Technopreneurial Intentions: The Effect of Innate Innovativeness and Academic Self-Efficacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

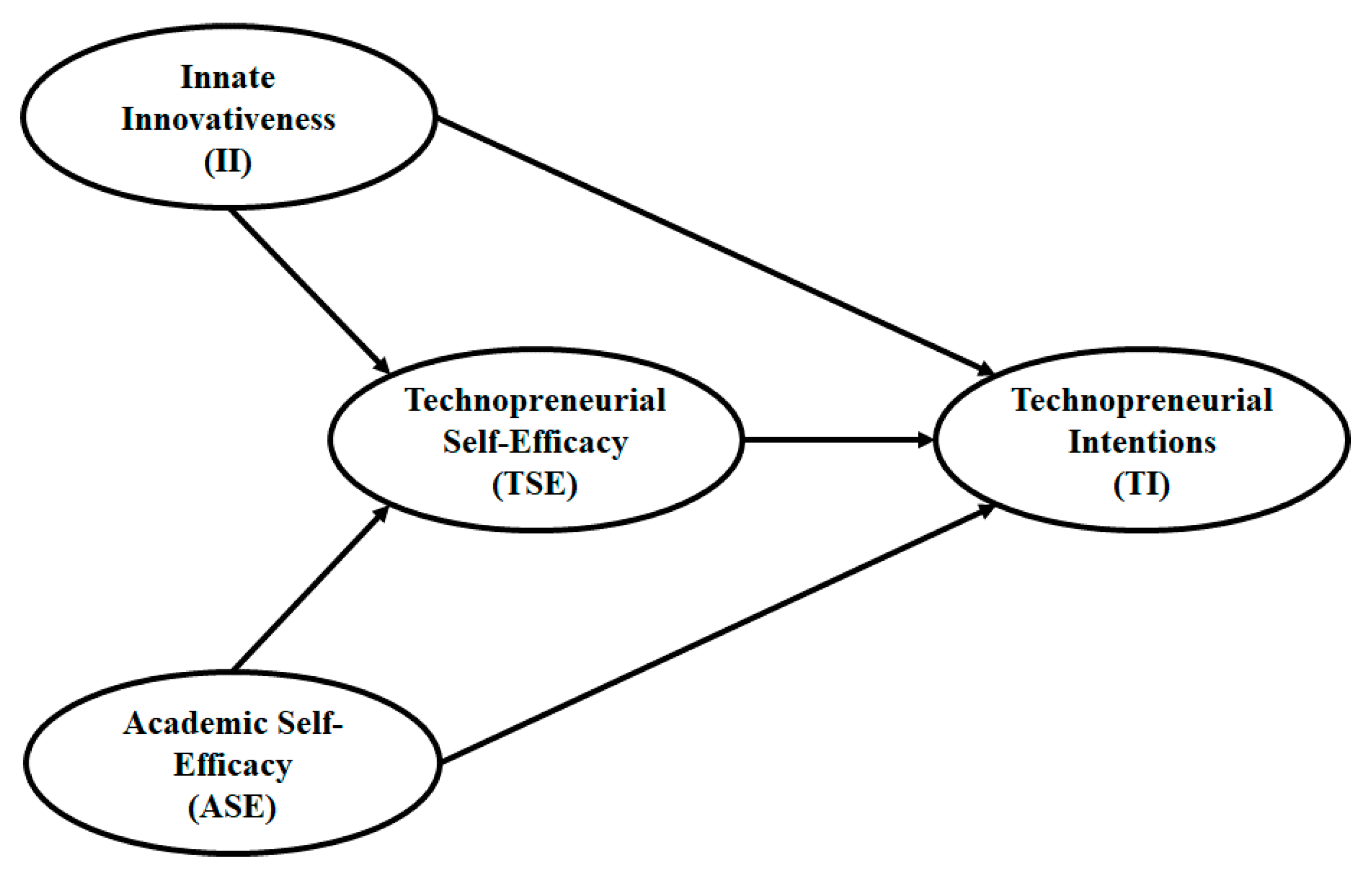

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Technopreneurial Intentions (TI)

2.2. Technopreneurial Self-Efficacy (TSE)

2.3. Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE)

2.4. Innate Innovativeness (II)

3. Research Method

3.1. Questionnaire

3.2. Participants & Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Measurement Model Analysis

3.3.2. Structural Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Further Research

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| TI: Technopreneurial Intentions | |

| TI1 | A career as a technopreneur (i.e., developing technology-based ventures) is attractive to me. |

| TI2 | If I had the opportunity and resources, I would like to start a technology-based business. |

| TI3 | People I care about would approve of my intentions to become a technopreneur. |

| TI4 | Most people who are important to me would approve of me becoming a technopreneur. |

| TI5 | Being a technopreneur gives me satisfaction. |

| TI6 | Being a technopreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages to me. |

| TI7 | Amongst various options, I would rather be a technopreneur. |

| TSE: Technopreneurial Self-Efficacy | |

| TSE1 | I show great aptitude for creativity and innovation. |

| TSE2 | I show great aptitude for leadership and problem-solving. |

| TSE3 | I can develop and maintain favorable relationships with potential investors interested in new technology-based innovations. |

| TSE4 | I can see new market opportunities for new technology-based products and services. |

| TSE5 | I can develop a working environment that encourages people to try out something new. |

| II: Innate Innovativeness | |

| II1 | I am generally cautious about accepting new ideas. (r) |

| II2 | I rarely trust new ideas until I can see whether the vast majority of people around me accept them. (r) |

| II3 | I am aware that I am usually one of the last people in my group to accept something new. (r) |

| II4 | I am reluctant about adopting new ways of doing things until I see them working for people around me, (r). |

| II5 | I find it stimulating to be original in my thinking and behavior. |

| II6 | I tend to feel that the old way of living and doing things is the best way. (r) |

| II7 | I am challenged by ambiguities and unsolved problems. |

| II8 | I must see other people using new innovations before I will consider them. (r) |

| II9 | I am challenged by unanswered questions. |

| II10 | I often find myself skeptical of new ideas. (r) |

| ASE: Academic Self-Efficacy | |

| ASE1 | Regarding my studies, I am able to deal with difficult situations and requirements, if I make an effort. |

| ASE2 | I find it easy to understand new content/topics in my studies. |

| ASE3 | When I am supposed to talk about a difficult subject in front of the seminar group, I think I can do it. |

| ASE4 | Even if I am sick for a longer period of time, I can still achieve a good outcome in my studies. |

| ASE5 | Even if the instructor doubts my competence, I am still sure I will perform well. |

| ASE6 | I am sure that I can still achieve my desired outcome even if I get a bad grade. |

References

- Dutta, N.; Meierrieks, D. Financial Development and Entrepreneurship’, International Review of Economics & Finance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 73, pp. 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, A.A. The Necessity of Engineering Entrepreneurship Education for Developing Economies. Int. J. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2009, 3, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Moaveni, S. Engineering Fundamentals. In An Introduction to Engineering, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Habash, R. Green engineering. In Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkimurto-Koivumaa, S.; Belt, P. About, for, in or through entrepreneurship in engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Edu. 2016, 41, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagvall Svensson, O.; Adawi, T.; Lundqvist, M.; Williams Middleton, K. Entrepreneurial engineering pedagogy: Models, tradeoffs and discourses. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 45, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Kamovich, U.; Longva, K.K.; Steinert, M. Combining technology and entrepreneurial education through design thinking: Students’ Reflections on the Learning Process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 164, 119689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowosire, R.A.; Elijah, O.; Fowosire, R. Technopreneurship: A view of technology, innovations and entrepreneurship. Glob. J. Res. Eng. 2017, 17. Available online: https://globaljournals.org/GJRE_Volume17/5-Technopreneurship-A-View-of-Technology.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Hoque, A.S.M.M.; Awang, Z.B.; Siddiqui, B.A. Technopreneurial Intention among University Students of Business Courses in Malaysia: A Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Entrep. Small Medium Enterp. 2017, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R.D.; Peters, M.P.; Sepherd, D.A. Enterprenuership; Mc Graw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D.A. Entrepreneurship education: Can business schools meet the challenge? Educ. Train. 2004, 46, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, F.; O’Connor, A.; Kuratko, D.F. Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Wennekers-Thurik1999_Article_LinkingEntrepreneurshipAndEcon. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. The emergence of entrepreneruship education-Luratko, 2005. Sage Publ. J. 2005, 29, 577–597. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00099.x?journalCode=etpb (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Fernandes, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Raposo, M.; Sanchez, J.; Hernandez–Sanchez, B. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: An international cross-border study. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 10, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Hills, G.E.; Seibert, S.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. In The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Wong, P.K.; Foo, M.D.; Leung, A. Entrepreneurial intentions. The influence of organizational and individual factors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, E.R. Entrepreneurial Intent and Development Reliable Metric, Entrepreneurship. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 669–695. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1396451 (accessed on 19 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Singhry, H.B. The Effect of Technology Entrepreneurial Capabilities on Technopreneurial Intention of Nascent Graduates. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 7, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yordanova, D.; Filipe, J.; Coelho, M.P. Technopreneurial Intentions among Bulgarian STEM Students: The Role of University. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Czasch, C.; Flood, M.G. From Intentions to Behavior: Implementation Intention, Commitment, and Conscientiousness. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1356–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, N.K. Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the U.S.A. and Turkey. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wickham, P.A. Strategic Entrepreneurship. In A Decision Making Approach to New Venture Creation and Management, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Molino, M.; Dolce, V.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C. Personality and social support as determinants of entrepreneurial intention. Gender differences in Italy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, R.; Neergaard, H.; Linstad, A.K. Understanding the Entrepreneurial Mind. In Understanding the Entrepreneurial Mind; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.E.; Peterson, M.; Mueller, S.L.; Sequeira, J.M. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: Refining the Measure. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Noble, A.; Jung, D.; Ehrlich, S. Entrepreneurial self efficacy. In The Development of a Measure and Its Relationship to Entrepreneurial Action, in Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research; Babson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, B. A gender perspective on career preferences and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Honicke, T.; Broadbent, J. The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, S.M.; MacDonald, S. Using Past Performance, Proxy Efficacy, and Academic Self-Efficacy to Predict College Performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 2518–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemers, M.M.; Hu, L.-T.; Garcia, B.F. Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F.; Schunk, D. Self-beliefs in psychology and education. In An Historical Perspective; Aronson, J., Ed.; Improving Academic Achievement; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, V.S.; Gusavac, N.; Hamann, T.; Felch, J.; Johnson, J.; Lamborn, S.; Torres, J. The Adaptive Success Identity Plan (ASIP): A Career Intervention for College Students. Career Dev. Q. 1998, 47, 48–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenollar, P.; Román, S.; Cuestas, P.J. University students’ academic performance: An integrative conceptual framework and empirical analysis. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, D.F.; Dowling, G.R. Innovativeness: The Concept and Its Measurement. J. Consum. Res. 1978, 4, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C. Innovativeness, Novelty Seeking, and Consumer Creativity. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Foxall, G.R. The Measurement of Innovativeness. Int. Handb. Innov. 2003, 5, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M.; Ter Hofstede, F.; Wedel, M. A Cross-National Investigation into the Individual and National Cultural Antecedents of Consumer Innovativeness. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.; Mason, C.H.; Houston, M.B. Does innate consumer innovativeness relate to new product/service adoption behavior? The intervening role of social learning via vicarious innovativeness. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiaku, O.C.; Nkamnebe, A.D.; Nwaizugbo, I.C. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among young graduates: Perspectives of push-pull-mooring model. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doanh, D.C.; Doanh, D.C.; Bernat, T.; Bernat, T. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention among vietnamese students: A meta-analytic path analysis based on the theory of planned behavior. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 2447–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Freiden, J.B.; Eastman, J. The generality/specificity issue in consumer innovativeness research. Technovation 1995, 15, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallister, J.G.; Foxall, G.R. Psychometric properties of the Hurt–Joseph–Cook scales for the measurement of innovativeness. Technovation 1998, 18, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, L.; Brouwer, J.; Jansen, E.; Crayen, C.; Hannover, B. Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students’ integration in academic and social support networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 62, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Duval-Couetil, N. What Drives Engineering Students To Be Entrepreneurs? Evidence of Validity for an Entrepreneurial Motivation Scale. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, S.K.; Thompson, M.E.; Morton, E.; Jin, Q.; Chen, H.L.; Colby, A.; Sheppard, S.D. Entrepreneurial intent of engineering and business undergraduate students. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 108, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, J.; Sun, J.; Bell, R. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 19, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, N.; Menascé, D.A. Student Perceptions of Engineering Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 95, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, A.; Kolvereid, L. Education in entrepreneurship and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R. Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.; Moberg, K. Improving perceived entrepreneurial abilities through education: Exploratory testing of an entrepreneurial self efficacy scale in a pre-post setting. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Count | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 246 | 65% |

| Female | 132 | 35% |

| Engineering Major: | ||

| Industrial | 53 | 14.02% |

| Mechanical | 56 | 14.81% |

| Electrical | 51 | 13.49% |

| Computer | 54 | 14.29% |

| Chemical | 55 | 14.55% |

| Civil | 57 | 15.08% |

| Chemical | 52 | 13.76% |

| Total | 378 |

| Construct, Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI: Technopreneurial Intentions | 0.935 | 0.937 | 0.684 | |

| TI1 | 0.633 | |||

| TI2 | 0.841 | |||

| TI3 | 0.942 | |||

| TI4 | 0.904 | |||

| TI5 | 0.938 | |||

| TI6 | 0.786 | |||

| TI7 | 0.793 | |||

| TSE: Technopreneurial Self-Efficacy | 0.939 | 0.940 | 0.758 | |

| TSE1 | 0.841 | |||

| TSE2 | 0.943 | |||

| TSE3 | 0.904 | |||

| TSE4 | 0.920 | |||

| TSE5 | 0.824 | |||

| II: Innate Innovativeness | 0.928 | 0.929 | 0.621 | |

| II1 | 0.759 | |||

| II2 | 0.806 | |||

| II3 | 0.781 | |||

| II4 | 0.831 | |||

| II5 | 0.797 | |||

| II6 | 0.823 | |||

| II7 | 0.838 | |||

| II8 | 0.883 | |||

| II9 | 0.006 | |||

| II10 | 0.045 | |||

| ASE: Academic Self-Efficacy | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.646 | |

| ASE1 | 0.697 | |||

| ASE2 | 0.833 | |||

| ASE3 | 0.887 | |||

| ASE4 | 0.879 | |||

| ASE5 | 0.916 | |||

| ASE6 | 0.804 |

| II | TI | ASE | TSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | 0.788 | |||

| TI | 0.370 | 0.827 | ||

| ASE | 0.495 | 0.466 | 0.804 | |

| TSE | 0.250 | 0.607 | 0.368 | 0.871 |

| Index | Value Obtained | Recommended Values |

|---|---|---|

| IFI | 0.949 | ≥0.90 |

| RFI | 0.900 | ≥0.90 |

| CFI | 0.949 | ≥0.90 |

| NFI | 0.910 | ≥0.90 |

| NNFI (TLI) | 0.943 | ≥0.90 |

| RMSR | 0.100 | ≤0.11 |

| RMSEA | 0.061 | <0.10 |

| Hypothesis | Model | Std. Regression Coef. | Two-Tailed Significance Level p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | TSE → TI | 0.513 * | 0.012 |

| H2 | ASE → TI | 0.234 * | 0.001 |

| H3 | ASE → TSE → TI | 0.168 * | 0.001 |

| H4 | II → TI | 0.153 * | 0.012 |

| H5 | II → TSE → TI | 0.053 | 0.135 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salhieh, S.M.; Al-Abdallat, Y. Technopreneurial Intentions: The Effect of Innate Innovativeness and Academic Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010238

Salhieh SM, Al-Abdallat Y. Technopreneurial Intentions: The Effect of Innate Innovativeness and Academic Self-Efficacy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010238

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalhieh, Sa’Ed M., and Yousef Al-Abdallat. 2022. "Technopreneurial Intentions: The Effect of Innate Innovativeness and Academic Self-Efficacy" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010238

APA StyleSalhieh, S. M., & Al-Abdallat, Y. (2022). Technopreneurial Intentions: The Effect of Innate Innovativeness and Academic Self-Efficacy. Sustainability, 14(1), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010238