Abstract

Stakeholder opposition is reported as a central aspect of public-private partnership (PPP) failure; however, it has not gained much attention in either tourism or general PPP studies. Therefore, this study seeks to explore stakeholder opposition and develop a measurements scale of opposition in tourism PPP projects. An exploratory-sequential mixed methods approach is employed to holistically understand the subject. The results confirmed that lack of perceived value, relational strength, stakeholder management approach, and a conflict (and power) management mechanism, in addition to inadequate capabilities of stakeholders and poor experience outcomes, are antecedents of opposition to tourism PPP projects. Other notable results and their implications for theory and practice are included in the article.

1. Introduction

Public-Private Partnership (PPP) is broadly defined, by [1], as “a cooperative arrangement between the public and private sectors that involves the sharing of resources, risks, responsibilities, and rewards with others for the achievement of joint objectives” (p. 52). The growth of PPP projects in tourism in the last two decades is attributed to the many opportunities it provides to tourism destinations. For instance, reduction of risks and costs; acquiring capabilities and knowledge; spreading the scope of operational activities to reach international markets; creation of services and products; improving quality and efficiency of local services [2,3]. However, benefiting from the potentials of PPPs is hindered by many challenges that eventually led to the reported high rate of failure across the world [4,5,6,7]. Generally, stakeholders’ attitude has long been recognized as the primary determinant of partnership projects success or failure [8,9,10]. Researchers suggested different classifications to attitudes that help to arrange stakeholders according to potentials to cooperate or threaten the survival of partnership projects [11,12]. For example, [9] proposed a model with five levels of positions: active support, passive support, noncommittal, passive opposition, and active opposition. Reference [8] argued that these attitudes towards PPP need to be considered when determining the influence of each stakeholder on the strategies of decision-making and processes took. In tourism, PPPs work in a complex environment that creates multiple national and international stakeholders with different and sometimes conflicting interests and concerns. It is thus significantly important, yet complicated, to manage these various stakeholders, arrange relationships [3,13], seek their support [6], and instantaneously prepare for possible opposition [14].

Researchers reported that mismanaging opposition was the main failure factor in many PPP projects [15,16,17], particularly those in less developed countries [14]. Even though limited research and only in partnership and infrastructure fields have dedicated to understanding opposition (drivers and consequences) either in developed or developing countries, while none of the tourism studies has discussed the subject. Therefore, this study seeks to contribute to research by empirically explore antecedents of stakeholder opposition and provide practical guidelines to help tourism managers avoiding active opposition and project failure.

2. Literature Review

Some previous research attempted to identify possible reasons for stakeholder resistance to PPP projects. Reference [15], for instance, pointed out three leading causes which are primarily linked to poor stakeholder management. These are lack of stakeholder awareness about the concept of PPP [18]; insufficient education about the project [19], in addition to the lack of PPP management transparency about the project’s detailed information.

Also, the authors of [20,21] indicated that trust and commitment are central dimensions in any successful long-term cooperation and would lead stakeholders to show resistant behaviour towards a project. Reference [22] added that mutual commitment could not exist among stakeholders without a reasonable level of trust and good social interaction. For instance, [23] studied the possible resistance factors in the field of information system projects and found evidence that if stakeholders do not perceive the top management as supportive and committed to fulfilling a previously agreed obligation, stakeholders will show a resistant behaviour which significantly determines project failure.

Reference [24], on the other hand, asserted that active management support may be ineffective if the project is not perceived as well-administered. He added, “the primary emphasis of management’s commitment to the project must be shown in the efficiency and flexibility of its response to stakeholder needs” (p. 121). In the same vein, [25] studied project management success factors in developing countries and asserted that lack of communication and coordination with external stakeholders; lack of management support and commitment; bureaucracy in government; and lack of experienced managers are major factors that militate against the success of projects.

Researchers, also, noted that considering the interest of external stakeholders [23] and engaging them [26], particularly at the early planning phase of the project, should minimize any possible resistance; otherwise, the opposition may rise and cause PPP failure [27,28]. In line with the same notion, [16] studied public opposition in PPP projects and emphasized the importance of employing adequate strategies and processes to manage the influential external stakeholders; this is to avoid resistance, encourage stakeholder’s support and ultimately realize a successful PPP.

However, according to [29], a dominant group of public organization executives, private consultants, and researchers have taken a narrow perspective when dealing with stakeholders. As elaborated by [29] the external stakeholders in PPP projects were often marginalized in the planning and implementation phases. This has negatively affected the properness of objectives and operational outcomes of partnerships, thus significantly contributed to PPP projects’ failure. Likewise, the authors of [4,30] noted that previous research results on the opposition are derived from partners’ perspectives (internal stakeholders) and that views of the external stakeholders are primarily ignored., It is crucial to explore perspectives of the principal external players to build a holistic view on what they consider essential for their support and why they resist the implementation of a particular PPP project. Therefore, [4] examined the perspectives of external stakeholders in PPP road transportation projects and identified five critical factors to PPP success. These are knowledge of PPP, project location; timing of stakeholder engagement; transparency of internal stakeholders; and relationship with the internal stakeholders.

Mainly, our knowledge about the opposition of stakeholders is derived from construction [15,16] and infrastructure [27,31] literatures. In these fields, researchers focused on the public as the principles of external stakeholders. In tourism PPPs, the multiple national and international external stakeholders (e.g., tourists, local tourism providers or tourism federations) could have different characteristics, requirements, and expectations. Therefore, transferring prior knowledge of stakeholder opposition from other disciplines need to be carefully considered. Also, despite its importance in understanding tourism PPP implementation challenges, the literature on tourism does not offer enough cases of PPP project failure or success in either developed or developing countries.

Against this backdrop and for filling a gap in PPP and tourism research, this study explores antecedents of stakeholder opposition. This is by investigating a PPP e-tourism experience that has been failed due to stakeholder opposition in Egypt (the Egyptian Destination Management system (DMS)). A triangulation approach of stakeholder perspectives, methods of data collection, and data analysis has employed for a more holistic understanding of the subject. In the following, the research design is introduced. Then, findings of the qualitative and quantitative phases are discussed, and implications for theory and practice are presented.

3. Research Design

A mixed-methods approach is employed to investigate the active opposition of internal and external stakeholders in tourism PPP projects. This is to bring in more in-depth understanding (qualitative) while generalizing and validated outcomes (quantitative) [30]. Based on the approaches of [32,33,34,35] an exploratory-sequential design is used. First, given the dearth of knowledge about opposition in tourism PPP, a qualitative study is conducted to understand the subject and identify possible drivers to stakeholder opposition. The evidence is derived from the Egyptian DMS experience. It is a tourism PPP that failed due to opposition. Second, a quantitative inquiry was conducted to statistically test and validate the proposed scale of PPP opposition and generalize the findings to the Egyptian tourism context. The survey, then, was distributed to a panel of 488 experts as described in phase 2 of this study.

4. The Case Description

The Egyptian DMS was a tourism PPP project that was working between 1996 and 2008. The project was a partnership between the Tourism Ministry of Egypt as the public authority and a private IT company named Intercity Oz. The Egyptian DMS aimed at supporting the Egyptian tourism and hospitality business, particularly small and medium enterprises. This is to better compete in the e-market of tourism by providing destination-related information, training programs, and advertising opportunities [36,37]. The role of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism was to organize the PPP activities and urge the local enterprises to become members of the project. On the other hand, Intercity Oz, Inc. agreed to technically manage the DMS website and online forums. Although the Egyptian DMS was regarded as a successful PPP project in the first few years of its launch, it had completely failed in the end due to stakeholder opposition. The Egyptian DMS suffer from severe opposition from some of the local entities, which raised intense conflict among stakeholders. As a result, the Tourism Ministry decided to abandon the project and rejected further offer from local and international private companies to develop DMS jointly. Perspectives of internal and external stakeholders are explored to identify drivers of opposition to the Egyptian DMS projects.

5. Phase 1: Antecedents of Opposition—Developing the Scale

5.1. Sample and Analysis

Purposeful snowball sampling is chosen to identify participants who can provide rich information [38]. All interviewees were employees or members of the PPP project or witnessed its collapse. Semi-structure interviews with 22 participants from internal and external stakeholder groups are conducted as follows: the public sector (4); the private partner’s company (2); the Egyptian Travel Agents Association (ETAA) (2); Hotels (5), local travel companies (2 participants from large companies and seven from SME).

The qualitative data were interpreted based on the thematic analysis approach of Ref. [39]. Initial ideas about data interpretation were noted during the fieldwork, and analysis was conducted immediately after reaching the saturation point [40,41]. Data was read several times to attain familiarization with emergent patterns while reading through [42]. Codes were noted and further collated under initial themes. Themes and underpinning codes were then, checked against each other and back across the entire data set. After several analysis iterations and further refinement of codes and themes [39], a scale of 24 codes under six themes was identified as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Determinants of stakeholder opposition in tourism PPP projects.

5.2. Results of the Qualitative Phase

5.2.1. Capabilities of Stakeholders

Participants attributed the resistance of some local stakeholder groups to the DMS project to: (1) the lack of appropriate e-business knowledge of some external stakeholders and (2) the inappropriate managerial skills and experience of internal stakeholders to operate such a complex PPP project. An employee of the e-marketing department (the Ministry of Tourism) conveyed that, ”At that time [before 2009] the environment was not beneficial for developing DMS. We [the Ministry of Tourism] did not have that professionality in the electronic business”. Also, the owner of the private partner company added that, at the beginning of the DMS project, “the Minister had been aware enough to acknowledge the idea […] after the Minister was altered, it was not a friendly environment, new management was not convinced with the importance of developing DMS in Egypt”. Participants believe that the inappropriate e-business knowledge of public sector managers was one of the reasons that drive the decision of abandoning the Egyptian DMS/PPP and the later on opposition to develop any new DMS/PPP project in Egypt.

On the other hand, it was noted that small hotels and travel companies did not participate in the active opposition towards the DMS in Egypt. Although they are described as lacking the needed managerial and technical capabilities, the majority of them were motivated by the small tourism market-share to support the implementation of the Egyptian DMS.

5.2.2. Lack of Perceived Value

The case study revealed that lacking fair values and benefits as perceived by each stakeholder’s group had a significant share in motivating stakeholder opposition towards the DMS project. An employee in the marketing department at the Tourism Ministry held that ‘the Ministry would not have taken this decision [the termination of the project] if the senior managers witnessed obvious enhancement in the tourism market or destination image, the headaches and conflicts the project raised were much higher than the benefits possessed’. Also, participants asserted that opposing the Egyptian DMS was primarily led by a few large travel companies and the ETAA. The private company’s owner explained that the number of booking generated did not meet the expectations of the large hotels and travel companies. However, many of the smaller travel companies were satisfied with the value and benefits perceived, such as e-tourism knowledge acquisition and the number of online bookings.

5.2.3. Past Experience’s Outcomes

The results revealed that the failed experience of DMS in Egypt was the main reason for the resistance of the Tourism Ministry to participate in further DMS project. The manager of the marketing department of the Tourism Ministry disclosed that since the failure of the Egyptian DMS, the Ministry of Tourism had received many offers from national (e.g., Intoegypt company) and international (e.g., TIScover) private companies to develop DMS project. However, all offers -as mentioned by the marketing manager of the Tourism Ministry—faced resistance from both the Tourism Ministry and from the Egyptian Travel Agents Association (ETAA). Participants from the marketing department attributed such attitude to the fear of repeating a similar unsuccessful past project.

5.2.4. Absent of a Conflict (and Power) Management Mechanism

The results of this study have also evident that mismanagement of stakeholders’ conflicting interests, in addition to lacking an appropriate problem-solving mechanism would elevate conflict relations, motivate active opposition, and give clear opportunities to the domination of influential stakeholders, e.g., influence decisions against the desire of less-powerful stakeholders. The experience of the Egyptian DMS showed that a conflict between the private partner and some local tourism providers because of a disagreement on the management of tourists’ reviews and the online project forums. Based on the views of the participants, this conflict could have been managed if partners agreed on an approach -the beginning of the project- that would manage conflict and control the influence of influential stakeholders.

However, the problem took a severe form when the disagreed tourism providers ally with the Egyptian Travel Agents Association (ETAA) and other powerful local stakeholders to led opposition to the operation of the project. As a result, relationships got soured between the public and private partners. A few years before the complete failure of the Egyptian DMS, the Tourism Ministry (the public partner) decided to refer the case to a panel of judges and eventually abandon the project. Interviewees asserted that the ending of the DMS/PPP project was against the desire of many local small and medium tourism providers who felt a value-added to their business during the membership of the project.

5.2.5. Lacking an Appropriate Approach to Stakeholder Management

Findings of the exploratory study suggested that lacking a mechanism for significant interaction between internal stakeholders in addition to deficiencies in communicating and engaging external stakeholders driven the active opposition towards the Egyptian DMS project. Managing external stakeholder relationship was a joint responsibility between the public and private partner in the Egyptian DMS project. Nonetheless, the owner of the private company revealed that partners themselves had not had an effective communication mechanism, he said, “the judges suggested that these complaints should be forward to the Tourism Ministry. This is something that we tried to do many times, to no avail, we could have tried more if we could get contact info for just where we should have sent them”. Also, external stakeholders stated that although the partners have met representatives of local tourism providers at the early stage of the project development to discuss its implementation, this was not enough from their perspectives. An owner of a travel company articulated, “they [the DMS partners] met us in the Ministry of Tourism to introduce the project and promised they would train our employees; they only provide a couple of sessions. But as you know, effective training would require more”. Other participants of the local companies asserted that they did not do regular meeting to be able to express their views even when relations with the DMS management got complicated.

5.2.6. Limited Relational Strength: Trust and Commitment

The experience of the Egyptian DMS project revealed that the weak inter-organizational relationship among internal and external stakeholders was one of the reasons that led to opposition towards the tourism PPP project. When participants described the relationship of stakeholders, they referred to lacking aspects such as trust, friendly environment, management support, and commitment. For instance, an employee of the department of e-marketing, the Tourism Ministry, stated “[…]as you know, the Minister at that time was the owner of a travel company. I do not mean to refer to that he was corrupted, but I remember many local companies doubt his decisions to backing them. I believe more efforts should have been made to gain trust at that time”. Besides, a marketing manager in the Ministry of Tourism expresses his views in a way that implies a lack of trust in the private partner; she articulated that “[...]we faced many problems when we participated in the DMS. […] the Tourism Ministry had to protect its name, we should not have collaborated with a partner that serve his benefits, or in a project, we could not guarantee its results […]”. Also, doubts that partners were not working somewhat for the benefits of each other’s and other external stakeholders had resulted in a reluctance of some local tourism providers to commit to sharing important information with the Ministry. For instance, a hotel manager expressed, “Say if the Ministry of Tourism needs to update a specific occupancy rate, hotels would question why the Ministry need to know. They may think this to calculate their insurance, taxes, etc. [this is how he believes hotels might think] […]. There was a lack of trust […]”.

The experience of DMS in Egypt provides evidence that the absence of adequate trust had led stakeholders to treat each other with suspicion, which undermined their support and commitment. As a result, such a weak inter-organizational relationship decreases the willingness of some stakeholders to maintain the relationship and drive others to actively oppose the project.

6. Phase 2: Validating the Suggested Scale—Quantitative Survey

6.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedures

A total of 500 self-administrated questionnaires were distributed using a drop and collect approach to improving the response rate [43]. Respondents were selected in this research via a personal network. The research team are employed in Tourism and Hotels Management college in Egypt. Therefore, they have a good network with the targeted sample (travel agents, hotels, public sectors, and academics). A total of 488 valid responses were collected as follows:

Employees and middle managers (164) in the government sector who are currently working or previously worked in PPP related projects (the Ministry of Tourism (36), the Egyptian Tourism Federation (ETF) (29), the Tourism Promotion Authority (28), the Tourism Development Authority (38) and The Egyptian public-private partnership Central Unit (33) at the Ministry of Finance).

Industry practitioners (259) including hotels (113) and travel companies (146).

Academic scholars (65) who have conducted relevant research on the partnership, PPP and DMS projects.

6.2. Data Analysis Techniques

The responses characteristics are shown in Table 2, and some descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtoses) are presented in Table 3. A three-stage consequence data analysis technique was employed to validate the developed scale of this study to measure stakeholder perceptions about the antecedents of opposition in tourism PPP Projects. First, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) method was conducted for detecting the dimensions and their related items and subsequently [44]. Second, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was analyzed for validating convergent and discriminate properties of the developed factors [45]. Finally, the relative importance index (RII) analysis was conducted to rank the dimensions of stakeholder opposition according to their relative importance.

Table 2.

The profile of respondents.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

6.3. Results of the Quantitative Phase

6.3.1. Responses Profile and Descriptive Analysis

The respondent’s majority were males (65%) (Table 2), which indicates that the tourism industry in Egypt is dominated by a male over female. Most of them were also aged between 30 and 60 years old (95%). The majority of them were also well educated as the university graduates represent 65% and 25 are postgraduate. Respondents who are working in public sectors (33%) are higher than those working in travel agents (30%) and hotels (23%), while the expert academics represent 13.5% of the total responses (see Table 2).

Table 3 shows some descriptive statistics. The questionnaire maximum and minimum scores of answers were 5 and 1 correspondingly [1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree]. The calculated mean (M) values for all items were ranged between 3.82 and 4.26, the estimated standard deviation (SD) scored were between 1.198 and 0.763 (Table 3), which gives evidence that the data are spread further and concentrated less near the mean value [46]. Furthermore, the values for skewness and kurtosis showed in Table 3 are less than the cut-off value of −2 and +2 as suggested by Ref. [47], which indicate normal univariate distribution and further approve that the data do not violate the normality assumptions [48].

6.3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The 24 variables measuring the six dimensions (inadequate capabilities, lack of perceived value, poor past experience’s outcomes, absence of a conflict management mechanism, lacking stakeholder management approach, and limited relational strength) that were developed to measure the stakeholder perceptions about the antecedents of stakeholder opposition in tourism PPP Projects were subjected to EFA in SPSS vs. 20 for data summarizing and reduction. This paper used the principal component technique for factor extraction and varimax orthogonal rotation to attain the best solution.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity shows an approximate Chi-square of 18,676.050, with 267 df and significance 0.000, which reflects the existence of non-zero correlation among the 22 items that measure the predetermined dimensions and a high degree of homogeneity among variables [46].

The overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy is 0.81, which is higher than the recommended cut-off points of 0.5 [49,50]. Overall, this information satisfies the fundamental requirements for factor analysis [49]. The exploratory factor analysis generated a six-factor solution. A six-factor structure is suggested using the criterion of an eigenvalue greater than 1, and the extracted factors account for 85.14% of the total variance.

Two items were dropped (one variable from lack of perceived value dimension (i.e., perceived threats to interest) and one from lacking stakeholder management approach dimension (i.e., inefficient training programs on the significant adoption of the PPP project)) due to factor loading (FL) less than 0.4.

Factor loadings for all other variables were all higher than 0.6 on their own factors, as recommended by [50]. The factor loadings for inadequate capabilities are ranged from 0.759 and 0.894, FL for lack of perceived value is ranged from 0.819 and 0.911, FL for poor past experience’s outcomes are ranged from 0.847 and 0.902, FL for the absence of a conflict management mechanism are ranged from 0.825 and 0.890, FL for lacking stakeholder management approach are ranged from 0.760 and 0.809, and FL for limited relational strength are ranged from 0.774 and 0.89 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis results.

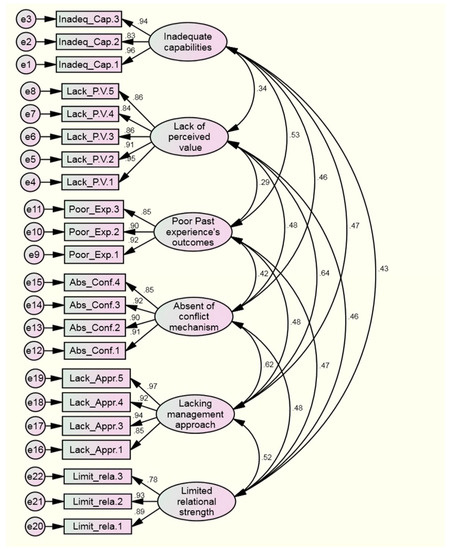

6.3.3. First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

A total of 22-items first-order structured CFA employing the maximum likelihood estimation method was conducted to assess convergent and discriminant validity of the developed scale (see Figure 1). The CFA items consist of three items from inadequate capabilities, five items from lack of perceived value, three items from poor past experience’s outcomes, four items from absent of conflict mechanism, four items from lacking management approach, and three items from limited relational strength. The CFA results of the measurement model displayed a good fit to data: χ2 = 668.136 (df = 194), p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.444, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.966, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.035, with SRMR value of 0.039 (see Table 5).

Figure 1.

First-order CFA (Amos output).

Table 5.

Convergent and discriminant validity.

Results in Table 5 also display the Cronbach’s alpha (a) scores for all dimensions and composite reliability (CR) values. The values of Cronbach’s alpha (a) are located between 0.89 and 0.94; these results are more than the threshold value of 0.70 as argued by Ref. [51], which approve the internal consistency of the developed scale.

CR results are ranged between 0.90 and 0.958 and are above the recommended cut-off point of 0.70 [50] (see Table 5), which further supports the reliability of the developed measures.

Convergent validity is estimated by two main conditions suggested by [52] all FL to its predetermined developed dimensions should exceed 0.70, and (2) the average variance extracted (AVE) data of all predeveloped dimensions should be above 0.50. Table 5 displays that all FL are between 0.781 to 0.975 and are above the recommended value of 0.70. Similarly, the AVE data for all dimensions are ranging from 0.77 to 0.87 and are above the suggested value of 0.50.

Overall, the previous results confirm that the measures of the six dimensions of the stakeholders’ perceptions about the antecedents of stakeholder opposition in tourism PPP (inadequate capabilities, lack of perceived value, poor past experience outcomes, absence of a conflict management mechanism, lacking stakeholder management approach, and limited relational strength) that previously devolved in the qualitative phase are in reality related. Likewise, discriminant validity is estimated in this paper by two conditions recommended by [50,52,53] the inter-correlations scores for each dimension (below diagonal value) should not be more than the square root of AVE scores for each dimension (bold-diagonal) as displayed in Table 5) the AVE scores of each dimension should be greater than the maximum shared value (MSV) as shown in Table 5. The previous results support the discriminant validity of the predeveloped scale in this study. For example, in evaluating discriminant validity between inadequate capabilities and lack of perceived value, the average variance extracted of inadequate capabilities is 0.828, which is greater than the maximum shared variance, which is 0.278 (see Table 5). Additionally, the Square root of the AVE of inadequate capabilities is 0.923 (bold-diagonal) exceeds the intercorrelations between all other dimensions (below bold-diagonal). This approves the discriminant validly. In other words, this gives evidence that each predeveloped dimension shares more variance with its predetermined variables than it shares with other dimensions.

6.4. Relative Importance Index Analysis (RII)

Relative importance index analysis was conducted in this study to rank the six dimensions that were developed and validated to measure stakeholder perceptions about the antecedents of opposition in tourism PPP Projects, according to their relative importance (see Table 6).

Table 6.

The Ranking Results of each Variable and Dimensions.

The following equation is employed to identify the relative importance index: RI = Σ (w)/A × N, where w is the weighting as allocated by each participant on a scale between 1 to 5, with 1 indicating the least and 5 the highest. A is the highest weight value, and N is the total number of participants. According to Ref. [54] suggestions, five main important categories are interpreted from RI scores: high (H) (0.8 ≤ RI ≤ 1), high medium (H−M) (0.6 ≤ RI ≤ 0.8), medium (M) (0.4 ≤ RI ≤ 0.6), medium-low (M−L) (0.2 ≤ RI ≤ 0.4) and low (L) (0 ≤ RI ≤ 0.2).

The data displayed in Table 6 indicated that the highest overall ranked items that cause the stakeholder opposition in PPP Projects are related to lack of perceived values dimension (i.e., small returns or gains, few bookings, costs exceed benefits and low e-marketing knowledge) followed by items illustrating limited relational strength dimension (i.e., not enough support and commitment from top management, mistrust, and unfriendly environment). Inadequate capabilities of stakeholders was ranked number three in its importance of the stakeholder opposition in tourism PPP (i.e., lacking DMS/PPP experience of partners, and limited technical knowledge and managerial skills of internal and external partners), while poor past experience outcomes related items generated the fourth reasons (rank) in the stakeholder opposition in PPP Projects achieved (i.e., fear of repeating a similar unsuccessful past project, adverse outcomes of past projects, and previous failed partnerships), followed by lacking stakeholder management approach (i.e., gaps between expected value and real value obtained, neglecting interests and needs of stakeholders, and inadequate communication), and finally, absent of conflict management mechanism related items in the lowest importance index that may cause the stakeholder opposition in PPP projects (i.e., lacking a problem-solving mechanism, ignoring signs of conflict relations, and competing interests and complex relations) respectively.

7. Discussion

The qualitative phase of this study has generated a scale of six DMS/PPP opposition dimensions that was further statistically examined for their importance. These dimensions are lack of perceived values and benefits, limited relational strength, inadequate capabilities of stakeholders, poor experience outcomes, lacking stakeholder management approach, and absence of a conflict (and power) management mechanism (Table 1). Also, the findings of the qualitative and quantitative phases have proposed 22 related factors pointed to what could influence active opposition in each of the six dimensions (Table 4 and Table 5).

The results of the RII asserted that the highest overall ranked dimension identified by the internal and external stakeholders was the lack of satisfactory values and benefits. Calculations of stakeholders to costs and benefits, in terms of, e.g., e-marketing knowledge acquisition, destination image and the number of bookings generated, are deciding the actions they take to either support or oppose. This result complement previous studies, which showed that the actions of stakeholders are directed to protect their interests [28]. Stakeholders could resist the implementation of a specific project if the benefits they gained are low [16,22] or their business interests are threatened [12,37].

The findings also confirmed that limited relational strength between and within internal and external stakeholder groups (mistrust, lacking commitment and support and unfriendly environment) was the second dimension that drives opposition. In support of these findings, the authors of [20,22] indicated that trust and commitment are central dimensions in any successful long-term cooperation and would lead stakeholders to show resistant behaviour towards a project [24].

In addition, the findings revealed that lacking crucial technical knowledge and PPP expertise to effectively deal with and manage a tourism DMS/PPP project is one of the main factors that drive opposition. Lacking adequate managerial and technical capabilities would lead stakeholders to rationalize the importance of implementing PPP to the tourism industry and would also drive opposing attitudes and behaviours towards the inclusion of other stakeholders and the project as a whole. Similarly, Ref. [55] studied PPP in Nigeria and noted that lacking adequate knowledge and PPP experience led public authorities to accept responsibilities and risks beyond their capabilities. This has resulted in severe opposition among external stakeholders and obstructed the implementation of many PPP projects. These results thus confirm prior studies found that lacking awareness about the concept of PPP [15] and limited skills and knowledge [19] would hinder the building of good interrelationship between partners [18] and would thus lead to opposition.

Another important finding of this study is that perceptions about poor past DMS/PPP experiences would influence the public partner and external stakeholders to oppose implementing a new project in fear of repeating similar undesired outcomes. This finding complemented a study [23] that investigated stakeholder resistance in software projects and pointed out that adverse outcomes of past projects may affect stakeholder expectations and drive resistance to repeat an unsuccessful experience.

Moreover, the findings revealed deficiencies in communicating and engaging external stakeholders, mismanagement of relationships and conflicting interests, in addition to lacking an appropriate problem-solving/conflict mechanism that could elevate conflict relations and motivate active opposition. These findings supported by previous results [16,27,31] that opposition is determined by the lack of an effective approach for managing stakeholder relationships. It is thus imperative for tourism PPP success to employ a mechanism through which the PPP management can monitor the relationship between stakeholder groups, coordinate the conflicting interests [3,13], control the possible domination of power [37], and encourage cooperation [6,37]. This is to maintain a positive, productive relationship among stakeholder groups and avoid active opposition.

8. Conclusions and Implications

This study has utilized a qualitative-sequential mixed-method approach to explore antecedents of stakeholder opposition in tourism PPP projects by analyzing internal (partners) and external (e.g., tourism providers) stakeholder perspectives. The case of the Egyptian DMS gives a deep insight into the subject since it is a tourism PPP experience that was failed due to public sector abandonment of the project. Our contribution lies in the development of a measurement scale of antecedents of tourism PPP opposition. We believe that the current study possesses significant implications for theory and practice.

8.1. Implications for Theory

This is the first study to investigate opposition in tourism PPP projects. It contributes to knowledge in this subject area by deepening understanding of opposition and its antecedents in tourism PPP. A scale of six dimensions and 22 related factors is developed based on internal and external stakeholder perspectives. In addition, this study adds to the general studies of PPP as it investigated a tourism PPP experience that was failed due to opposition providing insights into the process through which the opposition and abandonment decision is taken and how external stakeholder dynamics may contribute to such a decision.

Moreover, by exploring the perspectives of tourism providers (travel companies and hotels) and other prominent players (local tourism federations) in the tourism business, this study addresses recent calls by researchers such as [4,30] to investigate the role of external tourism stakeholders in PPP opposition.

8.2. Implications for Practice

This study provides important insights on managing stakeholders in tourism PPP projects. It is important for managers to understand what drives active opposition and how to avoid it through the different stages of the project. This study identified six dimensions and related 22 factors of stakeholder opposition that complement each other and drive active opposition. The results suggested that PPP managers need to help the different stakeholders realizing the potentials of their cooperation while providing each of them with motivations for their commitment. This can be done by developing a practical stakeholder management approach and a conflict (and power) management mechanism to manage relations between and within stakeholder groups, including (1) suitable methods of communication and different activities to engaging stakeholders during various stages of the project (2) clarification of values and benefits at an early stage of PPP process, (3) a trust-building approach to build a robust and friendly relationship between internal and external stakeholders, and (4) building strong stakeholder capacity by providing sufficient education about the project and designing training programs to improve technical knowledge and managerial skills of the public sector as well as members of the local companies.

9. Limitations and Further Research

Future research could address the limitations of this study to improve understanding of opposition in tourism PPP. This study is limited by the choice of one tourism PPP type (DMS) and the single-country context (Egypt). Future research can extend our knowledge by investigating more contexts and other kinds of PPP in tourism to build on the results of this study to determine differences and similarities. Further studies could also employ a multigroup analysis technique [56,57,58] to validate the developed PPP opposition scale in a different context and compare the results. Also, the results of this study were derived from a cross-sectional design, while the understanding of PPP opposition would benefit from longitudinal research that examines the interrelationships between dimensions and related factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; methodology, I.A.E., M.S.A. and M.G.; software, I.A.E., A.M.S.A.; validation, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; formal analysis, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; investigation I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; resources, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.; data curation, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; visualization, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; project administration, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and M.G.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of “Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IFT20189).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Financing Committee (Project number IFT 20189, approval date 11 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kwak, Y.H.; Chih, Y.; Ibbs, C.W. Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Public Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Cooperation and Partnerships in Tourism: A Global Perspective; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Public–private collaboration in the tourism sector: Balancing legitimacy and effectiveness in local tourism partnerships. The Spanish case. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2012, 4, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, C.; Carrillo, P.; Tuuli, M. Stakeholder management in PPP projects: External stakeholders’ perspective. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gao, H.; Tao, H.; Xu, M. Does PPP Matter to Sustainable Tourism Development? An Analysis of the Spatial Effect of the Tourism PPP Policy in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroff, D.M.; Deason, G.G.; Seekamp, E.; Iyengar, J. Integrating frameworks for evaluating tourism partnerships: An exploration of success within the life cycle of a collaborative ecotourism development effort. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, S. Public-private partnerships for development: Governance promises and tensions. In The Emerald Handbook of PPPs in Developing and Emerging Economies. Perspectives on Public Policy, Entrepreneurship and Poverty; Leitao, J., Marais Sarmento, E., Aleluia, J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.-H. Stakeholders’ attributes, behaviours, and decision strategies in construction projects: Importance and correlations in practice. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, B.; Mills, C. Managing stakeholders. In Gower Handbook of Project Management, 3rd ed.; Turner, R.J., Sinister, S.J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2000; pp. 757–775. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J.; Havela, L.; Savage, G. Stakeholder Dynamics during the Project Front-End: The Case of Nuclear Waste Repository Projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, V.; Morin, P.-P. Project Leadership Influences Resistance to Change: The Case of the Canadian Public Service. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, F.; Jennifer, L. Public–private partnerships for nature-based tourist attractions: The failure of Seal Rocks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 942–956. [Google Scholar]

- Amadi, C.; Carrillo, P.; Tuuli, M. Stakeholder management in public-private partnership projects in Nigeria: Towards a research agenda. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual ARCOM Conference, Portsmouth, UK, 1–3 September 2014; pp. 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gohary, N.M.; Osman, H.; El-Diraby, T.E. Stakeholder management for public private partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henjewele, C.; Fewings, P.; Rwelamila, P. De-marginalizing the public in PPP projects through multi-stakeholder’s management. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2013, 18, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwangwu, G. Stakeholder Opposition Risk in Public-Private Partnerships. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Res. 2019, 5, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lau, E.; Rowlinson, S. The implications of trust in relationships in managing construction projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2011, 4, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Elshaer, I.; Shaker, A. The Successful Adoption of IS in the Tourism Public Sector: The Mediating Effect of Employees’ Trust. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.Y.B.; Ng, F.F. Enhancement of organizational commitment through propensity to trust. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2015, 22, 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Jusoh, R. A multidimensional view of intellectual capital: The impact on organizational performance. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 668–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovec, S.L.; Hovelja, T.; Vavpotič, D.; Krisper, M. Diagnosing organizational risks in software projects: Stakeholder resistance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marble, R.P. A system implementation study: Management commitment to project management. Inf. Manag. 2003, 41, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, D.F. Project Management Practices and Critical Success Factors—A Developing Country Perspective. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, p14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chung, D.; Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J. Toward the betterment of risk allocation: Investigating risk perceptions of Australian stakeholder groups to public-private partnership toll road projects. Res. Transp. Econ. 2010, 30, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hubbard, M.; Liao, C. When public-private partnerships fail: Analysing citizen engagement in public-private partnerships—Cases from Taiwan and China. Public Manag. Rev. 2012, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.T.; Wong, J.M.; Wong, K.K. A public private people partnerships (P4) process framework for infrastructure development in Hong Kong. Cities 2013, 31, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.I.; Moldoveanu, M. When will stakeholder groups act? An interest-and identity-based model of stakeholder group mobilization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwelamila, P.D.; Fewings, P.; Henjewele, C. Addressing the Missing Link in PPP Projects: What Constitutes the Public? J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Projects: What constitutes the public? J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 31, 1–9.

- Sariola, R.; Martinsuo, M. Enhancing the supplier’s non-contractual project relationships with designers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, C.; Carrillo, P.; Tuuli, M. PPP projects: Improvements in stakeholder management. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2019, 27, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed-Methods Research; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Canavan, B. Sustainable tourism: Development, decline and de-growth. Management issues from the Isle of Man. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Toddlers, tourism and Tobermoray: Destination marketing issues and television induced tourism. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Pearce, P.L. Host tourism aspirations as a point of departure for the sustainable livelihoods approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, P.; Frew, A. Destination Website Effectiveness: A Delphi-Based eMetric Approach; Conference Papers, No. 7; Dublin Institute of Technology: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. Destination Management Systems (DMS): A Reality Check in the Greek Tourism Industry. Inf. Commun. Technol. Tour. 2009, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Method, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P., Sher, K., Panter, A.T., Long, D., Rindskopf, D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.; Biklen, K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods; Pearson/Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeh, K.; Brock, J.K.-U.; Zhou, Y.J. The drop and collect survey among industrial populations: Theory and empirical evidence. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, R.A. paradigm for developing better measures for marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with IBM SPSS (21): A Guide For Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, M. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-60623-876-9. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publication: London, UK; Thousand Oaks: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 007047849X. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, P.O.; Olomolaiye, P.O. Development of sustainable assessment criteria for building materials selection. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2012, 19, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Akamavi, R.K. Competing models of quality management and financial performance improvement. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Augustyn, M.M. Testing the dimensionality of the quality management construct. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2016, 27, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).