The Practice of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries on the High Seas: Challenges and Suggestions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries

3. The Practice of EAF in High Seas Fishery Management

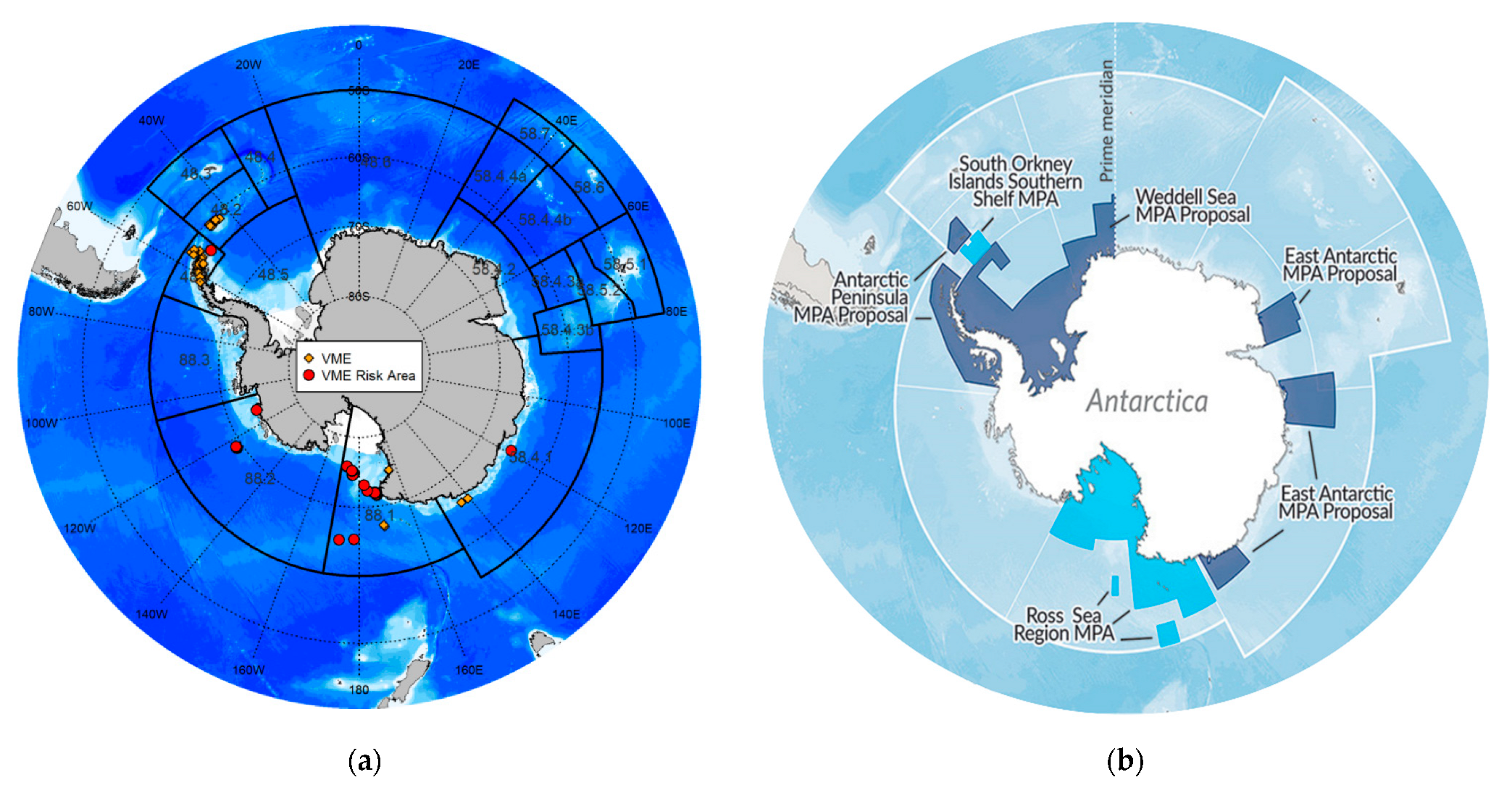

3.1. CCAMLR Plays a Leading Role in EAF Practicing

3.2. The Practice of EAF by Other RFMOs

4. Challenges with Practicing the EAF in High Seas Fishery Management

4.1. Constraints by the Approach Itself

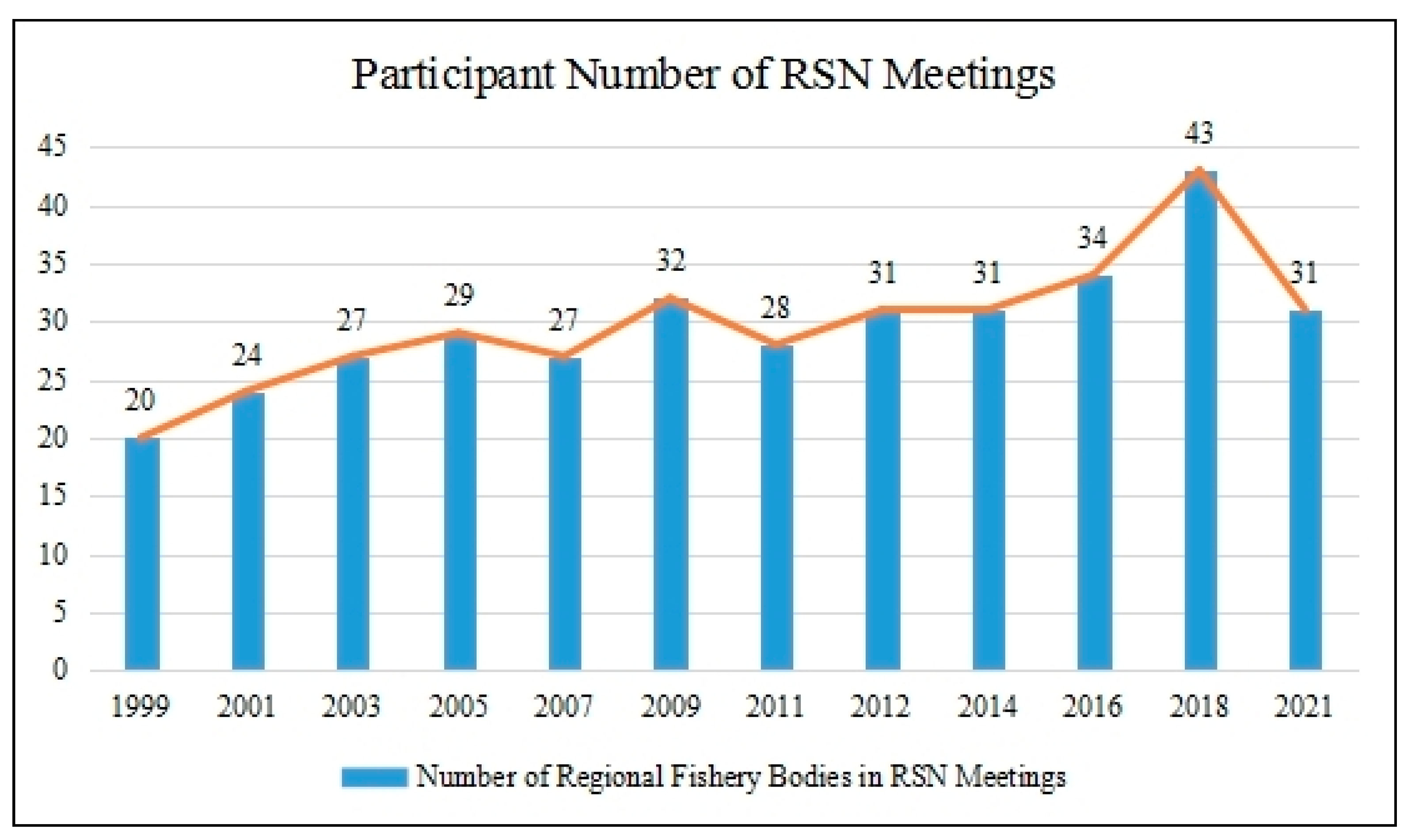

4.2. Increasing Stakeholders Affect the Implementation of the EAF

4.3. Inconsistent with Political Ocean Boundaries

4.4. Resistance from Vested Interests

4.5. The Effect of the EAF Is Threatened by IUU Fishing

5. Ideas to Meet Challenges

5.1. Building a Sense of Maritime Community with Shared Future

5.2. Advancing the Approach by Explicating Definition, Objectives, and Priorities

5.3. Strengthening Coordination and Cooperation between States and RFMOs

5.4. Adopting Biogeographical Criteria-Based ABMTs

5.5. Enhancing the Level of Stakeholders’ Participation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Worm, B.; Barbier, E.B.; Beaumont, N.; Duffy, J.E.; Folke, C.; Halpern, B.S.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Lotze, H.K.; Micheli, F.; Palumbi, S.R.; et al. Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services. Science 2006, 314, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 86. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Spiteri, C.; Senechal, T.; Hazin, C.; Hampton, S.; Greyling, L.; Boteler, B. Study on the Socio-Economic Importance of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in the Southeast Atlantic Region. STRONG High Seas Project 2021, 27. Available online: https://www.prog-ocean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Africa-Socio-Economic-Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Pikitch, E.K.; Santora, C.; Babcock, E.A.; Bakun, A.; Bonfil, R.; Conover, D.O.; Dayton, P.; Doukakis, P.; Fluharty, D.; Heneman, B.; et al. Ecosystem-Based Fishery Management. Science 2004, 305, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, J. What is the Ecosystem Approach for Fisheries Management. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouwborst, A. The Precautionary Principle and the Ecosystem Approach in International Law: Differences, Similarities and Linkages. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 2009, 18, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Cochrane, K. Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: A Review of Implementation Guidelines. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2005, 62, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cowan, J.H.; Rice, J.C.; Walters, C.J.; Hilborn, R.; Essington, T.E.; Day, J.W.; Boswell, K.M. Challenges for Implementing an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2012, 4, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Techera, E.; Al Arif, A. Ecosystem-based fisheries management and the precautionary approach in the Indian Ocean regional fisheries management organisations. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayfuse, R. Climate Change and Antarctic Fisheries: Ecosystem Management in CCAMLR. Ecol. Law Q. 2018, 45, 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, R.D.; Trathan, P.N.; Hill, S.L.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Meredith, M.P.; Hollyman, P.; Krafft, B.A.; MC Muelbert, M.; Murphy, E.J.; Sommerkorn, M.; et al. Utilising IPCC Assessments to Support the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management within a Warming Southern Ocean. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trathan, P.N.; Fielding, S.; Hollyman, P.R.; Murphy, E.J.; Warwick-Evans, V.; Collins, M.A. Enhancing the ecosystem approach for the fishery for Antarctic krill within the complex, variable, and changing ecosystem at South Georgia. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 78, 2065–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNGA Resolution. Report on the Work of the United Nations Open-Ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea at Its Seventh Meeting. UN Doc. A/61/156, p. 2. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/432/90/pdf/N0643290.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- FAO. FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries 4, Suppl. 4, Add. 2. 2009, pp. 6–7. Available online: https://www.fao.org/docrep/pdf/011/i0151e/i0151e00.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- CBD COP 9 Decision IX/7. Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at Its Ninth Meeting. 2008. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-09/cop-09-dec-07-en.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Report of the Resumed Review Conference on the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks. UN Doc. A/CONF.210/2016/5. 2016, p. 35. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N16/244/06/pdf/N1624406.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Ntona, M.; Morgera, E. Connecting SDG 14 with the Other Sustainable Development Goals through Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy 2018, 98, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A.J.; Campbell, N.; Koen-Alonso, M.; Pepin, P.; Diz, D. Delivering sustainable fisheries through adoption of a risk-based framework as part of an ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suietnov, Y. Formation and Development of the Ecosystem Approach in International Environmental Law before the Convention on Biological Diversity. J. Environ. Law Policy 2021, 47, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. Article 2(3)(b). Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention-text (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- CCAMLR. Krill Fisheries and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/fisheries/krill-fisheries-and-sustainability (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- CCAMLR. Ecosystem Monitoring Program. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/science/ccamlr-ecosystem-monitoring-program-cemp (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- CCAMLR. Browse Conservation Measures. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/conservation-and-management/browse-conservation-measures (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 21-01. 2019. Available online: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/21-01_23.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 21-02. 2019. Available online: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-21-02-2019 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 22-06. 2019. Available online: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/22-06.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-03. 2009. Available online: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/91-03_9.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-05. 2016. Available online: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/91-05_11.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in Northeast Atlantic Fisheries. Articles 4(2)(c), 4(2)(d). Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ad378391-35b0-40fc-959b-cc84e1d17701/language-en (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Amendment to the Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries. 2007. Available online: https://leap.unep.org/sites/default/files/treaty/TRE160039.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Convention on the Conservation and Management of Fishery Resources in the South East Atlantic Ocean. Articles 3(c), (d), (e), (f). Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/legal/docs/032s-e.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. Article 5. Available online: https://www.wcpfc.int/system/files/text.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Submission by the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission: Regarding the report of the Secretary-General of the United Nations on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, Pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 75/239. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/general_assembly/contributions_2021/NEAFC.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Recommendation 10 (2021) to amend Recommendation 19 (2014) on the Protection of Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems in the NEAFC Regulatory Area. 2021. Available online: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/mul201787.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Pinto, D.D.P. Fisheries Management in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction: The Impact of Ecosystem Based Law-Making; Martinus Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Memorandum of Understanding between the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) and the OSPAR Commission. Available online: https://www.ospar.org/documents?d=32804 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Key Figures of the MPA OSPAR Network. Available online: https://mpa.ospar.org/home-ospar/key-figures (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Convention on Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries. Articles VI(6)(c), VI (7). Available online: https://www.nafo.int/Portals/0/PDFs/key-publications/NAFOConvention.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Koen-Alonso, M.; Pepin, P.; Fogarty, M.J.; Kenny, A.; Kenchington, E. The Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Roadmap for the development and implementation of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: Structure, State of Development, and Challenges. Mar. Policy 2019, 100, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization. Report of the NAFO Scientific Council Working Group on Ecosystem Approaches to Fisheries Management. 2010, pp. 75–81. Available online: https://archive.nafo.int/open/sc/2010/scs10-19.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization. Scientific Council Reports 2019. Available online: https://www.nafo.int/Portals/0/PDFs/rb/2019/Redbook2019v2.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- NAFO Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VME) Closures. Available online: https://www.nafo.int/Fisheries/VME (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- SEAFO Report. Implementation of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/ICSP15/SEAFO-ICSP15Contribution.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- SEAFO Management. Available online: http://www.seafo.org/Management (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- WCPFC Secretariat. Implementation of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/ICSP15/WCPFC-ICSP15Contribution.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Kirkfeldt, T.S. An Ocean of Concepts: Why Choosing between Ecosystem-based Management, Ecosystem-based Approach and Ecosystem Approach Makes a Difference. Mar. Policy 2019, 106, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Secretary-General. Sustainable Fisheries, Including through the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, and Related Instruments. UN Doc. A/59/298, 2004. pp. 22–26. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N04/471/20/pdf/N0447120.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Link, J.S.; Huse, G.; Gaichas, S.; Marshak, A.R. Changing How We Approach Fisheries: A First Attempt at an Operational Framework for Ecosystem Approaches to Fisheries Management. Fish Fish. 2020, 21, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlet, D.; Rayfuse, R. The Ecosystem Approach in Ocean Planning and Governance: Perspectives from Europe and Beyond; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Bone, J.; Clavelle, T.; Ferreira, J.; Grant, J.; Landner, I.; Immink, A.; Stoner, J.; Taylor, N. Best Practices for Aquaculture Management: Guidance for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach in Indonesia and Beyond. 2018, p. 14. Available online: https://sustainablefish.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Aquaculture-Best-Practices-Guide-Nov-9-web-1.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Garcia, S.M.; Rice, J. Anthony Charles. Governance of Marine Fisheries and Biodiversity Conservation: Interaction and Coevolution; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.A.; Fulton, E.A.; Haward, M.; Johnson, C. Consensus Management in Antarctica’s High Seas: Past Success and Current Challenges. Mar. Policy 2016, 73, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDorman, T. Implementing Existing Tools: Turning Words into Actions—Decision-Making Processes of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2005, 20, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, S.V.R.K.; Scheyvens, H.; Takahashi, Y. Ecosystem-Based Approaches in G20 Countries: Current Status and Priority Actions for Scaling Up. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, 2019; pp. 9–10. Available online: https://www.iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/discussionpaper/en/6995/EbA+in+G20_Discussion+paper+Final.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Elayaperumala, V.; Hermesb, R.; Brown, D. An Ecosystem Based Approach to the Assessment and Governance of the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem. Deep Sea Res. Part II 2019, 163, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, P.S.; Essington, T.E.; Marshall, K.N.; Koehn, L.E.; Anderson, L.G.; Bundy, A.; Carothers, C.; Coleman, F.; Gerber, L.R.; Grabowski, J.H.; et al. Building Effective Fishery Ecosystem Plans. Mar. Policy 2018, 96, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Seara, T. Integrating Stakeholders’ Perceptions into Decision-Making for Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management. Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD. Principles of Ecosystem Approach. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/ecosystem/principles.shtml (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- De Lucia, V. Towards Ecosystem-Based Governance of the High Seas. International Institute for Environment and Development. 2020. Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/17757IIED.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Jin, Y. On the Theoretical Regime of the Maritime Community with a Shared Future. J. Ocean. Univ. China 2021, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. A How-to Guide on Legislating for an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries. 2016, p. 54. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5966e.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Waylen, K.A. How does legacy create sticking points for environmental management? Insights from challenges to implementation of the ecosystem approach. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. IUU Vessel List. Available online: https://www.fao.org/gfcm/data/iuu-vessel-list (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Berveridge, M.; Dieckmann, U.; Fock, H.O.; Froese, R.; Keller, M.; Löwenberg, U.; Merino, G.; Möllmann, C.; Pauly, D.; Prein, M.; et al. World Ocean Review 2013; Maribus: Hamburg, Germany, 2013; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Liddick, D. The Dimensions of a Transnational Crime Problem: The Case of IUU Fishing. Trends Organ. Crime 2014, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. How to Banish the Ghosts of Dead Fishing Gear from Our Seas? 2018. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-banish-ghosts-dead-fishing-gear-our-seas (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in Action. 2020, p. 91. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Østhagen, A.; Spijkers, J.; Totland, O.A. Collapse of cooperation? The North-Atlantic Mackerel Dispute and Lessons for International Cooperation on Transboundary. Marit. Stud. 2020, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Chang, Y.C.; Zhang, L.F. An Ocean Community with a Shared Future: Conference Report. Mar. Policy 2020, 116, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenchiang, C. On Legal Implementation Approaches toward a Maritime Community with a Shared Future. China Leg. Sci. 2020, 8, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Regional Fishery Body Secretariats Network. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/rsn (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- FAO Regional Fishery Body Secretariats Network. 20 Years Looking Back: The Journey So Far. 2019, pp. 41–91. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca3925en/CA3925EN.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- FAO. Report of the Meeting of FAO and Non-FAO Regional Fishery Bodies or Arrangements. 1999. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/X1840E/X1840E00.htm (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Thomson, A. The ManaKenneth Shermangement of Redfish (Sebastes Mentella) in the North Atlantic Ocean—A Stock in Movement. FAO. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2004406289 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Constable, A.J. Lessons from CCAMLR on the Implementation of the Ecosystem Approach to Managing Fisheries. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topor, Z.M.; Rasher, D.B.; Duffy, J.E.; Brandl, S.J. Marine protected areas enhance coral reef functioning by promoting fish biodiversity. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, R.B.; Bradley, D.; Mayorga, J.; Goodell, W.; Friedlander, A.M.; Sala, E.; Costello, C.; Gaines, S.D. A global network of marine protected areas for food. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.; Lewis, A.; Gold, B.D. Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation and Sustainability; AAAS Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lambach, D. The Functional Territorialization of the High Seas. Mar. Policy 2021, 130, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, A.R. Ecological Geography of the Sea, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2007; pp. 90–475. [Google Scholar]

- High Seas Marine Protected Area. Marine Protection Atlas. Available online: https://mpatlas.org/countries/HS (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Takei, Y. Filling Regulatory Gaps in High Seas Fisheries: Discrete High Seas Fish Stocks, Deep-Sea Fisheries and Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- Partnerships Involving Stakeholders in the Celtic Sea Ecosystem (PISCES). A Guide to Implementing the Ecosystem Approach through the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. 2012, p. 7. Available online: https://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/the_pisces_guide.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Mackinsona, S.; Middletonb, D.A.J. Evolving the Ecosystem Approach in European Fisheries: Transferable Lessons from New Zealand’s Experience in Strengthening Stakeholder Involvement. Mar. Policy 2018, 90, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.A.; Haward, M. The Human Side of Marine Ecosystem-based Management (EBM): ‘Sectoral Interplay’ as a Challenge to Implementing EBM. Mar. Policy 2019, 101, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Representative Measures |

|---|---|

| 1 | consider the impact on associated or dependent species and ecosystems |

| 2 | strictly control destructive fishing gear |

| 3 | prevent or reduce by-catch |

| 4 | control bottom fishing and protect VMEs |

| 5 | adopt area-based management tools |

| RFMO | Specific Measures |

|---|---|

| NEAFC | control fishing gear strictly to reduce by-catch identify 13 VMEs and prohibit bottom fishing in these areas cold-water coral conservation and management establish 7 MPAs with OSPAR based on biogeographic criteria |

| NAFO | identify bioregion, Ecosystem Production Unit and ecoregion determine the total allowable catch based on ecosystem model identify 20 VMEs and adopt protection measures |

| SEAFO | identify VMEs, set up closed areas and restrict bottom trawling adopt measures to reduce by-catch of seabirds and turtles |

| WCPFC | data collection incorporates economic, social and cultural aspects adopt measures for addressing the impacts of fishing on the ecosystem implement control and surveillance activities |

| Number | Challenges |

|---|---|

| 1 | constraints by the approach itself |

| 2 | increasing stakeholders affect the implementation of the EAF |

| 3 | inconsistent with political ocean boundaries |

| 4 | resistance from vested interests |

| 5 | the effect of the EAF is threatened by IUU Fishing |

| Number | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| 1 | building a sense of maritime community with shared future |

| 2 | advancing the approach by explicating definition, objectives and priorities |

| 3 | strengthening coordination and cooperation between states and RFMOs |

| 4 | adopting biogeographical criteria-based ABMTs |

| 5 | enhancing the level of stakeholders’ participation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Guo, P. The Practice of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries on the High Seas: Challenges and Suggestions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106171

Dong L, Guo P. The Practice of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries on the High Seas: Challenges and Suggestions. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106171

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Limin, and Peiqing Guo. 2022. "The Practice of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries on the High Seas: Challenges and Suggestions" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106171

APA StyleDong, L., & Guo, P. (2022). The Practice of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries on the High Seas: Challenges and Suggestions. Sustainability, 14(10), 6171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106171