1. Introduction

The conceptualization of intangible cultural heritage has passed through several stages that have not only enhanced it with new conceptual contributions but also given it a regulatory body to safeguard it. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established in 2003 a definition of the areas this type of heritage encompasses. These include music and cultural expressions represented in the variety of areas falling under the intangible cultural heritage umbrella. Although the regulatory framework for music is limited, UNESCO listed it as World Cultural Heritage in 1994. Since then, music has acquired a special meaning within intangible cultural heritage due to its representativeness and significance [

1]. Besides defining and outlining the various areas of intangible cultural heritage, regulations highlight, as one of its main features, that it is the source of cultural diversity. Consequently, its importance for developing and safeguarding people’s culture is evident [

1]. In response to the agreements this international organization adopted, the member states established measures to comply with the decisions reached in Paris at the 32nd General Conference of UNESCO. Spain, a member since 1953, has taken major steps in recognizing, safeguarding, and disseminating intangible cultural heritage. As a result, the country ratified the agreements of the 2003 Convention in 2006 and, nine years later, it enacted Act 10/2015, of 26 May, to safeguard intangible cultural heritage, aimed at regulating public authorities’ actions regarding intangible cultural heritage assets.

The importance of culture for human development justifies the need to preserve it. It is deemed to play a key role in development policies, since cultural heritage—specifically intangible cultural heritage—as an essential part of traditional popular culture, is an invaluable resource related to several objectives set out in the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. As Martinell et al. [

2] point out, although the 2030 Agenda does not explicitly include a cultural goal, culture is addressed in a cross-disciplinary fashion in several of the outlined targets. For that reason, goals such as quality education, sustainable cities, and economic growth, among others, make it possible to emphasize culture as an expression and intrinsic part of people’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

Although there is no sustainable development goal (SDG) for culture in the 2030 Agenda, the targets established for compliance include criteria that generally attach significance to valuing cultural diversity. Point 36, for instance, refers to the need to foster recognition of cultural and natural identity. Similarly, they recognize the contribution culture makes to sustainable development [

2]. In the targets put forward to comply with SDG 11 Sustainable cities and communities, the Danish Institute for Sustainable Development (DISUD) highlights the importance of protecting and safeguarding natural cultural heritage [

3] as a necessary resource for development. At the same time, education-related goals also involve culture as a key factor in the process of economic and social growth. In this regard, 4.7 focuses on the requirement for all learners to acquire the knowledge they need to appreciate cultural diversity. Similarly, target 11.4 mentions the need to protect and safeguard cultural heritage, and education plays a crucial role in this goal [

4].

The leap forward in the concept of development in recent decades is essential to understanding the development process involving both cultural heritage and sustainability [

5]. An in-depth analysis of the concept has increased its scope of action as it is not considered a process dependent merely on economic concerns—the cultural dimension is also an intrinsic part of development policies. Therefore, it is plausible to deduce that culture is vital for progress and cultural heritage has an impact on and contributes to economic and social growth processes. As a finite resource, cultural heritage helps meet long-term requirements such as identity and the feeling of belonging [

6]. Similarly, social interest in intangible cultural heritage has increased considerably, especially due to the economic potential it brings [

7].

Cultural heritage leads to a varied range of economic flows. These are more than enough reasons to justify the efforts and resources earmarked to preserve them. Valuing heritage encourages social integration and the establishment of small heritage-based companies. Traditions, music, artisanal techniques, and know-how influence the cultural and economic development of a territory [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The above criteria highlight the importance of the sustainability of cultural legacy. To ensure human sustainability and development, culture needs to be assimilated holistically and as the foundation of human processes [

12].

Based on the importance and significance cultural heritage has acquired in recent years [

13], several researchers have explored the subject from a variety of perspectives, delving into heritage education and, specifically, the identity-related link established with heritage [

14,

15,

16]. Concerning education, Cuenca [

17,

18] and Jiménez et al. [

19] have explored teaching, good practices in heritage education, its educational value, and links between emotions, territory, and citizenship. González-Monfort [

20] reflected on the educational value of heritage in training a critical citizenry. Educommunication, heritage education, and the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) are subjects other authors have studied [

21,

22,

23]. Bortolotto (2014) [

7] analyzed problems concerning intangible cultural heritage. Villasenor and Zolla [

24] explored the heritagization process. Carrera [

25], meanwhile, approached it through anthropology as a way to safeguard it, and Inga-Aguagallo [

26] and González and López [

27] used the economic perspective to explore how important it is for developing tourism.

Education is a key factor in achieving the SDGs, and heritage education in the different contexts and educational stages is essential for attaining them. Researchers and teachers have made significant contributions to the matter. Fontal [

13], for example, pointed out that heritage education should become a goal in the educational process of formal education since, among other reasons, its aim is to develop ethical, civic, and affective values that are essential for safeguarding cultural heritage. Consequently, communicating and spreading awareness of heritage is vital in order to appreciate and protect it [

28,

29,

30]. We cannot appreciate what we do not know, and, in this regard, education is the foundation for the process. Castro et al. [

31] agree with this stance by stating that identifying with heritage is crucial for its valuing and that studying it can help encourage significant social learning. This author recognizes the importance of heritage education from an early age. Education based on and striving for heritage should not be understood as a mere insight into the past, since the present and future are not only inherent in it but also determine its process of social growth and cultural evolution [

30].

Concerning the presence of heritage education in formal education, Martínez-Rodríguez and Fontal [

32] analyze how it has been addressed in primary education. Heritage is a relevant subject in the educational curriculum [

33] and it can be found in several areas of knowledge, including social sciences and arts education. Nevertheless, as the latter subject is optional, cultural heritage content may or may not be taught, with this decision consigned to local authorities and schools [

32]. Despite this, the sixth objective in the section on heritage in the arts education subject in the primary education curriculum does mention cultural heritage content. Martínez-Rodríguez [

34] agrees with this approach and recognizes from a music-based perspective the extent of the content related to musical heritage and suggests that the skills-based educational model of the LOMCE (Organic act to improve the quality of education) [

33] requires a new focus within arts education whereby the purpose of cultural manifestations is to encourage the enjoyment of the cultural heritage associated with them. The views put forward by Fontal and Martínez-Rodríguez [

35] argue that heritage, and specifically musical heritage, is a source of knowledge, and help to understand the need to include it as a mandatory principle in the curricula of several educational stages.

For the above-mentioned reasons, and as heritage plays a key role in social, cultural, and economic development, this study was conducted to learn the significance and importance preservice teachers studying a degree in primary education attribute to musical heritage as a representative element of traditional popular culture and a factor contributing to development. This general objective is divided into the following specific objectives.

- −

SO1: Discovering whether the preservice teachers recognize music as part of intangible cultural heritage and the value they attribute it as an expression of culture.

- −

SO2: Evaluating the knowledge and training the students consider they have concerning the value of music in shaping cultural identity.

- −

SO3: Learning the teachers’ opinions on including musical heritage in the school curriculum.

- −

SO4: Evaluating the students’ knowledge of the importance of preserving musical heritage as a sustainable development resource and the actions they would perform to ensure this preservation.

2. Method

This non-experimental descriptive research conducts a statistical descriptive analysis. Two variables were measured in this field study: (1) music as intangible cultural heritage and a reflection of cultural identity, and (2) the dissemination and protection of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable development resource. The statistical analysis was performed using the software IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 [

36]. The techniques and statistical tests employed were as follows:

The description of qualitative variables with frequency and percentage tables. The results are presented as bar charts for more clarity. The mean value is included in the Likert items.

The questionnaire reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency. A value above 0.60 indicates acceptable reliability, above 0.80 good reliability, and more than 0.90 very good reliability.

Associations between two categorical variables were tested using the chi-square test of independence. Besides providing the p-value to determine significance, this test shows adjusted standardized residuals (values similar to Z of the normal distribution) where the indication of correlation justifying significance is that the residuals are ≥2.

This analysis was completed with the value of Cramer’s V coefficient (similar to Pearson’s, but specifically for this type of variable) to quantify the correlation magnitude. In these inferential statistical tests, it is considered significant when p < 0.05 (c.l. usual 5%) and highly significant when p < 0.01 (c.l. 1%).

The sample comprises a group of n = 202 students in the fourth year of their teacher training degree at the University of Zaragoza (UZ) and the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM) who gave their consent to answer an online questionnaire. The selection of the sample was intentional and non-probabilistic.

An ad hoc questionnaire consisting of fifteen items was designed as a data collection instrument (

Table 1) and prepared on the basis of the theoretical review outlined in the introduction and the research related directly to the study variables. Especially relevant in this regard are the contributions made by Sarfson [

37] on artistic and musical didactics in teacher training; by Fontal and Marín [

38] on heritage education as a way to enhance the artistic manifestations of the past; and by Bigenho et al. [

39] on the relationship between music and cultural heritage.

The data collection instrument is underpinned by the contributions made by Fernández et al. [

40] on the assessment of heritage education skills in university students; the study by Carrillo and Vilar [

41] on the self-perception of music teachers in primary and secondary education; the work by Barrios [

42] in the context of the pedagogical research project for teacher training on the legacy of musical heritage; and the research by Nadal and Rodríguez [

30] in which they perform a didactic analysis of heritage education in preservice teachers. Similarly, the research conducted by Marín and Fontal [

43] on the perceptions of heritage held by Spanish compulsory secondary education students and the study by Fontal et al. [

44] on the social perception of heritage were also essential.

The instrument comprises fifteen items of compulsory questions in three structural blocks. The first block corresponds to an ordinal Likert scale with two items with three and six response alternatives (items 1 and 8, respectively). The second block corresponds to the same type of scale but with five response alternatives, in which 1 equals very low and 5 very high, based on the way each question is structured. This section is included in the previous one and comprises ten exploratory questions. The students’ level of knowledge of musical heritage, the teaching and dissemination of this area of intangible cultural heritage, the preservation of the assets forming it, and the relationship between heritage and identity was explored in both sections. The third block comprises open-ended questions to discover the participants’ opinions on what musical heritage represents, how preservice teachers act with regard to ways in which cultural legal is preserved, and the importance they attribute it as a sustainable resource. The aim is also to gain an understanding of the emotions cultural heritage triggers in the students.

These items are also organized into four thematic blocks. Block 1: Knowledge of musical heritage. Block 2: Musical heritage and identity. Block 3: Curriculum and heritage education. Block 4: Disseminating and safeguarding musical heritage. The following table shows the distribution of the items in each of the structural and thematic blocks (See

Table 1).

The instrument was validated by expert opinion considering element equivalence, objectives, clarity, appropriateness, and coherence [

45]. The outcome showed that the level of agreement between experts was acceptable. As a result, the instrument was modified for clarity.

Concerning internal consistency, the instrument’s reliability was considered acceptable on the total scale of twelve response items (from 1 to 12); open-ended items 13, 14, and 15 were excluded from this test. A Cronbach’s alpha index of 0.740 and an intraclass correlation coefficient with a confidence interval of 95% were obtained in the reliability statistics (see

Table 2). After making the corrections and adjustments suggested by the experts, a pilot test was conducted with the participation of 110 students. The results corroborated the validity of the instrument.

3. Results

The results obtained for SO1, aimed at discovering whether preservice teachers recognize music as part of intangible cultural heritage and the value they attribute to it as an expression of culture, show that most of the respondents (198) provided only one response of the three possible options. For 72.2% of them, music is part of intangible cultural heritage. However, 19.7% include it in both tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and 16.7% in natural cultural heritage.

A high level of agreement was found in the responses concerning the extent to which music is considered a part of cultural heritage. It was considered high by 31.8% of students and very high by 61.2%. In other words, only 7% did not rate it. The total mean (on a scale of 1 to 5) of the extent of agreement is 4.54 points.

Regarding SO2, which explores the knowledge and training students consider they have concerning music as heritage and its value in shaping cultural identity, 69.2% believe musical heritage should evolve. Out of this number, 29.4% think it should do this constantly. In contrast, 24.4% have no clear opinion on the matter. Only 6.5% believe it should not evolve or should evolve slightly.

Related to whether heritage is enhanced with new additions or remains static, 77% of the students believe it is enhanced. Out of this percentage, 40% assert it is boosted with new additions. For 33% of the questionnaire respondents, meanwhile, this happens continuously. Only 5.5% believe it is not enriched and 21% do not have a conclusive opinion.

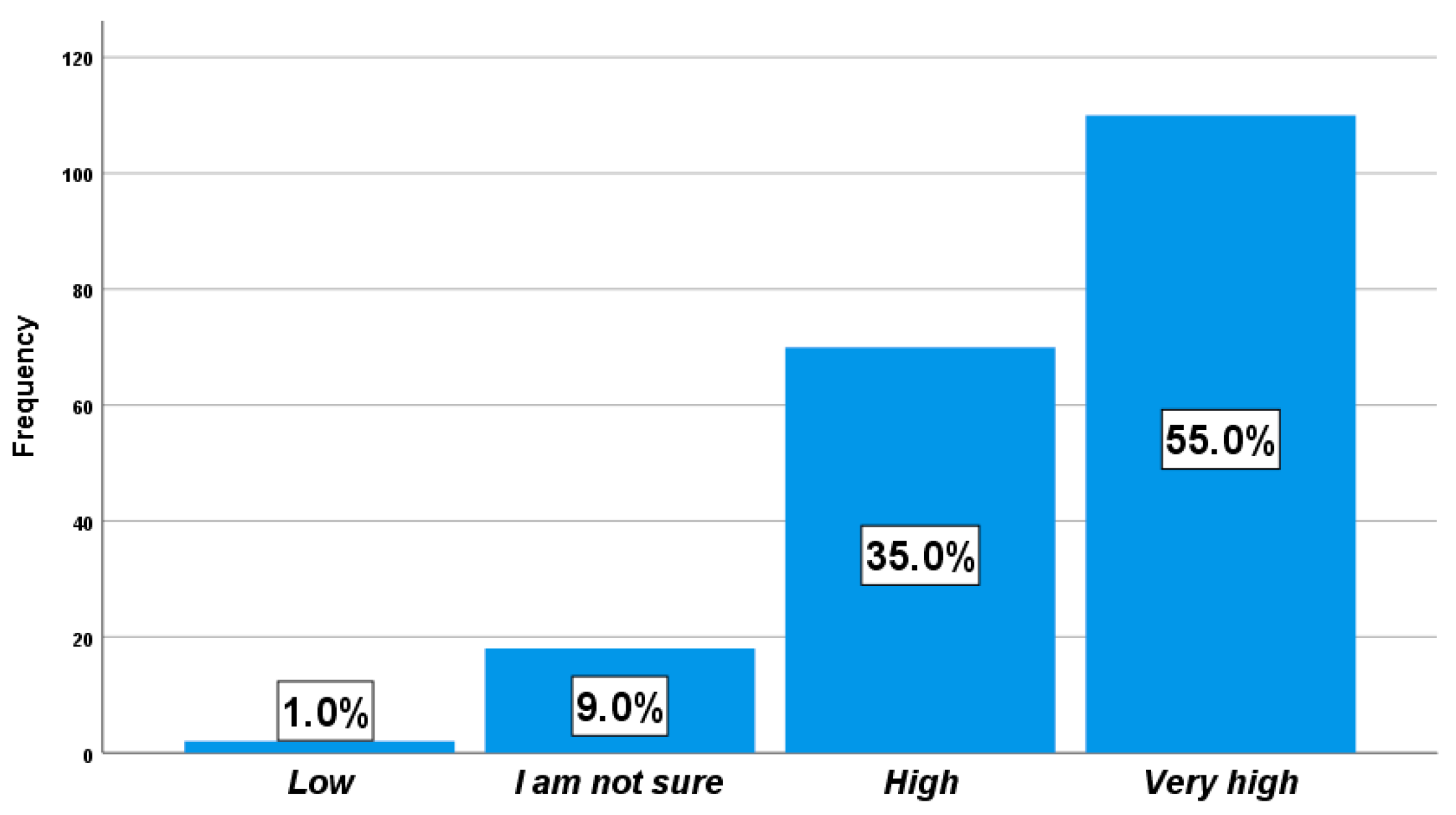

For 55% of the respondents, music makes it possible to establish links with a territory to a high extent. While 35% of the students think the link between music, heritage, and identity is high. Concerning the data obtained, the mean of the extent of agreement is 4.44 points out of 5 (See

Figure 1).

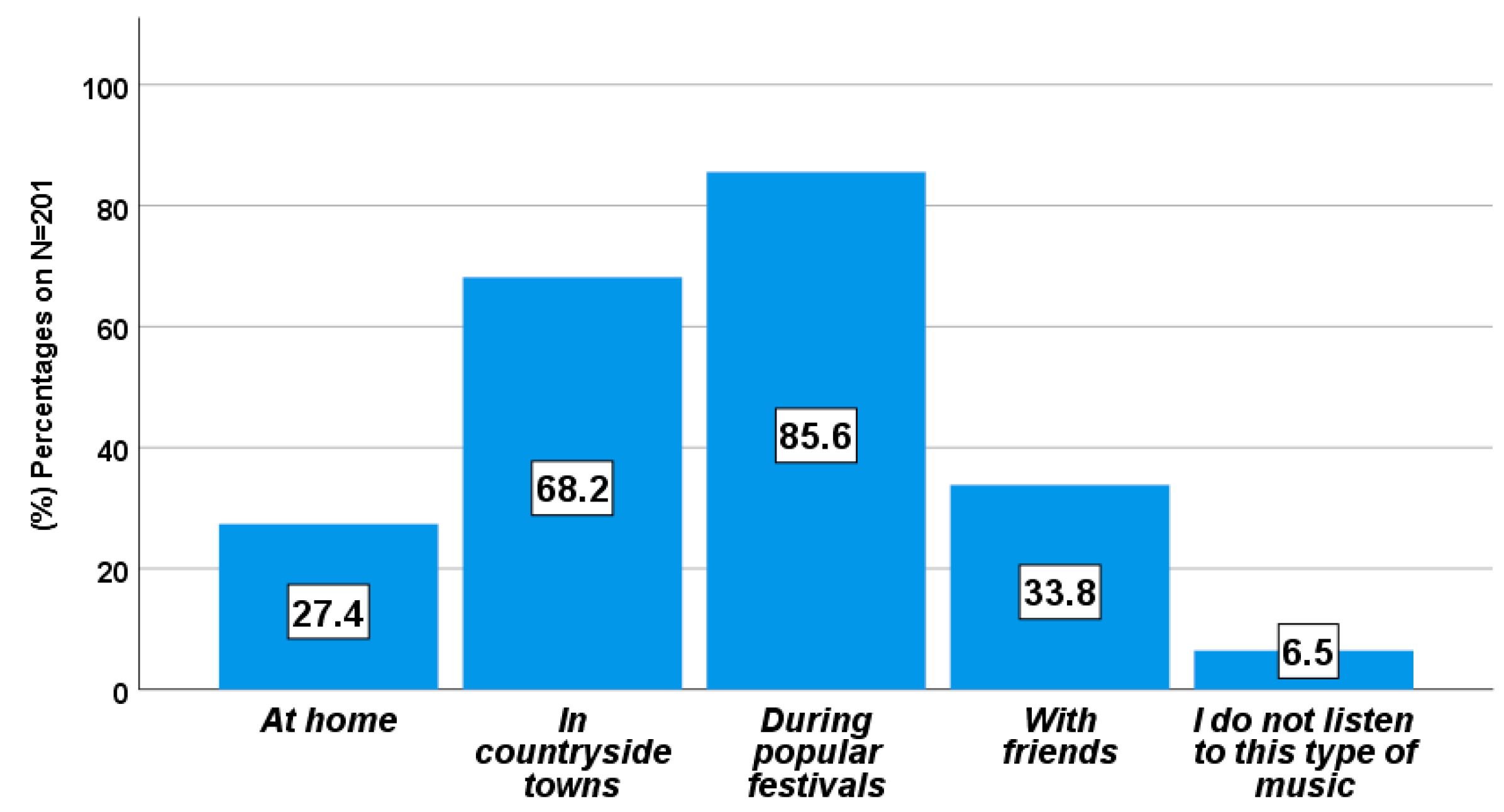

For the item asking about the place where they usually listen to popular traditional music, almost all the students, represented by 85.6% of the 201 participants, agree that the location is popular festivals (See

Figure 2). This type of heritage artistic manifestation is only listened to by 68.2% when they are in countryside towns for tourism or family reasons. Besides the above, 33.8% say that gatherings of friends are organized during popular festivals at which this type of musical expression is heard. Traditional music is usually listened to at home by 27.4% as their parents or grandparents play it. They also say it has become a recurrent practice in their homes. In contrast, 6.5% of the respondents admit they do not listen to this type of music.

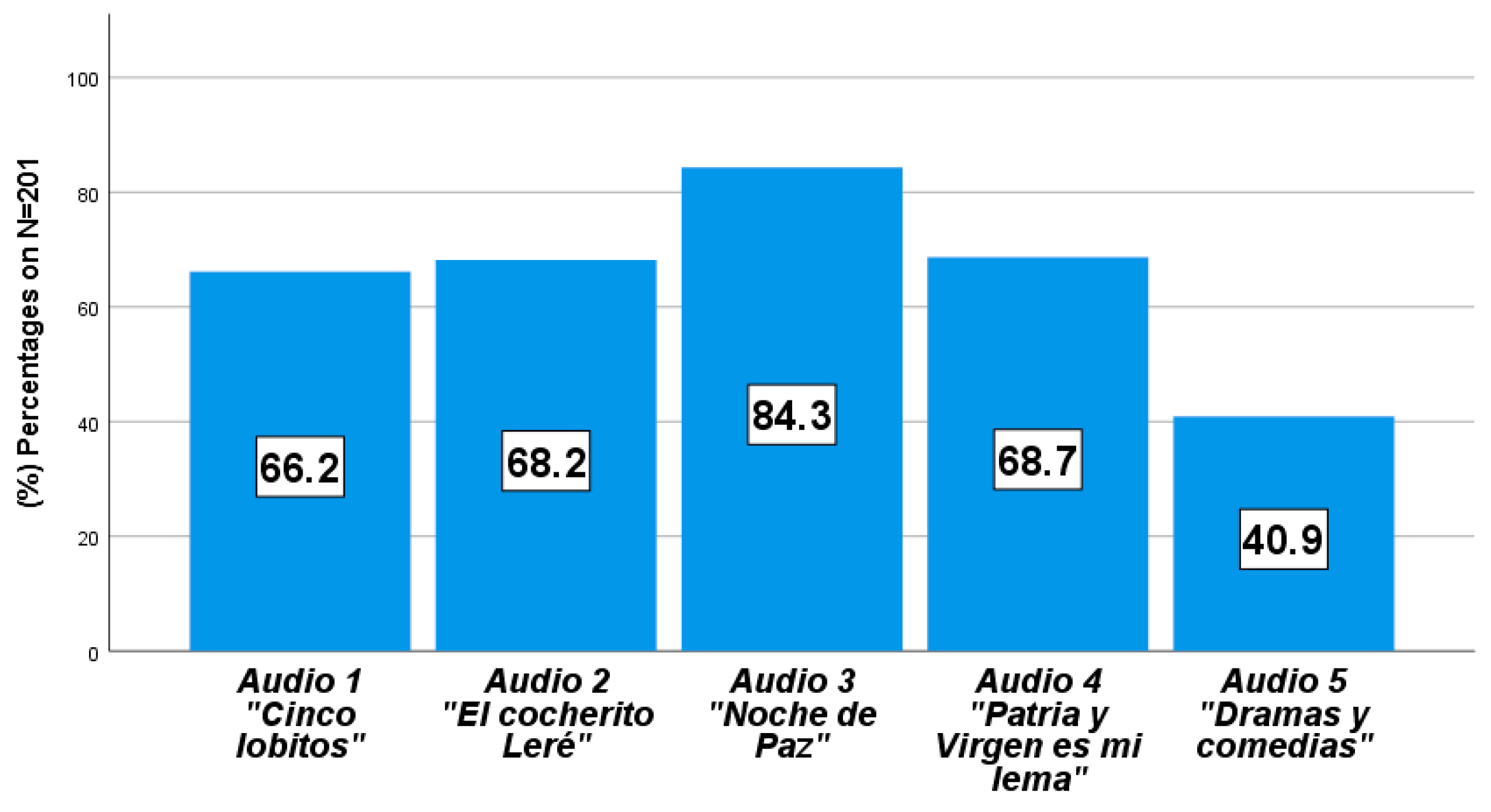

Concerning the importance of keeping musical heritage alive, 59.5% rate this as very important alongside another 36.5% that consider it important. Consequently, the total mean of the sample is 4.55 points out of 5. Barely 1% considered it not very important. After reproducing five audio clips, the students were asked whether they belonged to musical heritage or not. The sense of belonging was highly attuned in general (See

Figure 3). They include no. 3, “Noche de paz,” voted by 84.3% of the sample, followed by no. 4, “Patria y virgen es mi lema,” with the agreement of 68.7%, and no. 2, “El cocherito leré,” with a representation of 68.2% of the respondents. At the other end of the scale, the least voted was no. 5, “Dramas y comedias,” by 40.9%.

Concerning the relevance of musical heritage in the curricula of the educational stages (See

Figure 4), the responses obtained clearly show that over half of the respondents believe they are relevant in all stages (56.2%), 16.9% say they are relevant in both preschool and primary education, and 14.9% answer in both primary and secondary education. Only 1% believe that the stage where inclusion of this type of heritage is most necessary is preschool.

Concerning the relevance of the need to include musical cultural heritage content in curricula, this is relevant for 50.2% of the respondents. For 27.4%, this is very relevant. These results lead to a relevance level of 4 points out of 5.

The role education plays in safeguarding musical heritage is important or very important for 83.6% of the participants (See

Figure 5). Consequently, the mean of this level of importance is 4.17 points out of 5. Barely 1% think it is not very important, and 15.4% do not have any opinion as they are not sure.

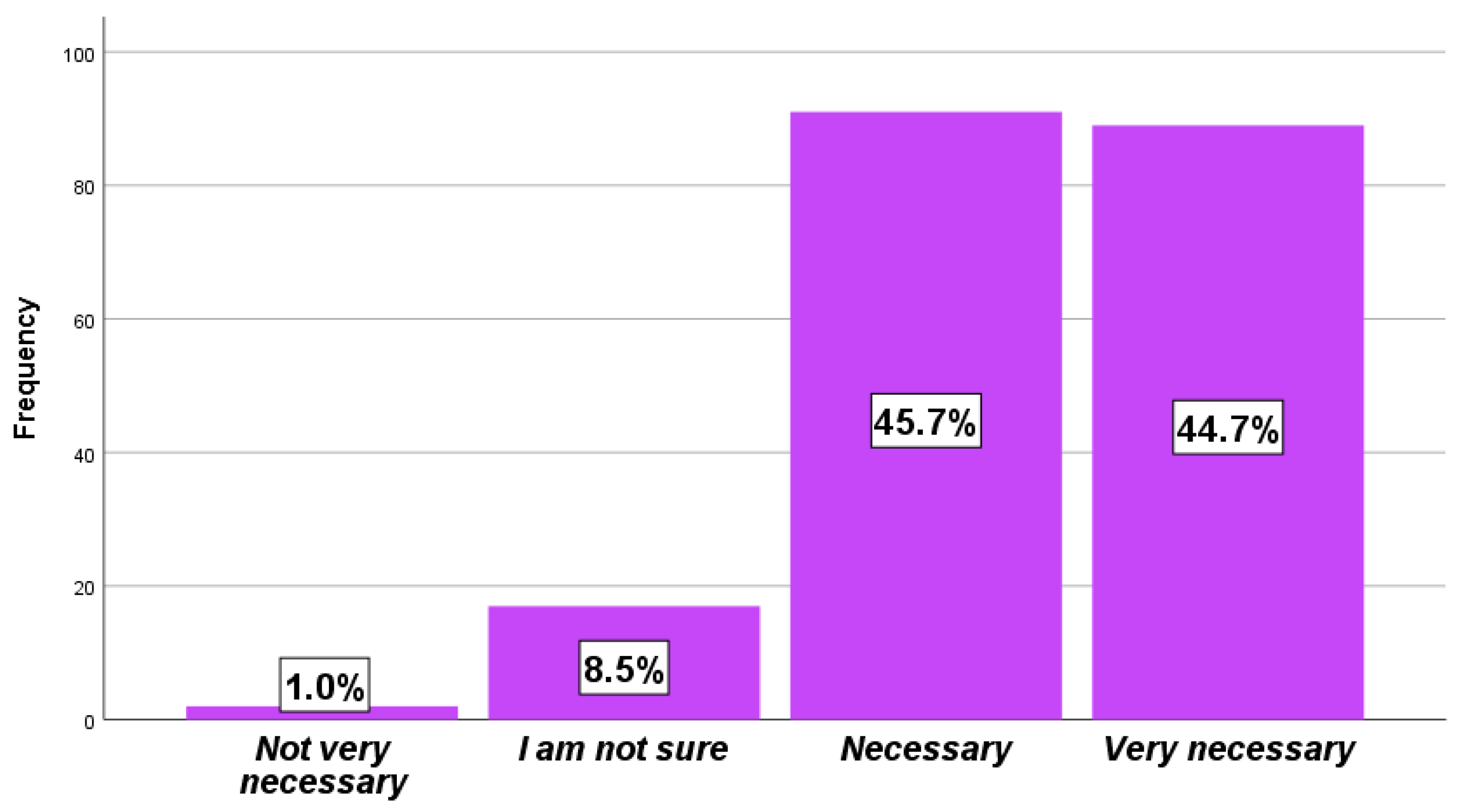

A similar result appears in the answers given on the need to spread awareness of musical cultural heritage (See

Figure 6). Disseminating musical heritage is very important for 44.7%, while for 45.7% it is important. The results involve obtaining a mean of 4.34 points out of 5.

Significant results were obtained in the analysis made to determine the correlation between the items. A high correlation was found between item no. 2 and no. 7 (

p < 0.001) with moderate intensity (0.33). From the data (See

Table 3), we can observe (a) participants who consider it very important to preserve cultural heritage associated with a very high rating of music as cultural heritage (48.5%); and (b) participants who consider it is important to keep cultural heritage alive associated with a high rating of music as part of cultural heritage (19%). In other words, the trend is that the higher the rating of music belonging to cultural heritage, the more important keeping musical cultural heritage alive is, and vice versa.

A considerable (0.40) and very highly significant (

p < 0.001) correlation between both variables is observed in the correlational analysis between items 10 and 11 (See

Table 4). The data show that as the importance of education as a crucial factor in promoting and safeguarding musical cultural heritage increases, so does the need to spread awareness of it.

Open-ended items 13, 14, and 15 cannot be analyzed with quantitative statistics; for this reason, they are interpreted using qualitative data interpretation methods. Concerning item 13, which aims to gain an understanding of the emotions musical heritage triggers in students, the works included in item 12 create contradictory feelings in them. This question received a total of 172 responses. Most of the respondents link audio clip 1, “Cinco lobitos,” 2, “El cocherito leré,” and 3, “Noche de paz,” with filial feelings, festivals related to Christmas and their childhood, formal schooling, their peers, and also a territory. They recognize that they “produce pleasant sensations” and cause strong emotions as they remind them of “loved ones that are no longer here”. All the students who gave their opinion on audio clips 1, 2, and 3 agree with the above-outlined criteria. Nevertheless, in twenty-three responses they say that the audio clips “remind them of heritage traditions” and they are aware of the link they establish with identity.

Of the total of 172 responses provided by the respondents, only two students claim that audio clip 3, “Noche de paz” remind them of “religious traditions,” creating a link with popular religion. According to two of the respondents, four of the first audio clips are “musical cultural heritage works as they have been conveyed to several generations” and they already form part of traditions. Concerning audio clip 5, “Dramas y comedias,” only two students say it reminds them of “fun and happy times”. They also claim that they listened to it when with friends and that the song represents a recent age that also makes them think of the “empowerment of women, freedom of expression”. They classify it as a “revolutionary song”. In general, they believe it is a “reflection of an era” but not a part of musical heritage.

On item 14, on the importance of traditional musical heritage and the need to preserve it, a total of 187 of the 202 respondents gave a response and believe that it should be preserved as “it is a reflection of an era forming part of history,” a “cultural manifestation of the situation of a moment in history,” and a “conveyor of customs and traditions that must not be lost as they form part of our collective identity”. They believe that “it is an identity element that links us to a group or collective”. Besides establishing a connection with individuals, it forms part of a common feeling, based on knowledge and customs that build culture and generate cultural traits that vary from one society to another; it also has an instructive value in terms of our history, since it provides us with information on the social or political aspects of a historical period, context, or social reality.

A total of twenty of the students who provided answers to this question believe it is important to preserve musical heritage as it is essential for conveying our cultural legacy to current and future generations. They consider “it is an identity symbol that identifies us, sets us apart, and shows how various historical ages and periods have evolved and changed”. We can infer from the responses that the students consider musical heritage as an economic resource that must be preserved since it contributes to the development of territory and is a source of employment. Similarly, they recognize that tourism and heritage are very closely linked. Of all the respondents, fifteen did not respond to the item and two gave no opinion on the matter as they claimed not to have any knowledge of the importance of preserving cultural heritage.

There were 177 responses concerning the actions they would perform as future teachers to preserve musical heritage. Of these, a total of 160 of the respondents recognize the importance of heritage education in various educational contexts. They say that the heritage issue “should be more present in the school curricula of the various educational stages”. To sum up, they point to education as a key factor in preserving cultural legacy. Furthermore, ten of the students refer to “heritage as an educational resource and a primary source of knowledge with a close tie to history”. For that reason, teachers must systematically use it and increase its presence in their classrooms, linking it to the opportunities afforded by film, dance, and theater. They believe that music is significant in the first educational stages as it encompasses a playful component that teachers should take advantage of. Nevertheless, they conclude that its presence in the curriculum in the other educational stages is pertinent. They emphasize that “quality education needs to benefit from the opportunities and contributions cultural heritage provides”.

A sample of twenty-five students believe that communication plays a determining role in preserving musical heritage. In their opinion, there should be “competitions, festivals, and projects”. Furthermore, “popular festivities linked to this type of heritage should be more publicized”. Four students say that significant learning and, specifically, “service learning, is a method that directly contributes to establishing a link between students and heritage”. It is a way to develop values and respect for cultural heritage; they claim people do not value what they do not know. A total of twelve students agree it is necessary for “the media to become more involved and committed”. For the students, radio and television should be aware of the need to preserve cultural legacy as a source of wealth.

4. Discussion

As a part of intangible cultural heritage, music is a source of knowledge and plays a major role in conveying social, cultural, and economic values; for this reason, it is important to preserve it as a sustainable resource for development [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, knowing what preservice teachers think about the sustainability, importance, and preservation of musical heritage as a sustainable resource is essential to devise plans and educational strategies that help further knowledge of cultural legacy.

The results obtained in relation to SO1 show that the students identify music as an intrinsic part of intangible cultural heritage. Despite this, a group of respondents did not appropriately identify this type of heritage. The results provide striking data on the knowledge of heritage at this educational level. This fact is concerning, since people need to know about a heritage resource in order to value and preserve it, and the role of education in this is vital [

16,

17,

18,

46]. Concerning recognizing music as a part of cultural heritage, most of the students consider it a cultural expression and an integral part of this heritage. They believe it is an essential component and especially significant as it reflects an era and conveys social and cultural values. These criteria coincide with other studies connecting music with social events in history and considering it as part of the cultural heritage of countryside towns [

47], and as a social and cultural construct [

48,

49].

Concerning SO2, most of the students recognize the link between music, heritage, and identity. Musical heritage reflects a social and cultural reality, and it is also a conveyor of cultural values defining a territory. The results obtained are connected with studies outlining that heritage establishes connections between historical memory and the present and helps interpret and leverage the knowledge that is a reflection of cultural identity [

50]. Similarly, heritage expresses identities and has a bearing on how citizenship is structured by recognizing sameness and otherness [

51,

52]. These approaches are rooted in the diversity of culture, the plurality of identities, and shared world heritage [

53], and they coincide with UNESCO’s criteria [

54].

The results obtained provide favorable data for SO3, since over half of students are aware of the need to include musical heritage content in the curriculum. Consequently, they believe that including heritage content in the curricula of the various educational stages is relevant and very relevant. They believe musical heritage is a subject that should be permanently present in school curricula as it plays an essential role in conveying values, shaping identities, and developing emotions. These perceptions consider the educational value of heritage and the connections between emotions, territory, and citizenship [

17,

18,

19]. They are also related to the contributions made by other studies on heritage education as a means of valuing cultural legacy [

38,

46].

It is important to highlight that the need to include musical heritage content is based on the subject being more present in arts education and social sciences and less represented in other areas [

32]. These opinions coincide with those put forward by López [

55] on music and heritage being necessary and essential in the process of knowing, understanding, and spreading awareness of cultural legacy [

56,

57,

58]. According to the students, the primary education curriculum contains more heritage content. Besides this view, other studies detail that it is still not present enough, nor approached the same way in the remaining educational phases [

59]. Almost all the respondents recognize the value of heritage education as being fundamental in protecting musical heritage. Addressing heritage content in education as a way to learn about and preserve cultural heritage is rated as very important. Including heritage content in education is an issue that has been approached from a variety of perspectives in the Spanish context [

14,

15,

22]. The subject is also represented in other latitudes, such as the research outlining the lack of heritage education experiences in teacher training in Mexico [

59].

In the responses on the importance of preserving musical cultural heritage as a sustainable development resource (SO4), the students recognize that heritage preservation is vital as it reflects cultural identity and plays a major role in developing identity values. This opinion agrees with those held by Cuenca et al. [

18] and Infante and Hernández [

60]. These authors believe preserving heritage is extremely significant as it represents a territory, conveys cultural values and knowledge, and is an intrinsic part of history. They are also of the opinion that heritage allows us to identify and differentiate cultures and that it has an invaluable economic component for development. The above views agree with those put forward by Rodríguez and Solís [

61] when they state that it is a shared collective legacy giving those that have it a feeling of identity. UNESCO [

1] shares this idea as it considers that cultural manifestations are an integral part of the cultural heritage of communities and, therefore, that they are conveyors of an identity dimension. They are also linked to the thoughts of Jiménez et al. [

15] as they consider that intangible cultural heritage fosters intercultural dialogue, thereby encouraging respect and understanding among peoples.

Preservice teachers believe heritage is an invaluable resource that contributes directly to sustainable development. Besides its educational potential and important role in developing skills and values, it is an economic factor in people’s social and spiritual development. Concerning this point, the students’ views correspond to those expounded by Zaman [

62], who considers that correct organization and valuing of cultural heritage require a market whose goods and services directly contribute to the community the asset belongs to, which cannot occur unless the cultural element is given priority first. In this regard, Bashi [

11] believes that heritage is a source of wealth boosting the economies of nations. These are all reasons to devise actions to ensure its preservation. Along the same lines, Molina [

6] considers that the terms culture and sustainability are interrelated.

Concerning the views of the preservice teachers and the trinomial established between heritage, preservation, and sustainable development, revisiting the contributions made by Soini and Dessein [

63] may prove useful. These authors believe that culture is a resource that should be preserved and distributed to everyone equally. In cultural management, heritage needs to be integrated with sustainability. Preservice teachers’ opinions on the actions they should perform to preserve cultural heritage and, specifically, intangible cultural heritage, are based on communication, dissemination, and promotion actions as a means of gaining knowledge about and protecting cultural legacy. They consider that any actions implemented should aim to develop dissemination and awareness programs focusing clearly on heritage education. These considerations coincide with those put forward by Cañete et al. [

64], namely that promotion is a participatory process establishing a link between people and their culture.

The emotions and heritage binomial are other aspects the students raised as a means of contributing to cultural legacy preservation. Cultural heritage, and specifically musical cultural heritage, facilitates the development of emotions [

65]. It also positively and directly influences and contributes to the teaching–learning process [

66]. Similarly, preservice teachers highlight the need for actions leading to more societal involvement; these considerations correspond to the content of the National Plan for Preventive Preservation of the Ministry for Culture of Spain [

67]. According to this document, society needs influencing to encourage more involvement and awareness of cultural heritage to ensure it is protected. Based on this perspective, realizing that culture begins in consciousness is pertinent [

68]. This leads to understanding the importance of instilling in individuals the need to safeguard heritage. The results obtained also show that the students give special significance to the use of information and communication technologies as a resource that directly contributes to knowledge about heritage and its dissemination. The contributions made by Vasile et al. [

69] are relevant here as they posit that digital technologies are forms of participatory cultural consumption with major significance in the process of conveying and valuing heritage. These considerations also correspond to the ideas mentioned by Vicent et al. [

70] as they think this type of resource makes the past more approachable in a comprehensible and emotional way, and it helps develop students’ critical thinking.

5. Conclusions

Musical heritage is an invaluable educational resource as its integrating and interdisciplinary aspects translate into opportunities for covering it in the classroom [

17,

18,

19]. However, its potential is not limited to the educational or axiological sphere, or the development of emotions; instead, it also has an inherent economic dimension that contributes to social development. For this reason, the sustainability of musical heritage is a crucial factor impacting several aspects or spheres of society and requiring preservice teachers’ knowledge and appraisal [

70,

71].

Due to its nature and content, heritage is a topic that fosters teaching committed to the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Cultural legacy is a resource that helps develop sustainable cities and communities and to educate their citizens to become critical and committed to both their era and social and economic development [

20,

69]. Along these lines, heritage education imparted at the various educational levels plays a vital role in developing a social commitment that leads to a better and more sustainable world, implementing quality education, and safeguarding heritage. All the above justifies the study’s importance and relevance. Learning about and studying the knowledge preservice teachers have of musical heritage and its value as a sustainable development resource is fundamental for devising educational strategies that contribute to better knowledge, understanding, awareness-raising, and respect for cultural heritage. It has to be given prominence from the start of the university degree so that preservice teachers will then put it into practice.

This study has highlighted the importance students place on heritage as an educational resource. The data lead us to conclude there is a need to implement educational strategies to contribute to more knowledge of musical heritage in preservice teachers. Although the respondents share the view that musical heritage has an educational value, contributes to the development of identity values, and needs to be included in school curricula in the various educational stages, they also believe it is important to explore the recognition and identification of the assets forming this heritage. Another requirement is that teachers emphasize the importance of the sustainability of cultural heritage and the contribution it makes to development. From all of the above, we can conclude that teachers need to promote heritage education and have a responsibility for doing so. The results also lead to questioning the methods, strategies, and methodologies used in the heritage teaching–learning process.

The study results have provided an insight into preservice teachers’ knowledge of cultural heritage, its sustainability, and involvement in development. It is a first approach to the subject with a descriptive, accessible focus, which informs the tutors at the studied universities and allows them to devise practical strategies to counteract the deficiencies detected.

Since it is an exploratory study, the work presents a limited sample (

n = 202) from two Spanish universities. Future research that addresses musical heritage as a vehicle for sustainable development should expand the sample field, collecting a representative sample of students from Spanish universities or even internationally. At the same time, it would be interesting to establish differences between students with and without musical training, as well as to compare the results of this study with the perceptions of active teachers. Another limitation of the study is related to the national educational curriculum (LOMCE) [

71]. The imminent change of the educational law (LOMLOE) [

72] will generate changes in the curricular contents and the way of approaching them, which will have implications for the teaching–learning of musical heritage. Future research should analyze the new educational curriculum to find out the status of musical heritage education.