Approach and Success in the Management of Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs): Application to Two Case Studies, the UNMISS and MONUSCO Missions of the UN

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. UN Peacekeeping Missions

- “First-generation missions” are in accordance with Chapter VI on the peaceful settlement of disputes, in which their principal and almost sole task is to interpose between countries in conflict (interstate conflicts), such as those in the Middle East, Kashmir, and Cyprus [25]. With these first missions, the intention is to help eliminate hostilities, to verify that there is no fighting, and to ensure that conflicts are not restarted. These are missions that seek to promote military security, in the hope that negotiations can settle the political conflict that triggered the hostilities. The main characteristics of these missions are the consent of the belligerents, neutrality and impartiality, and the use of force only in self-defence [26].

- “Second-generation missions” mean not only security but also peacekeeping missions. Moreover, no longer are peace missions only sent to interstate conflicts (UNIMOG, observation mission in the Iran-Iraq conflict; UNGOMAP, good offices mission in Afghanistan and Pakistan) but they are also sent to intrastate conflicts (UNTAG to assist in the transition process in Namibia; UNTAC in Cambodia) [27]. In 1992, the UN proposed a new way of viewing peace missions through its report “a program for peace” [28], which eliminated the consent of the parties and divided the action of the missions into a civilian component with humanitarian aid and reconstruction tasks, and the military component, equipped to deter actions against the population and ensure the arrival of humanitarian aid.

- “Third-generation missions” are based on Chapter VII of the founding charter of the UN with a strong coercive character. This type of mission is complex and multidisciplinary, with division in terms of its implementation, by the components of the security council, and have failed as confirmed in the UNAMIR mission (Rwanda, 1994) and UNPROFOR (Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1995).

- “Fourth-generation missions” are missions of great capacity for the adaptation and integration of multiple elements. At the end of the 1990s, as a result of deep reflection, the UN established the new peace missions through the “Brahimi Report” [29] and the “Capstone Doctrine” [30]. These missions were to be carried out with the following conditions: need for consent from the parties; impartiality, not neutrality; and the non-use of force, except in self-defence. Furthermore, interesting integration-oriented aspects were also considered: security cooperation in the theatre of operations; the exchange of information; joint analysis of the situation; improved operational control in missions; integrated security systems, and integrated mission planning.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Project Management Approach

- Iterative projects.These projects aim to improve the result by making prototypes or tests of the elements to be delivered later. Each iteration produces feedback that is presented to stakeholders, thereby enabling them to change their opinions and it also provides new knowledge for the work team.

- Incremental projects.The objective of these projects is to prioritise speed in the delivery of value to stakeholders, and the faster and greater the value, the better. With rapid delivery, the stakeholders can propose changes in a later phase, and the team can also quickly observe the changes, risks, and knowledge acquired.

3.2. Management of Complex Projects

- In a complex project, the interpersonal and leadership skills of team members and their director are at the same level or sometimes higher than their technical knowledge. These skills should detect changes before they take effect.

- Leadership should make it easier to take immediate measures to prevent negative events (threats) and to favour positive events (opportunities).

- The stakeholders should be part of the social network of the project.

- The essential units to be executed should be continuously evaluated in such a way that they can be immediately changed to respond to these changes.

3.3. Success in PKO Projects

4. Methodology

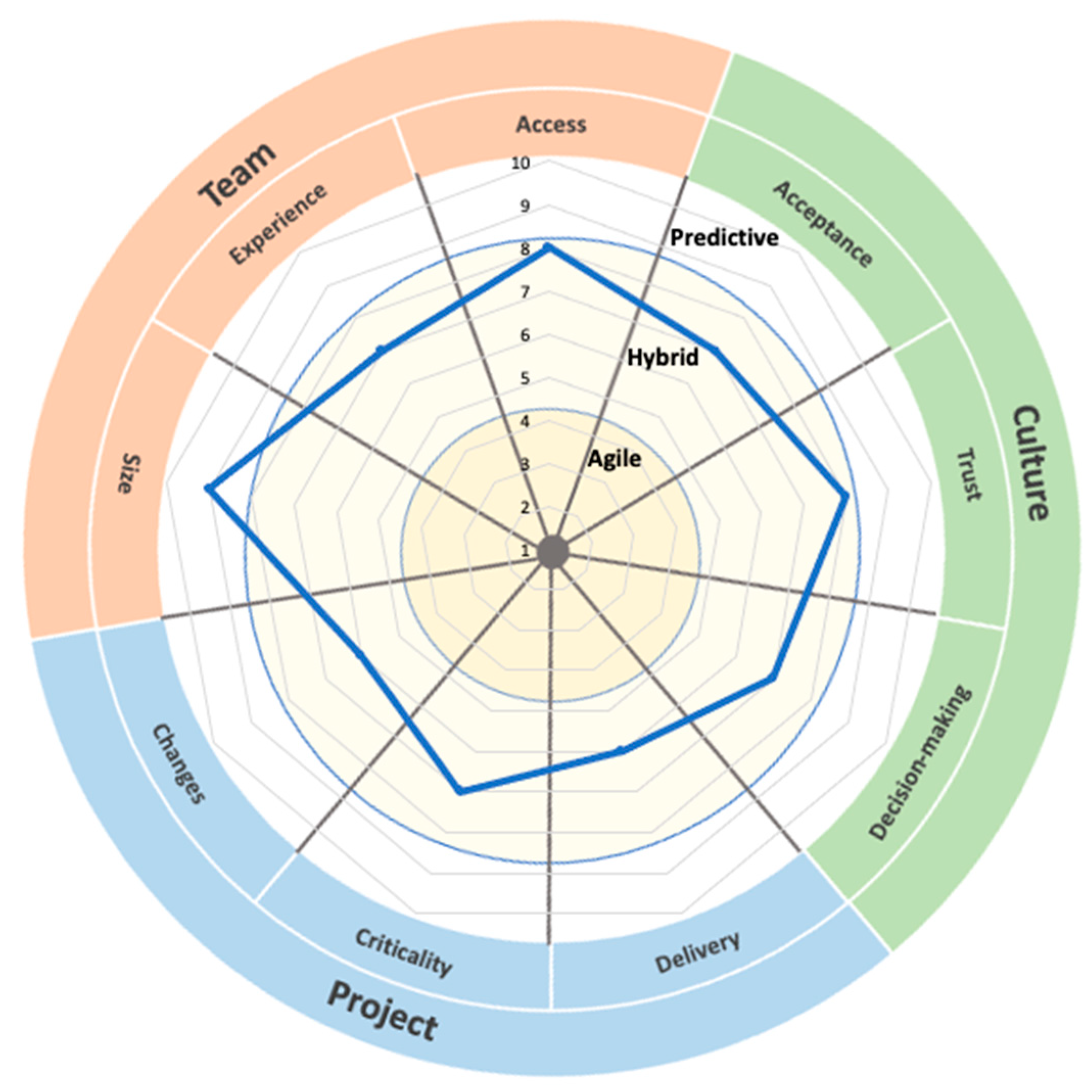

4.1. Determining the Project Approach of a PKO

- Culture.

- Buy-in to approach. Is there support within the organisation that is going to carry out the project to carry out an Agile approach? (YES = 1/PARTIAL = 5/NO = 10).

- Trust in the team. Is there confidence within the organisation that the team will perform well in the Agile approach, with the support of the organisation? (YES = 1/PROBABLY = 5/NO = 10).

- Decision-making powers of the team. Will the team be given the autonomy to make their own local decisions about whether to undertake work? (YES = 1/PROBABLY = 5/NO = 10).

- Project.

- Likelihood of change. What percentage of requirements is likely to change or be discovered on a monthly? (HIGH = 1/MEDIUM LEVEL = 5/LOW = 10).

- Criticality of product or service. How important is it for stakeholders that the project fails? (CRITICAL = 1/IMPORTANT = 5/UNIMPORTANT = 10).

- Incremental delivery. Should the project be delivered piece-by-piece and quickly? (YES = 1/SOMETIMES = 5/NO = 10).

- Team.

- Team size. What is the size of the core team? (1–9 = 1/10–20 = 2/21–30 = 3/31–45 = 4/46–60 = 5/61–80 = 6/81–110 = 7/111–150 = 8/151–200 = 9/201+ = 10).

- Experience levels. Are the main project team members experts in uncertainty environment, change management, and crisis management? (YES = 1/PARTIALLY = 5/NO = 10).

- Access to stakeholders. Does the main project team have open access to stakeholders? (YES = 1/PARTIAL = 5/NO = 10).

4.2. Measurement of the Success of a PKO

- Primacy of politics and organisation of elections.

- Protection and stabilisation.

- Local and international ownership.

- Regional and international support.

- Consistency and participation.

- Legitimacy, impartiality, and credibility.

- Women, peace, and security.

- People-centred approach.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. South Sudan

5.1.1. Background

5.1.2. What Is the Focus of PKO UNMISS?

- Culture:

- Buy-in to approach: This mission originates from a previous, more versatile mission, UNMIS. The current mission adopts the protection of civilians as its primary objective. Its integrated approach presents predictable and Agile aspects simultaneously (Value: 5).

- Trust in the team: Team members carry out highly decentralised work but need authorisation from the mission representative. Non-total confidence (Value: 6).

- Decision-making powers of the team: Civil/military duality. The actions of the civilian team possess no autonomy and depend on the military component (Value: 4).

- Project (PKO):

- Probability of change: There is a significant probability of change in the mission (Value: 3).

- Criticality of product or service: Critical since it contains a highly significant component of violence against civilians. This constitutes the priority objective (Value: 2).

- Incremental delivery: No immediate termination of the mission is expected (Value: 9).

- Team:

- Team size: Management team comprises an average of 80–100 people with decision-making capacity. The documentation indicates more than 400 people. The organisation chart shows higher levels (Value: 6).

- Experience levels: With strong decentralisation, 10 offices, and new integrated Agile tools from CPAS, their experience is extensive (Value: 6).

- Access to stakeholders: They have access to local and regional leaders and can hold meetings on issues that may affect the improvement of quality of life (Value: 9).

5.1.3. Has the UNMISS PKO Been Successful?

5.2. Democratic Republic of the Congo

5.2.1. Background

5.2.2. What Is the Focus of the MONUSCO PKO?

- Culture:

- Buy-in to approach: This mission began in 2010 and it is unlikely that its conception was intended to have an Agile approach (Value: 7).

- Trust in the team: The team applies the integral mission as a sequential set of activities with certain feedback (Value: 8).

- Decision-making powers of the team: Strong mission hierarchy and submission of the civilian component to the military (Value: 7).

- Project (PKO):

- Probability of change: No major changes are expected (Value: 6).

- Criticality of product or service: Not critical. No change (Value: 7).

- Delivery: If suitable conditions are put in place in the governance and control of the eastern part, the mission may end within the next 12 months (Value: 6).

- Team:

- Team size: From the documentation consulted, there are more than 200 people in the team for the mission (Value: 9).

- Experience levels: Great centralisation, with no autonomy in the headquarters of the mission (Value: 7).

- Access to stakeholders: According to the data, the team does not have guaranteed access to all or a large part of the stakeholders (Value: 8).

5.2.3. Has the MONUSCO PKO Been Successful?

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Project Management Institute (PMI). Guía de los Fundamentos para la Dirección de Proyectos, 6th ed.; Guía PMBOK (Project Management Institute Inc.): Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, B.F. Committing to Peace. The Successful Settlement of Civil Wars; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fortna, V.P. Does Peacekeeping Work? Shaping Belligerents’Choices After Civil War; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, M.W.; Sambanis, N. International Peacebuilding: A Theoretical and Quantitative Analysis. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, A.; Gizelis, T.I.; Dorussen, H. Managing mistrut: An analysis of cooperation with UN peacekeeping in Africa. J. Confl. Resolut. 2013, 57, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, M.J.; Sergenti, E.J. Do UN interventions cause peace? Using matching to improve causal inference. Q. J. Political Sci. 2008, 3, 89–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NN.UU. Creación de Una Nueva Operación. Naciones Unidas Mantenimiento de la paz. Departamento de Operaciones de Paz. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/es/forming-new-operation (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Arellano, D.; Danti, J.; Pérez, M.F. Proyectos y Sistemas Complejos. PMI Project Management Institute Madrid. 2016. Available online: https://pmi-mad.org/socios/articulos-direccion-proyectos/1225-proyectos-y-sistemas-complejos (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Brady, T.; Davies, A. Managing structural and dynamic complexity: A tale of two projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varajão, J. Success Management as a PM Knowledge Area—Work-in-Progress. Procedia Comp. Sci. 2016, 100, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surco-Gillen, Y.C.; Romero, J.; Rodríguez-Rivero, R.; Ortiz-Marcos, I. Success Factors in Management of Development Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Rekveldt, M.; Bakker, H.; Hertogh, M. Comparing project complexity across different industry sectors. Complexity 2018, 2018, 3246508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Assessing and moving on from the dominant project management discourse in the light of project overruns. IEEE Transact. Eng. Manag. 2005, 52, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J. International Construction Project Management: General Theory and Practice; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, V.; Rapaport, B.; Omarova, A. Addressing wicked problems in a range of project types. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 12, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.; Ahn, J.; Shane, J.; Strong, J.; Gransberg, K.C. Defning Complex Project Management of Large U.S. Transp. Proj. 2012, 17, 170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; Chan, A.P.C. Measuring complexity for building projects: A Delphi study. Eng. Cons. Architec. Manag. 2012, 19, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Kumar, B.; Tomson, A. Complexity measurement of a project activity. Int. J. Ind. Sys. Eng. 2011, 8, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Bautista, R.; Diego-Mas, J.A.; León-Medina, D. Measuring the Project management complexity: The case of information technology projects. Complexity 2018, 2018, 6058480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordova, S.; Zwilling, M.; Rozen, O. The impact of the management method on IT Project success. Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2021, 29, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dielh, P.F.; Druckman, D. Multiple peacekeeping missions: Analysing interdependence. Int. Peacekeeping 2018, 25, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkina, D.B. Successes and failures of United Nations Peace Operations. Vestn. St. Petersburg Univ. Hist. 2020, 65, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, T.; Solá-Martín, A. The United Nations, Armed Conflict and Peacekeeping. Handbook of Defence Politics; Open University of Catalonia: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- NN.UU. Carta de las Naciones Unidas. Carta de San Francisco. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/charter-united-nations/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Añaños Meza, C.M. La consolidación de la paz en el derecho internacional. REEI 2010, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vega Fernández, E. Operaciones Militares de Gestión de Crisis, Tipos, Evolución y Características, 1st ed.; Instituto Universitario General Gutiérrez Mellado-UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona llorens, J. El Mantenimiento de la Paz y la Seguridad Internacionales, 14th ed.; Vallejo, M.D., Ed.; Las Organizaciones internacionales; Editorial Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2006; p. 884. [Google Scholar]

- Boutros-Ghali, B. Un Programa de paz: Diplomacia Preventiva, Establecimiento de la paz y Mantenimiento de la paz; A/47/277; Asamblea General Consejo de Seguridad; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi, L. Informe Brahimi (A/55/305-S). In Asamblea General Consejo de Seguridad; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado Arroyo, F. El futuro de las operaciones de paz de la ONU. IEEE 2013, 43, 13. [Google Scholar]

- DPKO. DFS. A New Horizon Initiative: Progress Report No 1. 2010. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/newhorizon_update01_0.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- De Coning, C. Adaptive peacebuilding. Int. Aff. 2018, 94, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DPO. A4P: Nuestros Objetivos Principales para el Mantenimiento de la Paz. ONU. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/A4P/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Johns, T.G. The Art of Project Management and Complexity. In Proceedings of the PMI Global Congress, Denver, CO, USA, 19 October 2008; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/art-decentralized-project-teams-6934 (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Murray, P.; Thomas, S. Designing Complex Projects. In Proceedings of the PMI Global Congress, Denver, CO, USA, 19 October 2008; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/designing-complex-projects-6951 (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Vega Mancera, J.A. Inteligencia militar en las operaciones de naciones unidas. Soluciones adaptadas para lograr el éxito. Ejercito 2012, 859, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute (PMI). Guía Práctica de Ágil, 1st ed.; Project Management Institute, Ed.; Project Management Institute Inc.: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ONU_PKO. Proyectos de Efecto Rápido para Comunidades. Mantenimiento de la Paz. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/es/quick-impact-projects-communities (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- ONU_CPAS. Infographic—Agile Methodology. Flexible Approaches to Developing e-Services. UNDP in Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.uz.undp.org/content/uzbekistan/en/home/media/infographics/infographic---agile-methodology--flexible-approaches-to-developi.html (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Wolf Project. Gestión Híbrida de Proyectos: El Trompagardo—YouTube. Wolf Project. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2nZrQPYZzc (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Blanchard, B.S. Ingeniería de Sistemas, 1st ed.; ISDEFE: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Torrón Durán, R. El Análisis de Sistemas, 1st ed.; ISDEFE: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rihani, S. Complex Systems: Theory and Development Practice. In Futures, 1st ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, P. A Simple View of ‘Complexity’ in Project Management; Mosaic, A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature; Mosaic Project Services Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, P.F. International Peacekeeping; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. Military Operational Measures of Effectiveness for Peacekeeping Operations; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkina, D. A recipe for success? Ingredients of a successful peacekeeping mission. Int. Peacekeeping 2006, 13, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigri, U.; Başar, U. An analysis of assessment of peacekeeping operations. Korean J. Def. Anal. 2014, 26, 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Wistuba, F.W. Preconditions for Success in UN Peacekeeping Operations Table of Content (Issue July); Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M. Measuring the Success of Peace Operations: Directions in Academic Literature. NUPI Work. Pap. 2016, 862, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bardalai, A.K. A conceptual framework for assessing traditional peace operations. Inst. Def. Stud. Anal. 2019, 13, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, P.F.; Druckman, D. Evaluating peace operations. Political Sci. 2010, 2010, 153587162. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Brûlé, S. Evaluating Peacekeeping Missions: A Typology of Success and Failure in International Interventions; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lijn, J.; Smit, T. Peace Operations and Conflict Management. In SIPRI Yearbook 2018: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 101–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bratt, D. Assessing the success of UN peacekeeping operations. Int. Peacekeeping 1996, 3, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, D. Peace over justice: Developing a framework for UN peacekeeping operations in internal conflicts. Glob. Gov. 1999, 5, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NUPI Forside—Forside. NUPI. Available online: https://www.nupi.no/nupi/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- De Freitas, M.D.; De Araujo, F.C.C. Comparative analysis of project management methodologies Pmbok and Agile—A case of study with companies of the Brazilian energetic sector. Rev. Geintec Gest. Inov. Tecnol. 2019, 9, 4993–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P.; Tick, J. Suitability of PMBok 6th Edition for Agile-Developed IT Projects. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics (INCI), Budapest, Hungary, 21–22 November 2018; pp. 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- De Coning, C.; Brusset, E. Towards a Comprehensive Results-Based Reporting and Performance Assessment Framework: For UN Peacekeeping Operations; NUPI: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Menkhaus, K. Making Sense of Resilience in Peacebuilding Contexts: Approaches, Applications, Implications. Geneva Peacebuilding Platform 2013, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.F. South Sudan the Untold Story from Independence to Civil War, 1st ed.; I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lijn, J. Success and failure of un peacekeeping operations: UNMIS in Sudan. J. Int. Peacekeeping 2010, 14, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambakari, C.; Kang, T.K.; Sanders, R.A. The Role of the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) in Protecting Civilians. The Challenge of Governance in South Sudan; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.; Verma, P.; Valdmanis, V. Evaluation of the Contribution of the UNMISS Civil Affairs Division to the Reduction of Local Conflict in South Sudan; Issue April; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A.; Hunt, C.; Yin, H.; Kumalo, L. Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS); Norwegian Institute of International Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Peace Institute (IPI). Prioritization and Sequencing of Security Council Mandates: The Case of UNMISS; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ONU_UNMISS. UNMISS. Naciones Unidas Mantenimiento de la paz. Naciones Unidas. Mantenimiento de La Paz. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/es/mission/unmiss (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Reynaert, J. MONUC/MONUSCO and Civilian Protection in the Kivus; International Peace Information Service: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2011; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- ONU_UNDP. Building Peace and Advancing Development in the Great Lakes Region; ONU: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malan, M.; Boshoff, H. A 90-day plan to bring peace to the DRC? An analysis of the Pretoria Agreement of Mark Malan and Henri Boshoff. Instit. Secur. Stud. 2002, 61, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Bayo, O.A. The Factors Behind Successes and Failures of United Nations Peacekeeping Missions: A Case of the Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Altern. Perspect. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 914–932. [Google Scholar]

- ONU_MONUSCO. MONUSCO. Naciones Unidas Mantenimiento de la paz. Naciones Unidas. Mantenimiento de La Paz. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/es/mission/monusco (accessed on 11 September 2020).

| Dimension | Success? | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Primacy of politics and organisation of elections | NO | Its main mandate involved the implementation of governance and the holding of elections. This proved impossible to carry out due to erroneous analysis and the fact that no reflection was provided of the greater possibility of a civil war in South Sudan. |

| Protection and stabilisation | YES | UNMISS protection zones were established to protect more than 200,000 people. Killings were reduced to sporadic episodes only. |

| Local and international ownership | YES | Management of the mandate was distributed across 10 offices in the country, which provided closeness to the population and their problems. |

| Regional and international support | NO | Growing disinterest in international and regional actors for the stabilisation of the country. |

| Coherence and participations | NO | Although the mission remains consistent with the mandate received, it still supports governance and governance that limits the rights of its nationals and the members of the mission themselves. |

| Legitimacy, impartiality, and credibility | NO | Although the level of violence has decreased and credibility has increased, no supporting inter-tribal community talks to reduce tension are being reflected in the political and social situation. There is a lack of direct communication with the population. There is no legal certainty for nationals. |

| Women, peace, and security | NO | The numerous sexual abuses committed against women, including in the camps managed by UNMISS, have not been halted by a general action. The lack of governance has eliminated the possibility of prosecution for these acts. |

| People-centred approach | NO | UNMISS focuses on a “fact-based approach” under strategic guidelines: this has failed to affect the population at ground level. |

| Dimension | Success? | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Primacy of politics and organisation of elections | YES | Its main mandate involved the implementation of governance and the holding of elections. This is endorsed by the numerous elections held and the establishment of governance. |

| Protection and stabilisation | YES | The signing of numerous intranational and regional agreements with violent groups has diminished the stability of the whole country, with precariousness remaining in Goma, in the eastern part of the country. |

| Local and international ownership | NO | The reforms proposed by the mission in the protection of nationals and their rights have been curtailed by the action of the government and its militias. |

| Regional and international support | YES | Stabilisation of the country is increased with the signing of agreements with neighbouring countries. |

| Coherence and participations | NO | The low effectiveness in the mission staff’s relationships with Congolese civil society is further encouraged by their government. There is little participation in social and cultural actions. |

| Legitimacy, impartiality, and credibility | YES | The mission’s actions in controlling Ebola, the decrease in violence despite the lack of collaboration by the Congolese government, the stabilisation of the eastern zone, and the creation of security zones have lent legitimacy and credibility to the mission in the eyes of the population. |

| Women, peace, and security | YES | The mission has succeeded in promoting women within Congolese society, as well as in encouraging campaigns to prevent sexual abuse. Integration of NGOs into the mission has been fundamental in improving the safety of women. |

| People-centred approach | NO | The civil aspect of the mission in terms of approaching the population from a social point of view has not been accompanied by the development of society in general. There is a lack of means focusing the mission more on stabilization. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarez-Espada, J.M.; Fuentes-Bargues, J.L.; González-Gaya, C. Approach and Success in the Management of Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs): Application to Two Case Studies, the UNMISS and MONUSCO Missions of the UN. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106097

Alvarez-Espada JM, Fuentes-Bargues JL, González-Gaya C. Approach and Success in the Management of Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs): Application to Two Case Studies, the UNMISS and MONUSCO Missions of the UN. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106097

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez-Espada, Juan Manuel, José Luis Fuentes-Bargues, and Cristina González-Gaya. 2022. "Approach and Success in the Management of Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs): Application to Two Case Studies, the UNMISS and MONUSCO Missions of the UN" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106097

APA StyleAlvarez-Espada, J. M., Fuentes-Bargues, J. L., & González-Gaya, C. (2022). Approach and Success in the Management of Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs): Application to Two Case Studies, the UNMISS and MONUSCO Missions of the UN. Sustainability, 14(10), 6097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106097