Abstract

Although school education, including the subject of physical education (PE), has the potential to contribute to the visions set out by the 2030 Agenda and its sustainable development goals (SDGs), little attention has been directed towards sustainable development perspectives in PE teacher education (PETE). In this explorative paper, we aimed to investigate how sustainable development perspectives are reflected in Swedish PETE course syllabi, focusing on learning outcomes. The source of data was 496 learning outcomes retrieved from PETE course syllabi at the eight Swedish PETE institutions that examine PE teachers for compulsory school grades 7−9 and upper secondary school. A qualitative thematical analysis was performed, and two educational resources developed to support how to use education in achieving SDGs were used as a guiding framework. The findings show eight learning outcomes (<2%) explicitly related to sustainable development perspectives. We found these learning outcomes in courses dealing with outdoor education, movement and health didactics, and work environment and ergonomics. Our further analysis suggests that 37 learning objectives (19% as cognitive, 43% as socio-emotional, and 38% as behavioural) and 31 competencies (35% within knowledge and understanding, 32% within skills and applications, and 32% within values and attributes) could be linked to our themes of learning outcomes. These learning objectives and competencies of the SDGs were for good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, reduced inequalities, peace, justice, and strong institutions. The main findings signal a possibility to work with the conceptualisation of sustainable development perspectives and SDGs in PETE. PETE educators should be encouraged to critically reflect on what it can mean to include sustainable development perspectives in PETE course syllabi.

1. Introduction

In this day and age, humanity faces several global challenges, such as poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice. These global challenges are the points of departure in the 2030 Agenda that were introduced by the United Nation in 2015 [1]. The 2030 Agenda is a universal call to action for people, the planet, and prosperity. Based on global solidarity, the 2030 Agenda calls for all countries, developed and developing alike, and stakeholders to implement the action plan [1].

In relation to the 2030 Agenda, education has been acknowledged as one main driver to realise the 17 SDGs [2]. Here, the concept of education for sustainable development is introduced, which according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), aims at “encouraging the transformation of education so that it is able to contribute effectively to the reorientation of societies towards sustainable development” [3]. It has been suggested that education for sustainable development should build on quality education that addresses deep and enduring social and cultural changes [4].

Moreover, education is not only addressed directly as a goal (SDG #4) but may also contribute to the sustainability challenges by empowering people to make responsible decisions. This requires sustainability competences, such as systems thinking, future oriented thinking, collaboration, strategic thinking, critical thinking, self-awareness, emotional intelligence, the ability to use media, and integrated problem solving [5]. These sustainability competences may be developed through appropriately designed pedagogies that engage heads (cognitive domain), hands (psychomotor domain), and hearts (affective domain) [2,5].

The broad and ambitious 2030 Agenda encompass 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) that are divided into 169 targets (Figure 1). The 17 SDGs cover economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. In essence, the far-reaching SDGs are expected to stimulate actions to enable people to fulfil their potential in a healthy environment, ensure sustainable consumption and production to meet the needs of the present and future generations, ensure that all human beings can enjoy prosperity, and foster peaceful, just, and inclusive societies [1].

Figure 1.

The 17 sustainable development goals.

In addition to education, it has been acknowledged that physical activity and sport may contribute to the realisation of the vision set out by the 2030 Agenda [6,7]. For example, links have been found between physical activity and 15 of the 17 SDGs, with robust evidence for the five SDGs: good health and well-being (#3), industry, innovation, and infrastructure (#9), sustainable cities and communities (#11), climate action (#13), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16) [8]. Since education, physical activity, and sport have been acknowledged as contributors, physical education has both the potential and an obligation to contribute to the visions set out by the 2030 Agenda.

As a compulsory part of the school curriculum in most countries, physical education provides opportunities for students to engage in physical activity, develop movement capability and sport-related skills, and learn about health and healthy lifestyles [9]. In physical education, students can experience positive social interactions, develop cooperating skills, and demonstrate empathy and respect [10,11,12]. Despite this, several issues have been debated in physical education over recent decades. From an international perspective, these critical issues include, for example, the dominance of the biomedical perspective on health, the multi-activity-based curriculum with ambiguous learning goals and a narrow view of the concept of abilities, and the noninclusive teaching and learning environment [13,14,15]. More specifically, studies have shown that physical education teachers consider promotion of physical activity as their primary objective [16]. Physical education may also follow conventional sport logic, which is more reminiscent of recreation than an environment for learning [17], and students often seem unaware of what they are expected to learn [18]. We argue that these issues are problematic in relation to not only quality physical education but also SDGs, such as quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), and reducing inequality (#10).

These critical issues aside, there has recently been a growing interest in exploring and establishing links between physical education and sustainable development perspectives. This includes interest towards environmental attunement [19], sustainable development perspectives in general [20], and links between physical education, the 2030 Agenda, and the SDGs [21,22,23]. For example, Lohmann et al. found that, although not explicitly linking them to the concept of education for sustainable development, different content and methods of education for sustainable development may already be implemented and discussed in the field of physical education [20]. Some of the sustainable development competencies related to the sport and movement aspects of professional knowledge, beliefs and values, motivational orientations, and self-regulations include knowledge of challenges and problems of sustainable development in the sport context, knowledge about ethical and value discourses, and critical thinking [20]. In relation to the 2030 Agenda, it has been suggested that 24 of the 169 targets could be addressed in physical education, including targets from SDGs such as good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), reduced inequalities (#10), and climate action (#13) [22]. Consequently, there may be links between physical education and the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development [23].

Moreover, several well-known established practice-based models in physical education, including the personal and social responsibility model and the cooperative learning model, may facilitate sustainable development competencies [22,23]. Nonetheless, while there may be links to sustainable development perspectives, it is also essential to recognise that any aspirations towards integrating SDG-oriented content in physical education should be conducted without overlooking core aims of the subject, such as learning about physical activity, health, and healthy lifestyles [20,23]. Since the actual SDG-oriented teaching content therefore may not be comprehensive, it may be critical to approach teaching in a manner that promotes sustainable attitudes among students. As recently stated by Baena-Morales et al. [23] (p. 13): “It is not teaching a sport, and it is doing it with recycled material; the aim is to educate attitudes so that students understand and begin to develop competencies that are conducive to a more sustainable world. Educate in the values of reusing materials and objectives in order to educate towards more sustainable consumption. It is not an orienteering race; it is an opportunity to respect and enjoy nature. It is not a group activity but a way to develop employability attitudes. We must understand our subject not as an end in itself but as a means to help create a more prosperous and sustainable world”. In this sense, sustainable development perspectives may be interpreted as an overarching teaching approach rather than another addition of teaching content to a sometimes already overcrowded physical education curriculum [20].

The Present Study

Acknowledging education as critical to realising the SDGs means that teachers in primary and secondary school may play a critical role. Teachers are positioned at the heart of the microlevel in education as those being responsible for educating future generations to address the global challenges that humanity is facing [24]. Despite this, awareness in sustainable development among physical education teachers it is not well understood. One study has found that physical education teachers had an overall high consciousness for sustainable development but that awareness in sustainability generally is higher among females compared with male physical education teachers [25]. Furthermore, we argue that, if any changes in relation to education for sustainable development are to take place in school, teacher education is one critical point of departure. This is because teacher education should contribute to the development of knowledge, skills, and abilities needed for tomorrow’s teachers to become active change agents to bring about change to the school curriculum.

The previous literature on teacher education suggests that sustainable development education is generally embedded by teacher educators as a component of a compulsory subject, or as an essential part of school policies, practices, and activities [26,27,28]. In relation to physical education teacher education (PETE), little attention has been directed towards sustainable development perspectives and sustainable development competencies. At least in part, this may be explained by the fact that physical education cultures, norms, and values that generally do not include sustainable development perspectives, may be taken for granted and seldom challenged in PETE. To date, some critical competencies among physical education teachers include being able to perform different types of activities with the correct technique, have knowledge about tactics and rules, and to detect errors and design task progressions, as well as select and modify appropriate tasks and provide appropriate feedback [29]. From a public health perspective, it has also been recommended that physical education teachers are competent in areas such as physical inactivity, health, and fitness testing [30]. In line with this, a study from Sweden showed that mechanistic views of physical activity, rather than social perspectives on health and critical inquiry, dominate course syllabi in PETE [31]. However, the need for alterative perspectives in PETE has been discussed, including the necessity to identify novel integrative approaches to movement cultures and issues related to social justice education and inclusion, among others [29,32,33].

Even though physical education has the potential to contribute to the visions set out by the 2030 Agenda, little attention has been directed towards sustainable development perspectives in PETE [20,21,22,23]. More research is needed to understand how sustainability can be understood, framed, and integrated in PETE. As it constitutes a critical source of information regarding what physical education teacher students should know, understand, and/or be able to perform by the end of a course, we believe that one way to gain such an understanding is to analyse the current state of PETE course syllabi. In this explorative paper, we aimed to investigate how sustainable development perspectives are reflected in PETE course syllabi. In doing so, we focus on the learning outcomes. Our paper was guided by the following two research questions:

- What learning outcomes in PETE course syllabi are explicitly related to sustainable development perspectives?

- What learning outcomes in PETE course syllabi can be linked to SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies?

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Source of Data

The source of data for this paper was PETE course syllabi from higher education institutions that prepare physical education teachers to teach pupils in compulsory school (grades 7−9) and upper secondary schools in Sweden. Course syllabi are generally designed by PETE educators as those responsible for the course, and then authorised by the faculty board at each higher education institution. Course syllabi encompass a description of the course contents, form(s) of teaching, learning outcomes, and assessment formats. Some previous studies with focus on PETE have used course syllabi as the source of data [31,34]. The learning outcomes outlined in the course syllabi was the subject for analysis as they govern the knowledge, understanding, skills, and values (often divided into three types of learning outcomes: knowledge and understanding; competence and skills; and judgement and approach) that students need to demonstrate to pass a course. Through websites, we located and retrieved all physical-education-specific course syllabi from the eight Swedish higher education institutions which offer physical education as a first subject in compulsory school (grades 7−9) and/or upper secondary school. In doing so, we retrieved the latest version of the physical-education-specific course syllabi available (i.e., at least one subcourse with focus on physical education) and excluded the courses that focused on teaching practice (in-service training), methodology, and degree projects. In total, this resulted in 42 physical-education-specific course syllabi (the courses ranged from 7.5 HECs to 30 HECs per course) with a median of 4.5 (range: 3−9) courses per institutions. Of these, 5 courses were exclusively directed towards compulsory school (grades 7−9), 24 towards upper secondary school, and 13 were combined. Together, these course syllabi covered 557 learning outcomes.

2.2. Guiding Framework

For the aim of this paper, we used two reports as a guiding framework. These two reports are educational resources developed to support policymakers, curriculum developers, and educators on how to use education in achieving the SDGs. The two reports, which are further described below, are (i) the Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives (EfSDG-LO) from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and (ii) the Curriculum framework for the Sustainable Development Goals (CF-SDGs) from Commonwealth [35,36].

2.2.1. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives

The EfSDG-LO report from UNESCO provides suggestions on SDG-oriented learning objectives [35]. These SDG-oriented learning objectives are outlined on a general level, aiming at providing students with future capabilities. Furthermore, they can be tailored for any specific learning settings and sociocultural context. Educators and curriculum developers must define the level to be achieved by their learners, ranging from basic in primary education to expertise in higher education.

For each SDG, there are cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioural learning objectives. These learning objectives include knowledge and skills that are needed to understand the SDGs (cognitive) and social and self-reflection skills that enable learners to, for example, collaborate, communicate, and develop themselves (socio-emotional), as well as action competencies (behavioural). Table 1 provides examples of learning objectives for the SDG good health and well-being (#3), stratified across the cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioural learning objectives.

Table 1.

Examples of learning objectives for the SDG good health and well-being (#3) available in EfSDG-LO from UNESCO [35]. All learning objectives as quotes from UNESCO [35], page 16.

2.2.2. Curriculum Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals

The CF-SDGs report aims to support those involved in planning and delivering education and learning to bring about the transformational changes and competencies needed for people to lead fulfilling lives [36]. It embraces a holistic life-course approach, involving education from early childhood to adulthood, to reinforce the need for lifelong learning and for all to participate in realizing the SDGs.

As part of the life-course approach, the CF-SDGs report provides suggestions on SDG-oriented learning outcomes for all education levels, including higher education, divided into three sets of competencies. These three sets of competencies are knowledge and understanding, skills and applications, and values and attitudes. Competencies for knowledge and understanding cover, for example, life skills and an understanding of and how to respond to social, environmental, and economic challenges and complexities. Among others, competencies for skills and applications cover critical thinking, problem-solving, and goal-setting skills. Competencies for values and attitudes cover, for example, commitment to justice and respect for diversity. Table 2 provides examples of competencies for the SDG good health and well-being (#3).

Table 2.

Examples of competencies for the SDG good health and well-being (#3) available in CF-SDGs from Commonwealth [36]. All competencies as quotes from Commonwealth [36], page 26.

2.3. Qualitative Analysis

Before the qualitative analysis was conducted, we extracted all learning outcomes from the physical-education-specific course syllabi to an external text sheet (Word document) developed for this paper. We then checked the external text sheet and any duplicates were removed, leaving 496 unique learning outcomes. We then conducted our qualitative analysis in two steps.

2.3.1. The First Step of the Analysis

In the first step of our qualitative analysis, we searched the external text sheet for learning outcomes that explicitly relate to sustainable development. This meant that we searched for the learning outcomes that contain the words (in Swedish) “sustainable” (hållbar), “sustainability” (hållbarhet), “sustainability perspectives” (hållbarhets perspektiv), and “sustainable development” (hållbar utveckling). Thereafter, we highlighted the learning outcomes that explicitly relate to sustainable development and then extracted them to another table. Then, we sorted the learning outcomes into types of courses that reflect the focus area.

2.3.2. The Second Step of the Analysis

As frequently used in qualitative sport and exercise research, the second step of our qualitative analysis involved a thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is used to identify and analyse patterns within data, such as written text, and require flexibility to fit the data and the research questions [37,38,39]. Here, the researchers themselves become a critical instrument in the analytical procedure and should therefore undertake a reflective and thoughtful engagement with the data. As two researchers were involved, the analytical procedure was a collaborative approach that allowed for a nuanced reading and interpretation of the data.

We argue that the thematic analysis aligned well with the explorative approach of this paper, as it involved a more generous reading of the learning outcomes. In practice, this allowed us to conduct an analysis beyond what was explicitly related to sustainable development. This was achieved by first using thematic analysis to generate (or produce) themes of learning outcomes and then linking SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies to the themes.

We conducted our thematic analysis in six steps with references to the previous literature on thematic analyses [37,38,39]. This included (i) familiarization with data, (ii) generating codes, (iii) generating themes, (iv) reviewing themes, (v) defining and labelling themes, and (vi) producing the paper. First, we familiarised ourselves with the guiding framework and the suggested SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies. We then read the extracted learning outcomes multiple times to obtain an initial sense of the content. Here, we also took notes and marked initial ideas for the analysis. Next, we used a classification scheme to create order in the large number of learning outcomes. We read the extracted learning outcomes in depth and generated codes. Then, we collected the codes to generate tentative themes (and subthemes) of learning outcomes. The themes were identified at a semantic level but consideration was also given to latent concepts. Although we did not use a predetermined coding protocol, the initial ideas for the analysis (as noted above) served as inspiration during the process of generating themes. Then, we reviewed and revised the tentative themes several times until a final set was decided on, defined, and labelled. Descriptions of the final set of the eight themes of learning outcomes that were generated from our analysis are available in Table 3.

Table 3.

The final set of themes of learning outcomes that was generated from our analysis with descriptions.

After the thematic analysis, we searched for SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies that could be linked to our themes of learning outcomes. In doing so, our analysis was conducted at a latent level that allowed us to go beyond the semantic content of the data. Moreover, we used a back-and-forth process that allowed us to move between the guiding framework and our themes of learning outcomes. The links that we found between the guiding frameworks and our themes of learning outcomes were also reviewed and revised several times until we decided on the final set of analysis that linked SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies to our themes of learning outcomes.

In the section below, we present and discuss our findings. Examples of learning outcomes were translated from Swedish into English.

3. Findings

3.1. Learning Outcomes That Explicitly Relate to Sustainable Development Perspectives

In the first step of our analysis, we found eight learning outcomes that explicitly relate to sustainable development perspectives. These eight learning outcomes accounted for fewer than two percent of the total number of retrieved learning outcomes. Moreover, these learning outcomes were identified in four of the eight considered higher education institutions.

In our analysis, we considered these learning outcomes to be found in courses (courses or subcourses) as presented in Table 4. The first type of course was outdoor education. This type of course involved learning outcomes that related outdoor education to sustainable development perspectives. In the second type of course, the focus was on the importance of movement capability for health from a sustainability perspective. We labelled this course as Movement and health didactics. Finally, we labelled the third type of course as Work environment and ergonomics.

Table 4.

Type of courses (focus area) and learning outcomes that explicitly relate to sustainable development perspectives.

We conclude that words such as “sustainable”, “sustainability”, “sustainability perspectives”, and “sustainable development” seldom appear explicitly in the learning outcomes. This does not, however, necessarily mean that sustainable development perspectives are not addressed in the physical education courses. In many ways, sustainable development perspectives should permeate all teaching and not serve as an additional layer of learning objectives and competencies to be added to course syllabi that may already be overloaded.

In the section below, we present the second step of our analysis that involved a more generous reading of the learning outcomes. Here, we looked beyond what was explicitly related to sustainable development perspectives, and our analysis involved SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies that could be linked to our final set of themes of learning outcomes.

3.2. Sustainable Development Goals Oriented Learning Objectives and Competencies

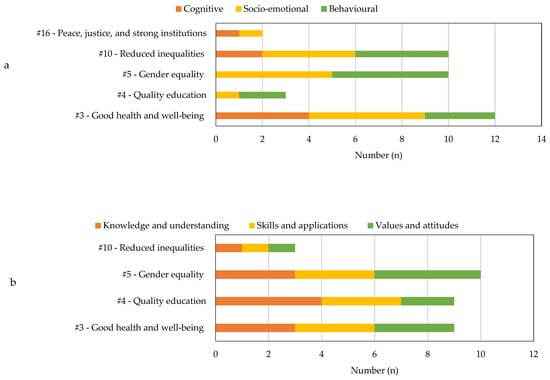

When we used the EfSDG-LO from UNESCO, we found that 37 learning objectives could be linked to our themes of learning outcomes. These learning objectives were for the SDGs good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), reduced inequalities (#10), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16). Of these learning objectives, 19% could be placed as cognitive, 43% as socio-emotional, and 38% as behavioural learning objectives.

When we used the CF-SDGs from Commonwealth, we found that 31 competencies could be linked to our themes of learning outcomes. These competencies were for the SDGs good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), and reduced inequalities (#10). Of these competencies, 35% could be placed within knowledge and understanding, 32% within skills and applications, and 32% within values and attributes.

In Figure 2, we illustrate the distribution of these SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies across the SDGs. We also provide examples of SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies that could be linked to our different themes of learning outcomes in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Distribution (n) of the SDG-oriented learning objectives (a) and competencies (b) across the SDGs.

Table 5.

SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies (from the guiding frameworks) that could be linked to the different themes of learning outcomes (from physical education specific courses). Examples of learning outcomes from the physical education-specific courses are presented in the last column.

4. Discussion

The aim of this explorative paper was to investigate how sustainable development perspectives are reflected in PETE course syllabi, focusing on the learning outcomes. We did not expect that the learning outcomes from the retrieved physical education specific courses would address all the SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies as specified in the educational resources EfSDG−LO and CF−SDGs [35,36]. In line with this, the main finding from our second step of the analysis was that learning objectives and competencies for the SDGs good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), reduced inequalities (#10), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16) could be linked to our themes of learning outcomes. The three dimensions of economic, social, and environmental sustainable development were represented. In addition, we found that all dimensions of learning objectives (i.e., cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioural) and competencies (i.e., knowledge and understanding, skills and applications, and values and attributes) were represented, although to varying degrees.

In terms of research studies, physical education has mainly been discussed in relation to the SDGs good health and well-being (#3) and quality education (#4) [21]. However, in their review, Baena-Morales et al. suggested that targets from the following eight SDGs could be worked on in physical education: good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), gender equality (#5), decent work and economic growth (#8), reduced inequalities (#10), responsible consumption and production (#12), climate action (#13), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16) [22]. Comparing the main finding from our second step of the analysis with those from these two previous reviews, we found both similarities and differences in terms of contribution to specific SDGs. In a broad sense, however, it seems that the contribution of physical education and PETE, at least from what we currently know, may be the most prominent for the SDGs good health and well-being (#3), quality education (#4), and gender equality (#5).In line with the above, most of the learning objectives and competencies that we could link to our themes of learning outcomes were for the SDG good health and well-being (#3). These themes of learning outcomes included Health-related areas and issues, Movement activities, Motivation, Norms, Inclusion, and Safety issues. On the contrary, we found that relatively few learning objectives and competencies for the SDG quality education (#4) could be linked to our theme of learning outcomes Teaching, didactics, and professionalism. At first, this may be unexpected since the SDG quality education (#4) may be highly related to the concept of quality physical education. However, most of the learning objectives and competencies for the SDG quality education (#4) concern perspectives related to education for sustainable development [35,36], and these types of learning outcomes were not represented in the theme Teaching, didactics, and professionalism. It should be acknowledged, however, that many of the learning objectives and competencies for the SDG good health and well-being (#3) reflect what one may expect a professional physical education teacher to know, understand, and/or be able to perform. To be knowledgeable in health-related issues and areas, be able to perform, or at least describe how to perform, various movement activities with safety in mind, and be able to critically relate to and create favourable conditions for inclusive teaching and learning environments, may be considered as necessary qualifications for teachers who deliver quality physical education. We argue, therefore, that the links between our themes of learning outcomes and the SDG quality education (#4) may be more prominent than what our analysis shows. This may also be the consequence of our decision to use the two educational resources EfSDG-LO and CF-SDGs as guiding frameworks when conducting our second step of the analysis.

In relation to the two SDGs gender equality (#5) and reduced inequalities (#10), several learning objectives and competencies that focus on gender perspectives and inequalities could be linked to the themes of learning outcomes Sex and gender and Inclusion. It should also be noted that learning objectives for the SDG peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16) could be linked to the themes of learning outcomes Inclusion. Contemporary physical education seems to be characterised by a noninclusive teaching and learning environment [14]. Among others, gender, sexuality, disability, social class, and ethnicity may be critical factors related to opportunities to be recognised in physical education [14]. Issues related to sex, gender, and inclusion, which according to our analysis have received attention in PETE, are central to the two SDGs gender equality (#5) and reduced inequalities (#10). The importance of ensuring an inclusive, child-centred approach to physical education is also highlighted in the guidelines for quality physical education [40].

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have explored sustainable development perspectives in PETE. However, one study provided insights to a cross-sector partnerships programme to implement the SDGs good health and well-being (#3) and quality education (#4) by improving PETE through stronger partnerships between schools and universities, as well as a greater integration of theory and practice [41]. The dearth of studies, along with the main findings from the present paper, signal a possibility to work with the conceptualisation of sustainable development perspectives and the SDGs in PETE. As previously noted, researchers have recently begun exploring and establishing links between physical education sustainable development perspectives, including specific links to the 2030 Agenda [20,21,22,23]. As a response to the 2030 Agenda, as well as the criticism of contemporary physical education, we have recently suggested three steps for opening a process that can deepen our conversations and strengthen our actions in relation to education for sustainable development in physical education. These three steps include curricula revisions, a reorientation of learning perspectives, and a rethinking of perspectives on health and well-being [42]. From our point of view, PETE educators should also be encouraged to critically reflect on what it can mean to include sustainable development perspectives in PETE course syllabi. This may be one way to challenge existing cultures and practices and allow for a re-thinking and re-orientation of PETE teaching and learning practices. In this context, it should be stressed that the concept of sustainability may involve a number of ontological and epistemological layers that generate critical questions, such as what is to be sustained, for whom, and by whom. PETE educators should therefore also reflect on how sustainable development perspectives can be connected to educational theories [42]. As previously suggested, one learning perspective that may be suitable in relation to education for sustainable development perspectives is that of transformative learning [2,4].

Moreover, while sustainable development perspectives may allow for a re-thinking and re-orientation of PETE teaching and learning practices, integrating SDG-oriented content should be conducted without overlooking the core aims of physical education [20,23]. In this regard, some questions that could be addressed may be how the concept of sustainable health and well-being can be explored, challenged, and applied in the students’ everyday life. From our point of view, such a concept embraces a holistic perspective that involves knowledge and understanding of the relationship and interplay between health and the environment. Furthermore, it means embracing a holistic, lifelong approach to movement activities and physical activity that goes beyond what takes place in physical education. Another question is to what extent environmental issues in relation to physical activity should be considered. In their global action plan, the World Health Organisation suggests several direct and indirect pathways that may link physical activity policies to many of the SDGs [6]. For example, the implication of physical activity in relation to the SDG good health and well-being (#3) goes beyond the prevention and treatment of noncommunicable diseases. Encouraging active transportation, such as walking and cycling, may reduce traffic volumes, reduce road traffic accidents, and even improve air quality, as well as contribute to health and well-being [43,44]. Physical activities carried out in nature also contribute to an appreciation of and desire for green environments such as parks, as well as health and well-being [45]. Improved transport infrastructure that promotes physical activity, such as walking and cycling, may reduce automobile use and, thereby, not only less use of fossil fuels and emissions, but also everyday life physical activity. If the latter part of lifelong learning is considered, then sustainable cities and communities (#11), and perhaps also responsible consumption and production (#12) and climate action (#13), would be included in the SDGs that physical education and PETE could elaborate upon.

In terms of future research, the next step may be to conduct a similar analysis of learning outcomes in other countries. This would enable cross-country comparisons that may generate important insights and lessons learned that can be used to initiate discussions regarding how sustainable development perspectives could be introduced or strengthened in PETE.

Moreover, we chose to focus on the learning outcomes as retrieved from physical-education-specific course syllabi. We conducted our research this way because learning outcomes are critical sources of information regarding what students should know, understand, and/or be able to perform by the end of the course. As such, learning outcomes logically reflect beliefs, values, and attitudes that PETE educators wish future physical education teachers acquire. Nonetheless, learning outcomes are not addressed and realised in isolation, and simply analysing learning outcomes may introduce bias due to decontextualization since we do not know what takes place in the actual teaching situation. In relation to education for sustainable development, pedagogies should engage heads (cognitive domain), hands (psychomotor domain), and hearts (affective domain) [2,5], and such approaches may include learner-centred, action-oriented, and transformative learning [35]. Another suggestion for future research is therefore to explore how sustainable development perspectives may appear in the actual teaching situation. This could, for example, be explored through focus group interviews with PETE educators.

This study is not without its limitations. As discussed above, one limitation is that we chose to focus only on learning outcomes. We can therefore not comment on whether sustainable development perspectives may appear in the actual teaching situation. It should, furthermore, be stressed that while the EfSDG-LO and CF-SDGs, the guiding frameworks, suggest SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies, they are not exhaustive or definitive [35,36]. Although we found these two educational resources suitable for use in exploring complex and comprehensive areas such as sustainable development perspectives and the 2030 Agenda, this should be considered when interpreting the findings of our study. Furthermore, it has been proposed that studies should explore the contribution to the 2030 Agenda by explicitly stating links to specific targets that compose the SDG, rather than merely stating the specific SDG [23]. However, this was not possible in the present paper as the two educational resources only linked SDG-oriented learning objectives and competencies to specific SDGs [35,36]. Despite this, we can observe links between the themes of learning outcomes and, for example, the SDGs good health and well-being (#3) target 4 (reducing premature mortality and promoting mental health and wellbeing), quality education (#4) target 5 (reduction of gender disparities in education and equality of vulnerable people), reduced inequalities (#10) targets 2 (social, economic and political inclusion of all people), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (#16) target 7 (ensure inclusive, participatory and representative decisions that respond to the needs).

5. Conclusions

In this explorative paper, we focused on how sustainable development perspectives are reflected in PETE course syllabi. Fewer than two percent of the analysed learning outcomes explicitly related to sustainable development perspectives. These learning outcomes were found in courses dealing with outdoor education, movement and health didactics, and work environment and ergonomics. Our further analysis suggests that learning objectives and competencies for 5 of the 17 SDGs could be linked to different themes of learning outcomes. The main findings from this paper signal a possibility to work with the conceptualisation of sustainable development perspectives and the SDGs in PETE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and S.L.; methodology, A.F. and S.L.; formal analysis, A.F. and S.L.; investigation, A.F. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.; writing—review and editing, A.F. and S.L.; visualization, A.F.; project administration, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Laurie, R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; McKeown, R.; Hopkins, C. Contributions of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to Quality Education: A Synthesis of Research. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaping the Future We Want—UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (Final Report). Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=1682&menu=35 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Boström, M.; Andersson, E.; Berg, M.; Gustafsson, K.; Gustavsson, E.; Hysing, E.; Lidskog, R.; Löfmarck, E.; Ojala, M.; Olsson, J.; et al. Conditions for Transformative Learning for Sustainable Development: A Theoretical Review and Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for A Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Commonwealth. Sport for Development and Peace and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://climate.thecommonwealth.org/our-work/sport-development-and-peace (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical Activity Promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building Synergies to Maximize Impact. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardman, K.; Murphy, C.; Routen, A.C.; Tones, S. World-Wide Survey of School Physical Education: Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beni, S.; Fletcher, T.; Ní Chróinín, D. Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature. Quest 2017, 69, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bailey, R.; Armour, K.; Kirk, D.; Jess, M.; Pickup, I.; Sandford, R.; Education, B.P. The educational Benefits Claimed for Physical Education and School Sport: An Academic Review. Res. Pap. Educ. 2009, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K.; Chapelle, L.; Prins, F.J.; De Meester, A.; Haerens, L.; van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Personal and Social Development in Physical Education and Sports: A Review Study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2010, 26, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mong, H.H.; Standal, Ø.F. Didactics of Health in Physical Education—A Review of Literature. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabaskues-Lasheras, I.; Usabiaga, O.; Lozano-Sufrategui, L.; Drew, K.J.; Standal, Ø.F. Sociocultural Processes of Ability in Physical Education and Physical Education Teacher Education: A Systematic Review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 26, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penney, D.; Jeanes, R.; O’Connor, J.; Alfrey, L. Re-Theorising Inclusion and Reframing Inclusive Practice in Physical Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsson, H.; Nyberg, G. ‘It Doesn’t Matter How They Move Really, as Long as They Move.’ Physical Education Teachers on Developing Their Students’ Movement Capabilities. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.; Karlefors, I. Physical Education Cultures in Sweden: Fitness, Sports, Dancing … Learning? Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redelius, K.; Quennerstedt, M.; Öhman, M. Communicating Aims and Learning Goals in Physical Education: Part of a Subject for Learning? Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, R.; Taylor, N.; Gard, M. Environmental Attunement in Health, Sport and Physical Education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, J.; Breithecker, J.; Ohl, U.; Gieß-Stüber, P.; Brandl-Bredenbeck, H.P. Teachers’ Professional Action Competence in Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review from the Perspective of Physical Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröberg, A.; Lundvall, S. The Distinct Role of Physical Education in the Context of Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals: An Explorative Review and Suggestions for Future Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Martínez-Martínez, J. Sustainable Development Goals and Physical Education. A Proposal for Practice-Based Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; González-Víllora, S. Physical Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Reflections and Comments for Contribution in the Educational Framework. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeren, E. Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “Quality Education” from Micro, Meso and Macro Perspectives. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A.; Campillo-Sánchez, J.; González-Víllora, S. Sustainability Awareness of In-Service Physical Education Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Ferreira, J.-A. What Does the Research Evidence Base Tell Us About the Use and Impact of Sustainability Pedagogies in Initial Teacher Education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Stevenson, R.B.; Lasen, M.; Ferreira, J.-A.; Davis, J. Approaches to Embedding Sustainability in Teacher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bürgener, L.; Barth, M. Sustainability Competencies in Teacher Education: Making Teacher Education Count in Everyday School Practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, E.; Barker, D.M. Re-Thinking Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Physical Education Teachers—Implications for Physical Education Teacher Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Webster, L.; Russ, L.; Molina, S.; Lee, H.; Cribbs, J. A Systematic Review of Public Health-Aligned Recommendations for Preparing Physical Education Teacher Candidates. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2015, 86, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, E.; Larsson, H. What Should a Physical Education Teacher Know? An Analysis of Learning Outcomes for Future Physical Education Teachers in Sweden. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton-Fisette, J.L.; Sutherland, S. Moving Forward with Social Justice Education in Physical Education Teacher Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, W. Inclusive and Accessible Physical Education: Rethinking Ability and Disability in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Lee, Y.S.; Ward, P.; Li, W. A Critical Examination of Movement Content Knowledge Courses in Physical Education Teacher Education Programs. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2015, 34, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Commonwealth. A Curriculum Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, N.; Thompson, J. Quality Physical Education (QPE): Guidelines for Policy Makers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, T. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Promoting Health and Well-Being through Physical Education Partnerships. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1188469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundvall, S.; Fröberg, A. From Individual to Lifelong Environmental Processes: Reframing Health in Physical Education with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Exploring Bikeability in a Metropolitan Setting: Stimulating and Hindering Factors in Commuting Route Environments. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Exploring Bikeability in a Suburban Metropolitan Area Using the Active Commuting Route Environment Scale (ACRES). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 8276–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces and Health; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).