The Impact of Sex and Personality Traits on Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Question 1 (Q1).

- Are there any differences in the use of specific social media types attributable to sex and personality traits among young adults (18–29)?

- Question 2 (Q2).

- Are there differences in social media use drivers among sexes and personality features?

- Question 3 (Q3).

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected social media use?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Use and Power of Social Media

2.2. Factors Influencing the Use of Social Media

2.3. Social Media in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Questionnaire

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

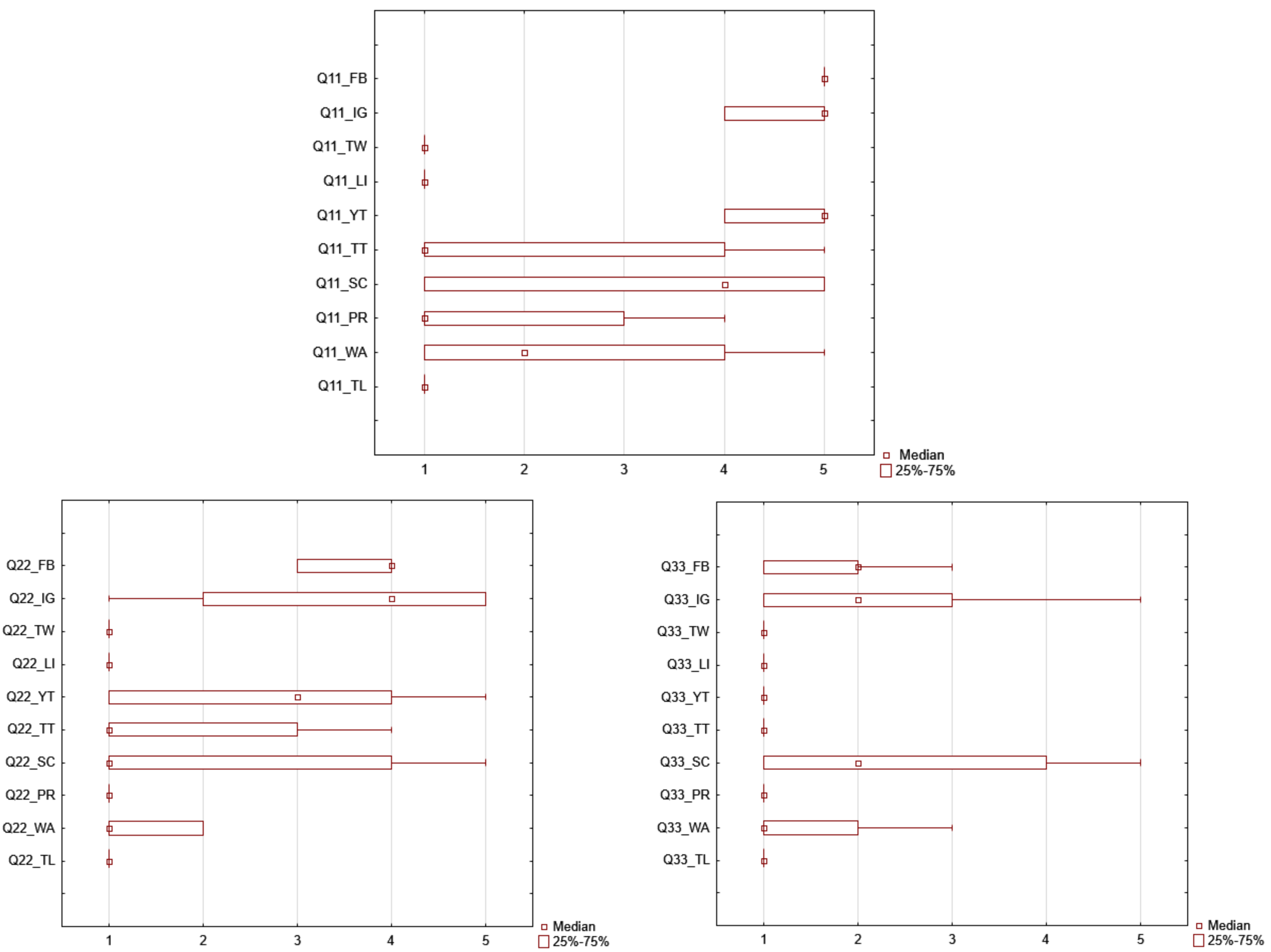

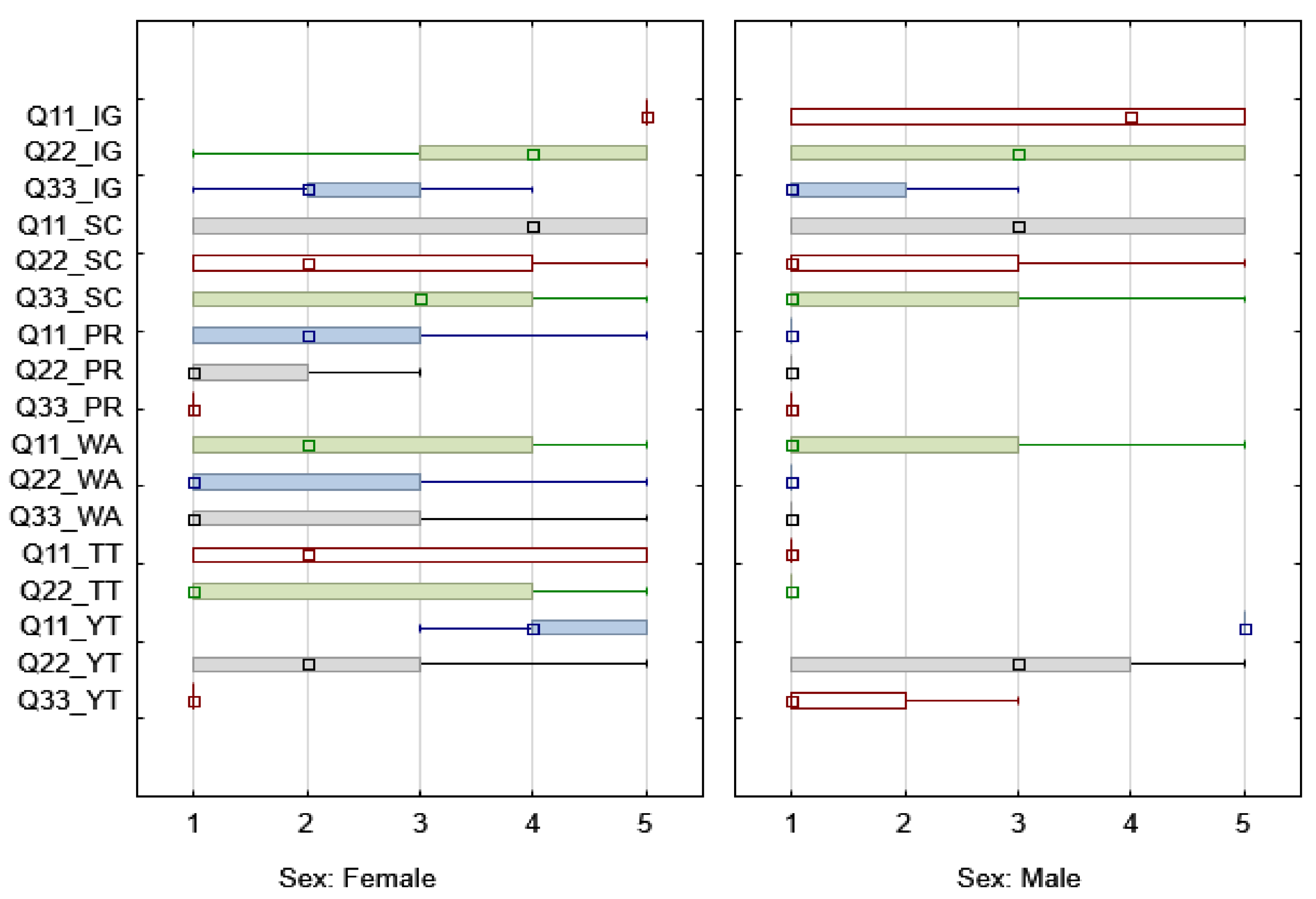

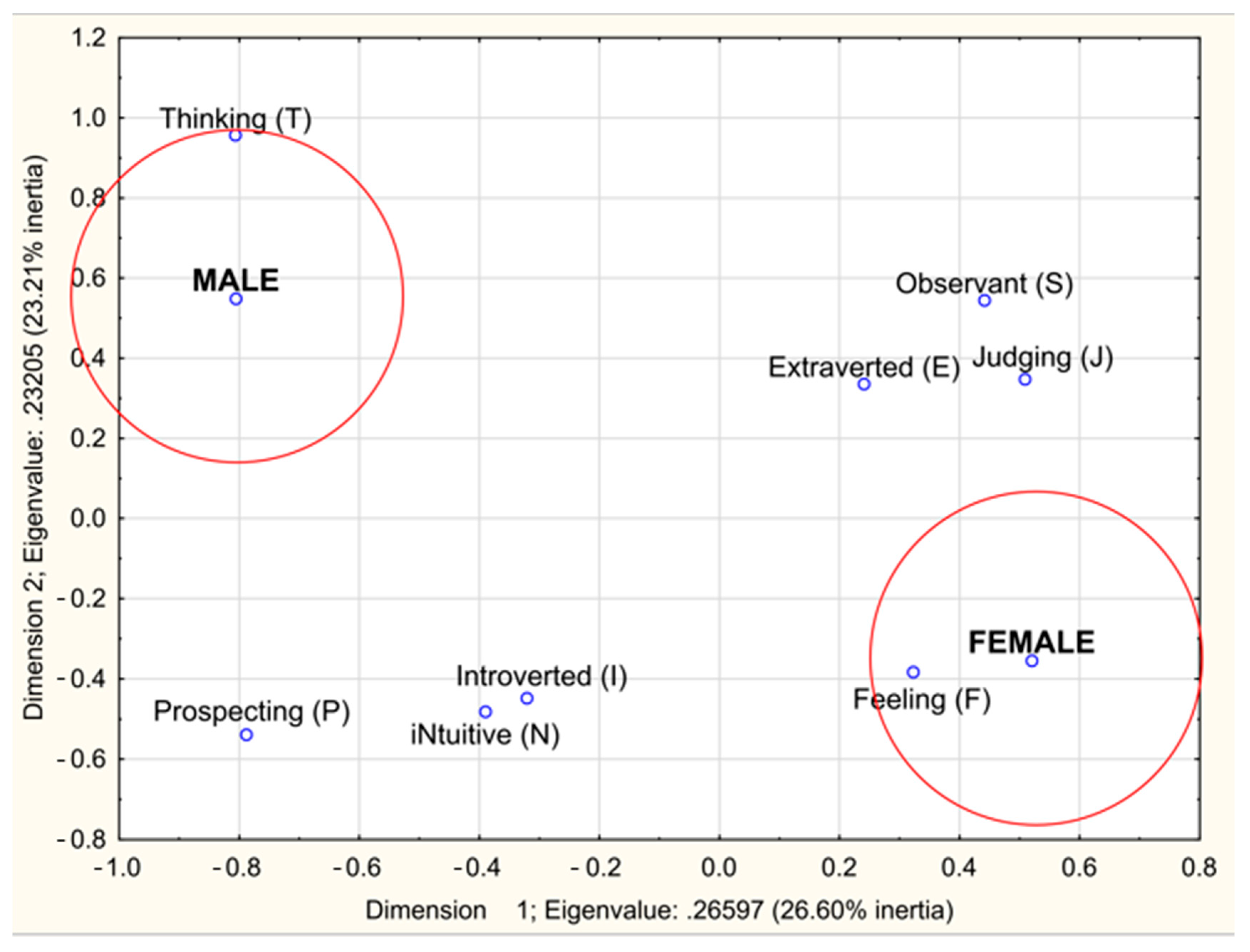

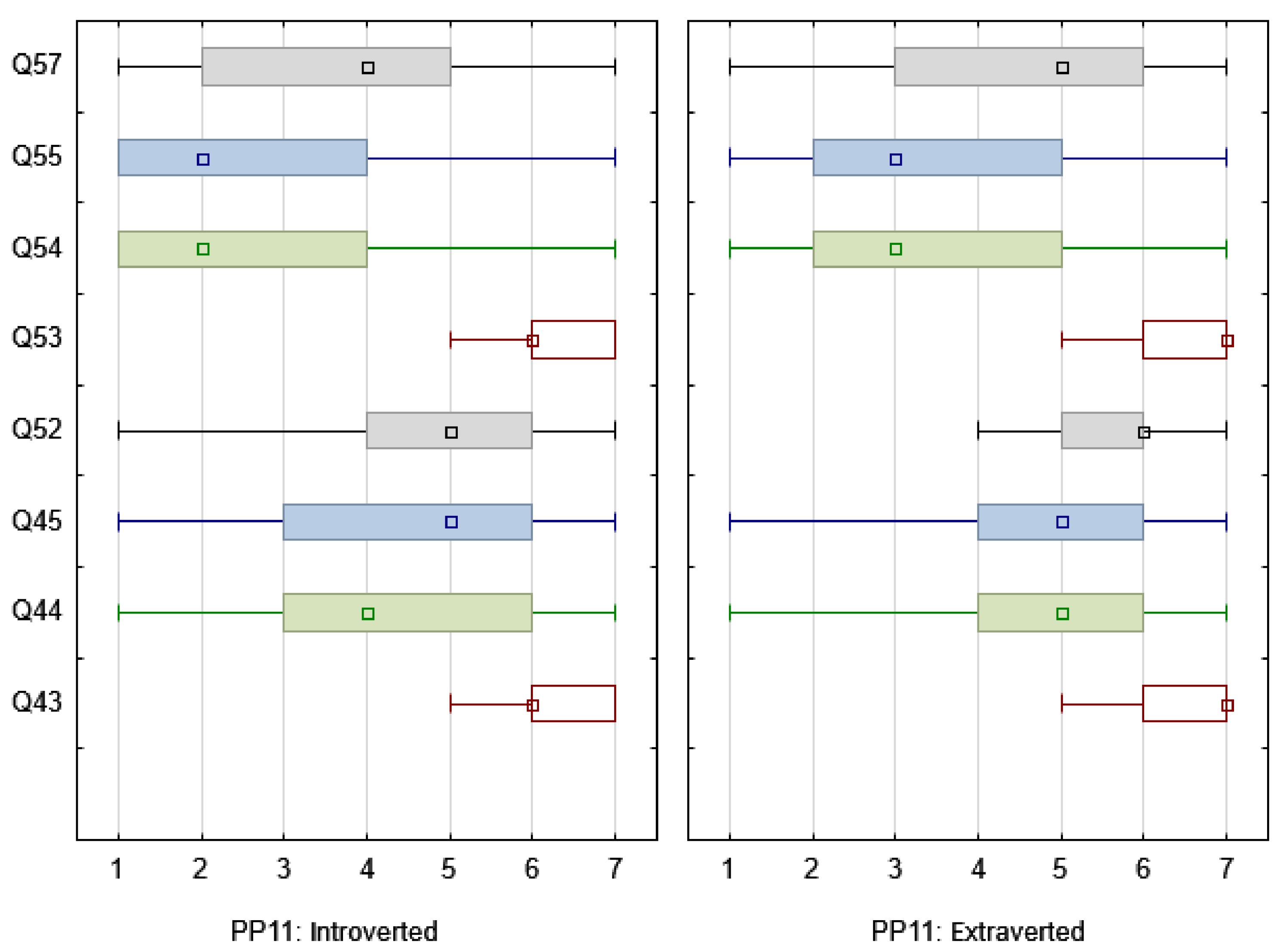

4.1. Data Analysis by Sex and Personality Traits

4.2. The Impact of COVID-19 on Social Media Use Changes

4.3. Forecasts of Social Media Popularity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Practical Implications and Limitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Architect (INTJ) | Logician (INTP) | Commander (ENTJ) | Debater (ENTP) |

| Advocate (INFJ) | Mediator (INFP) | Protagonist (ENFJ) | Campaigner (ENFP) |

| Logistician (ISTJ) | Defender (ISFJ) | Executive (ESTJ) | Consul (ESFJ) |

| Virtuoso (ISTP) | Adventurer (ISFP) | Entrepreneur (ESTP) | Entertainer (ESFP) |

| Measurements and Questions | |

|---|---|

| I use Facebook… | |

| Q41 | … because it’s free |

| Q42 | … because it’s easy to use |

| Q43 | … because many of my close friends use it |

| Q44 | … because of its interesting functionality |

| Q45 | … because it works fast |

| Q46 | … because it gains popularity |

| Q47 | … because I’m used to it |

| Q48 | … because I trust it is secure |

| Q49 | … because it is popular (high market share) |

| Q50 | … because it has a free online messenger |

| Q51 | … because I want to be up to date with recent news |

| Q52 | … because one can learn interesting things from others |

| Q53 | … to keep in touch with friends |

| Q54 | … because I occasionally like to share interesting information publicly |

| Q55 | … because I occasionally like to express my opinion publicly |

| Q56 | … for fun (silly videos, images, etc.) |

| Q57 | … out of curiosity (to learn about the lives of others) |

| Q58 | … because I need to (quick communication and exchange of data at school/university) |

| Personality | PP11 | PP12 | PP13 | PP14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Introverted (I) | 1– Intuitive (N) | 1—Feeling (F) | 1—Judging (J) | |

| 2—Extraverted (E) | 2—Observant (S) | 2—Thinking (T) | 2—Prospecting (P) | |

| Architect (INTJ) | I | N | T | J |

| Commander (ENTJ) | E | N | T | J |

| Debater (ENTP) | E | N | T | P |

| Logician (INTP) | I | N | T | P |

| Campaigner (ENFP) | E | N | F | P |

| Mediator (INFP) | I | N | F | P |

| Protagonist (ENFJ) | E | N | F | J |

| Advocate (INFJ) | I | N | F | J |

| Entertainer (ESFP) | E | S | F | P |

| Adventurer (ISFP) | I | S | F | P |

| Entrepreneur (ESTP) | E | S | T | P |

| Virtuoso (ISTP) | I | S | T | P |

| Consul (ESFJ) | E | S | F | J |

| Logistician (ISTJ) | I | S | T | J |

| Defender (ISFJ) | I | S | F | J |

| Executive (ESTJ) | E | S | T | J |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean ± SD | Mdn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q58 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1.92 | 5.97 | 25.80 | 63.97 | 6.44 ± 1 | 7 |

| Q43 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 1.71 | 10.02 | 28.36 | 58.21 | 6.38 ± 0.95 | 7 |

| Q53 | 1.49 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 10.66 | 29.85 | 55.86 | 6.32 ± 1.07 | 7 |

| Q50 | 2.99 | 1.49 | 2.13 | 3.84 | 9.17 | 22.81 | 57.57 | 6.13 ± 1.41 | 7 |

| Q47 | 2.56 | 0.43 | 2.13 | 3.20 | 18.55 | 31.13 | 42.00 | 5.96 ± 1.28 | 6 |

| Q42 | 3.62 | 3.20 | 3.41 | 5.97 | 21.32 | 40.09 | 22.39 | 5.48 ± 1.46 | 6 |

| Q51 | 3.41 | 4.05 | 7.46 | 5.54 | 26.87 | 27.51 | 25.16 | 5.32 ± 1.57 | 6 |

| Q56 | 5.33 | 3.20 | 4.48 | 5.97 | 29.21 | 27.29 | 24.52 | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 6 |

| Q52 | 5.12 | 2.35 | 6.61 | 6.40 | 27.08 | 30.70 | 21.75 | 5.27 ± 1.57 | 6 |

| Q41 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1.92 | 5.97 | 25.80 | 63.97 | 5.21 ± 1.77 | 6 |

| Q49 | 8.53 | 4.90 | 8.74 | 14.29 | 23.24 | 18.34 | 21.96 | 4.82 ± 1.83 | 5 |

| Q45 | 5.97 | 6.82 | 10.23 | 13.22 | 27.29 | 23.24 | 13.22 | 4.72 ± 1.67 | 5 |

| Q44 | 5.12 | 6.40 | 12.37 | 19.19 | 27.51 | 18.55 | 10.87 | 4.57 ± 1.59 | 5 |

| Q57 | 13.22 | 9.59 | 14.07 | 13.43 | 25.80 | 15.99 | 7.89 | 4.09 ± 1.82 | 4 |

| Q46 | 11.51 | 9.59 | 17.91 | 23.24 | 13.65 | 13.65 | 10.45 | 4.01 ± 1.8 | 4 |

| Q48 | 13.65 | 10.23 | 15.35 | 28.78 | 21.32 | 7.04 | 3.62 | 3.7 ± 1.59 | 4 |

| Q54 | 26.23 | 17.70 | 18.76 | 11.30 | 13.01 | 7.89 | 5.12 | 3.11 ± 1.84 | 3 |

| Q55 | 26.01 | 21.54 | 17.48 | 9.17 | 14.50 | 5.76 | 5.54 | 3.04 ± 1.83 | 3 |

| Variable | All | Male | Female | (I) | (E) | (N) | (S) | (T) | (F) | (P) | (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q58 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q43 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Q53 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Q50 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Q47 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Q42 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Q51 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 7 |

| Q56 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| Q52 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 |

| Q41 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 10 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | 0.4909 | - | 4.71 ± 0.61 | 4.68 ± 0.67 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 3.54 ± 1.69 | 4.47 ± 1.24 |

| Q11_TW | 0.4737 | - | 1.56 ± 1.24 | 1.38 ± 0.93 |

| Q11_LI | 0.4329 | - | 1.15 ± 0.54 | 1.14 ± 0.58 |

| Q11_YT | 0.0000 | *** | 4.77 ± 0.52 | 4.26 ± 0.76 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.65 ± 1.28 | 2.71 ± 1.74 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 2.76 ± 1.74 | 3.46 ± 1.65 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0000 | *** | 1.26 ± 0.67 | 2.34 ± 1.3 |

| Q11_WA | 0.0034 | ** | 2.13 ± 1.45 | 2.54 ± 1.51 |

| Q11_TL | 0.0000 | *** | 1.07 ± 0.34 | 1.25 ± 0.65 |

| Q22_FB | 0.1500 | - | 3.26 ± 1.41 | 3.48 ± 1.21 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 2.83 ± 1.68 | 3.94 ± 1.38 |

| Q22_TW | 0.1100 | - | 1.34 ± 0.88 | 1.27 ± 0.86 |

| Q22_LI | 0.8648 | - | 1.07 ± 0.36 | 1.06 ± 0.36 |

| Q22_YT | 0.0022 | ** | 2.94 ± 1.52 | 2.49 ± 1.3 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.42 ± 1.11 | 2.16 ± 1.59 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.9 ± 1.45 | 2.58 ± 1.64 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0000 | *** | 1.07 ± 0.31 | 1.73 ± 1.18 |

| Q22_WA | 0.0002 | *** | 1.46 ± 1.01 | 1.89 ± 1.31 |

| Q22_TL | 0.0015 | ** | 1.02 ± 0.21 | 1.12 ± 0.47 |

| Q33_FB | 0.8559 | - | 2.03 ± 1.08 | 1.97 ± 0.89 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 1.65 ± 0.87 | 2.29 ± 0.92 |

| Q33_TW | 0.5153 | - | 1.1 ± 0.46 | 1.1 ± 0.54 |

| Q33_LI | 0.5576 | - | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.27 |

| Q33_YT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.59 ± 0.96 | 1.18 ± 0.5 |

| Q33_TT | 0.5956 | - | 1.11 ± 0.54 | 1.13 ± 0.57 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 2.02 ± 1.47 | 2.81 ± 1.65 |

| Q33_PR | 0.0008 | *** | 1 ± 0 | 1.11 ± 0.49 |

| Q33_WA | 0.0004 | *** | 1.45 ± 1.04 | 1.8 ± 1.25 |

| Q33_TL | 0.0129 | * | 1.01 ± 0.15 | 1.06 ± 0.29 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q41 | 0.1143 | - | 5 ± 1.94 | 5.35 ± 1.63 |

| Q42 | 0.0484 | * | 5.28 ± 1.61 | 5.61 ± 1.34 |

| Q43 | 0.6263 | - | 6.43 ± 0.85 | 6.34 ± 1.02 |

| Q44 | 0.0215 | * | 4.32 ± 1.75 | 4.73 ± 1.45 |

| Q45 | 0.0073 | ** | 4.41 ± 1.86 | 4.92 ± 1.51 |

| Q46 | 0.0309 | * | 3.79 ± 1.93 | 4.15 ± 1.7 |

| Q47 | 0.1383 | - | 5.88 ± 1.3 | 6.02 ± 1.26 |

| Q48 | 0.0027 | ** | 3.42 ± 1.8 | 3.87 ± 1.41 |

| Q49 | 0.7724 | - | 4.76 ± 2.03 | 4.85 ± 1.68 |

| Q50 | 0.7946 | - | 6.14 ± 1.42 | 6.13 ± 1.41 |

| Q51 | 0.0659 | - | 5.09 ± 1.75 | 5.46 ± 1.42 |

| Q52 | 0.0748 | - | 5.03 ± 1.79 | 5.42 ± 1.39 |

| Q53 | 0.0194 | * | 6.21 ± 1.09 | 6.38 ± 1.04 |

| Q54 | 0.0136 | * | 2.91 ± 1.96 | 3.24 ± 1.75 |

| Q55 | 0.2682 | - | 2.99 ± 1.97 | 3.07 ± 1.73 |

| Q56 | 0.5394 | - | 5.2 ± 1.75 | 5.37 ± 1.49 |

| Q57 | 0.0001 | *** | 3.67 ± 1.87 | 4.35 ± 1.74 |

| Q58 | 0.7017 | - | 6.42 ± 1.01 | 6.46 ± 1 |

| F1 | 0.0004 | *** | 503.73 ± 386.48 | 597.16 ± 343.11 |

| F2 | 0.3161 | - | 67.35 ± 94.97 | 71.77 ± 95.18 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Age (18–21) | Age (22–25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | 0.5987 | - | 4.69 ± 0.64 | 4.65 ± 0.7 |

| Q11_IG | 0.2501 | - | 4.2 ± 1.43 | 4.01 ± 1.56 |

| Q11_TW | 0.7950 | - | 1.47 ± 1.08 | 1.41 ± 0.99 |

| Q11_LI | 0.0000 | *** | 1.05 ± 0.28 | 1.4 ± 0.93 |

| Q11_YT | 0.1122 | - | 4.43 ± 0.75 | 4.58 ± 0.59 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0000 | *** | 2.55 ± 1.72 | 1.58 ± 1.22 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 3.48 ± 1.66 | 2.49 ± 1.63 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0000 | *** | 2.06 ± 1.26 | 1.48 ± 0.94 |

| Q11_WA | 0.0131 | * | 2.27 ± 1.45 | 2.69 ± 1.59 |

| Q11_TL | 0.3589 | - | 1.19 ± 0.54 | 1.17 ± 0.66 |

| Q22_FB | 0.0313 | * | 3.5 ± 1.23 | 3.13 ± 1.43 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0125 | * | 3.65 ± 1.54 | 3.21 ± 1.66 |

| Q22_TW | 0.7714 | - | 1.31 ± 0.89 | 1.3 ± 0.86 |

| Q22_LI | 0.0000 | *** | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 1.15 ± 0.52 |

| Q22_YT | 0.3357 | - | 2.71 ± 1.4 | 2.57 ± 1.44 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0007 | *** | 2.04 ± 1.56 | 1.43 ± 1.05 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0001 | *** | 2.52 ± 1.64 | 1.8 ± 1.35 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0448 | * | 1.52 ± 1.03 | 1.34 ± 0.91 |

| Q22_WA | 0.7342 | - | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.74 ± 1.25 |

| Q22_TL | 0.6398 | - | 1.08 ± 0.38 | 1.11 ± 0.45 |

| Q33_FB | 0.6021 | - | 1.98 ± 0.95 | 2.08 ± 1.08 |

| Q33_IG | 0.2574 | - | 2.08 ± 0.94 | 1.98 ± 0.99 |

| Q33_TW | 0.2690 | - | 1.12 ± 0.54 | 1.07 ± 0.44 |

| Q33_LI | 0.0000 | *** | 1 ± 0 | 1.09 ± 0.46 |

| Q33_YT | 0.3028 | - | 1.33 ± 0.77 | 1.36 ± 0.68 |

| Q33_TT | 0.1268 | - | 1.15 ± 0.6 | 1.06 ± 0.37 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 2.77 ± 1.65 | 1.77 ± 1.28 |

| Q33_PR | 0.6801 | - | 1.07 ± 0.38 | 1.06 ± 0.43 |

| Q33_WA | 0.1452 | - | 1.6 ± 1.12 | 1.83 ± 1.32 |

| Q33_TL | 0.9616 | - | 1.05 ± 0.27 | 1.03 ± 0.17 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Age (18–21) | Age (22–25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q41 | 0.1879 | - | 5.27 ± 1.73 | 4.95 ± 1.91 |

| Q42 | 0.6933 | - | 5.57 ± 1.38 | 5.27 ± 1.63 |

| Q43 | 0.8968 | - | 6.38 ± 0.94 | 6.35 ± 1.02 |

| Q44 | 0.9600 | - | 4.66 ± 1.54 | 4.35 ± 1.63 |

| Q45 | 0.5027 | - | 4.73 ± 1.65 | 4.64 ± 1.74 |

| Q46 | 0.9208 | - | 4.02 ± 1.75 | 3.91 ± 1.96 |

| Q47 | 0.0482 | * | 5.99 ± 1.24 | 5.94 ± 1.38 |

| Q48 | 0.0024 | ** | 3.81 ± 1.54 | 3.43 ± 1.62 |

| Q49 | 0.4275 | - | 4.82 ± 1.77 | 4.78 ± 2 |

| Q50 | 0.0204 | * | 6.15 ± 1.41 | 6.04 ± 1.47 |

| Q51 | 0.8279 | - | 5.38 ± 1.52 | 5.15 ± 1.64 |

| Q52 | 0.6662 | - | 5.32 ± 1.52 | 5.19 ± 1.64 |

| Q53 | 0.3384 | - | 6.31 ± 1.12 | 6.37 ± 0.84 |

| Q54 | 0.6747 | - | 3.14 ± 1.85 | 3.08 ± 1.77 |

| Q55 | 0.4762 | - | 3.07 ± 1.83 | 3.03 ± 1.82 |

| Q56 | 0.3196 | - | 5.32 ± 1.63 | 5.26 ± 1.47 |

| Q57 | 0.9173 | - | 4.19 ± 1.81 | 3.71 ± 1.81 |

| Q58 | 0.9898 | - | 6.42 ± 1.02 | 6.47 ± 1 |

| F1 | 0.4459 | - | 548.24 ± 348.32 | 623.21 ± 417.62 |

| F2 | 0.1248 | - | 67.18 ± 86.16 | 80.02 ± 119.36 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Introverted (I) | Extraverted (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | 0.5216 | - | 4.66 ± 0.68 | 4.71 ± 0.62 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0014 | ** | 3.83 ± 1.66 | 4.32 ± 1.33 |

| Q11_TW | 0.0683 | - | 1.52 ± 1.11 | 1.4 ± 1.02 |

| Q11_LI | 0.2555 | - | 1.09 ± 0.39 | 1.18 ± 0.66 |

| Q11_YT | 0.4239 | - | 4.48 ± 0.74 | 4.45 ± 0.71 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0007 | *** | 2 ± 1.58 | 2.51 ± 1.69 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0033 | ** | 2.9 ± 1.76 | 3.41 ± 1.66 |

| Q11_PR | 0.3508 | - | 1.84 ± 1.15 | 1.98 ± 1.26 |

| Q11_WA | 0.1195 | - | 2.26 ± 1.49 | 2.47 ± 1.51 |

| Q11_TL | 0.7750 | - | 1.17 ± 0.54 | 1.18 ± 0.57 |

| Q22_FB | 0.0018 | ** | 3.16 ± 1.35 | 3.57 ± 1.23 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 3.07 ± 1.67 | 3.83 ± 1.46 |

| Q22_TW | 0.5721 | - | 1.33 ± 0.95 | 1.26 ± 0.8 |

| Q22_LI | 0.1003 | - | 1.03 ± 0.22 | 1.09 ± 0.43 |

| Q22_YT | 0.1298 | - | 2.56 ± 1.38 | 2.75 ± 1.41 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0073 | ** | 1.67 ± 1.34 | 2.02 ± 1.54 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0002 | *** | 2 ± 1.46 | 2.55 ± 1.66 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0383 | * | 1.31 ± 0.75 | 1.59 ± 1.13 |

| Q22_WA | 0.1406 | - | 1.64 ± 1.15 | 1.78 ± 1.26 |

| Q22_TL | 0.1726 | - | 1.07 ± 0.41 | 1.09 ± 0.38 |

| Q33_FB | 0.0000 | *** | 1.78 ± 0.9 | 2.16 ± 0.98 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 1.81 ± 0.88 | 2.21 ± 0.97 |

| Q33_TW | 0.2492 | - | 1.13 ± 0.61 | 1.08 ± 0.42 |

| Q33_LI | 0.1238 | - | 1 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.28 |

| Q33_YT | 0.4834 | - | 1.34 ± 0.8 | 1.34 ± 0.7 |

| Q33_TT | 0.2009 | - | 1.11 ± 0.55 | 1.14 ± 0.55 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0004 | *** | 2.2 ± 1.58 | 2.73 ± 1.63 |

| Q33_PR | 0.1011 | - | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.45 |

| Q33_WA | 0.0463 | * | 1.55 ± 1.11 | 1.75 ± 1.23 |

| Q33_TL | 0.2750 | - | 1.03 ± 0.22 | 1.05 ± 0.26 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Introverted (I) | Extraverted (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q41 | 0.6231 | - | 5.22 ± 1.69 | 5.21 ± 1.83 |

| Q42 | 0.0271 | * | 5.35 ± 1.46 | 5.57 ± 1.46 |

| Q43 | 0.0013 | ** | 6.24 ± 1.01 | 6.48 ± 0.9 |

| Q44 | 0.0069 | ** | 4.33 ± 1.66 | 4.75 ± 1.51 |

| Q45 | 0.0064 | ** | 4.48 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 1.63 |

| Q46 | 0.1047 | - | 3.84 ± 1.7 | 4.13 ± 1.86 |

| Q47 | 0.0181 | * | 5.81 ± 1.37 | 6.08 ± 1.19 |

| Q48 | 0.0911 | - | 3.53 ± 1.58 | 3.82 ± 1.58 |

| Q49 | 0.1852 | - | 4.68 ± 1.86 | 4.92 ± 1.79 |

| Q50 | 0.2576 | - | 6.03 ± 1.53 | 6.21 ± 1.31 |

| Q51 | 0.1245 | - | 5.15 ± 1.69 | 5.44 ± 1.46 |

| Q52 | 0.0097 | ** | 5 ± 1.73 | 5.47 ± 1.41 |

| Q53 | 0.0000 | *** | 6.09 ± 1.25 | 6.49 ± 0.87 |

| Q54 | 0.0000 | *** | 2.63 ± 1.72 | 3.48 ± 1.84 |

| Q55 | 0.0002 | *** | 2.7 ± 1.76 | 3.3 ± 1.84 |

| Q56 | 0.9149 | - | 5.25 ± 1.71 | 5.35 ± 1.5 |

| Q57 | 0.0016 | ** | 3.77 ± 1.9 | 4.32 ± 1.73 |

| Q58 | 0.0097 | ** | 6.27 ± 1.22 | 6.57 ± 0.78 |

| F1 | 0.0000 | *** | 433.39 ± 295.47 | 655.85 ± 380.22 |

| F2 | 0.0000 | *** | 50.01 ± 78.99 | 85.05 ± 103.07 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Intuitive (N) | Observant (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | 0.0277 | * | 4.62 ± 0.74 | 4.77 ± 0.52 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0016 | ** | 3.92 ± 1.59 | 4.31 ± 1.36 |

| Q11_TW | 0.1583 | - | 1.5 ± 1.09 | 1.4 ± 1.03 |

| Q11_LI | 0.4115 | - | 1.15 ± 0.56 | 1.13 ± 0.57 |

| Q11_YT | 0.1032 | - | 4.5 ± 0.71 | 4.41 ± 0.73 |

| Q11_TT | 0.3319 | - | 2.24 ± 1.67 | 2.36 ± 1.65 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0013 | ** | 2.94 ± 1.74 | 3.47 ± 1.66 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0194 | * | 2.03 ± 1.25 | 1.79 ± 1.16 |

| Q11_WA | 0.6471 | - | 2.35 ± 1.47 | 2.42 ± 1.54 |

| Q11_TL | 0.1286 | - | 1.2 ± 0.57 | 1.15 ± 0.55 |

| Q22_FB | 0.2213 | - | 3.33 ± 1.31 | 3.47 ± 1.27 |

| Q22_IG | 0.1208 | - | 3.4 ± 1.62 | 3.63 ± 1.57 |

| Q22_TW | 0.2193 | - | 1.33 ± 0.88 | 1.26 ± 0.85 |

| Q22_LI | 0.1498 | - | 1.07 ± 0.36 | 1.05 ± 0.35 |

| Q22_YT | 0.0850 | - | 2.77 ± 1.38 | 2.56 ± 1.42 |

| Q22_TT | 0.4898 | - | 1.83 ± 1.47 | 1.92 ± 1.47 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0995 | - | 2.19 ± 1.56 | 2.45 ± 1.64 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0051 | ** | 1.58 ± 1.09 | 1.34 ± 0.86 |

| Q22_WA | 0.4565 | - | 1.67 ± 1.16 | 1.78 ± 1.27 |

| Q22_TL | 0.0277 | * | 1.12 ± 0.48 | 1.04 ± 0.26 |

| Q33_FB | 0.7089 | - | 2.01 ± 0.97 | 1.98 ± 0.97 |

| Q33_IG | 0.3017 | - | 2.01 ± 0.99 | 2.07 ± 0.91 |

| Q33_TW | 0.8764 | - | 1.12 ± 0.6 | 1.08 ± 0.38 |

| Q33_LI | 0.3368 | - | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 1.03 ± 0.29 |

| Q33_YT | 0.3634 | - | 1.37 ± 0.79 | 1.3 ± 0.68 |

| Q33_TT | 0.5364 | - | 1.14 ± 0.59 | 1.11 ± 0.51 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0645 | - | 2.37 ± 1.61 | 2.65 ± 1.64 |

| Q33_PR | 0.1363 | - | 1.1 ± 0.48 | 1.03 ± 0.22 |

| Q33_WA | 0.3455 | - | 1.6 ± 1.13 | 1.73 ± 1.24 |

| Q33_TL | 0.1640 | - | 1.06 ± 0.29 | 1.02 ± 0.18 |

| Variable | p-value | Significance level | Thinking (T) | Feeling (F) |

| Q11_FB | 0.4094 | - | 4.75 ± 0.53 | 4.67 ± 0.69 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0851 | - | 4.01 ± 1.49 | 4.15 ± 1.5 |

| Q11_TW | 0.3013 | - | 1.39 ± 1 | 1.47 ± 1.09 |

| Q11_LI | 0.0403 | * | 1.26 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.43 |

| Q11_YT | 0.0647 | - | 4.54 ± 0.7 | 4.43 ± 0.73 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0060 | ** | 1.99 ± 1.56 | 2.42 ± 1.68 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0003 | *** | 2.74 ± 1.69 | 3.37 ± 1.7 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0007 | *** | 1.64 ± 1.11 | 2.03 ± 1.24 |

| Q11_WA | 0.6566 | - | 2.44 ± 1.54 | 2.36 ± 1.49 |

| Q11_TL | 0.6352 | - | 1.15 ± 0.47 | 1.19 ± 0.59 |

| Q22_FB | 0.3132 | - | 3.5 ± 1.25 | 3.35 ± 1.31 |

| Q22_IG | 0.1322 | - | 3.34 ± 1.63 | 3.58 ± 1.58 |

| Q22_TW | 0.5754 | - | 1.22 ± 0.65 | 1.33 ± 0.94 |

| Q22_LI | 0.0211 | * | 1.14 ± 0.58 | 1.03 ± 0.2 |

| Q22_YT | 0.3691 | - | 2.75 ± 1.37 | 2.64 ± 1.42 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0512 | - | 1.67 ± 1.35 | 1.95 ± 1.51 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.84 ± 1.39 | 2.5 ± 1.64 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0764 | - | 1.34 ± 0.88 | 1.52 ± 1.04 |

| Q22_WA | 0.6709 | - | 1.69 ± 1.24 | 1.73 ± 1.21 |

| Q22_TL | 0.4011 | - | 1.06 ± 0.32 | 1.09 ± 0.42 |

| Q33_FB | 0.2663 | - | 2.13 ± 1.11 | 1.94 ± 0.9 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0494 | * | 1.91 ± 0.93 | 2.09 ± 0.96 |

| Q33_TW | 0.1831 | - | 1.05 ± 0.33 | 1.12 ± 0.56 |

| Q33_LI | 0.0114 | * | 1.07 ± 0.39 | 1.01 ± 0.08 |

| Q33_YT | 0.0508 | - | 1.43 ± 0.79 | 1.3 ± 0.72 |

| Q33_TT | 0.9223 | - | 1.13 ± 0.6 | 1.12 ± 0.54 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.99 ± 1.36 | 2.71 ± 1.68 |

| Q33_PR | 0.3033 | - | 1.03 ± 0.21 | 1.08 ± 0.43 |

| Q33_WA | 0.8729 | - | 1.68 ± 1.25 | 1.65 ± 1.16 |

| Q33_TL | 0.5454 | - | 1.03 ± 0.21 | 1.04 ± 0.26 |

| Variable | p-value | Significance level | Prospecting (P) | Judging (J) |

| Q11_FB | 0.2534 | - | 4.72 ± 0.64 | 4.67 ± 0.65 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0224 | * | 3.99 ± 1.5 | 4.18 ± 1.5 |

| Q11_TW | 0.4300 | - | 1.48 ± 1.08 | 1.43 ± 1.05 |

| Q11_LI | 0.2510 | - | 1.16 ± 0.56 | 1.13 ± 0.57 |

| Q11_YT | 0.4183 | - | 4.48 ± 0.72 | 4.45 ± 0.72 |

| Q11_TT | 0.6541 | - | 2.24 ± 1.65 | 2.33 ± 1.66 |

| Q11_SC | 0.8990 | - | 3.16 ± 1.75 | 3.2 ± 1.7 |

| Q11_PR | 0.3686 | - | 1.85 ± 1.17 | 1.96 ± 1.24 |

| Q11_WA | 0.0084 | ** | 2.15 ± 1.42 | 2.53 ± 1.54 |

| Q11_TL | 0.4896 | - | 1.15 ± 0.47 | 1.2 ± 0.61 |

| Q22_FB | 0.7678 | - | 3.41 ± 1.32 | 3.39 ± 1.28 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0526 | - | 3.33 ± 1.63 | 3.62 ± 1.57 |

| Q22_TW | 0.7662 | - | 1.3 ± 0.86 | 1.29 ± 0.87 |

| Q22_LI | 0.2411 | - | 1.08 ± 0.4 | 1.05 ± 0.32 |

| Q22_YT | 0.4760 | - | 2.72 ± 1.39 | 2.64 ± 1.41 |

| Q22_TT | 0.5817 | - | 1.93 ± 1.53 | 1.84 ± 1.43 |

| Q22_SC | 0.6826 | - | 2.26 ± 1.56 | 2.35 ± 1.62 |

| Q22_PR | 0.2347 | - | 1.39 ± 0.91 | 1.52 ± 1.04 |

| Q22_WA | 0.7809 | - | 1.66 ± 1.12 | 1.76 ± 1.27 |

| Q22_TL | 0.3074 | - | 1.07 ± 0.34 | 1.1 ± 0.42 |

| Q33_FB | 0.1856 | - | 2.05 ± 0.96 | 1.96 ± 0.97 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0699 | - | 1.92 ± 0.86 | 2.11 ± 1 |

| Q33_TW | 0.2917 | - | 1.1 ± 0.46 | 1.1 ± 0.54 |

| Q33_LI | 0.5576 | - | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.27 |

| Q33_YT | 0.8528 | - | 1.37 ± 0.83 | 1.32 ± 0.68 |

| Q33_TT | 0.8293 | - | 1.12 ± 0.51 | 1.13 ± 0.58 |

| Q33_SC | 0.3330 | - | 2.43 ± 1.63 | 2.55 ± 1.63 |

| Q33_PR | 0.0041 | ** | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.49 |

| Q33_WA | 0.2851 | - | 1.56 ± 1.08 | 1.72 ± 1.24 |

| Q33_TL | 0.7959 | - | 1.04 ± 0.24 | 1.04 ± 0.25 |

References

- Hussain, W. Role of social media in COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Front. Sci. 2020, 4, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, R.J.; Sauer, M.; Ali, J.; Bernstein, J.; Wahl, B.; Barnhill, A.; Labrique, A. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e277–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabity-Grover, T.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Thatcher, J.B. Inside out and outside in: How the COVID-19 pandemic affects self-disclosure on social media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahni, H.; Sharma, H. Role of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: Beneficial, destructive, or reconstructive? Int. J. Acad. Med. 2020, 6, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A.; Gupta, L. Social media in the times of COVID-19. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 26, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Basu, T. The Coronavirus Is the First True Social-Media “Infodemic”. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/615184/the-coronavirus-is-the-first-true-social-media-infodemic (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Kaya, T. The changes in the effects of social media use of cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Sarkar, T.; Khan, S.H.; Mostofa Kamal, A.-H.; Hasan, S.M.M.; Kabir, A.; Yeasmin, D.; Islam, M.A.; Amin Chowdhury, K.I.; Anwar, K.S.; et al. COVID-19–related infodemic and its impact on public health: A global social media analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mazumder, H. Impact of rumors and misinformation on COVID-19 in social media. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2020, 53, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, K.-F.; Chen, M.; Shia, B.-C.; Wu, S.-Y. Prediction of number of cases of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) using social media search index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.R.; Murad, H.R. The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: Online questionnaire study. J. Med. Int. Res. 2020, 22, e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircaburun, K.; Alhabash, S.; Tosuntaş, Ş.B.; Griffiths, M.D. Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the big five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. Digital 2020: July Global Statshot. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-july-global-statshot (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Clement, J. Social Media—Statistics & Facts. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Fan, W.; Gordon, M.D. The power of social media analytics. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A. Social Media Usage: 2005–2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Silver, L.; Huang, C.; Taylor, K. In emerging economies, smartphone and social media users have broader social networks. Pew Res. Cent. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2019/08/Pew-Research-Center_Emerging-Economies-Smartphone-Social-Media-Users-Have-Broader-Social-Networks-Report_2019-08-22.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Correa, T.; Hinsley, A.W.; de Zúñiga, H.G. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgüven, N.; Mucan, B. The relationship between personality traits and social media use. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2013, 41, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnadi, G.; Sitaraman, G.; Sushmita, S.; Celli, F.; Kosinski, M.; Stillwell, D.; Davalos, S.; Moens, M.-F.; De Cock, M. Computational personality recognition in social media. User Model. User Adap. Inter. 2016, 26, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbeck, J.; Robles, C.; Turner, K. Predicting personality with social media. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI EA ’11, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; ACM Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Preotiuc-Pietro, D.; Samani, Z.R.; Moghaddam, M.E.; Ungar, L. Analyzing personality through social media profile picture choice. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cologne, Germany, 17–20 May 2016; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R.A.; Guadagno, R.E. My avatar and me—gender and personality predictors of avatar-self discrepancy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscanell, N.L.; Guadagno, R.E. Make new friends or keep the old: Gender and personality differences in social networking use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzum, M.B. Examining the relationship to gender and personality on the purpose of facebook usage of turkish university students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Rowe, M.; Batey, M.; Lee, A. A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, H.A.; Eichstaedt, J.C.; Kern, M.L.; Dziurzynski, L.; Ramones, S.M.; Agrawal, M.; Shah, A.; Kosinski, M.; Stillwell, D.; Seligman, M.E.P.; et al. Personality, gender, and age in the language of social media: The open-vocabulary approach. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Lerman, K.; Ferrara, E. Tracking social media discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus twitter data set. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020, 6, e19273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Preet, R.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Padilla, D.A.; Tortolero-Blanco, L. Social media influence in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. braz j urol 2020, 46, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollett, S.; Rivers, C. Social media and the new world of scientific communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2184–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yu, X.; Xu, H. Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports-13. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Naeem, M. Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of Covid-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algharabat, R.; Rana, N.P.; Alalwan, A.A.; Baabdullah, A.; Gupta, A. Investigating the antecedents of customer brand engagement and consumer-based brand equity in social media. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Ling, J.; Cheah, J.H. Editorial: It will go away!? Pandemic crisis and business in Asia. AJBR 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NERIS. Analytics Limited. 16Personality—Personal Test. Available online: https://www.16personalities.com/articles/our-theory (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Swani, K.; Milne, G.R. Evaluating facebook brand content popularity for service versus goods offerings. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmezoz, K.; Ugur, O.; Diri, B. MBTI personality prediction With machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Gaziantep, Turkey, 5–7 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gonzalez, H.G.; Nunez-Varela, A.; Martinez-Perez, F.E.; Nava-Munoz, S.E.; David Arjona-Villicana, P.; Castillo-Barrera, F.E.; Munoz-Arteaga, J. Investigating the effects of personality on software design in a higher education setting through an experiment. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Conference in Software Engineering Research and Innovation (CONISOFT), San Luis Potosí, Mexico, 24–26 October 2018; pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, S.; Brotherton, K.; Um, D.; Park, J. Identification of speech characteristics to distinguish human personality of introversive and extroversive male groups. IJERPH 2020, 17, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Central Statistical Office of Poland. Higher Education in the 2018/2019 Academic Year. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/szkolnictwo-wyzsze-w-roku-akademickim-20182019-wyniki-wstepne,8,6.html (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Cho, M.; Auger, G.A. Extrovert and engaged? Exploring the connection between personality and involvement of stakeholders and the perceived relationship investment of nonprofit organizations. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodas, N.O.; Butner, R.; Corley, C. How a user’s personality influences content engagement in social media. In Social Informatics; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Spiro, E., Ahn, Y.-Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2016; Volume 10046, pp. 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, L.; Kiss, A. Social media sentiment analysis based on COVID-19. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2021, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (S1) Sex | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 285 | 60.8% |

| Male | 184 | 39.2% |

| (A1) Age | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| 18–21 | 354 | 75.5% |

| 22–25 | 98 | 20.9% |

| 26–29 | 17 | 3.6% |

| (P2) Personality 2 (own opinion) | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Introvert | 68 | 14.5% |

| Rather Introvert | 68 | 14.5% |

| Both (Ambivert) | 137 | 29.2% |

| Rather Extravert | 97 | 20.7% |

| Extravert | 68 | 14.5% |

| Don’t know/Hard to say | 31 | 6.6% |

| Total | 469 | 100% |

| Social Media | Browsing (Q11) | Reacting (Q22) | Posting (Q33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | Q22_FB | Q33_FB | |

| Q11_IG | Q22_IG | Q33_IG | |

| Q11_TW | Q22_TW | Q33_TW | |

| Q11_LI | Q22_LI | Q33_LI | |

| YouTube | Q11_YT | Q22_YT | Q33_YT |

| TikTok | Q11_TT | Q22_TT | Q33_TT |

| Snapchat | Q11_SC | Q22_SC | Q33_SC |

| Q11_PR | Q22_PR | Q33_PR | |

| Q11_WA | Q22_WA | Q33_WA | |

| Tumblr | Q11_TL | Q22_TL | Q33_TL |

| Id | Short Description |

|---|---|

| Introverts {I} | Prefer solitary activities and tend to be rather sensitive to external stimuli, such as sound, image, or odour. Social interaction exhausts them. |

| Extraverted {E} | Prefer group activities and tend to be more easily excited than Introverts. They get energised by social interaction. |

| Observant {S} | People are very practical and pragmatic. They tend to have well-rooted habits and focus on what is happening. |

| Intuitive {N} | Individuals are very imaginative, open-minded, and curious. They prefer novelty over stability and focus on meanings yet to be uncovered. |

| Thinking {T} | Individuals focus on objectivity and rationality, prioritizing logic over emotions. They tend to hide their feelings and consider efficiency more important than cooperation. |

| Feeling {F} | Individuals are sensitive and emotionally expressive. They are more empathic than Thinking types and promote social harmony and cooperation. |

| Judging {J} | Individuals are decisive, thorough, and highly organised. They value clarity and predictability and prefer structure and planning to spontaneous approaches. |

| Prospecting {P} | Individuals excel at improvising and spotting opportunities. They tend to be flexible, relaxed nonconformists who prefer keeping their options open. |

| Questions | |

|---|---|

| Q60 | How does the pandemic affect your activity level in social media? Has it grown or decreased? |

| C1 | Extra (optional) question: what social platforms will lose popularity over the next year and why? |

| C2 | Extra (optional) question: what social platforms will gain popularity over the next year and why? |

| Type of Activity | Browsing (Q11) | Reacting (Q22) | Posting (Q33) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media | Mean | SD | Mdn | Mean | SD | Mdn | Mean | SD | Mdn |

| Facebook (_FB) | 4.69 | 0.65 | 5 | 3.39 | 1.30 | 4 | 2.00 | 0.97 | 2 |

| Instagram (_IG) | 4.11 | 1.50 | 5 | 3.51 | 1.60 | 4 | 2.04 | 0.95 | 2 |

| Twitter (_TW) | 1.45 | 1.06 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.87 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.51 | 1 |

| LinkedIn (_LI) | 1.14 | 0.57 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.36 | 1 | 1.02 | 0.22 | 1 |

| YouTube (_YT) | 4.46 | 0.72 | 5 | 2.67 | 1.40 | 3 | 1.34 | 0.74 | 1 |

| TikTok (_TT) | 2.30 | 1.66 | 1 | 1.87 | 1.47 | 1 | 1.13 | 0.55 | 1 |

| Snapchat (_SC) | 3.19 | 1.72 | 4 | 2.31 | 1.60 | 1 | 2.50 | 1.63 | 2 |

| Pinterest (_PR) | 1.92 | 1.21 | 1 | 1.47 | 1.00 | 1 | 1.07 | 0.38 | 1 |

| WhatsApp (_WA) | 2.38 | 1.50 | 2 | 1.72 | 1.22 | 1 | 1.66 | 1.18 | 1 |

| Tumblr (_TL) | 1.18 | 0.56 | 1 | 1.08 | 0.39 | 1 | 1.04 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 3.54 ± 1.69 | 4.47 ± 1.24 |

| Q11_YT | 0.0000 | *** | 4.77 ± 0.52 | 4.26 ± 0.76 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.65 ± 1.28 | 2.71 ± 1.74 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 2.76 ± 1.74 | 3.46 ± 1.65 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0000 | *** | 1.26 ± 0.67 | 2.34 ± 1.3 |

| Q11_WA | 0.0034 | ** | 2.13 ± 1.45 | 2.54 ± 1.51 |

| Q11_TL | 0.0000 | *** | 1.07 ± 0.34 | 1.25 ± 0.65 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 2.83 ± 1.68 | 3.94 ± 1.38 |

| Q22_YT | 0.0022 | ** | 2.94 ± 1.52 | 2.49 ± 1.3 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.42 ± 1.11 | 2.16 ± 1.59 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.9 ± 1.45 | 2.58 ± 1.64 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0000 | *** | 1.07 ± 0.31 | 1.73 ± 1.18 |

| Q22_WA | 0.0002 | *** | 1.46 ± 1.01 | 1.89 ± 1.31 |

| Q22_TL | 0.0015 | ** | 1.02 ± 0.21 | 1.12 ± 0.47 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 1.65 ± 0.87 | 2.29 ± 0.92 |

| Q33_YT | 0.0000 | *** | 1.59 ± 0.96 | 1.18 ± 0.5 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 2.02 ± 1.47 | 2.81 ± 1.65 |

| Q33_PR | 0.0008 | *** | 1 ± 0 | 1.11 ± 0.49 |

| Q33_WA | 0.0004 | *** | 1.45 ± 1.04 | 1.8 ± 1.25 |

| Q33_TL | 0.0129 | * | 1.01 ± 0.15 | 1.06 ± 0.29 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q42 | 0.0484 | * | 5.28 ± 1.61 | 5.61 ± 1.34 |

| Q44 | 0.0215 | * | 4.32 ± 1.75 | 4.73 ± 1.45 |

| Q45 | 0.0073 | ** | 4.41 ± 1.86 | 4.92 ± 1.51 |

| Q46 | 0.0309 | * | 3.79 ± 1.93 | 4.15 ± 1.7 |

| Q48 | 0.0027 | ** | 3.42 ± 1.8 | 3.87 ± 1.41 |

| Q53 | 0.0194 | * | 6.21 ± 1.09 | 6.38 ± 1.04 |

| Q54 | 0.0136 | * | 2.91 ± 1.96 | 3.24 ± 1.75 |

| Q57 | 0.0001 | *** | 3.67 ± 1.87 | 4.35 ± 1.74 |

| F1 | 0.0004 | *** | 503.73 ± 386.48 | 597.16 ± 343.11 |

| F2 | 0.3161 | 67.35 ± 94.97 | 71.77 ± 95.18 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Introverted (I) | Extraverted (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_IG | 0.0014 | ** | 3.83 ± 1.66 | 4.32 ± 1.33 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0007 | *** | 2 ± 1.58 | 2.51 ± 1.69 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0033 | ** | 2.9 ± 1.76 | 3.41 ± 1.66 |

| Q22_FB | 0.0018 | ** | 3.16 ± 1.35 | 3.57 ± 1.23 |

| Q22_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 3.07 ± 1.67 | 3.83 ± 1.46 |

| Q22_TT | 0.0073 | ** | 1.67 ± 1.34 | 2.02 ± 1.54 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0002 | *** | 2 ± 1.46 | 2.55 ± 1.66 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0383 | * | 1.31 ± 0.75 | 1.59 ± 1.13 |

| Q33_FB | 0.0000 | *** | 1.78 ± 0.9 | 2.16 ± 0.98 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0000 | *** | 1.81 ± 0.88 | 2.21 ± 0.97 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0004 | *** | 2.2 ± 1.58 | 2.73 ± 1.63 |

| Q33_WA | 0.0463 | * | 1.55 ± 1.11 | 1.75 ± 1.23 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Introverted (I) | Extraverted (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q42 | 0.0271 | * | 5.35 ± 1.46 | 5.57 ± 1.46 |

| Q43 | 0.0013 | ** | 6.24 ± 1.01 | 6.48 ± 0.90 |

| Q44 | 0.0069 | ** | 4.33 ± 1.66 | 4.75 ± 1.51 |

| Q45 | 0.0064 | ** | 4.48 ± 1.7 | 4.90 ± 1.63 |

| Q47 | 0.0181 | * | 5.81 ± 1.37 | 6.08 ± 1.19 |

| Q52 | 0.0097 | ** | 5 ± 1.73 | 5.47 ± 1.41 |

| Q53 | 0.0000 | *** | 6.09 ± 1.25 | 6.49 ± 0.87 |

| Q54 | 0.0000 | *** | 2.63 ± 1.72 | 3.48 ± 1.84 |

| Q55 | 0.0002 | *** | 2.7 ± 1.76 | 3.30 ± 1.84 |

| Q57 | 0.0016 | ** | 3.77 ± 1.9 | 4.32 ± 1.73 |

| Q58 | 0.0097 | ** | 6.27 ± 1.22 | 6.57 ± 0.78 |

| F1 | 0.0000 | *** | 433.39 ± 295.47 | 655.85 ± 380.22 |

| F2 | 0.0000 | *** | 50.01 ± 78.99 | 85.05 ± 103.07 |

| Variable | p-Value | Significance Level | Intuitive (N) | Observant (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11_FB | 0.0277 | * | 4.62 ± 0.74 | 4.77 ± 0.52 |

| Q11_IG | 0.0016 | ** | 3.92 ± 1.59 | 4.31 ± 1.36 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0013 | ** | 2.94 ± 1.74 | 3.47 ± 1.66 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0194 | * | 2.03 ± 1.25 | 1.79 ± 1.16 |

| Q22_PR | 0.0051 | ** | 1.58 ± 1.09 | 1.34 ± 0.86 |

| Q22_TL | 0.0277 | * | 1.12 ± 0.48 | 1.04 ± 0.26 |

| Variable | p-value | Significance level | Thinking (T) | Feeling (F) |

| Q11_LI | 0.0403 | * | 1.26 ± 0.80 | 1.1 ± 0.43 |

| Q11_TT | 0.0060 | ** | 1.99 ± 1.56 | 2.42 ± 1.68 |

| Q11_SC | 0.0003 | *** | 2.74 ± 1.69 | 3.37 ± 1.70 |

| Q11_PR | 0.0007 | *** | 1.64 ± 1.11 | 2.03 ± 1.24 |

| Q22_LI | 0.0211 | * | 1.14 ± 0.58 | 1.03 ± 0.20 |

| Q22_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.84 ± 1.39 | 2.50 ± 1.64 |

| Q33_IG | 0.0494 | * | 1.91 ± 0.93 | 2.09 ± 0.96 |

| Q33_LI | 0.0114 | * | 1.07 ± 0.39 | 1.01 ± 0.08 |

| Q33_SC | 0.0000 | *** | 1.99 ± 1.36 | 2.71 ± 1.68 |

| Variable | p-value | Significance level | Prospecting (P) | Judging (J) |

| Q11_IG | 0.0224 | * | 3.99 ± 1.50 | 4.18 ± 1.50 |

| Q11_WA | 0.0084 | ** | 2.15 ± 1.42 | 2.53 ± 1.54 |

| Q33_PR | 0.0041 | ** | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.49 |

| Group | p-Value | Significance Level | (G1) Mean ± SD | (G2) Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Płec (G1 = M, G2 = F) | 0.2139 | 3.35 ± 0.79 | 3.44 ± 0.78 | |

| PP11 (G1 = I, G2 = E) | 0.0372 | * | 3.31 ± 0.76 | 3.47 ± 0.8 |

| PP12 (G1 = N, G2 = S) | 0.9666 | 3.41 ± 0.78 | 3.39 ± 0.79 | |

| PP13 (G1 = F, G2 = T) | 0.0035 | ** | 3.25 ± 0.7 | 3.47 ± 0.81 |

| PP14 (G1 = J, G2 = P) | 0.2917 | 3.46 ± 0.72 | 3.36 ± 0.82 |

| Social Media | Decrease in Popularity (%) Question C1 | Increase in Popularity (%) Question C2 |

|---|---|---|

| Instagram (IG) | 2% | 50% |

| TikTok (TT) | 10% | 46% |

| Snapchat (SC) | 43% | 2% |

| Facebook (FB) | 37% | 8% |

| Twitter (TW) | 7% | 6% |

| YouTube (YT) | 3% | 5% |

| WhatsApp (WA) | 3% | 3% |

| Discord, Twitch, Vinted, Pinterest, Weverse, Skillshare | - | 1–3% |

| Question C2—What Social Platforms Will Gain Popularity Over the Next Year and Why? | Who * |

|---|---|

| Instagram because people prefer viewing pictures over reading. | Male, 18–21, E,N,F,J |

| Pinterest because it inspires new ideas, passions, and décor adapted to personal preferences. | Female, 18–21, E,S,F,J |

| Skillshare because people started to work on their hobby skills and knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Female, 18–21, I,N,F,J |

| Discord because it is anonymous, free, and works better than Facebook. | Female, 18–21, I,S,F,P |

| TikTok because the youth quickly grows addicted to it. | Female, 18–21, E,N,F,J |

| Instagram because its interface looks nice. | Female, 18–21, I,N,F,J |

| TikTok because it has many silly videos, and people need a distraction at this time (COVID-19). | Female, 18–21, E,N,F,J |

| YouTube because people have nothing to do during COVID-19, and they watch videos. | Male, 18–21, E,N,F,P |

| TikTok because music is a way to handle negative events, also related to COVID-19. Additionally, choreography by a famous influencer drives users to follow trends and boast about it. | Male, 18–21, E,N,F,P |

| TikTok because people started to use it more for entertainment during COVID-19. | Male, 18–21, E,N,F,P |

| Instagram and TikTok. People are lazy. It is easier for them to watch than read. | Female, 22–25, E,N,F,J |

| TikTok because of lots of free time young people have no way of spending and susceptibility to trends. | Male, 22–25, E,N,T,J |

| TikTok because this application is linked to significant creativity. | Female, 18–21, E,N,F,J |

| TikTok because it is the most captivating of all the available applications. | Male, 18–21, E,N,F,J |

| Instagram. Because of COVID-19, ‘life on Instagram’ thrives. Advertisements and discount codes encourage people to buy. Photographs (often idealised) attract new users. | Female, 18–21, E,N,F,P |

| TikTok because one can work on their passions, such as dance or singing, or simply be true self, post silly acts. | Female, 18–21, I,N,F,P |

| Question C1—What Social Platforms Will Lose Popularity Over the Next Year and Why? | Who * |

|---|---|

| Snapchat because fewer and fewer people use it, and the largest creators are withdrawing from it. | Male, ISTJ |

| Facebook because each update brings more usability issues. | Female, INTJ |

| Twitter, because the Twitter community is just celebrities, politicians, and official accounts of brands and organisations. | Male, ENTJ |

| Facebook, because many people move to Instagram. | Male, ENTP |

| Facebook and Snapchat because other platforms take over their functions and become much better. | Female, ESFJ |

| Snapchat because Instagram now offers the same function (stories). | Female, INFJ |

| TikTok because its popularity is temporary (just as was the case of musical.ly). I predict a quick growth and quick fall. | Female, ESFJ |

| Snapchat because it was pushed out by Instagram. | Female, ISFP |

| Facebook because it is an old app and spies on us. | Female, INFJ |

| Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people took to sharing their opinions online, which caused unnecessary disputes. It is also a cause of giving up on Facebook, to get away from toxic people. | Male, ENFP |

| Snapchat because the young generation follows trends, and TikTok has grown its global presence lately (COVID-19). | Female, ENFJ |

| TikTok because of excessive hate against creators. | Male, ISFP |

| YouTube, because of excessive advertising. People will move to Twitch. | Male, ENTJ |

| Facebook, because of lots of worthless content. It is more of a notice board now. Most people use only Messenger. | Female, ENFP |

| Snapchat because it is not updated any more. | Male, ESFJ |

| Facebook, because it has become boring. | Male, INFP |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdonek, D.; Król, K. The Impact of Sex and Personality Traits on Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094793

Zdonek D, Król K. The Impact of Sex and Personality Traits on Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094793

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdonek, Dariusz, and Karol Król. 2021. "The Impact of Sex and Personality Traits on Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094793

APA StyleZdonek, D., & Król, K. (2021). The Impact of Sex and Personality Traits on Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Sustainability, 13(9), 4793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094793