The Influence of Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance on the Information Dissemination Mechanism in Virtual Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Classic Trust Theory

2.2. Trust in the Network

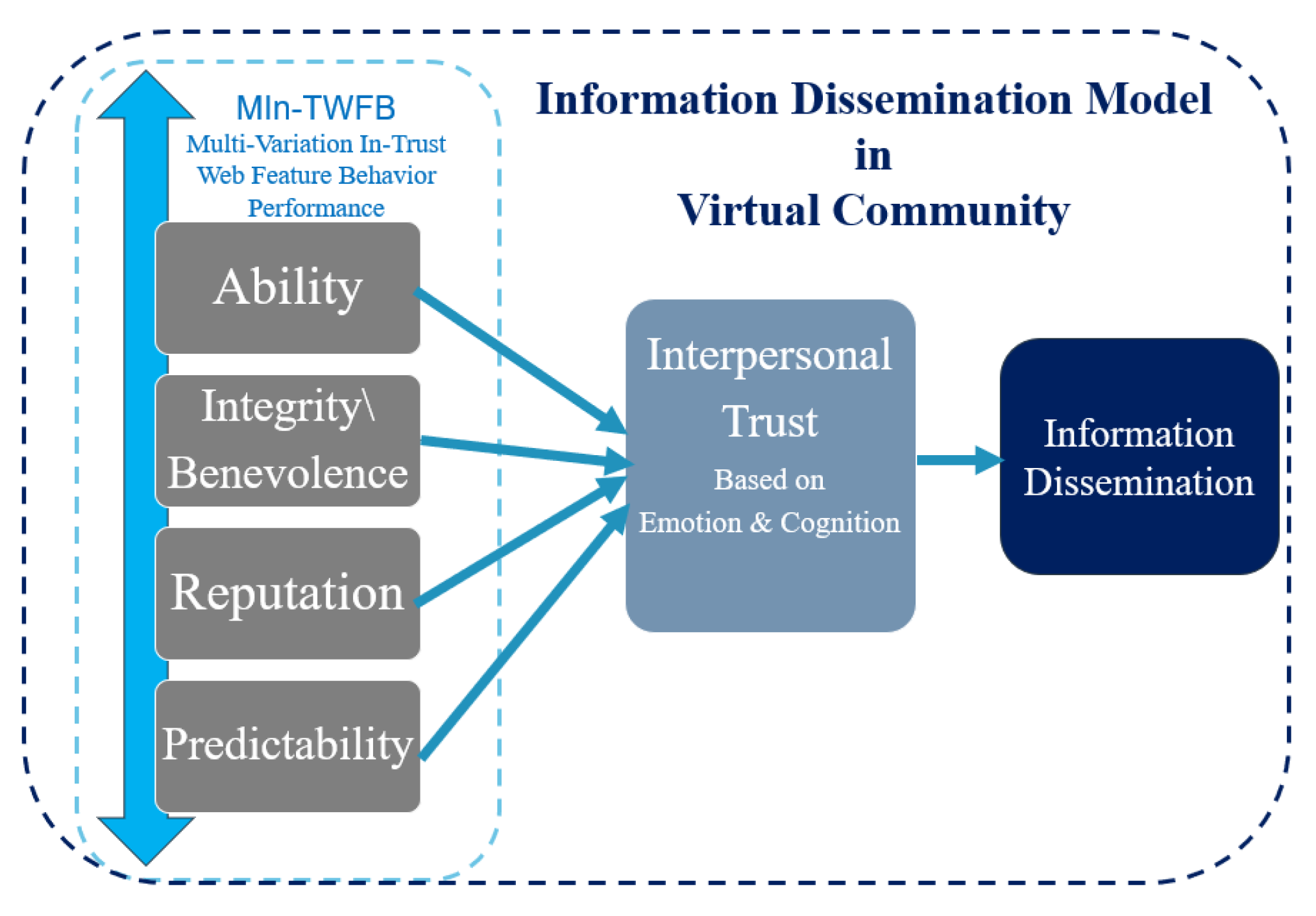

2.3. The Research Framework Model

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Hypothesis Development

3.2.1. The Link between Interpersonal Trust and Information-Dissemination Behaviors in the Virtual Community

3.2.2. MIn-TWFB and Interpersonal Trust in the Virtual Community

- (1)

- Ability component of MIn-TWFB and interpersonal trust in the virtual community.

- (2)

- Integrity/benevolence component of MIn-TWFB and interpersonal trust in the virtual community

- (3)

- Reputation component of MIn-TWFB and interpersonal trust in the virtual community.

- (4)

- The predictability component of MIn-TWFB and interpersonal trust in the virtual community.

3.2.3. Trust-Supporting Components of MIn-TWFB in the Virtual Community

4. Research Methods

4.1. Survey Design

- (1)

- When the questionnaire survey was designed for MIn-TWFB, the trust-supporting components of MIn-TWFB referred to items from those relevant studies, each part composed of four to five items. The intertextual description of the measurement items that came from the reference materials for the same latent variable was shorted. Then, each measurement item was modified or amalgamated to meet our work according to the virtual community (VC) situation and Chinese culture characteristics. In such a way, the accuracy and adaptability of the items’ content expression were improved.

- (2)

- Experts and scholars in management, information, and other fields were invited to review the preliminarily designed questionnaire.

- (3)

- Since young people are the main character group of the network, undergraduate and graduate students from a university were invited to conduct a small-scale pre-test survey on the questionnaire.

- (4)

- Combined with the suggestions from a group of experts and pre-test feedback results from respondents, the original questionnaire was amended again. Then, the formal questionnaire was finally formed after repeated refinement, which included six latent variables and 25 observation variables. Table A1 in Appendix A shows the final measurement items and literature sources of each variable.

4.2. Sample

- (1)

- Respondent composition: The proportion of males and females was 59.1% and 40.9%, respectively.

- (2)

- Age composition: There were 68.1% of respondents aged 18–39, 22.7% aged 40–49, 4.5% aged 50–59, and 4.5% aged 60 and over. The age range of 18–49 years old accounted for 90.8% in total.

- (3)

- Education composition: High school (including technical secondary school) and university education (including junior college) accounted for 55.50% in total, and a master’s degree or above accounted for 42.3%. Over 97.8% of respondents had obtained a bachelor’s degree (including education experience equivalent to bachelor’s) or above.

- (4)

- Registration time composition: This comprised the length of time respondents’ had been registered in various online communities, with 13.6% for less than half a year, 12.1% for 0.5–2 years, 19.7% for 2–5 years, and 54.5% for more than 5 years. A total of 74.2% of the respondents had used the virtual community for more than 2 years.

- (5)

- Honorary qualifications composition: This comprised the respondents’ qualifications in various online communities, with senior or honorary members accounting for 9.1% and ordinary members accounting for 90.9%.

- (6)

- Usage composition: This comprised the respondents’ visiting frequency to various online communities, with 31.8% visiting less than or equal to 6 times/week, 15.2% 7–10 times/week, and 53.0% over 10 times/week. Furthermore, 36.4% visited less than 30 min/time, 34.8% visited 30–60 min/time, and 28.8% visited more than 60 min/time. A total of 68.2% of the respondents visited the virtual community 7 times/week at least, and 63.6% of the respondents spent at least 30 min at a time in the virtual community.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

- (1)

- Applicability test of MIn-TWFB (Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance). The four dimensional components of MIn-TWFB were valued based on principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimension of the data set for the applicability test. The result of the KMO value was 0.809 and the χ2 statistical value of the Bartlett sphericity test was sig 0.000, indicating that it completely met the feasibility standard of operating PCA.

- (2)

- PCA of MIn-TWFB. The four principal components could be extracted from data in the online community through PCA. The results are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Table 1 shows that there were four factor values of features greater than 1, and the cumulative variance contribution rate of the four reached 84.60%, which indicates that almost the original survey data could be perfectly reflected [80]. The number of factors was four more than two, in which the first factor’s variance interpretation rate was 49.11% (<50%) [83,84] and its variance interpretation rate after rotation was 25.51%. This means that the common method bias was not obvious and was acceptable. After rotation with the maximum variance method, the loading of each observed variable on its factor was more than 0.6 (>0.6). As shown in Table 3, the factor structure was relatively clear, which indicates that the convergence validity of the same dimension was acceptable, and the differential validity of the scale was also acceptable.

- (3)

- The common degree (common factor variance) of MIn-TWFB. Commonality show the proportion of each item’s variation that can be explained by common factors, so more commonality usually means not only more common characteristics that can be measured with common factors, but also more influence [85]. All commonality (common factor variance) in Table 2 was more than 0.5, and the smallest item of factor 4 was 0.710, which means that the remaining three common factors contributed 71.0% of the P1 variance. All measure items contained in each of these four factors were the originally preset measurement ones, so each dimensional latent variable could be respectively represented by deigned measure items as expected. Then, the designed survey scales of the four dimensional MIn-TWFB were feasible and applicable, describing users’ online community trust behavior reasonably well.

- (4)

- Common method bias test and reliability test of the information dissemination model of the virtual community (VC). This survey process adopted an online questionnaire to collect data, which may have caused common method bias in the research results. The criterion that the correlation coefficient between latent variables not exceed 0.9 indicates that the common method bias was not obvious and acceptable [86]. In Table 4, the correlation coefficient between latent variables ranged from 0.279 to 0.623, far from 0.9, indicating that the quality of the measured data was good. Cronbach’s coefficient (Cronbach’s α) is usually used to assess each dimension or the facet of scale reliability in the factor analysis process. The Cronbach’s α threshold of 0.7 was adopted as the reliability standard [87] and the corrected item total correlation (CITC) was not less than 0.5. The composite reliability (CR) reference threshold was more than 0.6 in the work of Hair et al. [88] and Fornell and Larck [89], and the average variance extracted (AVE) reference threshold was more than 0.5 [80]. The standard loading of each factor, Cronbach’s α, CR, and AVE are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Among them, the six dimensions of the model were ability, integrity/benevolence, reputation, predictability, interpersonal trust and information dissemination. The Cronbach’s α of the six dimensions ranged from 0.876 to 0.947, all of which are more than 0.7. The composite reliability (CR) ranged from 0.816 to 0.951, all of which are more than 0.6, and each CITC value was more than 0.7 as well. The results show that all variables were measured well, the measurement model of this study is reliable, and the questionnaire data had certainly stability and consistency.

- (5)

- Validity test of the information dissemination model of the VC. Convergent validity was confirmed by examining both the indicator loadings and AVE. The standardized factor loading of each indicator ranged from 0.606 to 0.971, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4. All of them were more than 0.50. Furthermore, the AVE ranged from 0.528 to 0.830, both more than 0.50. Such results show that latent variables had good convergence validity. The test results of discriminant validity are shown in Table 4; every square root of AVE exceeded the off-diagonal correlations between the constructs, which demonstrates that the scale had good discriminant validity [82], and the correlation coefficient between latent variables had a significant correlation (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05), which provides preliminary support for the theoretical model and relevant assumptions of this study.

5.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion of Results

- (1)

- Online trust in ability, integrity/benevolence, reputation, and predictability all supported a significant positive effect on interpersonal trust in the virtual community (VC). Each one of the trust-supporting components of MIn-TWFB had a significant positive impact on network interpersonal trust, among which the integrity/benevolence component implemented the most significant positive effect on interpersonal trust (β = 0.375, p < 0.001), and the reputation component of MIn-TWFB supported the second most significant positive effect on participants’ interpersonal trust in the VC (β = 0.275, p < 0.01). Thus, the interpersonal communication and interaction of the VC can be regarded as an expansion of real life. The reputation mechanism of the community management plays an important role for the creation and maintenance of websites. The building of a reputation reward system could help guide the participants according to intersubjectively comprehensible rules to support trust within the VC, and positive feedback to user contributions is also helpful in strengthening trust concerning the quality of the content. According to the building and implementation mechanism of the virtual community, proposing “reputation” as one trust-supporting component of MIn-TWFB is helpful and necessary. The reputation component of MIn-TWFB could compensate for a certain lack of primary information and refer to personal outstanding contributions as well as past behaviors of users within the virtual community. Moreover, honorary recognition in the virtual community also means an expectation about the user’s behavior. However, the ability component of MIn-TWFB supported a significant positive effect on participants’ interpersonal trust in the VC (β = 0.193, p < 0.05) compared to the integrity/benevolence component (β = 0.375, p < 0.001). The above result is consistent with the previous research by Leimeister et al. [28] in the fact that benevolence was more important for the members than the professional knowledge and expertise of their communication partners, which might explain why the members could have a high level of benevolence and at the same time show a lower level of competence to the others. According to the data of the structural equation model (Figure 2), the theoretical constructs of MIn-TWFB were supported by showing that the trust-supporting design components had positive effects on the interpersonal trust within the VC. All of the trust-supporting components of MIn-TWFB, such as ability, integrity/benevolence, reputation, and predictability, were not only positively related to interpersonal trust, but were in line with the interpersonal trust mechanism and social relationship networks of offline society as well.

- (2)

- The relation among every four dimensional component of MIn-TWFB was positive. The significant positive correlation between the reputation component and the predictability component of MIn-TWFB was the most obvious (β = 0.461, p < 0.01), which means that the incentive effect of the community reputation reward mechanism is remarkable. The significant correlation between the integrity/benevolence component and the reputation component of MIn-TWFB was on the second level (β = 0.431, p < 0.05), which means that the online community aligned its moral and ethical values with the offline community. Thus, this verifies the virtual community’s social organization property, and that the interaction of the VC is also a real interpersonal social experience with the network as the intermediary. Finally, this research successfully verified that every relation among the four dimensional components of MIn-TWFB was positively connected; each one of the four dimensional components could complement and interweave one another—in a sense, they all belong to an integrated belief.

- (3)

- Users’ online behavior (based on intrinsic trustworthiness properties) could be perceived and affect interpersonal trust. The path coefficients from the ability component, integrity/benevolence component, reputation component, and predictability component to interpersonal trust were 0.193, 0.375, 0.275, and 0.206, respectively, as shown in Figure 2, which verifies that these four latent variables had a positive and significant effect on the network interpersonal trust. So, people’s online behavior of trust in the VC could be perceived and judged by others. Among them, the integrity/benevolence component had the most positive influence on interpersonal trust (β = 0.375), which could significantly improve others’ trust in one, and the reputation component (β = 0.275) followed just behind. Despite the complexity of the virtual community environment and the concealment of information, users can still form an impression of whether other community members are trustworthy by observing others’ honest and friendly online behavior, reputation, and status in the VC. Obviously, this impression was also affected by expectation of others (β = 0.206).

- (4)

- MIn-TWFB applies influence on network information dissemination through the interpersonal trust in the virtual community. The research found that interpersonal trust and the mechanism of interpersonal trust on behavioral intention also exists in virtual communities, which also generally exist in traditional communities. The working mechanism of MIn-TWFB’s significant impact on network information dissemination (interpersonal trust to information dissemination, β = 0.652, p < 0.001) is the interpersonal trust of the VC. Due to the virtual community informatization characteristics and users’ behavior trajectory digitalization characteristics, individuals’ online behaviors in the VC could be observed, obtained, calculated, and analyzed. Based on the context above, MIn-TWFB was constructed. Then, we explored how users (based on intrinsic trustworthiness properties) are perceived and recognized through a series of trust-related behaviors in the VC. The relation between MIn-TWFB and the interpersonal trust of the VC was studied, which had an impact on information dissemination in the network. This work helps people understand the value of online behaviors; the information of online behaviors has the same social and organizational significance as real behavior in a traditional community.

6.2. Contributions and Implications

6.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ability | A1. The more user posts are authenticated as the essence, the better the performance. | |

| A2. The more users knows about the topics concerning the community, the better the performance. | [5,41,97] | |

| A3. Users are able to demonstrate their ability to analyze and answer questions related to the theme of the forum. | ||

| A4. User are able to publish news or content in a narrative form understandable to others in the virtual community. | ||

| A5. User are able to share complete and comprehensive content in the virtual community. | ||

| Integrity/benevolence | BI1. After coming to this virtual community, users show the behavior of sharing what they know about a topic with others. | [41,76,98] |

| BI2. In the interaction process of the virtual community, users show their efforts to treat other participants fairly. | ||

| BI3. Users are very loyal to the virtual community, showing that they can selflessly contribute their strength to the community construction. | ||

| BI4. Users show behavior of good interaction with other members of the community. | ||

| Reputation | R1. Some feedback or rewards are gained by participating in community activities, which can represent users’ reputation and status in the virtual community. | [5,99] |

| R2. Users show influence over others through their own ideas and opinions. | ||

| R3. Users try to show their behavior in the community that they expect to become the focus of. | ||

| R4. Users’ behavior shows that they are proud to be members of the virtual community. | ||

| Predictability | P1. Users usually show efforts to share information in the virtual community. | |

| P2. Users usually show efforts to invest a lot of time and energy to participate in the construction of the virtual community. | [5,99,100] | |

| P3. Users usually show efforts to actively reply to the posts of those seeking help in the virtual community. | ||

| P4. The content shared by users could be always expected to enrich information and accumulate knowledge in virtual communities. | ||

| Interpersonal trust | T1. Given a featured user’s past excellent performance in the community, I have no reason to doubt his/her ability and information reserve. | |

| T2. I can trust the featured user to share content in the community without causing me more confusion. | [51,66] | |

| T3. In the interaction with the featured user, I think we all benefit a lot. | ||

| T4. My interaction with the featured user in the virtual community has brought emotional investment and enhanced emotional connection. | ||

| Information | ID1. The featured users share their skills and knowledge with others in the virtual community. | |

| dissemination | ID2. In this virtual community, the featured user’s posts always receive active community response. | [41,101] |

| ID3. When I need advice to solve a problem, I may ask the featured user for help. | ||

| ID4. I possibly look forward to the information shared by featured users to my friends. |

References

- Godes, D.; Mayzlin, D.; Chen, Y.; Das, S.; Dellarocas, C.; Pfeiffer, B.; Libai, B.; Sen, S.; Shi, M.; Verlegh, P. The firm’s management of social interactions. Market Lett. 2005, 16, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheingold, H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Huang, L.; Hou, J.J.; Liu, Y. Continuous content contribution in virtual community: The role of status-standing on motivational mechanisms. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 132, 113283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net Information Office Website. CNNIC Released the 47th “Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development”. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/03/content_5584518.htm (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Chiu, C.; Hsu, M.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Motivational affordances and survival of new askers on social Q&A sites: The case of Stack Exchange network. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 73, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, A.C.; Todeva, E.; Carnauba, A.; Pereira, C.; Boaventura, J. Formal and relational mechanisms of network governance and their relationship with trust: Substitutes or complementary in Brazilian real estate transactions. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2020, 22, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.; Villaseor, N.; Yagüe, M. Sustainable co-creation behavior in a virtual community: Antecedents and moderating effect of participant’s perception of own expertise. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Dou, Z.; Hu, Y.; Huang, R. Textual analysis for online reviews: A polymerization topic sentiment model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 91940–91945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.L.; Faraj, S. It is what one does: Why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, F.; González-Cantergiani, P.; Hans, D.; Villarroel, R.; Munoz, R. Identifying opinion leaders on social networks through milestones definition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 75670–75677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Dai, B.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y. Research status and prospect of online social network user behavior. J. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2015, 30, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Online social network influence analysis. J. Comput. Sci. 2014, 37, 735–752. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, P.; Cornelis, C.; De Cock, M.; Silva, P.P.D. Gradual trust and distrust in recommender systems. Fuzzy Set. Syst. 2009, 160, 1367–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.J.; Luo, H.Y.; Lin, X.D.; Yu, S.M. A trust-similarity analysis-based clustering method for large-scale group decision-making under a social network. Inform. Fusion 2020, 63, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, C.; Yu, X. Exploring the differences of users’ interaction behaviors on microblog: The moderating role of microblogger’ s effort. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Croft, W.B.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S. A framework to predict the quality of answers with non-textual features. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–10 August 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.H.; Widowati, R.; Hsieh, Y.C. Investigating online social media users’ behaviors for social commerce recommendations. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P. Online reviews: Do consumers use them? Adv. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, I.L.B. Do consumers always follow ‘useful’ reviews? The interaction effect of review valence and review usefulness on consumers’ purchase decisions. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 69, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Shah, S. Disconfirmation effect on online review credibility: An experimental analysis. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 145, 113519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pa Paioannou, T.; Tsohou, A.; Karyda, M. Forming digital identities in social networks: The role of privacy concerns and self-esteem. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2021, 29, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Vinitzky, G. Social network use and personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; McElroy, J.C. The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.E. ‘I’m a Lot More Interesting than a Friendster Profile’: Identity Presentation, Authenticity and Power in Social Networking Services (October 1, 2005). Association of Internet Researchers 6.0. 2005. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1884356 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Yang, C.-C.; Holden, S.M.; Carter, M.D. Emerging adults’ social media self-presentation and identity development at college transition: Mindfulness as a moderator. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 52, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Augustine, A.A.; Vazire, S.; Holtzman, N.; Gaddis, S. Manifestations of personality in online social networks: Self-reported Facebook-related behaviors and observable profile information. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leimeister, J.M.; Ebner, W.; Krcmar, H. Design, implementation, and evaluation of trust-supporting components in virtual communities for patients. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2005, 21, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, W.; Ma, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. Users’ health information sharing intention in strong ties social media: Context of emerging markets. Libr. Hi Tech 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, B.; Nicholas, S.; Mitchell, R. The value of international assignees’knowledge of interpersonal networks: Knowledge of people, networks and politics and knowledge flows in multinational enterprises. Manag. Int. Rev. 2016, 56, 425–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A. Knowledge sharing in Asia Pacific via virtual community platform: A systematic review. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2019, 15, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yin, J.; Ma, Z.; Liao, M. The influence mechanism of rewards on knowledge sharing behaviors in virtual communities. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Chiclana, F.; Herrera-Viedma, E. Two-fold personalized feedback mechanism for social network consensus by uninorm interval trust propagation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, R.; Kumar, R.; Raghavan, P.; Tomkins, A. Propagation of trust and distrust. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web, New York, NY, USA, 17–22 May 2004; pp. 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F.E.; Battiston, S.; Schweitzer, F. A model of a trust-based recommendation system on a social network. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2008, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Wu, J. Multi-dimensional evidence-based trust management with multi-trusted paths. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2011, 27, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltz, S.R.; Wellman, B. Asynchronous learning networks as a virtual classroom. Commun. ACM 1997, 40, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpande, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roussean, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Carnerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross—Discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridings, C.M.; Gefen, D.; Arinze, B. Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Chang, C.M.; Yen, C.H. Exploring the antecedents of trust in virtual communities. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegelsberger, J.; Sasse, M.A.; Mccarthy, J.D. The mechanics of trust: A framework for research and design. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2005, 62, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoornlall, F.D. An integrative model of organization trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. What trust means in e-commerce customer relationships: An interdisciplinary conceptual typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N.; Qu, T.; Li, Q.H. Trust: A Simplified Mechanism of Social Complexity, 1st ed.; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2005; pp. 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.K., Jr. Toward understanding and measuring conditions of trust: Evolution of a conditions of trust inventory. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Leidner, K.D.E. Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 1998, 14, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Takahashi, Y. Knowledge-sharing mechanisms: Human resource practices and trust. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S. The role of affect- and cognition-based trust in complex knowledge sharing. J. Manag. Issues 2005, XVII, 310–326. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, S.A.; Kowalski, K.B.; Andiappan, V.S.; Parayitam, S. Effect of knowledge sharing and interpersonal trust on psychological capital and emotional intelligence in higher-educational institutions in india: Gender as a moderator. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2021, 268453155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hu, W. Peer relationships and college students’ cooperative tendencies: Roles of interpersonal trust and social value orientation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 656412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y.; Chang, W.Y.; Yen, J. The influence of trust and relationship commitment to vloggers on viewers’ purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Market. Lo. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Jadeja, A. Psychological antecedents of consumer trust in CRM campaigns and donation intentions: The moderating role of creativity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z. Toward the e-loyalty of digital library users: Investigating the role of e-service quality and e-trust in digital economy. Libr. Hi Tech 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Gao, K.; Zhang, S. A Survey on Information Diffusion in Online Social Networks: Models and Methods. Information 2017, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vohra, A.; Bhardwaj, N. From active participation to engagement in online communities: Analysing the mediating role of trust and commitment. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misztal, B. Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Constant, D.; Kiesler, S.S. The Kindness of Strangers: The Usefulness of Electronic Weak Ties for Technical Advice. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, J.R.; Zmud, R.W. Channel expansion theory and the experiential nature of media richness perceptions. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. Managing user trust in B2C e-services. E-Serv. J. 2003, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.J.; Andrew, W. Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 4, 967–985. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuter, U.; Golbeck, J. Sunny: A new algorithm for trust inference in social networks using probabilistic confidence models. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–26 July 2007; pp. 1377–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Frenzen, J.; Nakamoto, K. Structure, cooperation, and the flow of market information. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 20, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; De-Juan-Vigaray, M.D. Social commerce: Is interpersonal trust formation similar between U.S.A. and Spain? J. Retail Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Chinese college students’ source selection and use in searching for health-related information online. Inform. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungenberg, E.; Lei, O.; Gray, D. Measuring the information search behaviors of adventure sport tourists. Event Manag. 2018, 23, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Suzuki, A. Motivation for information exchange in a virtual community of practice: Evidence from a Facebook group for shrimp farmers. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Hippel, E.V. How open source software works: “free” user-to-user assistance. Res. Policy 2000, 32, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, N. The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-Retailer Relationships; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 74, pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wasko, M.L.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. Mis. Quart. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Barclay, D.W. The effects of organizational differences and trust of the effectiveness of selling partner relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 12, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–720. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Peng, D.; Xie, F. A study on the Effects of TAM/TPB-based Perceived Risk Cognition on User’s Trust and Behavior Taking Yu’ebao, a value-added Payment Product, as an Example. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.D. In search of underlying dimensions: The use (and abuse) of factor analysis in personality and social psychology bulletin. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1629–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congjie, Y.; Qiaoling, D. Research on the influence of WeChat characteristics of enterprise recruitment on employer at-tractiveness based on TAM. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.Z.; Zhao, G.X.; Liu, J.P. Common method deviation in evaluation. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a Reanalysis of past research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Pan, F.M.; Zhu, J.M.; Fan, Y.G.; Yang, L.S.; Chen, D.J.; Wang, M.R.; Fan, D.Z.; Ding, N.; Wang, M.F.; et al. SPSS Statistical Analysis, 1st ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 334–344. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Xue, L.Y. Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. Mis. Quart. 2007, 31, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, R.A. A meta-analysis of cronbach’s coefficient alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2010; p. 816. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 2, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Zhu, X. Empirical study on influencing factors of Yu’e Bao use-intention based on TAM/TPB and perceived risk. Mod. Intell. 2015, 35, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Comm. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reichheld, F.F.; Schefter, P. E-loyalty: Your secret weapon on the web. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Net Information Office Website. CNNIC Released the 48th “Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development”. Available online: http://www.cnnic.cn/gywm/xwzx/rdxw/20172017_7084/202109/t20210923_71551.htm (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Agarwal, N.; Liu, H.; Lei, T.; Yu, P.S. Identifying the influential bloggers in a community. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), Palo Alto, CA, USA, 11–12 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Ye, S. Research on the influence evaluation index system of microblog opinion leaders -from the perspective of media influence. Intell. Mag. 2014, 33, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, R.; Kinshuk. An improved mix framework for opinion leader identification in online learning communities. Knowl. Based Syst. 2013, 43, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chen, Y. Research on the measurement model of user innovation value in virtual community-taking automobile forum as an example. Shanghai Manag. Sci. 2017, 39, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Song, Y. Research on behavioral motivation and influencing factors of knowledge exchange in virtual community. J. Commun. 2007, 14, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inform. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange theory perspective. Inform. Manag. 2016, 53, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Tang, X. Research on social media information forwarding based on Elm theory. Inf. Sci. 2017, 35, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Eigenvalue | Extracting the Sum of Load Squares | Rotating the Sum of Load Squares | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Total | Percentage Variance | Accumulation% | Total | Percentage Variance | Accumulation% | Total | Percentage Variance | Accumulation% |

| 1 | 8.348 | 49.108 | 49.108 | 8.348 | 49.108 | 49.108 | 4.336 | 25.509 | 25.509 |

| 2 | 2.615 | 15.383 | 64.491 | 2.615 | 15.383 | 64.491 | 3.504 | 20.613 | 46.121 |

| 3 | 1.969 | 11.580 | 76.071 | 1.969 | 11.580 | 76.071 | 3.370 | 19.822 | 65.943 |

| 4 | 1.450 | 8.527 | 84.598 | 1.450 | 8.527 | 84.598 | 3.171 | 18.655 | 84.598 |

| Item | Factor 1 | Common Factor Variance (Common Degree) | Item | Factor 2 | Common Factor Variance (Common Degree) | Item | Factor 3 | Common Factor Variance (Common Degree) | Item | Factor 4 | Common Factor Variance (Common Degree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.899 | 0.872 | R1 | 0.899 | 0.868 | BI1 | 0.858 | 0.824 | P1 | 0.752 | 0.710 |

| A2 | 0.786 | 0.718 | R2 | 0.822 | 0.775 | BI2 | 0.755 | 0.758 | P2 | 0.854 | 0.846 |

| A3 | 0.827 | 0.801 | R3 | 0.827 | 0.769 | BI3 | 0.814 | 0.808 | P3 | 0.781 | 0.712 |

| A4 | 0.900 | 0.866 | R4 | 0.854 | 0.867 | BI4 | 0.923 | 0.911 | P4 | 0.923 | 0.906 |

| A5 | 0.883 | 0.852 |

| Dimension | Item | Standard Loading | AVE | C.R. | CITC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability | A1 | 0.941 | 0.758 | 0.940 | 0.886 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.942 | A2 | 0.740 | 0.761 | ||

| A3 | 0.893 | 0.837 | |||

| A4 | 0.901 | 0.877 | |||

| A5 | 0.864 | 0.870 | |||

| Integrity/benevolence | BI1 | 0.872 | 0.747 | 0.922 | 0.827 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.916 | BI2 | 0.783 | 0.733 | ||

| BI3 | 0.857 | 0.802 | |||

| BI4 | 0.938 | 0.889 | |||

| Reputation | R1 | 0.918 | 0.749 | 0.922 | 0.868 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.924 | R2 | 0.819 | 0.788 | ||

| R3 | 0.818 | 0.772 | |||

| R4 | 0.901 | 0.866 | |||

| Predictability | P1 | 0.971 | 0.713 | 0.907 | 0.731 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.906 | P2 | 0.733 | 0.846 | ||

| P3 | 0.914 | 0.707 | |||

| P4 | 0.731 | 0.900 | |||

| Interpersonal trust | T1 | 0.731 | 0.528 | 0.816 | 0.909 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.947 | T2 | 0.764 | 0.861 | ||

| T3 | 0.792 | 0.849 | |||

| T4 | 0.606 | 0.876 | |||

| Information dissemination | ID1 | 0.873 | 0.830 | 0.951 | 0.763 |

| Cronbach’s α = 0.876 | ID2 | 0.917 | 0.721 | ||

| ID3 | 0.926 | 0.712 | |||

| ID4 | 0.928 | 0.749 |

| Ability | Integrity/Benevolence | Reputation | Predictability | Interpersonal Trust | Information Dissemination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability | 0.871 | |||||

| Integrity/benevolence | 0.442 ** | 0.864 | ||||

| Reputation | 0.383 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.865 | |||

| Predictability | 0.431 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.844 | ||

| Interpersonal trust | 0.552 ** | 0.616 ** | 0.623 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.727 | |

| Information dissemination | 0.400 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.279 * | 0.321 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.911 |

| Fit Index | χ2 | df | χ2/df | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | NNFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended range | N/A | N/A | ≤5 | ≥0.8 | ≥0.8 | ≤0.08 | ≥0.9 | ≥0.9 |

| Model value | 259.811 | 246 | 1.056 | 0.883 | 0.816 | 0.037 | 0.983 | 0.986 |

| Hypothesis | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| The link between interpersonal trust and information dissemination behaviors in the virtual community | ||

| H1 | The participants’ interpersonal trust in the virtual community is positively related to their inclinations toward information dissemination behaviors. | Supported |

| MIn-TWFB and interpersonal trust in the virtual community | ||

| H2a | The ability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the participants’ interpersonal trust in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H2b | The integrity/benevolence component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the participants’ interpersonal trust in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H2c | The reputation component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the participants’ interpersonal trust in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H2d | The predictability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the participants’ interpersonal trust in the virtual community. | Supported |

| Trust-supporting components of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community | ||

| H3a | The ability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the integrity/benevolence component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H3b | The ability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the reputation component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H3c | The integrity/benevolence component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the reputation component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H3d | The reputation component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the predictability component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H3e | The predictability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the ability component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

| H3f | The predictability component of MIn-TWFB is positively related to the integrity/benevolence component of MIn-TWFB in the virtual community. | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, T.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z. The Influence of Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance on the Information Dissemination Mechanism in Virtual Community. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106122

Zhao T, Lin J, Zhang Z. The Influence of Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance on the Information Dissemination Mechanism in Virtual Community. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106122

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Tingting, Jie Lin, and Zhenyu Zhang. 2022. "The Influence of Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance on the Information Dissemination Mechanism in Virtual Community" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106122

APA StyleZhao, T., Lin, J., & Zhang, Z. (2022). The Influence of Multi-Variation In-Trust Web Feature Behavior Performance on the Information Dissemination Mechanism in Virtual Community. Sustainability, 14(10), 6122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106122