Does Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from Emerging Economy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. CSR Fulfillment and Risk-Taking from an Agency Perspective

2.2. CSR and Risk-Taking from Stakeholder and Agency Perspectives

3. Data Source, Variable Definition, and Model Setting

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Explained Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variable

3.3. Model Setting

4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation

5. Model Regression Analysis

5.1. Analyses of Model 1’s Regression Results

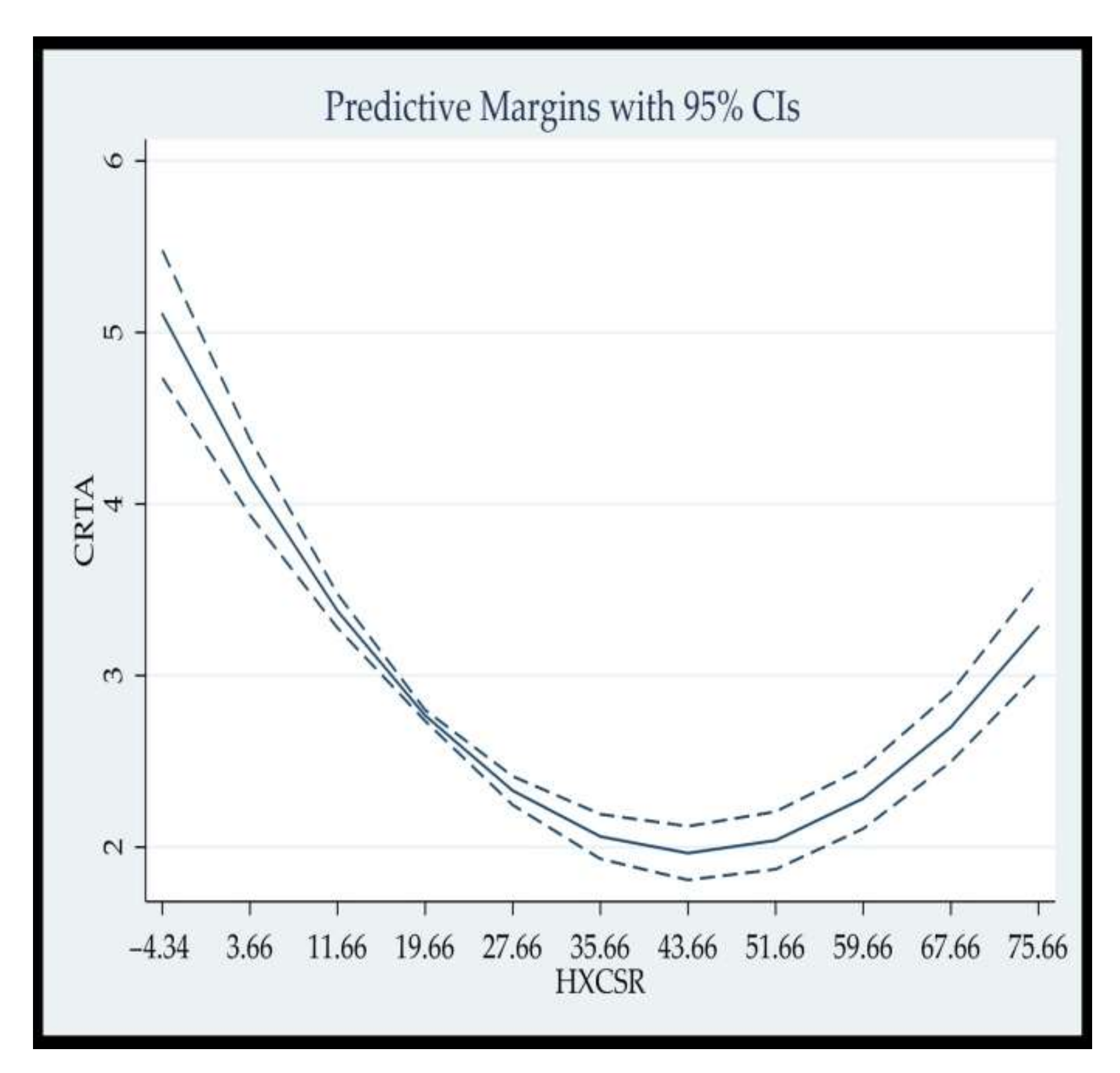

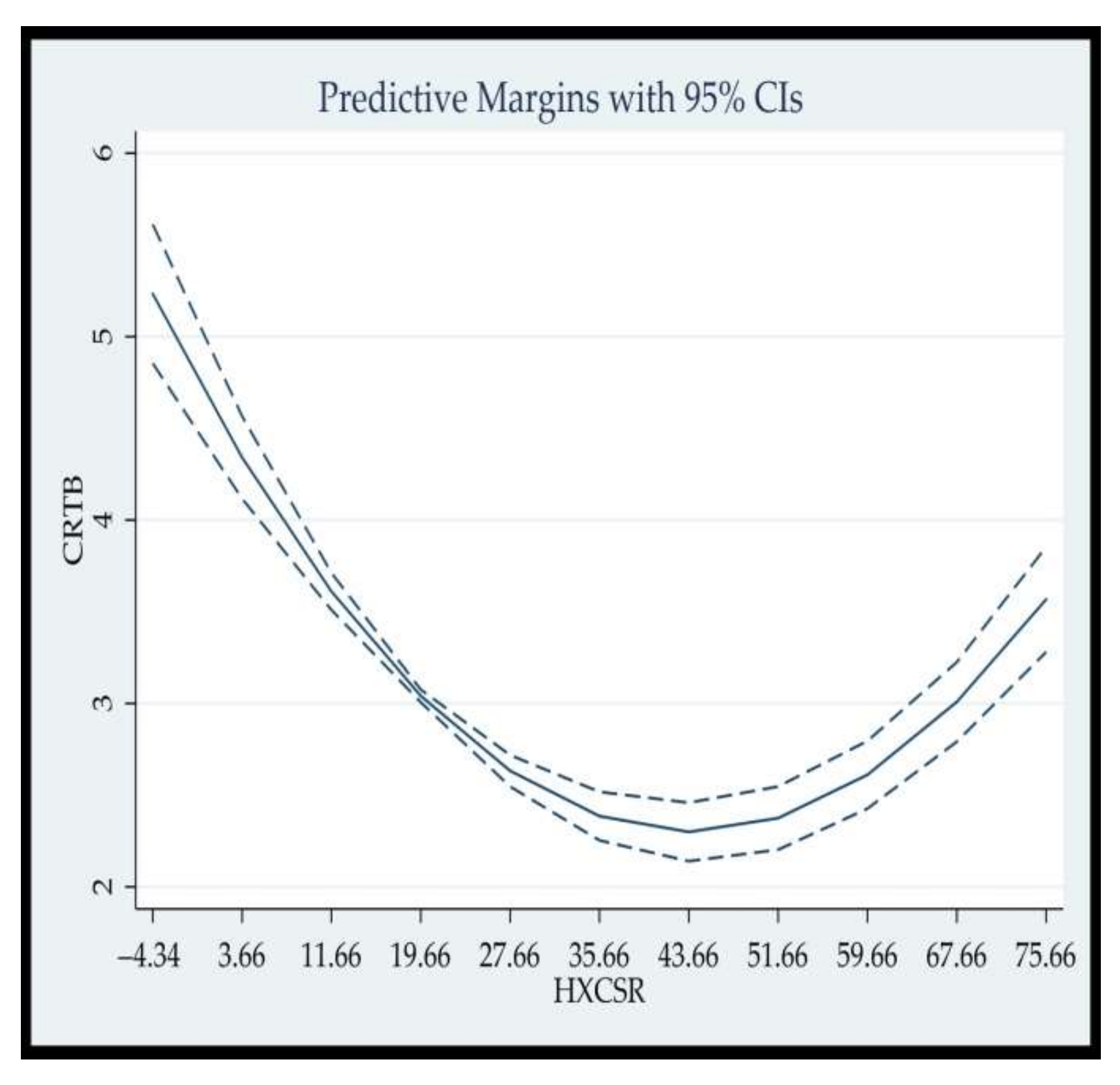

5.2. Analyses of Model 2’s Regression Results

6. Robustness Test

6.1. Two Stage Least Square (2SLS) Method

6.2. Generalized Method of Moment (GMM)

7. Robustness Test

7.1. Analyses Based on the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Sample

7.2. Re-Estimating Explained Variables

7.2.1. Measuring Risk-Taking in Range Form

7.2.2. Measuring CRT with the Volatility of Stock Returns

8. Further Analysis

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

9.1. Conclusions

9.2. Managerial and Theoretical Implications

9.3. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, F.Y.; Yang, M.Z. Can Economic Policy Uncertainty Influence Corporate Investment? The Empirical Research by Using China Economic Policy Uncertainty Index. J. Financ. Res. 2015, 38, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B.B.; Ge, B.S. Inverted U-Shape between Risk-taking and the Performance of New Venture and the Mediating Role of Opportunity Capability. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2014, 17, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. Corporate Governance and Risk-Taking: Evidence from Japanese Firms. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2011, 19, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Marchica, M.T.; Mura, R. CEO Gender, Corporate Risk-Taking, and the Efficiency of Capital Allocation. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 39, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.X.; Liu, M.; Yang, L. Intimacy of Guanxi and the Level of Risk-Taking in Private Enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2020, 41, 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, D.; Cutillas-Gomariz, M.F.; Sanchez-Ballesta, J.P.; Yague, J. Real Earnings Management and Information Asymmetry in the Equity Market. Eur. Account. Rev. 2018, 27, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, L.Y.; Xiao, X.; Cheng, X.K. Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Risk: Based on the Economic Conditions. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.Z.; Jin, Y.P.; He, Z.F. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Performance and Risk: Evidence from Chinese A-share Listed Companies. J. Technol. Econ. 2020, 39, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L.; Li, Y.T.; Wu, X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Risk-Taking Behavior: Based on Resource Dependence Theory. Forecasting 2019, 38, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J. The Impact of Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure on Firm’s Risk-Taking. Rev. Investig. Stud. 2021, 40, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Fraedrich, J.; Ferrell, L. Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases; Nelson Education: Scarborough, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.M.; Masud, M.A.K.; Rashid, M.H.; Kim, J.D. Determinants of Climate Financing and the Moderating Effect of Politics: Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhou, Y.H. Regulatory Uncertainty and Corporate Responses to Environmental Protection in China. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Investment Recommendations: Analysts’ Perceptions and Shifting Institutional Logics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aray, Y.; Dikova, D.; Garanina, T.; Veselova, A. The Hunt for International Legitimacy: Examining the Relationship between Internationalization, State Ownership, Location and CSR Reporting of Russian Firms. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z. Gender Diversity of Board of Directors, Corporate Social Responsibility and Risk-Taking. J. Grad. Sch. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2019, 40, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.J.; Xiao, X.; Jiang, Y.X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Investment: A Study based on Corporate Life Cycle. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 21, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Qasem, A.; Aripin, N.; Ariffin, M.S.M. Corporate Responsibility Disclosure, Information Environment and Analysts’ Recommendations: Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, I.; Ireland, R.D.; Stahl, G.K. Contextualizing Management Research: An Open Systems Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C.; Yin, J.; Soundararajan, V. CSR Logics in Developing Countries: Translation, Adaptation and Stalled Development. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jung, J.-y. Changes in the Influence of Social Responsibility Activities on Corporate Value over 10 Years in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.H.; Ye, Y.; Cheung, W. Separating Control from Cash-flow Rights and the Long-term Returns of Public Listed Firms: Tunneling or Delegating. J. World Econ. 2016, 39, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, X.F.; Wu, S.N.; Yin, H.Y. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Price Crash Risk: Self-interest Tool or Value Strategy? Econ. Res. J. 2015, 50, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.Y.; Zheng, M.; Cao, C.C.; Chen, X.H.; Ren, S.G.; Huang, M. The Impact of Legitimacy Pressure and Corporate Profitability on Green Innovation: Evidence from China Top 100. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, L.H.; Wang, K.D. The “Cover-up Effect” of Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and the Crash Risk of Listed Companies: A DID-PSM Analysis of China’s Stock Market. Manag. World 2017, 33, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.; Hasan, M.M. Firm Life Cycle, Corporate Risk-Taking and Investor Sentiment. Account. Financ. 2017, 57, 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Litov, L.; Yeung, B. Corporate Governance and Risk-Taking. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1679–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, A. Managerial Risk-Taking Behavior and Equity-based Compensation. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 92, 470–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tong, L.J.; Xu, H.R. The Social Network and Corporate Risk-Taking: Based on the Empirical Evidence of Listed Companies in China. Manag. World 2015, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Saveanu, T.; Badulescu, D.; Saveanu, S.; Abrudan, M.-M.; Badulescu, A. The Role of Owner-Managers in Shaping CSR Activity of Romanian SMEs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Conflict between Shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Na, H. Does CSR Reduce Firm Risk? Evidence from Controversial Industry Sectors. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, W.; Li, J.; Shen, H. Corporate Social Responsibility Development and Climate Change: Regional Evidence of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Ji, L. Litigation Risk and Corporate Charitable Giving: An Explanation from the Perspective of Reputation Insurance. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2017, 20, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.S.; Yang, S.L. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance under the Chinese Context: Based on the Contrastive Analysis of Large, Small and Medium-size Listed Companies. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2016, 24, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Rivers, C. Antecedents of CSR Practices in MNCs’ Subsidiaries: A Stakeholder and Institutional Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanina, T.; Aray, Y. Enhancing CSR Disclosure through Foreign Ownership, Foreign Board Members, and Cross-listing: Does It work in Russian Context? Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021, 46, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Cui, J.; Jo, H. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Firm Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 563–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.B.; Cui, K.X. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility to Firm Default Risk. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How Does Corporate Social Responsibility Contribute to Firm Financial Performance? The Mediating Role of Competitive Advantage, Reputation, and Customer Satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.C. The Relationships between Employees’ Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility, Affective Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Cross-level Analysis of Commitment-based Human Resource Management Practices. Manag. Rev. 2015, 27, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M.; Xu, G.H.; Shen, Y.; Dou, X.C. Research of Dynamic Relationship between Voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure of Private Companies and Financial Constraints. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Du, J.; Zhang, W. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Innovation Sustainability: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Religious Belief and the Keynote of Individual Social Responsibility of Senior Executives: From the Perspective of Individual Donation Behavior of Senior Executives in Chinese Private Enterprises. Manag. World 2016, 32, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Risk Taking and Firm Value. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Performance: Analysis of Triple Bottom Line Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Marchica, M.T.; Mura, R. Large Shareholder Diversification and Corporate Risk-taking. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 3601–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.G.; Yu, M.G. Nature of Ownership, Market Liberalization, and Corporate Risk-Taking. China Ind. Econ. 2012, 26, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Boubakri, N.; Cosset, J.C.; Saffar, W. The Role of State and Foreign Owners in Corporate Risk-Taking: Evidence from Privatization. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 108, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.T.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Li, H.D.; Li, S.Q. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Price Crash Risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, K.J.; Tan, J.S.; Zhao, L.M.; Karim, K. In the Name of Charity: Political Connections and Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility in a Transition Economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 32, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdora-Aksak, E.; Atakan-Duman, S. Gaining Legitimacy through CSR: An Analysis of Turkey’s 30 Largest Corporations. Bus. Ethics 2016, 25, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxfield, S. Reconciling Corporate Citizenship and Competitive Strategy: Insights from Economic Theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Chi, R.Y.; Zhang, W. A Research on the Mechanism for Implementation of Firms’ SCSR Program. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 40, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Sandberg, J. The Problematizing Review: A Counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s Argument for Integrative Reviews. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, M.G.; Li, W.G.; Pan, H.B. Managerial Overconfidence and Corporate Risk-Taking. J. Financ. Res. 2013, 36, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bargeron, L.L.; Lehn, K.M.; Zutter, C.J. Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Risk-Taking. J. Account. Econ. 2010, 49, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.B.; Wen, W.; Wang, D.H.; Shen, W. Managerial Power, Internal and External Monitoring and Corporate Risk-Taking. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2018, 38, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.F.; Liu, J.H.; Zeng, H.X. Impact of Water Information Disclosure on Corporate Risk-Taking Level: Evidence from High Water-Risk Industry. J. Environ. Econ. 2020, 5, 54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.H.; Jin, L. Corporate Governance, Corporate Social Responsibility and Accounting Information Relevance. Mod. Econ. Sc. 2016, 38, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, X.F.; Xu, X.M.; Xu, R. Management Opportunistic Behavior in the Compulsory Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence Base on A Share Listed Companies. J. Manag. Sci. China 2018, 21, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.P.; Liu, Y. External Environment, Internal Resource, and Corporate Social Responsibility. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2014, 17, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hung, M.Y.; Wang, Y.X. The Effect of Mandatory CSR Disclosure on Firm Profitability and Social Externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.; Li, F.; Shi, Y. CEO Risk-Taking Incentives and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N.; Liu, L.; Haizhi, W. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Productivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, X.P.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.H. Stakeholders Pressure, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Firm Value. Chin. J. Manag. 2016, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Haans, R.F.J.; Pieters, C.; He, Z.-L. Thinking about U: Theorizing and Testing U- and Inverted U-Shaped Relationships in Strategy Research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1177–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, V.; Lent, L.V. The Endogeneity Bias in the Relation between Cost-of-Debt Capital and Corporate Disclosure Policy. Eur. Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 677–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, K.; Kryzanowski, L.; M’Zali, B. Social Performance and Firm Risk: Impact of the Financial Crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Guo, J.E.; Su, K. Do Firms with Female CEO Have Lower Corporate Risk-Taking? Based on the Analysis of CEO Gender. Forecasting 2017, 36, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thuy, C.T.M.; Khuong, N.V.; Canh, N.T.; Liem, N.T. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Financial Statement Comparability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, A.; Imbens, G.W. Large Sample Properties of Matching Estimators for Average Treatment Effects. Econometrica 2006, 74, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Sa, C.L.; Masud, M.A.K. Predicting Firms’ Financial Distress: An Empirical Analysis Using the F-Score Model. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yu, W.L.; Yang, M.Z. CEOs with Rich Career Experience, Corporate Risk-Taking and the Value of Enterprises. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 33, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K. Mercantile Culture, Risk Taking and Firm Value. J. Zhejiang Gongshang Univ. 2017, 26, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, I.; Jiang, D.; Kumar, A. Corporate Policies of Republican Managers. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2014, 49, 1279–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belloc, F. Corporate Governance and Innovation: A Survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2012, 26, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, G. Can fund shareholding inhibit insufficient R&D input? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248674. [Google Scholar]

- Su, W.C.; Peng, M.W.; Tan, W.Q.; Cheung, Y.L. The Signaling Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility in Emerging Economies. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, G.P.; Lin, W.F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Credit Spreads-An Empirical Study in Chinese Context. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2016, 17, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Tian, G.G. Mandatory CSR Disclosure, Monitoring and Investment Efficiency: Evidence from China. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 595–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wan, R.; Song, V.Y. Pyramidal Structure, Risk-Taking and Firm Value: Evidence from Chinese Local SOEs. Econ. Transit. 2018, 26, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nature | Symbol | Name | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | CRTA | Corporate risk-taking | The standard deviation of Adj_ROA based on Net income |

| CRTB | The standard deviation of Adj_ROA based on Profit before interest and tax | ||

| Explanatory variable | HXCSR | CSR fulfillment | CSR score published by Hexun.com |

| Control variable | LEV | Asset-liability ratio | Total liabilities/total assets |

| TAT | Total asset turnover | Current operating income/average total assets; the average total assets is the average of total assets at the beginning and end. | |

| GROWTH | Sales growth rate | (Current sales revenue—previous sales revenue)/previous sales revenue | |

| NPM | Net profit margin on sales | Net income/sales revenue | |

| AGE | Company age | The periods from the establishment of the company to the end of the observed year | |

| ShrZ | Ownership concentration | The shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder/that of the second largest shareholder | |

| BDS | Board structure | The proportion of independent directors on the board of directors | |

| AUDIT | Audit opinion | Dummy variable, 1 for the standard unreserved opinion; otherwise, 0. | |

| LnASSET | Enterprise scale | The natural logarithm of total assets at the beginning of the period | |

| LnSALARY | Executive compensation | The natural logarithm of the top three executive compensations | |

| STATE | Property attribute | Dummy variable, 1 for state-owned enterprises; otherwise, 0. | |

| BETA | Systematic risk | Based on Capital Asset Pricing Model, Beta coefficient is estimated from the data in the latest 2 years. | |

| YEAR | Year | Annual effect | |

| IND | Industry | Industry effect, based on the “Guidelines on Industry Classification of Listed Companies”, a total of 16 industry dummy variables are set accordance to categories. | |

| ε | Composite error term |

| Variable | Mean | Median | Maximum | Minimum | Deviation | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRTA | 2.849 | 1.512 | 22.349 | 0.070 | 3.665 | 9957 |

| CRTB | 3.124 | 1.733 | 23.681 | 0.089 | 3.896 | 9957 |

| HXCSR | 25.561 | 22.350 | 76.020 | −4.340 | 17.650 | 11,371 |

| LEV | 49.006 | 49.639 | 92.836 | 6.880 | 20.498 | 11,371 |

| TAT | 0.673 | 0.557 | 2.858 | 0.046 | 0.503 | 11,371 |

| GROWTH | 11.172 | 6.773 | 203.747 | −59.407 | 34.254 | 11,371 |

| NPM | 6.843 | 5.369 | 74.509 | −72.881 | 16.424 | 11,369 |

| AGE | 20.330 | 20.014 | 35.409 | 9.763 | 4.992 | 11,371 |

| ShrZ | 12.537 | 4.604 | 127.128 | 1.020 | 20.667 | 11,371 |

| BDS | 0.372 | 0.333 | 0.571 | 0.308 | 0.053 | 11,371 |

| AUDIT | 0.968 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.175 | 11,371 |

| LnASSET | 22.602 | 22.473 | 26.435 | 19.584 | 1.368 | 11,371 |

| LnSALARY | 5.221 | 5.195 | 7.267 | 3.469 | 0.725 | 11,371 |

| STATE | 0.556 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.497 | 11,371 |

| BETA | 1.060 | 1.085 | 2.252 | −0.179 | 0.482 | 11,371 |

| Variable | CRTA | CRTB | HXCSR | LEV | TAT | GROWTH | NPM | AGE | ShrZ | BDS | AUDIT | LnASSET | LnSALARY | STATE | BETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRTA | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| CRTB | 0.987 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| HXCSR | −0.199 *** | −0.184 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| LEV | −0.018 * | −0.030 *** | −0.027 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| TAT | −0.056 *** | −0.052 *** | 0.045 *** | 0.067 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| GROWTH | −0.048 *** | −0.039 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.024 ** | 0.060 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| NPM | −0.211 *** | −0.182 *** | 0.318 *** | −0.256 *** | −0.127 *** | 0.148 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| AGE | 0.019 * | 0.026 *** | −0.081 *** | 0.041 *** | −0.054 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.024 ** | 1.000 | |||||||

| ShrZ | −0.012 | −0.010 | 0.017 * | 0.071 *** | 0.031 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.005 | −0.093 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| BDS | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.025 *** | −0.023 ** | 0.005 | −0.017 * | −0.026 *** | −0.005 | 1.000 | |||||

| AUDIT | −0.286 *** | −0.277 *** | 0.143 *** | −0.105 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.172 *** | −0.065 *** | 0.019 ** | 0.004 | 1.000 | ||||

| LnASSET | −0.232 *** | −0.233 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.007 | 0.038 *** | 0.092 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.011 | 0.060 *** | 0.112 *** | 1.000 | |||

| LnSALARY | −0.147 *** | −0.137 *** | 0.240 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.139 *** | 0.217 *** | −0.119 *** | 0.021 ** | 0.091 *** | 0.472 *** | 1.000 | ||

| STATE | −0.108 *** | −0.115 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.172 *** | 0.054 *** | −0.108 *** | −0.026 *** | −0.056 *** | 0.207 *** | −0.023 ** | 0.060 *** | 0.230 *** | −0.069 *** | 1.000 | |

| BETA | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.041 *** | 0.076 *** | −0.031 *** | −0.019 ** | −0.018 * | −0.000 | 0.054 *** | −0.004 | −0.003 | 0.054 *** | 0.005 | 0.067 *** | 1.000 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| CRTA | CRTB | CRTA | CRTB | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | 5.876 (7.607) | 9.398 (7.763) | 8.182 (7.185) | 11.572 (7.391) |

| HXCSR | −0.019 *** (0.003) | −0.017 *** (0.003) | −0.117 *** (0.010) | −0.110 *** (0.010) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.001 *** (0.0001) | 0.001 *** (0.0001) | ||

| L.LEV | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.003 (0.008) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.002 (0.007) |

| L.TAT | −0.258 (0.288) | −0.355 (0.304) | −0.187 (0.281) | −0.288 (0.297) |

| L.GROWTH | −0.003 * (0.002) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.002 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.002) |

| L.NPM | −0.004 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) |

| AGE | −0.533 * (0.280) | −0.528 * (0.285) | −0.564 ** (0.262) | −0.557 ** (0.269) |

| ShrZ | 0.006 * (0.003) | 0.007 * (0.003) | 0.005 (0.003) | 0.006 * (0.003) |

| BDS | 1.386 (1.441) | 1.203 (1.516) | 1.062 (1.387) | 0.897 (1.465) |

| L.AUDIT | −1.426 *** (0.455) | −1.587 *** (0.486) | −1.293 *** (0.458) | −1.462 *** (0.489) |

| LnASSET | 0.436 ** (0.178) | 0.293 (0.189) | 0.420 ** (0.172) | 0.277 (0.183) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.056 (0.161) | −0.020 (0.169) | −0.034 (0.158) | 0.0002 (0.166) |

| STATE | 1.069 ** (0.523) | 1.022 * (0.546) | 0.931 * (0.495) | 0.892 * (0.522) |

| BETA | 0.207 ** (0.103) | 0.207 * (0.108) | 0.229 ** (0.102) | 0.227 ** (0.107) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 |

| Within_R2 | 0.059 | 0.052 | 0.088 | 0.075 |

| F_Value | 12.59 *** | 10.97 *** | 18.91 *** | 15.86 *** |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| HXCSR | HXCSR | HXCSR2 | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| CSR_ind | 0.848 *** (0.077) | 1.111 *** (0.230) | 36.035 * (18.429) |

| CSR_ind2 | −0.004 (0.004) | 0.439 (0.300) | |

| CSR_Region | 0.510 *** (0.045) | 0.142 (0.165) | −27.125 ** (12.605) |

| CSR_Region2 | 0.006 ** (0.003) | 1.069 *** (0.221) | |

| L.HXCSR | 0.398 *** (0.011) | 0.397 *** (0.011) | 30.272 *** (0.955) |

| # of obs. | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.424 | 0.424 | 0.397 |

| F_Value | 136.67 *** | 130.65 *** | 81.87 *** |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRTA | CRTB | CRTA | CRTB | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | 14.968 *** (1.027) | 16.019 *** (1.101) | 15.413 *** (1.031) | 16.466 *** (1.109) |

| HXCSR | −0.020 *** (0.005) | −0.020 *** (0.005) | −0.215 *** (0.060) | −0.216 *** (0.064) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.003 *** (0.001) | 0.003 *** (0.001) | ||

| L.LEV | 0.008 *** (0.003) | 0.007 ** (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| L.TAT | −0.229 ** (0.093) | −0.219 ** (0.099) | −0.040 (0.110) | −0.030 (0.117) |

| L.GROWTH | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| L.NPM | −0.015 *** (0.004) | −0.013 *** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) |

| AGE | 0.023 ** (0.009) | 0.028 *** (0.010) | 0.024 *** (0.009) | 0.029 *** (0.010) |

| ShrZ | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| BDS | 1.513 ** (0.721) | 1.619 ** (0.772) | 0.863 (0.732) | 0.968 (0.788) |

| L.AUDIT | −3.516 *** (0.417) | −3.785 *** (0.444) | −3.054 *** (0.434) | −3.323 *** (0.465) |

| LnASSET | −0.410 *** (0.044) | −0.459 *** (0.047) | −0.347 *** (0.048) | −0.396 *** (0.051) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.068 (0.075) | −0.028 (0.081) | 0.069 (0.084) | 0.109 (0.091) |

| STATE | −0.622 *** (0.082) | −0.685 *** (0.088) | −0.660 *** (0.081) | −0.723 *** (0.088) |

| BETA | 0.181 * (0.099) | 0.174 (0.106) | 0.181 * (0.097) | 0.174 * (0.104) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.148 | 0.139 | 0.186 | 0.167 |

| Wald_chi2 | 1029.42 *** | 989.13 *** | 1067.62 *** | 1019.22 *** |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRTA | CRTB | CRTA | CRTB | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | 14.879 *** (1.024) | 15.936 *** (1.099) | 15.433 *** (1.029) | 16.479 *** (1.107) |

| HXCSR | −0.020 *** (0.005) | −0.020 *** (0.005) | −0.224 *** (0.061) | −0.221 *** (0.064) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.003 *** (0.001) | 0.003 *** (0.001) | ||

| L.LEV | 0.008 *** (0.003) | 0.007 ** (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| L.TAT | −0.241 *** (0.092) | −0.232 ** (0.098) | −0.043 (0.110) | −0.036 (0.117) |

| L.GROWTH | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| L.NPM | −0.016 *** (0.004) | −0.014 *** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.006 (0.005) |

| AGE | 0.023 ** (0.009) | 0.028 *** (0.010) | 0.024 *** (0.009) | 0.028 *** (0.010) |

| ShrZ | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 * (0.002) |

| BDS | 1.578 ** (0.719) | 1.664 ** (0.771) | 0.825 (0.731) | 0.918 (0.788) |

| L.AUDIT | −3.524 *** (0.416) | −3.787 *** (0.444) | −3.011 *** (0.434) | −3.286 *** (0.465) |

| L.LnASSET | −0.406 *** (0.044) | −0.455 *** (0.047) | −0.342 *** (0.047) | −0.392 *** (0.051) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.065 (0.075) | −0.024 (0.081) | 0.071 (0.084) | 0.111 (0.091) |

| STATE | −0.619 *** (0.082) | −0.684 *** (0.088) | −0.656 *** (0.081) | −0.721 *** (0.088) |

| BETA | 0.175 * (0.099) | 0.168 (0.106) | 0.161 * (0.097) | 0.153 (0.104) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 | 8532 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.148 | 0.139 | 0.184 | 0.166 |

| Wald_chi2 | 1034.01 *** | 993.49 *** | 1069.19 *** | 1020.72 *** |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRTA | CRTB | CRTA | CRTB | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | 3.807 (6.960) | 7.347 (7.191) | 6.041 (6.458) | 9.457 (6.754) |

| HXCSR | −0.018 *** (0.003) | −0.016 *** (0.003) | −0.118 *** (0.010) | −0.111 *** (0.010) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.001 *** (0.0001) | 0.001 *** (0.0001) | ||

| L.LEV | 0.002 (0.007) | 0.001 (0.008) | 0.001 (0.007) | −0.001 (0.008) |

| L.TAT | −0.146 (0.284) | −0.233 (0.300) | −0.084 (0.276) | −0.175 (0.292) |

| L.GROWTH | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.002 (0.002) |

| L.NPM | 0.006 (0.005) | 0.008 (0.005) | 0.006 (0.005) | 0.007 (0.005) |

| AGE | −0.400 (0.250) | −0.397 (0.260) | −0.427 * (0.228) | −0.422 * (0.241) |

| ShrZ | 0.006 ** (0.003) | 0.007 ** (0.003) | 0.006 * (0.003) | 0.006 * (0.003) |

| BDS | 1.237 (1.455) | 0.999 (1.516) | 0.918 (1.400) | 0.698 (1.465) |

| L.AUDIT | −0.925 ** (0.436) | −1.050 ** (0.472) | −0.766 * (0.436) | −0.900 * (0.473) |

| LnASSET | 0.375 ** (0.175) | 0.232 (0.185) | 0.359 ** (0.169) | 0.217 (0.179) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.067 (0.162) | −0.033 (0.169) | −0.050 (0.159) | −0.017 (0.167) |

| STATE | 0.834 * (0.482) | 0.763 (0.496) | 0.680 (0.452) | 0.617 (0.469) |

| BETA | 0.247 ** (0.102) | 0.255 ** (0.106) | 0.266 *** (0.100) | 0.273 *** (0.105) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 8398 | 8398 | 8398 | 8398 |

| Within_R2 | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.081 | 0.068 |

| F_Value | 10.38 *** | 8.87 *** | 17.03 *** | 14.05 *** |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCRTA | MCRTB | MCRTA | MCRTB | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | −7.654 (8.095) | −3.061 (8.432) | −4.506 (7.715) | −0.108 (8.107) |

| HXCSR | −0.036 *** (0.005) | −0.034 *** (0.005) | −0.161 *** (0.016) | −0.151 *** (0.016) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.002 *** (0.0002) | 0.002 *** (0.0002) | ||

| L.LEV | 0.013 (0.011) | 0.013 (0.011) | 0.012 (0.010) | 0.012 (0.011) |

| L.TAT | −0.618 (0.382) | −0.809 ** (0.410) | −0.512 (0.373) | −0.710 * (0.402) |

| L.GROWTH | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) |

| L.NPM | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.003 (0.008) |

| AGE | −0.330 (0.245) | −0.297 (0.255) | −0.366 (0.231) | −0.331 (0.242) |

| ShrZ | 0.010 ** (0.005) | 0.011 ** (0.005) | 0.009 * (0.005) | 0.010 * (0.005) |

| BDS | 1.395 (2.189) | 1.156 (2.323) | 1.016 (2.140) | 0.801 (2.278) |

| L.AUDIT | −1.300 * (0.670) | −1.475 ** (0.705) | −1.128 * (0.668) | −1.314 * (0.705) |

| LnASSET | 0.832 *** (0.253) | 0.603 ** (0.269) | 0.798 *** (0.246) | 0.571 ** (0.263) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.552 ** (0.213) | −0.531 ** (0.226) | −0.516 ** (0.211) | −0.496 ** (0.224) |

| STATE | 1.696 ** (0.731) | 1.730 ** (0.772) | 1.563 ** (0.704) | 1.606 ** (0.748) |

| BETA | 0.067 (0.153) | 0.055 (0.160) | 0.071 (0.152) | 0.058 (0.159) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 9946 | 9946 | 9946 | 9946 |

| Within_R2 | 0.193 | 0.198 | 0.208 | 0.210 |

| F_Value | 60.05 *** | 62.39 *** | 55.89 *** | 58.53 *** |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCRTA3 | SCRTB3 | SCRTA5 | SCRTB5 | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | 0.009 (0.603) | 0.036 (0.597) | 0.060 (0.486) | 0.076 (0.482) |

| HXCSR | −0.014 ** (0.006) | −0.015 ** (0.006) | −0.013 *** (0.005) | −0.014 *** (0.005) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.002 ** (0.001) | 0.002 ** (0.001) | 0.002 *** (0.001) | 0.002 *** (0.001) |

| L.LEV | 0.001 ** (0.001) | 0.001 ** (0.001) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) |

| L.TAT | −0.054 ** (0.023) | −0.053 ** (0.023) | −0.045 ** (0.020) | −0.045 ** (0.020) |

| L.GROWTH | 0.002 (0.011) | 0.002 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.008) | 0.003 (0.008) |

| L.NPM | −0.005 (0.023) | −0.006 (0.023) | −0.013 (0.018) | −0.014 (0.018) |

| AGE | 0.042 * (0.022) | 0.040 * (0.022) | 0.027 (0.018) | 0.026 (0.017) |

| ShrZ | 0.001 * (0.000) | 0.001 * (0.000) | 0.001 ** (0.000) | 0.001 ** (0.000) |

| BDS | −0.270 ** (0.106) | −0.269 ** (0.106) | −0.196 ** (0.092) | −0.195 ** (0.091) |

| L.AUDIT | 0.014 (0.028) | 0.014 (0.028) | 0.012 (0.022) | 0.012 (0.022) |

| LnASSET | −0.024 * (0.013) | −0.024 * (0.013) | −0.012 (0.011) | −0.012 (0.011) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.017 (0.013) | −0.017 (0.013) | −0.015 (0.011) | −0.015 (0.011) |

| STATE | 0.047 (0.040) | 0.047 (0.040) | 0.028 (0.030) | 0.028 (0.030) |

| BETA | 0.006 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.009) | 0.008 (0.007) | 0.009 (0.007) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 9916 | 9916 | 9916 | 9916 |

| Within_R2 | 0.155 | 0.157 | 0.108 | 0.110 |

| F_Value | 26.13 *** | 26.50 *** | 17.09 *** | 17.40 *** |

| Variable | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| DER | DITAR | R&D | |

| Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | Coef. (S.E.) | |

| Intercept | −137.615 *** (16.853) | −89.598 *** (31.035) | 1.404 (3.511) |

| HXCSR | −0.195 *** (0.024) | −0.310 *** (0.042) | −0.034 *** (0.006) |

| HXCSR2 | 0.002 *** (0.0003) | 0.003 *** (0.0004) | 0.0004 *** (0.0001) |

| L.LEV | −0.013 *** (0.004) | ||

| L.TAT | 0.625 (0.910) | −5.654 *** (1.826) | −0.418 *** (0.135) |

| L.GROWTH | 0.037 (0.385) | 0.012 ** (0.006) | −0.007 *** (0.001) |

| L.NPM | −0.095 *** (0.011) | −0.096 *** (0.020) | 0.006 (0.004) |

| AGE | −0.703 (0.523) | −0.646 (0.955) | −0.032 (0.103) |

| ShrZ | 0.033 *** (0.010) | 0.040 *** (0.011) | −0.001 (0.002) |

| BDS | −3.200 (3.937) | −4.669 (6.817) | −0.711 (0.778) |

| L.AUDIT | −0.824 (1.188) | −3.205 (1.967) | −0.085 (0.209) |

| LnASSET | 8.902 *** (0.536) | 6.357 *** (1.142) | 0.168 (0.107) |

| L.LnSALARY | −0.963 ** (0.444) | −1.274 * (0.655) | 0.169 ** (0.073) |

| STATE | 0.930 (1.351) | 3.467 (2.401) | 0.229 (0.216) |

| BETA | −0.302 (0.300) | 0.329 (0.431) | 0.094 (0.062) |

| YEAR/IND | YES | YES | YES |

| # of obs. | 8024 | 9946 | 6906 |

| Within_R2 | 0.389 | 0.091 | 0.092 |

| F_Value | 120.69 *** | 5.67 *** | 17.08 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Liu, G.; Fu, Q.; Abdul Rahman, A.A.; Meero, A.; Sial, M.S. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010531

Li X, Liu G, Fu Q, Abdul Rahman AA, Meero A, Sial MS. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from Emerging Economy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010531

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiao, Gang Liu, Qinghua Fu, Abdul Aziz Abdul Rahman, Abdelrhman Meero, and Muhammad Safdar Sial. 2022. "Does Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from Emerging Economy" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010531

APA StyleLi, X., Liu, G., Fu, Q., Abdul Rahman, A. A., Meero, A., & Sial, M. S. (2022). Does Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 14(1), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010531