Practical Functioning of a Sustainable Urban Complex with a Park—The Case Study of Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Studied Area of the Stavros Niarchos Park and the District of Kallithea

3.1. The Stavros Niarchos Park

3.2. The Stavros Niarchos Park Versus Greenery in Athens

3.3. The District of Kallithea—Population and History

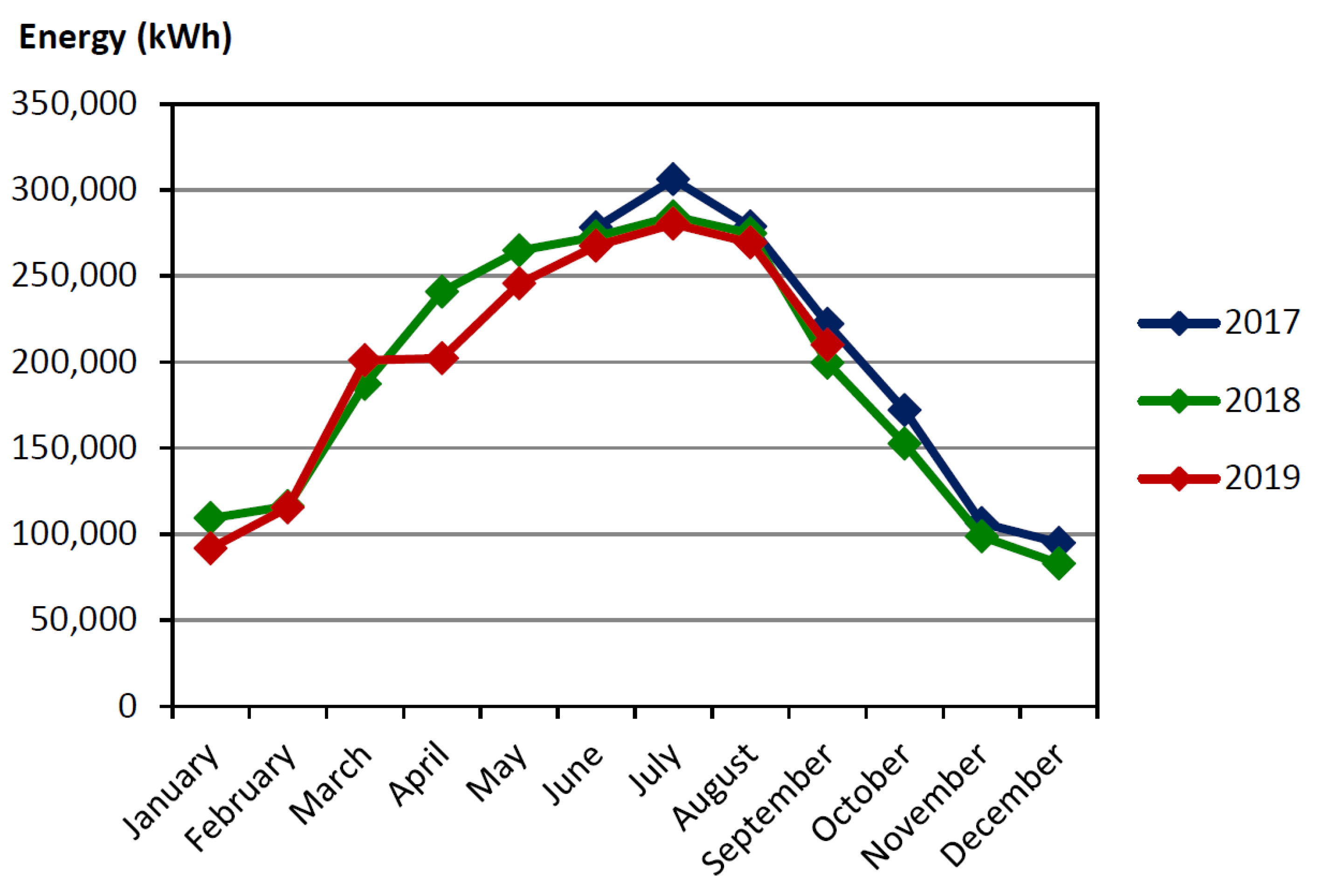

4. ‘Sustainability’ of the SNFCC’s Structure—The Efficiency of the Canopy Panels

- The photovoltaic panels on the Energy Canopy were activated in May, meeting 27.98% of the SNFCC energy consumption needs from June to December 2017 [40];

- ‘The operation of critical systems, such as air conditioning, were optimized to minimize power consumption. Natural gas consumption was reduced by 21% (comparison periods: May to December 2016 and 2017)’ [17];

- ‘Thanks to proper planning and streamlining, a 23% reduction in irrigation consumption was achieved’ [19] (comparison periods: April to September 2016 and 2017).

- ‘SNFCC’s energy efficiency initiatives result in a 40% energy reduction compared to what a similar building complex would consume without their implementation’ [40];

- ‘Energy efficiency initiatives contribute to annual energy savings of 7.4 GWh, equivalent to ~2750 tons of CO2 and ~EUR 0.6 million saved annually’ [41].

5. Results

5.1. The Number of SNFCC’s Visitors

5.2. ‘Sustainability’ of the SNFCC’s Program—The Number of Events and Their Role in Popularizing Cultural and Natural Heritage of Greece

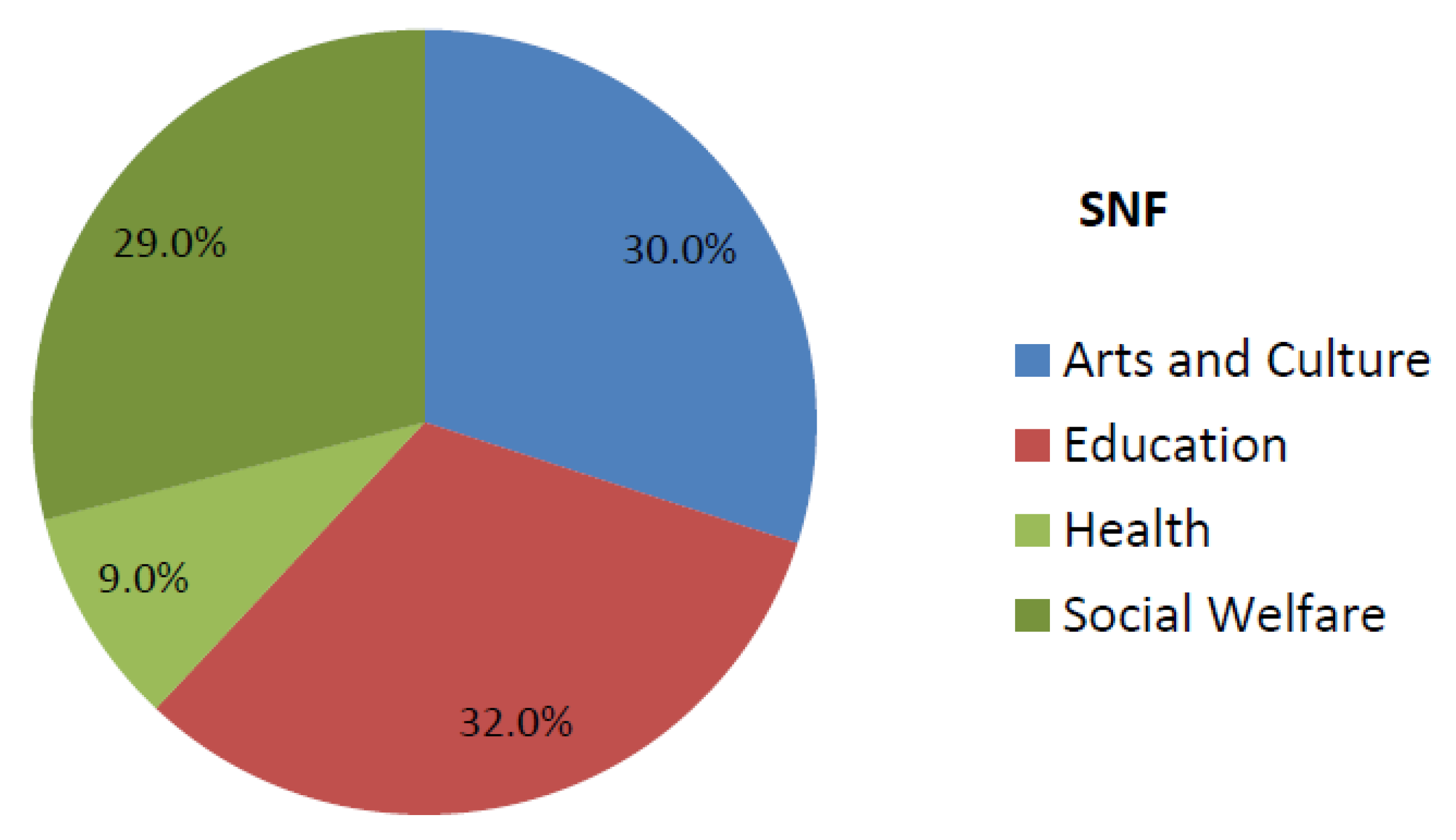

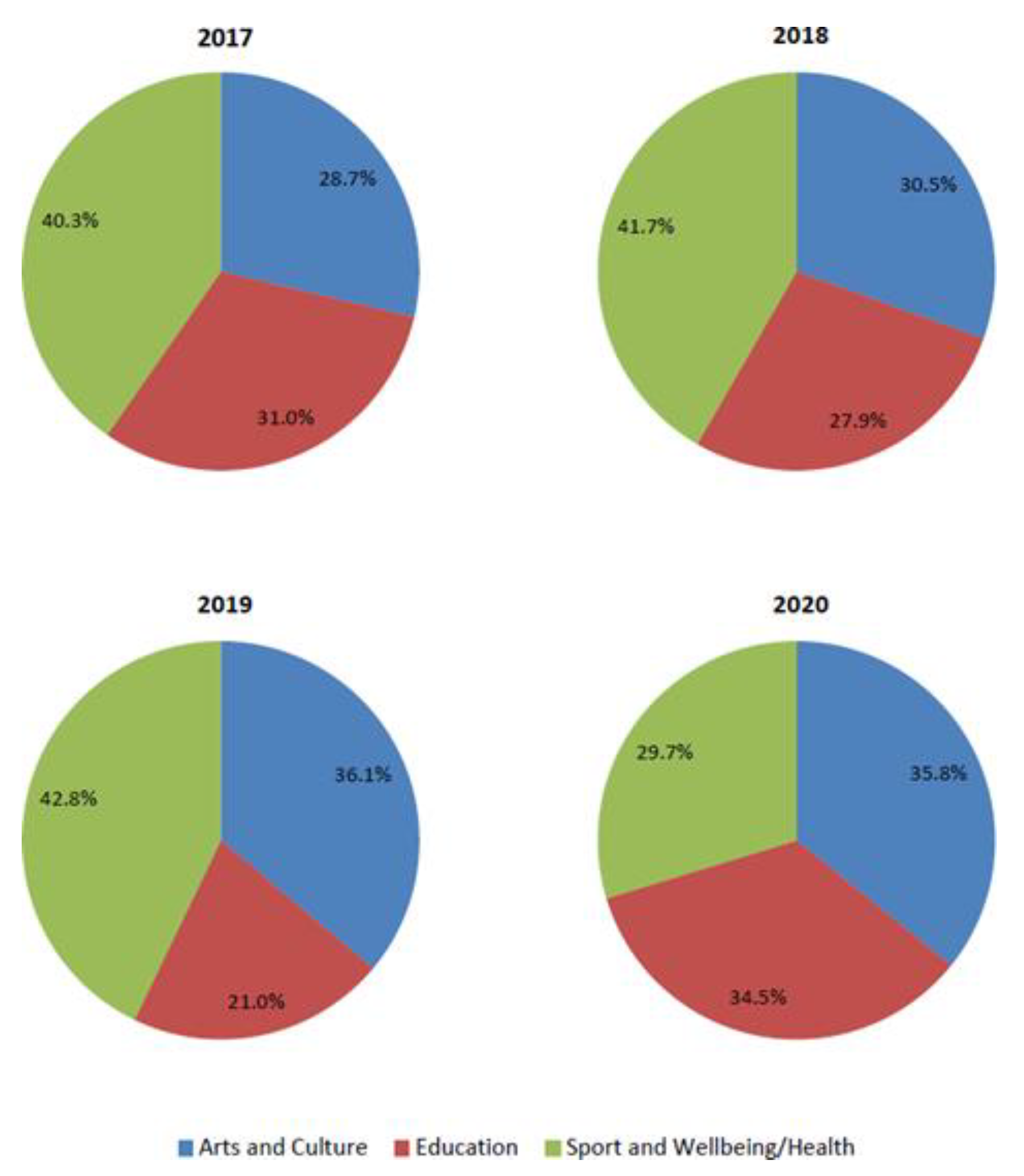

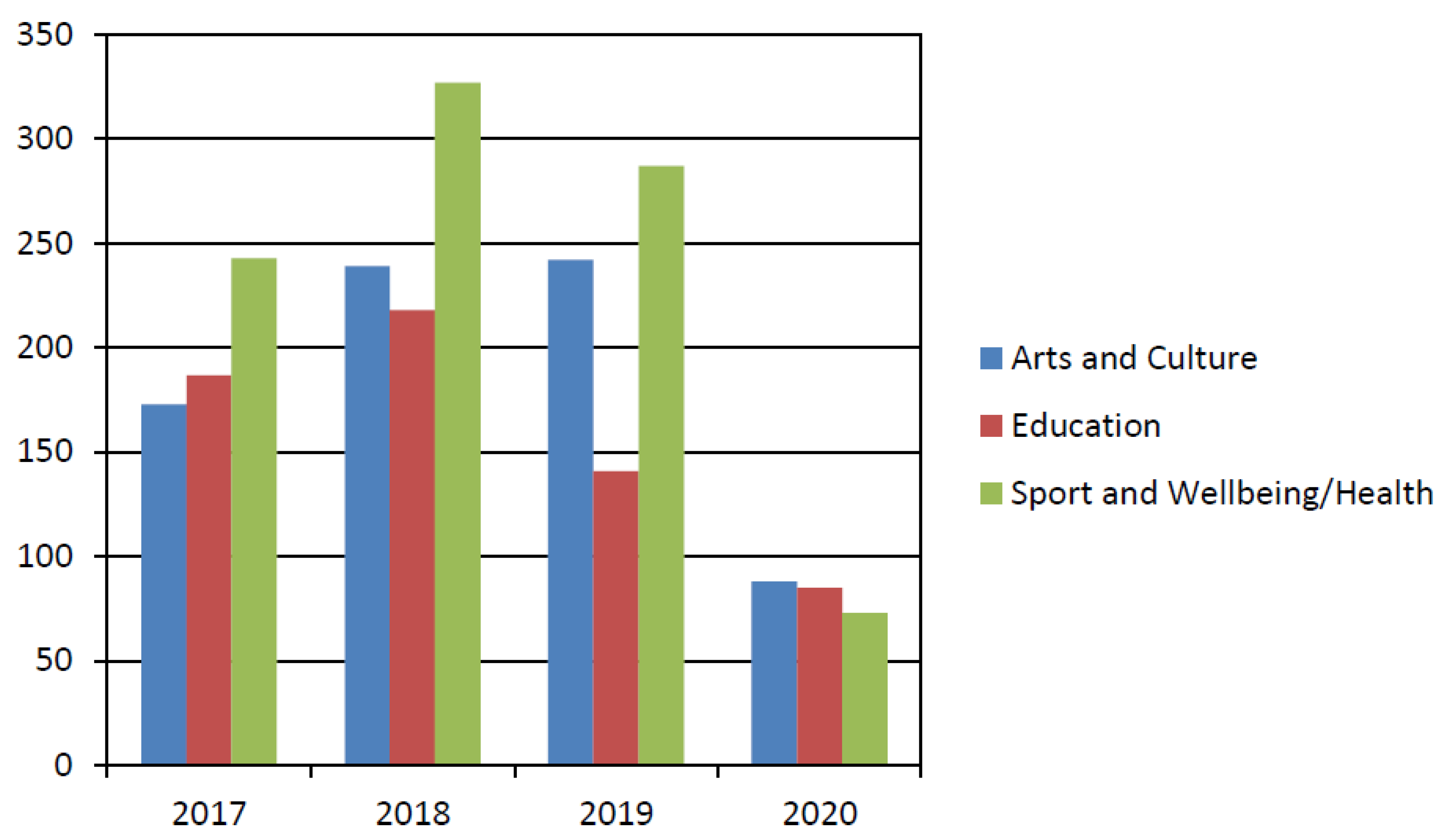

- The proportions of grants donated by the SNF (Figure 12) in the various areas (Art and Culture—30%, Education—32% and Health and Social Welfare—the last two areas account for 38% jointly) are comparable to the proportions between the three categories of events organized by the SNFCC over the years (Figure 13): Art and Culture (from 28.7% to 36.1%), Education (from 21% to 34.5%) and Sport/Wellbeing/Health (between 29.7% and 42.9%). This confirms the consistent policy of the foundation and a conscientious approach to full transparency in financial management [47];

- The obtained data on all events and the proportions between the three distinguished categories (Figure 14 and Figure 15) highlight those which enjoy the most popularity and provide a response to the needs of the community. The particularly high number of sports events (in 2019, they accounted for 70.5%, while in 2020 for 69.1% of all events) confirms the growing interest in the facility and the increased frequency of visits to the park. Higher demand for educational services confirms the immense contribution by the SNFCC in terms of extending the residents’ knowledge and inspiring their interests. This applies, for instance, to the assistance targeted at seniors (computer training, activities for persons experiencing problems with memory, etc.). The SNFCC project was designed to achieve a broad, lasting, and positive social impact. Its diverse cultural, educational, and sports programs have particularly focused on the needs of the young and the elderly people as a way of ensuring public welfare [48,49]. Such activities are highly relevant because of the effects of the crisis in Greece;

- The creation of the SNFCC with the Park is a factor contributing to the improvement of the quality of residents’ life (health and wellbeing); for instance, by offering sports activities, which have a positive effect on physical and mental health, general fitness, mobility, and functionality. The prevalence of sports events in the scheme (Figure 16) shows that many residents have been persuaded to adopt a healthy lifestyle and engage in regular exercise;

- The social and cultural aspects of the sustainable urban improvements are fulfilled during practical functioning of the SNFCC. Its program focusses on providing cultural and ecological stimuli and opportunities for learning to everybody;

- Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way in which the citizens use the SNFCC complex. The gradual increase in the number of the events organized by the SNFCC in the period 2017–2019 was unfortunately followed by a drop in 2020—the number of events corresponded to only 37.8% of the average value for 2017–2019. The lectures organized in 2020 touched upon pertinent topics and aimed at helping the residents whose mental health [50] had deteriorated as a result of the pandemic, i.e., ‘Challenges in an ever-changing landscape’, ‘The limitation of our social life’, ‘Mentally resistant during quarantine’. Owing to the flexible approach, program modification, and its releases on the Internet, the SNFCC has received subsequent awards in 2020 for its operations.

6. Discussion

- The lack of updated data on the population of the Kallithea district in 2020—the data from 10 years ago are still being used (from the last the population census from 16 March 2011);

- No detailed information on the efficiency of the panels from October 2019 to December 2020 or on the number of persons visiting the site in 2020 could be obtained from the SNFCC;

- The limited availability of information in the English language.

7. Conclusions

- The SNFCC interdisciplinary project plays an important role in popularizing the cultural and natural heritage of Greece;

- The fact that the SNFCC project has met high ecological standards makes it an endeavor of European relevance. It is one of the leading examples of environmental sustainability across three levels: design and construction, operation, footprint in the local ecosystem and social welfare (‘sustainable’ program). The best practices in terms of environmental standards implemented at the SNFCC guarantee the sustainability of its operations. The ecological aspects of sustainability performed in the SNFCC contribute to stability of the climate in the neighborhood, improvement in the quality of air, and the renewal of biodiversity. Tangible benefits on the local ecosystem are already apparent in the Park. The Kallithea district has become a more inclusive, safe, and sustainable settlement for inhabitants;

- The sustainable project of the SNFCC, which fulfils the urban ecology criteria, has been very well received by the visitors—citizens and tourists alike. The sustainability of this complex extends beyond the structure of the buildings and the SN Park. The SNFCC’s practical functioning thanks to the ‘sustainable programme’ contributes to other benefits such as the health and wellbeing of residents, quality and accessibility of education, and reduction in inequalities [56]. It offers green and cultural education to all visitors, especially children and youth;

- The development of high-quality buildings and the SN Park is a factor contributing to the improvement of the quality of urban space and the quality of residents’ lives. It also contributes to the increased value of the neighboring areas in the Kallithea district and influences a property boom [53]. The sports activities organized at the site contribute to the improvement of public health and help to promote a healthy lifestyle;

- The SN Park continued to operate during the pandemic in 2020, which was a crucial element for citizens during this difficult time;

- The SN Park is an approach to create a deep link between nature and society according to urban political ecology. In this social and ecological process, local plants became a second nature based on Greek landscapes;

- Introduced Ecosystem Services in the SNFCC project moderate natural phenomena (flood control, water purification, and climate regulation);

- Provided in the SN Park are Cultural Ecosystem Services benefits (e.g., recreation, physical and mental health, aesthetic enjoyment), which may contribute to fostering social cohesion. They can be essential for human wellbeing and can contribute to a sense of place (topos). In the SN Park, there are a few urban spaces indicated on the map (Figure 4) which play an important role for the local community.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruble, B.A. The Challenges of the 21st Century City. Urban Sustainability Laboratory. Wilson Center. Available online: www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/the-challenges-the-21st-century-city (accessed on 6 December 2012).

- Papageorgiou, M.; Gemenetzi, G. Setting the grounds for the Green Infrastructure in the metropolitan areas of Athens and Thessaloniki: The role of green space. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 8, 82–92. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325897837_Setting_the_grounds_for_the_Green_Infrastructure_in_the_metropolitan_areas_of_Athens_and_Thessaloniki_the_role_of_green_space (accessed on 12 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Cranz, G.; Boland, M. Defining the Sustainable Park: A Fifth Model for Urban Parks. Landsc. J. 2004, 23, 102–120. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250231365_Defining_the_Sustainable_Park_A_Fifth_Model_for_Urban_Parks (accessed on 12 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; van den Bosch, M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; van den Bosch, C.K. Species richness in urban parks and its drivers: A review of empirical evidence. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 17, 305–327. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257671090_Species_richness_in_urban_parks_and_its_drivers_A_review_of_empirical_evidence (accessed on 12 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green Infrastructure: Smart Conservation for 21st Century. Renew. Resour. J. 2002, 20, 12–17. Available online: https://www.merseyforest.org.uk/files/documents/1365/2002+Green+Infrastructure+Smart+Conservation+for+the+21st+Century.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Smets, J.; De Blust, G.; Verheyden, W.; Wanner, S.; Van Acker, M.; Turkelboom, F. Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure: From Boundary Concept to Collective Action. Sustainability 2020, 12, 101017. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10107 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Drapella-Hermansdorfer, A. Współczesny Park Miejski w Europie. Available online: https://docplayer.pl/3164332-Wspolczesny-park-miejski-w-europie.html (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Wolski, P. Współczesny park miejski w Europie. In Wizja Rozwoju Wojewódzkiego Parku Kultury i Wypoczynku im. Gen. Jerzego Ziętka. Materiały Konferencyjne; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://slaskie.pl/images/wpkiw/pw_wpme.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Zachariasz, A. Współczesne kierunki i tendencje w projektowaniu parków publicznych. Nauka Przyr. Technol. 2009, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariasz, A. Zieleń jako Współczesny Czynnik Miastotwórczy ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Roli Parków Publicznych; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332080375_Zielen_jako_wspolczesny_czynnik_miastotworczy_ze_szczegolnym_uwzglednieniem_roli_parkow_publicznych (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Zachariasz, A. A Park in a Small Town. On the Value of Place and Maintenance of Tradition. In 7ULAR: Middle-Sized Cities of Tomorrow; Juzwa, N., Sulimowska-Ociepka, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2013; pp. 209–215. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343006692_A_PARK_IN_A_SMALL_TOWN_ON_THE_VALUE_OF_PLACE_AND_MAINTENANCE_OF_TRADITION (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Makowska, B. Ogrody przy muzeach w Paryżu/The gardens near museums in Paris. Czas. Tech. 2010, 5-A, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, B. Parki rzeźb w Norwegii/The Sculpture Parks in Norway. Czas. Tech. 2012, 2-A, 203–208. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/31199/file/suwFiles/MakowskaB_ParkiRzezb.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Schneider-Skalska, G. Witruwiusz—prekursor projektowania zrównoważonego. Czas. Tech. 2009, 1-A, 127–131. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/33761/file/suwFiles/SchneiderSkalskaG_WitruwiuszPrekursor.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Newhouse, V. Chaos and Culture: Renzo Piano Building Workshop and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens; Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Awards. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/awards (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center 2017 Report. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/sites/default/files/sitefiles_2019-07/apologismos_eng_1.7.19.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- SNFCC Impact Study Report for SNF Board of Directors. Available online: https://www.snf.org/media/4960627/SNFCC-Impact-Study-Detailed-Report-EN.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Stavros Niarchos Foudation Cultural Center. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Pafi, M.; Siragusa, A.; Ferri, S.; Halkia, M. Measuring the Accessibility of Urban Green Areas: A Comparison of the Green ESM with Other Datasets in Four European Cities; JRC Technical Reports; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC102525/190916_siragusa_%20jrc_techrep_accessibility_online.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Kalfa, F.; Kalogirou, N. Quality through Sustainable Practices during the Design and Construction Phase—The case of the SNFCC. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asprogerakas, E. Strategic Planning and Urban Development in Athens. The Current attempt for Reformation and future challenges. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Urban Planning and Design Symposium, Nicosia, Cyprus, 13 May 2016; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320695579_Strategic_Planning_and_Urban_Development_in_Athens_The_Current_attempt_for_Reformation_and_future_challenges (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Sardianou, E.; Leonti, A. Applying the Contingent Valuation Method in Assessing Urban Parks: The Case of Niarchos in Greece. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2019, 362, 1–6. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337289250_Applying_The_Contingent_Valuation_Method_in_Assessing_Urban_Parks_the_Case_of_Niarchos_in_Greece (accessed on 12 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Siti, M.; Floropoulou, E. Reconsidering Sustainable Mobility Patterns in Cultural Route Planning: Andreas Syngrou Avenue, Greece. Heritage 2019, 2, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah Nevins & Associates. Available online: https://www.dnalandscape.com/athens.html (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Clark, D. Green Space per Inhabitant in the City of Athens in Greece in 2018. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/860773/green-areas-per-inhabitant-in-athens-in-greece (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Feltynowski, M.; Kronenberg, J.; Bergier, T.; Kabisch, N.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Strohbach, M.W. Challenges of urban green space management in the face of using inadequate data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 56–66. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1618866717304569 (accessed on 12 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Forde, T. Satellite Images Ranks Europe’s Greenest (and Not so Green) Cities. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/883707/satellite-images-ranks-europes-greenest-and-not-so-green-cities (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- London ‘Greenest City’ in Europe. Available online: https://www.edie.net/news/6/London--greenest-city--in-Europe-/ (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Prajsner, A. Które z Naszych Miast jest Najbardziej “Zielone”? Available online: https://forsal.pl/artykuly/1027174,ktore-z-naszych-miast-jest-najbardziej-zielone.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Dímos Kallithéas. Municipality in Attica. Available online: https://citypopulation.de/en/greece/attiki/4801__d%C3%ADmos_kallith%C3%A9as/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Kallithea. Euromed. Available online: http://www.reseau-euromed.org/en/ville-membre/kallithea-2/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Wikipedia. Population Density in Athens. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Population_Density_in_Athens.PNG (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Daniels, E. The Area I Live in: Kallithea. Available online: https://slideplayer.com/slide/13793946/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Wikipedia. 1896 Summer Olympics. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1896_Summer_Olympics (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Europa dla Obywateli. Available online: https://europadlaobywateli.pl/partnerzy/municipality-of-kallithea// (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Ateny Klimat (Grecja). Available online: https://pl.climate-data.org/europa/grecja/ateny/ateny-7/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Weather Atlas. Monthly Weather Forecast and Climate Athens, Greece. Available online: https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/greece/athens-climate#daylight_sunshine (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Surface Air Temperature for December 2019, Implemented by ECMWF, Copernicus 2019. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/surface-air-temperature-december-2019 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- SNFCC. Energy. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/energy (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- SNFCC. Impact Study Report for SNF Board of Directors. Available online: https://www.snf.org/media/4963854/SNFCC-Impact-Study-Report-FINAL-EN.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center SNFCC. Three Successful Years—6.3 Million Visitors in 2019. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/news/stavros-niarchos-foundation-cultural-center-three-successful-years-63-million-visitors-2019 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- SNFCC. Monthly Booklets. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/monthlyevents (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- An Innovative Collaboration Reimagines and Reactivates Public Space for a New Era, from New York to Athens. Available online: https://www.snf.org/en/newsroom/news/2020/12/an-innovative-collaboration-reimagines-and-reactivates-public-space-for-a-new-era (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- SNFCC. Culture. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/snfcc/our-work/culture (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Hodor, K.; Przybylak, Ł.; Kuśmierski, J.; Wilkosz-Mamcarczyk, M. Identification and Analysis of Problems in Selected European Historic Gardens during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1332. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1332 (accessed on 1 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- SNFCC. Close Collaboration between the SNFCC and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/news/close-collaboration-between-snfcc-and-stavros-niarchos-foundation/1240 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Visitors to SNFCC Reach 5.3 Million in 2018. Available online: https://www.ekathimerini.com/238024/article/ekathimerini/life/visitors-to-snfcc-reach-53-million-in-2018 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- The Stavros Niarchos Foundation. Available online: https://www.efc.be/member-post/stavros-niarchos-foundation-2/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- SNFCC. Pandemic: Challenges in an Ever-Changing Landscape. Available online: https://www.snfcc.org/en/PandemicLectures (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Oberfrancová, L.; Legény, J.; Špaček, R. Critical Thinking in Teaching Sustainable Architecture. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2019, 17, 127–133. Available online: http://www.wiete.com.au/journals/WTE&TE/Pages/Vol.17,%20No.2%20(2019)/01-Spacek-R.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center. Presentation it European Cloud Plenary 18 March 2014. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/Europeana/presentation-it-europeana-cloud-plenary18314 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Gkinni, Z.; Tsaroucha, C.; Sarris, N. The National Library of Greece: Moving into a new era. In Proceedings of the World Library and Information Congress, 83rd IFLA General Conference and Assembly, Wrocław, Poland, 19–25 August 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340447525_The_National_Library_of_Greece_moving_into_a_new_era (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Kampouris, N. Over Five Million Visit Athens’ Stavros Niarchos Cultural Center in 2018. Available online: https://greekreporter.com/2019/02/25/over-five-million-visit-athens-stavros-niarchos-cultural-center-in-2018/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Greek City Time. Over 6.3 Million People Visit Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre in 2019. Available online: https://greekcitytimes.com/2020/01/30/over-6-3-million-people-visit-stavros-niarchos-foundation-cultural-centre-in-2019/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Andriopoulou, E. The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center: A Case Study of a Public-Private Partnership for the Benefit of Society. Available online: https://www.wtflucerne.org/snfcc-as-ppp-success-story (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Markou, M. Renovation Projects at Faliro Bay. Available online: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/faliro-bay/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Fotiadi, I. The SNFCC in Athens Local Improvement Rekindles a District. Goethe Institut. Available online: https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/ges/eu2/rhr/21017619.html (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Makowska, B. Green elevations and roofs of the buildings (the 5th elevation) in 21st century cities. In Future of the Cities—Cities of the Future; Gyurkovich, J., Wójcik, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2014; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, B. Ogrody i Parki w Miastach Hiszpanii/Gardens and Parks in Spain Cities. Czas. Tech. 2012, 6, 235–243. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/30944/file/suwFiles/CzasopismoTechniczne_z.19.Architektura_z.6-A.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- How Many Buildings in the World are LEED Platinum Certified? Design Ideas for the Built World. Available online: https://caddetailsblog.com/post/how-many-buildings-in-the-world-have-become-leeds-platinum-certified (accessed on 12 October 2020).

| Year | Population of the Kallithea District | Density (Habitants/km2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 117,319 | 24,699 |

| 1991 2 | 116,731 | 24,575 |

| 2001 3 | 115,150 | 24,242 |

| 2011 4 | 100,641 | 21,188 |

| 2020 5 | 100,641 | 21,188 |

| Year | The SNFCC’s Visitors | Estimate Average Number of Visitors Per Day |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 1 | 3,100,000 | 3,100,000: 365 days = 8493 |

| 2018 2 | 5,300,000 | 5,300,000: 365 days = 14,521 |

| 2019 3 | 6,300,000 | 6,300,000: 365 days = 17,260 |

| average 2017–2019 | 4,900,000 | 13,425 |

| Arts and Culture | Education | Sport and Wellbeing/Health |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Music, concert | 56 | 62 | 68 | 25 |

| Cinema (Park Your Cinema and Park Your Cinema Kids) | 44 | 45 | 24 | 6 |

| Theatre, performance, spectacle | 125 | 217 | 245 | 45 |

| Exhibitions | 7 | 12 | 20 | 13 |

| Dance—performance | 10 | 9 | 23 | 2 |

| Festival, carnival, conference, forum | 6 | 5 | 11 | 4 |

| Talks/learning, lecture, reading club, reading seminar, course and workshop, etc. | 774 | 1431 | 904 | 342 |

| Sport and wellbeing, walk in the park, virtual tour in the park, gardening for the family in the Park, etc. | 1452 | 2547 | 3124 | 978 |

| Total events (with total number of recurring events) | 2474 | 4328 | 4419 | 1415 |

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events | 2474 | 4328 | 4419 | 1415 |

| Number of participants 2 | 258,973 | 713,667 | 963,000 | ~336,015 3 |

| Event | Number of Films on the Internet | Number of Viewers |

|---|---|---|

| Music, concerts | 22 films (29 December 2020) | 6109 views |

| Cinema | 0 | 0 |

| Theater and performances | 6 films (4 December 2020) | 1696 views |

| Exhibitions | 0 | 0 |

| Dance | 0 | 0 |

| Festival, carnival, conference | 0 | 0 |

| Talks/learning, lectures, reading club, reading, etc. | Reading for kids: 43 films (22 December 2020) 76 films (18 December 2020) Educational program for kids: 88 films (18 December 2020) | 2786 views 2333 views 4621 views |

| Sport and wellbeing, walk in the park, virtual tour in the park | Tour of the SNFCC: 8 films (5 November 2020) walk in the Park: 3 films (3 November 2020) Sport 1: 57 films (9 November 2020) | 898 views 550 views 8662 views 1 |

| Total | 303 | 27,655 |

| Year: 2020 | Yoga | Pilates | Tai Chi | Fit Kids | Exercise and Health | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number views | 2270 | 3268 | 991 | 1009 | 1124 | 8662 |

| Number of films | 12 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 57 |

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events and activities | 2942 | 3743 | 3608 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makowska, B. Practical Functioning of a Sustainable Urban Complex with a Park—The Case Study of Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095071

Makowska B. Practical Functioning of a Sustainable Urban Complex with a Park—The Case Study of Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095071

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakowska, Beata. 2021. "Practical Functioning of a Sustainable Urban Complex with a Park—The Case Study of Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095071

APA StyleMakowska, B. (2021). Practical Functioning of a Sustainable Urban Complex with a Park—The Case Study of Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens. Sustainability, 13(9), 5071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095071