-Management in Childhood Chronic or Long-Term Conditions: A Scoping Review. Children 2021, 8, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proloquo2Go. AAC App with Symbols—AssistiveWare. Available online: https://www.assistiveware.com/products/proloquo2go (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- SnapType. A Simple Way to Complete any School Worksheet on Your iPad or Tablet. Available online: http://www.snaptypeapp.com/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- MyTalkTools Mobile. Mytalktools Mobile AAC. Available online: https://www.mytalktools.com/dnn/Products.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Voice Dream Reade. Voice Dream—Accessible Reading Tool. Available online: https://www.voicedream.com/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Co:Writer. Kickstarts the Writer Inside with Word Prediction, Translation, and Speech Recognition. Available online: https://learingtools.donjohnston.com/product/cowriter/ (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Claro Software. Claro Software Assistive Technology. Available online: https://www.clarosoftware.com/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Cano Rodríguez, S.; Alonso Sebastián, P.; Delgado Benito, V.; Ausín Villaverde, V. Evaluation of Motivational Learning Strategies for Children with Dyslexia: A FORDYSVAR Proposal for Education and Sustainable Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education. Planning Education in the AI Era: Lead the Leap: Final Report; UNESCO: Beijing, China, 2019; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370967 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Rello, L.; Ballesteros, M.; Ali, A.; Serra, M.; Alarcón, D.; Bigham, J.P. Dytective: Diagnosing risk of dyslexia with a game. In Proceedings of the Pervasive Health’16, Cancun, Mexico, 16–19 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zingoni, A.; Taborri, J.; Panetti, V.; Bonechi, S.; Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Pinzi, S.; Calabrò, G. Investigando Problemas y Necesidades de Estudiantes Disléxicos en la Universidad: Prueba de Concepto de una Plataforma de Apoyo Basada en Inteligencia Artificial y Realidad Virtual y Resultados Preliminares. Apl. Cienc. 2021, 11, 4624. [Google Scholar]

- Aznar Díaz, I.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.M.; Rodríguez-García, A.M. La tecnología móvil de Realidad Virtual en educación: Una revisión del estado de la literatura científica en España. EDMETIC Rev. Educ. Mediática TIC 2018, 7, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizzo, A.; Difede, J.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Daughtry, J.M.; Reger, G. Virtual Reality as a Tool for Delivering PTSD Exposure Therapy In Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Future Directions in Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment; Safir, M., Wallach, H., Rizzo, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 760–866. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, M.; Zad, D.; MacKinnon, L.; Bacon, L. A multisensory 3D environment as intervention to aid reading in dyslexia: A proposed framework. In Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Würzburg, Germany, 5–7 September 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Siobhan Long, A.M.G.; Malcolm Maclachlan, K.M. Using a systems thinking approach to understand teachers perceptions and use of assistive technology in the republic of Ireland. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zboon, E.; Adeeb Al-Dababneh, K. Using assistive technology in a curriculum for preschool children with developmental disabilities in Jordan. Education 3-13 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).