Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the association between employees’ CSR perceptions and their career satisfaction. Moreover, the mediating roles of organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and psychological capital in the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction are also examined. Finally, the moderating roles of internalized moral identity and symbolic moral identity in the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction are investigated. A cross-industry sample of employees from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was collected. The results show that CSR perceptions positively affect career satisfaction. Organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and psychological capital mediate the link between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction. Both dimensions of moral identity (internalized moral identity and symbolic moral identity) positively moderate the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has witnessed an increasing interest in the last two decades [1]. This is mainly because companies have begun to understand that they can achieve success through engaging in socially responsible activities. CSR activities are found to affect financial performance, market share, stock prices, sustained competitive advantage, and many other organizational level factors (e.g., [2]). Initially, most of research was focused on exploring the macro-level outcomes of CSR such as financial performance. However, interest in the investigation of micro-level outcomes increased in recent years [1]. In order to better understand the micro-level foundation of CSR, employees are considered to be extremely important. This is mainly due to the fact that CSR implementation takes place only when employees are involved in the CSR policies. One of the most important questions that academicians have investigated thoroughly is the effect of CSR activities on employee level attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes [3]. Among various internal and external stakeholders that are influenced through CSR, employees stand out because they can directly observe, participate, criticize, react, and implement CSR programs.

Employees might react differently to the CSR actions, and their perceptions define their consequent attitudes and behaviors [4]. Thus, it is critical for managers to understand how employees react to CSR activities and what effects do these activities create on their outcomes? CSR perceptions influence employee behaviors and attitudes such as organizational commitment, turnover intentions, burnout, organizational citizenship behaviors, job satisfaction, task performance, creativity, work engagement, organizational identification, and voicing behavior (e.g., [1]). Although the relationships between CSR perceptions and general well-being, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction have been investigated, the particular effect of CSR perceptions on employees’ career satisfaction has been seldom researched. There is only one study that has examined the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction [5]. Therefore, this study is going to find out the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction, besides exploring the underlying mechanism through which this effect occurs. This link is worth investigating because how employees react to CSR programs would provide positive meaning to their careers.

CSR is widely described as corporate policies and activities that aim to create positive effect on all stakeholders and are beyond the economic interest of the organization. Companies should develop responsible practices towards the society and the environment so that men and women are able to build their professional careers [6]. It is important for policy makers to understand the factors that contribute to career satisfaction of employees. Career satisfaction refers to the level of satisfaction that one has over the duration of one’s career. There have been very limited studies on the antecedents of career satisfaction [7], as researchers have mostly examined the outcomes of career satisfaction [5]. Investigating antecedents of career satisfaction helps employers to manage those employees who show propensity to move across enterprises, and transition into exit from the industry altogether [8].

Career contexts at the workplace are changing and understanding the antecedents of one’s career satisfaction needs further investigation. This is especially true in today’s context, as feeling good at the workplace is an important factor to ensure positive outcomes. Career satisfaction helps to create a vibrant workforce, allowing employers to retain talent that could be critical in attaining organizational success. This study examines a perception–emotion–attitude–behavior sequence by investigating the socio-emotional micro-foundations of CSR. Drawing from the appraisal theory of emotion, we propose that CSR perceptions significantly affect emotions (i.e., organizational pride), job attitudes (i.e., organizational embeddedness), and psychological resources (i.e., psychological capital) that in turn relate to job-related outcomes (i.e., increased career satisfaction). Moreover, the internalized and symbolic moral identity of employees moderate the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction. The reason to select organizational pride is that it is an emotion in which employees might feel good because of association or belongingness to particular groups [9] that are hedonically preferred by individuals. Consequently, organizations engaging in CSR practices earn good name and are able to build an organizational image that would be viewed positively by employees [10], enhancing the feelings of pride in organizational policies. When an employee perceives that CSR activities of his/her organization are directed towards betterment of social and environmental dynamics, positive cues emerge, and thus organizational pride develops. When employees perceive that organizational CSR is directed towards betterment of society and environment, it creates a very good fit between organizational values and norms and personal values, thus embedding employees in their jobs [11]. In the context of this study, the relevance of organizational embeddedness is especially logical because CSR practices spread positive feelings and these feelings can be felt everywhere in employment relationships due to which employees make stronger attachment with the organization [12].

The third mediator that this study is going to investigate is psychological capital (PsyCap). PsyCap is an individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by: “(1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed in challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success” [13]. When CSR is perceived as favorable, the motivation and cognition associated with it increases PsyCap, which in turn, increases an employee’s pro-social behaviors and work meaningfulness [14], and positive work outcomes [15]. CSR perceptions affect the PsyCap of employees. As Ngo et al. [16] argued, “PsyCap helps employees to translate their psychological resources to subjective and objective career success”. Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that CSR perceptions influence career satisfaction, and that PsyCap mediates this effect. In sum, the perception-emotion-attitude-behavior model that this study unravels the association between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction through organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and PsyCap.

Finally, this study intends to examine the boundary condition of moral identity in the context of CSR-career satisfaction relationship. Moral identity is one’s “self-concept arrayed around a set of moral traits, such as compassion, fairness, generosity, and honesty” [17]. Individuals differ from each other on the basis of their moral identities, and as such their moral behaviors also differ accordingly. There are two dimensions of moral identity. The first dimension is the degree to which moral traits reflect one’s private, ideal, and actual self, referred to as internalized moral identity. The second dimension is the reflection of moral traits as a public or social self, which is known as symbolic moral identity. These two dimensions are compatible with each other. Strong moral identity individual has greater degree of centrality of the moral traits to the self-concept. Perceiving organizational CSR as valuable is likely to amplify the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction because strong moral identity reinforces and validates an employee’s own self-concept in presence of these valuable CSR initiatives. Moral identity has been found as an important boundary condition in explaining the effect of CSR perceptions on employee outcomes such as job satisfaction [18], in-role job performance and helping behavior [19], and organizational citizenship behavior [20]. Extending their findings, it is reasonable to suggest that moral identity strengthens the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction. Moreover, given that career satisfaction is an individual’s plan to develop and improve in the longer term, it is seen as contingent upon self-concept of moral traits. Therefore, the combination of moral identity and CSR perceptions seems to increase an employee’s positivity towards personal development and career advancement i.e., career satisfaction.

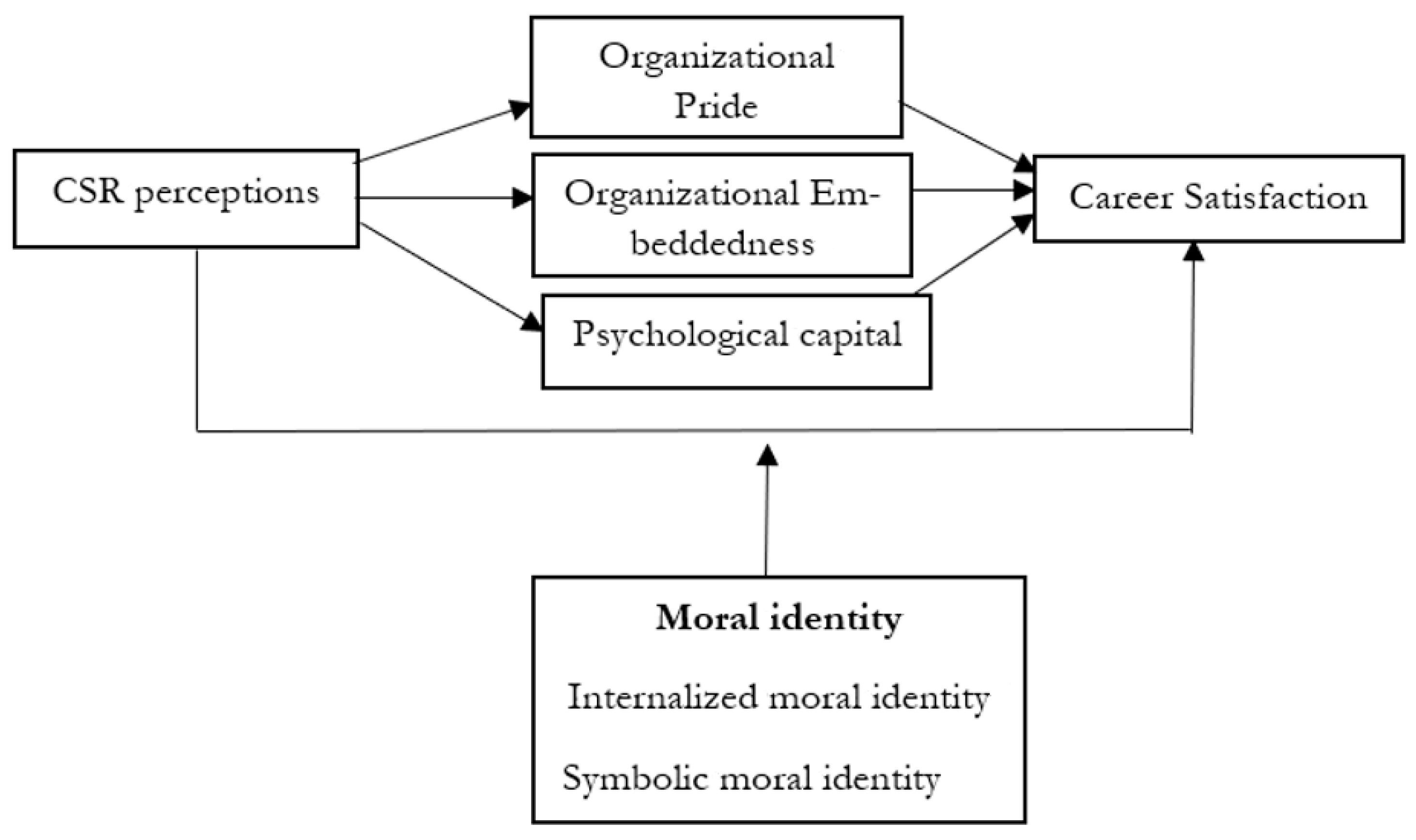

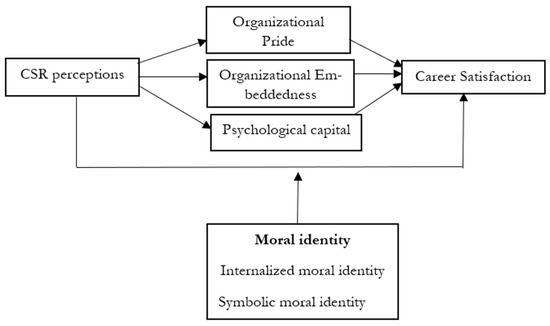

This study intends to contribute to the literature in following ways. First, the link between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction is minimally investigated. This study answers the question: as CSR perceptions affect job-related outcomes [1], how is career satisfaction (satisfaction an individual obtains from the intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of his or her career) influenced by CSR perceptions? Second, there is a lack of understanding of CSR-employee outcomes relationships due to absence of potential mediators and moderators. What is evidently absent in the CSR literature are studies that could explain the underlying mechanism (mediators and moderators) in CSR-employee level attitudes and behaviors relationships [21,22]. Third, a comprehensive model linking perceived CSR with career satisfaction has not been investigated in previous studies. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [5] found CSR perceptions to positively relate with career satisfaction and work engagement was the mediator between them. They suggest that future research could look into other intervening variables in order to better explain the link between CSR and career satisfaction. Oo et al. [10] found that collectivism and person–organization fit moderated the relationship between CSR perception and organizational citizenship behavior. They also called for further research into the effects of CSR perceptions on other employee behaviors and outcomes. This study attends to these calls and investigates how perceived CSR is related to career satisfaction through organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, psychological capital, cultural orientations, and moral identity. Fourth, the micro-level assessment of CSR has received considerably less attention as compared to the macro-level investigation of CSR (e.g., [1]). Employees are one of the most important stakeholders that have often been ignored. CSR perceptions affect employees’ attitudes and behaviors. This study examines how an individual’s perceptions about CSR affects his/her job-related attitude (i.e., career satisfaction). Figure 1 presents the theoretical model of the current study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. CSR Perceptions and Career Satisfaction

The concept of CSR has transformed from profit maximization to taking care of the society and the environment. It initially originated in developed countries but slowly, the importance of CSR has been realized across industries, countries, cultures, and contexts. Nowadays, due to increasing pressure from various regulatory bodies and stakeholders, companies have found CSR as a strategy to gain competitive advantage. CSR activities have been found to affect a variety of stakeholders such as customers [23], current employees [24], prospective employees and local people [25]. While some of the businesses regard such initiatives as a conscientious obligation, in other words, an activity to return what they get from the society, others approach it with economic concerns such as getting through the legal liability of tax payment or as a reflection of the values owned. CSR considers balancing the activities that organizations undertake in terms of profit, planet, and society [21]. It is not only the profit that companies have to strive for but also the societal improvement, environment protection, legal compliance, and stakeholders’ interests. That is, organizations simultaneously look for opportunities to maximize profit and protect the welfare of the society, environment, employees, customers, and other stakeholders. CSR can be evaluated and analyzed more efficaciously by using a pragmatic framework based on the organization’s management and its relationship with internal as well as external stakeholders [26].

Employees are considered one of the most important stakeholder in CSR literature and organizations should take care of their CSR perceptions. CSR has been found to affect the psychological and behavioral outcomes of employees [3]. Employees’ perceptions of CSR refer to cognitive processes and beliefs about the importance of CSR and its effectiveness in terms of environmental responsibility, welfare of the society, and reputation to contribute towards social and environmental progression [27]. CSR perception is based on subjective assessment of CSR rather than objective measurement. The reason to study subjective assessment is that it is a more proximal antecedent of an employee’s attitudes and behaviors [1,20]. Kong et al. [3] found that employees’ subjective perceptions about organizational CSR predict work attitudes and behaviors much better as compared to objective or firm level CSR. They suggest that employees ascribe attributions to the corporation’s CSR actions and it might happen that an organization is genuinely and sincerely trying to uplift the society and environment, but employees think that these practices are not real and that they are in place just to meet the minimum criteria. Similarly, it might be that an organization is engaged in CSR activities symbolically without any real intent to contribute to society and environment but because of their effective advertising and marketing of these activities, an employee might consider CSR as a genuine and substantive effort on organization’s part. As a consequence, it is the perception of the employee that explains better what attitude and behavior he/she would engage in. The importance of employees’ perceived CSR was highlighted in previous studies, which emphasized that employees have the major responsibility to implement CSR because the success of CSR primarily depends on the employees’ attitude and behaviors [22,28]. When organizations initiate CSR programs, they tend to develop intangible resources such as humanistic culture, social responsiveness, attraction, stronger identification, and pride, and these resources help employees to display greater desire to work for such places [29].

When employees perceive CSR programs as real and genuine towards the betterment of society and environment, they become more satisfied with their jobs. Job satisfaction is an employee’s opinion about the level of satisfaction at the current job whereas career satisfaction is broader in nature and it encompasses an individual’s perception about the accumulative effect of experiences at different jobs and his/her progression over a period of time through these jobs. Because perceived CSR is found to relate positively with an individual’s level of job satisfaction, it is reasonable to suggest that CSR perceptions would positively affect an employee’s career satisfaction. Employees find CSR values compatible with their own work meaningfulness and purpose. Hence, working for a socially responsible company for longer term due to pride, identification, compatibility, and humanistic values is likely to retain employees as they feel greater prospects in career pursuit at such places. This is in line with social exchange theory (SET) that suggests that working for a socially responsible company creates high quality relationships between employees and employers and fosters feeling of responding with the norm of reciprocity and in doing so, positive job outcomes are generated [30]. The relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction can also be argued on the basis of social information processing (SIP) theory. CSR practices that make positive sense-making among employees are viewed as investments in the betterment of the workforce, environment, society, customers, and the products. These investments make employees to feel that their organization cares about the economic, social, legal, environmental, philanthropic, and ethical aspects, simultaneously. One of the investments that an employee might consider pivotal is the concern of the organization to personally develop him/her.

Socially responsible activities provide greater opportunities to employees to equip themselves with enhanced set of skills and abilities along with better career prospects [5]. As a result of advancement at personal levels, individuals are better able to accomplish career goals and develop new skills. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [5] suggested that providing career advancement opportunities can be part of CSR and when employees perceive their organizations to provide growth and training opportunities in their CSR programs, they tend to remain in such organizations for longer time, consequently, reducing turnover and increasing the overall career success perceptions. They conducted the study on flight attendants and found that positive perceptions about CSR enhanced career satisfaction of flight attendants. Moreover, they suggested that when employees think that social responsibility is being fulfilled by the organization, the meaningfulness, pride, attachment, and happiness one gets from it translate into positive outcomes such as career satisfaction. Rupp et al. [31] and Zhu et al. [32] reported that employees with a positive attitude toward CSR practices are more likely to have strong job and life satisfaction and they report greater levels of loyalty to the organization and hence the career. They feel that staying in such organizations would satisfy their intrinsic needs and make them proud of the fact that they are part of the organization that takes care of the surroundings (community and environment). Employees responding positively to CSR activities find greater purpose, meaning, and long-term attachment with the job as well as organization. Their jobs become more meaningful and impactful to them. Hence, they see greater prospects in terms of their careers by staying in socially responsible organizations. Based on above arguments, we propose:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a positive relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Organizational Pride

Organizational pride refers to “the pleasure taken in being associated with one’s employer” [33]. It captures “the extent to which individuals experience a sense of pleasure, positive feeling, and self-respect arising from their organizational membership” [34]. To understand how employees perceive and react to CSR actions, the positive emotions associated with organizational pride might be highly logical to study [35]. When an employee witnesses organization’s behavior, the immediate and most direct response is in form of his/her emotions. Amongst various emotions, one of the strongest emotions that an employee feels is the cognizance of cues leading him/her to feel good about the group or organization as well as himself/herself being part of that group or organization that is engaging in a particular behavior [36]. The positive views about oneself and the group help in enhancing self-enhancement and pleasure. These positive views are universal, and everyone prefers them. Employees develop feelings of pride in being associated to organizations engaging in positive cues. When an organization implements CSR programs, it conveys positive cues to its employees, thereby, increasing feeling of organizational pride. Employees then think that their organization is involved in genuinely protecting the natural environment and uplifting the society, and this would help to generate an emotion of pride and prestige [37]. It is a feeling that one develops when positive cues emerge from the group association. If an organization engages in CSR programs that are aimed to uplift the society and the environment, employees will attach themselves more positively with such an organization. For example, a feeling of pride is definite when an employee comes across his/her organization’s impactful role in addressing social and environmental needs through CSR [22]. In the same vein, if an employee is cognizant of his/her company’s CSR actions from external stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, competitors, and/or government regulatory authorities, his/her organizational pride enhances considerably.

Pride among employees develops when they get positive cues and information due to their organizational membership. They feel that their social status and self-enhancement could rise as a result of group membership. There are reasons to believe that CSR perceptions enhance career satisfaction through mediation of organizational pride. First, in the context of CSR perceptions and employee outcomes, pride is highly relevant because it regularly induces cognitive appraisals, leading to affirmative evaluation processes of positivity by associating with the organization and its CSR activities. By witnessing CSR that is aimed at making the planet a better place to live and contributing its own due share in these efforts, employees think, evaluate, and interpret CSR programs and relate them to their own work-related outcomes. Employees assess stakeholders’ demands to engage in CSR and organization’s response by displaying greater pool of resources in order to address these demands. As a result, positive evaluations and feelings of pride emerge that in turn increase person–environment fit [38]. Second, pride increases when individuals evaluate CSR and think that what is being done by their organization in order to contribute toward social and environmental betterment is far ahead of what its competitors and other organizations are doing. These social and environmental initiatives endorse employees’ cognitive evaluations that the organization has resources and capabilities to take care of stakeholders’ interests [38]. Thus, employees might consider organizational resourcefulness and concern for stakeholders to their own advantage by showing greater satisfaction in careers.

Third, the ideological needs of employees nowadays are getting stronger [39]; so, working in a socially responsible company satisfies their needs of contributing positively in the environmental and social issues, developing pride among them [15]. These ideological needs when satisfied create a working environment with strong values compatibility that can consequently make employees feel career success. Fourth, there are some other symbolic cues that CSR perceptions evoke [22]. Through CSR programs, an organization is seen as praiseworthy by employees in symbolic values such as morality, ethicality, kindness, selflessness, caring, kindness, and responsibility [40]. These emotional reactions in the form of organizational pride might help employees to find greater meaning and purpose of life, leading to an enhanced career satisfaction. Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Organizational pride mediates the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Organizational Embeddedness

Organizational embeddedness is the level of attachment that one has with his/her organization due to strong bonding inside as well as outside the organization [41,42]. Organizational embeddedness comprises of three main components: (1) links with the community; (2) links with the job and workplace; and (3) links with the organization in case one has to leave it [43]. It is a long term investment in an organization, and employees’ level of attachment to the organization determines organizational embeddedness [41]. It is a strong binding force that keeps employees away from leaving the organization and is attributed to various reasons, an individual feels immersed in the organization and local community. This bond develops a long-term attitude that is reflective of the positive feelings that one has about his/her organization. When an employee feels organizational embeddedness that has arisen as a result of the organization’s CSR practices, he/she experiences other positive feelings that makes quitting the current organization tougher for him/her [11]. The level of association and bond with the organization, job, community, and other people increases due to CSR perceptions. Employees feel that serving the current organization is making their jobs more meaningful and purposeful, and the fit between what they value and what the organization values is greater. Moreover, the level of sacrifice needed to leave such an organization that engages in CSR activities is also substantively high; therefore, an employee might decide to stay in the current organization due to better career prospects in long term [44]. In turn, organizational embeddedness positively affects career satisfaction [45,46]. Therefore, we believe that organizational embeddedness mediates the link between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction. When an employee feels strong association that has arisen as a result of the organization’s CSR practices, he/she experiences other positive feelings that makes quitting the current organization tougher for him/her [11]. Employees feel that serving the current organization is making their jobs more meaningful and purposeful, and the fit between what they value and what organization values is greater.

When CSR is perceived as positive, it creates greater match between individual values and organization’s norms and values. Organizational CSR programs are designed to involve community and other stakeholders. CSR brings people together so that they can work on common cause and interact with each other. These closely-knit communities evoke social learning and develop strong relationships among those who work on common interests. Such relationships develop friendship ties inside as well as outside the organization. Employees feel greater embeddedness because close ties with community and other stakeholders developed over time are stronger due to CSR implementation. Moreover, positive sense-making about CSR helps employees to establish social relationships with customers, community, and other stakeholders. They are less willing to sacrifice the respect and trust earned through these social relationships [11]. Organizational embeddedness help employees to acquire skills, knowledge, abilities, competencies, and capacities through regular communication, cooperation, exchange of knowledge, and leadership [15]. As such, an employee finds more opportunities for advancement, personal development, and effective job performance [11], leading to enhanced career satisfaction. Organizational embeddedness imposes intrinsic and extrinsic pressures to stay as long as they can in the organization [44]. Thus, we can hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Organizational embeddedness mediates the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction.

2.4. The Mediating Role of PsyCap

PsyCap is the combination of states rather than traits developed through positive psychological resources. It is based on motivational propensities and positive emotions [13]. It is reasonable to believe that CSR practices affect PsyCap of employees. When employees perceive that their organizations provide them support to develop their skills and abilities, they become confident to perform tasks [47]. CSR activities enhance an employee’s mastery experiences and through vicarious learning, individuals experience success when organizations behave responsibly in economic as well as social terms. Employees believe that they will get the necessary resources needed for their personal and professional development in an economically responsible environment. As a consequence, self-efficacy of employees increases.

If an organization implements CSR programs, it is expected that ethical practices would be followed. Having an environment where social responsibility, environmental protection, ethical decision making, philanthropic services, and economic viability are considered important, success experiences become readily available, and employees being internal observers of CSR, experience these successes and become resilient [48]. PsyCap also increases when organizations behave within legal, environmental, social, and ethical boundaries [49]. For instance, socially responsible organization adopts actions that are directed toward psychological and physical safety, employee assistance programs, work-family balance, mental health, wellness programs, and occupational advancement. These actions decrease the level of stress and employees are better able to make rationale and logical decisions, especially in urgent and/or crises situations [50]. Resilience is also developed when organizations support career growth through skill enhancement, competence building, and training opportunities. Moreover, economically successful organizations provide attractive salaries that might make them more resilient. Legal and reputational losses of companies that engage in CSR actions are less likely. Therefore, employees perceiving positively the CSR are better equipped to face problems, crises, obstacles, and barriers, and they respond to these setbacks with rationality and resilience, both at individual level as well as at organizational level.

The role of organizational policies greatly determines the psychological resources that employees possess. Shen and Benson [51] suggest that organizations safeguard stakeholders’ interests by engaging actively in CSR programs. Among stakeholders, employees are always considered as a top priority, and that is why they are provided with every possible support so that they can cope with challenges and difficulties arising during the course of work in the organizations. Therefore, CSR creates a deeper sense of purpose and significance, and even during tough times, individuals do not lose hope and remain optimistic by continuing to help others [52]. Psychological guidance that is derived from having positive perceptions about corporate environments, increases employee optimism [47]. Moreover, when CSR activities are perceived as positive, self-efficacy of individuals is maintained and they feel confident to cope with problems and setbacks. Perceived CSR influences work-related outcomes of employees and this influence can be better explained through individual-level psychological mechanisms and still this gap needs to be addressed for better understanding [21,28]. This study suggests that positive psychological resources (PsyCap) are individual level psychological factors that would mediate CSR perceptions and career satisfaction link.

Employees who view CSR actions as means to their self-development and professional growth are committed and dedicated to their work. They are highly engaged and committed to their work. They understand that their organizations would provide all available resources to improve their skills and abilities, advance their careers, achieve personal and career goals, and develop as a professional [5]. When people are high in PsyCap, they possess greater psychological resources having hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience. In such cases, when they find organizational policies as favorable, they tend to work with greater zeal and enthusiasm. They also feel pride in working for such organizations and remain committed to the organization [53]. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [5] found that work engagement mediated the link between CSR and career satisfaction. CSR perceptions create positivity and level of work engagement characterized by vigor, dedication, absorption, and confidence increases, that in turn leads to career satisfaction. Luthans et al. [13] found that PsyCap mediates the effect of organizational climate on employee performance. Ngo et al. [16] found that gender role orientation affected subjective career success through PsyCap.

Individuals with positive sense-making of CSR develop higher PsyCap. Employees who work for a socially responsible organization believe that the organization will value the contributions of staff no matter what economic and other pressures mount on it. Hence, they feel psychologically safer to mobilize their positive psychological resources in pursuit of work goals. Socially responsible organizations create a supportive and trusting work environment that develops higher willpower among employees to allocate more energy and efforts in performing well [13], and find meaningfulness through their work. PsyCap helps employees to pursue meaningfulness through accumulation of hope, optimisms, self-efficacy, and resilience. When organizations are perceived to act in a socially responsible manner, taking care of social, environmental, and ethical aspects, employees desire more to sustain the positivity for themselves and the organization, and in turn, look to work in such careers for long term. PsyCap includes positive emotions that would translate into fulfilling the needs of personal growth, upward development, autonomy, purposeful life, competence, positive relations, and relatedness, which in turn enhances one’s subjective well-being, career commitment, job satisfaction [54], and career satisfaction. Based on these arguments, the current study proposes:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

PsyCap mediates the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Moral Identity

Previous studies show that individual differences such as personality [55], emotional intelligence [56], cognitive style [57], and moral identity [19] moderate the relationship between CSR perceptions and employees’ work-related outcomes. In a study by Wang et al. [19], moral identity is a boundary condition that affects the effect of perceived CSR on organizational identification. They suggest that since moral identity is related to how one thinks about morality, it interacts with one’s perceptions about organizational initiatives and policies to explain the effect on the emotions, attitudes, and behaviors. Extending their argument, this study proposes that CSR perceptions-career satisfaction relationship is going to be moderated by moral identity. Moral identity is organized around a set of moral values and traits [58], and it is a self-conception that provides personal intrinsic motivation. Moral identity varies from person to person, and those with strong moral identity feel that moral traits (e.g., compassionate, helpful, caring, fair, honest, generous, and considerate) are central for defining their self-concept. Moral identity plays an important motivating role in how individuals behave and act. High moral identity centrality helps individuals to activate their moral self-schema or mental representations and moral identity-based knowledge so that their behaviors could be managed whereas low moral identity people do not internalize moral values and moral schemas. Such people usually do not care much about what morality and ethics are and they do not associate their self-concepts with moral principles [19].

People with high moral identity have moral schemas that are “chronically available, readily primed, and easily activated for information processing” [59]. Internalized moral identity is the extent to which one considers himself to be moral and the degree to which a set of moral traits is central to one’s self-concept [17]. It is rooted in the very core of one’s being. Symbolic moral identity is the extent to which reactions to moral issues are expressed publicly through an individual’s actions. It is the public persona and perception of one’s moral identity. It is the degree to which the person is being true to oneself in public action. Both dimensions of moral identity can be linked with how self-awareness has been theorized in the literature. Self-awareness is a combination of an external, social, and public awareness and an internal and introspective awareness of one’s feelings and inner thoughts. Moral identity focuses on processing of moral information. Employees who have high moral identity process and relate moral information embodied in CSR actions with their own moral values.

The moderating effect of moral identity in the relationship between organizational initiatives and employee outcomes has been examined in previous studies. For example, Rupp et al. [20] found that when employees have high moral identity, the relationship between CSR perceptions and organizational citizenship behavior strengthens whereas low moral identity weakens this relationship. Ormiston and Wong [60] indicated that symbolic moral identity negatively moderated the effect of CSR and ethical behaviors. Wang et al. [19] found that high moral identity strengthened the association between CSR perceptions and organizational identification. Moreover, Singhapakdi et al. [18] suggested that the effect of CSR perceptions on job satisfaction strengthened for employees who were high in moral identity symbolization. They were of the view that people consider CSR practices as a way to self-regulate their moral schemas. Moral reasoning is important in guiding individuals to engage in various behaviors, but it is not sufficient, and integrating organizational policies into moral self-concepts is likely to predict behaviors. The felt obligation towards moral commitment that is based on public-self integrates CSR policies. Thus, they consider CSR programs as morally-relevant behaviors, such as greening the environment, donations, charity, philanthropic activities, eliminating social issues, taking legal and ethical perspectives into consideration, and enhancing firm environmental performance. In sum, moral identity emerges as a key moderating factor between CSR perceptions and employee outcomes. Individual traits act as boundary conditions on the effect of CSR perceptions on employee outcomes [20]. CSR is about a firm’s ethical stance, and individual traits do affect employees’ perceptions and reactions to CSR initiatives. Particularly, morality-related traits such as moral identity are more relevant in CSR-employee outcomes [19].

People have a network of self-schemas, and decision-making and resulting behaviors take place when the particular moral identity becomes salient in a given situation. Moral identity comprises of multiple attributes and depending on situational cues, a subset of these attributes evokes and becomes salient [19]. The nature of CSR is value and moral driven. Hence, the effect of positive sense-making of CSR on career satisfaction is likely to increase when people have greater internalized and symbolic moral identity. A high-level of moral identity helps individuals to fulfill their needs for meaningfulness, purposefulness, and sense of being [61]. Singhapakdi et al. [18] found that perceived CSR and job satisfaction link is moderated by both dimensions of moral identity. Moreover, Wagner et al. [62] also found similar results. They suggested that more importance is given to CSR by employees who have high moral identity. Moral concerns are more salient for employees with relatively high internalized moral identity [63]. They tend to be more involved in volunteering, charity, philanthropy, and moral reasoning [58]. Thus, they would be more supportive of CSR activities [32,64]. They are usually very generous and believe in donating and doing something good for others, and they consider CSR as a way to gain satisfaction through frequent volunteering and donations.

Moral reasoning is more salient for employees with relatively high internalized moral identity. Their emotions of affection, loyalty, trust, and admiration towards the organization are intense. As such, the influence of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction is likely to be amplified for those employees with relatively high than low internalized moral identity [17]. Internalized moral identity helps individuals to view volunteering and pro-social behaviors as part of their self-concept. They tend to feel having more positive psychological resources as a result of the moral values the organization is pursuing through its CSR programs and the self-schemas that one has. Internalized moral identity builds generosity towards others and minimizes social distance towards others, amplifying the positive impact of CSR perceptions on work outcomes such as career satisfaction. Therefore, it is expected that high internalized moral identity would strengthen the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction. Employees high on symbolic moral identity view CSR as a way to reinforce their social or public self. The congruity between organizational CSR values and individual values increases when employees have high moral identity [62]. Symbolic moral identity is also expected to moderate CSR-career satisfaction relationship because the public self is likely to be in harmony with the private self in majority of the cases [19]. More specifically, most of employees are normal in mental health and they integrate their private and public self. It means that those who are high in internalized moral identity are likely to be high in symbolic moral identity [18]. Based on these arguments, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Moral identity moderates the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction such that the effect is greater for high than for low internalized moral identity (H5a) and symbolic moral identity (H5b).

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

Data were collected through a survey of employees from various industries in Saudi Arabia. Those employees were selected who had been implementing different CSR activities, that had an understanding of CSR practices implemented within their organization, and had been working for five years or more in the industry. The researchers targeted around 350 organizations from various sectors. The sectors included oil and gas, agriculture, mining, construction, transportation, healthcare, and hospitality industry were our participants. Fifty organizations from each of these seven sectors were approached. Telephone calls were made to the managers of these organizations and they were briefed about the purpose of the study. Due to COVID19 pandemic, we contacted them through online platforms. Out of 350, managers of 208 organizations agreed to participate in the survey and provided us with the contact information (e-mail ids and phone numbers) of their employees. Then, we contacted a total of 1200 employees through different online mediums. They were provided a link to the online survey. A total of 279 questionnaires were returned. We kept on sending reminders to the participants and aimed at additional participants through LinkedIn and other online social networks (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp, etc.). All of the participants were made cognizant of the purpose of the study. They were notified that they were permitted to ask questions, raise concerns about the study, or leave the survey at any point. Agreement to participate in the survey was part of the questionnaire sent to the participants. Since the survey was conducted online, the signatures of the participants were not acquired. Responses to the survey were anonymous, and all participants were advised that their responses would be confidential. It took around 25 min to fill out the questionnaire that was made available in both English and Arabic. We received 104 additional responses making it a total of 383 valid responses. Given the relatively low response rate, we checked the potential for nonresponse bias by using wave analysis with comparisons between early responders (first two weeks, n = 123), middle responders (third and fourth week, n = 156) and late responders (last two weeks, n = 104). Armstrong and Overton [65] argued that late respondents are representative of non-respondents. The results of t tests for gender, age, education, and industry type, nationality, job position, and tenure of the respondents, as well as the composite scores of the constructs revealed no significant differences between late, middle, and early respondents.

The sample consisted of 259 (67.6%) males and the largest age category was the 31–40 years age group (50.1%). A total of 172 (44.9%) had bachelor degrees, 124 (32.4%) had master degrees, and 12 respondents had PhDs. A total of 197 (51.4%) of the employees were from public limited companies, and 284 (74.2%) were non-Saudis. The respondents were from various industries, and this increased the heterogeneity of the sample. In terms of type of industry, 45 (11.7%) were from oil and gas, 47 (12.3%) from agriculture, 59 (15.4%) representing mining, 39 (10.2%) from hospitality, 64 (16.7%) from construction, 69 (18%) from transportation, and 60 (15.7%) were from healthcare industry. A total of 38.1% of the respondents had a total experience of 10 to 15 years, and 126 (32.9%) of the respondents were holding middle level managerial position (see Table 1 for the sample demographic characteristics).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.2. Measurement of the Constructs

The questionnaire requested employees to rate their opinion about organizational pride, PsyCap, career satisfaction, organizational embeddedness, moral identity (internalized and symbolic), and organization’s CSR programs. All items were measured on 5-point Likert-type scale, with the response set ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To measure employees’ perceptions of CSR, this study adapted 17-item scale of Turker [66]. Organizational pride is measured with four items taken from the study of Cable and Turban [67]. To measure moral identity, a ten item scale developed by Aquino and Reed [17] was used. Five items were used to measure internalized moral identity and five items for symbolic moral identity. A six-item scale developed by Ng and Feldman [12] was used to measure organizational embeddedness. For career satisfaction, a five item scale of Greenhaus et al. [68] was used. Finally, PsyCap was measured by 12 items developed by Lorenz et al. [69]. The survey was translated into Arabic as well. As Brislin [70] specified, the survey was translated into Arabic through reverse translation by a research worker fluent in both languages.

3.3. Data Analysis

The current study employed the covariance based structural equation modeling for testing the developed model. The structural equation modeling consists of two models. These are the measurement model and the structural model. The analyses were made with the AMOS package software. In order to perform the analysis and test the hypotheses, the missing values, extreme values, and distribution of data have to be determined. Through an imputation method and mean substitution technique [71,72], the missing cases are highlighted and in this study, no missing values were identified. To check extreme values, the Mahalonobis D2 value was used, and the current study found no extreme values. To determine whether the distribution was normal, the kurtosis and skewness values were reviewed. Because the kurtosis and skewness values were 2.629 (less than 3) and −1.285 (less than 2), the data set can be said to have a normal distribution.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

In the measurement model, the construct validity and reliability were tested. Table 2 shows the result of confirmatory factor analysis on the theorized seven-factor model (CSR perceptions, organizational pride, PsyCap, internalized and symbolic moral identity, organizational embeddedness, and career satisfaction).

Table 2.

Results of measurement model.

The analysis showed that the study model had an excellent fit (χ2 = 1045.638; df = 693; χ2/df = 1.763; GFI = 0.927; NFI = 0.958; CFI = 0.972; RMSEA = 0.051). Average variance extracted (AVE) value of each latent variable must be higher than 0.50 for the convergence validity [73]. As seen in Table 2, all constructs have higher AVE values than 0.50, thus convergent validity fulfilled. For the discriminant validity, the criterion of Fornell and Larcker [74] was considered. Discriminant validity was achieved since the square root of each construct’s AVE have a greater value than the correlations with other latent constructs. The composite construct reliability was taken into consideration for the reliability of the scales used. The reliability values of the scales used range between 0.784–0.927. Thus, it can be said that reliability is fulfilled [74].

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 provides the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the study variables. As expected, CSR perceptions were found to be positively correlated with career satisfaction (r = 0.581, p < 0.001), organizational pride (r = 0.518, p < 0.01), organizational embeddedness (r = 0.387, p < 0.01), and PsyCap (r = 0.434, p < 0.01). Furthermore, organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and PsyCap were found to be positively correlated with career satisfaction (r = 0.596, p < 0.01; r = 0.621, p < 0.001; r = 0.487, p < 0.01, respectively).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

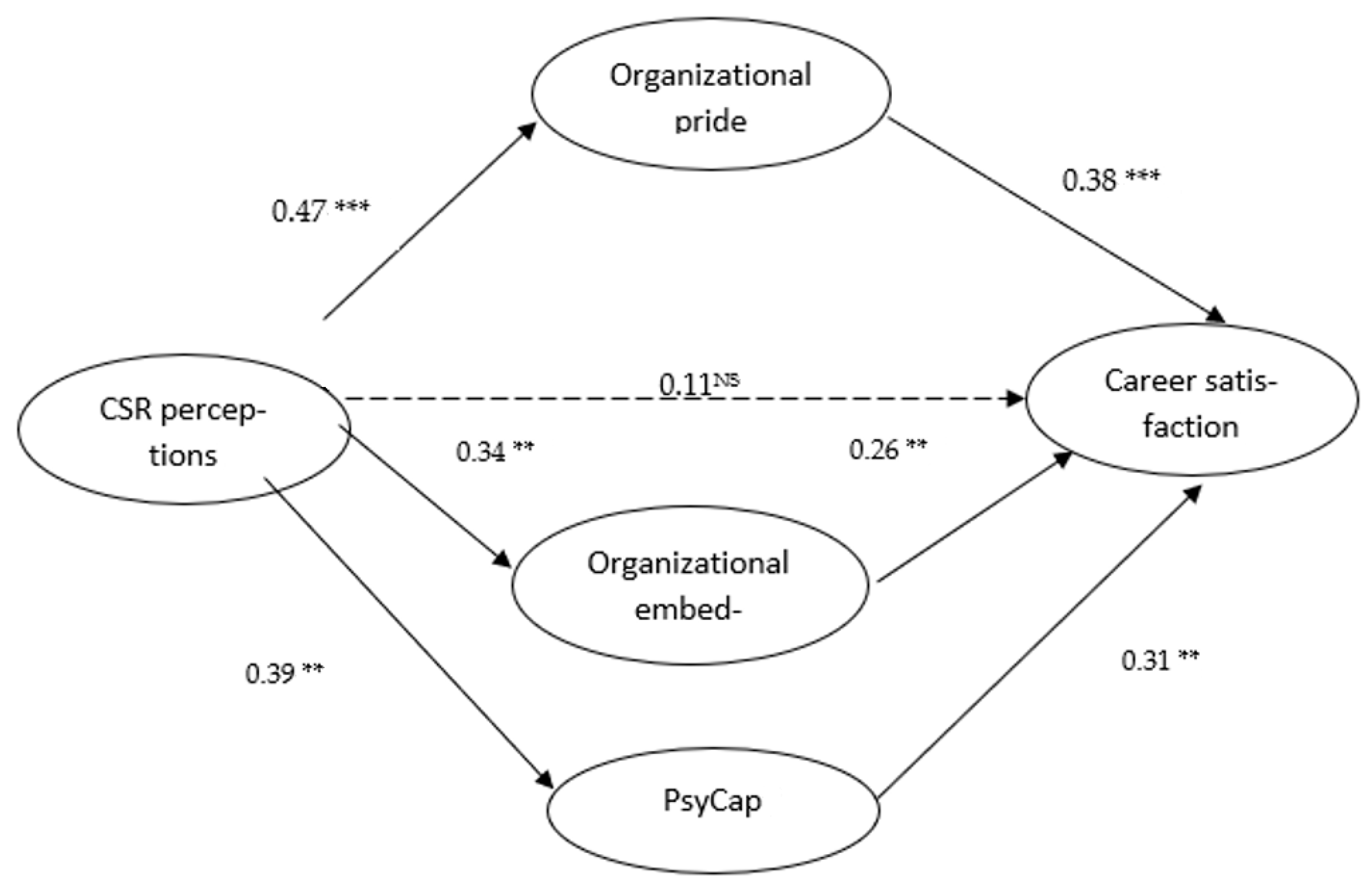

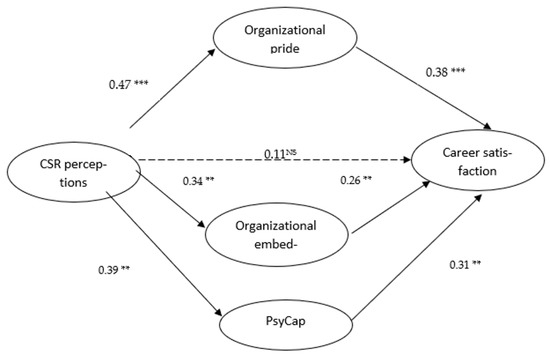

The hypotheses of this study were analyzed using structural equation modeling. All the path coefficients were significant. Employees’ CSR perceptions positively affected career satisfaction (β = 0.563, t = 17.978 p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis 1. Moreover, CSR perceptions were found to positively affect organizational pride (β = 0.464, t = 12.381, p < 0.05), organizational embeddedness (β = 0.386, t = 9.584, p < 0.001), and PsyCap (β = 0.511, t = 14.835, p < 0.001). Career satisfaction positively affected by organizational pride (β = 0.358, t = 8.583, p < 0.05), organizational embeddedness (β = 0.317, t = 7.755, p < 0.05), and PsyCap (β = 0.234, t = 6.926, p < 0.01). Figure 2 showed the path coefficients and hypotheses 3, 4, and 5 were tested. The path values from CSR perceptions to organizational pride (β = 0.47; p < 0.001), from CSR perceptions to organizational embeddedness (β = 0.34; p < 0.01), from CSR perceptions to PsyCap (β = 0.39; p < 0.01), from organizational pride to career satisfaction (β = 0.38; p < 0.001), from organizational embeddedness to career satisfaction (β = 0.26; p < 0.01), and from PsyCap to career satisfaction (β = 0.31; p < 0.01) are significant. Moreover, the path value between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction (β = 0.11; p > 0.05) was not significant, supporting Hypotheses 2–4.

Figure 2.

SEM results for mediation. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; NS is not significant.

Furthermore, the indirect effects for mediation were calculated through a bootstrapping test at a 99% confidence interval with 10,000 samples [75]. To get confidence intervals in indirect effects, the bias-corrected bootstrapping method is applied. If the lower and upper bound does not include zero, the null hypothesis can be rejected. For bootstrap analysis, a minimum 5000 resamples to be used as recommended by Preacher and Hayes [75]. Table 4 shows the bootstrapping results. As can be seen, there are significant indirect effects of organizational pride on the CSR perceptions-career satisfaction relationship (estimate = 0.21; z = 4.52 and p < 0.001), and of organizational embeddedness on the CSR perceptions-career satisfaction relationship (estimate = 0.17; z = 3.85; p < 0.01), and finally of PsyCap on the CSR perceptions-career satisfaction relationship (estimate = 0.14; z = 3.21; p < 0.01). Consequently, the H2, H3, and H4 hypotheses were supported.

Table 4.

Bootstrapping results for indirect effects.

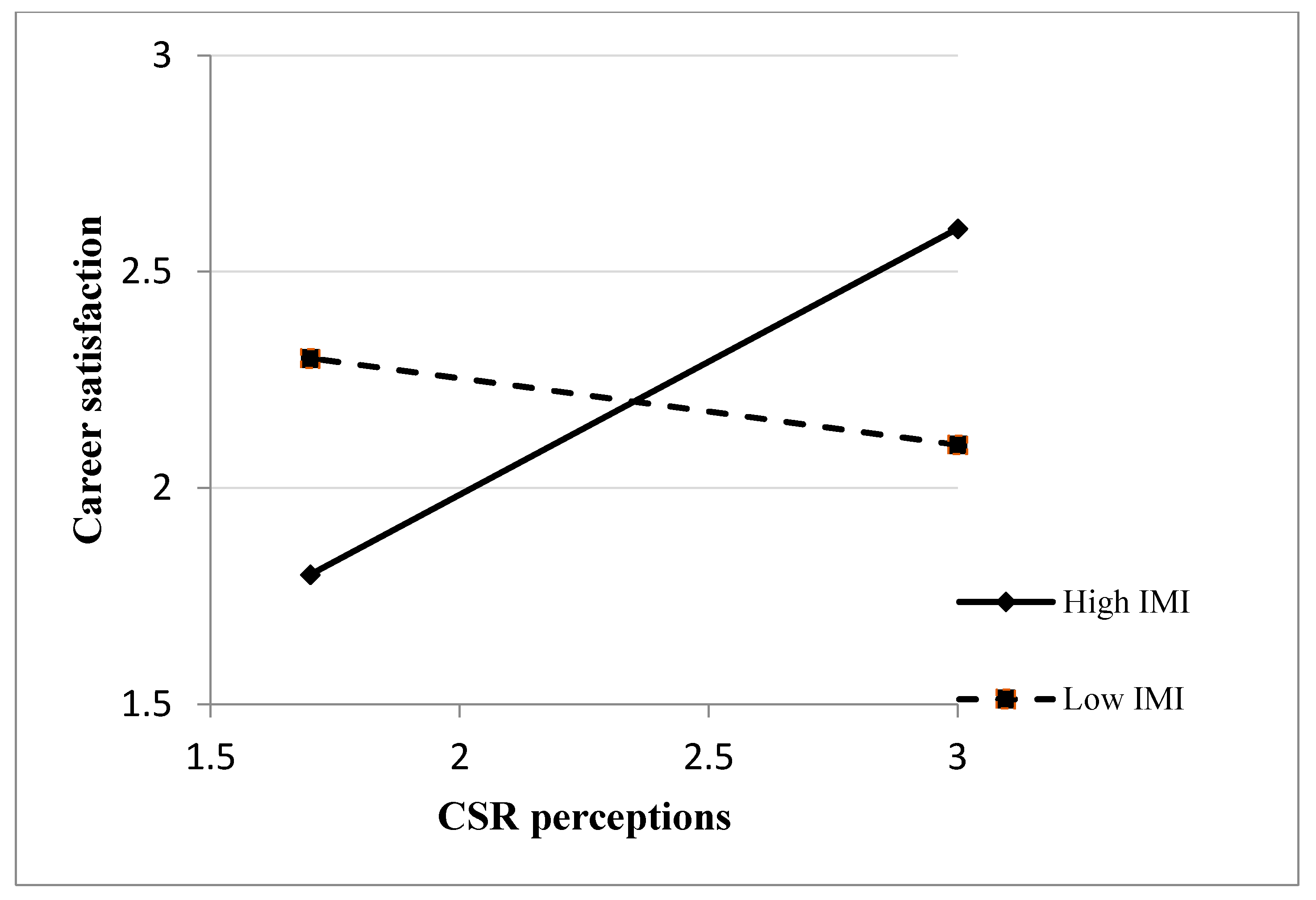

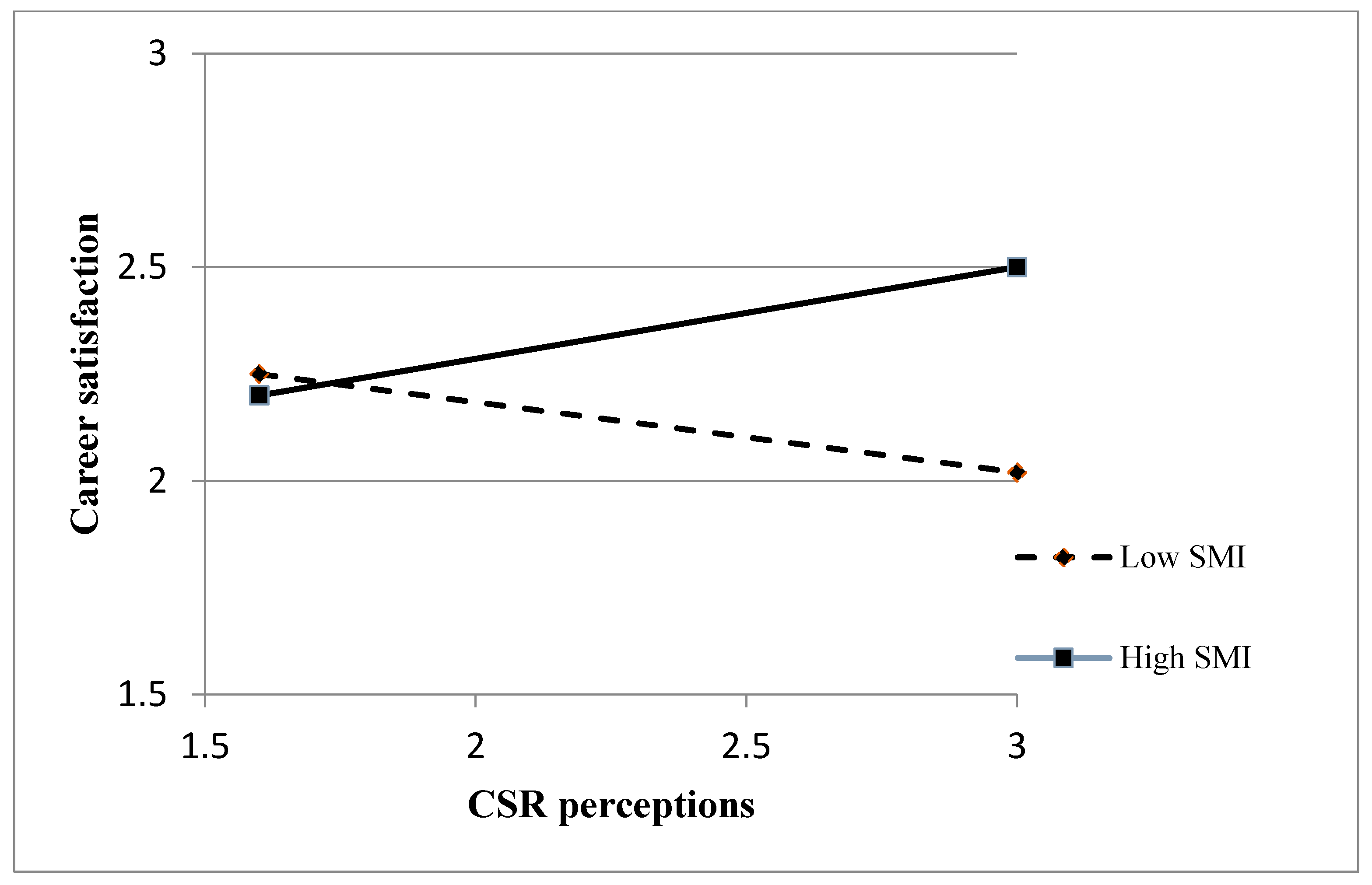

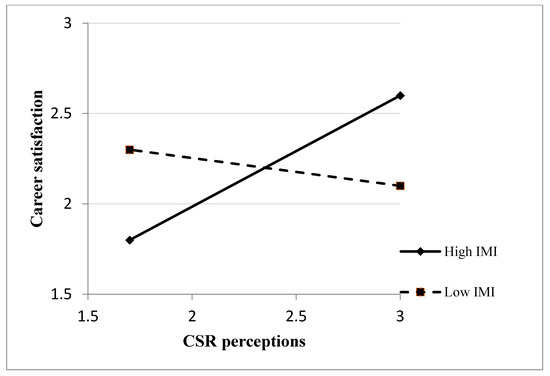

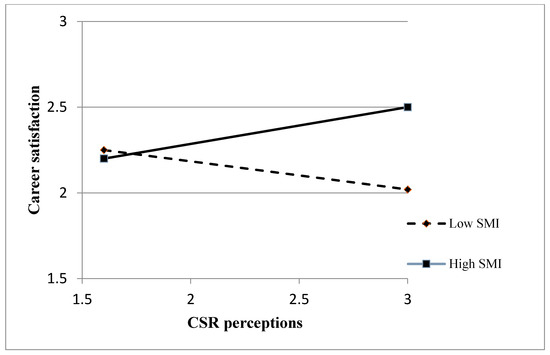

The moderation effects of internalized and symbolic moral identity were tested with hierarchical regression analysis. As can be seen from Table 5, the interaction term between CSR perceptions and internalized moral identity was significant (β = 0.19, p < 0.001). To further explore this interaction, we plotted the results using Aiken and West’s (1991) procedure of ±1 SD for different levels of internalized moral identity. As seen from Figure 3, the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction was strengthened when internalized moral identity was high rather than when it was low. The simple slope tests demonstrated that the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction is significant only when internalized moral identity is high (simple slope = 0.24, t = 2.78, p < 0.001), but not significant when internalized moral identity is low (simple slope = −0.14, t = −0.91, ns), supporting Hypothesis 5a. The interaction term between CSR perceptions and symbolic moral identity was significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.01). As shown in Figure 4, we plotted the results and found out that the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction was strengthened when the symbolic moral identity was high. The simple slope tests showed that the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction is significant only when symbolic moral identity is high (simple slope = 0.18, t = 2.11, p < 0.05), but not significant when symbolic moral identity is low (simple slope = −0.13, t = −1.28, ns). Thus, Hypotheses 5b was supported (See Figure 4).

Table 5.

Moderation results.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of internalized moral identity (IMI).

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of symbolic moral identity (SMI).

5. Discussion

This study examined a comprehensive model linking CSR perceptions with career satisfaction through mediation of organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and psychological capital. Moreover, the moderating roles of internalized and symbolic moral identity on the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction were also tested. We found that when employees positively perceive CSR, they seemed to be more satisfied with their careers. When employees perceive their organization to be socially responsible, they tend to display greater career satisfaction. In agreement with SET [30] and SIP [5], working for a socially responsible company creates high quality relationships between employees and employers that in turn fosters feeling of responding with the norm of reciprocity and in doing so, positive work outcome such as career satisfaction increases. CSR practices that make positive sense-making among employees are viewed as investments in the betterment of the workforce, environment, society, customers, and the products. These investments make employees to feel that their organization cares about the economic, social, legal, environmental, philanthropic, and ethical aspects. As a result, the prospects to work for such an organization are enhanced and employees feel satisfaction in the long term. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [5] found that employees of socially responsible airline companies made positive sense-making of CSR programs and hence they were more satisfied with their careers. We also found that organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and psychological capital mediated the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction. These findings are in line with previous studies that focused on exploring the underlying mechanisms in the relationship between CSR perceptions and employee positive work outcomes [1,5,76]. In the context of CSR perceptions and employee outcomes, pride is highly relevant because it regularly induces cognitive appraisals [35], leading to affirmative evaluation processes of positivity by associating with the organization and its CSR activities.

When CSR is perceived as positive, it creates greater match between individual values and organization’s norms and values [11]. CSR brings people together so that they can work on common cause and interact with each other. These closely-knit communities evoke social learning and develop strong relationships among those who work on common interests. Such relationships develop friendship ties inside as well as outside the organization. Employees feel greater embeddedness because close ties with community and other stakeholders developed over time are stronger due to CSR implementation. Moreover, positive sense-making about CSR helps employees to establish social relationships with customers, community, and other stakeholders. They are less willing to sacrifice the respect and trust earned through these social relationships. Individuals with positive sense-making of CSR develop higher PsyCap. Socially responsible organizations create a supportive and trusting work environment that develops higher willpower among employees to allocate more energy and efforts in performing well [13], and find meaningfulness through their work. PsyCap helps employees to pursue meaningfulness through accumulation of hope, optimisms, self-efficacy, and resilience. When organizations are perceived to act in a socially responsible manner, taking care of social, environmental, and ethical aspects, employees desire more to sustain the positivity for themselves and the organization, and in turn, look to work in such careers for long term. Finally, we found that both internalized moral identity and symbolic moral identity moderated the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction such that the effects were stronger when employees had high rather than low moral identities. This finding is line with previous results that showed positive moderating role of moral identity on the mediated effect of organizational identification in relationships between perceived CSR and employee turnover intentions, in-role performance, and helping behavior [19]. These findings indicate that enhancing positive sense-making about CSR actions may energize those with high internalized moral identity and symbolic moral identity to feel a relatively higher career satisfaction.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study advances theory in the following ways. First, the majority of studies focus on objective assessment of CSR rather than considering employees’ perceptions and subjective assessment. This is surprising because employees being internal stakeholders are important for CSR implementation and if they are not aware of CSR programs, the effect of CSR on their attitudes, emotions, and behaviors might not occur [22,77]. In order to implement CSR, organizations rely heavily on employees because they are the ones who are directly involved in CSR implementation. Based on what they think about CSR, their attitudes and behaviors are influenced. This study extends CSR literature by examining how employees’ perceptions of CSR affect their emotions, attitudes, and behaviors. Second, although few studies have explored the mediating roles of employee attitudes in CSR-work outcomes links [19,52,78], the role of employee emotions that are central in micro-level assessment of CSR [22] has largely been ignored. We extend prior studies on perception–emotion–attitude–behavior framework, and suggest that organizational pride (a positive emotion) mediates the effect of CSR perceptions on career satisfaction. Pride develops when organization engages in some extraordinary actions [33], and CSR perceptions help employees to feel pride by considering the organization to be more moral, caring, honest, ethical, responsible, competent, and considerate.

Third, CSR influences job attitudes, and organizational embeddedness is one the strongest job attitudes bonding individuals to their organizations through stable psychological forces [22]. This study extends embeddedness theory by showing that organizational embeddedness is another plausible reason due to which CSR perceptions might affect favorable behavioral outcomes (increased career satisfaction). Organizational embeddedness frames employees’ perceptions of their organizations in functional ways [22] and they get purpose, meaning, and direction to their jobs due to enhanced embeddedness [79,80]. Thus, organizational embeddedness is likely to explain why CSR perceptions result in positive work outcomes such as career satisfaction. Fourth, although previous studies have investigated a number of individual and organizational level mediators, the way in which psychological resources and positive organizational behavior could mediate the effect of CSR perceptions on employee work outcomes has been minimally examined. Mao et al. [47] suggest that when CSR is perceived in positive sense, the psychological safety, hope, self-efficacy, and resilience increase significantly among employees. PsyCap helps to promote positive feelings that consequently make employees loyal, committed, and satisfied with their overall lives [81]. Such a positive mental state by employees helps them to display subjective well-being, job satisfaction, and career success [47].

Fifth, this study is the first of its kind that links CSR perceptions with career satisfaction. In order to retain talented pool of employees, organizations need to ensure that employees are satisfied with their careers. Verbruggen and van Emmerik [82] report that the majority of employees look for changes in their career, and this has severe consequences on their engagement and performance outcomes. The literature shows that there are various factors that affect employees’ career satisfaction such as supervisory support [83], organizational employability culture [84], leadership styles [85], perceived organizational career management [86], corporate ethical values, and organizational learning culture [87]. Kong et al. [3] suggested that employee’s perceptions about the organizational ethical and social responsibilities might influence career satisfaction. However, there has been no study on the effect of employee’s perceived CSR on his/her career satisfaction. Although the effect of CSR perceptions on job satisfaction and work-life satisfaction [87] was investigated, how CSR perceptions might influence an employee’s career satisfaction still remain to be answered. This study answered the question by finding out that CSR perceptions increase career satisfaction.

Sixth, by focusing on CSR perceptions as a potential antecedent of career satisfaction, this study adds to the career management literature and addresses the call to further investigate the determinants of career satisfaction by Jung and Takeuchi [88], and Ngo and Hui [89]. Career satisfaction is considered important by practitioners since it ensures retention of employees. When employees are satisfied from their careers, they tend to stay longer in organizations and remain committed and loyal. Managers actively look for ways to improve career satisfaction because it provides retention of talented pool. Finally, Singhapakdi et al. [18] suggested that moral identity of an employee might serve as a boundary condition and future research should look into the effect of CSR perceptions on employee outcomes. This study extends the moral identity literature by explaining the moderating role of internalized and symbolic moral identity on CSR perceptions-career satisfaction link.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This study has some extremely useful implications for managers. When organizations design CSR initiatives, they seldom consider the impact that these initiatives can have on the overall career satisfaction and retention of their employees. This study shows that CSR perceptions enhance career satisfaction. Managers should regularly communicate CSR activities with employees to keep them informed about CSR. To monitor CSR effectiveness, managers should find out whether CSR activities develop feelings of pride among employees and whether employees feel stronger embeddedness as a result of the CSR. Moreover, CSR can enhance PsyCap of employees by engaging in activities that provide maximum resources to employees so that they feel confident, hopeful, resilient, and optimistic. The commitment of organization to implement CSR embeds employees into the organization. The reaction to CSR varies among individuals, and one possible factor in this regard is moral identity. By communicating CSR policies, employees would be sensitized to understand the importance of CSR, morality, ethicality, and honesty and associate these values with their own. Likewise, by promoting activities that focus on frequent interaction with outside community and external stakeholders, and by encouraging participation of employees in designing and implementing CSR programs, greater career satisfaction could be achieved.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

As with any study, ours has potential limitations. First, self-report data is a potential limitation because it might inflate relationships among variables. Second, the cross-sectional nature of data limits our understanding of CSR perceptions that might keep on changing with time. Future studies should collect data about CSR perceptions at multiple points in time. Third, the present study used age, gender, education, and experience as control variables to ensure the validity of the results. However, some other factors such as industry type, job position, and job nature may limit the validity of the research results. Therefore, future research can use such factors as control variables to further validate our findings. Fourth, data were collected from Saudi Arabia that may limit the generalizability of the findings across other countries. Future studies should replicate these relationships in other countries since the moral identity and CSR activities might vary from country to country. The roles of cultural orientations such as individualism/collectivism and power distance orientation might also prove helpful in understanding the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction. Fifth, future studies should consider moderating role of moral identity on other relationships because moral identity may influence the effects of CSR perceptions on organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and PsyCap. Finally, although cross-industry sample provides statistical robustness and generality; future research could investigate whether these results apply to specific industries, allowing greater control over the contextual environment.

6. Conclusions

Although CSR at the micro-level has been investigated quite extensively in developed countries, limited studies are found in the Asian context, especially in the gulf region. The Saudi government has adopted several efforts to transfer the country to the sustainable economic growth and development, since they have developed the 2020 National Transformation Program (NTP) and The Saudi Vision 2030. These two strategic programs were designed to set far-reaching objectives and goals to transform the country into one that is sustainable, diverse and at the center of international trade. By investigating how employees react to CSR efforts and how these reactions affect their work outcomes across different cultures, industries, and continents, we would be able to develop a generalized understanding of CSR-outcomes relationships. To predict career satisfaction, research has mostly focused on examining the effect of job-related traits. However, limited studies are found in literature that investigate the influence of employee’s perceptions about organization’s values and actions on their career satisfaction. Moreover, underlying mechanisms explaining the link between perceptions and career satisfaction also lack in current literature. This study found that CSR perceptions positively affect career satisfaction and organizational pride, organizational embeddedness, and psychological capital mediate the link between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction. Moreover, internalized moral identity and symbolic moral identity positively moderate the relationship between CSR perceptions and career satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Each author of this article contributed as follows: data collection and analysis were completed by B.M.A.-G.; M.S.S. was responsible for the results, conceptualization and methodology; B.M.A.-G. and M.S.S. contributed equally to the writing, reviewing, and editing. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received internal funding by King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals with grant #SR201002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the support received from King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals under University Funded Grant #SR201002.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Donia, M.B.L.; Ronen, S.; Tetrault Sirsly, C.-A.; Bonaccio, S. CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Corporate social responsibility perceptions and employee engagement: Role of psychological meaningfulness, safety and availability. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Sehleanu, M.; Li, Z.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Badulescu, D. CSR as a potential motivator to shape employees’ view towards nature for a sustainable workplace environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, F.; Abbas, Z.; Muhammadi; Hussain, I.; Saleem, M.; Hussain, A.; Aman, J. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ negative behaviors under abusive supervision: A multilevel insight. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Karatepe, O.M. An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassermann, M.; Fujishiro, K.; Hoppe, A. The effect of perceived overqualification on job satisfaction and career satisfaction among immigrants: Does host national identity matter? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2017, 61, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harhara, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Hussain, M. Correlates of employee turnover intentions in oil and gas industry in the UAE. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthier, M.H.J.; Rhein, M. Organizational pride and its positive effects on employee behavior. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Gurunathan, L. Linking perceived corporate social responsibility and intention to quit: The mediating role of job embeddedness. Vision 2014, 18, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. The effects of organizational and community embeddedness on work-to-family and family-to-work conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1233–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—Employee performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2017, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Corporate social responsibility, multi-faceted job-products, and employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.Y.; Foley, S.; Ji, M.S.; Loi, R. Linking gender role orientation to subjective career success:The mediating role of psychological capital. J. Career Assess. 2014, 22, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Reed Ii, A. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Lee, D.-J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Roh, H.; Senasu, K.; Yu, G.B. Effects of perceived organizational CSR value and employee moral identity on job satisfaction: A study of business organizations in Thailand. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 8, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Moore, J.H.; Wang, Z. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and moral identity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Yam, K.C.; Aguinis, H. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 72, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-Y.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-H. Customer perceptions of airline social responsibility and its effect on loyalty. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2012, 20, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, H. The influence of corporate social responsibility on travel company employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmotaleb, M.; Mohamed Metwally, A.B.E.; Saha, S.K. Exploring the impact of being perceived as a socially responsible organization on employee creativity. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.-M.; Kang, S. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and job performance: A sequential mediation model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Abdullah, M.I.; Alvi, A.T. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility impact on employee outcomes: Mediating role of organizational justice for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived csr affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Lai, K.-H. How is employee perception of organizational efforts in corporate social responsibility related to their satisfaction and loyalty towards developing harmonious society in chinese enterprises? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S. A Matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Br. J. Manag. 2013, 24, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Achar, C.; Han, D.; Agrawal, N.; Duhachek, A.; Maheswaran, D. The psychology of appraisal: Specific emotions and decision-making. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Griffin, J.J.; Predmore, S.C.; Gaines, B. The cognitive–affective crossfire: When self-consistency confronts self-enhancement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Merrill, C.B.; Hansen, J.M. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsachouridi, I.; Nikandrou, I. Organizational virtuousness and spontaneity: A social identity view. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 1302–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, J.; Kärreman, D. Conscience as control-managing employees through CSR. Organization 2013, 20, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.D.; Bennett, R.J.; Jex, S.M.; Burnfield, J.L. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]