1. Introduction

Bamboo is mainly distributed in tropical and semitropical belts and is a typical resource found in Asia, Central and South America [

1]. The world’s bamboo consists of 1662 species from consisting of 121 genera, which are naturally distributed in 122 countries. As a tropical country of South East Asia, Indonesia has significant potential bamboo resources to be developed. Widjaja [

2] reported that Indonesia has recorded 176 bamboo species, of which 140 are considered native and 105 species known to be endemic, with 20 bamboo species yet to be scientifically described. However, only 108 of these bamboo species have been identified by the community for their usefulness, with 15 species regarded as most useful and, thus, commonly traded commercially. These useful species are harvested both for their poles and for being sources of raw materials, as well as such as shoot, for bamboo products.

In general, bamboo has three groups of main uses: (1) for subsistence purposes, and domestic household use (e.g., house materials, cages, farm tools, as a vegetable trellis, trellis post, shade trellis, etc.); (2) commercial production use in construction, food, and arts (e.g., concrete, reinforcement, fishing rods, furniture, crafts, edible bamboo shoots, musical instruments, engineered bamboo products, etc.); and (3) ornamental, landscape, and conservation use (e.g., riparian buffers, plant specimens, screens, hedges) [

3].

In Indonesia, bamboo has been an important part of history, socio-cultural tradition and activities, and community livelihood pursuits [

4,

5,

6]. The bamboo plant is mainly found in the mixed garden where it grows with other flora such as trees, shrubs, palms, and understory vegetation [

7,

8,

9,

10]. The community utilizes it for daily needs, for crafts and weaving, and as traditional building material [

11,

12]. However, bamboo-related earnings and business types that were undertaken have failed to significantly increase the income of the people because the commodity’s added value remain low and because bamboo processing continues to be regarded as a side job [

13,

14]. Rabik and Ekawati [

15] write that community-based bamboo development could be the force for advancing the high-value-added bamboo industry through integrated cross-sectoral support in Indonesia. Using community bamboo as the supply of materials for the industry with appropriate processing and machinery for more value-added products can provide additional household income in rural areas [

15].

Modern utilization on a community industrial-scale should create more opportunities for adding value to bamboo in order to increase the community’s income. This has been proven in China as seen in the report of Flynn A et al. [

15], and Ruiz-Perez M et al. [

16] regarding how bamboo development increased farmers’ income by 28.4% and played an important role in the industrial development of rural areas in Anji County, Zhejiang Province. In the same situation in Linan County located in the southern part of Anji, bamboo sector reform and other initiatives significantly increased the role of the bamboo sector in the local economy. Income derived from bamboo also plays an essential role in moving many households from the poor to the wealthier classes [

17]. However, there has been no research on the utilization of community bamboo resources as a supply of industrial raw materials in Indonesia because not many industries process bamboo into modern products on a large scale [

18].

The bamboo development program in Ngada Regency was initially carried out through the planting of a million bamboo under a collaboration program between the Environmental Bamboo Foundation (EBF) and the local government of Ngada Regency in 1995, which also corresponded as a recovery program of the 1992 Maumere earthquake. Subsequently, from 2006 to 2008, the central and local government carried out a bamboo nursery and planting program targeting 500 ha of land area [

19]. In 2007, the local government, in collaboration with the Gadjah Mada University, undertook a feasibility study for the bamboo business development in various levels based on its utilization [

20]. The feasibility study [

20] revealed that Ngada has the potential of abundant bamboo product supply based on the existing raw bamboo resources in the area. Thus, the study in effect pointed to how bamboo utilization has not been optimized. Worth noting is how the study provided recommendations for modern bamboo having added value, such as laminated bamboo products, on medium and large industrial scales. In 2012, a bamboo processing factory was thereafter established, producing preserved bamboo strips and sticks as half-finished materials for engineered bamboo products. This factory processes community bamboo by applying selected harvesting because the raw material requirement for their bamboo product is limited to four-year-old bamboo poles.

From those baseline programs, Ngada has become a pilot model of community-based integrated bamboo development from upstream to downstream through the involvement of various stakeholders. The model refers to the utilization of bamboo and the direct interaction of the community on bamboo management. Later, in 2016, an initiative was conducted by the EBF, in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and Forestry through a movement called Thousand Bamboo Villages, as a platform for integrated community-based bamboo industry development in Indonesia. Following the initiative, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the Ministry of Industry, and the local government launched the center for community-based bamboo industry development as a running model of implementation in the country [

18].

As a model of the community-based bamboo development center, Ngada has fulfilled the requirement of the upstream sector with its great potential of existing community bamboo resources, and the established preserved bamboo strip processing industry as existed in the area to support the downstream sector. However, the driving and the barriers factors in the implementation of the community-based bamboo supply for industrial purposes are yet to be identified. However, from the time the bamboo development center began operations in 2012 until today, many challenges still confront the development of processing preserved bamboo strips. In the same situation with the community, bamboo owners as bamboo suppliers should fulfill the requirements for bamboo age and sustainable management. Therefore, this study aims to provide strategic recommendations by determining and assessing drivers and barriers for the success of community-based bamboo supply for industrial-scale utilization in Ngada Regency in Indonesia.

3. Results

3.1. The Bamboo Resources

In general, Ngada Regency’s climate condition and topography are suitable for bamboo’s optimal natural growth and its cultivation. However, the existing bamboo resources consist mainly of traditional species, and bamboo has not been cultivated like other superior commodities produced from this area, such as coffee, candlenut, and cashew nuts. Nonetheless, bamboo grows well in Ngada Regency, and there are currently 15 bamboo species have been recorded, as shown in

Table 1. There are three important bamboo species that are commonly found and widely used by communities in their daily life:

Dendrocalamus asper (

betung/bheto),

Gigantochloa atter (atter/peri), and

Bambusa vulgaris (

aur/guru) [

19]. A study by Sada and Jumari [

23] reported that Ngadha ethnic, the most enormous ethic in Ngada Regency, has a long history dating back to their ancestral heritage relating to the use of plants as part of their traditional ceremonies. In addition to paddy

padi or

pare (

Oryza sativa L.) and corn

jagung or

sae (

Zea mays L.), bamboo is regarded as a crucial plant. Several bamboo species are used in daily life in the form of various products and also as artifact for ceremonial activities are

aur/guru bamboo (

Bambusa vulgaris),

peri bamboo (

Gigantochloa atter),

betung bamboo (

Dendrocalamus asper), and

wuluh bamboo (

Schizostachyum latifolium).

The Ngada Regency of Statistic Bureau [

24] reported an estimated 90,000 bamboo clumps owned by the Ngada Regency community in 2017 and 2018 (

Table 2). Bajawa, Golewa Barat, and the Golewa sub-districts, which together contribute 38% of the regency’s population, are the largest bamboo ownership contributors, accounting for 80% of the total. The use of bamboo resources in these areas is more intensive than in the rest of Ngada Regency. This is also supported by good accessibility between the three neighboring sub-districts. Moreover, because Bajawa is the capital of Ngada Regency, the cluster is inclined to become the center of economic activities.

Community-owned bamboo can be likened to traditional villages in Ngada. The current condition of bamboo resources can be seen based on satellite imagery/aerial photo showing the land, with doughnut-like pattern, covered with what has been validated as bamboo covers. The village, known as

kampung adat is clearly surrounded by bamboos (

Figure 2). This area is captured in Ratogesa village, Golewa sub-district, which explains that bamboo become an integrated part of community life. Interestingly, there exists a customary law (

waja or

ri’i), which is a part of local wisdom in Ngada, obligating the community to recover bamboo resources whenever the land undergoes any damage due to over-harvesting. This rule that is very strict, even accompanied by sanctions, ensures the recovery of bamboo in several years (about 5–10 years) with no harvesting.

3.2. Bamboo Management

Section 3.2. Bamboo Management and

Section 3.3. Community’s Perception of Bamboo was presented from the result of 119 bamboo owners and farmer questionnaires. The community-owned bamboo resources in Ngada Regency were divided into two types: (1) owned by individuals (67%), and (2) owned by communal (33%), as seen in

Figure 3. The communal bamboo resources are usually managed collectively in the community’s tribe or sub-tribe groups. The management and utilization of the communal bamboo resources must be carried out based on the approval and agreement of the sub-tribe groups, which is facilitated by the group’s leader. On the other hand, individual bamboo owners have more freedom to use and sell their bamboo at any time.

The use of bamboo in the community continues to increase, particularly those relating to economic activities. Many bamboo resources have encouraged variations in utilization to provide the added economic value, orienting to be a bamboo industry. In 2015, a bamboo management system called sustainable bamboo forestry (SBF), in collaboration activities with the EBF and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), was introduced to ensure sustainability in the use of community bamboos [

18]. This bamboo management system was applied as a requirement for the supply of raw materials to the industry. The Golewa sub-district became the first area to implement the SBF system on community-owned bamboo for the supply of the existing bamboo factory.

Regarding bamboo management, six of twelve sub-districts (Bajawa, Golewa, Golewa Barat, Golewa Selatan, Jarebuu, and Soa) have been socialized and introduced to the SBF system. However, currently, only three sub-districts (Bajawa, Golewa, and Golewa Barat) are actively implementing the system to fulfill the supply of bamboo raw materials to a local factory manufacturing preserved strips products [

24]. However, this bamboo management system is only carried out for the industrial supply of preserved bamboo strips as the utilization of other bamboo products does not implement a bamboo clump maintenance system.

Results of questionnaires from the first group of respondents (bamboo owners or bamboo farmers) as representative of upstream sectors were collected from the targeted five sub-districts having a high potency of bamboo resources (

Table 2), namely sub-districts; Bajawa, Golewa, Golewa Barat, Riung Barat, and Wolomeze. The respondents mostly come from the Riung Barat sub-district (27.73%), followed by the Bajawa sub-district (24.37%), and the Golewa sub-district (21.85%). The result showed that 78% of respondents leave their bamboo resources unmanaged and only 22% of respondents managed their bamboo using the SBF system, as shown in

Figure 3. The respondents who applied the SBF system were found to come from the Bajawa, Golewa, and Golewa Barat sub-districts. These three areas are known suppliers for the preserved bamboo strips or sticks industry.

Since bamboo can be grown with other types of plants, the questionnaire also collected data on bamboo planting patterns owned by the community. The bamboo resources in the agroforestry system have become an important element of the community livelihoods [

25,

26,

27], especially in traditional villages and rural area in Indonesia [

6,

8,

9], and in other countries such as in a number of African countries [

27,

28,

29], in India [

30,

31,

32], in China [

33,

34]. In Ngada, there are two types of community bamboo resource utilization, namely monoculture and mixed or agroforestry bamboo. The monoculture system is used by 56% of the respondents (67 bamboo owners), while the mixed or agroforestry plantation management is used by 44% of the respondents (52 bamboo owners), as shown in

Figure 3. The monoculture bamboo resource management is commonly practiced in Bajawa, Golewa, and Golewa Barat sub-districts, while the agroforestry system management is mainly found in the Riung Barat and Wolomeze sub-districts. The agroforestry system includes a multi-strata canopy, combining bamboo with different heights of plants such as trees and understory plants. In general, this plantation system is practical for people’s daily needs because it combines seasonal and yearly crops. In addition, as an agroforestry system management, community bamboos are usually combined with understory plants, such as

Zingeberaceae spp. and cassava, and also with other seasonal crops for daily use.

3.3. Community’s Perception on Bamboo

The results of this study were gathered from 119 questionnaires collected from respondent bamboo owners and bamboo farmers group. Twenty (20) of the questions in the questionnaires asked bamboo owners and farmers about their perception and opinion on statements concerning the role, resources, and utilization of bamboo. The collected data were analyzed using the SPSS Statistics 25 software to test for validity and reliability. Seventeen (17) out of 20 questions were valid and reliable, as presented in

Figure 4. The results of public opinions and perceptions show that more than 90% of respondents agree that bamboo plays an important role in socio-cultural life and serves the function of maintaining water sources and improving environmental quality, such as fresh air. More than 90% of the respondents support bamboo as a potential local commodity and agree that bamboo should be developed with more added value. The majority of respondents are in favor of the existence of a bamboo processing industry in Ngada. The community perception on the economic benefits of bamboo was diverse: 37.82% agree that bamboo provides economic benefits, 28.57% are neutral or do not know, and 33% of respondents disagree that bamboo is beneficial economically. These results suggest that 33% of respondents have not received direct economic benefits from bamboo; in other words, existing bamboo resources have not been utilized as household income. Another interesting finding is that people nowadays prefer to instead use bricks and cement to build their homes, especially in city areas. This is causing the current need for bamboo for general housing to decrease. While the bamboo houses still exist but it is only in traditional villages that they are properly maintained like the original houses.

In general, the condition of upstream sector as gathered from the results of the survey reveal the following: (1) from the ecological aspect and environmental benefit, Ngada community has the perception that bamboo plays an important role in maintaining environmental quality and water resources; (2) from the socio-cultural aspect, bamboo had become part of culture and tradition, also found in the local wisdom on bamboo preservation; (3) however, from the economic side, the benefits of bamboo have not significantly impacted on the community. For the above reasons, members of the upstream sector support the processing of bamboo with added value into modern products at industrial-scale for optimal utilization of the existing bamboo resources. Furthermore, the community is in agreement as to the need to maintain their bamboo clumps under conditions of good market and bamboo being able to augment household income. They are willing to plant bamboo whenever more of this plant resources needed. The community believes that if the use of bamboo can provide high economic benefits, bamboo can compete with other commodities in Ngada.

3.4. Bamboo Utilization

This section presented the results from the questionnaires responded to by 121 participants of the second group, consisting of bamboo crafters, artisans, and entrepreneurs. The data collection was aimed at identifying existing conditions of the downstream sector related to bamboo utilization and products, including the distribution of crafters, entrepreneurs, and industry. The use of bamboo in Ngada had been mainly for subsistence and daily life purposes and bamboo processing chiefly for woven and handicrafts products at micro and small enterprises level. Clearly, bamboo had not been a commodity for business or industrial-scale purposes.

The feasibility study of potential bamboo business in Ngada Regency provided recommendations showing that available bamboo has an excellent opportunity to be utilized in modern products such as the laminated and construction bamboo industry [

19]. In line with said recommendation, the development of bamboo industry in Ngada began in 2012. The bamboo processing factory that was subsequently built processes community bamboo into preserved bamboo strips and sticks products, as half-finished materials for laminated bamboo as end products. The existence of this factory has increased the use of community bamboo and introduced modern bamboo processing to the community. In addition, the development also introduced the community to the sustainable bamboo clump management system and the selected harvesting system of 4-year-old bamboo poles as required by the industry.

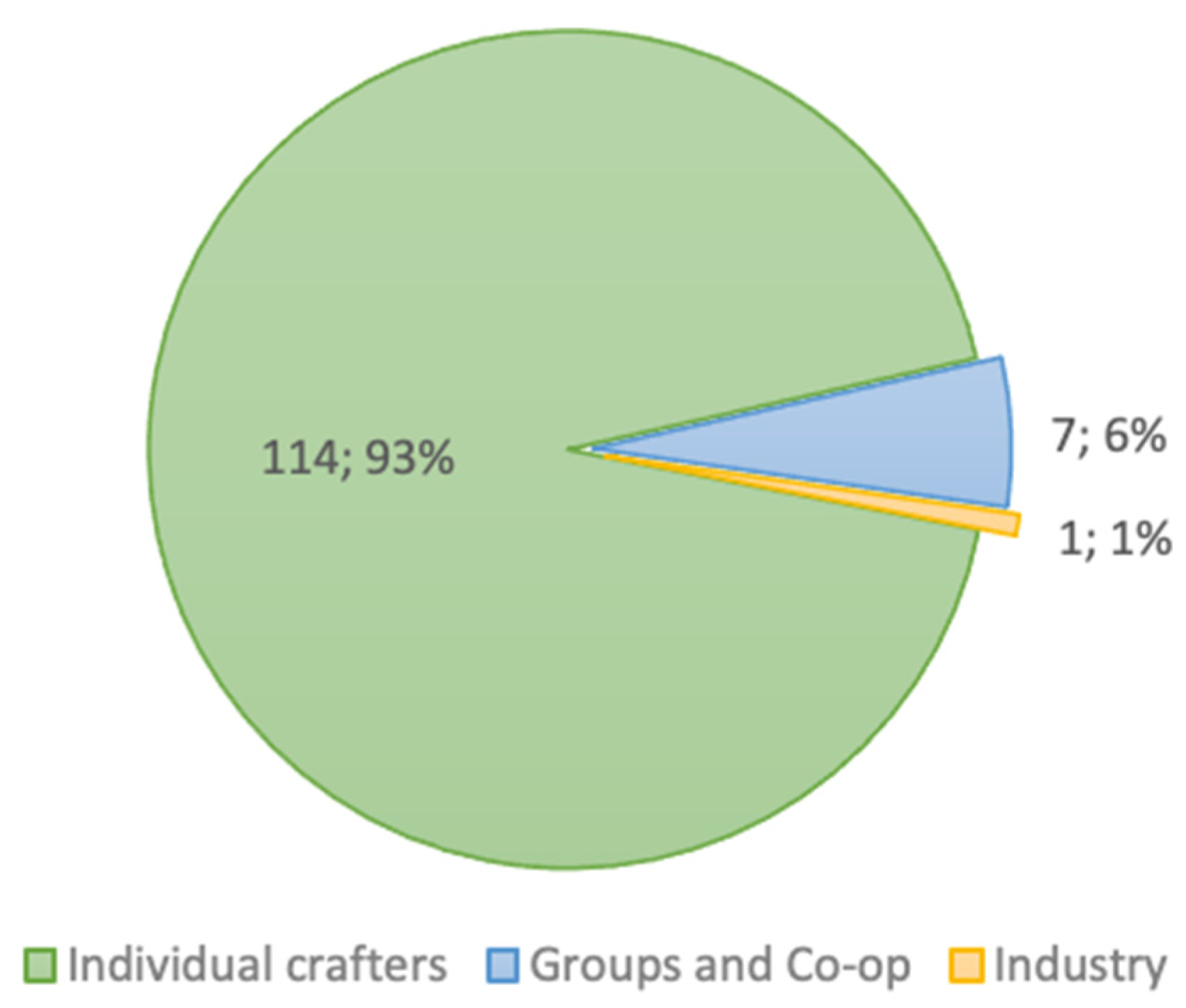

The bamboo utilization data were collected from 121 respondents of the following nine sub-districts: Bajawa, Bajawa Utara, Golewa, Golewa Barat, Golewa Selatan, Inerie, Jerebuu, Riung Barat, and Wolomeze. The study discovered that the actors who process bamboo products are dominated by individual crafters, mainly women on a household scale (114 respondents, or 93% of total), followed by groups or small and medium enterprises and cooperatives (7 respondents or 6%), and only one bamboo processing factory (1%) (

Figure 5).

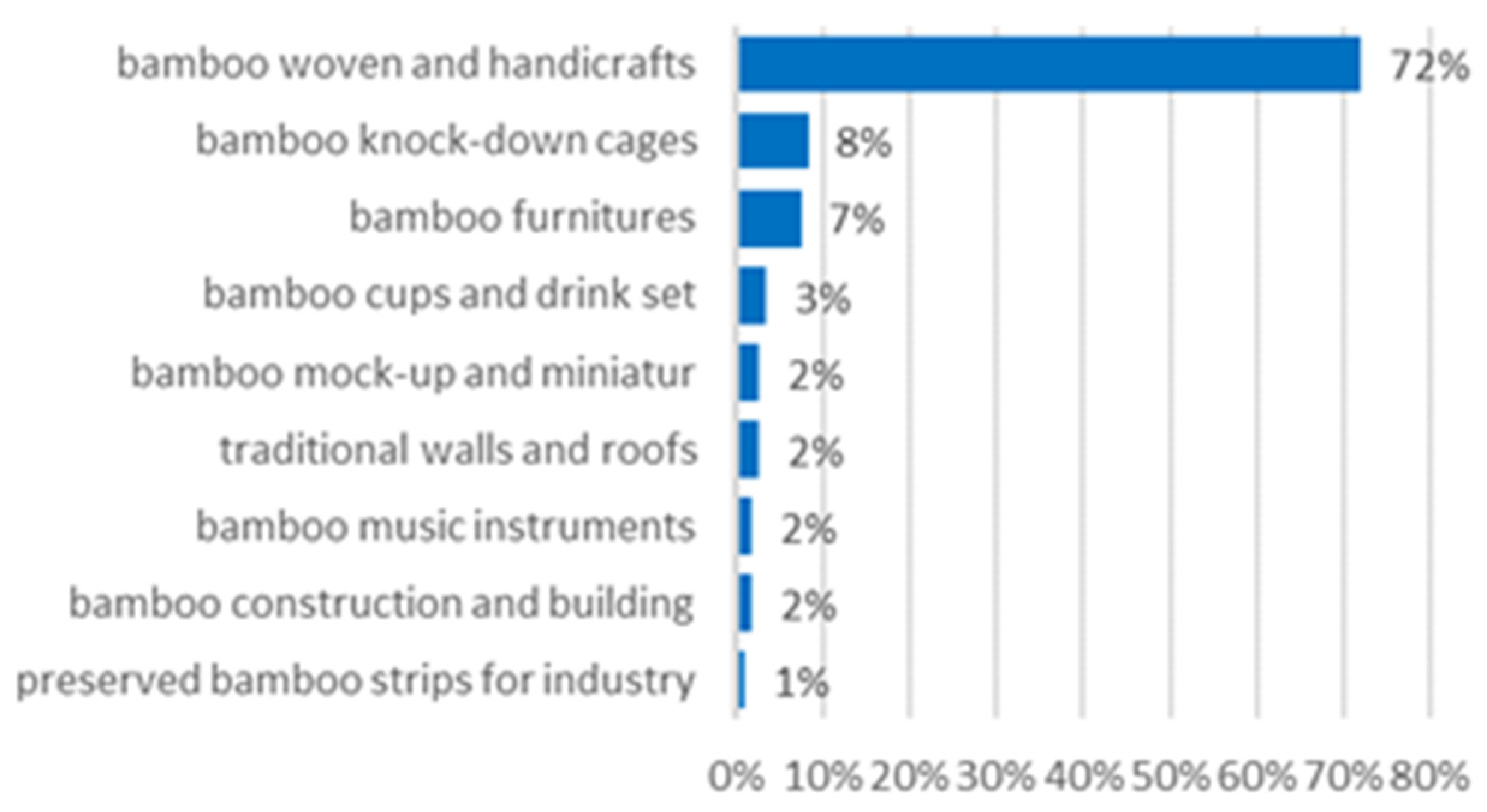

The study showed that in the downstream sectors, bamboo has been utilized in commercial products but mainly only for local and still limited markets. The main bamboo products in Ngada Regency are bamboo woven (72%), which includes handicrafts, baskets, kitchen utensils, and bamboo souvenirs. These are bamboo woven products produced by individual bamboo crafters, who are mostly women. The other products include bamboo cages (8%), bamboo furniture (7%), and bamboo component for structural purposes (3%), as shown in

Figure 6. The majority of the survey respondents said that one of the challenges in the use of bamboo is lack of skills in product development and innovation. Therefore, training and capacity building in the processing and development of bamboo products are crucial. Another challenge is the uncertain market demand for bamboo products. Presently, production is dictated by the quantity of demand from consumers. Although there are already various kinds of bamboo utilization, this study focuses on the use of community-owned bamboo as a raw material for the existing modern bamboo industry in Ngada.

In Ngada, the preserved bamboo strip and stick factory has existed since 2012 and have experienced many ups and downs in their bamboo processing. The problems faced include ensuring the supply of required raw materials from community-owned bamboo resources, specifically 4-year-old bamboo poles [

35]. Therefore, the system of sustainable bamboo management was introduced to the community to fulfill this industry requirement. At the beginning of its operation, the factory received raw materials from Golewa sub-district, which was the first introduced to the SBF system. Currently, the supply has expanded to other sub-districts, such as West Golewa and Bajawa. The factory process bamboo culms into preserved bamboo sticks and strips as half-finished products. The products are then sent to another factory equipped with more advanced technology and machinery in a different area to be processed into engineered bamboo products (i.e., strand-woven bamboo and laminated bamboo).

3.5. Identified Drivers and Barriers

Drivers and barriers in developing community-based bamboo as an industrial-scale raw material supplier were identified from the questionnaires for the bamboo owner group and the artisan-entrepreneur group at the community level, in addition to the semi-structured interviews with expert groups. To obtain the identified driving and inhibiting factors from upstream and downstream sectors and the stakeholders involved, the determination of drivers and barriers factors was conducted by modifying the SWOT approach. The terms strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats are more commonly used and are actually easier for respondents to understand.

The identified factors were classified into the internal drivers (strength), the external drivers (opportunity), the internal barriers (weakness) and the external barriers (threats), as shown in

Table 3.

The results identified that several drivers, both internal and external, have been existing for the development of community-based bamboo resources reserved the following: for industrial purposes in Ngada Regency. These drivers are the following: strong bamboo culture, social capital, local government’s program support, market-driven, transparent system and mechanism on bamboo utilization, and stakeholders’ support. On the other hand, the identified constraints serving as barriers to be overcome include the following: lack of capacity building on modern utilization of bamboo with value-added, shifting from traditional to industrial culture, and some un-support regulation. The identified drivers and barriers on bamboo development were assessed and evaluated by driver and barrier analysis using modified IFE and EFE of SWOT analysis.

3.6. Driver and Barriers Analysis

The drivers and barriers analysis was developed to formulate the strategic recommendation in terms of community-based bamboo resources for industrial-scale supply in Ngada Regency. Several internal–external drivers and barriers factors were recorded based on the results from questionnaires and interviews with expert groups. The internal and external factors as well as the key factors that refer to performance and priority index were identified and classified from FGDs. Based on the results, 18 internal factors are listed, consisting of 9 factors as internal drivers and 9 factors as internal barriers for IFE.

The three highest scores in the internal driver’s factors are: potential bamboo resources, suitable biophysics conditions for growing bamboo, and the existence of a local NGO that facilitates bamboo development. Meanwhile, factors determining the bamboo products value chain have not yet been established. The lack of stakeholders’ capacity in bamboo management and the lack of integrated regulation support on bamboo are found to be equally important internal barriers factors based on the evaluation of total values. The total score of internal driver factors is 1.814, which is lower than the total score of internal barriers, 2.041, suggesting that the weakness factors could be minimized by the internal drivers factors as shown in

Table 4.

We identify seven external drivers and four external barriers (

Table 5) as the external factors. The three highest scores of the external drivers are as follows: central and provincial government support, the existing bamboo strips industry, and market opportunities for laminated bamboo products. While the two highest external barrier factors are changes in land use of bamboo plants for other uses, also the utilization of bamboo without regard to sustainability aspects. The scores of external drivers factors total 2.602, whereas the total scores of external barrier is 1.023, indicating that the drivers are more important than the barriers.

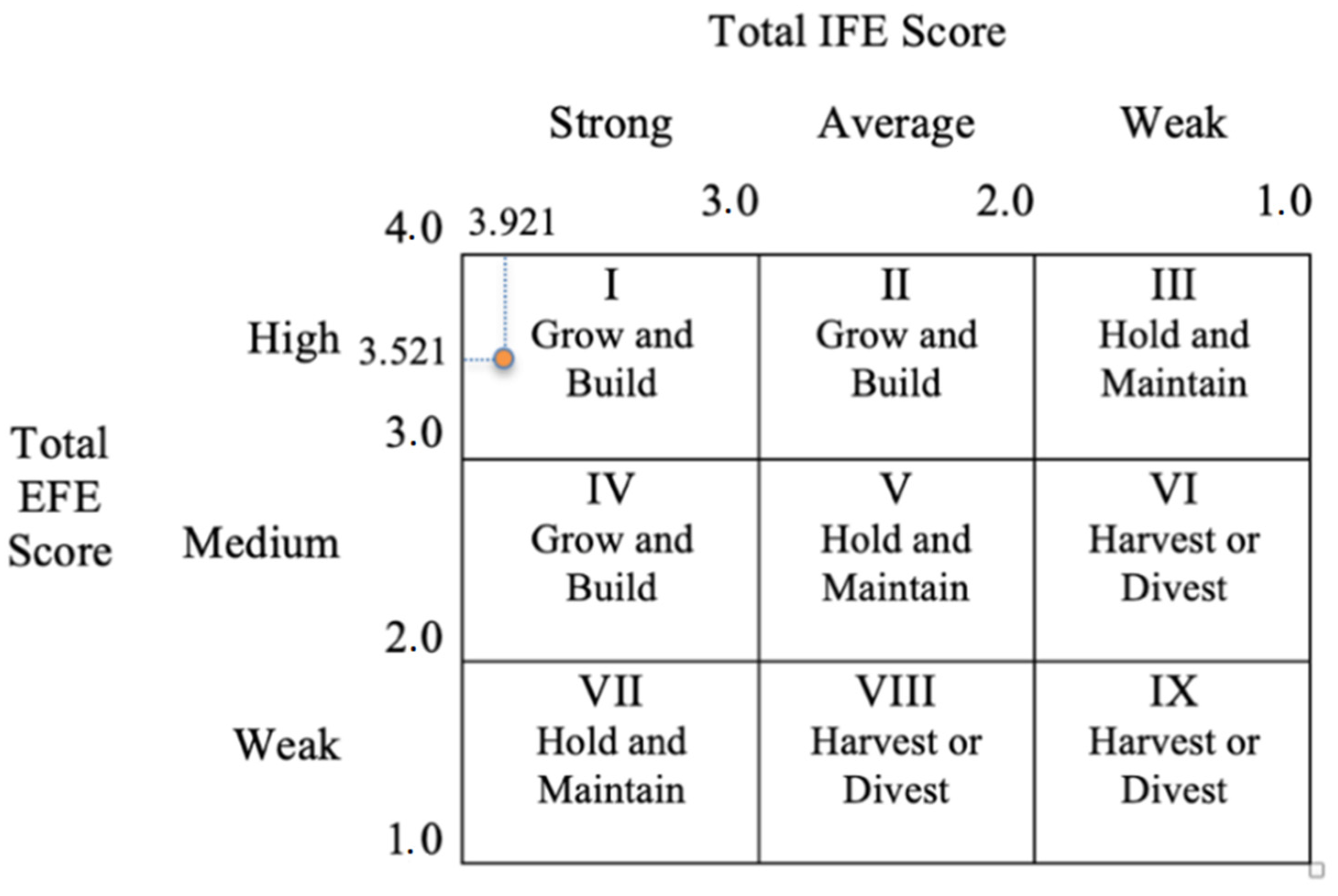

The next step of the analysis involves constructing a matching stage by evaluating and scoring the total of both IFE and EFE to determine the current position and situation (

Figure 7). The scores indicate that the community bamboo resources management in Ngada Regency is growing and improving. This means that the community-based bamboo activities can be geared toward sustainability management, through support from stakeholders involved. Therefore, recommendations on strategies are required for further development.

The final stage of driver barriers analysis found the need to develop strategies in terms of evaluating the drivers and barriers of community-based bamboo resources for industrial-scale’s supply in Ngada Regency. Based on the four sets of alternative strategies, derived from the combination of internal and external factors, ten developing recommendation strategies for the effective implementation of strategies can be formulated, as listed in

Table 6.

The drivers and barriers matrix of

Table 6 above can be summarized as follows: ID–ED strategies, namely, taking maximum advantage from internal and external driver; ID–EB strategies, which is essentially avoiding threats by internal drivers; IB–ED strategies, which are geared toward introducing new opportunities by reduction in internal barriers; and IB-EB strategies which essentially involves avoiding external barriers by minimizing internal barriers. The analysis adopted from the SWOT matrix provided a realistic interpretation of the drivers and barriers of a business and helped in providing an overview of the differences between actual and future plans, as well as in analyzing the current situation [

36].

The community-based bamboo resources to support bamboo development in Ngada Regency are integrated between upstream, middle stream, and downstream sectors, with each sector involving different stakeholders. The formulated ten strategies are thus grouped into different aspects related to (1) resources, (2) people, (3) markets, and (4) policies, which are all connected and mutually supportive.

The resource aspects (upstream) consist of three strategies, namely, (i) planting bamboo through rehabilitation program supported by government, (ii) increasing the sustainable utilization of bamboo resources for wood substitute, bamboo products, and (iii) ensuring the implementation of sustainable bamboo harvesting system, through the SBF system.

The people aspects (middle stream) also relate to three strategies, which are: (i) increasing the capacity building of community and involved stakeholders, (ii) strengthening social capital to support community bamboo industry, and (iii) strengthening the stakeholder’s supports.

The market aspects (downstream) relate to the following: (i) increasing the bamboo value-added to meet the market, (ii) strengthening the value chain of community bamboo industry products, and (iii) increasing bamboo values to compete with other commodity plants. In order to achieve appropriate and synergized implementation of these three aspects, it is beneficial to focus on the policy and regulation on integrated community bamboo industry, as the most important supporting aspect of policy.

In the community-based bamboo resources development, more attention is needed in strengthening the upstream sector (resources) and how it is connected to the downstream sector (markets). Nevertheless, other aspects such as human resources (people) and regulatory support (policy) are also important.

Therefore, it can be seen from the ten formulated strategies in community-based bamboo resources for restoring ecosystems, that there are three priority strategies to support the community-based bamboo resources for industrial-scale supply in Ngada Regency: (1) increasing the capacity building of stakeholders involved in sustainable bamboo management, (2) planting bamboo through a rehabilitation program supported by government, and (3) developing regulation and policy on integrated community bamboo industry. Furthermore, this study provides recommendations for policymakers to develop programs and regulations supporting the community-based bamboo resources to restore the ecosystem, improve livelihood, and contribute to the village’s inclusive economic growth.

4. Discussion

The results of the study reveal that local communities in Ngada Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province, perceive bamboo as part of their daily lives and livelihoods. The strong bamboo culture in the Ngada community has encouraged the people to value the existence of bamboo in their area. The community believes that bamboo has environmental roles and functions such as serving as a water catchment area, providing fresh air, and balancing microclimate. Several studies have shown that bamboo has significant ecological functions, such as the following: protecting the areas of watersheds and water catchment; maintaining the hydrological systems, springs, microclimate, and fresh air; preventing soil erosion; sequestering carbon; providing many other ecosystem benefits [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Bamboo has attracted new opportunities as a source of cultural, aesthetic, and recreational activities as well as several potential climate, watershed, and biodiversity functions [

38]. Based on its ecological function, bamboo is ideal for restoring critical land, especially on necessary land where many plants cannot grow, while planting bamboo can provide economic value benefits for the community [

41,

42,

43]. Many studies have documented that bamboo can make an essential contribution to household income and rural development. China is frequently considered a model or reference due to its long history of community-based bamboo management. It has played an important role in rural development, and its steady expansion proves that bamboo will continue to thrive for a long time [

14,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. They continue to serve as a model for other regions of the world facing rural poverty by developing their bamboo sector, what with the impact of its fast-developing bamboo industry on rural livelihoods.

Several studies reported that bamboo provides economic benefits and generates family income, which significantly impact on rural developments. In the northern part of China, the cultivation of dried bamboo shoots at the small-scale household level has crucially impacted on household income and livelihood. The high-income households have their highest total bamboo income from bamboo shoots, but low-income families depend on bamboo income [

43]. In India’s South Meghalaya area, bamboo mat making also contributes to community livelihoods, especially to women. Making bamboo mats is considered one of the most important jobs and adds to people’s income, especially during the period of the year when jobs are scarce [

49]. Dwivedi et al. [

50] reported that farmers can earn up to USD 800 per hectare annually by selling raw bamboo from their degraded land. Bamboo cultivation can generate around 10 CERs (certified emission reductions) per hectare annually, which can be traded as carbon credits. Additionally, under-employed farmers can work as skilled workers in the bamboo handicraft industry and can earn up to USD 2700 annually (at current exchange rates), which is significantly higher than the present average income (1750 USD/annum) of farmers. In Ethiopia, bamboo has great benefits for income diversification and other socio-economic values related to cultural and medicinal uses for the local community [

51]. In Indonesia, there were several studies regarding bamboo and rural area development. Until now there has been no research that conducts the development of community’s bamboo that purposes as an industrial supply. The use of bamboo that generally exists is mainly for handicrafts, woven bamboo, and other traditional bamboo products in micro and small businesses [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, the potential of community bamboo development as a supply of bamboo utilization on an industrial-scale in Indonesia has not yet been explored.

The success of developing bamboo to improve the rural economy cannot be separated from the social capital owned by the community. The existence of social capital owned can be a strength to further sustainable bamboo development in the community [

58]. Prasetyo [

58] reported that in Ngada Regency, the current existence of bamboo resources is a legacy from their predecessors and parents. This is true not only in Ngada but also in some other areas in Indonesia that have a strong bamboo culture, given that bamboo has existed since time immemorial and is passed down from generation to generation, such as in West Java and Bali [

42,

43,

44]. Because the existing bamboo is a heritage, the community has almost no experience in bamboo cultivation because people simply harvest bamboo that has been growing since they were born. Nowadays, the government put bamboo in the species lists used for rehabilitation and restoration of degraded lands, which basically means they will be planted in activities involving the community. The people who have experience in planting bamboo are those often who are involved in the rehabilitation program carried out by the government. The current existence of ample bamboo in Ngada is in part also partly from the result of the planting program carried out by the local government, civil society, and community after the Maumere earthquake, in 1992 [

59]. A study conducted by Noywuli et al. [

60] gave a recommendation for planting bamboo at the Aesesa Flores watershed, Ngada for the purposes of sustainable watershed management. Moreover, bamboo is a prospective commodity for the community culture, climate, land availability, and markets for industrial supply material. The development of bamboo as an industrial raw material must be supported by the adequacy and availability of sustainable raw materials; therefore, it is necessary to consider increasing the stock of bamboo raw materials for the industry by widespread bamboo planting.

In recent years, the development of technology and innovation has changed the use and utilization of bamboo. Bamboo has become a noble material that can be processed into multiple products with various use. The utilization of advanced technology in construction will contribute to the development and expansion of bamboo applications (buildings, structures, bridges, etc.) [

61]. Endalamaw [

62] reveals that in Ethiopia, the proportion of commercial use of bamboo is roughly a third of total consumption. Understanding local differences in small-scale bamboo commercialization and the factors contributing to it can be used as a basis for further investigation of the pathways for the broader development of the bamboo value chain. Furthermore, the study showed that industry and companies applying knowledge and technology play an essential role in bamboo innovation. The local company assisted by China companies through native sources interactive learning in inter- and intra-company networks. By applying such knowledge, bamboo farmers and companies are able to produce new products and new ways of using bamboo, substantially increasing its durability, quality, and competitiveness [

62].

The existing preserved bamboo strip processing industry in Ngada can be an opportunity for enhancing the community’s bamboo market. Currently, the use of bamboo by the community is still not optimal and is still on a micro-industrial or household scale. Thus, the existence of industrial-scale can absorb the community’s bamboo as raw material. Other important approaches needed for the commercialization process of community-based bamboo development are management intensification of bamboo resources, sustainable rural livelihood, and a strong and robust value chain [

63]. Partiwi et al. [

64] discovered that appropriate strategies to develop bamboo business in the district or regency level involve cluster approach supported by the government.

Policy support in the development of bamboo and its processing industry requires integrated regulation between the upstream sector, the middle sector and the downstream sector. The support from a successful national policy and political framework just as China has done in developing bamboo as a non-timber forest product [

65] commodity is needed. For four decades now, China has been reforming its policies in support of the community economy, especially in rural areas, by building village industries that drive the people’s economy [

66,

67]. Policy support at the regional level also plays an important role. Anji County and Linan County, in Western China, are two areas that are famous as centers of various bamboo products [

15,

16]. These two regions reformed the bamboo sector and made policy changes to support the community-based bamboo development, bamboo industries development, and rural social economy.

Therefore, in this study, the identified factors of drivers and barriers were assessed and analyzed to find out the real situations and conditions for the development of community bamboo as industrial-scale supply. The identified drivers and barriers are used as the basis for the formulation of strategic steps to solve problems; these steps can provide policymakers, decision makers, and related stakeholders with strategies and recommendations to support other policymakers. The regulations and programs that are prepared can answer the needs and problems faced.

5. Conclusions

Bamboo is part of Ngada community in their culture, daily life, and livelihood. The community still shares a traditional paradigm and mindset on bamboo resources and its utilization. The huge potential of bamboo has not been utilized optimally, while the need for local use is decreasing and people have not received significant economic benefits from their bamboo resources. The driving factors for the use of modern bamboo on an industrial scale have been identified. The three highest points of the internal drivers factors are as follows: the potential bamboo resources, suitable biophysics conditions for growing bamboo, and the existence of a local NGO that facilitates bamboo development and sustainable management. The three highest points of the external drivers factors are central and provincial government support, the existing bamboo strips industry, and market opportunities for laminated bamboo products.

However, there are barriers factors that must be overcome to enable the smooth development of modern bamboo utilization with the support of related stakeholders. The three strongest internal barriers are as follows: the yet-to-be-established bamboo products value chain; the lack of stakeholders’ capacity in bamboo management; the lack of integrated regulation support on bamboo. The strongest external barrier factors are the changes in land use and bamboo plants for other uses and also the utilization of bamboo without regard to the sustainability aspects.

Based on the evaluation and assessment carried out by analyzing the situation and development conditions, it was found that the use of modern bamboo on an industrial-scale is growing and improving. Based on the existing drivers and barriers, it is necessary to formulate strategic steps to encourage the current growth and generate favorable conditions. The strategic steps made must be integrated across sectors, upstream, middle and downstream, and involve the role of the various parties. There are ten strategic steps for success that have been formulated based on the identified drivers and barriers, of which three have become priorities, namely, (1) increasing the capacity building of stakeholders involved in sustainable bamboo management, (2) planting bamboo through rehabilitation program supported by government, and (3) developing regulation and policy on integrated community bamboo industry. Therefore, investing in targeted community capacity building enhancements with the application of effective training and transfer knowledge, sustainable bamboo management, and processing skills of industrial culture are needed, as well as appropriate recommendations for policymakers to develop programs and regulations supporting community-based bamboo resources to restore the ecosystem, improve livelihood, and contribute to the inclusive economic growth of the village.