Abstract

An increasing number of academic institutions offer their staff the option to work from other places than the conventional office, i.e., telework. Academic teaching and research staff are recognized as some of the most frequent teleworkers, and this seems to affect their well-being, work performance, and recovery in different ways. This study aimed to investigate academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework within the academic context. For this, we interviewed 26 academics from different Swedish universities. Interviews were analyzed with a phenomenographic approach, which showed that telework was perceived as a natural part of academic work and a necessary resource for coping with, and recovering from, high work demands. Telework was mostly self-regulated but the opportunity could be determined by work tasks, professional culture, and management. Telework could facilitate the individual’s work but could contribute to challenges for the workgroup. Formal regulations of telework were considered a threat to academics’ work autonomy and to their possibility to cope with the high work demands. The findings provide insight into academics’ working conditions during teleworking, which may be important for maintaining a sustainable work environment when academic institutions offer telework options.

Keywords:

telework; academics; autonomy; working conditions; well-being; experiences; interviews; occupational health 1. Introduction

The development and use of information and communication technologies (ICT) enable work beyond the conventional physical and temporal office premises, which has given rise to flexible work arrangements such as telework. On a societal level, telework is seen to contribute to environmental and social sustainability by providing the opportunity to reduce work commuting and traffic emissions while also increasing accessibility in working life [1,2]. A growing number of employers offer telework as an alternative to traditional office work, hoping it will reduce workspace costs and improve organizational productivity and the work environment [2]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of teleworkers in working life increased rapidly, and it is assumed that the high prevalence of teleworkers will persist after the pandemic diminishes [3]. This presumed “new normal” work situation has prompted employers to request more knowledge on the opportunities and challenges with telework options for organizational performance and work environment. Several studies show that the enabling of flexibility in time and space through teleworking may facilitate staffs’ adaption of work to private and professional needs and improve their autonomy, well-being, job engagement, and work performance [4,5,6,7]. However, the increased implementation of telework options in working life has raised employers’ concern about possible negative impacts on work efficiency and work relations. Above all, social and professional isolation and work-life conflicts are often mentioned as potential consequences of telework that could decrease work satisfaction, well-being, and organizational work performance [8,9,10]. According to boundary theories, the integration of work and nonwork may challenge teleworkers’ ability to distinguish between their private and professional roles. This might cause inter-role conflict, which could hamper teleworkers’ mental detachment and recovery from work after teleworking hours [11]. Further, from a socio-technical perspective, insufficient organizational resources, such as managerial and technical support could hinder teleworkers’ insight and participation in work processes, and lead to feelings of social exclusion [12].

Telework options are predominantly offered in so-called knowledge and information organizations (e.g., IT, finance, education, science) including professions with work tasks that involve “…to acquire, create and apply knowledge in purpose of their work” [4], normally enabled through the use of ICTs [2,4,5]. Among these professions, academic teaching and research staff are recognized as some of the most frequent teleworkers [1,2]. In 2019, approximately 40 percent of the teleworkers in European Union countries belonged to the teaching and science professions [2]. This has partly been explained by the academics’ autonomous and flexible work characteristics, which are considered to facilitate telework [2,13,14]. However, the high prevalence of telework in academia has also been explained by increasing demands in teaching and research, forced by e.g., globalization [15,16,17,18]. The work situation in academic institutions is generally described as stressful because of the heavy workload, time pressure, competition for research grants and temporary positions, and it is shown that lack of sufficient job resources (e.g., financing, personnel) renders difficulties in coping with the situation [15,18,19]. Studies on Swedish academic institutions show that this strenuous work situation leads to extended worktime and sickness-presenteeism, which may affect academics’ work performance and well-being negatively [18,20].

The research on telework in academic institutions is limited, but similar to what is found in studies on other knowledge and information organizations, teleworking seems to affect academics privately and professionally in different ways. Among other things, telework is reported to increase, as well as decrease, academics’ job satisfaction, work performance, recovery, work-life balance, well-being, and stress [13,14,17,21,22]. Therefore, to maintain a sustainable work environment in academic institutions it is important to clarify the opportunities and challenges telework options imply for academics’ work performance and health.

The previous research on telework highlights a complexity regarding the impact telework has on organizational, professional, and health-related aspects. For example, the effect of telework on health-related outcomes depends on factors such as work autonomy [4,5,8,9]. In general, research has focused on the effects of telework on individual work-related aspects, such as job satisfaction. This approach has been criticized for lacking consideration for the organizational aspects of telework options (e.g., work culture, type of work tasks) [1,4,5,8]. A systematic review on telework and well-being showed that the majority of the research was based on quantitative findings and therefore, it has been suggested to perform studies with qualitative design in order to deepen the understanding of telework outcomes [4,5].

To achieve WHOs eighth sustainability development goal for “decent work and economic growth” [23], it is important to gain knowledge relevant to the expected increase of telework in working life. It is argued that studies should consider telework as an occasional, rather than full-time work practice to understand the future outcomes for regular teleworkers [2,4,5,8,9]. This motivates studies on experienced teleworkers who alternate telework with work from the conventional office. Hence, the context of higher education with its high prevalence of telework may serve as an example. Considering academics’ demanding work situation, and its potential consequences for work performance and well-being, knowledge from this context may also be important for understanding how telework policies can influence the quality of teaching and research in higher education. This may ultimately promote sustainable working conditions for telework practice in academic institutions. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework in academic institutions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted interviews and analysis with an inductive phenomenographic research approach. It relies on the second-order perspective where the aim is to portray the qualitative differences in individuals’ lived experiences of a specific phenomenon [24]. In contrast to other qualitative approaches, such as phenomenology [25], the purpose of the phenomenographic analysis is thus not to capture the essence of individuals’ lived experiences of a specific phenomenon, but to illustrate the nuances within these experiences [24]. Phenomenographic research is considered complementary to other scientific methods as it can provide elaborated descriptions of how individuals experience a problem/phenomenon relative to a specific context [26]. The study design is approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Reg. no. 2018/399).

2.2. Informants

Eligible participants were employed at public Swedish universities as junior lecturers, senior lecturers, or professors, and engaged in teaching and/or research >50% of their working time. They had to practice telework regularly to some extent and to have done so for at least one year. The final sample consisted of 19 women and 7 men, aged between 34 and 68 years. The majority had children living at home. Among the informants, 9 were employed as junior lecturers and 17 as senior lecturers at public universities in different parts of Sweden. Among the senior lecturers, five were associate professors. The informants had worked at their current workplace for 1–28 years ( = 12 years) and the commuting time between their office premises and home varied between a few minutes to several hours. Two of the informants lived in other European countries than Sweden. The informants’ teleworking frequency ranged from a few hours per week to several weeks per month. They worked in the educational field of pedagogy, language, textile design, industrial technology, urban planning, history, environmental technology, religion, humanities, informatics, and health care. Their universities were of different sizes, some were more research-oriented, and some were more teaching-oriented.

2.3. Data Collection

The informants were strategically selected based on their age, gender, family situation, and academic position from a previous study sample where they had agreed to be contacted for future studies [22]. Candidate informants received email invitations with information about the study aim, procedure, and consent for participation. Reminders were sent out on two different occasions approximately two weeks apart. The interviews were then booked via email. Initially, the interview guide was tested in pilot interviews with four individuals who were representative of the population. Two interviews were held during a physical meeting, while two were held online using Zoom® video platform (Version 5.7.7). The pilot interviews were then evaluated and, when necessary, questions were clarified and revised. The final interview guide was semi-structured and contained 15 open-ended questions about the motives, practice, regulations, work environment, possibilities, and challenges of telework within the academic work context. There were also questions considering possibilities and challenges with working at the conventional office. Since there were no differences noted qualitatively between the physical and digital interview strategies, it was decided to perform the data collection digitally to increase the accessibility of informants. Before the interviews started, informants gave their consent to participate. During the interviews, informants were encouraged to speak freely about their experiences and perceptions, and follow-up questions were used to elaborate on their answers. All interviewees were asked to reflect on the same themes and questions. The interviewing stopped at 26 interviews, as saturation was reached, and no new information had emerged from the last five interviews [27,28]. The interviews lasted 13–42 min, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were held between April 2019 and March 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.4. Analysis

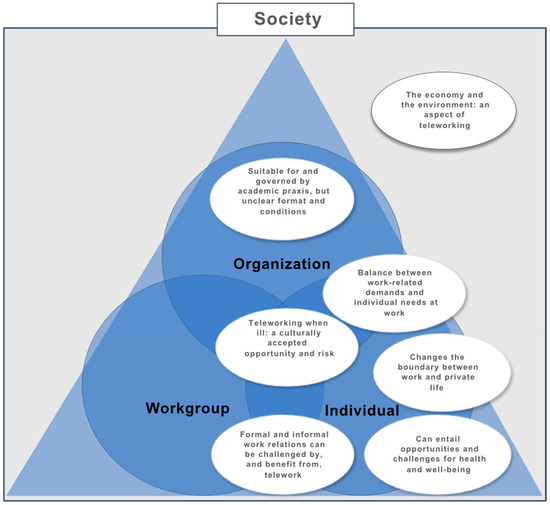

The analysis followed the seven steps for phenomenographical analysis described by e.g., Marton and Pong [24]. In accordance with these: in the first step, the interview transcriptions were read through several times to familiarize with the material, and to correct any errors that may have occurred in the transcription process. Secondly, phrases responding to the study aim were compiled from each interview and then, in the third step, each phrase was condensed into its central meaning in smaller text units. In the fourth step, text units with similar content were preliminarily grouped into categories. In the fifth step, the preliminary categories were compared to establish their qualitative differences and, if the content was too similar or vague compared to other categories, they were reconsidered. In the sixth step, the categories were given names that reflected the essence of their grouped conceptions. In the last, seventh step, when the categories were contrasted and compared, they were placed in the outcome space to depict the relations between them and also their relation to the context. The analysis resulted in seven categories representing the qualitatively different experiences and perceptions, and the nuances within them presented as sub-categories, of telework in the academic work context (Table 1). The categories constituted the outcome space illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Academics’ experiences of telework in academia: Main headings show the seven qualitatively different ways in which academics experience telework in academia, and sub-headings show the nuances within these experiences.

Figure 1.

The outcome space constituted by the seven categories of academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework in academia.

3. Results

This study aimed to investigate how academics experience and perceive telework within the academic context. For the informants, teleworking mainly entailed working from home but could also refer to working while commuting by train, plane, or bus, working from temporary accommodation, working while abroad on business trips, or working overtime at these locations. An overview of the identified main- and sub-categories is displayed in Table 1. In the text, citations from the interviewees are shown in italics.

3.1. Telework: Suitable for and Governed by Academic Praxis, but with Unclear Format and Conditions

This category describes how the option and choice of telework can be governed by organizational, societal, formal, and informal structures, and entails both advantages and disadvantages for academic work.

3.1.1. Choice of Telework Is Influenced by Academic Praxis and Culture, as Well as Personal Experience

Academic work can offer considerable freedom to independently choose where and when certain duties are performed, which was one reason that the choice of telework was viewed as natural and obvious. Previous experience of telework facilitated and contributed to the choice, while lack of experience and “technophobia” could contribute to the avoidance of telework. Some duties, such as business trips, (domestic and abroad), required teleworking. The work tasks could be important for the possibility to telework: research time provided freedom and flexibility that facilitated the choice of telework. Teaching, on the other hand, was affected by staff shortages and involved static planning and presence at the office that was perceived as complicating the choice.

And especially when you have research funding. If you have research funding, you have much more freedom to sit and write and things.Inf. 22.

Well, all I can say is that everyone says being a teacher is so flexible. My experience is just the opposite; my previous workplace was much more flexible. Because here, there are usually lectures and very specific deadlines, and now we don’t have the backup that you should have.Inf. 2.

Gender and work roles could also be important for the opportunity to telework. Women were sometimes assigned “academic housework” (practical/administrative tasks related to the office environment), which was perceived as a hindrance to telework. Responsibility for staff was described as being associated with high expectations for accessibility and presence at the office, which could limit the possibility of telework. Telework practices in the workgroup could influence the informants’ choice; if a large part of the working group teleworked, the choice was perceived as more legitimate, while if few teleworked the choice could be perceived as inappropriate and avoided.

3.1.2. Telework Challenges and Benefits Academic Work

Telework was viewed as a natural element in autonomous academic work. It provided an opportunity for geographically independent recruitment, thereby facilitating national and international collaborations beneficial for the academic work culture and organization. For example, telework could promote exchange in academia by facilitating internationalization in both research and education. Sometimes telework could complicate collaboration, problem-solving, and performance of work tasks, in which case it was perceived as a threat to the academic social context and work culture. While informants considered telework to be a privilege that should not be taken for granted, they did not support the unlimited practice of telework.

I think that the job wouldn’t be good if everyone worked at home; there would be a different type of culture that wouldn’t be as strong; it would be weaker if everyone sort of just showed up to teach, and then left. There wouldn’t be any sense of community.Inf. 13.

I think that everyone knows or understands that it would be almost impossible to function if everyone were required to be present every day. It would be difficult to recruit staff; it’s already difficult sometimes.Inf. 10.

3.1.3. The Forms of and Conditions for Telework Are Unclear

In general, there was a lack of formal agreement or communication regarding where, when, and how telework could be practiced. Telework was generally practiced independently based on informal agreement with the supervisor and was seen as part of the autonomous academic work. Telework could therefore be perceived as an individual responsibility, which was experienced as freedom as well as associated with demands. The lack of formal guidelines could contribute to irregular and high absences at the office, forcing the workgroup to adapt to those who teleworked. This situation could contribute to stress for those working at the office, as well as those teleworking. Sometimes the workgroup had informal rules for teleworking that competed with the formal guidelines, which contributed to unfair working conditions. Despite this, telework guidelines were generally perceived as negative, coercive, and contradictory to academic freedom. Instead of guidelines, it was suggested that the telework opportunity should be based on reasons given by the academics and adapted to their personal health- and work-related needs.

If someone systematically is working from home full time, nothing happens, it’s just accepted. […] And everyone adapts to those staff; I think that’s wrong, and I think it’s stressful. Those of us who are here must plan our meetings based on that person, instead of that person actively needing to be at work. That’s a problem.Inf. 6.

Then I realized that the first two Christmases, when I was alone at work with the boss, I realized that this actually isn’t right. You have to raise the discussion that it doesn’t seem reasonable that I should be sitting here, that I had to give up traveling to see my family so that I could be on duty on this day between holidays, and no one else is here, since they’re all working from home.Inf. 12.

Managers’ attitudes to and experiences of telework, and trust in the workgroup, could influence the possibility of telework. Some managers viewed telework as a threat to the workgroup’s performance and sense of community and therefore called for a presence at the office. In such situations, the workgroup would need to prove that work tasks and communication could be appropriately handled during telework for telework to be permitted, and managers could refuse to allow telework if they felt that this was not proven. Sometimes telework was only permitted for staff who had a long commuting distance. Managers’ restrictive attitudes toward telework could be perceived as unjustified and outdated and interpreted as a lack of trust in the workgroup. Conversely, managers could be perceived as trusting if they had a positive and permissive attitude toward telework. When managers followed up and evaluated the workgroup’s telework, follow-up in conjunction with staff performance appraisals was perceived as a sign of being considerate, while regular follow-up via telephone conversations was perceived as mistrust and a need for control.

In other words, there’s something old-fashioned, something out of date, about the idea that you get more done if you’re at the office from 8 to 5. Nothing says that more gets done just because you’re physically present with your body. […] So there’s a kind of an “ugly view” of telework that doesn’t have to be true, I think, though sometimes it [telework] can actually be justified.Inf. 13.

I’ve understood this mainly from the department head, that she basically feared that I wouldn’t do my job—not exactly that I’d sit there and twiddle my thumbs, but that I might do things that might benefit myself more than what benefits my work. Since that didn’t happen, she thinks it’s working well and she is positively surprised that it can work well. But it’s possible that if someone else were involved, the outcome could have been different.Inf. 14.

Sometimes the employer provided teleworkers with better broadband, desk equipment, or offered satellite offices, but in general, informants were denied such support as telework was seen as a voluntary choice. One opinion, however, was that academics who had long commutes should always be offered support for the physical work environment related to telework.

3.2. Telework: Balance between Work-Related Demands and Individual Needs at Work

This category describes how telework can both complicate and facilitate teaching and research, provide both practical and social control, and allow work to be adapted to individual needs.

3.2.1. Telework Changes Circumstances for Certain Tasks

During telework, there was generally a clear disposition of tasks. Teaching and meetings were primarily carried out at the office, as this location was perceived as preferable for interaction and collaboration in practical, technical, and social terms. For example, telework could limit accessibility for colleagues and students and make it difficult to collaborate, which was experienced as hampering the quality of work. Research and solitary work were mainly practiced while teleworking, as this option could provide undisturbed working hours and allow concentration. Sometimes the disposition of tasks contributed to a higher burden of teaching and meetings when working at the office. Consequently, some informants felt that all tasks should be carried out at the office.

There are many people [colleagues] who think that you don’t have to be at work at all. I belong to those who believe that you should be at work just because colleagues must talk to each other, both for research and teaching purposes. […] That’s why I think it’s a clear disadvantage if colleagues choose to work from home all the time. The same applies to communication. Email works great, but things don’t come across the same way in email.Inf. 6.

Access to digital technology could enable simple and good communication with colleagues and students regardless of location and contribute to teaching being equally effective when teleworking and working from the office. Sometimes the undisturbed and concentrated working hours associated with telework could provide better conditions for teaching, compared with the office.

[…] Everything is becoming more digital and there is almost no reason to be on campus anymore. Of course I’m speaking just for myself now. I don’t think staff will sit in their offices in the future, because having the lecture recorded is just as effective, so staff may as well sit at home and teach.Inf. 18.

3.2.2. Telework and the Nature of Work Tasks Provide Freedom, Flexibility, and Control

The combination of autonomous work, access to digital technology, and the opportunity of teleworking could make it possible to perform work tasks anywhere, regardless of location. This could give a sense of freedom and work control by providing temporal and spatial flexibility, but it could also make a physical presence at the office seem meaningless. The possibility to switch between various physical environments (such as cafés, libraries, nature, and abroad) could give new impressions, and generate inspiration and creativity that could benefit both writing and research. Another reason for the choice of telework was that it could provide control over work-related social and digital interaction.

So for me it [telework] is very important because I can’t sit at school all the time, it’s impossible; staff are always running around. It’s also great that I can sit anywhere. The university doesn’t require me being present.Inf. 18.

3.2.3. Telework Can Provide Conditions That Promote Concentration and Efficiency at Work

Telework was described as a necessity for social seclusion that could enable uninterrupted and cohesive working hours, thereby facilitating efficiency. When teleworking, colleagues had greater respect for the need for undisturbed working hours, which made it easier to achieve concentration in order to finish the job. Sometimes teleworking from temporary accommodations, or while commuting, was seen as particularly beneficial for concentration and efficiency because it provided privacy from both colleagues and family. If the office environment was unable to provide conditions for undisturbed work, teleworking could be necessary to promote concentration and improve work performance. Conversely, the need for telework could be reduced if the office provided separate and undisturbed workspaces.

I feel like I can work in peace and become enormously effective when I work at home because there are no interruptions or anything. […] I think I’m more focused at home because I’m relaxed, and I have my stuff and I know that I can go down and make a cup of coffee whenever I feel like it. […] So the work environment is really relaxed, which is great for me—especially when I have to concentrate.Inf. 24.

Telework was seen to promote efficiency because working hours and the work environment could be adapted to meet the needs of family and private life. At the same time, the inadequate structure of working hours and breaks when teleworking could result in overtime work and insufficient recovery, which could impair efficiency. Sometimes the separation from leisure and family activities, provided by the office environment, could result in more efficient work.

[…] I’m probably better at working efficiently and taking breaks when I am at work. I go and get coffee and chat with someone and that kind of thing. If I’m at home, who knows, the thoughts are there all the time. I can sit, I can lose myself in work and be like, “How did it get to be lunchtime already!?” But at work, someone comes and asks if you want to go have coffee or lunch or something.Inf. 23.

3.3. Telework Changes the Boundary between Work and Private Life

This category describes how the boundary between work and private life can be changed, challenged, and requires special strategies when teleworking.

3.3.1. Telework Can Change the Balance between Work and Private Life

Telework could facilitate private activities such as picking up and dropping off children, care of elderly parents, and visits to relatives abroad by making it possible to adapt the time and place of work as needed. The possibility to adapt could be perceived as a requirement for successfully coping with family needs, which in turn could be considered essential for working in academia. Telework could also facilitate adaptation and coping with the high and uneven workload associated with teaching by allowing rest and recovery, as well as by making it possible to work during leisure time.

I have two young children, so it’s nice to be able to start a load of laundry, check email and alternate work tasks with other things in life that need to be done. It’s convenient. […] But when I’m at home, I might take an extra break or two in the middle of the day and then work for a while in the evening again.Inf. 21.

When working at home, the lack of a workstation and the inability to physically detach from and leave the workplace could make it difficult to stop thinking about work and relax after working hours. Without any structure for working hours and breaks, telework at home, from temporary accommodations, or when working abroad could be experienced as boundless.

I think it’s related to the fact that when you’re at work, you leave a physical place, you leave a building, you go out. When I’m home, I’m still at work if you view the home as a workplace. And I’m not so structured that I can walk out of my little office and close the door behind me; no, the workplace is still there. […] It’s easier to reach the ending when you’ve done something at the office and get to go home than when you work at home.Inf. 23.

3.3.2. Telework Contributes to Extended Working Hours

The informants generally stated that they worked more than what was required for their position, and this was perceived as natural for ambitious academics. Passion for the job, a sense of duty, quantitative demands, commuting, and business trips could make it difficult to control and limit working hours when teleworking. Telework during leisure time could be viewed as necessary because of a high workload, lack of staff, and deadlines. Digital availability and constant access to work materials in the home could also provoke telework during leisure time.

I don’t pay close attention to my working hours; I have colleagues who precisely count how many hours they work. I’m more flexible, I feel that the job has to be done, regardless. And if I don’t do it, no one else will do it, or I will put a colleague in a bad position […] Before, this was one of the reasons I quit. I hit the wall because back then I worked too much […] But this is a problem staff have in academia. It’s hard to just turn off the button. You go around pondering and thinking about a lot of different things.Inf 6.

With telework, sleeping in and household chores could cause working hours to be shifted to evenings and weekends. At the same time, leisure and family activities when teleworking could result in routines that facilitated limiting working hours. Strategies for working hours and breaks, previous experience, self-discipline, and mental flexibility could be required to succeed in drawing boundaries between work and leisure when teleworking. Some had learned to draw such boundaries after experiencing unlimited telework that culminated in sick leave.

In the past, I worked a lot at home at night, in late evenings and on weekends. There were absolutely no boundaries then. […] If I hadn’t been able to work at home, I wouldn’t have gone as deep into it. Now of course I don’t blame this, but for me it was a big disadvantage, or I see a risk there, that “if I just sit for one more hour,” or “I can leave these things out, I’ll deal with them tonight,” or thoughts like that. Now I don’t work in the evenings at home, so it isn’t a problem now, but it’s definitely a risk when the computer is at home with you anyway. Somehow, it’s just rigged for this type of situation.Inf. 22.

3.4. Formal and Informal Work Relations Can Be Challenged by, and Benefit from, Telework

This category describes how social relationships, interaction, communication, and support at work can be challenged by, and benefit from, telework, and even justify the choice of telework.

3.4.1. Telework Can Entail Both Opportunities and Obstacles for Communication and Support at Work

The physical distance to colleagues and students associated with teleworking could complicate practical and social accessibility both when teleworking and working at the office. For example, teleworking could make it difficult to locate, reach and communicate with colleagues and managers. This might limit collaboration and problem solving, and possibly contribute to less transparency and a weaker sense of community in the workgroup. Absence from the office could also entail less accessibility and communication for students. Teleworkers with long commutes sometimes experienced difficulties in meeting the expectations of colleagues regarding availability and work performance. At the same time, social interaction and communication with colleagues and students could be equally effective, regardless of work location, provided that the workgroup had procedures for communication and accessibility with respect to telework.

But obviously, when you’re often away from the university, as I am, you aren’t directly involved in the daily coffee room discussion; you’re probably a bit of an outsider. And then it depends on how much you need this social interplay and interaction. I don’t think I directly suffer from this, because I have meetings with some colleagues at least once a week. And since we have a lot of contact every week, I can’t say that I directly suffer from this, but it’s the type of thing that I may hear about later when I get to work, that something has been the topic of discussion off the record. Or that something has been agreed and I haven’t been part of the discussion.Inf. 14.

From a practical standpoint, telework could mean poorer access to work materials, equipment, and physical premises, which could sometimes make it difficult to perform certain tasks.

3.4.2. Telework Can Change the Workgroup Dynamic

The informants perceived that there was a risk that teleworking colleagues were forgotten and perceived as invisible. Sometimes dissatisfaction and mistrust were directed at those who were absent from the office because of telework. This could threaten the cohesion of the workgroup and contribute to feelings of exclusion among those who teleworked. Another consequence could be that telework was avoided, or the opposite, that teleworkers avoided the office. In the culture of some academic fields, telework was perceived as a threat to the traditions of physical presence and social interaction, which could lead to negative attitudes and restrictive approaches to telework.

[within the field] there is a very strong tradition of being at work constantly. Then you take coffee breaks, and you go home. Most of all, you arrive at work early and you are always at work, otherwise you aren’t working. […] And there, that culture can be affected if you work from home.Inf. 23.

But when you live less than a kilometer away and only come in every other week and spend just part of the day—that’s a problem. There may be conflicts between colleagues. Someone might say, “since they’re only here a few times a month, I’m not going to come here either,” and it creates conflicts.Inf. 4.

With telework, weak social relationships and inadequate communication within the workgroup could lead to the loss of a sense of identity and work context. This could, in turn, lead to experiences of loneliness and exclusion while teleworking. When colleagues met less frequently because of telework, social interaction could seem unfamiliar and unnatural. At the same time, telework facilitated pauses and variation in the social interactions of the workgroup, which could make the social work relations more appreciated. The physical distance perceived in digital meetings during teleworking could even facilitate conflict management by neutralizing power relationships and emotionally charged atmospheres.

So then I thought that, hmm, it will be interesting to see what this will be like when we sit remotely and have to resolve a conflict. My experience was that it was quite pleasant not to have those two face-to-face, or to have them in the same room, since one of them radiated insults, contempt, etc. In other words, there is often a lot of negative energy floating around. Meanwhile, the other party was extremely factual, objective, correct, and really knew what was going on. […] I think that the balance of power between these staff was blurred to some extent because they sat remotely.Inf. 19. Manager, regarding conflict management.

3.4.3. Work at the Office: Practical, but Not Socially Motivated

While presence at the office could be associated with practical benefits for work performance, it could lack social incentives. For example, working alone could make a presence at the office seem pointless, which sometimes contributed to the choice of telework. Sometimes telework was chosen because informants did not need the social community offered by the workgroup. A strong work culture with a social community was therefore described as important to motivate presence at the office.

Suddenly I’m in a situation where I’m working alone more, and I think that also makes a difference for me. I don’t have the same social incentive [to go to the office]. The work does not automatically make progress just because I’m at my desk […]Inf. 12.

3.5. Telework Can Entail Opportunities and Challenges for Health and Well-Being

This category describes how the flexibility of telework concerning time and space can facilitate and complicate the adaptation of physical and mental recovery at work while enabling and challenging health and well-being at work.

3.5.1. Telework Can Provide Better Conditions for Health and Well-Being

Telework could be viewed as freedom and a valuable benefit that brings job satisfaction and a sense of well-being. Some informants even described telework as essential for job satisfaction and health at work, and as a reason for keeping the job. Telework was also described as essential for mental recovery by facilitating an undisturbed, calm, and relaxed work environment. For example, telework could provide the privacy that facilitated recovery from stress and fatigue caused by the social impressions and interactions at the office. Some informants described how telework could facilitate a gradual return to work following burnout-related sick leave. The option to telework could be viewed as a sign that employers/managers trust the individual and the workgroup, which contributed to a calm and secure feeling at work. The feeling of trust could also strengthen job satisfaction, loyalty, and work motivation.

[…] knowing that my employer has confidence in me, that they trust that I handle my job in the best way. Trust is also incredibly important. […] I also feel that I must remain committed and on task, because they believe that I am committed and on task. So it’s absolutely important for job satisfaction.Inf. 20.

[…] Having the knowledge or awareness that it’s okay to work from home […] makes it easier to deal with mental stress. […] So just the knowledge that this flexible form of work is a possibility, that it is permitted, I think makes it a very stress-free workplace.Inf. 3.

Reduced commuting when teleworking could also allow breaks to promote physical recovery, such as exercise and spending time outdoors in nature. The opportunity for variation, changing rooms, and even geographic location when teleworking, could contribute to the experience of work as more exciting, fun, and meaningful. Work-related physical recovery could also be facilitated. For example, telework could make it possible to adapt the workday to the need for physical variation and exercise, which was perceived to benefit coping with pain and physical discomfort.

I have some mobility problems, so I don’t feel as physically exhausted after spending the day teleworking. And since I don’t have to wake up as early, I start at 8:00, I also get more rest.Inf. 16.

The choice of telework could be a strategy to escape an unpleasant work environment at the office, and thereby contribute to well-being and job satisfaction. Demands for accessibility, a shortage of workspaces, shared/open/transparent and/or noisy premises with poor lighting were described as unpleasant aspects of the office that contributed to the choice of telework.

I usually sit at home and do that because at school I’m disturbed by the students running around all the time and our office has glass walls and doors so you can’t hide in the office. They come and knock on the door, and you have to answer. We have an “open door policy” when we’re there. So I’m rather easily disturbed when I’m there.Inf. 18.

I share an office with a colleague, our office faces a courtyard, so we have no natural daylight and it’s quite dark in our office. I think I need to have this occasional boost of light. So sometimes I leave work and go home, after lunch for example, just to get some light.Inf. 17.

3.5.2. Telework Can Provide Worse Conditions for Health and Well-Being

Digital accessibility and the inability to physically leave work after the end of the workday could mean worse conditions for recovery when teleworking. For some, telework meant unlimited availability and working hours that culminated in sick leave for burnout. The home could be experienced as a workplace when teleworking, which made it more difficult to relax and rest after working hours. Adapting work to leisure and family activities and commuting when teleworking could lead to irregular work hours, and contribute to a bad conscience, overtime work, stress, and sleep problems.

[When teleworking] your circadian rhythm may not be the best and you might experience fatigue, say if you work at night instead of during the day because you do things with the family in the daytime or the afternoon.Inf. 2.

You can probably see me as an example of “this is what can happen when you’re constantly available” and especially when you think about the job constantly. Of course, I don’t want to blame everything on telework, but the option of being available everywhere is important for your view of work and working hours.Inf. 23.

With telework, the workgroup’s social and interactive tasks could be postponed and concentrated on office days, causing a heavy and stressful workload at the office. This situation could cause dissatisfaction, conflicts, and stress in the workgroup. The lack of social interaction and communication with colleagues when teleworking could contribute to feelings of isolation and less job satisfaction. The work performance may seem less satisfying when teleworking compared with working at the office because colleagues cannot see or acknowledge the efforts. The physical absence of colleagues when teleworking made it easier to skip breaks or spend them in front of the computer. The lack of routine for working hours and breaks, as well as a poor ergonomic work environment with prolonged sitting, could result in physical problems when teleworking. Telework could also give less opportunity for exercise and less access to joint physical activities.

[…] we’ve said that it’s okay to work from home a maximum of two times a week. And that is mainly for social reasons. I’m responsible for this policy choice, because after a while I was alone here since so many staff were teleworking. […] And that means that every case that comes in ends up on my desk, no matter what. My workload became ridiculously large.Inf. 6.

If you stay at home, then you end up sitting more on your chair when you work. So it isn’t as healthy physically. If you spend too much time working at home, I think you’d be socially isolated, so many things are solved in the corridor too.Inf. 13.

3.6. Teleworking When Ill: A Culturally Accepted Opportunity and Risk

This category describes telework as a natural alternative to sick leave and leave to care for a sick child, which may offer practical benefits, but may also be negative for health.

3.6.1. Teleworking When Ill Is an Opportunity and a Risk

Telework was generally perceived as a possible and acceptable alternative to sick leave or leave to care for a sick child; most informants stated that they had never been on sick leave while working in their current position, regardless of illness. Teleworking when ill/caring for a sick child allowed the freedom to adapt the job to the individual state of health and could prevent the spread of infection at the office. Sick leave was usually associated with negative consequences at work, so by teleworking when ill, such consequences could be avoided. For example, when on sick leave, work would be postponed, which would increase the workload both personally and for colleagues. This could contribute to stress that made it difficult to rest while on leave, which made sick leave seem pointless. At the same time, informants described teleworking when ill or caring for a sick child as fundamentally wrong, risky for their health, and even viewed as bad for the children.

Of course it’s nice to work if you’re able to do so, if you aren’t so ill that you need to take sick leave. But then at the same time, I think in principle that if you’re ill, you shouldn’t work. But if you have a teaching job like I have, it means that there will be huge amounts of work when I come back and that makes me prefer to work. […] I do it for my own sake, so that I don’t have to deal with twice as much work when I return.Inf. 21.

3.6.2. Teleworking When Ill Is Culturally Accepted

Academic freedom, flexibility, and access to digital technology could contribute to telework being viewed as, and becoming, a natural alternative to sick leave/leave to care for a sick child. Sometimes teleworking when ill/caring for a sick child was by agreement with the manager or workgroup; in some cases, it was a consequence of sick leave being perceived as not allowed.

I was lying in bed, wondering “should I call in sick now?” So I spoke with my manager and asked whether there was anything that I absolutely had to do. There really wasn’t anything, so I could really just leave it alone and not call in sick. And then the next day I could just lie in bed and work and there was nothing unusual there. And that’s something that I would think is positive, to be “sickness present” and avoid this anxiety about the unpaid first day of sick leave.Inf. 24.

3.7. The Economy and the Environment: An Aspect of Teleworking

This category describes how telework is motivated by economic and environmental aspects for both society and the individual.

The Economy and the Environment Influence the Choice of Telework

Telework could reduce private costs for work-related commuting, which sometimes motivated the choice of telework. However, telework could also increase private expenses such as business travel, temporary accommodation, and subsistence, especially for those living far from the workplace. The choice of telework could be a way to reduce commuter traffic with respect to the environment and traffic safety.

If I had had to commute by car, it would not have worked, because I would not have been able to work in the car, it’s more dangerous in the car, you can crash the car, road conditions can be bad, and it’s extremely bad for the environment. […] So long-distance commuting works best if you live in the more densely populated parts of Sweden and where there is a proper railway.Inf. 7.

[…] All that traveling around and everything, it costs a lot of money and it has an impact on the environment. Some staff fly and some travel by train, but why should we do so, when we have such good tools?Inf. 18.

4. Discussion

We aimed to investigate academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework within the academic context. Our findings showed seven qualitatively different ways in which academics experienced and perceived telework in academia. In the following section, we will discuss the most prominent findings within the outcome space of societal, organizational, workgroup, and individual aspects (Figure 1), which were related to work tasks, coping strategies, workgroup relations, and policies/regulations.

4.1. The Importance of Work Tasks

The academics’ self-regulated and flexible work practice (referred to as “the academic freedom”) was described as facilitating the choice of telework, which is in line with previous findings showing that autonomous and flexible work characteristics may facilitate telework [1,4,5]. At the same time, the present findings show that several aspects of the organization and work culture may have an impact on the possibility of academicsto telework [4,5,29]. Firstly, we found that teaching was sometimes perceived as preventing telework because of its interactive and collaborative character, while research was generally associated with more freedom and flexibility and thus, with better conditions for telework. These descriptions may be questioned as both teaching and research tasks could be considered highly collaborative, but this is similar to studies showing that academics perceive that teaching reduces their professional freedom and sense of identity, while research rather seems to affirm such professional values [15,19]. Secondly, we found that women in academia sometimes could be assigned “academic housework” (e.g., administrative work tasks) that require office presence, which may prevent them from teleworking. The problem of “academic housework” has previously been recognized in academic institutions and has been associated with e.g., decreased research performance and reduced well-being among women [20]. Moreover, in some studies, even teaching has been defined as a part of the “academic housework” [18,20]. Thirdly, our findings show that academics with managerial responsibilities may have less possibility to telework, because of higher expectations on them being available at the office premises. This is in contrast to reports showing better conditions for telework among managerial positions [1]. Hence, instead of assuming that academics’ autonomous and flexible work characteristics per se will facilitate the choice of telework, more attention should be directed towards work tasks and professional culture as these aspects seem to impact staffs’ possibility to telework.

The informants’ disposition of work tasks during teleworking, where collaborative tasks (e.g., teaching, meetings) were mostly concentrated on office days, and solitary tasks (e.g., research) were generally performed while teleworking, was described as causing an unfair and stressful workload in the workgroup, which could impair the quality of work performance. Similar issues have been recognized among other occupations where telework has been seen to create feelings of injustice, reduce work satisfaction and hamper work performance in collaborative and less autonomous work tasks that are dependent on co-worker presence [30]. In contrast, our findings also show that the academics with extensive ICT experience and those involved in online teaching did not perceive these challenges, instead, they considered all work tasks to be satisfactorily performed while teleworking. Additionally, we found that office presence was sometimes perceived as meaningless and unfavorable for work performance when performing tasks that required deep concentration (e.g., research) because the office environment implied recurring social interruptions. It has previously been claimed that academic work requires an environment that “foster deep concentration and focus, usually for an extended period” [31] and that insufficient working conditions may hamper academics’ teaching and research performance [18,20]. Findings from other branches show that staff may question the meaning of office presence when the office environment is perceived to cause unnecessary disruptions that may hamper rather than improve work performance [32,33]. Thus, our findings are in line with studies showing that decreased office presence and restricted face-to-face interactions with co-workers may be beneficial for work performance [32]. In summary, the findings suggest that a lack of congruence between office premises, work tasks, and professional needs may force the choice of telework and reduce staffs’ willingness to work at the office.

4.2. Telework as a Coping Strategy

In general, studies on telework among knowledge and information workers show that work-to-family adaption is the strongest motive for teleworking [4,5]. However, it has been suggested that expansion of work hours is an even stronger motive [34]. In our findings, the choice of telework was primarily motivated by family-to-work adaption, i.e., work-related demands were recognized as the strongest reason for teleworking. For example, telework enabled the expansion of work hours, thereby providing a valuable resource for coping with high work demands. Additionally, because of the high workload and lack of resources (e.g., personnel), telework became a natural and necessary choice to maintain work performance and cope with work-related stress. In the long run, this choice may be counterproductive as previous studies show that sickness-presenteeism and insufficient work-related resources may reduce academics’ work performance and lead to stress [18,20]. Considering this, the choice of telework may be forced by, and mask, an unhealthy work situation that could hamper academics’ work performance and impair their health. This should be considered when evaluating telework options in academic institutions.

In agreement with previous research among academics [13,14], as well as among other occupational groups [4,5,19,35,36,37], we found that telework could lead to boundless work because of insufficient structures for work time and breaks, unlimited access to working materials, extended working hours and high work demands. As seen in studies on boundary theories, the transition between private and professional roles, forced by work-nonwork integration, entails substantial psychological effort that might cause mental strain and impair mental recovery after teleworking [11]. In addition, we found that strong work commitment and passion for the job could challenge the informants’ ability to mentally detach and recover after teleworking, which is similar to findings from other academic work settings [19,38]. According to boundary theories, organizational factors (e.g., work obligations) could prevent individuals from separating their professional roles from their private roles. Hence, the insufficient physical and mental boundaries recognized in the present findings may explain the informants’ difficulties in restricting their working hours when teleworking [11].

However, in parallel to telework being perceived as boundless, it was considered important for mental recovery by providing an escape from the social interaction at the office. In contrast to previous findings showing that ICTs may expand the availability in work [10], our findings show that communication through ICTs could facilitate control over social availability during teleworking. Besides this, telework was also seen to facilitate coping with physical injuries and pain by enabling the adaption of physical activity and rest to individual health-related needs. Sometimes telework was described as facilitating recovery and return to work after long-term sick leave. As we only found one previous study where telework options were implemented as a return-to-work strategy [39], this may be a subject for further investigation in future studies.

4.3. Workgroup Relations

We found that extensive and/or irregular teleworking could hamper workgroup relations by reducing the communication and insight into work processes, challenging the ability to meet co-workers’ expectations, and contributing to e.g., conflicts and social isolation. Similar challenges for workgroup relations have been found previously in academic institutions [38], and other branches [40], and have been seen to change the views of, and attitudes towards, co-workers and create hostile work environments. It has also been found that a high teleworking frequency and insufficient face-to-face interaction between co-workers may lead to dissatisfaction and increase office-based workers’ turnover intention [30,41]. Further, such effects could reduce work motivation and challenge the establishment of a working culture during teleworking [17,30,35,38,42]. As seen in our findings, the work culture within certain disciplines (e.g., pedagogical and health care) could contain negative attitudes towards telework, which could create friction between those working at the office and those teleworking. Along with the negative experiences of telework for workgroup relations, we found that telework could facilitate social seclusion, the alternation between telework and office work, and regular interaction via ICTs during telework, could be beneficial for maintaining good work relations. This has also been recognized previously among other professions i.e., the alternation between office work and telework, and regular fact-to-face interaction, attenuate the negative impact of telework on workgroup relations [32]. According to the socio-technical system approach, problems with social exclusion among teleworkers may be prevented by teleworkers receiving proper organizational and technological support [12]. Assuming that, academics with a high level of technological skills, such as those with online teaching experience, are more satisfied with the support, they may perceive fewer barriers to social interaction when teleworking compared to academics who mainly teach on campus. This may explain some of the diversity in experiences found in this study.

4.4. Future Challenges for Telework Options in Academia

The academics in the present sample described co-worker relations to be most important for work satisfaction and work performance during telework, which is similar to previous findings from studies on other academic work settings [17,18,43]. Among other professions, managerial support is generally claimed to be the most important resource for teleworkers’ well-being and work performance [4,5,41,43]. The difference between such findings and those found in the present study may be explained by the fragmented managerial roles within academic institutions, which implies a high degree of individual responsibility and self-regulation [15,20,42]. Our findings may suggest that the professional culture could influence the work-related needs during telework. Therefore, to promote sustainable working conditions for telework in academic institutions, future studies should investigate the importance of co-worker relations for well-being and work performance among frequent teleworkers as well as non-frequent teleworkers. It could also explore the role of leadership for academic telework options.

Formal telework policies have repeatedly been proposed as a strategy for employers to regulate telework options and for securing good working conditions during telework [44], especially because of the COVID-19 pandemic [45,46]. The present findings suggest that it might be difficult to formalize telework options in self-regulated and flexible work settings, among experienced teleworkers. For example, we found that the possibility of academics to telework was highly dependent on their closest manager’s attitude rather than on the employer’s formal decision on telework. Further, workgroups sometimes adopted informal and implicit rules for telework that could hinder the acceptance and practical function of formal policies. In general, formal policies for telework were unknown or perceived as unclear, instead, telework was self-regulated, which was mostly seen as a positive effect of the “academic freedom”.

Even though the lack of formal policies seemed to contribute to several work-related problems such as an irregular presence at the office and an uneven distribution of work tasks, the informants were hesitant about telework policies as these were perceived as a threat to the “academic freedom”. It has previously been argued that telework options decrease employers’ regulation and increase staffs’ self-regulation [47,48]. Considering the combination of academics’ self-regulated work practice and the low managerial regulation in academic institutions [15,18,49], telework options may contribute to a synergy effect where academics are more or less decoupled from the organizational regulation. Therefore, it may not come as a surprise that such highly autonomous professions oppose initiatives that may change their level of self-regulation. Further, it may also be seen as a natural reaction that regulatory telework initiatives among these professions are interpreted as managers’ lack of trust and need for control. Such interpretations might even be justified as previous research shows that managers may experience a loss of control during telework and therefore may become mistrusting and reluctant toward telework options [5,50]. It has also been seen that academics may perceive less autonomy and work influence when managers regulate their telework [7,38,51]. Accordingly, before implementing and regulating telework options, it is important to consider the professional culture and managers’ attitudes toward telework options as this may determine the success of such initiatives.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

In the present study, we used a qualitative study design with a phenomenographical study approach to gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of telework. Because the use of theories may limit research findings by narrowing them down to pre-defined categories, we adopted an inductive study design to facilitate a broad and unconditional investigation of the academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework [52]. Additionally, to maintain this broad approach we did not rely on a specific definition of telework, instead, we included experienced teleworkers who regularly teleworked to some extent. Therefore, this study represents a variation of telework behaviors performed from several different locations, that were alternated with work at the office to a varying extent. This variation may capture the “typical” academic teleworker and may contribute to the understanding of teleworking behaviors in Swedish academic institutions.

Our sample represented academics from various educational and scientific disciplines, from universities of different sizes and parts of Sweden. However, the majority of the informants were women and employed as junior lecturers or senior lecturers and therefore, the findings may not be representative of the population as a whole. For example, the different time spent in teaching and research in academic professions, where junior lecturers or senior lecturers generally are involved in more teaching than professors, may have affected the experiences of telework seen in the present study. In addition, because it is seen that women generally carry a heavier load of “academic housework” compared to their male colleagues, this may also have affected the experiences [18,20]. Further, this study was conducted in Sweden where academic institutions, in general, are known for their liberal organizational management allowing a high level of autonomy and flexibility [18,53]. Hence, our findings may not be transferable to academic institutions in other countries [54,55].

As the authors belong to the academic profession themselves, and have telework experience, this may have affected how the research findings were interpreted. The interpretation of data in the analysis and formulation of the results were, however, discussed in several steps by all authors to take alternative interpretations into account.

The interviews in the present study were performed online using digital meeting rooms. This might have impacted the interview quality because digital meetings may not allow the same interpretation of e.g., body language and facial expressions that are normally possible during physical face-to-face interaction [56]. However, the interview quality was tested in pilot interviews prior to the data collection with no remarks about them, and all informants were experienced users of digital meeting tools. Our experience was that the digital format provided a neutral and relaxed interview setting that allowed the informants to control their own physical and personal space.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated academics’ experiences and perceptions of telework in academic institutions. The findings showed that telework was perceived as a natural part of academic freedom and provided a necessary resource for coping with, and recovering from, high work demands in teaching and research. Telework was mostly self-regulated but the possibility of academics to telework could be determined by work tasks, professional culture, and management. Telework could facilitate the individual’s work but could contribute to challenges for the workgroup. In general, the academics perceived formal regulations of telework as a threat to academic freedom and the possibility of coping with high work demands. Our findings provide knowledge on the working conditions during telework, which may be important for promoting sustainable working conditions for well-being and work performance when academic institutions offer telework options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W., M.H., E.B. and B.W.; investigation, L.W.; formal analysis, L.W. and B.W.; project administration, L.W., M.H., E.B. and B.W.; writing-original draft, L.W.; writing-review and editing, L.W., M.H., E.B. and B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, the University of Gävle funded this project and had no influence on the design, process, or conduct of this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden has approved the study (Reg. no. 2018/399).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all informants involved in this study before the data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data are available by reasonable request (L.W. email: linda.widar@hig.se).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the informants for their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eurofound and the International Labour Office. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg; The International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The European Commission’s Science and Knowledge Service, Joint Research Centre. Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: Where We Were, Where We Head to; Science for Policy Briefs; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Teleworking in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Trends and Prospects; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanoeije, J.; Verbruggen, M. Between-person and within-person effects of telework: A quasi-field experiment. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: How do we optimise health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Vione, K.C. Psychological impacts of the new ways of working (NWW): A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Eddleston, K.A. Is there a price telecommuters pay? Examining the relationship between telecommuting and objective career success. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellner, C.; Peters, P.; Dragt, M.J.; Toivanen, S. Predicting Work-Life Conflict: Types and Levels of Enacted and Preferred Work-Nonwork Boundary (In) Congruence and Perceived Boundary Control. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 772537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.A.; Teo, S.T.T.; McLeod, L.; Tan, F.; Bosua, R.; Gloet, M. The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J.; Eveline, J. E-technology and work/life balance for academics with young children. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustin, D.H. Telecommuting academics within an open distance education environment of South Africa: More content, productive, and healthy? Int. Rev. Res. Open. Distance Learn. 2014, 15, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warren, S. Struggling for visibility in higher education: Caught between neoliberalism ‘out there’ and ‘in here’–an autoethnographic account. J. Educ. Policy 2017, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arántzazu García-González, M.; Torrano, F.; García-González, G. Analysis of stress factors for female professors at online universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, V. The Isolation of Online Adjunct Faculty and its Impact on their Performance. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2011, 12, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, I.; Bjorklund, C.; Hagberg, J.; Aboagye, E.; Bodin, L. Studies in Higher Education An overlooked key to excellence in research: A longitudinal cohort study on the association between the psycho-social work environment and research performance. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 46, 2610–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opstrup, N.; Pihl-Thingvad, S. Stressing academia? Stress-as-offence-to-self at Danish universities. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2016, 38, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohela-Karlsson, M.; Nybergh, L.; Jensen, I. Perceived health and work-environment related problems and associated subjective production loss in an academic population. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Widar, L.; Wiitavaara, B.; Boman, E.; Heiden, M. Psychophysiological reactivity, postures and movements among academic staff: A comparison between teleworking days and office days. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, M.; Widar, L.; Wiitavaara, B.; Boman, E. Telework in academia: Associations with health and well-being among staff. High. Educ. 2020, 81, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2020: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Marton, F.; Pong, W.Y. On the unit of description in phenomenography On the unit of description in phenomenography. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2007, 24, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cibangu, S.K.; Hepworth, M. The uses of phenomenology and phenomenography: A critical review. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2016, 38, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, B.; Dahlgren, L.O. Applying phenomenography in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Morse Saturation Editorial.pdf. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C. “It needs to be the right blend”: A qualitative exploration of remote e-workers’ experience and well-being at work. Empl. Relat. 2021, 44, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T. Co-workers who telework and the impact on those in the office: Understanding the implications of virtual work for co-worker satisfaction and turnover intentions. Hum. Relat. 2007, 60, 1641–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, D.L.; Sullivan, B.O.; Malatzky, C. What COVID-19 could mean for the future of “work from home”: The provocations of three women in the academy. Fem. Front. 2021, 28, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Roloff, M.E. Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D.; Campbell, J. Telework paradoxes and practices: The importance of the nature of work. New Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, M.C.; Glass, J.L. The hard truth about telecommuting. Mon. Lab. Rev. 2012, 135, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Saltmarsh, S.; Randell-Moon, H. Managing the risky humanity of academic workers: Risk and reciprocity in university work-life balance policies. Policy Futures Educ. 2015, 13, 662–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Johansson, G.; Kylin, C. Residence in the social ecology of stress and restoration. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellner, C.; Aronsson, G.; Kecklund, G. Segmentation and integration—Boundary strategies among men and women in knowledge intense work. In Work and Health; Albin, M., Dellve, L., Svendsen, K., Törner, M., Persson, R., Toomingas, A., Eds.; Göteborgs Universitet: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomitro, K.; Kenny, N.; Sheffield, S.L.M. A call to action: Exploring and responding to educational developers’ workplace burnout and well-being in higher education. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2020, 25, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricout, J.C. Using telework to enhance return to work outcomes for individuals with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation 2004, 19, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, T.D. The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F. The impact of extent of telecommuting on job satisfaction: Resolving inconsistent findings. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanuka, H.; Jugdev, K.; Heller, R.; West, D. The rise of the teleworker: False promises and responsive solutions. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F. The impact of superior—subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröll, C.; Nüesch, S. The effects of flexible work practices on employee attitudes: Evidence from a large-scale panel study in Germany. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 1505–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawaguchi, D.; Motegi, H. Who can work from home? The roles of job tasks and HRM practices. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2021, 62, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz de Miguel, P.; Carpile, M.; Arasanz, J. Regulating Telework in a Post-COVID-19 Europe; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Allvin, M.; Aronsson, G. The future of work environment reforms: Does the concept of work environment apply within the new economy? Int. J. Health Serv. 2003, 33, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allvin, M.; Mellner, C.; Movitz, F.; Aronsson, G. The diffusion of flexibility: Estimating the incidence of low-regulated working conditions. Nord. J. Work Life Stud. 2013, 3, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, A.Y.; Frederick, C.M. Leadership in higher education: Opportunities and challenges for psychologist-managers. Psychol. J. 2018, 21, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, L.; Edwards, P. The possibilities and limits of telework in a bureaucratic environment: Lessons from the public sector. New Technol. Work Employ. 2007, 22, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Tijdens, K.G.; Wetzels, C. Employees’ opportunities, preferences, and practices in telecommuting adoption. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F. Approach to Investigating Different Understandings of Reality Phenomenography. J. Thought 1986, 21, 28–49. [Google Scholar]

- López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who is teleworking and where from? Exploring the main determinants of telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J. A study on university teachers’ job stress-from the aspect of job involvement. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2018, 21, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Caudle, D. Walking the tightrope between work and non-work life: Strategies employed by British and Chinese academics and their implications. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailenson, J.N. Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technol. Mind Behav. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).