1. Introduction

Healthcare service facilities contribute to the control, prevention, and treatment of diseases and so represent an important dimension of sustainability. The health sector in any country consumes a significant part of financial and human resources, thus reflecting the economic dimension of sustainability. Consequently, healthcare organizations consume a significant amount of material and inevitably create waste, which affects environmental sustainability [

1,

2]. Addressing healthcare waste not only significantly creates a considerable number of benefits to the environment but also contributes to cost saving and improves the public image of the parties involved [

3,

4].

Healthcare wastes usually result from the provision of medical care and its associated support services, such as nutrition and maintenance. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 15% of healthcare waste is estimated to be hazardous medical waste (HMW), such as infectious, radioactive, or pathological materials, while the vast majority of waste is considered municipal solid waste (MSW), such as that coming from households in the form of food, paper, and plastic [

5]. Internationally, the generation of healthcare waste has increased significantly due to population growth and the concomitant increase in the number of healthcare facilities [

6]. Such development has created an environmental and economic burden on countries around the world. According to Zimmer and McKinley, healthcare waste is the fourth-largest contributor of mercury in the environment, and managing MSW and HMW costs USD 0.05 and USD 1.25 a pound, respectively [

7].

Due to the economic and environmental impacts of waste, early debates on the health industry and its sustainability have mostly focused on waste elimination and recycling as critical strategies for health systems that promote environmentally friendly practices. This is the main objective of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), whose aim is to ensure a sustainable future for all by creating a balance between social, economic, and environmental development and improving system performance by meeting current and future stakeholders needs [

8,

9]. The growth of environmental awareness and the development of robust regulation, coupled with the current need to reduce public spending, have all accentuated environmental issues for the health sector. Therefore, developing and implementing sustainable healthcare waste management requires a holistic approach involving a range of parties, including policymakers, government and non-government organizations, and the community [

2,

10,

11,

12].

With regard to healthcare management within healthcare organizations, several studies have highlighted environmental measures for resource use minimization and waste reduction. However, few studies have used a holistic approach that includes the political, organizational, and individual attempts toward sustainable waste management. This paper focuses on the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health’s (MOH) waste management system as a case study, with the main objective of reviewing the status of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the country’s alignment with its Vision 2030. The Saudi government is aiming to achieve environmental sustainability by preserving natural resources and increasing the efficiency of waste management [

13]. In this respect, the country provides an excellent research context to explore the extent to which the sustainability objectives are being translated into practice. Therefore, this paper set out (1) to explore the key factors that determine healthcare waste sustainability by applying a holistic methodology and (2) to suggest recommendations for improving the waste management system.

2. Materials and Methods

Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the Arabian Gulf as well as the Middle East, with a territory of 2,149,690 km

2. The country is a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) along with Oman, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Kuwait. The capital of Saudi Arabia is Riyadh, where this study was conducted [

14]. In Saudi Arabia, the MOH is considered the main healthcare provider, with 284 hospitals and 2390 primary healthcare (PHC) clinics [

15]. Riyadh was selected for this study as it is the business center of the country where all ministries and main waste management institutions, as well as 20% of the total healthcare facilities, are situated. According to the latest statistics, there are 17 government hospitals, 37 private hospitals, 125 government primary care centers, and 818 private clinics in Riyadh [

16].

To assess the sustainability of waste production and consumption, it is best to follow a multidisciplinary approach to collect information so as to incorporate different data perspectives [

17]. Therefore, this study used a combination of four different research methods in order to gather data and explore the opportunities and challenges in healthcare waste management:

Analyzing all existing official documents about healthcare waste policies and procedures in Saudi Arabia;

Undertaking a rapid assessment observation of healthcare waste management policies and practices;

Conducting semi-structured interviews of key informants in health waste management;

Convening a focus group with healthcare practitioners.

2.1. Document Analysis of National Policy, Regulations, and Other Information

The macro level of health waste management in Saudi Arabia was first assessed by analyzing relevant existing documents, including guidelines and laws concerning health waste management and background information about health waste records and statistics. Given that the published policy documents were not indexed or listed in any academic databases in a standardized and timely manner, the data search began with an examination of the gray literature: government and mass media websites. To increase the number of documents and ensure reliability, we expanded the scope of the search for information to the GCC Health Council and the WHO, as these organizations are the most globally recognized ones that report information regarding healthcare waste. In addition, a literature search for academic papers on healthcare waste management in Saudi Arabia was conducted on Web of Science databases using the following keywords: waste, hazardous, healthcare waste, hospital waste, medical waste, clinical waste, environmental management, legislation, policies, KSA, Saudi Arabia, and GCC countries. These were separate from the official policy documents about HCW. National and local reports, guidelines, and national conference reports were also examined.

Most of the documents were collected from official governmental websites; however, some statistics were not easily identified through online data searches and were collected through interviews of governmental officers. Following the principles of the framework synthesis approach [

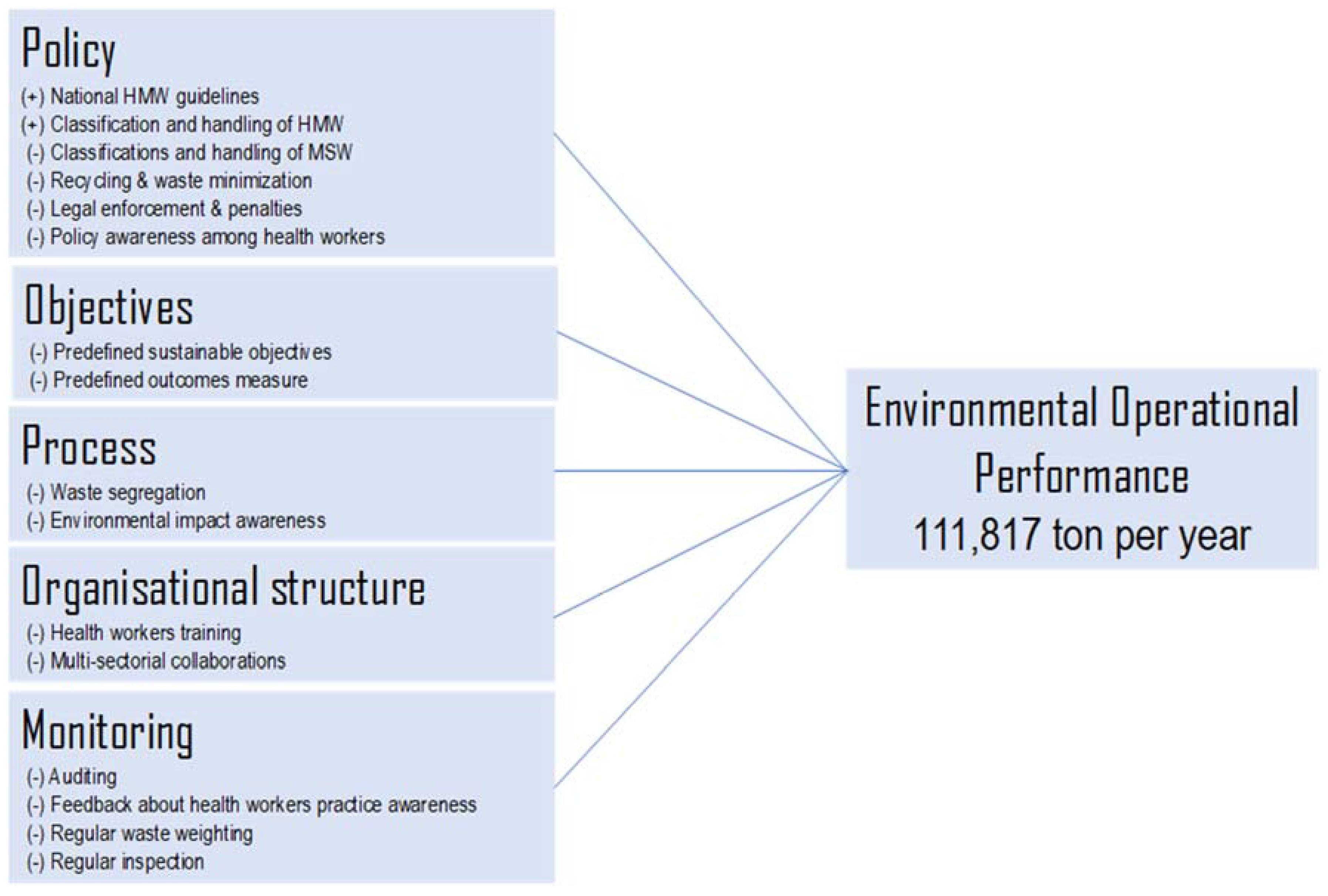

18], we deductively extracted, summarized, and synthesized data obtained from the documents according to the corporate environmental performance framework that conceptualizes sustainable performance into five environmental management performance elements (inputs: policy, objectives, processes, organizational structure, and environmental monitoring) and environmental operational performance (outcomes). Policy constitutes a macro-level commitment and responsibility toward the improvement of environmental operational performance. Objectives refer to specific environmental goals and targets in order to translate environmental policy into action. Processes refer to actions designed to improve environmental operational performance. The organizational structure refers to the formal organizational structure implemented to achieve environmental goals. Environmental monitoring refers to corrective actions and procedures that ensure continuous improvement of environmental operational performance. [

19]. The focus was only on waste as one of the framework’s sustainable environmental performance indicators. This framework was considered a useful one for the study, hence its selection.

2.2. Rapid Assessment of Healthcare Waste (Observation)

Observation of the health waste management process was assessed by adapting and modifying the healthcare waste management tool for rapid assessment [

20]. The checklist includes 6 criteria of waste management practice and 21 indicators. The tool ranks the performance of each criterion by the level of sustainability ranging from 0 (operating in a totally unsustainable manner with reluctance to change) to 4 (operating in a way that displays all the characteristics normally associated with sustainable development) (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

2.3. Semi-Structured Interview of Key Informants

To identify the challenges and opportunities in improving the sustainability of healthcare waste management, semi-structured interviews were conducted with some of the main parties involved in healthcare waste management in Saudi Arabia. The main stakeholders were identified by reviewing official documents in the first phase of the study, and then their number was supplemented by new participants by applying the snowballing technique [

21]. There were finally a total of 12 interviewees: 3 from the MOH, 2 from private waste management companies, 3 environmentalists working with public authorities, and 4 academics working in the field of healthcare waste management.

2.4. Focus Group with Healthcare Providers

A focus group session was conducted in one of the largest hospitals in Riyadh, in which 10 healthcare workers, considered critical parties in healthcare waste management, were brought together as a group. They included physicians, nurses, laboratory specialists, dieticians, and a receptionist. Half of them were males, and the age ranged between 26 and 51 years. To ensure that participants could speak openly about the issues, persons who worked in the environmental department were excluded. The session lasted for 40 min and was conducted in a conversational style. The main questions were developed based on the data gathered during the documentary analysis and interviews. The discussion covered waste minimization, rules and regulations, and the training received on waste disposal. All participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential and would have no influence on their work evaluation. The focus group was convened, audiotaped, and transcribed by the researcher with the name of the participants and the hospital coded for confidentiality.

2.5. Data Triangulation

This study adopted a multi-method approach, where the data were collected and analyzed independently. Therefore, triangulation was used to integrate overlapping of the multi-method findings, according to Brewer and Hunter [

22] (

Figure 1). For example, the focus group provided a snapshot of the healthcare workers’ attitude toward waste segregation, document analysis and observation showed the outcome of their behavior, and the interviews gave a broader view of the strategies that could be adopted by the policymakers. This study synthesized the findings according to the health service levels: macro (policy), meso (healthcare organization), and micro (individuals).

3. Results

3.1. Macro Level: Analysis of Regulation, Guidelines, and National Data

The definition of the healthcare waste policy, regulations, and standard system began about two decades ago. In 1998, the Saudi MOH passed regulations defining HMW handling, treatment, and disposal. One year later, the GCC endorsed a unified HMW regulation among all Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia. Since the waste management national policy was developed, it has been revised twice, in 2005 and 2019 [

23,

24,

25]. During the interviews, the participants mentioned four main policymaking parties: the MOH, the Ministry of Environmental Water and Agriculture, the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, and private waste management companies. All participants agreed that there was a need for a legal framework to enhance the level of coordination among these parties. An environmentalist in an academic job said:

“The Ministry of Environment has specific legal requirements about medical waste, but due to the lack of coordination between it and the other parties, it is not sufficiently monitored.”

The Saudi government recognized the need for a regulatory body to enhance the multisectoral collaboration between all the waste management parties, including those involved in healthcare waste in the country. Therefore, the Saudi Waste Management Center (SWMC) was established in May 2019 to organize and supervise waste management regulations and practices. In this organization, the representatives on the center’s board came from different ministries, namely those for the environment, rural affairs, economy, health, and energy, as well as a representative from the general investment’s authority [

26]. The national healthcare waste plans and initiatives are presented in a time line in

Figure 2.

To explore the sustainability of healthcare waste management at the macro level, we adopted a modified version of the elements of the organizational environmental performance framework [

19]. With regard to the first framework input element (policy), the national policy classified HMW into eight groups: infectious, pathological, sharp, pharmaceutical, chemical, genotoxic, radioactive, and pressurized containers. The existing HMW policy also covered waste collection, storage, transportation, treatment, and disposal practices. However, the classification and management of MSW were totally absent from the policy statements. In addition, the policy did not state any sustainable targets or objectives in terms of outcome measures that should be achieved by healthcare facilities [

25]. With regard to the third element (process), document analysis showed that Saudi healthcare waste is affected by practical obstacles such as a lack of awareness on the part of health workers of the HMW color code, segregation, disinfection, and storage. This was evident both in hospitals [

27,

28,

29] and among PHC workers [

30,

31].

With regard to organizational structure, document analysis and focus group results revealed that to achieve sustainable management of healthcare waste, there is a need to strengthen the role of the health worker. This could be done by the workers improving their sustainable environmental practices and them being made aware, through training, of the environmental impact of their work. Furthermore, multisector collaboration between the MOH and other parties in Saudi Arabia should be considered [

27,

29,

31,

32]. During the focus group, the health workers suggested that training on waste handling should be a requirement for renewing their professional licenses. According to one health worker:

“I had medical waste training in the first year of my work in the hospital. I think if there was regular training on general waste sorting, like paper and plastic, and if we made this training a requirement to renew the professional license, we will increase the level of waste sustainability in the hospital.”

Auditing (or environmental monitoring) is the final key input element of the environmental sustainability framework. Both document analysis and direct observations revealed the absence of waste audit practices, inspections, waste weighing, and a continuous feedback and communication channel between the different parties [

29,

32].

All the above-mentioned elements are responsible for environmental sustainability and enhancement of the operational performance of the environment (

Figure 3). To obtain a comprehensive picture of the production of healthcare waste on a national level, the latest data were extracted from monitoring records and mapped with the healthcare facilities and services in each region of the country (

Appendix A). The official statistical data report was from the MOH, and the value of the data covers the period from January to December 2018. The data were obtained from the environmental health department where waste was segregated daily based on its source and weighed before disposal at the landfill site. The data reflected the weight of the HMW taken from all the hospitals and PHC clinics around the country. The total estimated HMW produced by hospitals and PHC clinics were 21,016 and 1347 tons per year, respectively. However, no weighing or reliable estimations were available for the MSW produced. Giving the fact that only 15 to 20% of the total healthcare waste is hazardous [

5], the MSW estimated for all hospitals and PHC clinics, based on 80% of the available data, was 84,064 and 5390 tons per year, respectively (

Table 3). To enable a global comparison, we also estimated the waste per bed and per visit. Given the fact that the bed occupancy rate in Saudi Arabia was 77% [

15], according to the secondary data provided by the MOH, the estimated HMW and MSW for hospitals were 1.7 and 6.8 kg/bed/day, respectively, and those for PHC clinics were 0.029 and 0.116 kg/visit, respectively (

Table 3).

To estimate the MSW composition in Saudi Arabia, the waste was calculated in accordance with MSW values from hospitals in Kuwait [

33]. In addition to the data source reliability, this study was selected for two reasons. First, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are similar countries in terms of their health system operational capacity. The ratio of physicians per 1000 population was 2.64 for Saudi Arabia and 2.61 for Kuwait, and that of hospital beds per 1000 population was 2.04 for Saudi Arabia and 2.24 for Kuwait [

34]. Second, Kuwait belongs to the Gulf States and is governed by the Healthcare Waste Act, in line with other GCC countries, so this study was considered appropriate for guiding our estimations [

25] (

Table 4).

3.2. Meso Level: Healthcare Organization

Observations and interviews of key informants revealed sufficient budgetary allocation for HMW management, where waste was collected and segregated in different types of receptacles by dedicated staff. However, the hospital lacked a clear policy. Furthermore, as confirmed previously in document analysis, training only covered hazardous waste handling, and there was no form of color coding and segregation of the MSW. Due to the unclear policy and inadequate sustainable waste handling guidelines, healthcare facilities lacked monitoring, even as our observation confirmed that waste weighing was not regularly conducted.

With regard to recycling, direct observations, interviews, and the focus group showed that there was no form of MSW recycling or reuse. All wastes were treated by a purpose-built waste treatment plant and disposed of in engineered landfill sites, where the waste was handled by alternative technology. According to the participants, waste recycling was identified as a primary opportunity for the Saudi national system. One of the participants at a high senior position in the MOH said:

“The Kingdom is heading towards achieving sustainable development. Recycling is the future trade for Saudi Arabia.”

Several other participants shared the same view about healthcare waste recycling:

“Waste is a fortune, and proven by global experiences, as it is a great economic return. If we recycle waste, we will achieve two goals: reduce burial and recover part of the cost of these materials.”

“Large industries will be based on recycling, and will reduce the cost of waste collection, transportation and disposal.”

According to our rapid assessment scores achieved by triangulating our observations with qualitative answers to ensure consistency, the level of sustainability of the hospital waste management system was considered at level 2. This means that the healthcare waste management system of the hospital was operating in a manner consistent with some aspects considered sustainable in terms of waste storage and disposal and other aspects considered unsustainable, especially in waste recycling, as seen in

Table 5.

3.3. Micro Level (Individuals)

The interviews and focus group revealed that the participants identified social responsibility as a main challenge in achieving environmental sustainability.

Table 6 presents the identified dimensions of social responsibility.

The participants believed that the Saudi policymakers faced a huge challenge in achieving sustainable waste management, and they suggested that there was a need to strengthen social responsibility through education and increased awareness among healthcare workers and the community. One of the participants in an academic job said:

“Through my academic research, I found that the level of social responsibility here in Saudi Arabia in dealing with waste in general is unsatisfactory.”

The participants believed that the need for awareness was a key factor for enhancing social responsibility, as said by one of the medical waste workers:

“We will achieve the optimal level of social responsibility if the society is aware of the great economic return and the clean environment that comes from sustainable waste practice.”

The Saudi policymakers recognized the need to increase the value of social responsibility in the community. Document analysis showed that the Saudi Ministry of Environment recently updated the general environmental regulation in 2020 and added the following statement: “Raise the awareness of environmental issues, instill a sense of individual and collective social responsibility to preserve and improve it, and encourage national volunteer effort in this field” [

26].

Raising awareness was strongly emphasized in the documents analyzed, and one of the participants suggested:

“The most important challenge is the culture of society, the information dissemination methods must be changed, dependence on educational posters is insufficient, and so it must attract the individual’s eye through the channels that he follows such as social media platforms.”

Suggestions for healthcare waste management practices were not limited to healthcare providers; one of the environmental department managers complained:

“Medical waste does not exist only inside of healthcare institutions. Do not forget that there is dangerous hazardous waste in homes and this must be disposed of in a safe way. Unfortunately, we do not have strict legislation to sort the household waste and dispose of medical waste in a safe way.”

Generally, the main challenge toward sustainable healthcare waste practices was individual and community awareness and a sense of social responsibility. Document analysis and interviews showed that the government still faces key challenges in achieving its new environmental goals. Raising social awareness requires the cooperation of various sectors as well as the sharing of information between the parties concerned. The focus group concluded that the dissemination of information about the environmental and financial benefits of sustainable practices could motivate individuals toward more positive sustainable behaviors.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to provide a comprehensive picture of the sustainability of healthcare waste management in Saudi Arabia. Adopting a multi-method approach combining primary and secondary data showed a lack of studies on the subject from a more holistic perspective. While nine national and regional policy documents mentioned healthcare waste, this study found that these documents were limited in scope, as only one document addressed four of five environmental sustainability framework elements [

29]. Overall, the documents largely ignored the fact that the sustainability of healthcare waste management has specific features regardless of whether it is related to policies, organizations, or individuals [

23,

25,

27,

28,

30,

31,

32,

35]. There are a number of challenges facing the sustainability of the Saudi waste management system, including the lack of a legal framework, limited training on sustainable management practices, a lack of coordination among key stakeholders, and the absence of social responsibility. All these challenges pose significant obstacles to the waste management system’s sustainability in Saudi Arabia and are linked to the macro, meso, and micro levels.

At the national level, Saudi Arabia’s healthcare facilities produce a large quantity of healthcare waste and consume just as much natural materials. The country’s estimated HMW and MSW were 22,000 and 98,000 tons/year, respectively. However, these figures seemed acceptable for Saudi Arabia as they were the same as those for other countries with similar economic conditions [

6,

36]. With regard to the consumption of natural resources, Saudi government hospitals across the country, every year, throw away in landfills paper (27,000 tons), plastic (15,000 tons), food (10,000 tons), glass (8000 tons), and metal (7000 tons). Regrettably, all these tons of materials end up in landfills without any form of recycling. From the perspective of sustainability, it seems that Saudi Arabia, through its advanced landfill HMW management system, is moving toward achieving enhanced life on land (SDG15) and good health and well-being (SDG03), two of the Sustainable Development Goals. However, there are still opportunities for stakeholders to meet the challenges in managing MSW and reaching responsible consumption and production (SDG12). By so doing, the country will achieve economic growth (SDG08), which is another main Sustainable Development Goal [

9]. From a political point of view, it is important to develop a coordinated policy that balances the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of the healthcare waste management system [

37]. This can be achieved by creating a legislative organization that mobilizes and unifies the practices of all the parties involved in the healthcare waste industry in order to create a shared vision for sustainable development in the country.

Much of the national unsustainability of the healthcare waste system can be traced to matters relating to policy, objectives, processes, organizational structure, and environmental monitoring [

19]. Internationally, healthcare waste is regulated either through ordinance or a specific policy [

38]. According to Ali et al. and other researchers, a specific policy for healthcare waste is considered a recent phenomenon in most developing countries; therefore, there are still many shortcomings regarding waste practices [

6,

12,

39]. This seems to be the case in Saudi Arabia, too, so a proper waste management policy is needed for the country to achieve economic and environmental sustainability. Our results also emphasize the need for the country to extend its policy beyond healthcare institutions. In addition, the national policy objectives must be developed within the context of sustainability and in a comprehensive manner that will align the mission and vision statements of healthcare organizations with those values entrenched at the organizational level. With regard to the process, we noted an inconsistency between the highly clarified HMW policy at the macro level and operational process at the meso level. Although the policy demands that HMW be collected separately and be regulated under GCC hazardous waste regulations (Articles 4 and 5), both document analysis and observations revealed an ignorance of the policy and procedures [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. However, healthcare waste malpractice is not limited only to Saudi Arabia but is also noted in other developed and developing countries [

6,

11,

12,

39,

40].

All the above-mentioned inconsistencies might be due to the lack of an organizational structure in terms of a merger of the political will, public engagement, and multi-sectorial collaboration [

23]. Saudi policymakers recognize that the gap in translating policy into practice is the result of the hierarchical waste governance system in the country. Therefore, the government recently established the SWMC as a new institutional framework to organize and make legislation for the management of all types of wastes across all parties involved, including different ministries and organizations. The presence of this new legislative institution opens the door for innovative initiatives that could lead the medical waste management process toward a more sustainable performance. This would then ensure the cooperation of all stakeholders, the health of the environment, and the strengthening of the role of community. In fact, the social dimension deserves more attention, as seen in a developing country like Brazil, where Scavard and colleagues proposed a new healthcare waste management framework tailored to the country’s cultural and economic context. This required establishing educational programs and empowering the community in its role. This initiative not only resulted in the enhancement of environmental management sustainability but also improved the population’s quality of life [

41].

With regard to monitoring of environmental issues, although the MOH invested in the technical and financial aspects of the process as well as staffing and landfilling procedures, waste training and recycling received scant attention among healthcare workers. With the attention focused mainly on waste personnel, it is crucial that all healthcare providers be involved. For example, in Vietnam, the involvement and commitment of all healthcare workers through the training programs achieved positive results in terms of the overall monitoring system [

42]. It seems that that the Saudi healthcare waste management system is still based on the traditional linear economic model of take–make–consume–dispose. This is considered an obstacle toward achieving sustainability, due to its negative economic, environmental, and social impact [

43]. Transition toward a circular economy by implementing closed loops (reduce, reuse, and recycle) can positively affect the status of the environmental management system, as reported previously [

8].

To enhance the environmental sustainability level of healthcare organizations, the implementation of a healthcare waste policy should involve all levels of staff, including healthcare workers. Furthermore, since the healthcare waste pattern varies among departments, training should be designed according to specific staff and departmental requirements [

44,

45]. The provision of training programs in environmental management is a key factor that should encourage the staff toward a more environmentally friendly attitude and practice. However, relying only on a passive training approach does not always bring about long-term behavioral changes [

46]. Enhancing enablers and eliminating barriers to proper waste management can also help create positive behavioral changes. Alzahrani suggested that the healthcare waste management policy in Saudi Arabia must be based on both a bottom-up and a top-down approach, where staff training and staff empowerment to tackle waste represent the bottom-up solution, while law and regulations aligned with sustainable waste practices represent the top-down solution [

23].

At the individual level, some of the participants did not view sustainability as their social responsibility or waste management as part of their jobs; rather, they suggested that the main factors that affected employee waste management practices were linked to the organizational culture. Therefore, any attempts to introduce recycling and other sustainable practices need to be incorporated into the healthcare waste policy. Transparency, in terms of the publication of sustainability reports, was also identified as a crucial factor affecting social responsibility [

47]. Sharing of information about the economic and environmental benefits of sustainable waste practices would make the employees more likely to become environmentally friendly. Therefore, health workers should be made aware of the financial cost of and carbon emissions contributed by each type of waste. The involvement of healthcare workers in developing and implementing a waste policy would also increase their sense of ownership, which, in turn, would make them more likely to be responsible for the successful implementation of any sustainable measures [

4,

44].

5. Conclusions

This study explored the sustainability of the current Saudi healthcare waste management system from different perspectives. The major critical points were identified based on an examination of the information obtained from document analysis, interviews of key informants, a focus group session, and observations. Despite the heavy financial investment in HMW management, the MSW management system is not well equipped. Consequently, there is an ever-increasing load on the system, resulting in an unsustainable healthcare waste management system. Generally speaking, sustainable healthcare waste management practices can be achieved by integrating an element of social responsibility within the waste policy as well as by enhancing employee awareness, adding a training component, developing programs, and increasing the promotion of the environmental and economic benefits of sustainable practices.

The process of working through data triangulation was considered effective as the combination of primary and secondary sources not only strengthened data reliability and validity but also provided a holistic view to better inform further investigation. However, the study had some limitations, as our observations were based on subjective assessment and, therefore, more evidence was needed. In addition, HMW and MSW estimation was not especially reliable due to the shortage and poor quality of data in some health facilities. However, we believe that our estimations give a rough indication of the total healthcare waste produced and the natural resources consumed. To the best of our knowledge, our extensive document analysis revealed that there is only one study in all the GCC countries that assesses MSW in healthcare facilities [

33]. Therefore, future research is required to estimate HMW and MSW production and components. Overall, despite the limitations, this paper should facilitate the development of a waste policy and some of the actions that healthcare organizations can take toward the creation of a more environmentally sustainable waste management system. These actions might include future plans that enhance documentation, digitization, and effective multisectoral collaboration. The results can be generalized to other developing regions, especially the GCC countries, which are similar not only in their healthcare waste policies and procedures but also in terms of their economic growth, culture, and community.