Abstract

Compassion fatigue is a unique form of burnout that can seriously negatively impact both teachers’ development and students’ growth. A questionnaire survey was carried out among 1558 primary and secondary school teachers from 28 provincial administrative regions by using the Professional Quality of Life Scale (Pro QOL-5), and the results showed that: (1) the quality of professional life of primary and secondary school teachers in China is at the medium level, and compassion fatigue above the mild level is widespread; (2) there are individual differences in teachers’ compassion satisfaction and burnout. Teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience at the senior title or above and college degree or below have higher levels of compassion satisfaction and lower levels of burnout. The level of compassion satisfaction is relatively high among teachers who are at school-level leadership or above and who are primary school teachers. The level of secondary trauma is relatively high among teachers in secondary schools and secondary vocational schools; (3) position (headteacher and class teachers), title (primary), and school type (secondary) have a significant influence on the degree of compassion fatigue. The findings suggest that compassion fatigue among primary and secondary school teachers needs urgent attention. By helping teachers identify compassion fatigue, learn self-care, adjust self-cognition, and clarify the boundaries of their professional competence, teachers’ compassion fatigue can be prevented and alleviated.

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, the study of sustainable development strategies has become a common theme in social development research around the world. The sustainable development of society as a whole depends on the sustainable development of its basic cells, the individuals. The sustainable development of individuals cannot be achieved without education, and teachers play a fundamental and critical role in promoting sustainable human development. Across the globe, a growing number of countries are embarking on dramatic educational reforms that are expected to transform the current educational landscape and help students develop the knowledge, skills, and values needed for sustainable development.

Current educational reforms are more sensitive to the needs of learners than traditional ones and require teachers to adapt their teaching styles to meet those needs [1]. However, this requires teachers to have the resources and autonomy to meet the individual needs of their students, yet the lag in grassroots school management reforms has prevented teachers from practicing these reforms, including the deprivation of teachers’ technical freedom to teach (deprivation of power over labor control) and the deprivation of educational cognition (deprivation of power to determine the pedagogical value of teachers’ work). In addition, the arbitrary distribution of school work, the lack of teacher autonomy over their work, poor student quality, lack of parental support, and inadequate teacher training have led to high levels of stress in broad educational reforms, with some negative consequences for teachers [2]. When too many reforms are implemented too quickly, reforms can negatively affect the emotional well-being of educators [3]. A large Canadian survey revealed that 62% of teachers felt stress related to having to deal with student health and personal issues as educational reform moved forward, and since compassion fatigue can develop through the stress of wanting but not being able to help someone in distress [4], this may imply that educators may be more susceptible to compassion fatigue during the fast-paced educational reform process.

1.1. What Is Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue is a relatively new concept in the field of psychology. It first appeared in the report on nurse burnout [5] and is regarded as a unique form of burnout. Figley (1995) defines compassion fatigue as “the behaviors and emotions that naturally arise from empathizing with a significant traumatic event during help, which results from the stress of wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person [6].“ As with any other type of fatigue, compassion fatigue reduces the ability or interest of helpers in bearing the pain of others, so it is often used to describe “the cost of caring.” It should be emphasized that compassion fatigue is not a pathological reaction but a “natural, predictable, treatable and preventable” response to a traumatic individual.

Compassion fatigue is considered to be the result of working directly with victims of disasters, trauma, or illness, especially in the healthcare industry [7]. Individuals working in other helping professions are also at risk for experiencing compassion fatigue [4]. These include child protection workers, veterinarians [8], and teachers [6]. Teachers, as with medical workers, firefighters, police, social workers, and other personnel, are working to help others. Teachers are exposed to pressure sources for a long time in their work practice. They have to deal with various educational and teaching problems, establish and maintain a good relationship between teachers and students, and take the initiative to give more care and help to students, so they are prone to compassion fatigue.

1.2. The Clinical Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue

People who experience compassion fatigue may exhibit a variety of symptoms including lowered concentration, numbness or feelings of helplessness, irritability, lack of self-satisfaction, withdrawal, aches and pains, or work absenteeism. The clinical symptoms of compassion fatigue are similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, secondary trauma, vicarious (indirect) traumatization, burnout, etc. In order to better recognize and understand the concept of compassion fatigue, Sun et al. (2011) compared and analyzed the relationship between these concepts and concluded that the essence of compassion fatigue is mainly manifested as follows: First, the clinical symptoms of helping people are similar to post-traumatic stress disorder [9]. They are not due to the traumatic event, but a prolonged contact with the traumatized person. Second, the root cause of compassion fatigue in the helping group lies in the active payment of empathy and other large amounts of psychological energy during the rescue process and thus encounters empathic stress [10]. This study holds that teachers’ compassion fatigue is based on the premise that they actively give empathy to the real, implicit, or imaginary relief targets (students). In the process of providing material or emotional assistance to the relief targets (students), they suffer secondary trauma, which reduces their ability and interest in empathizing with the relief targets (students), the academic work burnout feeling emerges, and even changes in their original values and worldview occur, along with a series of physical and mental discomfort symptoms.

1.3. The Risk Factors of Compassion Fatigue

Several personal characteristics may lead to compassion fatigue. Overly conscientious individuals, perfectionists, and selfless individuals are more likely to suffer from secondary traumatic stress. Those who have low levels of social support or high levels of stress in personal life are also more likely to develop STS.

In addition, previous histories of trauma that led to negative coping skills, such as bottling up or avoiding emotions and having small support systems, increase the risk for developing STS [11]. Workers in fields where STS is most prevalent, such as healthcare, are more likely to suffer compassion fatigue due to organizational characteristics. For example, a “culture of silence” where stressful events such as deaths in an intensive-care unit are not discussed after the event is linked to compassion fatigue [12]. It may also be responsible for high rates of STS if people are not aware of symptoms and are not trained in the risks associated with high-stress jobs [13]. As the needy interact more, compassion fatigue becomes more intense. Because of this, people living in urban cities are more likely to experience compassion fatigue. People in large cities interact with more people in general, and because of this, they become desensitized toward people’s problems. Homeless people often make their way to larger cities. Ordinary people often become indifferent to homelessness when they see it regularly [14].

1.4. The Compassion Fatigue among Teachers

In response to the changing landscape of post-secondary institutions, sometimes as a result of having a more diverse and marginalized student population, both campus services and the roles of student affairs professionals have evolved. These changes are efforts to manage the increases in traumatic events and crises [15]. Due to the exposure to student crises and traumatic events, student affairs professionals, as front-line workers, are at risk for developing compassion fatigue. Such crises may include sexual violence, suicidal ideation, severe mental health episodes, and hate crimes/discrimination. Student affairs professionals who are more emotionally connected to the students with whom they work and who display an internal locus of control are found to be more likely to develop compassion fatigue as compared to individuals who have an external locus of control and are able to maintain boundaries between themselves and those with whom they work.

The specificity of the object, process, nature, and purpose of teachers’ work determines that teachers need to actively pay much emotion, care, and patience to students in their work. Empathy is a core professional competency of teachers [13]. Teachers with high empathy also tend to be more enthusiastic about their work and will provide more care, wisdom, passion, and quality instruction for their students. The capacity to accomplish these tasks lies in the individual teachers, but this resource may be gradually exhausted when teachers are overworked, and teachers’ compassion cannot be satisfied [16]. Expressing empathy is a regular part of teachers’ education and teaching process. If teachers devote a lot of empathy and other psychological energy to empathizing with students but fail to achieve a good empathy effect, they will quickly develop “compassion fatigue.” Teachers experiencing compassion fatigue will undergo changes in physical, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, and professional performance, such as feeling tired, numb, or distant from students, being impatient or intolerant of student matters, having poor teaching work, and having a decreased sense of responsibility [3].

1.5. Prevention of the Compassion Fatigue

1.5.1. Mindfulness

Self-awareness as a method of self-care might help to alleviate the impact of vicarious trauma (compassion fatigue). Students who took a 15-week course that emphasized stress reduction techniques and the use of mindfulness in clinical practice had significant improvements in therapeutic relationships and counseling skills [17]. The practice of mindfulness according to Buddhist tradition is to release a person from “suffering” and to also come to a state of consciousness of and relationship to other people’s suffering. Mindfulness utilizes the path to consciousness through the deliberate practice of engaging “the body, feelings, states of mind, and experiential phenomena (dharma).” The following therapeutic interventions may be used as mindfulness self-care practices: somatic therapy (body); psychotherapy (states of mind); emotion-focused therapy (feelings); Gestalt therapy (experiential phenomena) [18].

1.5.2. Self-Compassion

In order to be the best benefit for clients, practitioners must maintain a state of psychological well-being [19]. Unaddressed compassion fatigue may decrease a practitioner’s ability to effectively help their clients. Some counselors who use self-compassion as part of their self-care regime have had higher instances of psychological functioning [19]. The counselor’s use of self-compassion may lessen experiences of vicarious trauma that the counselor might experience through hearing clients’ stories. Self-compassion as a self-care method is beneficial for both clients and counselors.

1.6. The Aim of the Current Study

Compassion fatigue is a unique mental health issue that can occur after helping people by empathizing, caring, and helping others. In the helping profession, compassion fatigue as a particular kind of burnout is the price of caring. Teachers are exposed to stressors for long periods of time in their work practices, not only to deal with various educational and teaching issues, but also to establish and maintain good teacher–student relationships and take the initiative to give more care and help to students, so they are prone to the problem of compassion fatigue, which leads to inappropriate teacher behaviors and affects the professional ethics of teachers. Yet, this issue has not yet attracted attention in China. The current study, using the method of empirical research, investigates the current situation of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers in China. These are of great significance to enrich the current international research of compassion fatigue of teachers and prevent teachers’ moral anomie due to compassion fatigue.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

In the form of a web-based survey, this study used the cluster random sampling method to distribute the questionnaire and obtain responses from 1558 primary and secondary school teachers in 28 provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government of China, including Zhejiang, Hebei, Guangdong, Sichuan, Guizhou, Qinghai, and Xinjiang. Finally, 1527 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a valid return rate of 98.01%. Among the valid questionnaires collected, 831 (54.42%) were teachers in the eastern region, 696 (45.58%) were teachers in the midwestern regions; 552 (36.15%) were male teachers, 975 (63.85%) were female teachers; 572 (37.46%) were primary school teachers, 599 (39.23%) were secondary school teachers, 193 (12.64%) were ordinary high school teachers, 163 (10.67%) were secondary vocational school teachers; 192 (12.57%) teachers were in schools above the prefectural and municipal level, 434 (28.42%) were at the district and county level, 611 (40.01%) were in townships, and 290 (18.99%) were in rural areas.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. General Materials

By referring to relevant literature and combining with the characteristics of teachers, a questionnaire of teachers’ biographical information was prepared, which included items such as region, gender, teaching experience, teaching subject, title, position, education background, location of the school, and school type.

2.2.2. Professional Quality of Life Scale (Pro QOL-5)

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (Pro QOL-5) can be used to measure both positive (compassion satisfaction) and negative (compassion fatigue) aspects of compassion. Compassion fatigue is composed of two parts: burnout and secondary trauma. Burnout includes the typical symptoms of job burnout, such as frustration, anger, and depression; secondary trauma is a type of negative emotion caused by fear and work-related trauma. The entire questionnaire included 30 items divided into three sub-scales, compassion satisfaction (CS), burnout (BO), and secondary traumatic stress (STS), with ten items per sub-scale. The score was assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 5 = completely), and the five items of 1, 4, 15, 17, and 29 were reversed. The total score of each sub-scale ≤22 indicates low level; 23~41 indicates medium level, and ≥42 indicates high level. The total score of each sub-scale of risk values was: compassion satisfaction sub-scale score of 33 (25%) or below, burnout score of 26 (75%) or above, secondary trauma score of 17 (75%) or above [1].

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (Pro QOL-5) covers various types of occupations. When used to measure teachers’ compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, only the word “helpers” in the original scale needs to be replaced by “teachers” in the original scale, and these changes do not need special permission from the test developer [20]. The structural validity of ProQOL-5 is supported by over 200 peer-reviewed articles, with evidence that over 100,000 articles and half of the 100 published research papers on compassion fatigue, secondary trauma, and vicarious traumatization use ProQOL-5 or earlier versions. The internal consistency α coefficient of the scale was: 0.88 for compassion satisfaction, 0.75 for burnout, and 0.81 for secondary trauma [20]. In this study, Cronbach’s α coefficients of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma were 0.93, 0.85, and 0.81, respectively.

2.3. Procedure

In this study, a group test was conducted anonymously. Questionnaires were sent to the subjects through WeChat, QQ, Dingding, and Email with the consent of the subjects and the leaders of the unit, and the questionnaires were directly collected through the background of Wenjuanxing. SPSS25 statistical analysis software was used to measure the levels of compassion fatigue, burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction, as well as the correlation between these phenomena, and to explore the compassion fatigue of teachers with different demographic characteristics (region, gender, teaching experience, position, etc.).

3. Results

3.1. The Compassion Fatigue among Primary and Secondary School Teachers

3.1.1. The Teachers’ Scores on the Subscale of Professional Quality of Life Scale

According to the analysis of 1527 valid questionnaires (Table 1), it was found that the professional life quality of primary and secondary school teachers in China was at a medium level. The total score on the compassion satisfaction (CS) subscale was (36.23 ± 7.66), the number of people in the low-level group was 70 (4.58%), and the number of people in the medium- and high-level groups was 1457 (95.42%); the total score of the burnout (BO) subscale was (24.33 ± 6.58), and the number of people in the medium- to the high-level group was 932 (61.03%); the total score of secondary trauma (STS) was (25.37 ± 6.28), and the number of people in the medium- to the high-level group was 999 (65.42%). According to the above analysis, it can be found that Chinese primary and secondary school teachers’ compassion satisfaction was at medium and high levels, while burnout and secondary trauma were at a medium level.

Table 1.

Professional Quality of Life Scale subscale scores of primary and secondary school teachers and the number of people in each level group (N = 1527).

3.1.2. The Level of Compassion Fatigue among Teachers

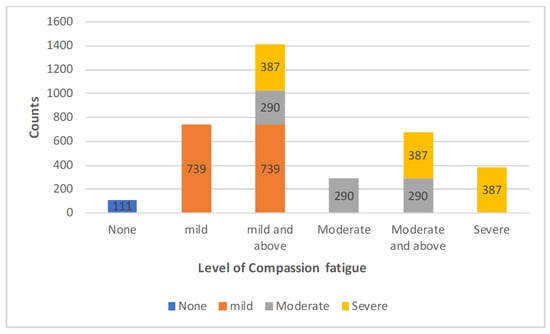

According to the judgment criteria of mild, moderate, and severe compassion fatigue in the user manual of the occupational quality of life scale by Stamm (2010), if the total score of any subscale exceeds the critical value, it is mild compassion fatigue, and if the total score of any two subscales exceeds the critical value, it is moderate compassion fatigue. If the total scores of the three subscales exceed the critical value, it is severe compassion fatigue. Among the 1527 primary and secondary school teachers in this study, 111 (7.27%) had no compassion fatigue, 739 (48.40%) had mild compassion fatigue, 290 (18.99%) had moderate compassion fatigue, and 387 (25.34%) had severe compassion fatigue (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis table of compassion fatigue among primary and secondary school teachers (N = 1527).

As shown from Table 2 and the detection map of compassion fatigue for primary and secondary school teachers (Figure 1), compassion fatigue was common among primary and secondary school teachers: 1416 teachers (92.73%) showed mild compassion fatigue or above, and 677 teachers (44.34%) showed moderate compassion fatigue or above.

Figure 1.

Results of compassion fatigue detection among elementary and secondary school teachers. The level of compassion fatigue of the teachers was divided into no detection, mild, moderate and severe. The no detection level means the score of the teachers in the dimension of compassion satisfaction (CS) was higher than 33, burnout (BO) was lower than 26, and secondary traumatic stress (STS) lower than 17; the mild level means the score of the teachers in the dimension of CS was lower than 33, or BO was higher than 26, or STS higher than 17; in the moderate level means the score of the teachers in any two dimensions of professional quality of life scale was exceeds the critical value; in the severe level means the score of the teachers in the dimension of CS was lower than 33, BO was higher than 26, and STS higher than 17.

3.2. The Difference among CS, BO, and STS

Data from the questionnaires were processed by SPSS25, and independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted with the subjects’ biographical information as the independent variable and compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma as the dependent variables. It was found that there were no statistical differences in empathy satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma among primary and secondary school teachers of different gender, teaching subject, and school location. The difference between teachers’ compassion satisfaction in the eastern and western regions was marginally significant: eastern (36.57 ± 7.56) > midwestern (35.81 ± 7.77), p = 0.054; there was a statistically significant difference in the secondary trauma dimension: eastern (25.08 ± 6.41) < midwestern (25.73 ± 6.102), p = 0.044; there was no statistically significant difference in the burnout dimension. Table 3 shows the statistical differences in compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma by teaching experience, position, title, education, and school category (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Differences in the dimensions of compassion fatigue among primary and secondary school teachers (N = 1527).

3.2.1. The Impact of Teaching Experience on CS and BO

One-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences in the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma among teachers with teaching experiences of 0–3 years, 4–9 years, 10–20 years, and more. The results showed that in the dimension of compassion satisfaction, F = 10.383, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that teachers with 0–3 years of teaching experience (35.15 ± 7.01) < teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (37.66 ± 7.72), teachers with 4–9 years of teaching experience (35.57 ± 7.72) < teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (37.66 ± 7.72), teachers with 10–20 years of teaching experience (35.54 ± 7.77) < teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (37.66 ± 7.72); in the burnout dimension F = 6.240, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that teachers with 0–3 years of teaching experience (24.85 ± 6.33) > teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (23.38 ± 6.51), teachers with 4–9 years of teaching experience (25.06 ± 6.85) > teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (23.38 ± 6.51), teachers with 10–20 years of teaching experience (24.79 ± 6.57) > teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience (23.38 ± 6.51); there were no statistical differences in the secondary trauma dimension among teachers in each teaching experience (F = 2.184, p = 0.088).

3.2.2. The Impact of the Position of Teacher on CS and BO

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences among classroom teachers, headteachers, middle-level school leaders, and school-level leaders and above on the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma, and the results showed that in the compassion satisfaction dimension F = 21.475, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that class teachers (35.58 ± 7.74) < middle-level school leaders (38.80 ± 6.96), class teachers (35.58 ± 7.74) < school-level leaders and above (41.11 ± 7.15), headteachers (35.57 ± 7.39) < middle-level school leaders (38.80 ± 6.96), headteachers (35.57 ± 7.39) < school-level leaders and above (41.11 ± 7.15); in the burnout dimension F = 16.387, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that class teachers (24.78 ± 6.52) > middle-level school leaders (22.51 ± 6.02), class teachers (24.78 ± 6.52) > school-level leaders and above (20.54 ± 6.11), headteachers (24.87 ± 6.62) > middle-level school leaders (22.51 ± 6.02), headteachers (24.87 ± 6.62) > school-level leaders and above (20.54 ± 6.11); teachers in different positions did not differ statistically in the secondary trauma dimension (F = 1.355, p = 0.255).

3.2.3. The Influence of Teaching Titles on CS and BO

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences in the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma among teachers with unclassified, primary, middle, and senior titles, showing that in the dimension of compassion satisfaction F = 12.120, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that teachers with the unclassified title (36.65 ± 6.66) > teachers with the primary title (34.45 ± 8.10), teachers with the primary title (34.45 ± 8.10) < teachers with the middle title (36.26 ± 7.68); in the burnout dimension F = 16.387, p < 0.001, post hoc comparisons revealed that teachers with the unclassified title (23.57 ± 6.47) < teachers with the primary title (25.85 ± 6.66), teachers with the primary title (25.85 ± 6.66) > teachers with the middle title (24.37 ± 6.61); teachers with different titles did not differ significantly in the secondary trauma dimension (F = 2.954, p = 0.032).

3.2.4. The Influence of Educational Background on CS and BO

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences in the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma among teachers with a college degree or below, a bachelor’s degree, and a graduate degree or above, showing that in the compassion satisfaction dimension F = 4.741, p = 0.009, a post hoc comparison revealed that teachers with a college degree or below (37.66 ± 7.38) > teachers with a bachelor’s degree (35.95 ± 7.69); in the burnout dimension F = 6.240, p = 0.003, and by post hoc comparison, it was found that teachers with a college degree or below (22.95 ± 6.73) < teachers with a bachelor’s degree (24.59 ± 6.49); there was no significant difference in the secondary trauma dimension among teachers with different degrees (F = 2.184, p = 0.893).

3.2.5. The Difference between CS and BO among Different Types of School

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences in the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma among primary school, secondary school, ordinary high school, and secondary vocational school teachers. The results showed that in the dimension of compassion satisfaction, F = 14.039, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that primary school teachers (37.74 ± 7.32) > secondary school teachers (34.95 ± 7.82), primary school teachers (37.74 ± 7.32) > ordinary high school teachers (35.44 ± 7.92); in the dimension of burnout, F = 15.536, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that primary school teachers (22.99 ± 6.50) < secondary school teachers (25.56 ± 6.67), primary school teachers (22.99 ± 6.50) < secondary vocational school teachers (24.73 ± 5.97); in the dimension of secondary trauma, F = 9.540, p < 0.001, a post hoc comparison revealed that primary school teachers (24.43 ± 6.61) < secondary school teachers (26.25 ± 6.09), primary school teachers (24.43 ± 6.61) < secondary vocational school teachers (26.10 ± 6.04).

3.3. The Effect of Demographic Information on Compassion Fatigue

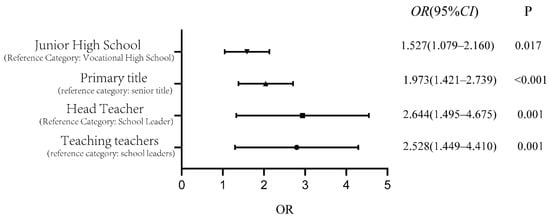

The 1416 primary and secondary school teachers with compassion fatigue were analyzed by using their compassion fatigue degree as the dependent variable and region, gender, teaching experience, teaching subject, position, title, education, location, and school type as explanatory variables in an ordered logistic regression analysis using SPSS25 statistical software. First, all explanatory variables were introduced into a multivariate ordered logistic regression, and the results of the parallelism test were χ2 = 55.885, p = 0.108 > 0.05, indicating that the ordered logistic regression analysis was suitable. Secondly, the insignificant variables in the regression analysis were gradually removed until all the variables entered into the regression analysis were significant. Finally, it was found that teachers’ position, title, and the school type had a significant impact on the explanatory variables, and the other explanatory variables were eliminated.

The parallelism test is the basis for determining whether the multivariate ordered logistic regression model is applicable. At this point, the result of the parallelism test was χ2 = 9.415, p = 0.400 > 0.05, which indicates that the ordered logistic regression analysis was still suitable. According to the model fit information-2 log likelihood values of 463.807 and 368.373, respectively, and the likelihood ratio chi-square value of 95.434, p < 0.001, the model fit for the three explanatory quantities of position, title, and the type of school they teach was better than the model containing only the constant term. The results of further analysis are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The results of the logistic regression of the influencing factors of compassion fatigue among the primary and secondary school teachers. Logistic regression compares each category to one reference category. The odds ratio (OR) represents the odds that an outcome will occur given a particular exposure, compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure. p-value is a statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data. The 95% confidence interval (CI) is a range of values that can be 95% confident contains the true mean of the population.

3.3.1. The Impact of Teachers’ Position on Compassion Fatigue

Taking leaders at school level and above as the control group, the partial regression coefficients of class teachers and headteachers’ job variables were 0.927 and 0.972, respectively, which had a positive impact on the degree of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers at the 1% statistical level, that is, class teachers and head teachers had a greater impact on the severity of compassion fatigue than leaders at the school level and above. When other conditions remained unchanged, the OR value of compassion fatigue severity of class teachers was 2.528 times higher than that of leaders at the school level and above (95% CI: 1.449–4.410), χ2 = 10.659, p = 0.001. The OR value of compassion fatigue severity of head teachers was 2.644 times higher than that of leaders at the school level and above (95% CI: 1.495–4.675), χ2 = 11.180, p = 0.001.

3.3.2. The Impact of Teachers’ Title on Compassion Fatigue

Taking the senior title as the control group, the partial regression coefficients of current primary-title teachers was 0.679, which had a positive impact on the degree of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers at the 1% statistical level, that is, the primary title had a greater impact on the severity of compassion fatigue than the senior title. When other conditions remained unchanged, the OR value of compassion fatigue severity of primary-title teachers was 1.973 times higher than that of senior-title teachers (95% CI: 1.421–2.739), χ2 = 16.449, p < 0.001.

3.3.3. The Impact of School Type of Teachers on Compassion Fatigue

Taking secondary vocational school as the control group, the partial regression coefficient of current secondary school teachers was 0423, which had a positive impact on the degree of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers at the 5% statistical level, that is, secondary school had a greater impact on the severity of compassion fatigue than secondary vocational school. When other conditions remained unchanged, the OR value of compassion fatigue severity of secondary school teachers was 1.527 times higher than that of secondary vocational school teachers (95% CI: 1.079–2.160), χ2 = 5.706, p = 0.017.

4. Discussion

Compassion fatigue is a unique form of teacher burnout, which will affect the physical and mental health of primary and secondary school teachers. When passionate teachers are exhausted due to compassion fatigue, their involvement in education and teaching will be reduced, and they will become indifferent and impatient to students, which will have a bad influence on the school and students, and even lead to moral anomie and resignation of teachers. In this study, 92.73% of primary and secondary school teachers had mild or above compassion fatigue, indicating that the problem of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers should not be ignored.

4.1. Detection Situation of Compassion Fatigue of Primary and Secondary School Teachers

Education can easily lead teachers to burnout as a unique helping profession with high emotional involvement and workload. Many studies also show that teachers are a high incidence group of job burnout [19,20]. Compared with research on teacher burnout, research findings on teacher compassion fatigue—a specific form of teacher burnout—are limited. However, existing studies have also shown that teachers suffer from high levels of compassion fatigue. For example, Borntrager et al. (2012) conducted the first survey of compassion fatigue among teachers in the northwestern United States [21]. They found that approximately 75% of teachers suffered from high levels of compassion fatigue. In June 2020, a survey of 2113 teachers in Alberta, Canada, Kendrick found that 49.6% of teachers had moderate compassion fatigue or above [10]. In this study, 92.73% of primary and secondary school teachers had mild compassion fatigue and above, and more than 44.33% of primary and secondary school teachers had moderate compassion fatigue and above, which is more consistent with the above findings. This may be related to teachers being exposed to pressure sources for a long time in their work practice. They need to deal with various educational and teaching problems and need to establish and maintain a good teacher–student relationship and take the initiative to care for and help students more. Therefore, teachers are prone to compassion fatigue.

4.2. Differences in Dimensions of Compassion Fatigue of Primary and Secondary School Teachers

The statistical analysis found that there are significant differences in compassion satisfaction between teachers in the eastern and mid-western regions, and there are significant differences in secondary trauma. This may be related to the relatively developed economy and extensive investment in education in the eastern region and the relatively high proportion of left-behind children and children with a traumatic experience in the western region. In the dimensions of compassion satisfaction and burnout, there are significant differences among teachers with different teaching experiences, positions, titles, and educational backgrounds, and there are differences among teachers in different school types in the three dimensions of compassion fatigue.

First, from the perspective of teaching experience, teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience had a significantly higher compassion satisfaction than teachers with 0–3, 4–9, and 10–20 years of teaching experience, and teachers in the other three age groups did not have statistically significant differences in their compassion satisfaction from each other. Education is a career with a long return cycle, and primary and secondary school teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience are likely to gain a high sense of personal achievement. On the one hand, with the continuous enrichment of their work experience, they obtain richer educational resources and develop professional skills to a higher level; on the other hand, it is also possible that teachers in this age group are already in a stable stage in various aspects such as family, and can receive more social support and a higher sense of satisfaction. The burnout scores of teachers with more than 20 years of teaching experience are significantly lower than those of the other three teaching experience groups, and teachers with 4–9 years of teaching experience have the highest scores in this dimension. This may be because most of the teachers in this age group have adapted to the teaching work, but they are also getting married and having children. The double pressure of family and career makes them exhausted and burned out.

Secondly, from the perspective of position, class teachers and headteachers had significantly lower compassion satisfaction and significantly higher burnout scores than middle-level school leaders and school levels and above. This may be related to the fact that they spend more time in direct contact with students, need to spend more energy on relationships with students, and are under pressure to improve student performance [22].

Thirdly, from the perspective of title, in the compassion satisfaction dimension, teachers with the primary title scored significantly lower than teachers with unclassified, middle, and senior titles, and teachers with the middle title scored lower than teachers with the senior title; in the burnout dimension, teachers with the primary title scored significantly higher than teachers with unclassified, middle, and senior titles, and teachers with the intermediate title scored higher than teachers with the senior title. In China, title affects teachers’ sense of self-achievement to a certain extent and is related to their career development, remuneration, and professional status. Generally, the higher the title of a teacher, the higher the treatment and the more respect they can receive. The shortage of middle and senior posts is the most apparent contradiction in evaluating and recruiting titles of primary and secondary school teachers. For unclassified teachers, the junior title is a natural promotion process for most teachers, so there is little pressure on promoting the title. However, the middle title is now close to saturation in many schools. For teachers with the primary title, the promotion of the middle title is a necessary part of their career, but due to factors such as uneven distribution of teacher title positions in various schools, many teachers with the primary title have to pay more for the promotion to the middle title. Hence, their compassion satisfaction is lower, and burnout is higher. Teachers with the middle title have the desire to be promoted to the senior title but have certain expectations about the difficulty of evaluation, so the score difference of compassion satisfaction and burnout dimension is not as significant as that of teachers with the primary title.

Fourthly, from the perspective of educational background, the compassion satisfaction of teachers with a college degree and below is significantly higher than that of teachers with a bachelor’s degree and graduate degree and above, and the burnout score is significantly lower than that of teachers with a bachelor’s degree and graduate degree and above. This may be because teachers with a college degree or below are mainly distributed in primary schools, and primary schools have relatively no pressure to enter a higher school. It is relatively simple to deal with the teacher–student relationships with primary school students. It is also more accessible for primary school teachers to feel a positive response to their care for students. This is also consistent with the different situations of compassion fatigue among teachers in different types of schools.

Fifthly, from the perspective of school type, the compassion satisfaction of primary school teachers is significantly higher than that of secondary school and ordinary high school, which may be related to the high status of primary school teachers in the eyes of students. Relatively speaking, primary school students respect their teachers more and can better complete the tasks required by teachers, so primary school teachers can receive a better sense of satisfaction. In the compassion fatigue section, secondary school teachers scored higher than primary school teachers at the 1% significant level, and secondary vocational school teachers scored higher than primary school teachers at the 5% significant level. This may be related to the fact that secondary school teachers should not only establish a good teacher–student relationship with adolescent students but also face the pressure of high school entrance examination; among secondary vocational teachers, the proportion of nonnormal graduates is higher, they lack coping skills in student education and management, and the management of secondary vocational students is relatively complicated, which also quickly leads to their compassion fatigue.

4.3. The Influence of Group Types on Teachers’ Compassion Fatigue Levels

According to the ordered logistic regression analysis of the level of compassion fatigue of primary and secondary school teachers, the position, title, and the type of school they teach have predictive effects on the compassion fatigue degree of teachers. Headteachers and class teachers spend the longest time directly facing and communicating with students, especially when they need to face and care for students with traumatic experiences, which may mean that these teachers are more likely to experience or elevate the degree of compassion fatigue. Compared to teachers with the senior title, teachers with the primary title need to face the pressure of evaluating and hiring the middle title, while teachers with the primary title generally have 3 years of teaching experience; for young people who graduate from colleges and universities to become teachers, this is also a time when they are ready to get married and have children. Therefore, they will face the dual pressure of personal life and career development and will likely develop compassion fatigue. The secondary school teacher community is one group that needs the most attention. They are under pressure to select students for the high school entrance examination, but secondary school students in adolescence are generally more challenging to manage than primary and high school students. The development of compassion fatigue not only affects the physical and psychological conditions of teachers themselves, with teachers as a participant in the teacher–student relationship, students may also be negatively affected when teachers experience burnout and compassion fatigue, especially for secondary school students in the critical period of physical and mental development [23]. Therefore, there is a greater need for secondary schools to take steps to make teachers aware of compassion fatigue and its consequences and carry out prevention and intervention.

4.4. Merits and Limitations in the Current Study

This study examined the current status of Chinese teachers’ compassion fatigue and differences in demographic factors. The current study has some merits and limitations. First, compassion fatigue is a unique mental health issue that can occur after helping people by empathizing, caring, and helping others. In the helping profession, compassion fatigue as a particular kind of burnout is the price of caring. Teachers are exposed to stressors for long periods of time in their work practices, not only to deal with various educational and teaching issues but also to establish and maintain good teacher–student relationships and take the initiative to give more care and help to students, so they are prone to the problem of compassion fatigue, which leads to inappropriate teacher behaviors and affects the professional ethics of teachers. Yet, this issue has not yet attracted attention in China. The current study mainly explored the current situation of Chinese primary and secondary school teachers’ compassion fatigue and the influence of demographic factors on compassion fatigue. Subsequent studies can further explore the factors affecting primary and secondary school teachers’ compassion fatigue, study the influencing factors of teachers’ compassion fatigue in depth, and propose targeted coping strategies to provide data for international research on compassion fatigue.

Second, this study used the Chinese version of the ProQOL-5 scale to conduct the first questionnaire survey on the current situation of compassion fatigue among 1558 primary and secondary school teachers in 28 provincial-level administrative regions in China, which provides a comprehensive understanding of the current situation of compassion fatigue among primary and secondary school teachers in China. The study not only focused on the effects of individual factors and group types on the degree of compassion fatigue among primary and secondary school teachers, but also on the differences in compassion fatigue among teachers in the eastern and western regions of China, trying to understand the differences in the occurrence of compassion fatigue among teachers in regions with different economic levels, educational inputs, and family parenting styles. This is of great importance to enrich the current international research findings on teacher compassion fatigue and to prevent teachers’ professional ethical failures due to compassion fatigue. However, it is worth noting that although the sample size of the current study is widely distributed, there are large differences in the number of investigators. Although the overall sample size in the eastern, central, and western regions is not very different, the sample size in some provinces is still relatively small, and the study could be more optimized if some samples were added in these provinces.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the current status of Chinese teachers’ compassion fatigue and differences in demographic factors through a research study involving 28 provinces, cities, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government in the eastern, central, and western regions of China. The findings revealed that Chinese primary and secondary school teachers had an intermediate quality of professional life and generally experienced more than mild compassion fatigue; individual differences in teachers’ levels of empathy satisfaction and burnout existed. The findings of this study suggest that education authorities or school administrators should pay more attention to teachers’ compassion fatigue while paying attention to primary and secondary school teachers’ burnout, help teachers recognize compassion fatigue and improve controllable adverse environmental factors; and actively carry out prevention and interventions for primary and secondary school teachers’ compassion fatigue. At the same time, teachers need to clarify the boundaries of their professional competence: teachers need to take responsibility for their profession, but not all of it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and X.Y. (Xiajun Yu); methodology, X.Y. (Xiajun Yu); software, M.Z.; validation, X.Y. (Xiajun Yu), F.D. and C.S.; formal analysis, X.Y. (Xuhui Yuan); investigation, X.Y. (Xiajun Yu); resources, B.S.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y. (Xuhui Yuan); writing—review and editing, B.S.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, X.Y. (Xiajun Yu); funding acquisition, X.Y. (Xiajun Yu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number [31871124]. And The APC was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the Zhejiang Normal University (No. ZSRT2022020) on 11 January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thanks the project of Open Research Fund of College of Teacher Education (No. jykf20042) for their support in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Okojie, M.C. The changing roles of teachers in a technology learning setting. Int. J. Instr. Media 2011, 38, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, L.; Buese, D. The changing roles of teachers in an era of high-stakes accountability. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 44, 519–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaafar, S.; Freeman, S.; Spencer, B.; Earl, L. Experiencing secondary school reform: Students, teachers, and administrators. Orbit 2005, 35, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caring. In Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers, and Educators; Stamm, B.H., Ed.; Sidran: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Joinson, C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing 1992, 22, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.R.; Anderson, R.A. Compassion Fatigue: An Application of the Concept to Informal Caregivers of Family Members with Dementia. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 408024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holcombe, T.M.; Strand, E.B.; Nugent, W.R.; Ng, Z.Y. Veterinary social work: Practice within veterinary settings. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2016, 26, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.H. Empathy: Teachers’ professional ability. Jiangsu Educ. 2017, 64, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, S. Compassion Fatigue Is Overwhelming Educators During the Pandemic. Education Week 2021. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-compassion-fatigue-is-overwhelming-educators-during-the-pandemic/2021/06 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Merriman, J. Enhancing counselor supervision through compassion fatigue education. J. Couns. Dev. 2015, 93, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, T.A.; Perozzi, B.; Li, W.J. Issues and challenges in student affairs and services work: A comparison of perspectives from Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. J. Aust. N. Z. Stud. Serv. Assoc. 2015, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. Mindfulness in Context: A Historical Discourse Analysis. Contemp. Buddhism 2014, 15, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, T.Z.; Lu, S.; Jin, Z.F. Primary and Secondary School Teachers’ Title Evaluation Evolution: Key Problems and Policy Suggestions in China. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2017, 12, 66–72 + 78. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, B.H. Comprehensive Bibliography of the Effect of Caring for Those Who Have Experienced Extremely Stressful Events and Suffering. The Concise ProQOL Manual. 2010. Available online: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/dfc1e1a0-a1db-4456-9391-18746725179b/downloads/Effect%20of%20Caring%20Bibliography%2011-2010.pdf?ver=1622779181098 (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- Levine, R.V.; Martinez, T.S.; Brase, G.; Sorenson, K.J. Helping in 36 U.S. cities. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Kirkpatrick, K.L.; Rude, S.S. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.H.; Lou, B.N.; Li, W.J.; Liu, X.W.; Fang, X.H. Attention for the Mental Health among the Helpers: The Connotation, Structure and Mechanism of Compassion Fatigue. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.C.; Qi, Y.J.; Zang, W.W. Overall Features and Influencing Factors of Primary and Secondary School Teachers’ Job Burnout in China. J. South China Norm. Univ. 2019, 1, 37–42+189, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, B. Hudnall. In The ProQOL Manual: The Professional Quality of Life Scale: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout & Compassion Fatigue/Secondary Trauma Scales; Sidran: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager, C.; Caringi, J.C.; van den Pol, R.; Crosby, L.; O’Connell, K.; Trautman, A.; McDonald, M. Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2012, 5, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, B.S.; Cross, L.H. Predictors of Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Stay in Teaching: A Comparison of General and Special Educators. J. Spec. Educ. 1992, 25, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Rodger, S.; Specht, J. Educator burnout and compassion fatigue: A pilot study. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 33, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).