A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy

Abstract

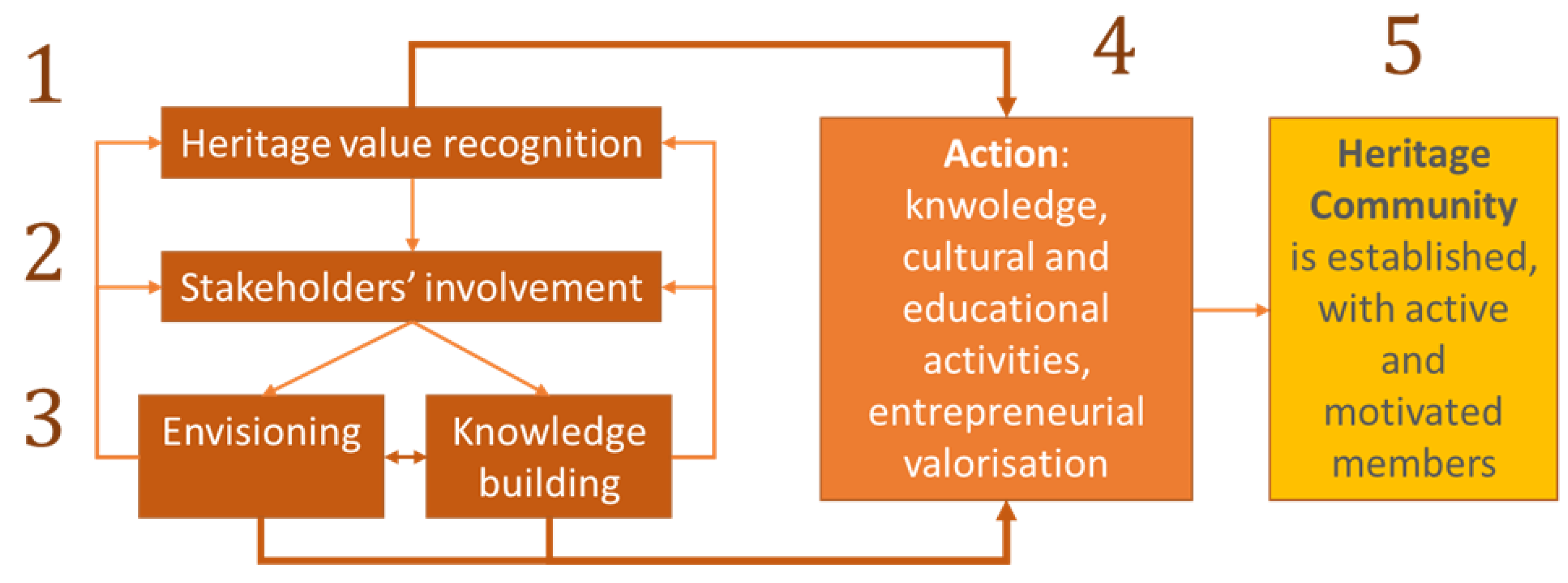

1. Introduction

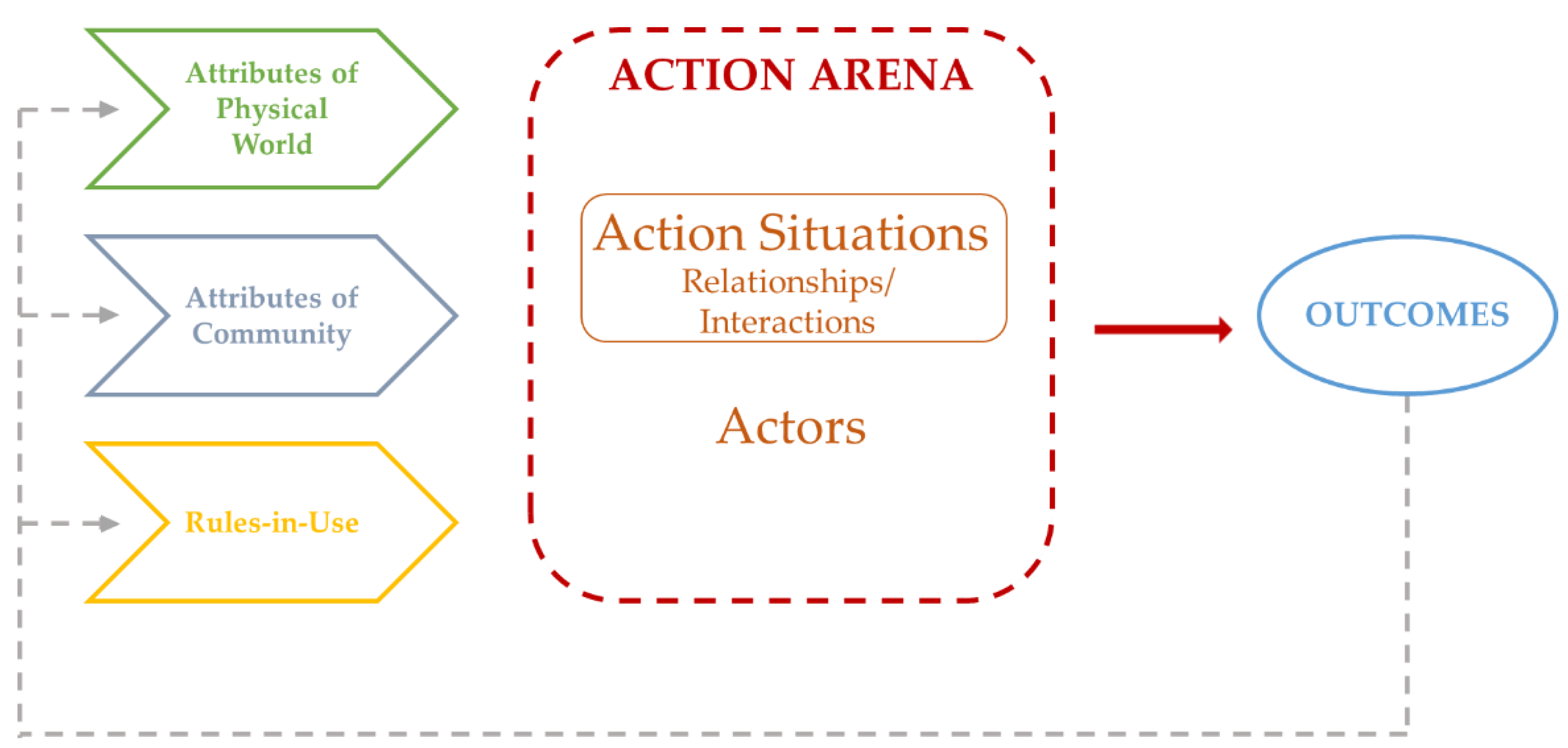

1.1. Cultural Heritage as Common Good

2. Materials and Methods

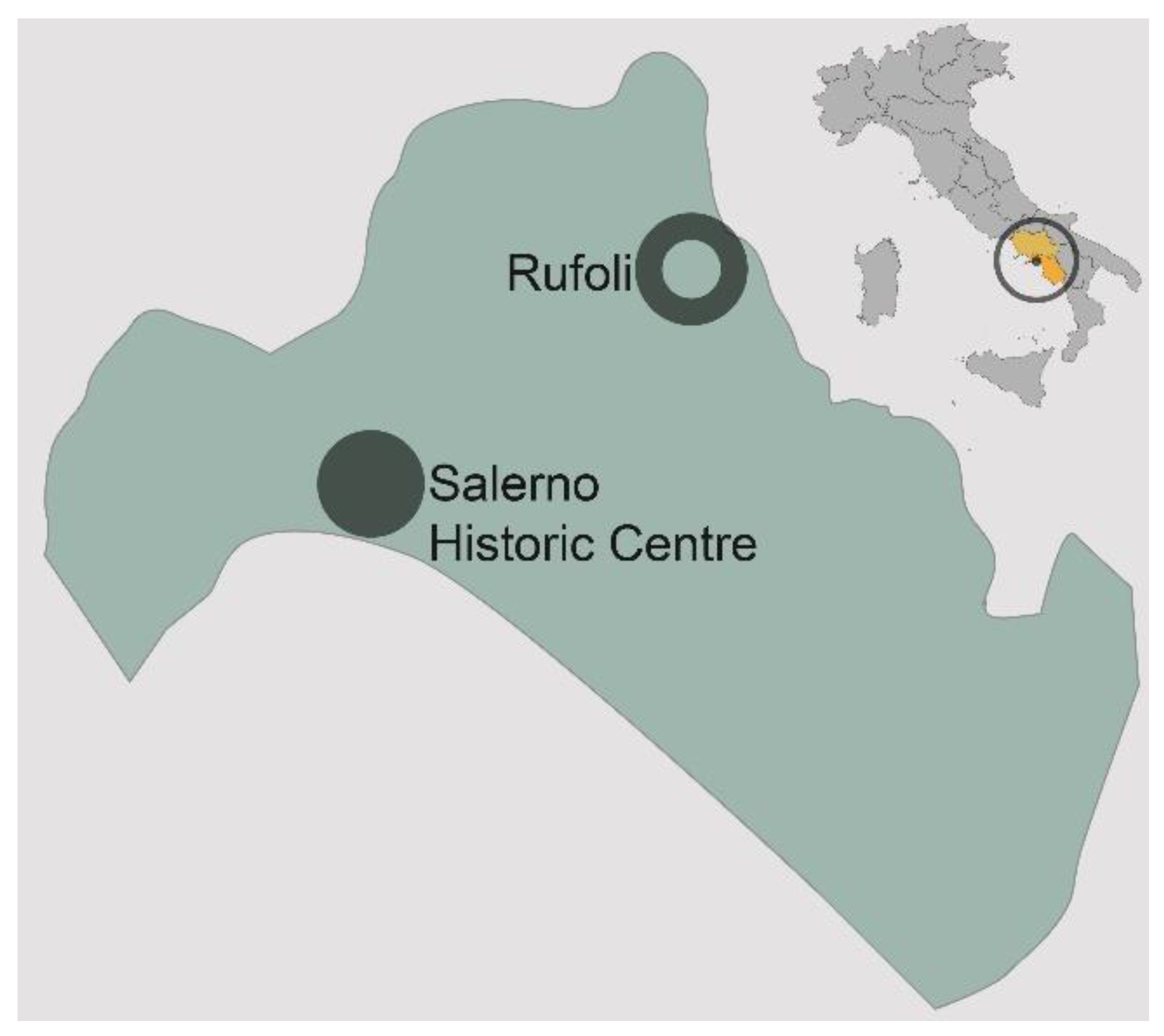

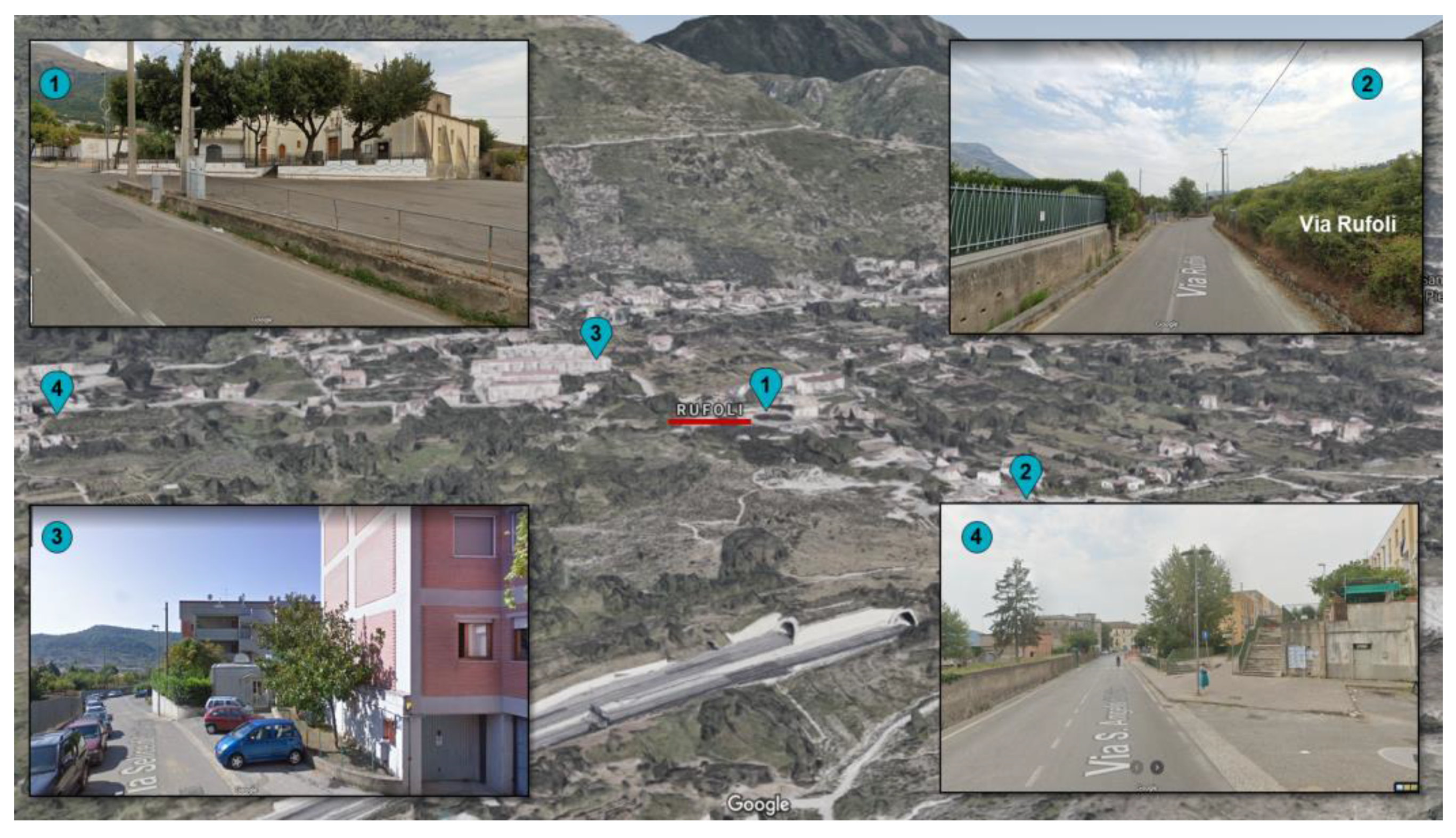

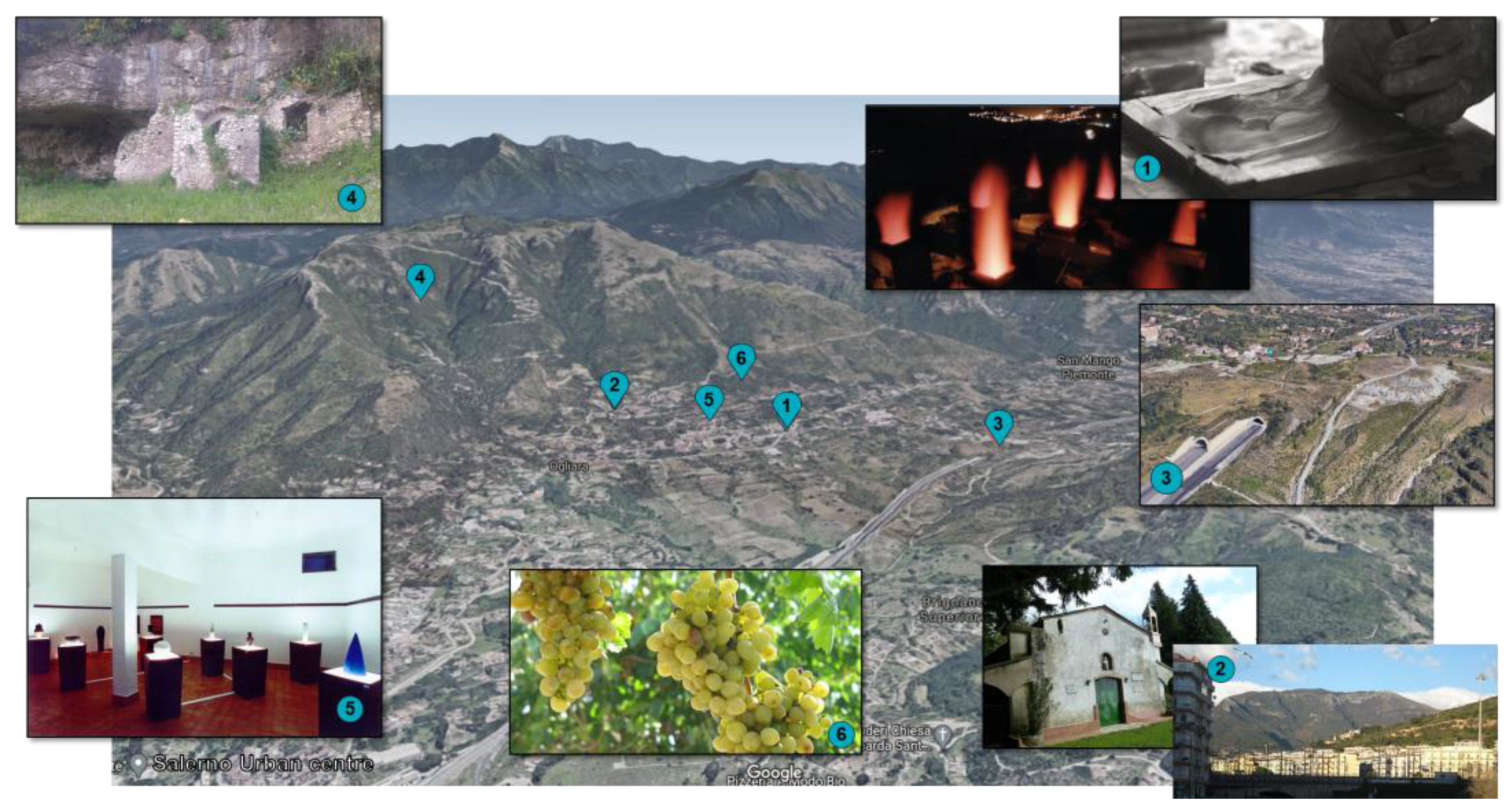

2.1. The Case Study of the Ancient Furnaces of “cotto” in Rufoli, Salerno

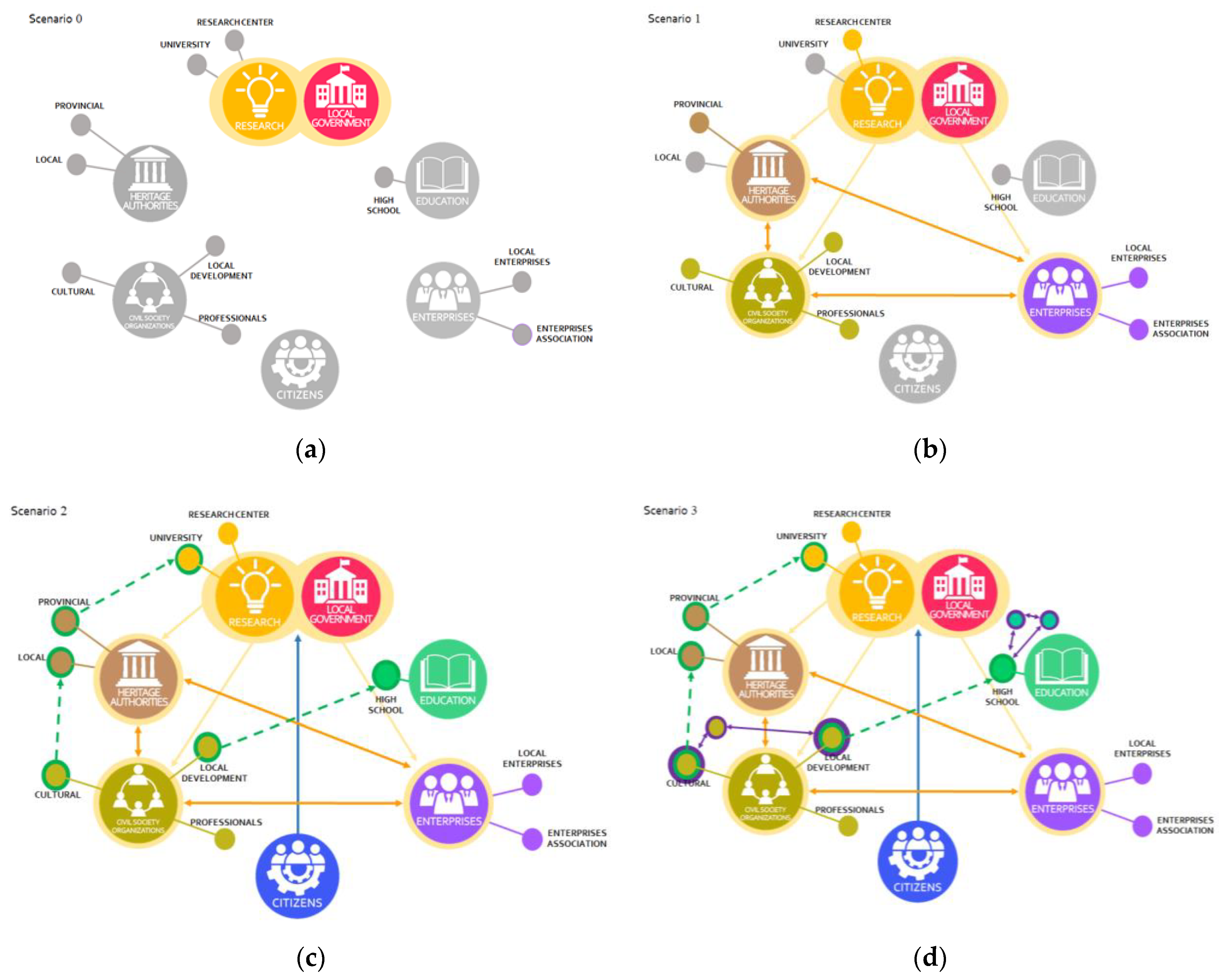

2.2. Stakeholders’ Involvement: Building a Heritage Community

- Clarify who are the project stakeholders.

- Understanding and aligning the expectations and individual impact that each stakeholder may have with the project objectives.

- Outlining the processes of changing requirements; knowing that their needs (i.e., needs and expectations) are likely to change.

- Linking needs and expectations with risk planning and risk response activities.

- Conscientiously plan the communication strategies of the project.

- Institutional factors: the set of rules or institutions that govern the arena.

- Socio-cultural and economic factors: characteristics of the individual appropriators and of the community of reference, both economic (e.g., the degree of dependence of the users on the resource itself) and individual and cultural (mutual trust, the existence of shared values, and so on).

- Physical factors: the environmental context, both natural and artificial, in which the actors move and against which their actions acquire a concrete meaning. The context interacts with the number of users and their capacity to consume the resource, determining the characteristics of exploitation [33].

2.3. Heritage Mapping and Analysis

2.4. Stakeholders’ Analysis and Engagement Process

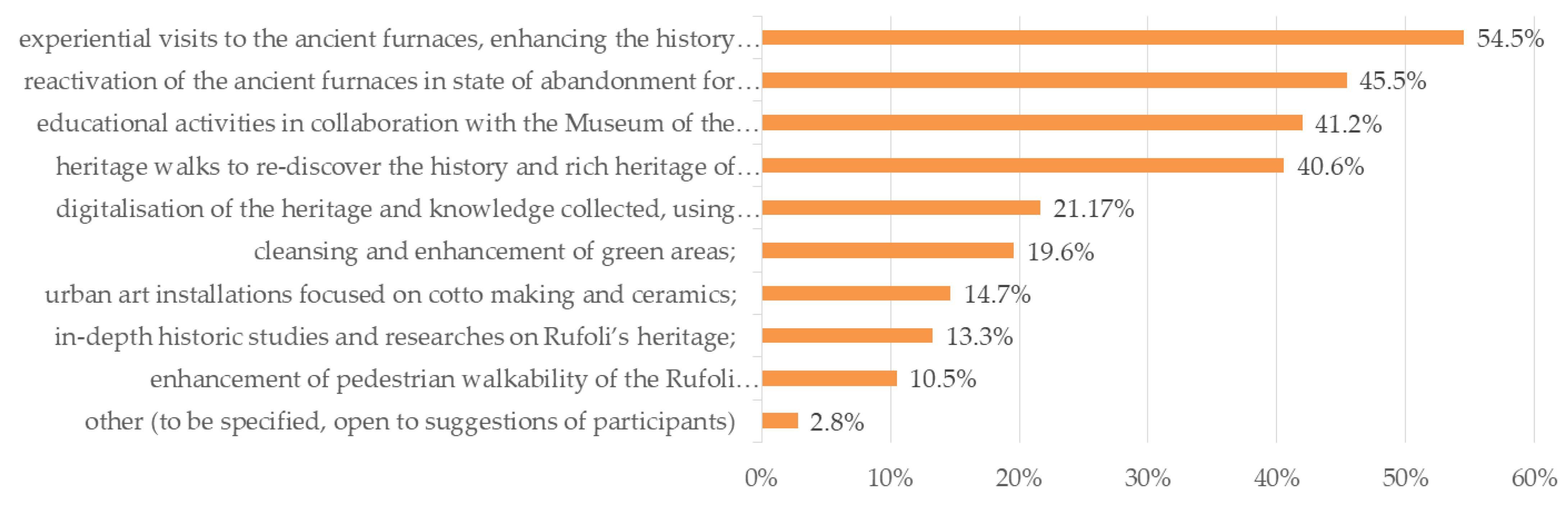

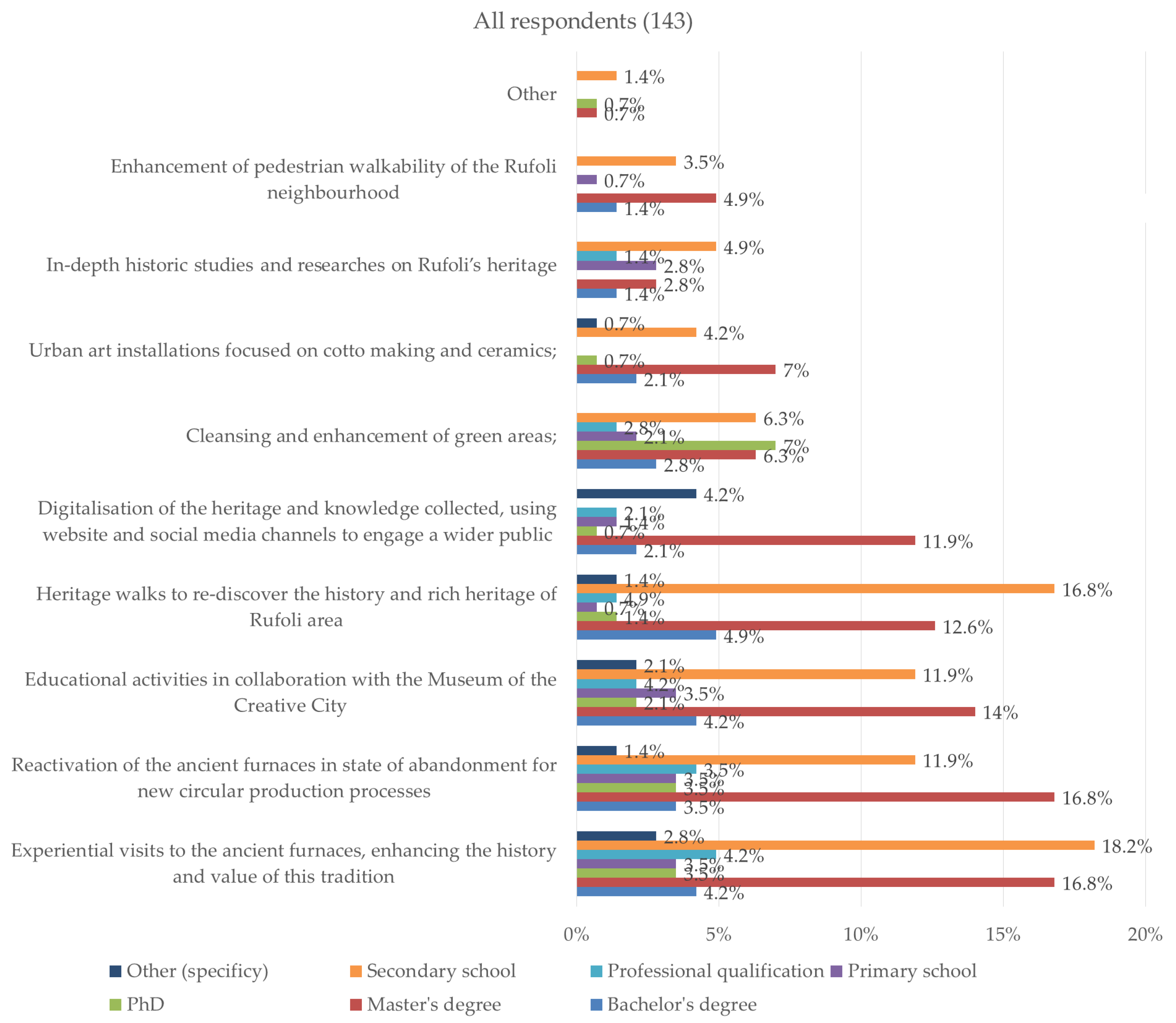

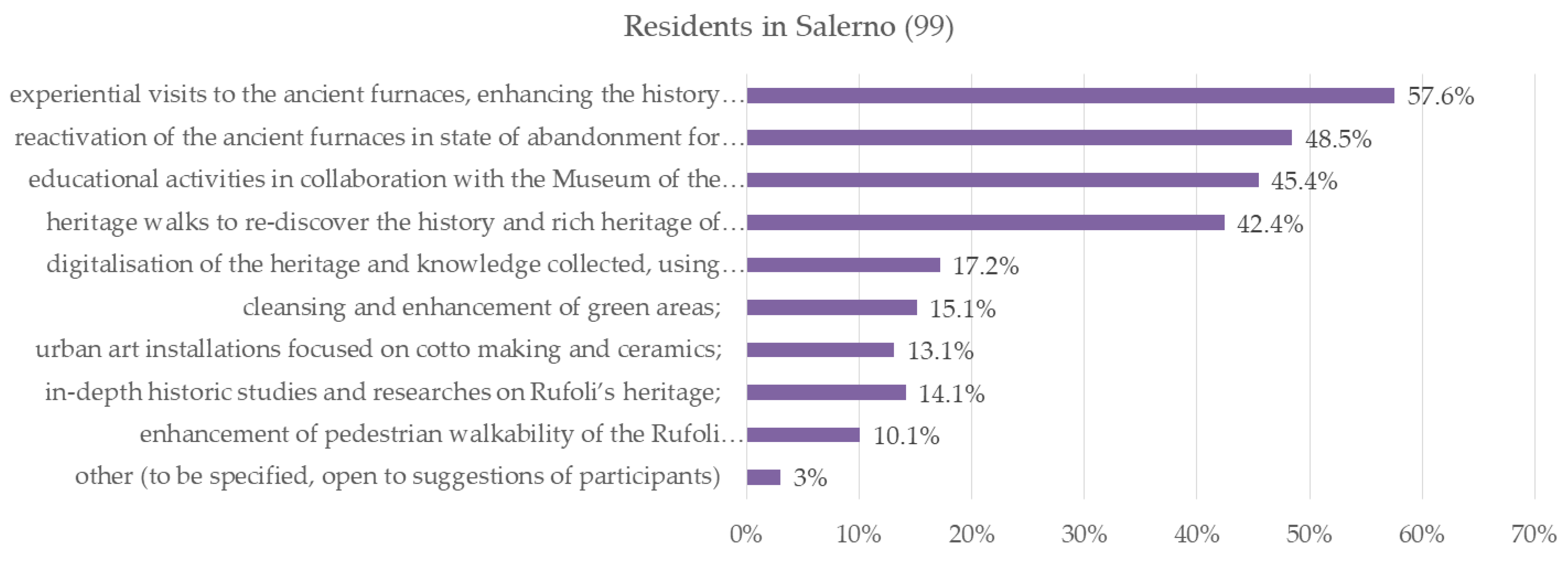

2.5. Towards a Shared Vision for Heritage Reuse and Regeneration: Results of the Envisioning Phase

- reactivation of the ancient furnaces in state of abandonment for new circular production processes;

- experiential visits to the ancient furnaces, enhancing the history and value of this tradition;

- heritage walks to re-discover the history and rich heritage of Rufoli area;

- digitalization of the heritage and knowledge collected, using website and social media channels to engage a wider public;

- in-depth historic studies and research on Rufoli’s heritage;

- urban art installations focused on cotto making and ceramics;

- educational activities in collaboration with the Museum of the Creative City;

- cleansing and enhancement of green areas;

- enhancement of pedestrian walkability of the Rufoli neighborhoods;

- other (to be specified, open to suggestions of participants).

2.6. Envisioning, Knowledge Building, Knowledge Sharing, and Awareness Raising

- Introduction/welcome page: brief presentation describing the context and the objectives of the questionnaire;

- Informed consent form (required to participate);

- Section 1—knowledge of the cotto tradition: assessment of the level of knowledge of the ancient furnaces of Rufoli and the cotto tradition;

- Section 2—significance of the tradition and the production of cotto for the community: assessment of citizens’ perception about the value of this cultural heritage in Rufoli and the importance perceived about its conservation and enhancement;

- Section 3—prioritization of actions: priorities assessment related to a set of suggested actions for the enhancement of cultural heritage in Rufoli; reflections and suggestions for the elaboration of development scenarios for the area of interest; willingness of citizens to be involved in workshops on extensive cultural heritage mapping;

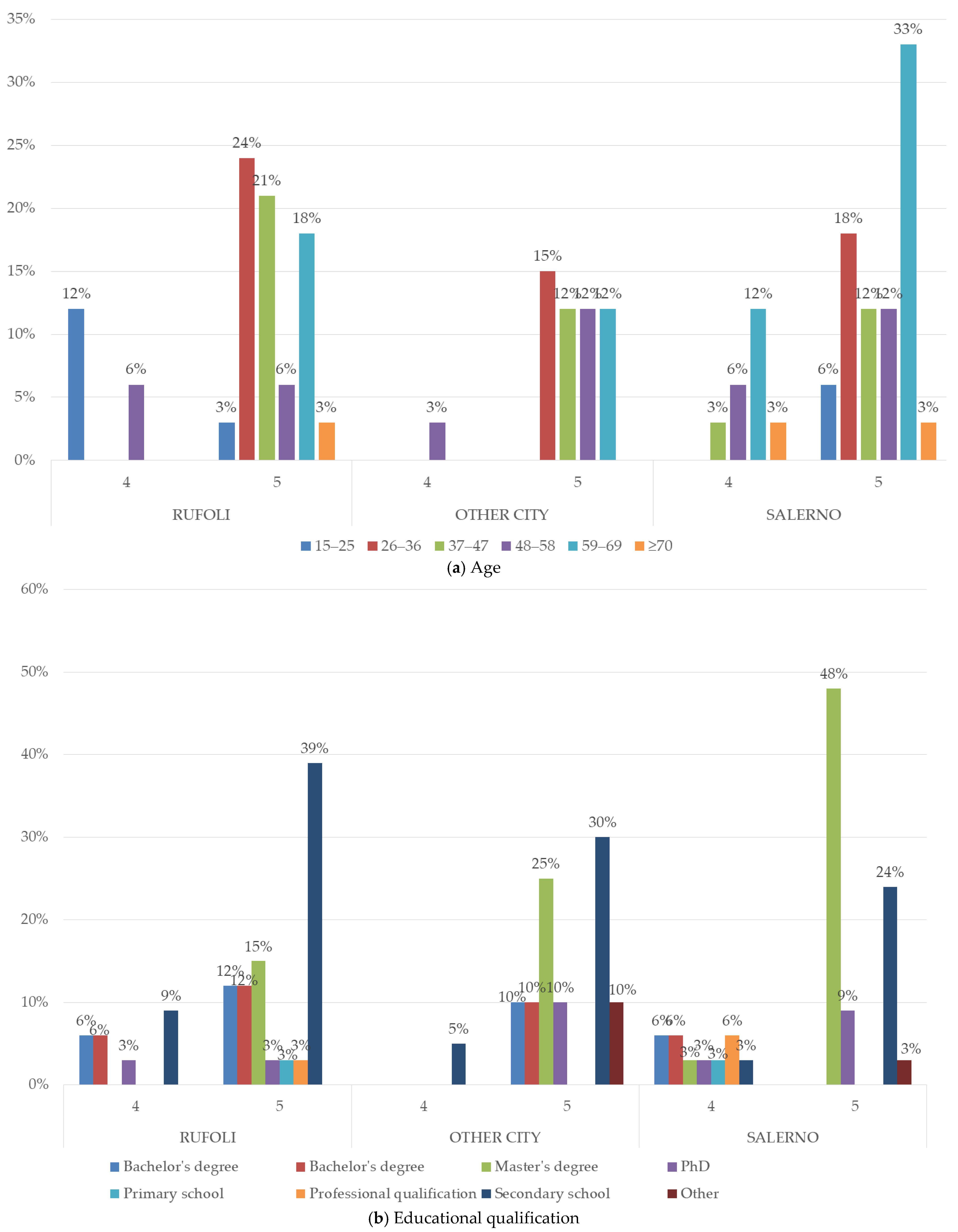

- Demographics: age, level of education, profession, place of residency.

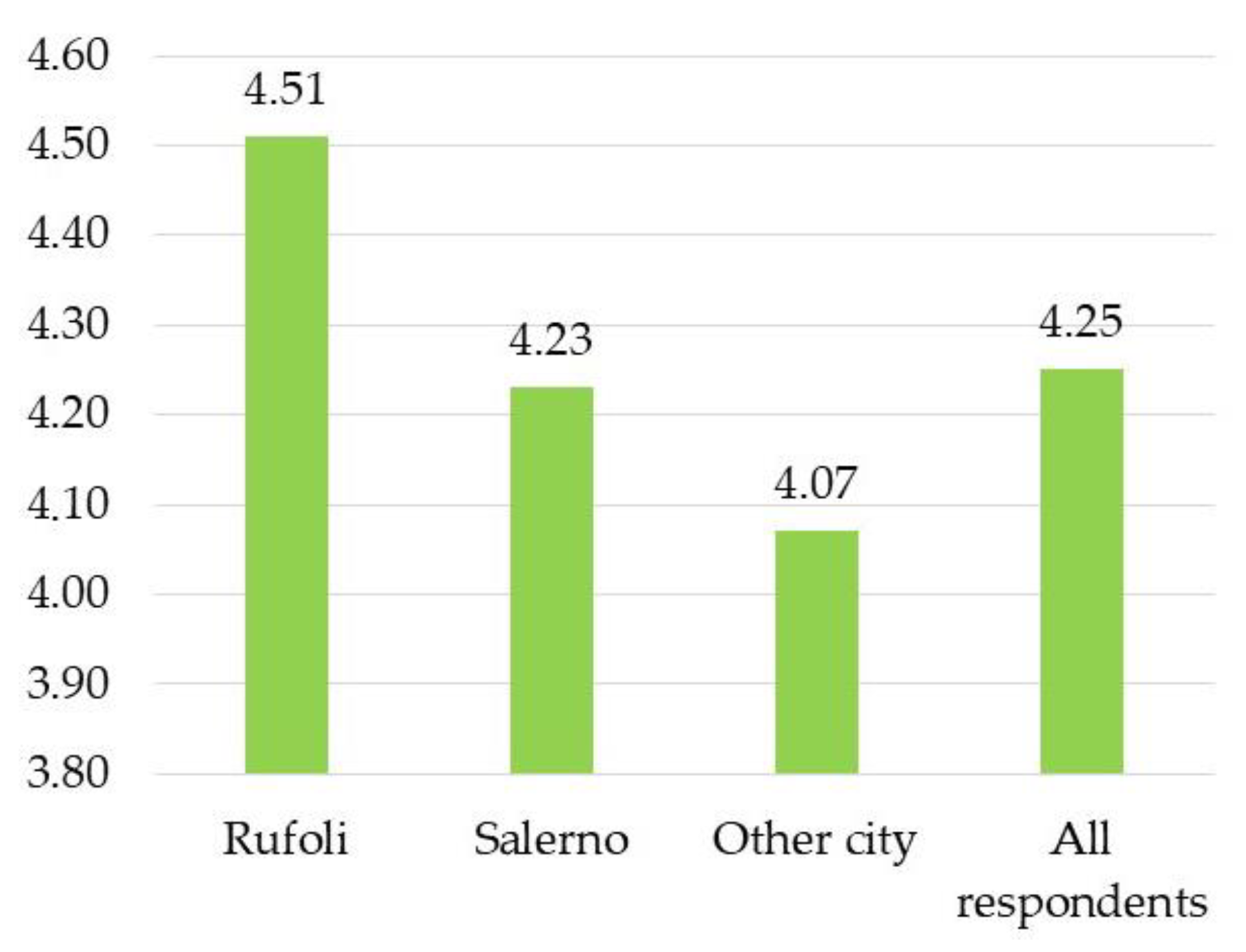

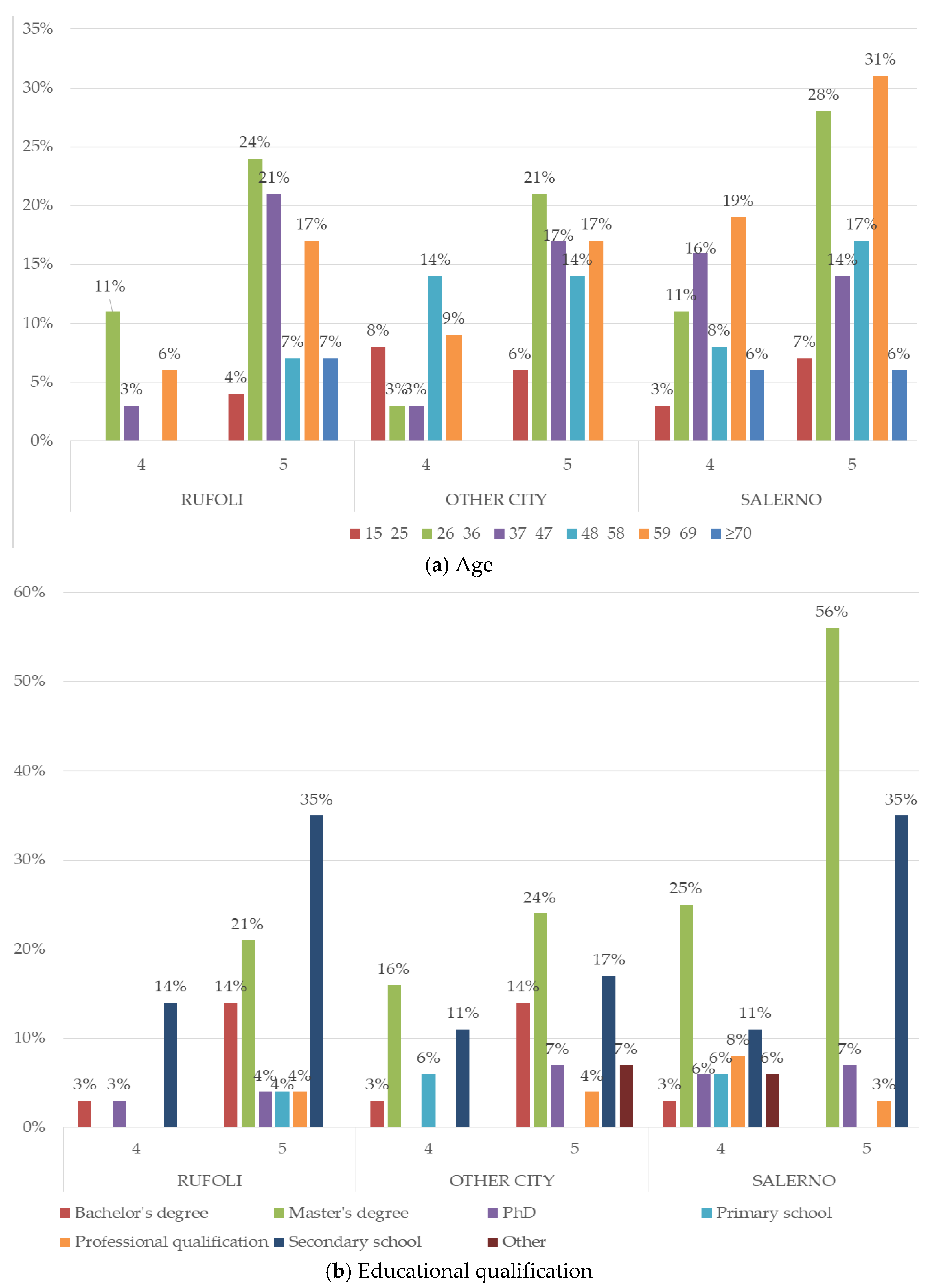

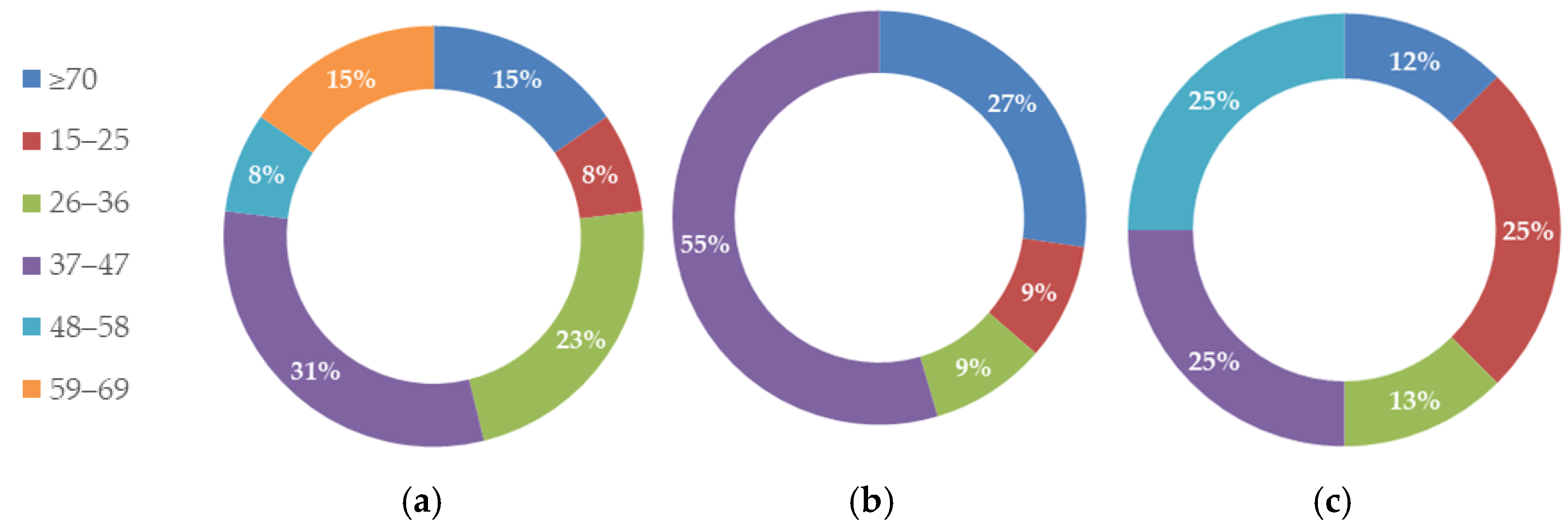

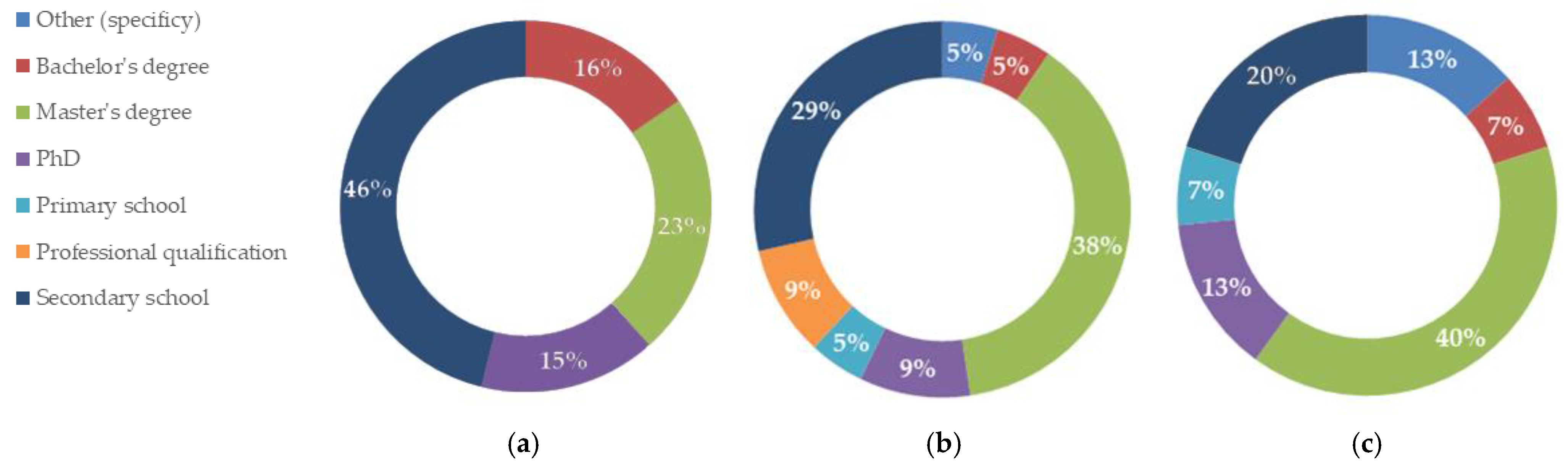

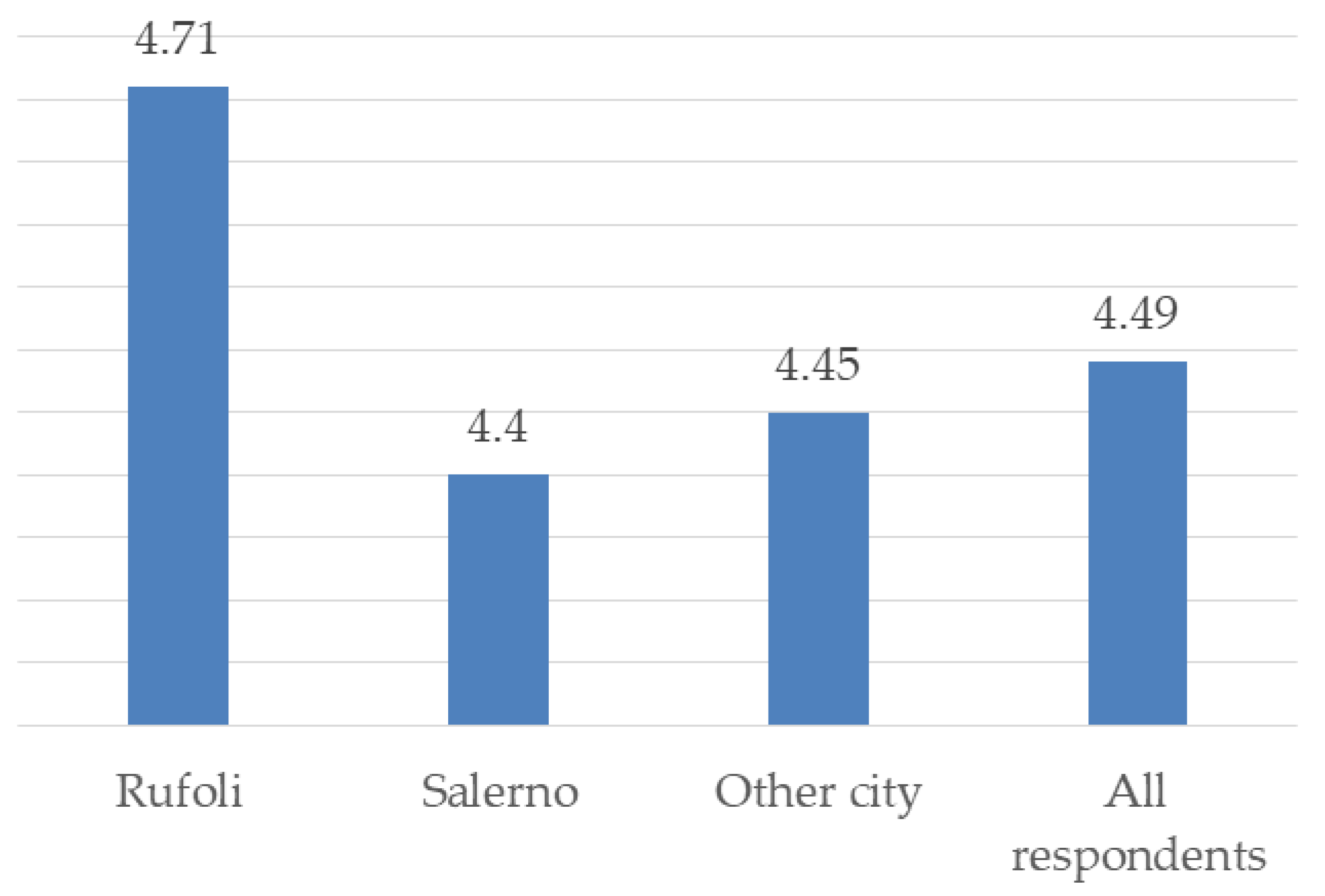

3. Results

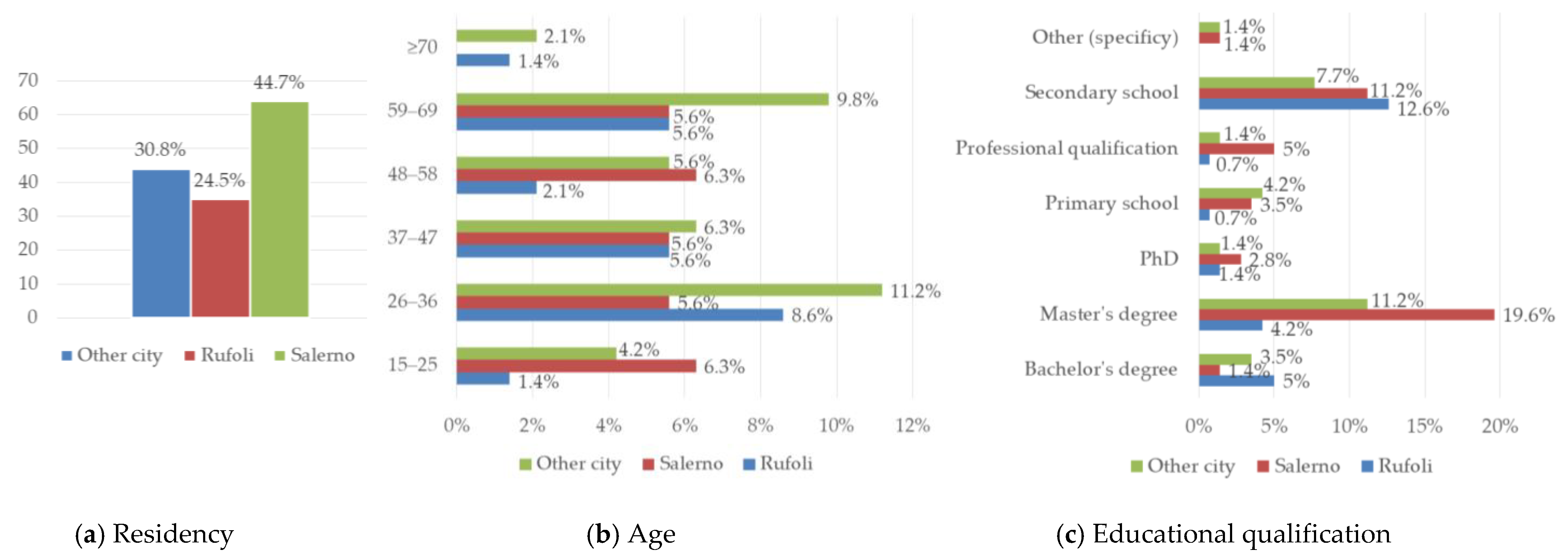

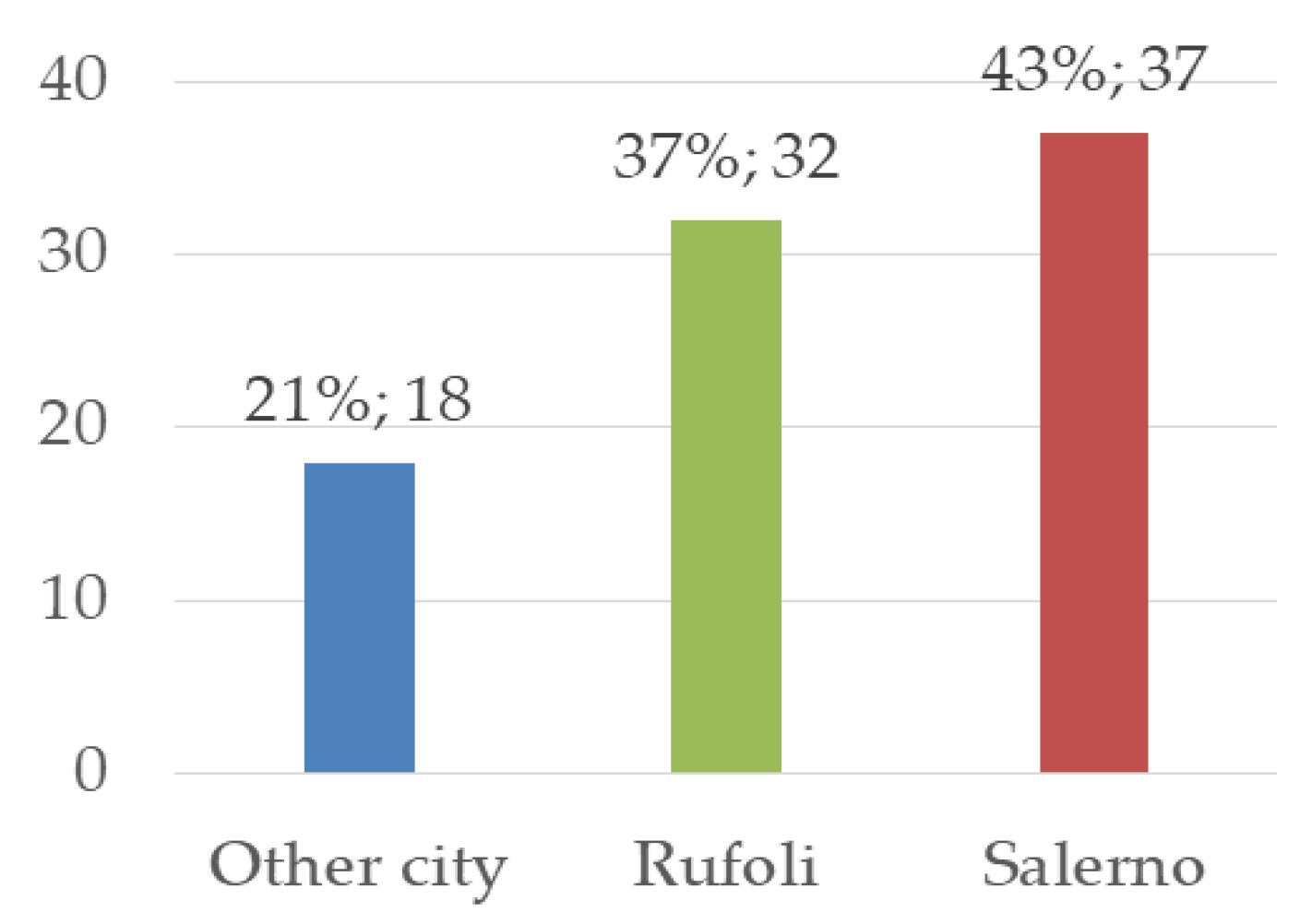

3.1. Rufoli Heritage Assessment Questionnaire

3.2. Towards an Action Plan for the Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage in Rufoli

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- In line with the HUL recommendation and the FC, the process included mapping cultural and natural heritage, recognizing diverse components of its complex value, and engaging the local community in collaborative actions for the adaptive reuse and regeneration of abandoned assets, activating informal and formal partnerships within a Heritage Community.

- Results of the mapping exercise, stakeholders’ engagement, and envisioning showed a proactive attitude of stakeholders, aiming at enlarging the heritage community and reaching out to citizens and institutions to co-develop a shared vision for the future of cultural and natural heritage of Rufoli in Salerno.

- A set of actions related to education, training, experiential visits, and re-activation of productive processes adopting circular and sustainable production and consumption models resulted widely acceptable and desirable. This implied the recognition of a “hidden” cultural demand from citizens and potential end-users, which can represent a robust base for the development of heritage-led entrepreneurial activities. The “entrepreneurial ecosystem” includes not only companies in a specific territory, but also knowledge providers such as university and research entities, financing bodies, local governments, large companies as “drivers” of growth for smaller start-up, and the entire community which can play a key role in demanding and co-creating culture-led opportunities for jobs, entertainment, education, and training.

- The questionnaire administered had a double result of both collecting data on the level of knowledge, interest, and agreement with respect to the strategic vision for the site of Rufoli, and informing and engaging the local community in a wider collective action. The results of the questionnaire showed an unexpected level of interest within the local community, which would encourage further action through a bottom-up approach. However, it should be also considered the role of private and public owners of heritage sites, which could feel “attacked” by groups of active citizens contesting abandonment and underuse of heritage resources. This kind of conflict between active communities and legal owners of heritage sites could hinder the potential for effective conservation action. Therefore, careful attention to dialogue and cooperation of all relevant actors should be given since the start of reuse and regeneration actions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Attributes/ Characteristics | Values (According to the Complex Social Value Theory, Fusco Girard 1987) | State of Conservation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient furnaces of clay tiles Tangible cultural heritage | Ancient furnaces made of bricks, with small openings to circulate air during the cooking process. 2 of them are still in use by the company “Fornaci De Martino”. Other furnaces are owned by private subjects, but abandoned. | Social-Cultural value: the furnaces are a unique testimony of the past ways to produce clay tiles (cotto), the local community recognize the furnaces and tradition of cotto making for local identity. | Environmental value: the furnaces represent a “circular” production model based on natural resources on site; a traditional process of recovery of pieces of tiles allows to avoid wastes and reuse materials for new products. | Economic value: two furnaces are still in use, the clay tiles is a high-level design product of artisanal quality, each tile is different from the other; this makes the production demanded for high-quality architectural design; educational and tourism activities (visits, workshops) are active but could be strengthened; a potential for recovery of other furnaces can be exploited. | Intrinsic Value: the furnaces are a unique testimony of the permanence over centuries of the clay tiles (cotto) making tradition; a circular model of production, based on local resources and no waste, is manifested in the furnaces site; the “spirit” of cotto making to provide materials for houses and buildings is still present in the site, today represented by the entrepreneurial activities inspired by past values and oriented to the future. | Two of them have been recovered by the company “Fornaci De Martino” and are in use. Other furnaces are in a state of abandonment and degrade. |

| Tradition of clay tiles (cotto) making Intangible cultural heritage | The only family today still able to cook clay tiles in ancient furnaces is linked to the company of “Fornaci De Martino”, owners of the two still working furnaces. This tradition has been transferred from father to son orally; the moment of cooking lasts two days, following procedures of fire making, windows closing and opening during the diverse hours and according to winds and weather; the role of women was to support men in this effort, being present during the days of cooking and providing them energy through food and wine. Sometimes external people are invited to attend. | Social-Cultural value: the tradition is a unique expression of cultural diversity and history, still conserved after centuries but at high risk of disappearing after the present generation of cotto makers. | Environmental value: the tradition of cotto cooking is grounded in a sustainable production model in synergy with the local environment; wind, sun, soil, water, are the elements of this tradition, which reports to the present the close connection with Nature coming from the past traditions. | Economic value: the intangible heritage has a high potential for sustainable economic value creation; the presence of this tradition can potentially greatly enhance the attractiveness of the peripheral eastern area of Salerno. | Intrinsic Value: the tradition of cotto making is deeply embedded in the “spirit of the place”, where the clay as primary material was present since ever; men worked in synergy with natural elements (wind, sun, water, soil…), re-generating the atmosphere of the site over time. | The tradition is still alive, however it remains at high risk of disappearing after the present generation of cotto makers. |

| Clay hills caving sites Natural heritage | The hills nearby the furnaces site is full of clay, that was used since ever for the production of tiles (cotto). | Social-Cultural value: Cultural and social values are linked to the awareness of the importance of this natural site for human activities. | Environmental Value: It has a clear environmental value linked to the ecosystem services it provides, particularly raw materials. | Economic value: The economic value is linked to raw materials extraction, and potentially to health recreation services associated to the presence of a natural site. The site represents the natural environment that allowed the production of cotto in the area. | Intrinsic Value: the tradition of cotto have determined a synergistic relationship between man and natural environment which, in the time, was shaping by the extractive activities related to the presence of clay, assuming a specific spatial identity. | The clay hill is conserved, still in use as a source of raw materials, according to a sustainable production model. |

| Archaeological remains dating back to Roman time Tangible cultural heritage | Archaeological remains dating back at least to Roman time are present in the whole eastern peripheral area of Salerno. | Social-Cultural value: The archaeological remains are a unique testimony of past civilizations in the area, with high cultural value. | Environmental Value: is potentially linked to the green areas integrated with archaeological remains. | Economic value: this value is linked to potential attractiveness of the area for visitors and residents. | Intrinsic Value: The uniqueness of the remains could reinforce the “sense of place” and identity of citizens, if well valorised. | Less-known, scarcely valorized, partially still to be discovered archaeological sites. Local associations take care of them, however the uniqueness of the remains could represent an element of attractiveness for the city. |

| Montestella Park Natural heritage Tangible cultural heritage (religious heritage present in the site) Intangible cultural heritage (religious celebrations, place linked to Salerno ancient Medical School). | The Mount is known for being the highest mount in the port city of Salerno (953 m). On the top of the mountain there is a religious site with a Church dedicated to the holy Mary, still active, in which a traditional celebration is organized every year. | Social-Cultural value: The Mount is a natural site in which religious heritage is present, holding cultural, social and environmental value. Local traditions linked to the site include the celebrations for the holy Mary in the place of the Church. | Environmental Value: it is believed that the Mount was the place for collecting medical herbs at the time of the Salerno ancient Medical School, dating back to the Middle Age. | Economic value: this value can be potentially linked to recreation activities. | Intrinsic Value: the Mount expresses the two most important aspects of local cultural identity. Indeed, on one hand it has value as memory of local spirituality linked to the cult of holy Mary, while on the other hand it is linked with the image of Salerno as the city of health and wellbeing, due to the presence of Salerno Medical School which still today represents an element to be valorized for a strong local brand identity. | The Mount was scarcely maintained, however in the last few years the Municipality of Salerno started recovery works to make accessible the hiking paths using public funding. The local community committed to opening up connection paths with the eastern neighbourhoods of the city. The Church is not very well conserved but used. |

| Autochthonous grape “Sanginella” Natural heritage Intangible cultural heritage (as local typical agronomic variety) | The grape variety of “Sanginella” is an ancient variety, autochthonous of the Salerno area, which was used in the past to make wine. | Social-Cultural value: the citizens of Salerno identified “Sanginella” as votive food dedicated to the patron, St Matthew, since its ripening period fell in the month dedicated to him. Furthermore, it was recognized as medical resource already used at the time of the Salerno Medical School to obtain medicines and remedies. | Environmental value: “Sanginella” is recognized as one of the few European autochthonous grapes still available today. Until the first half of the 20th century it was the only table grape in Salerno. Its cultivation was positively conditioned by the climate and the favourable exposure to the sun of the Salerno area and, in turn, has conditioned the morphological structure of the land, transforming it into the characteristic terraced landscapes still visible today. Today this variety is not cultivated, out of few family producers. | Economic value: there is plans of local agricultural associations to recover the variety enhancing its cultural, environmental and economic value. | Intrinsic Value: the “Sanginella” has an identity value for the people of Salerno as it is linked to the two most important aspects of local cultural identity: on the one hand the spiritual aspect linked to the cult of the patron, on the other hand the aspect linked to the strong brand identity element represented by Salerno Medical School. Furthermore, the specific interaction between man and nature to cultivate this product has influenced the spatial transformation of landscape, characterizing it in the time. | The variety is still conserved and available, but at high risk of disappearing. Recovery actions would be needed to avoid the loss of this peculiar natural and cultural heritage. |

References

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Faro, Portugal, 2005. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Council of Europe. Heritage and Beyond; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2009; Volume 477, ISBN 9789287166357. [Google Scholar]

- Zagato, L. The Notion of “Heritage Community” in the Council of Europe’s Faro Convention. Its Impact on the European Legal Framework. In Between Imagined Communities of Practic; Göttingen University Pres: Göttingen, Germany, 2015; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciati, P. La valorizzazione dell’eredità culturale in Italia: Atti del convegno. IL Cap. Cult. Stud. Value Cult. Herit. 2016, 5, 25.03.2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0477&from=en (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- European Commission. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on Cultural Heritage; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Culture Urban. Future: Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban. Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Habitat III Issue Papers 4—Urban. Culture and Heritage; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament TEXTS ADOPTED P8_TA-PROV(2017)0140 European Year of Cultural Heritage ***I 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0140_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Throsby, D. Cultural Capital. J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 3–12. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:kap:jculte:v:23:y:1999:i:1:p:3-12 (accessed on 3 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ost, C. A Guide for Heritage Economics in Historic Cities—Values, Indicators, Maps, and Policies; ICHEC Brussels School of Management: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ost, C. Mapping Heritage Economics for Spatial Analysis in Historic City Cores. In The Economics of Uniqueness. Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; Licciardi, G., Amirtahmasebi, R., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 245–283. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Guidance on Heritage Impact Assessments for Cultural World Heritage Properties; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III). 2017. Available online: https://uploads.habitat3.org/hb3/NUA-English-With-Index-1.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Pinton, S.; Zagato, L. Cultural Heritage Scenarios 2015–2017; Edizioni Ca’ Foscari: Venezia, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788869691799. Available online: https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/media/pdf/books/978-88-6969-225-3/978-88-6969-225-3_MQpSP8B.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- EUTROPIAN. Funding the Cooperative City; Patti, D., Polyák, L., Eds.; Cooperative City Books: Vienna, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-3-9504409-0-4. [Google Scholar]

- Garzillo, C.; Balenciaga, I.; Izulain, A.; Rangil-Escribano, T.; Wildman, A. Circular Governance Models for Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage, Horizon 2020 CLIC Deliverable D3.4. 2019. Available online: https://www.clicproject.eu/files/D3-4.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Bosone, M.; Micheletti, S.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Garzillo, C.; Wildman, A. Towards a circular governance for the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage. Bdc. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2019, 19, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerquetti, M.; Nanni, C.; Vitale, C. Managing the landscape as a common good? Evidence from the case of “Mutonia” (Italy). Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, C. Mapping the New Commons. SSRN Electron. J. 2008. Available online: https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=sul (accessed on 15 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- European Commission Study of Heritage Houses for Europe. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/it/publication-detail/-/publication/bc6dd18f-ddba-11e9-9c4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-fr (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Cerreta, M.; La Rocca, L.; Elefante, A. San Sebastiano del Monte dei Morti Living Lab (SSMOLL): Un processo di riuso adattivo community-driven. In Proceedings of the LVII Incontro di Studi Ce.S.E.T. Sviluppo Sostenibile, Economia e Città Circolare: Processi e metodi di valutazione, Naples, Italy, 12–13 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garzillo, C. Artistic and Curatorial Power in Cities’ Historic Spaces. Eur. J. Creat. Pract. Cities Landsc. 2020, 3, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A. Circular economy and cultural heritage/landscape regeneration. Circular business, financing and governance models for a competitive Europe. Bdc. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2017, 1, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. Implementing the circular economy: The role of cultural heritage as the entry point. Which evaluation approaches? Bdc. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2019, 19, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Perry, W. The Synonymous, Etymological, and Pronouncing English Dictionary: In Which the Words Are Deduced from Their Originals, Their Part of Speech Distinguished, Their Pronunciation Pointed Out, and Their Synongma Collected; John Walker: London, UK, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; Michigan Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Santagata, W.; Bertacchini, E.; Bravo, G.; Marrelli, M. Cultural Commons and Cultural Communities. In Proceedings of the 13th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons, Hyderabad, India, 10–14 January 2011; pp. 10–14. Available online: https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/7359/297.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Ostrom, E. Design Principles and Threats to Sustainable Organizations That Manage Commons. Workshop Working Paper W99-6. 1999. Available online: http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/5465/Design%20Principles%20and%20Threats%20to%20Sustainable%20Organizations%20That%20Manage%20Commons.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Richerson, P.J.; Boyd, R. Not by Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. Biol. Philos. 2008, 23, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senato della Repubblica Italiana Disegno di Legge Delega al Governo per la Modifica del Codice Civile in Materia di beni Pubblici. 2010. Available online: https://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/DF/217244.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Sacconi, L.; Ottone, S. Beni Comuni e Cooperazione; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015; ISBN 978-8815253767. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Carmosino, C. Il Valore del Patrimonio Culturale fra Italia e Europa. La Convenzione Quadro del Consiglio d’Europa sul Valore del Patrimonio Culturale per la società. Aedon 2013, 1. Available online: http://www.aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2013/1/carmosino.htm (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Fusco Girard, L. Risorse Architettoniche e Culturali: Valutazioni e Strategie di Conservazione; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bonesio, L. Paesaggio, Identità e Comunità Tra Locale e Globale; Mimesis Edizioni: Milano, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-88-5754-512-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, J. Heritage expertise and the everyday: Citizens and authority in the twenty-first century. In Who Needs Experts? Counter-Mapping Cultural Heritage; Schofield, J., Ed.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2014; pp. 1–11. ISBN 9781472401786. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy. 2017. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/GA2017_Delhi-Declaration_20180117_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G.; Dragićević-Šešić, M.; Rogač-Mijatović, L.; Auclair, E.; Soini, K. The Faro Convention, a New Paradigm for Socially–and Culturally–Sustainable Heritage Action? Culture 2014, 8, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.K.; Paavola, J.; Cooper, P.; Farber, S.; Jessamy, V.; Georgiou, S. Valuing nature: Lessons learned and future research directions. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Habitat III Preparatory Process: Urban Dialogue Reports—“Social Cohesion and Equity” 2015. Available online: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/preparatory-process/urban-dialogue-reports/urban-dialogues-draft-zero-summaries/ (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F.; Gravagnuolo, A. Matera: City of nature, city of culture, city of regeneration. Towards a landscape-based and culture-based urban circular economy. Aestimum 2019, 74, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, C. Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research. Educ. Action Res. 1993, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, J. The history of action research. In Action Research Electronic Reader; Hughes, I., Ed.; The University of Sydney: Camperdown, Australia, 1995; Available online: http://www.fionawangstudio.com/ddcontent/Web/action_research/readings/Masters_1995_history%20of%20action%20research.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Mills, C.W. The Sociological Imagination. Miss. Val. Hist. Rev. 1959, 46, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, K.; Borkowska-Waszak, S.; Domaradzka-Widła, A.; Park, Y. Policy labs: The next frontier of policy design and evaluation? Policy Politics 2020, 48, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, K.; Borkowska-Waszak, S.; Domaradzka-Widla, A.; Park, Y. The Craft of Policy Labs: An Overview of Methods Applied for Development and Testing of Policy Solutions. In the Rise of Policy Labs. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Public Policy (ICPP3), Singapore, 28–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Avallone, G. Introduzione alla Tesi di Laurea Magistrale In Architettura, Università di Napoli Federico II. Dipartimento di Architettura. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornaci de Martino. Available online: www.fornacedemartino.it. (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Fondo Ambiente Italiano. Available online: www.fondoambiente.it. (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Rubino, G. Le Fabbriche del Sud: Architettura e Archeologia del Lavoro; Giannini: Naples, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo di Caprio, N. Ceramica in Archeologia, 2. Antiche Tecniche di Lavorazione e Moderni Metodi di Indagine; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Persico, P. Identità e Sviluppo; Pietro La Veglia editore: Salerno, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ler, S. Le Fornaci di Rufoli. la Via Dell’acqua, la Via del Fuoco; La Veglia editore: Salerno, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo, C. L’Impastacrita. Camporiv. Trimest. Cult. Del Mezzog. 1981, 7, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sinno, A. Commercio e Industrie Nel Salernitano Dal XIII Ai Primordi del XIX Secolo; Camera di Commercio Industria e Agricoltura di Salerno: Salerno, Italy, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Panebianco, V. La Colonia Romana di Salernum: Introduzione Allo Studio di Salerno Romana; Linotypografia Spadafora: Salerno, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Hul Guidebook. Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments. A Practical Guide to Unesco’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region (WHITRAP): Shanghai, China; Ballarat, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.W. Stakeholder analysis: A pivotal practice of successful projects. In Proceedings of the Project Management Institute Annual Seminars & Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 7 September 2000; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge: PMBOK Guide, 5th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 1996; ISBN 9781628251845. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Malangone, V. Valutazioni multi-metodologiche per il Paesaggio Storico Urbano: La Valle dei Mulini di Amalfi. Bdc. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2014, 14, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Berejikian, J. Reconstructive Democratic Theory. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1993, 87, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronti, A.; Nobile, G.; Pagliarino, E. La Stakeholder Analysis per la gestione dei beni comuni e delle risorse naturali: Metodologie e letteratura. Quad. IRCrES-CNR 2018, 4, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Città e del Territorio; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1997; ISBN 978-88-464-0182-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. Genius Loci: The evaluation of places between instrumental and intrinsic values. Bdc. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2019, 19, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. The “Intrinsic Value” of Cultural Heritage as Driver for Circular Human-Centered Adaptive Reuse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. The circular economy in transforming a died heritage site into a living ecosystem, to be managed as a complex adaptive organism. Aestimum 2021, 77, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation. Herit. Soc. 2013, 60, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; D’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.; Atkinson, G.; Mourato, S. Total Economic Value. In Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Recent Developments; Organ. Econ. Co-Op. Dev: Paris, France, 2006; ISBN 9789264010055. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K. The Place of Economic Values in Environmental Valuation. In Valuing Environmental Preferences: Theory and Practice of the Contingent Valuation Method in the US, EU, and Developing Countries; Bateman, I.J., Willis, K.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 17–41. ISBN 9780199248919. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; JHU press: London, UK, 1989; ISBN 0745002250. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe Faro Convention Network (FCN). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-community#portlet_56_INSTANCE_5mjl2VH0zeQr (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Brown, J.; Isaacs, D. The World Café: Shaping our Future Through Conversations that Matter; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pintossi, N.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; Pereira Roders, A. Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage in Amsterdam: Identifying Challenges and Solutions through the Historic Urban Landscape Approach. In LDE Heritage Conference on Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Proceedings; Pottgiesser, U., Fatoric, S., Hein, C., de Maaker, E., Pereira Roders, A., Eds.; TU Delft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pintossi, N.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; Pereira Roders, A. Assessing Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Practices: Multi-Scale Challenges and Solutions in Rijeka. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, C.; Saleh, R. Horizon 2020 CLIC Deliverable D3.3 Maps of Landscape Perceptions. 2019. Available online: https://www.clicproject.eu/files/D3-3.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0803971776. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Giovene di Girasole, E. Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder Macro–Categories | Stakeholder Categories |

|---|---|

| PROMOTERS | Research institutions Local Government Heritage Authorities Education institutions |

| OPERATORS | Civil society organization Enterprises |

| USERS | Citizens Tourists/visitors |

| Count | Average | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Respondents | 143 | 44.2 | 15.5 |

| Rufoli | 35 | 43.6 | 15.8 |

| Salerno | 64 | 44.1 | 15.5 |

| Other City | 44 | 44.0 | 15.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812

Gravagnuolo A, Micheletti S, Bosone M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812

Chicago/Turabian StyleGravagnuolo, Antonia, Serena Micheletti, and Martina Bosone. 2021. "A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812

APA StyleGravagnuolo, A., Micheletti, S., & Bosone, M. (2021). A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability, 13(9), 4812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812