1. Introduction

Who designs cities? For example, who designs a city such as Las Vegas? Rather, who produces Las Vegas in substantial and significant ways? Urban designers? City planners? Policy makers? Private developers? And how is the city produced and reproduced spatially? One dominant historical narrative of urbanism places often-iconic individuals, such as heroic architects (e.g., Le Corbusier), landscape architects (e.g., Frederick Law Olmstead), urban designers (e.g., Andres Duany), and city planners (e.g., Daniel Burnham) at the center as primary actors. However, historians of urbanism such as Spiro Kostof [

1] debunked this persistent myth of the singular actor, who is usually seen as male and white.

The contemporary city, in the context of capitalism and of democracy, is even more complex. While planners in cities such as Las Vegas are supposed to be doing the big-picture thinking, they very rarely do so in truly equitable and democratic ways e.g., [

2]. For example, much of Las Vegas is in fact poorly planned, design and built (e.g., see

Figure 1). Dealing with the persistent precarity of cities is left largely to individual residents to cope with and to navigate, while collective actors such as grassroots organizations, community groups, and, most of all, social and political movements attempt to not only have their voices heard but to actually contribute to the production of urbanism.

Kostof [

1] deftly answered the vital and often critically unexamined question of “Who designs cities?” with a seemingly simple yet profoundly meaningful answer: “Power designs cities.” Thus, the question of the ongoing production and reproduction of contemporary urbanism is better framed via the lens of the spatial political economy. The spatial political economy is a city’s power structure and dynamics, most often seen in the traditional realms of politics and economics but also more widely in social and cultural terms, through which the material city is shaped directly and indirectly. Cuthbert [

3] described the significance of this radical shift from conventional thinking around “urban designers design cities” towards the production of the city in terms of spatial political economy as historically generated ideological processes of reproducing urban space as well as a meta-narrative that incorporates the spatial interests of multiple actors and disciplines.

Such a radical shift provides powerful insights into why, for example, a relatively prosperous city such as Las Vegas, with not one but two well-funded and highly resourced planning departments (i.e., Planning Department of the City of Las Vegas for the area within the strict administrative limits of the central city, and Department of Comprehensive Planning of Clark County for the larger metropolitan region), results in a material city that is spatially inadequate (e.g., largely biased towards cars and against pedestrians, poorly adapted to its climate, lack of transportation choices, fragmented neighborhoods, lack of affordable housing, inadequate public spaces). Some of these are spatial manifestations of more deep-rooted and persistent problems such as urban inequality and urban precarity. In these ways, Las Vegas is reflective of the vast majority of large U.S. cities.

Examining the spatial political economy of a city enables us to not only better understand how cities are actually designed, by whom and for whose benefit e.g., [

2], but also to gain insight into the fact that designing a city implies heavily influencing its urbanism in terms of ongoing and multifaceted processes through practices that intervene in its larger power structures and dynamics, rather than narrowly focusing on it as a finished product through conventions such as master plans, design guidelines, planning regulations, and three-dimensional projects (even though those do matter in such processes). It is through this lens that we can see that traditional institutions and practices such as planning agencies, city councils, private developers and individual urbanists are not only unable to mitigate the vital problem of urban precarity, but also perpetuate it through their private profit-driven practices either explicitly or implicitly in cities such as Las Vegas.

Urban precarity is the socio-economic condition embedded in a city’s urbanism that makes marginalized populations such as the poor, the elderly, immigrants, and women constantly vulnerable to the vicissitudes of political decision-making and economic systems that favor the rich and the well-connected. Precarity is a fundamental, yet usually hidden and often overlooked condition of U.S. urbanism, particularly for those who represent the labor that produces and reproduces the capitalist city. The question, then, is how do those who represent these under-represented people, labor unions, engage with and help shape the underlying spatial political economy of urbanism? This is the question I address in this article.

My research over the past few years on the urbanism of Las Vegas has investigated the ways it reflects and deepens our broader understanding of the spatial production of the contemporary city e.g., [

4,

5]. While mainstream scholars of urbanism have tended to shun Las Vegas as an outlier and an aberration of what a city is and what a city should be, other scholars from different perspectives such as political science, sociology, history and anthropology have found many insightful commonalities. My own research has found some of the same dynamics found in other U.S. cities: how civic boosterism to promote private projects is masqueraded as public benefit, how the design of the city is influenced by economic imperatives and engineering standards rather than design principles, how change in the fabric of the city occurs in fits and starts rather than incrementally, and so forth. The unique contribution of Las Vegas is that as a city of apparent extremes, it renders into clear relief the same or similar dynamics of contemporary urbanism that other U.S. cities, such as New York, Chicago and New Orleans, possess. In this article, when I speak of the “city of Las Vegas,” I mean the larger metropolitan region, which is generally co-terminus with Clark County in the southern part of the state of Nevada in the western United States.

The rest of this article is organized in the following manner. I begin by describing the research method I utilize, which is case study analysis based on a rich trove of empirical evidence gathered from multiple primary and secondary sources and analyzed through a literature review on unions and cities and on unions in Las Vegas. I then describe Las Vegas as a site for analyzing the relationship between unions and cities, which is an ongoing struggle given that in the United States, membership in and influence of unions has been steadily declining and only 11 percent of its workforce is currently unionized. The next section is the main section of the article, as it describes in some detail the Culinary Union and the way its work represents the three main aspects of this analysis: first, the role of organized human labor in the spatial production of the city; second, how its different programs in health, economic opportunities, citizenship, and housing mitigate urban precarity by advocating for the public realm; and third, the many practices it deploys to assert agency in the power dynamics of the city. The article concludes with insights and implications for urban practice.

2. Research Method

In this research, I primarily deploy the case study method. There has been excellent research conducted by Flyvbjerg e.g., [

6] and others challenging conventional views and outdated constraints of utilizing case studies as a basis for a more general understanding of phenomena, such as crafting alternative narratives regarding the spatial production of cities. The first advantage of the case study method is that case studies are understood within their specific contexts, which is true of all phenomena regarding cities. Context is not only historical and geographical, but also political-economic (e.g., how power is structured and how decisions are made, with what impacts), as I highlight vividly in this article. A second advantage of the case study method is that it can consist of a richly described narrative, with actors, decisions, sequences of events and outcomes, which is how I have tried to craft an argument of the relationship between the Culinary Union and the urbanism of Las Vegas. A third advantage of this method is what I call an “illuminating case study,” which I define as a case study analysis that not only helps us to understand a particular phenomenon but also shines a light on similar phenomena in other cities. Thus, the specific role of the Culinary Union in the urbanism of Las Vegas helps us to not only become curious about how labor unions have helped shape other cities, but also how and why their roles and effectiveness have differed in those cities.

For the case study, I relied on primary sources such as interviews with key actors including Geoconda Arguello-Kline, an immigrant from Nicaragua, former hotel housekeeper and as Secretary-Treasurer, leader of the Culinary Union; Bethany Khan, first-generation daughter of immigrants and Director of Communications Digital Strategy for the Culinary Union; Ruben Garcia, Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Workplace Law Program at the University of Nevada who has worked with unions as well as conducted research about them; and Robert Summerfield, Director of Planning for the City of Las Vegas, who has been both an antagonist and a partner to labor unions in the city. I also relied on portions of lengthy general interviews documented by the Oral History Center at the University of Nevada, especially of D. Taylor, the former leader of the Culinary Union in Las Vegas and currently leader of the national union, UNITE HERE, in Washington DC., the parent organization of the Culinary Union. Another primary source I relied on was direct observation, including visiting the various sites in the city that are part of this research (e.g., headquarters of the Culinary Union, Culinary Academy training facility), speaking to those who were directly involved in the various programs, and documenting them through photographs. Since the article is about the analysis of the spatial production of urbanism, I felt that it was essential to visually explore the spatialities of the union’s interventions, in terms of their locations, their material forms, and so forth.

Another major source of information for this research was newspapers. Newspapers have multiple benefits as sources, especially when the research is within a specific local context such as the city of Las Vegas: understanding how people viewed a program, process or event when it happened, understanding multiple points of view about an issue, allowing one to trace the evolution of a program or process over time, identifying key actors in a process, and providing a glimpse into the time period when those events occurred. As a follow-up, I consulted with newspaper reporters about their observations about how events evolved over a particular time period (e.g., 5–10 years) and about the various sources they interviewed for their reporting, especially since a good journalist tends to rely on multiple sources and differing perspectives for their reports. In general, the local media (e.g., newspapers, television stations, prominent websites) provide one measure of how key actors in urbanism (e.g., labor unions, casinos and hotels, local government) are perceived within their context. Therefore, newspapers can provide a rich source of knowledge, especially for qualitative types of research and if they are placed within a larger context and viewed with a critical eye (e.g., if the newspaper has its own perspective, such as serving as boosters for the local hospitality industry).

The analysis was driven by the intersection of extensive empirical evidence gathered from multiple sources, including the ones described above, and a literature review on cities and unions e.g., [

7] and unions in Las Vegas e.g., [

8]. In terms of understanding the different ways in which unions affect the urbanism of Las Vegas, I drew from previous research that examined urbanism not only as a purely aesthetic or technical practice, but as a longer-term process that is part and parcel of a city’s spatial political economy e.g., [

3]. Spatial political economy enables an analytical narrative of urbanism that is both deeper (e.g., by examining how power is wielded in the shaping of the city) and broader (e.g., by examining how such power is structured politically and economically) than conventional ones. In this manner, what is revealed to us is that beyond conventional power brokers such as political leaders and professional practitioners lie a vast array of actors and movements than can and do “design” (i.e., shape spatial production) in ways that can be more democratic and equitable.

3. Unions and Cities: Las Vegas as Site of Analysis

American labor unions have been declining in membership and influence, paralleled by reduced interest in studying them by scholars and practitioners, especially in design and urbanism. Union representation in the United States is 11 percent of combined public and private sector employment, totaling 14.8 million workers, compared to 90 percent of the total workforce in Iceland, which has the highest percentage in the world [

9]. Despite their weaknesses, labor unions in the post-World War II period have continued to represent a major force for social reform. Most notably, they have remained the key vehicle by which the working poor might pass from silence to an active voice in U.S. public life. Unions are important for giving voice to those who produce and reproduce the city by mitigating the many precarities of urban life. Organized labor’s daily engagement with the life of the city is more complex than commonly recognized [

7]. This includes in urbanism, which I have previously defined as city-design-and-building processes and their spatial products [

10].

Las Vegas has impressive union density rates, particularly in services. Union density is the ratio of wage and salary earners that are labor union members to the total number of wage and salary earners in the economy. Las Vegas’s union density is the result of three major unionization efforts in casinos, hotels and resorts, in construction, and in hospitals. Las Vegas has a total union membership of 15.7% percent of workers, including 12.5% of private workers and 39.6% of public workers [

11]. In 1998, after the longest labor action in American history (see section on strikes later in the article), the Culinary Union, Las Vegas’s most powerful, won an enormous victory not only over the Frontier Hotel, but also in the ongoing contest between labor and management in what became the most unionized city in the United States [

12]( p.p. 63–68). In the process, the Union consolidated Las Vegas’s place as one of the last places in American society where so-called “unskilled” and “semi-skilled” workers can earn a middle-class wage and be able to create the prosperity that was once the hallmark of the unionized working class.

While most cities’ economies have been restructured into smaller units of production, contemporary Las Vegas has tended to be dominated by a handful of companies that employ a large percentage of the local workforce and wield enormous power in local life. At the other end, the base of Las Vegas’ postindustrial job pyramid is the labor of women [

13], with the two of the largest job categories in its economy being servers (also known as waitresses) and housekeepers (also known as maids who clean hotel rooms). In addition, data from 2018 show that 72% of service workers and 79% of laborers in the Las Vegas economy are from minority (i.e., non-white) backgrounds [

14].

The success of the unionized workforce in Las Vegas may be perceived as an anomaly because to an individual, there is not always a clear-cut economic benefit from belonging to the union. To want to belong to a union, a worker has to understand the larger picture, to understand that the presence of the union sets the pay even in non-union places of employment, to know that the union leads to better working conditions in the labor-intensive and physically difficult service industry, to see that the union leads to seniority, consistency in hours per week, and protection from arbitrary workplace rules. On the other hand, the corporate owners of the casinos, hotels and resorts in Las Vegas need a well-trained and stable work force, because these are the workers who are the everyday public face of their operations, as casino dealers, restaurant servers and bartenders, and housekeepers. In addition, corporate strategies can be particularly effective in firms that rely on a good public image, which may seem counter-intuitive in a city often known as “Sin City.” However, Las Vegas casino owners are vulnerable to corporate campaign tactics since they constantly need to sell themselves, not only to investors and visiting tourists, but also to the gambling regulatory bodies which license the casinos. For example, casino owners need to be cognizant of the possible consequences of poor labor policies while setting salaries, benefits and working conditions, and changing regulations governing such as working conditions in the gambling industry [

15].

At the same time, unions have fought to protect the interests of the casino industry, because it is the primary reason for the union’s existence and the primary source of most their members’ incomes. “For instance, the unions have lobbied extensively at the federal level to get the federal government to finance an expansion of Interstate 15 highway, which connects Las Vegas to Los Angeles, and is a key component of the city’s tourist market” [

8](p.1697). Unions in Las Vegas have adopted a symbiotic relationship with the casino and hospitality sectors because they know that under current conditions, the sectors’ economic well-being is directly related to their members’ economic well-being and that the sectors’ future growth implies the unions’ future growth and members’ future job security and benefits. This leads to a relationship that is at once both contentious and cooperative.

The relationships between unions and cities are multifaceted and complex [

7], and very much worth unpacking because they yield powerful insights into far more democratic types of urban practices. First of all, unions are urban because they are in cities. By cities, I mean metropolitan regions in which central cities and suburban areas intertwine economically and socially. Second, unions are urban because they link together the separate spheres of the everyday lives of the people they seek to organize (e.g., the workplace, the community, the home, the streets) and the different ways in which people experience their class position (e.g., by gender, race, level of skill, citizenship status). Through different actions, unions can actually help to create spatialized networks of what may otherwise seem to be discrete activities in different parts of the city (e.g., connecting issues of employment with issues of housing and health facilities). Third, unions are urban because they negotiate how cities evolve and how they are governed by their residents, especially union members and their families, and by proxy and through ripple effects, those in similar workplaces but non-unionized situations. Fourth, the urban suggests a concentration of space at multiple scales (e.g., buildings, streets and open spaces, neighborhoods, cities, regions) and thereby a concentration of actors and actions in cooperation and conflict. Fifth, unions increasingly act in cooperation with or in opposition to other actors who are in the same geographical as well as political and economic spaces. To further unpack these relationships, I now focus on three aspects, using the Culinary Union and its contributions to the urbanism of Las Vegas as the site of analysis: how the spatial production and reproduction of the city is an ongoing product of organized labor, how the union helps mitigate urban precarity by advocating for the public realm in multiple ways, and what influential roles the union plays in the power structures and dynamics of urbanism.

4. Culinary Union and the Urbanism of Las Vegas

Since it was first chartered in 1935, the Culinary Workers Union Local 226 of the national union UNITE HERE (which is the result of the merger of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees, or UNITE, and the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union, or HERE) has fought an endless succession of labor struggles to unionize the growing hospitality industry of Las Vegas (see

Figure 2). Henceforth, I will refer to the Culinary Workers Union Local 226 as simply the “Culinary Union” in this article. Currently, the union has 50,007 active members from 178 countries [

16]. Thanks largely to the efforts of the Culinary Union, the average worker in the largest and most well-known casinos, hotels and resorts and their hybrids (i.e., combined casino-hotel-resorts) on the famed “Las Vegas Strip” (i.e., South Las Vegas Boulevard) earns an average of USD 23 per hour [

17]. In 2018, the average wage of housekeepers was USD 15.50 per hour and the average wage of servers was USD 12.50 per hour, in contrast with the minimum wage in the state of Nevada at the time of USD 7.25 per hour [

18]. According to one study, hotel workers earned 23–31% more in Las Vegas as compared to the sector’s average in the rest of the country [

15].

4.1. Role of Organized labor in the Spatial Production of the City

The problem with postmodern narratives about contemporary urbanism, including the seminal book

Learning from Las Vegas [

19], is that they tend to ignore spatial political economy by accepting the material form of a city as given, instead of investigating how it is actively produced through human labor and the practices that constitute that labor process [

8]. In this counter-narrative, while casino and hotel developers do exert more influence over the production of Las Vegas due to their economic and political power, they also depend on labor not only for the construction of the hotel, casino and resort complexes but also for their subsequent day-to-day operations. Such labor is essential for the successful operation of the hospitality industry, which gives organized labor greater agency in the spatial production and reproduction of Las Vegas. Thus, urbanism is as much a verb as a noun [

10] in terms of how it is produced as much as what is produced, and the city is thereby ongoingly produced and reproduced through practices and processes of actual human labor, further organized and empowered through unions. Human labor is essential in the spatial production of Las Vegas, in terms of construction of projects, in the complex backroom operations to make facilities run, and as the first line of contact and public face for their hospitality operations for visitors.

4.1.1. Organized Labor: Shaping Economic Landscapes

A consideration of labor unions as urbanists thereby points to the fact that the economic landscapes of the material city are shaped not only by business investment decisions, but also by the human labor of the working class. This insight is especially empowering for better understanding cities, because it says that the decisions, actions and organizations of the working class matter to how our society is organized [

7]. For example, by employing workers around the clock in three shifts, casinos in Las Vegas are able to conform to union requirements for an 8-hour workday while enabling the casinos to earn round-the-clock revenue. Other businesses, such as dry cleaners, fast-food restaurants, and grocery stores, also benefit from the 24-hour lifestyle, with many of them remaining open all night as well [

20]. In addition, the rest of the citizens of Las Vegas benefit through multiple ripple effects through an estimated “

$1 million per day paid out to services and products” [

21]. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the opening of new casino-hotel-resorts increased the demand for workers in Las Vegas and because of this, business owners saw the Culinary Union as an important partner. At the time, the lack of labor meant that the union became a kind of human resources department by recruiting workers for cooperative casino owners such as Bill Bennett and Steve Wynn [

12].

4.1.2. Organized Labor: Precarity

At the same time, lower-wage workers tend to live in a constant state of precarity, with persistent insecurity with regard to the lack of stable income and employment. For these such workers, the demand for higher wages and safe working conditions cannot be divorced from the need to address disparities in wealth, health, housing, and education that are tied to race, gender, class, geography, and immigration status [

22]. Currently, nearly all of the corporate-owned casinos, hotels and resorts on the Las Vegas Strip have been unionized, and the representation of the Union has grown from 18,000 workers in the 1980s to well over 50,000 workers in the late 2010s. One of the primary reasons for this growth is effective practices that contribute to the vitality of the larger public realm of the city (described in more detail further in this article), such as “when unions bring their demands in line with the needs of the community, thereby benefiting not only union workers but all similarly situated workers across the various geographies and demographics” and when they push “boundaries of what it means to be in a union and spurs worker movements to have significant impact on housing, education funding, health care, the environment, and other areas” [

22](pp. 519–522). The Culinary Union in Las Vegas is an exemplar of such practices.

4.1.3. Organized Labor: Space Matters

At this point, it is helpful to clarify the meaning of “space” in spatial production and the role of human labor within it. While conventional notions of designing cities tend to focus on the three-dimensional form of spatial products e.g., [

23], scholars have been challenging these notions to include ideas of use and management in addition to spatial form and aesthetics [

24], that design occurs within a larger spatial political economy e.g., [

3], and processes of design that are in fact creative political acts resulting in fundamental urban transformations e.g., [

10]. In these ways, space matters in the arena of labor–capital relations and the actions of workers shape the landscape of the world’s political and economic geographies [

25]. Contrary to the neoliberal assumption that only capital drives the global economy and that workers are simply another factor of production; the geography of capitalism is in fact a contested terrain in which workers are the concrete manifestations of human labor. To gain a more complete understanding of the processes of urbanism, we must account for the ways in which workers seek the conditions that ensure their own well-being.

Spatially, the size and urban density of cities matters significantly to the success of urban labor strategies [

7]. This is due to the way in which labor has come to rely on a multiplicity of different actors and forms of coordination in more dense urban spaces. For example, labor’s rent gap strategies are usually possible in large cities and they work best in downtown or higher-density locations, where the largest profits are to be made (as is the case of the Las Vegas Strip) or which are often more heavily regulated. In an industry that is highly segmented by price and quality of service, the Culinary Union has targeted its organizing efforts on the higher-priced casinos and mid-priced full-service properties in urban areas (e.g., casinos that include hotels and resorts), rather than the lower-priced budget establishments in the suburbs or road-side locations [

26]. Therefore, by some estimates, over 90% of the Class A luxury casinos, hotels and resorts and 70% of the local casinos marketed to local residents are unionized [

8](p. 1690).

4.1.4. Organized Labor: Strategic Interventions

The targeting of the most high-profile and resource-rich casinos by the union is a form of strategic urban practice, especially since such developments tend to focus on quality of services that are highly dependent on relatively well-trained human labor. In general, such types of developments (e.g., casinos, hotels, resorts, stadiums, office complexes, entertainment districts, shopping centers) constitute the metaphorical “frontstage” of cities by benefitting from their larger scales, prominent locations and quite commonly, public subsidies. In addition, due to the advantages of spatial proximity (e.g., concentration of casinos on the Las Vegas Strip or on Fremont Street in downtown), there is higher visibility for overt political actions such as protests. Such spatial proximity enables the union to deploy targeted interventions to build up critical mass to effect more systemic change.

4.1.5. Organized Labor: Planning and Development

Another spatial aspect of unions as urbanists is the relationship with formal planning and development in Las Vegas. The Culinary Union directly intervenes with the growth of the urban form when they feel that an injustice will take place against workers in the operations of a development. For example, the new City Hall building was staunchly opposed by the Culinary Union, who viewed it as a mismanagement of public funds towards a project that neither consulted the public nor guaranteed living wage salaries and unionized benefits. Chris Bohner, the Culinary Union’s research director, told the City Council of Las Vegas that “it was irresponsible to pursue a new city hall building when the city is cutting its budget to make ends meet and seeking to revisit union contracts to slow the growth of personnel spending” cited in [

27]. The union engaged in several types of urban practices, such as protests and a lawsuit. Consequently, in 2009, the union and the City of Las Vegas reached an agreement related to the Union’s involvement in development projects. The memorandum of understanding stated that gambling-related hospitality projects where there are public financial and proprietary interests must seek an agreement with an appropriate union. In return, the union agreed to refrain from opposing new projects in the redevelopment area and stay neutral on redevelopment-related state legislation. They also agreed to create a citizens advisory committee for the city’s Redevelopment Agency, to focus future redevelopment on neighborhoods at risk of decay, and to conduct a living-wage study [

28,

29,

30].

4.2. From Precarity to Public Realm

The Culinary Union is directly engaged everyday with the public realm of the city. The public realm is a much more potent and robust concept than usual discussions of public space. Public space is a vital aspect of urbanism, but it is most often viewed by designers as primarily a defined space (e.g., a square or a park) that contains various activities. The public realm, on the other hand, recognizes the spatiality of urbanism but stretches far beyond into interconnected spatial networks that traverse different neighborhoods to connect the city and into vital aspects of control of space and governance. The public realm is also about the way different nominally private aspects of everyday life in the city (e.g., home, work, education, transportation) link up in various ways to create a collective dynamic. In other words, the most effective labor unions in cities tend to fully engage with the public realm of the city, and one of the best exemplars in the United States is the Culinary Union.

The union advocates for the public realm in several ways, particularly in the absence of any serious advocacy or stewardship of it by planning agencies or local governments. First, it does so by asserting its right to occupy public space as a site for protest. Second, it engages politically (e.g., through advocacy for particular issues and candidates) beyond narrow interests and private concerns (e.g., for immigrants, housing, healthcare, citizenship). Third, it links together the separate spheres of the everyday lives of the people it seeks to organize (the workplace, the community, the home, the streets, and the public sphere) and the different ways in which people experience their class position (gender, race, citizenship status, high skill/low skill, producer, and consumer). By advocating for the public realm in these ways, the union helps to mitigate precarity for their members and their families, which is an estimated 145,000 citizens in the case of Las Vegas. Thus, “in cities where organized labor has achieved some measure of political power and policy influence, unions often find themselves in the role of effectively contesting urban inequality” [

7](p. 15). I will now illustrate these points by describing how the Culinary Union advocates for and enhances the public realm in Las Vegas through initiatives such as health facilities and services, job training facilities and economic opportunities, active citizenship at the local and national levels, and access to decent housing.

4.2.1. Public Realm: Health

“The Culinary Union is paying close attention to rising health care costs and we continue to be involved in issues that affect over 145,000 Culinary Health Fund participants—including keeping quality healthcare affordable and accessible,” said Geoconda Arguello-Kline cited in [

31]. In order to do this, the union established a health fund, a pharmacy and health center [

32]. The Health Fund, founded in the 1960s, provides health care benefits to members and their families, who have no monthly premium payments and free generic prescription drugs, low copays, and full-coverage benefits including mental health counseling and drug and alcohol treatment. Moreover, the Health Fund was the first health plan in Nevada to recognize and provide benefits to same-sex domestic partners, 17 years before gay marriage was legal in the state. The Health Fund also covers medications and counselling services associated with HIV/AIDS.

The Culinary Pharmacy, founded in 2001, has become the busiest pharmacy in Nevada and all prescriptions of low-cost generic drugs are dispensed free to Culinary Union members and their families. Casino-hotel-resort companies such as Caesars Entertainment complemented this initiative by opening their own in-house pharmacy for union and non-union casino workers. The Culinary Health Center is for use by Health Fund participants, and offers urgent, primary, pediatric, dental and eye care services, as well as a pharmacy and a library. In 2017, a new 59,000-square-foot two-story Health Center opened in East Valley, replacing a previous center on the site. The project was funded by the Health Fund and the area was chosen because over 40,000 union members live within a close radius of the facility [

33].

4.2.2. Public Realm: Economic Opportunities

In 1993, the union negotiated a multi-employer training fund, one of the first in the service sector, to provide a jointly governed training program in all of the culinary trades in Las Vegas [

8]. The program also receives federal, state and local grants to provide training to people who are not members of the union. The resulting Culinary Academy of Las Vegas is a nationally recognized model of labor and management cooperation between the Culinary and Bartenders Unions and 28 casinos, hotels and resorts on the Las Vegas Strip. The vision of the Culinary Academy is to significantly reduce poverty and unemployment by providing vocational skills to youth, adults, and displaced workers [

32]. The primary goals of the Culinary Academy are job training and career opportunities to enable economic and social mobility, as described by Arguello-Kline: “If I (want to) move to another classification, I can prepare myself, I can go to the Culinary Training Academy and prepare myself to be a cook, to be a food server, and then receive the training (to) move to another classification and see (my) job as a career” [

34].

The Culinary Academy provides free hospitality training to qualified workers as part of their union benefits. Flexible scheduling enables people to complete the training while working, thereby refreshing and upgrading their skills to advance in their careers. Classes includes baker’s helper, bar apprentice, bar porter, bus person, food server, fountain worker, guest room attendant, house person utility, professional cook, sommelier, steward, and wine server [

32]. After the global financial crisis in 2008, companies started paying more attention to quality customer service to attract and retain more guests. “There’s more of a premium being placed on customer service,” said Monica Ford, Vice President of Training and Development at the Academy. “It has long taught the mechanics of hospitality jobs to legions of workers, including how to make beds, cook omelets and serve drinks. But lately, at the behest of local hotels, the academy has been putting a greater emphasis on basic customer service skills, such as addressing guests and being cordial” cited in [

35]. The Culinary Academy has trained over 40,000 workers in their high-quality programs (e.g., see

Figure 3).

4.2.3. Public Realm: Citizenship

The Culinary Union’s Citizenship Project, created in 2001, has helped over 16,000 workers through the entire process, including application and preparation for the exam, to become U.S. citizens and new voters [

36]. This is the embodiment of the public realm par excellence because it substantively embraces the philosophy that the city—and the country it is situated in—belongs to everyone. In other words, everyone has the right to live, work and produce the city. The Culinary Union’s vision is thus bold and visionary. This is quite unique since their existence and phenomenal growth is intertwined with the traditionally top-down and exploitative industries of gambling and hospitality.

Moreover, as the largest immigrant organization in the state of Nevada, the Culinary Union has been actively advocating for its members for over 80 years: “This country was built on the backs of slaves, on land stolen from Indigenous peoples, and most of its inhabitants are descendants of immigrants. We will not be silent as our government discriminates based on religion and national origin—it is unconstitutional and shameful. Refugees are welcome and we should let them in. When our communities are under attack, we will stand up and fight back to ensure that all people who make this country great have a seat at the table” [

36]. In this spirit, their posts, leaflets and newsletters are written both in English and Spanish.

This vision is operationalized in a number of different ways. For example, men and women in union positions are paid the same, while across the United States, women are paid USD 0.79 for every dollar a man earns. Yet another example is that members are protected against sexual harassment and gender discrimination, and when cases arise, there is a clear grievance procedure to be rehired and to recoup lost wages. In this manner, the union not only represents, according to Arguello-Kline, “57,000 people but [their] 174 countries [as well]. Yeah, there are people from all over the world in the properties we represent. Majority Latinos and majority women but we have people from Ethiopia, we have people from Bosnia, Serbo-Croatians, Asians … We make leaflets in a lot of different languages you know, for people they can get the information in their own language. That make us very, very strong ... you know, because we [work with] all the different ethnic groups” [

34].

The free immigration classes are in partnership with the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada and are taught both in English and Spanish. In collaboration with the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada and the National Partnership for New Americans, the Culinary Union held a series of citizenship fairs in preparation for the 2016 presidential and national elections. In fact, some of the Culinary Union’s members took a leave of absence to assist with the fairs and help people fill out applications in one-on-one appointments [

37]. At another such fair in 2018 that had 250 attendees, the Culinary Union featured “immigration experts offering free consulting services for members and their families who are eligible to obtain American citizenship, or those who are curious on the steps to qualify” [

38]. The union’s Citizenship Project is an example of how it helps shape the city by embracing the realities of politically-engaged urbanism [

39].

4.2.4. Public Realm: Housing

Housing can be considered to be an essential part of the public realm because it constitutes a basic need and is a fundamental link to the everyday chain of movement and experience in the city (e.g., going from living to working to shopping and other everyday activities). There is also an argument to be made for rights-based approaches to affordable housing, in which housing is seen as a basic human right. These can be quite critical, since the scope and complexity of the housing crisis demands a public—in the sense of a collective effort rather than a private profit-driven approach—response in order to have an effective large-scale impact. Rights-based approaches can also be effective in mobilizing and directing action [

40]. While they may not always guarantee particular outcomes, they can insist on efforts and resources being brought to bear on the problem. They can also create social agreements, especially if led by social and political movements like labor unions, that are needed to create a political consensus around the idea that access to affordable housing is a fundamental contributor to the public realm of the city.

In recent years, Las Vegas has faced multiple housing problems. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, Las Vegas became the epicenter of the housing bubble collapse in the United States. Thousands of homes were foreclosed, many having been built with the very wages that the Culinary Union had bargained for. In 2009–2010, Las Vegas had the nation’s highest foreclosure rate, with one out every nine housing units receiving a foreclosure filing [

41]. More recently, in 2017, the Southern Nevada Regional Housing Authority was subject to budget reductions following President Donald Trump’s administration’s announcement of a 13.2% cut to the Department of Housing and Urban Development [

42]. In a 2018 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Las Vegas was the city with the most severe shortage of rental homes affordable to extremely low-income households. Furthermore, 84% of extremely low-income renter households in Las Vegas were severely cost-burdened [

43].

In the face of such housing challenges and as part of their contract negotiations in 2007, the Culinary Union asked Las Vegas companies to contribute to a fund to help union members and their families buy homes. As a result, over 1,700 Culinary Union members and their families have now bought their first homes with the help from the Culinary and Bartenders Housing Fund, which has provided over USD 12.5 million in down payment assistance and closing costs [

36].

The terms and conditions of the Housing Fund are quite generous and supportive of first-time house buyers—for example [

32]:

The down-payment assistance loan is up to USD 20,000 and has a 0% interest rate.

Members do not have to pay back the loan unless they sell, rent, or refinance the property.

Members must live in the house they buy (i.e., no second homes or vacation homes).

Members are required to complete an orientation class in English or Spanish and an 8 h homebuyer education course at no cost.

4.3. Agency in the Power Dynamics of the City

The narrative about the role of labor, as represented formally by unions, also relates to a body of work that focuses on the spatial political economy of the city e.g., [

3], and more specifically, how agency is asserted within its power dynamics e.g., [

10]. For those who have immersed themselves deeply into the everyday practices of designing cities and into the complex nature of such urban practices, it is obvious that processes of urbanism are fundamentally political, most evidently in the power relations and dynamics that yield decisions about which sites to select, what resources to allocate, how to involve communities or not, and what outcomes are considered desirable. Even taking a conventional stance such as “urban design is not political” is itself a political stance that positions itself as purely creative, technical and aesthetic, as if it is separate from the fundamental political-economy of a society. One of the principal reasons for the Culinary Union’s effectiveness in Las Vegas is that unlike conventional and professionally defined urban design practices, it understands and engages with political realities of urbanism. I now describe a number of practices through which the Culinary Union engages with—and indeed influences—the power dynamics of Las Vegas: negotiating, striking, grassroots leadership, organizing and mobilizing, and direct political engagement.

4.3.1. Practice: Negotiations

The union’s history over the last two decades is one of periodic labor-management disputes mixed in with extended stretches of labor-capital co-operation and partnership via negotiations [

8]. We can get a better grasp of this practice by looking at a few recent examples. “We’ve been in negotiations with the companies, and they are not giving the workers what they deserve according to the economy right now,” Arguello-Kline said after the first voting session in 2018. “They are very successful. They have a lot of money” cited in [

44]. For the new 5-year contracts that year, the union sought annual raises of 4 percent and added protections for workers, including a panic button for housekeepers to alert authorities if they are under duress. [

45].

Additionally, in 2018, right before the previous contract expired, the Caesars Entertainment company, which owns several large casino-hotel-resorts, struck a tentative deal with the Culinary Union, covering about 12,000 workers at nine of its properties [

46]. The union asked for training of new skills and job opportunities as companies adopt technology that can displace employees. It also wanted contract language that would protect workers if properties were sold. The Culinary Union also proposed that an independent study be carried and be paid jointly with the companies and the union to analyze the workload of housekeepers. A few days later, a deal was struck with the MGM, covering 24,000 employees at 10 casino-hotel-resorts. After this, the union focused its efforts on negotiations with 15 other casino corporations not covered by the deals with Caesar and MGM [

46,

47].

There are consequences and benefits of negotiation as a practice. The union has the power to decide how employer contributions are distributed after each contract negotiation. For each year of its 5-year contracts with Las Vegas casinos, the union decides how much of an increase in employer contributions are allocated between wage increases and contributions to the union’s pension and health plans. For example, the opening of the in-house pharmacy in 2003 reduced healthcare costs, which thereby allowed for an increase in wages. As a result, union workers on the Las Vegas Strip saw wage increases of 60 cents per hour, which is a total of USD 1248 per year, while union workers in downtown Las Vegas saw wages jump by 25 cents per hour, or USD 1,248 for the year. The wage increases were estimated to have injected USD 50 million into the Las Vegas economy [

48].

For the Culinary Union, the end goal of the practice of negotiation is not just higher wages, but a broad-ranging collective agreement (i.e., a new contract) in the process, as described by Arguello-Kline: “Yeah, you know, through our contracts ... every 5 years or every 4, depending how long ... the contract (is), we’ve been improving our contract(s) in every negotiation (where) we see ... an opportunity. Like in 2007, we did the Housing Fund and (due to) that fund ... for the first time, people (could) have their first home. You know that was a big say in our contract and before that, we had the training fund (which)is a partnership between the company and the union. Through our contract, we have a fund (to) establish the Culinary Academy where the workers inside the hotel, they can have an opportunity to switch their job(s) (and) not (be) trapped in the job” [

34].

4.3.2. Practice: Strikes

The Culinary Union has a history of utilizing the practice of strikes strategically to obtain not only immediate short-term benefits but also long-term political influence. I now describe a few key moments and turning points in the use of this practice.

In 1984, the Culinary Union launched one of the largest strikes in Las Vegas history, deploying more than 17,000 workers to protest 32 Las Vegas Strip casino-hotel-resorts. Members picketed for 9 months until 900 of them landed in jail and six casinos severed their ties with the union [

49]. Five years later, in 1989, labor unions struck the Horseshoe Casino after its owner, Jack Binion, who recently had inherited the property from his father, refused to accept the same provisions of the labor agreements that Las Vegas Strip properties had signed. Striking workers maintained picket lines outside the property for 9 months, until Binion finally agreed to a 4-year contract that hiked wages and benefits in return for work-rule changes that enhanced his control over hiring and firing [

50]. The success of the Horseshoe strike was particularly notable because it revived strikes as a viable practice [

51].

On 21 September, 1991, the longest successful strike in Las Vegas and United States history began when 550 employees, including housekeepers, servers, cooks and hotel bellmen of the Frontier Hotel walked out of their jobs [

20,

52]. The strike was led by the Culinary Union, and was joined by the Bartenders Union Local 165, Teamsters Union Local 995, Operating Engineers Union Local 501, and Carpenters Union Local 1780. The provocation for the strike was that the Frontier Hotel refused to sign the labor contract that had passed with the approval of most other casinos, because the hotel said it could not—or would not—provide the same benefits as the other casinos and hotels. The 550 workers maintained a picket line in front of the hotel 7 days a week and 24 hours a day. In 1998, the hotel was sold to wealthy businessperson Phil Ruffin, and on February 1 of that year, the strike ended after nearly 6 ½ years.

The longevity of the Frontier Hotel strike was evidence of the union’s strength and persistence. Moreover, most of the businesspersons and heads of the corporations that that now owned many of the major developments did not like the spatial implications of a strike, because it represented a supposed eyesore of picketing workers in front of their expensively remodeled and now more “family-friendly” Las Vegas Strip. Strikes, or threats of a strike, as a mode of urban practice, continue to be deployed on an ongoing basis by the union. For example, in March 2014, union members voted to authorize a call for strike if contract negotiations with 17 casinos were not successful [

53]. In May 2018, union members voted to authorize a strike on 34 casino-hotel-resorts in Las Vegas if contract negotiations were unsuccessful after their current contracts ended [

54,

55].

4.3.3. Practice: Grassroots Leadership

Las Vegas is a magnet for immigrants, whether the city is their original destination or they arrive via another port of entry, most commonly the nearby city of Los Angeles. The economic boom from the 1990s through the 2000s created tens of thousands of service and construction jobs that were filled by persons without specialized skills or native knowledge of English. While beginning salaries rarely exceeded the minimum wage, persistence and the acquisition of skills led to substantial improvements in salary, although infrequently in benefits. The most prized jobs have been in the casino-hotel-resorts, particularly those that have contracts with the Culinary Union [

56].

Primarily as a result of such immigration, the population of Las Vegas continues to diversify. In 1980, the city’s population was approximately 82.5% white, 9.8% black, and 7.4% Hispanic, with a few thousand Asians and Native Americans making up the rest. Nearly 40 years later, in 2018, the city was 62.1% white, 31.4% Hispanic, 11.3% non-Hispanic black, 9.6% Asian, and 0.5% American Indian [

57]. While this diversity reflects larger demographic trends, the Culinary Union is particularly active with and supportive of immigrants and women. Among such members are those who belong to some of the largest job categories in the city [

18], with the second largest being in food preparation (with a total of 30,950 workers in the city), the third largest being servers such as waiters and waitresses (29,310 workers), the fifth largest being general cleaners such as janitors (22,970 workers), and the seventh largest being housekeepers such as maids and hotel room attendants (21,980 workers).

It has been estimated that over 80% of housekeepers in Las Vegas hotels are immigrants or women of color [

8], and the union representatives reflect this demographic. Studies have revealed the important role played by women in organizing the hotels and casinos in La Vegas, with a specific focus on their development of a culture of resistance [

58]. Workers are no longer fighting for simply the extrinsic rewards of good pay, and instead are focused on the intrinsic rewards of high self-esteem in the work they do. This is particularly relevant to creating a culture where work and its ostensible rewards are valued while also valuing mental and physical health, social bonds, and justice (which are all crucial aspects of a more humane urbanism).

The Culinary Union has long prided itself on its comprehensive organizing tactics, including active involvement of members such as housekeepers, servers, cooks, laundry workers, and so forth to rise into leadership positions [

8]. For example, in 1990, Hattie Canty became the first African American woman to be elected to be president of the Culinary Union. Canty, a strong leader and former hotel housekeeper from the Maxim Hotel and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip, was instrumental in creating the Culinary Academy. That an African American woman would lead the city’s largest union during the 1990s resort boom and the legendary Frontier Strike served as a sharp contrast to the largely white and male demographics of corporate management [

59].

Far beyond the tropes of “community participation” or “community engagement” that commonly populate conventional practices in urbanism, the Culinary Union’s practice is about cultivating radical new power dynamics and structures that enable new types of revolutionary leadership. In that spirit, in 2012 Geoconda Arguello-Kline, a Nicaraguan immigrant and a former housekeeper at the Fitzgerald’s Casino in downtown Las Vegas, was elected as the first Latina leader—with the title of Secretary-Treasurer—of the union. Arguello-Kline also serves as Vice President of UNITE HERE and is a board member of the Culinary Academy, the Citizenship Project, and the Culinary and Bartenders’ Pension Fund (see

Figure 4). In addition, there is a direct link between local grassroots leadership of the Culinary Union in Las Vegas and its national leadership in Washington DC, such as when D. Taylor, former Secretary-Treasurer of the Culinary Union, became the President of the parent union UNITE HERE in 2012.

4.3.4. Practice: Organizing and Mobilizing

In order to grow larger and increase its influence, the Culinary Union regularly deploys the practice of organizing and mobilizing current and future members, according to Arguello-Kline: “I think that one of the future(s) of the union is always to grow. Growing for us is have more families with better standard of living and making stronger the union. That’s one of the big future(s) we (are) looking for all the time, that’s why we (don’t) stop ... organiz(ing)” [

34]. Another major reason why union workers organize is to enable large-scale efficiencies of the elaborate welfare and education services provided by the Culinary Union, including health insurance, pension schemes, and providing critical advice for home ownership, as described in a previous section. In the same vein, the union offers courses in the professions that are a part of the hotels and casinos, and employers co-fund these courses as they provide valuable competence. As such, Culinary Union and casino-hotel-resort companies collaborate to remain competitive and build reputations of providing high-quality services. English as a second language is an integral part of these courses since a large proportion of workers are immigrants.

However, organizing and mobilizing can be extremely challenging and are not always successful. For example, the efforts to organize Station Casinos went on for many years and every effort has received a strong pushback from the company and from local newspapers such as the conservative

Las Vegas Review-Journal. In 2012, the company released an advertising campaign that depicted the union as an organization that does not care about its members but only wants more money to make its leaders richer each year. This was in response to union members who supposedly wanted “to scare away business from Station Casinos properties by picketing the company’s vendors, asking entertainers not to perform at the company’s venues and challenging the business practices of Deutsche Bank AG, which owned 25 percent of the casino operator” [

60]. To this day, the Station Casinos company and the Culinary Union are at loggerheads over organizing efforts, with a mixed record of successfully organizing workers at some of their properties while at others, workers voted not to join the union.

4.3.5. Practice: Direct Political Engagement

The practice of direct political engagement stems from an uneven distribution of power in the city. In Las Vegas, no other group has as much political influence as the owners of casinos, hotels and resorts taken together as a group, so much so that that the general perception used to be that no one has a chance of winning or holding onto elected office without the support of the gambling and hospitality industries [

61]. However, in 1996, the Culinary Union mounted a successful campaign to defeat an incumbent state senator who was also an anti-union hotel owner and in 1998, the union’s efforts were influential in a number of races, such as when the union’s door-to-door campaigning helped to defeat candidates supported by Sheldon Adelson, owner of the then new and non-union Venetian Casino-Hotel-Resort [

52].

The Culinary Union had the largest political operation in the state of Nevada, when during the 2016 national elections, 300 UNITE HERE and Culinary Union members took a 2-month leave-of-absence from their hotel and casino jobs and knocked on over 350,000 doors, talked to over 75,000 voters, and delivered 54,000 early votes as political organizers. The union went into election day with over 60% of membership registered to vote and with its members fully engaged. With the union’s substantial assistance, Nevadans elected the first Latino to U.S. Congress (i.e., Ruben Kihuen), the first Latina to the U.S. Senate (i.e., Catherine Cortez Masto), and former Culinary Union political director, Yvanna Cancela, was appointed the first Latina state senator in Nevada.

4.4. Culinary Union as Case Study

Before I go on to discuss the findings of this research in the concluding section, I should clarify that the purpose of this research has not been to put the Culinary Union on a pedestal and to proclaim it as some sort of best practice; rather, the goal is to critically analyze the practices of the union and to examine the implications of such an analysis of their contributions to the urbanism of Las Vegas. Thus, the union has indeed had a history of problems and challenges. For example, in 1977, the U.S. Labor Department stripped control of the pension fund from a Culinary Union trustee for allegedly making improper and unsafe loans totaling about USD 30 million [

62]. In 1998, a court-appointed monitor found widespread financial wrongdoing in the Culinary Union’s parent union, HERE (a group that had been linked previously to organized crime), accusing its former president in particular for using union money for personal activities, such as flying his wife to the resort town of Palm Springs in California [

63]. In addition, the Culinary Union has the long-term goal of building membership from stable properties while avoiding short-term risks, which has led to its appearance at times as an uncaring organization. For example, in 1998, the union decided not to organize workers from the Boardwalk Casino after businessman Steve Wynn bought it, since there were rumors of it being demolished [

64]. Similarly in 2008, it avoided organizing housekeepers at the Imperial Palace Casino and Hotel despite them delivering a petition with 100 signatures. “It’s sad when you have people who want their help, willing to pay union dues, and the union doesn’t want to hear anything,” said one housekeeper, who spoke anonymously because of fear of management reprisal cited in [

64]. The union replied at the time that it had a long-standing policy to avoid organizing workers at casinos with uncertain fates.

5. Conclusions: Insights and Implications for Urban Practice

What the empirical evidence demonstrates is that the effectiveness of the Culinary Union in the urbanism of Las Vegas is due to a number of outward-facing reasons. It is part of an active and powerful national union UNITE HERE, it leverages policies of the U.S. federal government such as when it calls attention to enforcement of its labor laws, it harnesses the influence of the local government in Las Vegas on specific issues either by challenging it publicly or by collaborating with it on common concerns, it works with against or with the dominant players in the local casino and hospitality industries, it partners with other nonprofit organizations on public realm issues such as health and economic opportunities, and it focuses on economic justice issues such as fair wages and benefits combined with larger societal concerns usually embraced by social and political movements (e.g., citizenship rights and political representation). There are also inward-facing reasons for the union’s effectiveness, such as its commitment to allocating roughly 40% of its annual income to external organizing, building a significant union density so as to increase upward pressure on the wages of non-unionized casinos and hotels, and instituting a wide net of social benefits for its members and their families.

The local government of the City of Las Vegas recognizes this effectiveness and tries to work with the union on a project-specific basis, especially for the engagement of non-traditional actors in planning processes. For example, the head of Las Vegas’s planning department stated that “one of the strategies that we’ve been discussing in kind of the non-traditional sense for outreach, is going and using things like (the) Culinary (Union) because they have such a wide breadth of people in our community and trying to figure out if there’s a partnership opportunity with Culinary or some of the other trade unions. (For example,) one of the things that we found, specifically with Culinary in some of the research that we do, they have a lot of access amongst our under-served and minority populations. And a lot of the traditional things that we do in planning to do outreach doesn’t usually serve those populations” [

65].

What is significant is that taken together, the organizing, mobilizing, services and political efforts of the Culinary Union create an ambience of care and protection to confront the traditional precarity engendered by the traditionally top-down gambling, hospitality and related service industry jobs that are often characterized as low-skilled and dead-end with a low quality of life (e.g. see

Figure 5). Diana Vallez describes this approach from a worker’s perspective: “The majority of our staff here is rank-and-file; we all came from the hotels. And I think key to doing what we do to organize people is, you need to feel the pain of the worker. When they’re suffering, it has to hurt you. Not (only) hurt you but give you the courage to do something about it. And why? Because I’ve been there. I know what it is to clean a toilet. I know what it is to cook. I know what it is to have a cook breathing down your neck. And the day that you don’t feel that, probably it’s not the time for you to be here” cited in [

41] (pp. 9–10).

This case study analysis points to three major implications for urban practice in terms of a more democratic and equitable spatial production of cities. First, this article shows that while labor unions may not directly shape the city in the ways that conventional expert-driven top-down design processes are supposed to, they can substantially help to alter its spatial political economy at the local level. Second, in the absence of a powerful public planning presence in the neoliberal context of contemporary cities such as Las Vegas, labor unions are among the few influential organizations countering urban precarity through direct actions. Third, the success of labor unions in places such as Las Vegas is also due to particular spatial features of the city, such as the densities of activity that facilitate effective protests, organizing and ongoing training. Union activism can be seen as one form of transformative practice in urbanism [

7] (pp. 16–17): “We know from labor history that unions are formed not only in the workplace but also from working-class communities in which social networks and forms of solidarity create a capacity and a willingness to engage in risky collective action. Organizing requires time and energy that are not spent commuting to far-flung employment or in domestic labor, and social unionism requires that workers and community allies share local space in which to assemble, that they continue to demand the right to shape that space, and that they have an effective political right to do so.”

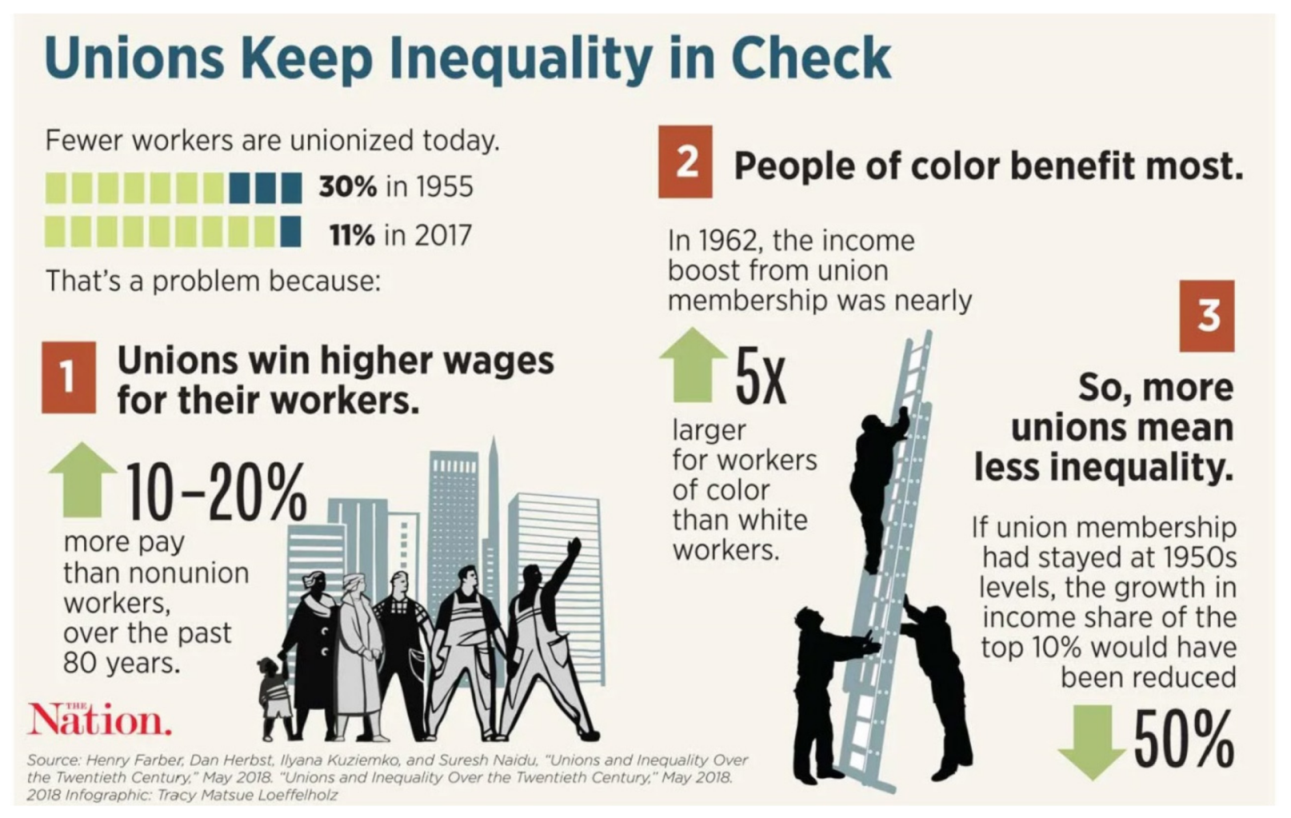

Beyond the specific case study of the Culinary Union in the local context of Las Vegas, unions have played a significant role in reducing structural inequalities at the national scale (e.g., see

Figure 6). Of course, not all unions are as democratic and progressive as the Culinary Union, and there is indeed a long history of unions that are patriarchal, racist or corrupt. As this case study analysis reveals, the particular type of union and the particular natures of its urban practices matters. Still, based on survey data of union households dating all the way back to the 1930s, Farber and his colleagues [

66] found multiple benefits of unions. For example, African-Americans in the United States secured a significantly higher wage premium by joining unions than whites. This should not be surprising, given that unions shield individual workers from exploitation and without collective protections, African-American workers in mid-century United States were especially vulnerable to abuse by their employers. It is a useful reminder that strengthening labor unions is a necessary plank of any serious agenda for racial justice in the U.S. Ultimately, unions that include the pursuit of narrow economic interests such an increase in wages, but then also stretch their mandates far beyond that into social justice issues such as job security and building grassroots leadership and ally with civil organizations that seek broader community benefits such as vocational training and access to housing tend to be the ones that contribute the most to urban transformation. In other words, social movements—such as labor unions—act as urbanists when they actively represent and the under-represented in the spatial political economy of the city and thereby assert their agency in processes of urbanism.