Abstract

Chronic care management is dependent on productive interactions between patients and healthcare professionals. Digital health technologies (eHealth) open up new possibilities for improving the quality of care, but there is a limited understanding of what productive interactions entail. This study explores characteristics of productive interactions to support self-care and healthcare in the context of eHealth use in diabetes care. We collected qualitative data based on interviews with nurses and responses to open-ended survey questions from patients, prior to and post using an eHealth service for self-monitoring and digital communication. We found that eHealth’s influence on productive interactions was characterized by unconstrained access, health parameter surveillance, and data-driven feedback, with implications for self-care and healthcare. Our findings indicate that eHealth perforates the boundaries that define interactions under traditional, non-digital care. This was manifested in expressions of uncertainty and in blurred boundaries between self-care and healthcare. We conclude that the attainment of a sustainable eHealth ecosystem will require healthcare to acknowledge eHealth as a disruptive change that may require re-organization to optimally support the productive use of eHealth services for both patients and staff, which includes agreement on new routines, as well as social interaction rules.

1. Introduction

Chronic care management requires collaboration and integration of resources from several actors, including patients, healthcare professionals, and the community. This has been emphasized in the Chronic Care Model (CCM), which was first presented in the late 1990s [1,2] and remains one of the defining models for the management and organization of chronic care. The model outlines how outcomes are achieved by productive interactions between patients and healthcare professionals, which in turn depend on effective self-management support, delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information systems [2]. More recently published models include the House of Care [3], and the model of healthcare coproduction [4]. All these models exemplify an effort to conceptualize how people, technology, and resources can be integrated to co-create sustainable value in networked healthcare [5]. Productive interactions between patients and professionals form the core of chronic care management, viewed from a service-dominant mindset [6]. Yet, over twenty years after the introduction of the CCM, the transformation of a healthcare system that is mainly designed for ambulatory care to effectively manage chronic care still remains “a formidable challenge” [7].

eHealth is increasingly recognized as a means to support individuals in their self-care and to facilitate interaction and collaboration with healthcare, thereby maximizing the value created by the CCM. In this study, we define eHealth as “health services and information delivered or enhanced through the internet and related technologies” [8]. eHealth services can be viewed as bridge elements that create connections between actors in an ecosystem [9]. The eHealth enhanced Chronic Care Model (eCCM) outlines how eHealth may augment the components of the CCM, for example, by promoting access and control over personal health records, enabling self-tracking of health data, empowering involvement in shared decision making, supporting preparation for appointments, and enabling personalized decision support through visualization of data and reminders [10]. The eCCM also includes an eHealth education component to improve health literacy, which was not part of the original CCM model. Thus, there are various technologies that have been suggested to improve the functionality of the different components of the CCM.

However, to unleash the potential of the eCCM, productive interactions between patients and providers must be supported, for example, by enabling complete feedback loops between the patient and the provider, which implies a regular process of transmission and interpretation of patients’ health data, addressing individual needs, and providing timely feedback [10,11]. eHealth services such as personal health records and mobile devices for self-tracking and telecommunication are examples of technologies that can facilitate complete feedback loops, at least when these services are used under the umbrella of a trusting, cooperative, and collaborative partnership [10]. For example, in diabetes care, where frequent interactions and collaboration among patients and healthcare professionals are critical to address clinical issues and lifestyle change, studies have shown that eHealth-supported message exchange between patients and healthcare professionals may be a viable strategy to motivate patients’ blood glucose monitoring and thereby support their self-care [12,13,14]. It should be considered that an eHealth service may not only influence interactions in already existing partnerships but may also contribute to changes in the partnerships themselves [15]. For example, eHealth may induce task shifting among healthcare staff, as well as between healthcare staff and patients, which may, in turn, have implications on how productive interactions are realized. Thus, productive interactions facilitated through eHealth services require organizational adjustments, which may involve the development of new services and viable financial models to support them [15].

There is still limited research on how eHealth interventions enable complete feedback loops between patients and healthcare, in conjunction with elements of the CCM [10]. A review of eHealth tools that enable text-based communication between patients and healthcare professionals in chronic care found that while studies evaluated the clinical effectiveness of eHealth tools, there were very few studies investigating the mechanisms that affected productive interactions [16]. The majority of eHealth tools targeted diabetes care and were mainly used for symptom reporting and to support lifestyle and behavior change [16]. Previous research showed promising results of eHealth interventions in terms of their effects on clinical outcomes and diabetes self-management [17]. Integrated, patient-centered care based on the CCM has been identified as very cost-effective for diabetes patients [18], but the conformity of mobile eHealth applications to the components of the CCM is generally weak [19]. Interventions appear to be most effective when an interactive format is used, such as text messaging [20]. Yet, many eHealth applications have just focused on some essential functionalities to monitor health parameters, such as tracking of blood pressure, blood glucose, weight, and activity [19,21]. There has been little focus on how both patients and providers can use patient-generated data together [22], and features enabling productive interactions between patients and staff are often lacking [23]. A review concluded that the clinical effects were greater when patients using a mobile eHealth service were supported by healthcare professionals, but also that there is a need for studies that explore digital health technology interventions more holistically, e.g., how productive interactions may be enabled to promote improved self-care and healthcare [24]. As these studies illustrate, our understanding of the mechanisms by which eHealth may influence productive interactions in chronic care remains inconclusive. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore characteristics of productive interactions to support self-care and healthcare in the context of eHealth use in diabetes care. In this, we add to the limited understanding of how sustainable value creation in chronic care management can be enabled by taking a micro-level perspective, exploring the productive interactions from the perspective of both patients and professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in a Swedish primary care setting with diabetes nurses and diabetes patients who participated in an eHealth intervention pilot for self-monitoring and digital communication at two primary care centers (PCCs). The eHealth service consisted of a mobile application with the following core features: health data monitoring (e.g., glucose, weight) through manual input or by data transfer from external monitoring devices (e.g., glucose monitoring device); self-rated health data (e.g., quality of sleep, physical activity, diet, tobacco use, medication) through regular questionnaires; and secure communication to connect with healthcare staff through chat and video. Self-monitored and self-rated health data were automatically shared with diabetes nurses who accessed the data through a web portal. In case of potentially serious deviations from reference limits, alerts were communicated to both patients and diabetes nurses.

2.1. Recruitment

Five diabetes nurses from the two PCCs participated in the pilot and recruited participants for the pilot among their diabetes patients. Being diagnosed with diabetes Type 2 or prediabetes, being over 18 years of age, having a smartphone and an email account, and being able and willing to communicate in Swedish were criteria for inclusion. Eligible patients who were interested were informed about the pilot and received instructions on how to download and get started with the eHealth service. They also filled in a consent form to be contacted by researchers for participation in a baseline and a follow-up survey. The eHealth service provider assisted the nurses in setting up individual accounts and care plans for recruited patients.

Shortly after pilot initiation, in February 2020, the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in the region of Stockholm, where the study was conducted [25]. The pilot continued despite the pandemic, but recruitment was slow. We made the assessment that it would be of value to complete the data collection and analysis, even though the recruitment was limited.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Participating nurses signed a written informed consent form and patients consented electronically. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm (reg nr. 2018/625-31 and 2019-05792).

2.3. Collection of Qualitative Survey Data Capturing Patients’ Expectations and Experiences

This study uses qualitative data from two open-ended questions in a baseline survey (T1) that was distributed to patients upon recruitment and eight open-ended questions in a follow-up survey (T2) that was distributed approximately 6 months into the pilot (see Table 1). The surveys were distributed electronically together with detailed information about the study. The data in this study are based on the free text responses of fourteen patients, of which five responded to both the baseline and follow-up surveys, seven responded only to the baseline survey, and two responded only to the follow-up survey. The respondents’ ages ranged from 56 to 70 years; six (43%) were female. At baseline, six (43%) of the respondents had known about their diabetes for one year or less, four (29%) had between one and ten years of experience, and four (29%) had more than ten years of experience. All but two reported that they had visited their primary care center during the past 6 months; the median was 3 (IQR 3–4) times. All reported that they used information technologies (e.g., computer, tablet, or smart phone) on a regular basis, most of them (12/14, 86%) several times per day.

Table 1.

Open-ended survey questions from the baseline survey (T1) and follow-up survey (T2).

2.4. Collection of Interview Data Capturing Diabetes Nurses’ Expectations and Experiences

To facilitate an in-depth understanding of the diabetes nurses’ expectations and experiences of using the eHealth service and how it influenced productive interactions, interviews were conducted prior to the pilot and six months into the pilot. Two semi-structured interview guides were developed by the authors. The first guide included questions regarding the diabetes nurses’ understanding of their role in relation to their patients, their care, and their self-care, during and between consultations. The respondents were asked to describe the ways in which they communicated with their patients, what a physical meeting entailed, and their expectations and concerns about using the eHealth service. The second interview guide focused on their experiences of using the eHealth service, whether it had changed anything in their patient consultations, and in what way they understood their relations to their patients. All diabetes nurses involved in the pilot study at the two PCCs were invited via email to participate in the interviews. At PCC 1, one nurse participated in the pilot; at PCC 2, four nurses participated. All accepted to be interviewed.

The interviews were conducted by three of the authors, with two interviewers participating in each interview. All co-authors have a PhD, two are MDs, and the other three are full time researchers; all are trained in qualitative research methodology. The researchers and respondents had no personal or professional relations with each other outside of the project.

The first interviews were all conducted at the PCCs, audio recorded, and transcribed. The transcripts were read by two of the authors (CW and TS) directly after the transcript was available so the interview guide could be gradually improved. The interviews lasted around 45–60 min. Before the follow-up interviews, all initial interviews were re-read to facilitate follow-up questions regarding the expectations the respondents had expressed before the pilot started. Hence, the interview guides for the follow-up interviews were adjusted to each of the initial interviews. At the time of follow-up, two nurses at PCC 2 had been given other assignments and were no longer part of the pilot and were hence excluded. The follow-up interviews with the other three nurses were conducted via a video conferencing system, due to COVID-19. The interviews lasted around 35–45 min, and they were recorded and transcribed.

2.5. Analysis

The questionnaire and interview data were analyzed in several steps using an inductive thematic approach [26]. First, the questionnaire data, consisting of 71 individual answers (1238 words), were imported to a mind-mapping software [27] where they were categorized inductively, guided by the research question. All four co-authors collaborated in this process. After agreement had been reached on the categorization of data and labeling of themes and subthemes, two of the authors (TS and KPH) read through all the interviews. Thereafter, the interviews were coded by using the preliminary themes developed in the analysis of the questionnaire data as a coding scheme. TS and KPH coded half of the interviews individually and discussed and compared their findings. The remainder was coded by TS alone. The analysis of interview data resulted in minor adjustments of the themes and subthemes which were presented to the other co-authors and thoroughly discussed until consensus was reached.

3. Results

The qualitative analysis resulted in three main themes, capturing diabetes patients’ and diabetes nurses’ expected and experienced influence of eHealth on productive interactions, self-care, and healthcare. The subsequent description of themes is supported by illustrative quotes that have been translated from Swedish to English.

3.1. Theme 1—eHealth’s Influence on Productive Interactions

eHealth’s influence on productive interactions was characterized by unconstrained access, health parameter surveillance, and data-driven feedback.

3.1.1. Unconstrained Access

For some of the participants, the notion of unconstrained access was the main driver for engaging in the eHealth pilot. The digital communication channel allowed asynchronous communication. This meant that patients were not constrained by phone hours, which made it easier to get in touch with healthcare. One nurse mentioned that some of her patients worked night shifts and were very keen on the opportunity to be able to ask questions 24/7, aware that no immediate response could be expected. Similarly, nurses described how the new communication channel also made it easier for them to get in touch with patients. They communicated either exclusively through the chat, or by using the chat to schedule a telephone visit at a convenient time, as it was often difficult to get hold of patients when calling unannounced.

[What do you look forward to about using the eHealth service?] To not be constrained by lousy and unavailable phone hours.(Patient 2, baseline)

The patients liked it. Most of all, they liked the chat. They were able to send messages to me, back and forth, without having to wait in a call queue. They had a direct contact. This was something they appreciated.(Nurse 4, follow-up)

Nurses suggested that in the past, care communication had generally been limited to the physical meeting, whereas now, the interaction could go on after the meeting with follow-up questions through the chat. This type of asynchronous communication had both its benefits and challenges. Prior to the introduction of the eHealth service, a nurse described that she was looking forward to being able to communicate in writing as phone lines could sometimes be weak and one could easily forget what was said. In a chat, there is always the opportunity to scroll back. However, it was later noted that for some patients, the written communication became an obstacle due to language barriers. The intended purpose of the messaging service in the eHealth service had not been specified and message content was not limited by design. As one patient described, the messaging service was used to raise “other questions” as well, without specifying what type of other questions. Another patient acknowledged that he/she was unsure if the nurse really had time to engage. Nurses confirmed that unlimited access had its drawbacks as it led to increased stress and workload. One described how she did not want to log into the eHealth system as she knew there would be messages waiting for her that she would not have time to deal with.

If I don’t get the time for it, if I have not had time to log in, then of course it’s a burden, both […] stress, work environment and then it’s much worse for one’s psychological wellbeing. That I should feel guilt for not having the time to log in and do what I should do.(Nurse 5, follow-up)

3.1.2. Health Parameter Surveillance

For patients, the eHealth service provided an easy and convenient way to transfer health data to their nurses, without having to wait until the next meeting. Health parameter surveillance was something nurses described as part of their role also before using the eHealth service, but with access only to the data patients brought to their annual meetings. Sometimes, patients brought their notes in their native language, which could be difficult for the nurse to understand. Enabled by the technology, nurses would be able to monitor and review the patients’ health parameters on a more regular basis, which was considered a great advantage. A nurse described that prior to the introduction of the eHealth service, she needed to call the patients that she wanted to monitor more closely. She hoped that the eHealth service would make her work easier as it would allow her to just look for deviations on the screen, rather than having to call her patients.

The greatest benefit is that you discover the patients’ poor measurements in time, that you can provide direct feedback. It does not need to wait until I have scheduled a physical visit with the patient. I can provide the feedback straight away, and hopefully, get a prompt response from the patient, why things look the way they do.(Nurse 5, follow-up)

Prior to the eHealth pilot, one patient expressed concern that health data may be misused to cause harm. Such concerns were also raised to nurses directly. Indeed, nurses described that the increased access to continuous data led to nurses getting insight into patients’ lives that they did not otherwise have. For some patients, the nurses’ ability to surveil their health parameters was experienced as something positive. It also caused nurses to become more engaged in their patients’ health. For example, one nurse reported noting a serious change in a patients’ blood glucose and found out that the patient was hospitalized. Another nurse closely followed her patient’s health parameters through a cold. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the cold symptoms evoked more attention and concern than usual.

My diabetes nurse had the opportunity to track my measurements more often [and] was overall satisfied with my reporting.(Patient 3, follow-up)

One of them was over 70 and got a cold. And then we could track his blood sugar pretty well, and keep in contact over the chat, how he was doing, […] I experienced that it made him feel safer. But I also thought it was relieving to have some oversight [due to the COVID-19 pandemic] […] It felt good because I didn’t even need to call him in the morning, I could just log in and check that his blood sugar was okay.(Nurse 4, follow-up)

3.1.3. Data-Driven Feedback

Similar to health parameter surveillance, data-driven feedback circles around the topic of health data monitoring. In contrast to surveillance that is performed by healthcare staff without requiring interactivity, data-driven feedback highlights patients’ expectations of getting feedback from healthcare, as a response to shared health data. Prior to using the eHealth service, a nurse expressed that she looked forward to getting access to health data that she could respond to. Some had already engaged in data-driven conversations with patients who used other technologies to share self-monitored data with healthcare staff between scheduled consultations. With the new service, patients expected both more frequent and timely communication with healthcare staff. After having used the service, both nurses and patients reported that patients got more feedback on their health data, resulting in a more frequent follow-up of their health status. As one nurse expressed, this type of bi-directional dialogue was of particular value during dose adjustments, which could be managed more efficiently.

It is great to have when, for some patients when doing dose adjustments and initiating therapy, to have a closer contact. And instead of calling, where there might be a lot of chitchatting, this takes much less time if you have many patients and quickly want to make adjustments for several of them. Then you save time. And that it is secure.(Nurse 4, follow-up)

Nurses described that their relationship to patients could vary, and that some needed encouragement, while others did not. One of the nurses emphasized that it was necessary to establish a trustful relationship before finding her role. Further, some suggested that prior to the introduction of the eHealth service, they could only support patients during physical visits but had no role in the patients’ care between their annual meetings. Hence, a nurse described how she tried to empower patients to increase their engagement in managing their diabetes:

So when we meet it is very important for me to say that ‘You need to own your illness, you need to take responsibility, you need to simply look after yourself. I can only inform you at these visits, then you have to take charge’.(Nurse 1, baseline)

After having used the eHealth service, nurses described how they contacted patients through the chat and commented on the patients’ health parameters, for example, if their blood glucose levels had changed or were low or high. While the eHealth service now enabled nurses to take an active role between patient visits, this role was different when the patient was not someone the nurse had an established relationship with. The eHealth service enabled nurses to interact with all patients at the primary care center, not just their “own” patients. One nurse described how she would not feel comfortable advising on more challenging issues when the patients were not her own.

I’ve logged in and simply, when I’ve seen too low blood sugar levels or too high blood sugar levels, I’ve chatted with the patients. And then I’ve fed back to the responsible nurse. […] If the patient, if there are more challenging things, then I may say that ‘I will talk to your responsible nurse and then she can contact you.’(Nurse 5, follow-up)

3.2. Theme 2—eHealth’s Influence on Self-Care

eHealth’s influence on self-care was characterized by support for health parameter monitoring, increased self-care knowledge, support for adequate and timely decisions and actions, and support for tailoring to individual needs.

3.2.1. Supports Health Parameter Monitoring

Patients expected that regular health parameter monitoring would provide them with a better picture over their health and make it easier for them to gain better control over their blood glucose and lifestyle (e.g., nutrition and physical activity). Similarly, a nurse expected that the visualization of health data would positively influence patients’ self-care: “When you see it in print it’s completely different” (Nurse 3, baseline). Nurses expected that patients would become more engaged in their self-care by using an eHealth service.

Then you work in a completely different way perhaps, with both treatment and life habits. You’ll have to think. And maybe more—if you add weight and diet, then you can see what you do that affects your blood sugar.(Nurse 1, baseline)

After having used the eHealth service, patients reported gaining better control over their blood glucose in particular. It was described that some patients paid a lot of attention to their measurements, almost too much. While nurses experienced that other digital health technologies had sometimes, in the past, been a problem to patients, the eHealth service was considered easier to use and also required less language skills. Nevertheless, some patients had expected better support, such as better instructions and reminders that were more aligned with their daily routines.

3.2.2. Increases Self-Care Knowledge

Before using the app, no patients described any expectations regarding increased self-care knowledge. However, nurses reported having used health data to help patients to understand the connections between their blood glucose levels, diet, and physical activity. After having used the eHealth service, one patient reported learning about “the meaning of diet, physical activity, illness and other factors influencing my glucose levels” (Patient 4, follow-up). Others, however, reported that they did not learn anything new that they did not know already before. One nurse also reflected that she had hoped the eHealth service would make patients reflect more upon their own blood glucose levels, but that she had seen no such examples.

3.2.3. Supports Adequate and Timely Decisions and Actions

Patients expected that the eHealth service would inform their decisions by guiding them to do the right thing to improve their health. After having used the service, one patient noted that it could have been helpful, but was not. However, some did experience that the eHealth service reminded them to monitor their health and engage in healthy behaviors. It was also noted that visualization of data helped both patients and nurses to see patterns in health data that made it easier to explore connections between behavior (e.g., diet) and health, but also other factors (e.g., illness) that could temporarily affect their blood glucose levels.

Apart from the importance of diet and exercise I have also seen clear effects on my glucose levels when I am ill or suffering from other strains.(Patient 4, follow-up)

I liked the feature that you could see blood sugar as a diagram. That is, for me that is very clear—that I can see it graphically, so that I can see if there is a raise after a meal. Are levels rising at night? Is it the fasting glucose that rises? When do the problems occur? When do hypoglycemias occur? Because then I can help them to adjust.(Nurse 4, follow-up)

Nurses described that prior to using the eHealth service, it was difficult to support healthy habits as the contact with the patients was so rare. One nurse expected that when the patients would start to self-monitor their health, their awareness would increase, and, unconsciously, they would start taking better care of themselves. While some patients reported that they could recognize certain patterns, this did not necessarily result in changed behaviors. A nurse described how one of her patients consistently reported low numbers but did not attempt any adjustments to improve them.

There is one [patient] who is always low, but she does not change much in her treatment, she continues to be on a low level.(Nurse 3, follow-up)

3.2.4. Supports Tailoring to Individual Needs

Patients reported some frustration over the usability of the eHealth service (e.g., inconsistent terminology, typeface, overall poor user interface). Further, it was noted that the service did not make it possible for patients to adjust the timing of reminders to their individual needs and daily routines. This had to be done by nurses, who also had to make some changes to the general settings for issuing recommendations and warnings as these did not suit all patients.

I noticed straight away that it sends a warning signal below five, and then I quickly realized that if you are on Metformin pills then this warning that you are low and advice to eat something sweet is not necessary. So then you have to log in to the patient’s account and remove this, so I will probably have to log in to all patient accounts and check that everything is really is in line with their medication.(Nurse 4, baseline)

Nurses described how some patients stopped using the system due to language barriers. For example, a patient spoke Swedish but did not feel confident in her written Swedish and hence dropped out of the study. There was some agreement that the eHealth service mainly suited less experienced patients and also patients who had difficulty visiting the primary care center on ordinary opening hours.

I think it will be easier to see who is managing their diabetes well without needing to come in for a visit. And especially for those who work night shifts and so on, many of them have wanted to participate because they find it difficult to come here at daytime.(Nurse 4, baseline)

3.3. Theme 3—eHealth’s Influence on Healthcare

eHealth’s influence on healthcare was characterized by more informed physical meetings, and optimized care at the individual and population levels.

3.3.1. Informs Physical Meetings

Some patients feared that the introduction of the eHealth service would result in fewer physical meetings. Due to COVID-19, the physical meetings were limited during the study period, so this could not be followed up. However, nurses did not suggest that any ordinary meetings with a patient had been cancelled due to the use of the eHealth service, but rather that the eHealth service helped to identify when additional physical meetings were necessary. Most of the patients who had visited the primary care center after starting to use the service reported that they had discussed their self-monitored health parameters during the meeting with their diabetes nurse. This was confirmed by nurses, who experienced that the self-monitored health data were a reliable source of information that informed the physical meetings and saved time.

Yes, that we discuss the information in the app, that will probably be a very natural thing to do. […] And I think the patients will want to talk about that. […] We will have material to discuss, it becomes very concrete.(Nurse 2, baseline)

3.3.2. Optimizes Individual Care

None of the patients expected that using the eHealth service would lead to changes in their care or drug regimen. However, nurses described how they aspired to use the system for individualizing care plans and goals for patients, and how it would be advantageous to be able to see how much the patients exercise and to follow their diets. They also believed that the continuous health data monitoring may help them to detect things that they would otherwise miss, which would enable them to provide better care. In the follow-up survey, one patient reported that their use of the service had led to a change in drug dosing, while others reported no changes in their treatment. One of the nurses described how she could help a patient to adjust insulin doses based on the surveillance data and chats. This was experienced to also lead to more preventive care because the close monitoring of patients’ health parameters allowed for adjustments at an earlier stage, preventing potential complications.

There was one patient that I asked to lower his dose. He was low, at 3.5 one morning. And I think that could have become a critical situation. Even if it did not, I think it was a potential critical situation, in the future, that I stopped.(Nurse 4, follow-up)

One nurse explained that the more intense monitoring of patients’ health parameters could also increase their workload. The process of figuring out what caused deviations could be a very lengthy process, with a chat dialogue that could go on for weeks.

In this chat I may respond now, then the patient might respond after 3–4 h. So then I am never done. For example, this patient who suffered a [health incident], it took two weeks before we had a solution. So it depends on how they respond, when they respond, how much time it will take. I mean, if you have 30 min for [the eHealth service] scheduled, it might take three hours. And where should those hours come from?(Nurse 5, follow-up)

3.3.3. Optimizes Population Care

The eHealth user interface for nurses contained both a patient panel view that showed an overview of all patients at the primary care center who used the service and a more detailed view of individual patients. Prior to using the eHealth service, nurses had limited options of gaining an overview of their entire patient population. Thus, they expected that the eHealth service could help them to better prioritize patients according to individual needs, rather than a simple waiting list. They expected that patients most in need of support could be more closely monitored, leading to better population care.

I would be able to directly identify those who are doing worst or those who have contacted the primary care center during the past year. Or I would be able to check the HbA1c and look at all those who are over 53. And just check, is it okay that they are over 53 or is there someone I should follow up with? It would be great to be able to see this.(Nurse 4, baseline)

After having used the eHealth service, nurses confirmed that the overview was helpful in their prioritization, but they also identified challenges in taking on their coaching role, particularly with patients they did not know.

But if I log in, our primary care center has 100 persons, patients, so if I log in everyday to see what is deviating. And I should handle this. Then it will be very difficult to engage in coaching. Of course, I can still do it based on my professional competence, I can understand certain things. But still, it is very difficult when I don’t know the patient, and when I don’t know who I’m talking to.(Nurse 5, follow-up)

4. Discussion

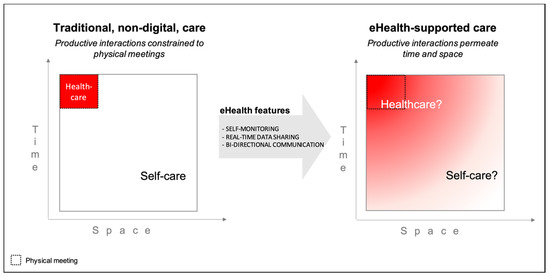

Based on data collected from patients and nurses, our study identified three defining characteristics of productive interactions that supported self-care and healthcare in the context of eHealth use in diabetes care. Productive interactions were characterized by unconstrained access to healthcare, health parameter surveillance, and data-driven feedback. Self-care was supported in terms of health parameter monitoring, self-care knowledge, adequate and timely decisions and actions, and tailoring to individual needs. Healthcare was supported in terms of informed physical meetings and optimized treatment at the individual and population levels. Our findings reveal how the introduction of an eHealth service changes how chronic care is distributed over time and space and between actors. This is illustrated in Figure 1 and further discussed below.

Figure 1.

In traditional, non-digital care, productive interactions are limited in time and space to physical meetings (left-hand side). The introduction of an eHealth service permeates these boundaries, allowing interactions to occur at any time, irrespective of location. Productive interactions in an eHealth ecosystem are thus characterized by unconstrained access, health parameter surveillance, and data-driven feedback, which blurs the boundaries between healthcare and self-care (right-hand side).

4.1. eHealth Perforates the Boundaries of Time and Space

In our findings, productive interactions were characterized by unlimited access, continuous surveillance of health parameters and the expectation of feedback between physical encounters, based on patients’ self-monitoring. The features of the eHealth service (self-monitoring, real-time data sharing, and bi-directional communication) enabled a movement from traditional care, where self-care and healthcare are separated by the boundaries of physical meetings, to an eHealth ecosystem, where the boundaries between self-care and healthcare are blurred. This indicates that the eHealth service disrupted the traditional patterns of interactions between patients and healthcare professionals. In Figure 1, the transcendent nature of the productive interactions is reflected in the blurring of boundaries between self-care and healthcare, where the roles and rules of the interactions are not specified.

With service theories as a lens [9], our findings indicate that the social rules, norms, and routines (i.e., institutions) that previously governed the interactions between patients and healthcare staff in the service ecosystem were obsolete when eHealth was used. Healthcare, as with all institutions, has both formal and informal rules, many of which are implicit [28]. They need to be considered when introducing changes to the system to avoid unintended consequences [28]. Thus, when existing boundaries disappear through the introduction of eHealth, new rules about interaction need to be established [9]. This implies a change in the conditions for productive interactions in the context of eHealth. Yet, our analysis indicates uncertainty about roles and rules of interactions under the new conditions. The sections below discuss how this was manifested in our study and how it compares to previous research.

4.2. Blurred Boundaries between Self-Care and Healthcare

Where does my responsibility start and end? Prior to the introduction of the eHealth service, nurses’ only point of influence on patients was during scheduled visits, at the “point of care”. Healthcare was carried out during visits, and self-care was carried out between visits. After the introduction of the eHealth service, there was no defined “point of care” as nurses could receive new information about an individual patient at any point in time, through shared health data or chat messages. Such a shift may enable healthcare’s ability to offer timely and relevant support for patients in their daily lives, complementing the patient’s own resources in managing their condition [29]. Yet, it also makes the responsibilities less clear, particularly when norms and routines for using eHealth have not been agreed upon. We see several examples of this in our data. For example, participants expressed uncertainty about what type of information they could share and that the chat was used to address “other” questions than merely diabetes-related concerns. Integrity issues were a further complication of the blurred boundaries, particularly related to surveillance of health parameters, with patients being uncertain of how their health data would be used and nurses getting a window into the patients’ broader life without sufficient clarity of their responsibility. Previous research emphasized that written communication requires training [30]. As our findings indicate, training should not focus only on technological mastery but also on developing competency regarding the purpose and content of interaction, as well as managing responsibility. Patients and healthcare professionals may start off with divergent expectations of the “name of the game” of using eHealth. For example, a study showed that while diabetes patients believed that sharing data remotely or before a consultation would allow them to obtain guidance and address unmet needs, healthcare professionals believed that this type of collaboration requires face-to-face meetings [22]. It has previously been suggested that expectations, attitudes, and behaviors of both healthcare professionals and patients need to be addressed to support system change [29,31]. This study points to the need to also consider the rules that govern the behaviors in the system.

4.3. Unclear Expectations about the Level of Engagement

How much am I expected to engage? Nurses, seeing their role as coaches that motivate their patients, emphasized the importance of a trusting relationship with their patients. The eHealth service changed the setting for engaging with patients in two ways. First, as our results indicate, some nurses felt uncomfortable in coaching patients they had not met before because they did not know them well enough. Getting to know patients by means of remote patient monitoring technologies has been described as a complex and dynamic process, whereby nurses synthesize various data sources to generate a mental model of the patient [32]. Given the lack of nonverbal cues, building and maintaining relationships without face-to-face interaction requires enhanced nursing skills, including both relational and technological skills [32]. This relates to findings from a Norwegian study, which found that relationships became more fragile when interacting through an eHealth service [30]. Written communication was described as more vulnerable to misunderstandings and less personal than face-to-face meetings, which in turn influenced the depth of communication. Considering these complications, it has nevertheless been suggested that there are great opportunities for holistic caring by means of text-based communication [33]. The second way in which the eHealth service changed the setting for engaging with patients was by providing nurses with the opportunity to support patients between visits, which was challenging in traditional care. The mere organization of traditional care imposed the norm “out of sight, out of mind”. With the introduction of the eHealth service, the boundaries of the relationship were loosened both in time, because interaction was now possible 24/7, and in space, because the content of the conversations was not defined. For example, as rendered in our results, a chat conversation could extend over a long period of time. This could provide nurses with information that gave them a more holistic understanding of a patient’s situation but simultaneously increased their workload. While this was not explicitly expressed, it possibly also increased their emotional load as they became more aware of the patients’ struggles and needs. With a lack of clear rules and norms for the nurse–patient interaction, the nurses faced a dilemma of determining at what time, in what way, and how much they should monitor and engage in chat dialogues with their patients.

4.4. From Interactions with Individual Patients to Managing Patient Populations

Whom do I interact with/relate to/care for? As our results indicate, the overview of diabetes patients that was presented to nurses in the health professional interface of the eHealth service was new to nurses. As this pilot consisted of few patients, the overview was limited, yet it opened up new experiences of opportunities and challenges. Nurses had access to information that could influence how they prioritized their time between patients. The main opportunity was that this made it easier for them to see who was managing their diabetes well and focus their time on patients in need of support. The nurses were provided with an overview of their “own”, as well as their colleagues’, patients. Thus, they were faced with not only more data from individual patients but also a larger patient volume, which could also lead to uncertainty. It was feared that the increased patient volume would make it challenging for them to practice their coaching role, particularly coaching their colleagues’ patients that they did not know. Having a holistic picture of a patient has been described as essential to facilitating person-centered care and supporting patients in their self-care [32]. In the follow-up survey, patients expressed no concerns about not knowing who surveilled their health data or whom they addressed when sending messages. However, we do not know whether they were aware about this or had such concerns. There was some expressed concern about information security prior to the pilot and previous research indicated that patients want to be able to control whom they share information with [34].

4.5. Implications for Practice

As our results show, eHealth can bring about changes in the productive interactions affecting both self-care and healthcare. For example, improved access to care was both an expectation and a lived experience of using the eHealth service. Indeed, enhanced access is one of the benefits of eHealth that has been pointed out previously [34], not least during the COVID-19 pandemic [35]. Yet, the blurred boundaries between self-care and healthcare call for careful consideration of how new technologies influence tasks, roles, and responsibilities. eHealth services may allow these to be distributed between patients and healthcare staff in new ways. How well the eHealth service is received by its users and how productive the interaction becomes may therefore be dependent on how satisfied nurses and patients are with the distribution of tasks and responsibilities, i.e., if the tasks are perceived as necessary and important, if the work load is reasonable, and if roles are clear [36]. Further, goal orientation (whether interactions are oriented towards what matters to patients) and needs support are important aspects that need to be considered when introducing eHealth services. If optimally supported, eHealth may blur the boundaries between self-care and healthcare in a way that leads to a sense of co-care rather than a fragmented system.

Thus, healthcare organizations need to organize their services in a way that optimally supports the use of eHealth services, both for patients and staff. A Swedish study described how nurses experience the increasing digitalization of primary care as a digital chaos that, apart from its potential advantages, has also greatly increased their workload, caused stress, and reduced job satisfaction [37]. One of the factors that caused stress and concern was the need to constantly redefine their nursing expertise when providing care in a digital environment. While the nurses in our study were mainly positive towards using eHealth, we did identify experiences of uncertainty and increased workload that need to be considered when implementing eHealth services on a larger scale. In particular, our results indicate that digital care interactions cannot be equated with face-to-face interactions in a physical meeting, which implies a necessary redefinition of nurses’ work. Thus, the implementation process may need to consider how to establish “rules of the game” for productive interactions when using eHealth services, in such a way that a virtual boundary in time and space is created, similar to the natural boundaries that are inherent to physical meetings. Previous research indicated that scheduled appointments may also be beneficial when communicating asynchronously [30]. While this may be perceived as contradictory, scheduling time for interacting with the eHealth service could support individuals in their time planning and serve as a reminder for reading and writing messages or completing other eHealth-related tasks. Further, it may be the case that eHealth services are beneficial for limited tasks, such as health parameter surveillance and simple follow-ups, while the nurse’s role as a coach may be best practiced in physical face-to-face meetings. It has been strongly suggested that digital communication should be combined with face-to-face meetings, rather than replacing them [30,38]. Patients who do not need coaching or motivational support from nurses may be duly served by an eHealth technology and a minimal number of care visits, while patients who need this type of support may be best served through face-to-face visits.

4.6. Limitations

We acknowledge that our study has several limitations. We focused on individuals’ perceptions of productive interactions prior to and 6 months post using an eHealth service as a bridge element to mediate their interactions and data sharing. When studying this type of technological service, it is not always evident what behaviors and experiences are related to technology use as opposed to other factors. Moreover, as it was a pilot, the eHealth service was not introduced to all staff at the involved PCCs. A scaled-up implementation would possibly have implied a more thorough re-organization of healthcare services, potentially involving other staff than nurses. Thus, as transferability of case studies is already limited by design, we emphasize that our findings should be interpreted with some caution.

This study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there are indeed examples of resilient healthcare systems that were able to quickly transition to more digital health in diabetes care [35], many, like the PCCs that ran the eHealth pilot we used as our case, did not manage to uphold the recruitment to the project as planned. Thus, the main shortcoming of our study is the limited number of participants. However, qualitative data from both interviews and questionnaires were used and included the perspectives of both patients and nurses. Qualitative studies are well suited to generate new hypotheses, which we believe our study contributes with. While interview data allow for rich descriptions from individual participants, questionnaires enable the collection of data from more individuals. Hence, our results contain richer descriptions from the perspectives of nurses, which is illustrated in the selection of quotes. It has been argued that it is difficult to fulfil excellence criteria for qualitative research with questionnaire data [39]. While we acknowledge that our questionnaire data, consisting of patients’ free text answers to open-ended questions, are limited in their depth, we do believe that the combination of these data with the interview data allows us to “meaningfully interconnect literature, research questions/foci, findings, and interpretations with each other” [40]. Malterud et al. suggested the concept information power to determine the adequate sample size in qualitative research [41]. The more relevant information that can be extracted from a sample (high information power), the fewer participants needed. A study that is supported by theory and has a narrow study aim and strong interview dialogue with participants that are highly specific for the aim, ideally with longitudinal in-depth exploration of narratives, will need the least number of participants. In our sample, the information power was stronger in the nurse interviews than the elicited patient data, implying that we may not have captured the complete spectrum of patient experiences that allows for a full characterization of productive interactions in the context of eHealth use in diabetes care. Hence, having more patient data could have contributed to more detailed and nuanced findings.

Our sample covered individuals with one of the most common chronic conditions (diabetes Type 2) affecting public health. Yet, when transferring our findings to other settings, contextual factors need to be considered, such as the study setting and the eHealth technology itself. We acknowledge that design features of the eHealth service, which were not explored in detail in this study, may have an influence on productive interactions. Another eHealth service with other features may have elucidated different aspects of productive interactions. This is something we have explored in an earlier study where we found that the very same features of an eHealth service could simultaneously lead to satisfaction and frustration among the patients who used the service [42]. This would likely also influence the way they use the service and hence the productive interactions with healthcare. While our aim was to gain a general understanding of the influence of eHealth on productive interactions between patients and healthcare professionals, we encourage more in-depth studies considering contextual factors as well as design features in future research.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed that the introduction of an eHealth service for self-monitoring and digital communication in primary care implies institutional changes to the healthcare ecosystem. Based on the studied context, we found that the use of eHealth not only entailed a disruption in terms of new tasks but also caused uncertainty about the social rules and norms of digital interaction. We believe that the attainment of a sustainable eHealth ecosystem will require healthcare to acknowledge eHealth as a disruptive change that may require re-organization to optimally support the use of eHealth services for both patients and staff, which includes agreement on new routines, as well as social interaction rules for digital communication. Explicitly discussing the name of the game, i.e., the main purpose of the eHealth service and its use, could be a feasible way to maximize the chances that the eHealth ecosystem is optimized to attain set goals, without leading to unintended consequences. More long-term studies will be needed to establish best practices for a sustainable eHealth ecosystem in chronic care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; data curation, C.W.; methodology, all authors; investigation (interviews), C.W., T.S., K.P.H.; formal analysis (questionnaire data), C.W., U.v.T.S., K.P.H., T.S.; formal analysis (interview data), T.S., K.P.H.; visualization, U.v.T.S., C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W., with contributions from all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; project administration, T.S., C-G.Ö.; funding acquisition, U.v.T.S., C.W., K.P.H., C-G.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research, including the APC, was funded by the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship, Research & Charity, grant number 20170012. C.W. was partially funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, grant number 2017-01451. C-G.Ö. and the pilot were funded by Sweden’s innovation agency Vinnova, grant number 2017-05319.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to the study participants and the primary healthcare centers that contributed to this research. In particular, we thank: Lars Gustafsson and Kaija Seijboldt for leading the eHealth pilot, as well as their input on survey design and interview guides. We also thank our research colleagues Klas Karlgren and Henna Hasson for their contributions to the survey design, and Sivan Menczel for her contributions to the survey administration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Von Korff, M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996, 74, 511–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff. Clin. Pract. 1998, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, A. Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions Building the house of care. Lond. Kings Fund 2013, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Batalden, M.; Batalden, P.; Margolis, P.; Seid, M.; Armstrong, G.; Opipari-Arrigan, L.; Hartung, H. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldstad, Ø.D.; Johnson, J.K.; Margolis, P.A.; Seid, M.; Höglund, P.; Batalden, P.B. Networked health care: Rethinking value creation in learning health care systems. Learn. Health Syst. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalden, P. Getting more health from healthcare: Quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction—An essay by Paul Batalden. BMJ 2018, 362, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H. Organizing Care for Patients with Chronic Illness Revisited. Milbank Q. 2019, 97, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. What is e-health? J. Med. Internet Res. 2001, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, A.; Monda, A. Sustainable value co-creation and digital health: The case of trentino eHealth ecosystem. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, P.M.; Greenwood, D.A.; Paterniti, D.A.; Ward, D.; Miller, L.M.S. The eHealth enhanced chronic care model: A theory derivation approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimison, H.; Gorman, P.; Woods, S.; Nygren, P.; Walker, M.; Norris, S.; Hersh, W. Barriers and drivers of health information technology use for the elderly, chronically ill, and underserved. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2008, 175, 1–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, B.A.; Turner, J.W.; Robinson, J.D.; Angelus, P.; Hu, T.M.J. Communication plays a critical role in web-based monitoring. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2009, 3, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.D.; Warisse Turner, J.; Levine, B.; Tian, Y. Expanding the walls of the health care encounter: Support and outcomes for patients online. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, L.S. A Taxonomic Integrative Review of Short Message Service (SMS) Methodology: A Framework for Improved Diabetic Outcomes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildevuur, S.E.; Simonse, L.W.L.; Groenewegen, P.; Klink, A. Information and communication technology enabling partnership in person-centred diabetes management: Building a theoretical framework from an inductive case study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voruganti, T.; Grunfeld, E.; Makuwaza, T.; Bender, J.L. Web-Based Tools for Text-Based Patient-Provider Communication in Chronic Conditions: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borries, T.M.; Dunbar, A.; Bhukhen, A.; Rismany, J.; Kilham, J.; Feinn, R.; Meehan, T.P. The impact of telemedicine on patient self-management processes and clinical outcomes for patients with Types I or II Diabetes Mellitus in the United States: A scoping review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, K.R.; Ali, M.K.; Zhou, X.; Ng, B.P.; Jawanda, S.; Proia, K.; Zhang, X.; Gregg, E.W.; Albright, A.L.; Zhang, P. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to manage diabetes: Has the evidence changed since 2008? Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1557–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, R.; Kalhori, S.R.N.; Ghazisaeidi, M.; Fatehi, F. Conformity of Diabetes Mobile apps with the Chronic Care Model. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2019, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruque, L.I.; Wiebe, N.; Ehteshami-Afshar, A.; Liu, Y.; Dianati-Maleki, N.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Manns, B.J.; Tonelli, M. Effect of telemedicine on glycated hemoglobin in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ 2017, 189, E341–E364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.D.; Malabu, U.H.; Callander, E.J.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Considerations for the development of mobile phone apps to support diabetes self-management: Systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradway, M.; Morris, R.L.; Giordanengo, A.; Årsand, E. How mHealth can facilitate collaboration in diabetes care: Qualitative analysis of co-design workshops. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew-Sam, N.; Chib, A. How Do Smart Device Apps for Diabetes Self-Management Correspond with Theoretical Indicators of Empowerment? An Analysis of App Features. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2019, 35, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drincic, A.; Prahalad, P.; Greenwood, D.; Klonoff, D.C. Evidence-based Mobile Medical Applications in Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 943–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Bekräftade Fall i Sverige—Daglig Uppdatering [Confirmed Cases in Sweden—Daily Updates]. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/statistik-och-analyser/bekraftade-fall-i-sverige/ (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Polansky, D.; Novak, P.; Foltin, C.; Polivaev, D. FreeMind v.1.0.1—Free Mind Mapping and Knowledge Building Software Copyright © 2000–2013, Licensed under GNU General Public License; 2014. Available online: https://sourceforge.net/projects/freemind/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Ostrom, E.; Hess, C. A Framework for Analyzing the Knowledge Commons. In Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice; Hess, C., Ostrom, E., Eds.; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thiele Schwarz, U. Co-care: Producing better health outcome through interactions between patients, Care providers and information and communication technology. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2016, 29, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.S.; Karlsen, B.; Graue, M.; Oftedal, B. The influence of an eHealth intervention for adults with type 2 diabetes on the patient–nurse relationship: A qualitative study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M. What ‘Patient-Centered’ Should Mean: Confessions of An Extremist. Health Aff. 2009, 28, w555–w565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, D.A.; Stacey, D.; Momtahan, K.; Gifford, W.; Doucet, S.; Etowa, J.B. Getting a Picture: A Grounded Theory of Nurses Knowing the Person in a Virtual Environment. J. Holist. Nurs. 2017, 35, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, K.M.; Sandman, L.; Nyström, M.; Stockelberg, D.; Broström, A. Caring Through Web-Based Communication: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Nursing Intervention to Create Holistic Well-Being Among Patients with Hematological Disease. J. Holist. Nurs. 2018, 36, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, K.; Dack, C.; Ross, J.; Michie, S.; May, C.; Stevenson, F.; Farmer, A.; Yardley, L.; Barnard, M.; Murray, E. Digital health interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes: Qualitative study of patient perspectives on diabetes self-management education and support. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alromaihi, D.; Alamuddin, N.; George, S. Sustainable diabetes care services during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 166, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Roczniewska, M.; Pukk Härenstam, K.; Karlgren, K.; Hasson, H.; Meczel, S.; Wannheden, C. The work of having a chronic condition: Development and psychometric evaluation of the Distribution of Co-Care Activities (DoCCA) Scale. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Öberg, U.; Orre, C.J.; Isaksson, U.; Schimmer, R.; Larsson, H.; Hörnsten, Å. Swedish primary healthcare nurses’ perceptions of using digital eHealth services in support of patient self-management. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, J.; Bhatt, R.; Ferm, A. Older people and rural eHealth: Perceptions of caring relations and their effects on engagement in digital primary health care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, scs.12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaDonna, K.A.; Taylor, T.; Lingard, L. Why open-ended survey questions are unlikely to support rigorous qualitative insights. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight a “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannheden, C.; Stenfors, T.; Stenling, A.; von Thiele Schwarz, U. Satisfied or Frustrated? A Qualitative Analysis of Need Satisfying and Need Frustrating Experiences of Engaging with Digital Health Technology in Chronic Care. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).