The Beautiful Risk of Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Research. A Challenging Collaborative and Critical Approach toward Sustainable Learning Processes in Academic Profession

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background to Interdisciplinary Learning Ethos

1.2. Theoretical Approaches and Current State of the Research Field

1.2.1. Research Approach: Risk and Holistic Pluralism

1.2.2. Toward Interdisciplinary Research Practices

Interdisciplinary research is any study or group of studies undertaken by scholars from two or more distinct scientific disciplines. The research is based upon a conceptual model that links or integrates theoretical frameworks from those disciplines, uses study design and methodology that is not limited to any one field, and requires the use of perspectives and skills of the involved disciplines throughout multiple phases of the research process [30].

1.3. The Purpose of the Study

- What does interdisciplinary knowledge creation entail in our research context?

- How could possibilities and challenges of interdisciplinary research be approached based on our research process?

- Why is this important?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology: Our Methodological Standpoints Autoethnography and Mixed Methods

To me, our project-group is a research finding in itself (Melin, MCS and Journalism).

2.2. Research Design and Methods

2.3. Empirical Research Materials

- Our embodied academic background and pedagogic experiences, which we brought with us into stages one and two of our research process.

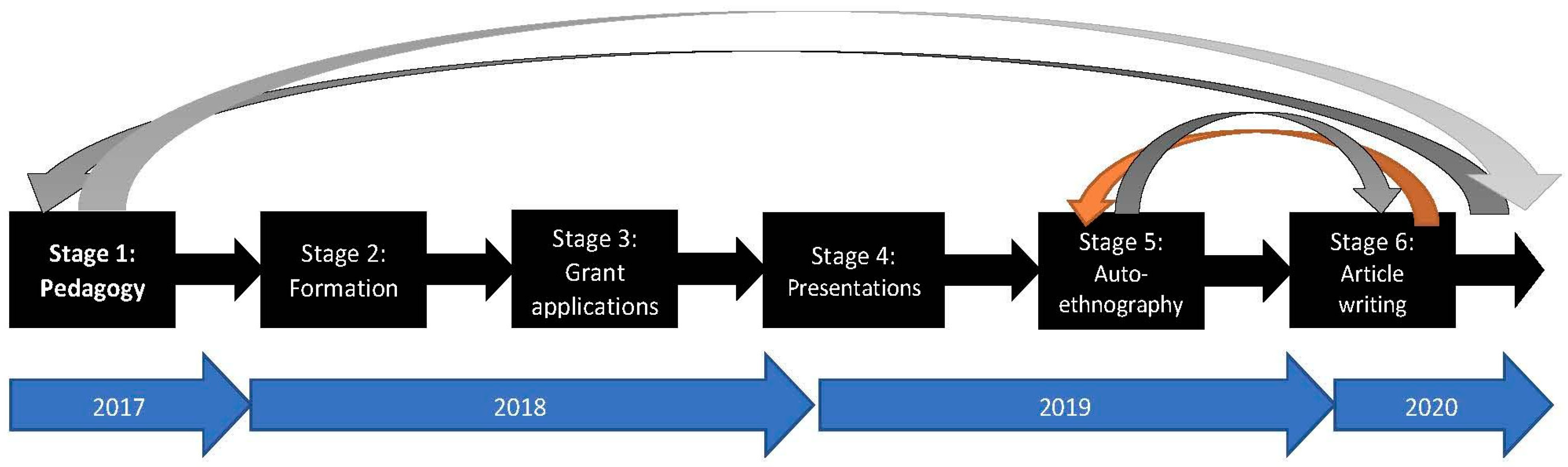

- Four research grant applications and, in addition, each application received reviews from external grant fund referees. This was collected during stage three of our research process (Figure 1).

- Autoethnographic reflections about our experiences of our collaborative research and writing process, which consisted of reflective diary notes from the four researchers. This was the outcome of stage five of our research process.

- Ethnographic review: An ethnographic researcher—Dr. Erin Cory—read and analyzed our applications and autoethnographic reflections in order to achieve an outside view on our process. This review has guided our continued autoethnographic research. This was the outcome of stage five of our research process.

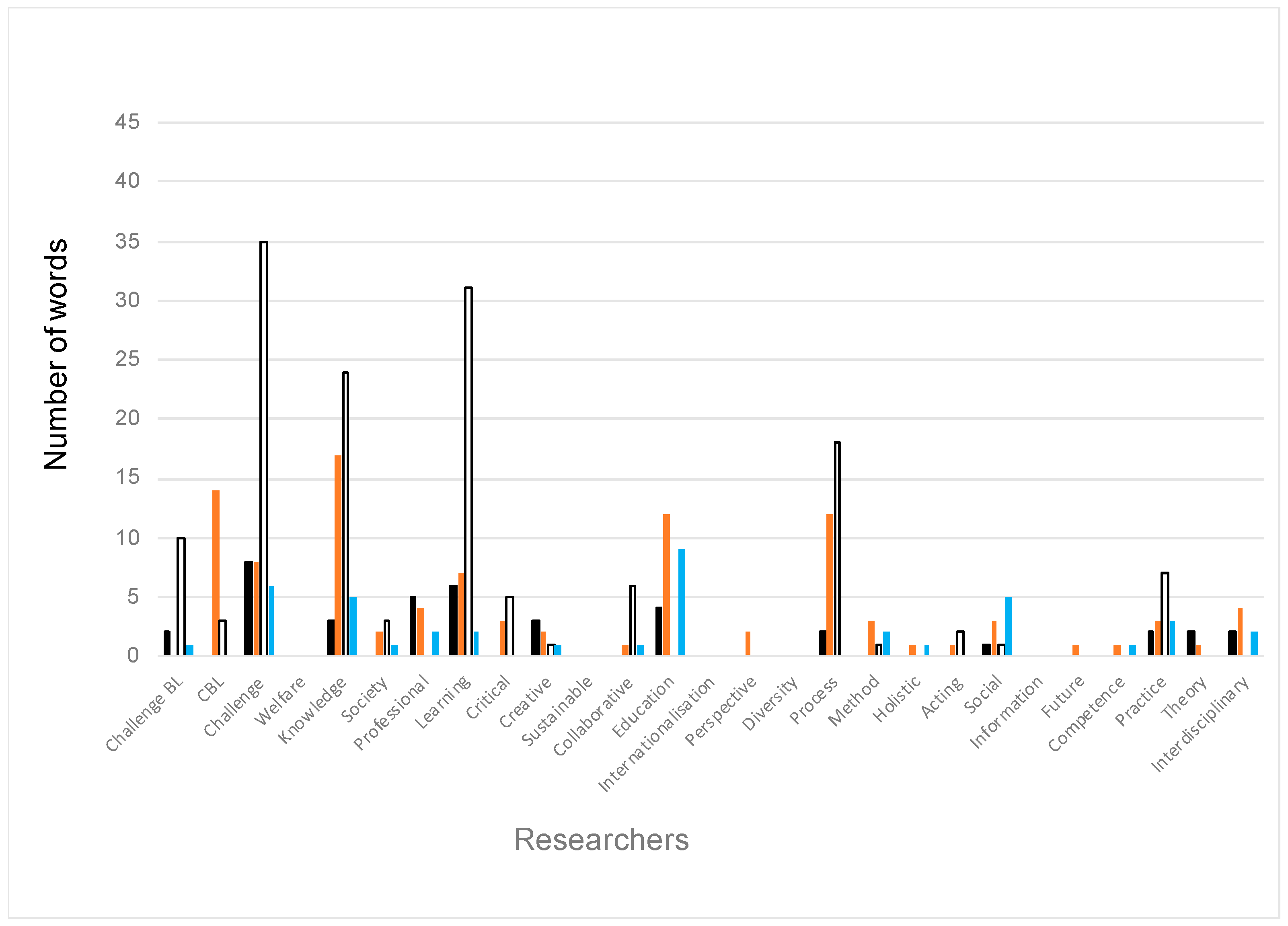

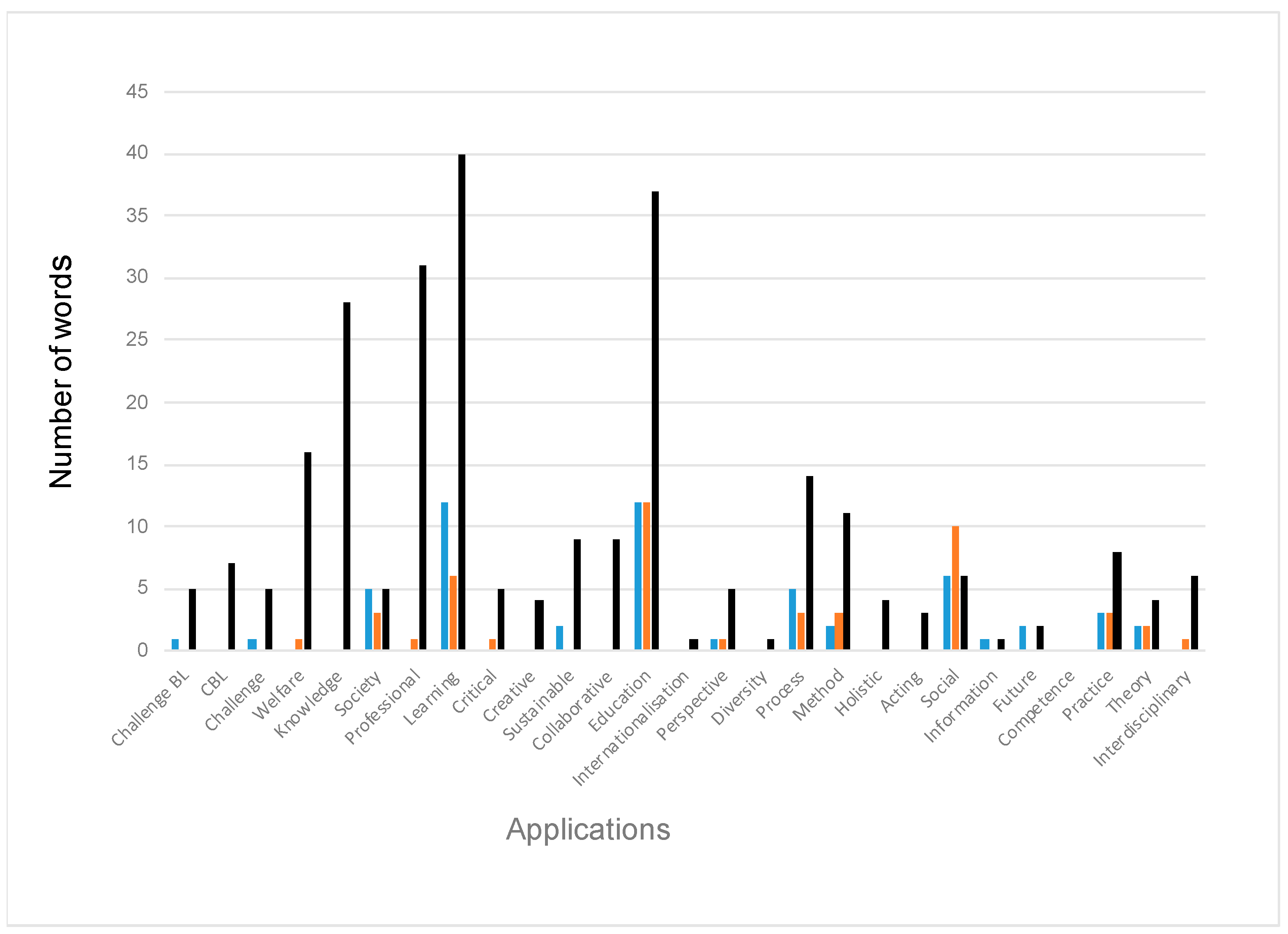

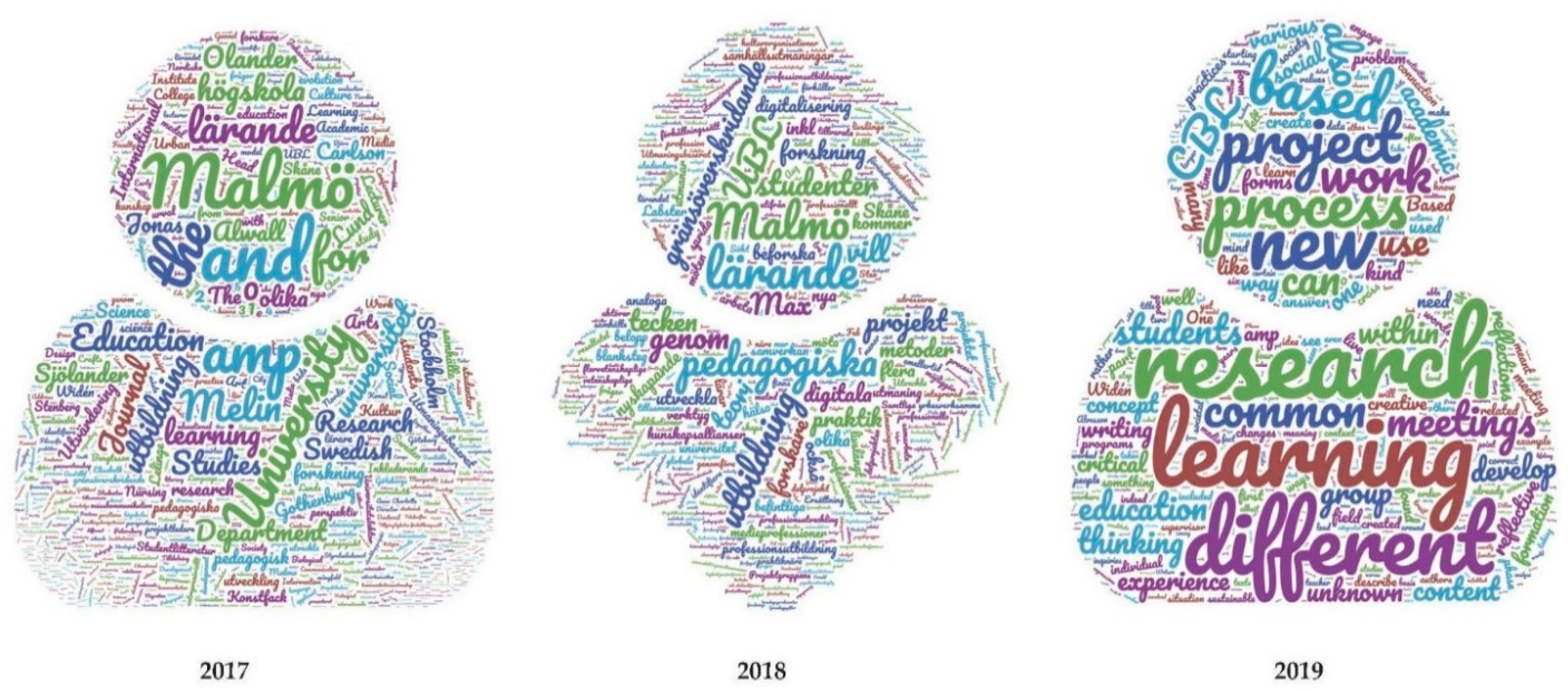

- Statistics and word clouds of the word count in both our research applications and our autoethnographic reflections in order to see what words we have used and to engage a self-critical analytical and deconstructive mode. This was the outcome of stage five of our research process (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

- Four researchers’ individually written shorter reflections on the word count we did as the basis for the analysis in our article writing process. Thus, this was the outcome of stages five and six of our research process (Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. The Challenge of Working in Collaboration

All my professional life, I have worked interdisciplinary and did indeed embrace the challenge this new situation provided. However, getting the 50 [researchers] to create creative and lasting project-groups with the task of writing research applications turned out to be difficult. Interesting round-table discussion was followed by even more interesting round-table discussions, but I felt that nothing happened. In challenging interdisciplinarity I felt I was stuck in limbo. Eventually, and actually mostly by chance, I sat down next to a colleague of mine and his table, and after ten minutes I realised this was a project group consisting of six researchers from four faculties, covering six vastly different subjects. This included my own as I became aware that I had joined the group by sitting down with them. And this was exciting and rather scary (Melin, MCS and Journalism).

A lack of knowledge of other researcher’s disciplinary knowledge tend /…/ to hinder or at least not nourish academic collaboration. And in contrast an interdisciplinary bridge building in this collaborative project setting has enabled closer professional relations in terms of a mutual understanding and appreciation (both depth and breadth) of old as well as new research fields through the CBL-project (Widén, History of Education and Humanities).

I remember that concrete examples out of societal challenges encouraged colleagues to address these challenges in some new directions only by the fact that the colleagues, in practice, met others with different subject disciplines and backgrounds, strengthened my perception of how synergies in knowledge formation can be achieved through cross-border meetings (Christensen, Social Science Education).

The idea of working interdisciplinary between different research disciplines /other researchers has been a strong driving force for me during my academic work. Creating a joint educational project that covers different subject areas would be exciting and interesting. From being focused within a fairly narrow research area of biology, I have wanted to make new challenges and find other approaches within my projects (Ekelund, biology and natural science).

3.2. The Challenge of Taking Time

Is it possible for me, through this project together with colleagues from other disciplines, to develop my own educational thinking? What do we have in common and what differences do we have to face from our different disciplines? (Ekelund, biology and natural science)

In my experience the result of learning new content knowledge is many times dependent on trusting in something that is known to us, either known content knowledge or the use of known work models. And that takes time. Either way, we engage with new knowledge and we support our learning by simultaneously relying on some aspect that is already known to us (Widén, History of Education and Humanities).

3.3. The Challenge of Knowing the Not-Known

If you go outside your own comfort-zone, you’ll face a risk, however, it also forces you to reflect in new ways (Christensen, Social Science Education).

Four different disciplines, four different linguistic jargons, four different academic practices, but one project group. A group of scholars who have worked through the hardship of writing and having application proposals rejected, as well as receiving research funds. We have got to know each other and our different ways of thinking and doing. During the series of meetings, which indeed have been conflictual, albeit on a very academic low-key level, we have managed to help each other over various gaps, and found bridges over our disciplinary borders to cross (Melin, MCS and Journalism).

The challenges and risks are great when developing cross-cutting projects. Do we understand each other within the group where the subject background shows a high degree of variation? Does it benefit us in our academic merit and if not why then? Do we have patience in a job like this that takes time and may not be appreciated by other colleagues? Daring to take these risks has probably strengthened our commitment with the goal of creating something in common (Ekelund, biology and natural science).

When it comes to growing and developing our professional knowledge, we are really up for a learning challenge. As academic researchers we are rightfully held by the public, the academic community and by ourselves to be knowledge experts in various respects. In that sense, acquiring a Challenge Based Learning-approach does not come easy. We, who are believed to know things, why should we voluntarily be involved with risks and challenges of practicing and handling things we do not yet know. But in order to learn new things it is imperative that we continuously engage in and develop the approach and mindset of taking risks and put ourselves up to learning (Widén, History of Education and Humanities).

3.4. The Challenge of Creating a Learning Environment

It is through encounters between people of diverse backgrounds, cultures and frameworks that we are challenged in our notions, not least in learning environments and contexts (Christensen, Social Science Education).

The possibility to meet and learn from colleagues from other academic disciplines, encouraged me the most in those first meetings, being a part of a new learning environment. This really helped me to develop my own critical thinking in and about the academic profession. It made things very concrete and raised my awareness of the importance of cross-border meetings. The discussion enabled me to face and handle the question and discussion of various definitions, bringing new insights to the meaning of interdisciplinarity and collegial learning processes (Christensen, Social Science Education).

3.5. The Challenge of Forming Common Conceptual Knowledge

The project-group (which I will henceforth call it), started up meetings: discussion meetings, theory meetings, writing meetings and more writing meetings. These were nice, fun and interesting and I felt at ease in the group, albeit not at home, or even comfortable. I started to notice that I did not understand what my fellow colleagues said. It was like the tower of Babylon. Six different subjects meant six different jargons and professional languages, which meant that there were words used I had never heard before. We also used the same words, but the meaning was obviously very different. What is knowledge? What is research? What is “societal challenges”? What does “sustainable” really mean? One important piece of knowledge I have gained through this process is that over time, through meetings, by writing together and rewriting and rewriting even more, we have developed common understandings and a common knowledge base. And it is from that base that I write (Melin, MCS and Journalism).

The concept of knowledge varies greatly depending on the context in which you are. Scientific knowledge and, above all, natural sciences are, for me, strongly linked to data and facts based on experimental and empirical experience. In many cases, we refer to it as subject knowledge in relation to educational/didactic knowledge, which the debate often revolves around when educating teachers. These discussions have given me the concept of knowledge and a new broader dimension. Trying to understand new reflections and concepts probably increases my own knowledge (Ekelund, Biology).

Regardless, taken to the core, these professions [nursing, teaching, counseling, media work] are driven by rather similar educational ideals. And still, there is no real agreement amongst us what a professional group nor what professional knowledge is, possibly because the field of Profession Studies is not in agreement about this either (Melin, Media and Communication Studies and Journalism).

After that moment, creativity will never carry the same meaning to me. And at the same time, we use the word creativity differently, or not at all. For some of us, the term is revered, and for others it is seen as a threat to proper academic practice. Dwelling, confronting, provoking, discussing, writing together has, however, given an understanding of each other’s meanings and practice (Melin, Media and Communication Studies and Journalism).

However, of the somewhat narrow field of natural sciences, my view of knowledge has been developed through this interdisciplinary project. Discussing, analyzing and writing together in an interdisciplinary team (Ekelund, Biology).

4. Discussion

4.1. Create a Sense of Belonging by Retaining Previous Professional Experience

4.2. Cultivating a Sense of Curiosity and Inquisitiveness

4.3. Enabling a Collective Ethos of Handling Challenges

4.4. Fostering an Ethos of Risk Taking

4.5. Learning to Balance Thinking and Acting Critically and Creatively

If you knew when you began a book what you would say at the end, do you think that you would have the courage to write it? What is true for writing and for a love relationship is true also for life. The game is worthwhile insofar as we don’t know what will be the end [61].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Biesta, G. The Beautiful Risk of Education; Paradigm Publishers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pryke, M.; Rose, G.; Whatmore, S. Using Social Theory; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, S.M.; Rigano, D.L. Writing together metaphorically and bodily side-by-side: An inquiry into collaborative academic writing. Reflective Pract. 2007, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Vanasupa, L.; McCormick, K.E.; Stefanco, C.J.; Herter, R.J.; McDonald, M. Challenges in Transdisciplinary, Integrated Projects: Reflections on the Case of Faculty Members’ Failure to Collaborate. Innov. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorén, H. The Hammer and the Nail: Interdisciplinarity and Problem Solving in Sustainability Science. Ph.D. Dissertation, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, L. Educating for Good Questioning: A Tool for Intellectual Virtues Education. Acta Anal. 2018, 33, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D. Improving Teaching and Learning Together a Literature Review of Professional Learning Communities. Research Report; Karlstad University: Karlstad, Sweden, 2019; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón-Gallardo, S. Liberating Learning: Educational Change as Social Movement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S.E.; Savage, T. Challenge Based Learning in Higher Education: An Exploratory Literature Review. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christersson, C.; Christensen, J.; Ekelund, N.; Lundegren, N.; Melin, M.; Staaf, P. Challenger Based Learning in Higher Education-A Malmö University Position Paper. 2021; in progress. [Google Scholar]

- Dychawy Rosner, I.; Högström, M. A Proposal for inquiry of network and challenge-based learning in social work education. Tiltai 2018, 80, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwgren, J.; Reimer, B. Collaborative Media: Production, Consumption, and Design Interventions; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, E.; Wamsler, C.; Adolfsson, M.; Axelsson, M.; Beery, T.; Björn, H.; Bramryd, T.; Ekelund, N.; Jephson, T.; Narvelo, W.; et al. On the road to ‘research municipalities’: Analysing trans disciplinarian in municipal ecosystem services and adaptation planning. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, M. The Audit Society. Rituals of Verification; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wickström, J. Dekonstruerad länkning: En kritisk läsning av Constructive Alignment inom svensk högskolepedagogik och pedagogisk utveckling. Utbildning och Demokrati. 2015, 24. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-282612 (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Bornemark, J. Det Omätbaras Renässans: En Uppgörelse Med Pedanternas Världsherravälde; Volante: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, A.; Parcerisa, L.; Fontdevila, C. The growth and spread of large-scale assessments and test-based accountabilities: A political sociology of global education reforms. Educ. Rev. 2019, 71, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berasategi, N.; Aróstegui, I.; Jaureguizar, J.; Aizpurua, A.; Guerra, N.; Arribillaga-Iriarte, A. Interdisciplinary Learning at University: Assessment of an Interdisciplinary Experience Based on the Case Study Methodology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlbeck, P.; Widén, P. En skola som Utmanar. Om att Göra Skola Meningsfull ur Elevers Perspektiv; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Kulturens väv; Daidalos: Uddevalla, Sweden, 1996/2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, J.T. Questioning and Teaching. A Manual of Practice; Resource Publications: Eugene, OR, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbernner, U. The Social Ecology of Human Development: A Retroperspective Conclusion. In Brofenbrenner, Urie. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development, The SAGE Program on Applied Developmental Science; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Danaher, P.A.; Davies, A.; De George-Walker, L.; Jones, J.K.; Matthews, K.J.; Midgley, W.; Arden, C.H.; Baguley, M. Resilience and Capacity-Building. In Contemporary Capacity-Building in Educational Contexts; Palgrave Pivot: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, B.J.; Miller, F.; Barnett, J.; Glaister, A.; Ellemor, H. How do we know about resilience? An analysis of empirical research on resilience, and implications for interdisciplinary praxis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014041. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.C. Interdisciplinarity: Its Meaning and Consequences. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelela, S.W.; Larson, E.; Bakken, S.; Carrasquillo, O.; Formicola, A.; Glied, S.A.; Haas, J.; Gebbie, K.M. Defining Interdisciplinary Research: Conclusions from a Critical Review of the Literature. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Max-Neef, M.A. Foundations of transdisciplinarity. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E.; Mcdermott, R.; Snyder, W.M. Cultivating Communities of Practice; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.; Thönnessen, J.; Weber, B. Knowledge creation in reflective teaching and shared values in social education: A design for an international classroom. Educ. 21 J. 2020, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjeregaard, L.; Mačiulskytė, S.; Aciene, E.; Christensen, J. Towards a Model of Social Innovation: Cross-Border Learning processes in Dementia Care in the Context of Ageing Society. Soc. Welf. Interdiscip. Approach 2018, 1, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.M. Diversity Overcoming Obstacles to interdisciplinary research. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Wiek, A.; Bergman, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C. Trans disciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Ness, B.; Schweizer-Ries, P.; Brand, F.S.; Farioli, F. From Complex Systems Analysis to Transformational Change: A Comparative Appraisal of Sustainability Science Projects. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R. Managing earth’s ecosystem: An Interdisciplinary challenge. Ecosystems 1999, 2, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M. Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 1999, 402, C81–C84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P. Autoethnography as a method for reflexive research and practice in vocational psychology. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2008, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.W.; Young, A.W. Human Cognitive Neuropsychology: A Textbook With Readings; Psychology Press: Hove, East Sussex, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau, P. Participant Objectivation. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2003, 9, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Holman Jones, S.; Ellis, C. Autoethnography: Chapter 1; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, D.; Durán-Rodas, D.; Ferri, A.; Kuttler, T.; Magelund, J.; Mögele, M.; Nitschke, L.; Servou, E.; Silva, C. What is Interdisciplinarity in Practice? Critical Reflections on Doing Mobility Research in an Intended Interdisciplinary Doctoral Research Group. Sustainability 2020, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.; Sterling, S.; Goodson, I. Transformative Learning for a Sustainable Future: An Exploration of Pedagogies for Change at an Alternative College. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5347–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, A. Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues Educ. Res. 2006, 16, 52–56. Available online: http://www.iier.org.au/iier16/moghaddam.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Tuckman, B. Developmental Sequence in Small Group. Group Facil. A Res. Appl. J. 2001, 63, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R. Population, Sustainability, and Earth’s Carrying Capacity BioScience; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; Volume 42, pp. 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, K. A look at how the ecological systems theory may be inadequate. In A Capstone Project 2007; Winona State University: Winona, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Skoldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-8039-7707-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chism, N.V.N.; Bickford, D.J. (Eds.) The Importance of Physical Space in Creating Supportive Learning Environments: New Directions for Teaching and Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla, V.B.; Duraisingh, E.D.; Wolfe, C.R.; Haynes, C. Targeted Assessment Rubric: An Empirically Grounded Rubric for Interdisciplinary Writing. J. High. Educ. 2009, 80, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.; Bergmann, M.; Keil, F. Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Widén, P. Att mäta och att mätas-bedömning, inspektioner och skolledarskap. In Upplyftande Ledarskap i Skola och Förskola; Riddersporre, B., Erlandsson, M., Eds.; Natur & Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aspelin, J. Lärares Relationskompetens: Vad är Det?: Hur kan den Utvecklas? Liber förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. Tusen Platåer: Kapitalism och Schizofreni; Tankekraft Förlag: Hägersten, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kupferberg, F. Farvel til “de rigtige svars” pædagogik. In Kreativitetsfremmende Læringsmiljøer i Skolen; Tanggaard, L., Brinkmann, S., Eds.; Dafolo: Fredrikshamn, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. “Truth, Power, Self.” Interview. In Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Researcher | Christensen | Ekelund | Melin | Widén |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender/age | Male/58 | Male/64 | Female/57 | Male/51 |

| Position | Senior Lecturer/Associate Professor | Professor | Senior Lecturer/Associate Professor | Senior Lecturer/Associate Professor |

| Subject for PhD | Education, 2010 (Lund Uni, Sweden) | Plant Physiology, 1988 (Lund Uni, Sweden) | Media and Culture Studies, 1996, (Queen Margaret University, Scotland) Journalism, 2008 (Gothenburg Uni, Sweden) | Educational History, 2010 (Linköping Uni, Sweden) |

| Subject of employment | Social Work, especially organization | Biology | Media and Communication Studies | Pedagogic Practices |

| Department | Dept of Social Work | Dept of Natural Sciences, Mathematics, Society | School of Arts and Communication | Dept of Culture, Languages, Media |

| Teaching experiences | Social policy Social innovation Welfare studies Educational Sciences Research methods and theory Supervision at BA and MA level | Biology courses Scientific methods Educational Sciences Supervision at BA, MA and PhD level | Cultural industry & journalism Media History Visual culture Communication Research methods and theory Supervision at BA, MA and PhD level | Educational Sciences Research methods and theory Supervision at BA and MA level |

| Common experiences | Teaching teachers-in-training at the Faculty of Education and Society Coordinating, teaching and supervising on internship courses Teaching at different faculty courses Teaching at graduate, postgraduate and PhD levels Researching Teaching and Learning in Higher Education | |||

| Activities 2017–2020 | Year |

|---|---|

| Start-up Workshop (80 researchers, 5 faculties) | 2017 |

| A series of workshops around Societal Challenges and Learning—group allocations (50 researchers, 5 faculties) | 2017 |

| Research group (6 members, 3 faculties) writing grant applications/Funding (2 grant applications submitted) | 2017–2018 |

| Workshops on writing grant applications (24 researchers, 5 faculties) | 2018 |

| Research group (5 members, 3 faculties) writing on grant applications (2 grant applications submitted) | 2018 |

| Regular work meetings (research group finalized, 4 researchers, 3 faculties) | 2018 |

| Research group (4 members, 3 faculties) starting up autoethnographic work and article writing in progress | 2019 |

| Dr. Erin Cory reads and reviews our autoethnographic texts | 2019 |

| Workshop around Knowledge for Change (14 members, 3 faculties) | 2019 |

| Workshop around Position paper writing (10 researchers, 5 faculties) | 2019 |

| Position paper in progress (8 researchers, 5 faculties) | 2019 |

| Workshop around Position paper writing (7 researchers, 4 faculties) | 2020 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christensen, J.; Ekelund, N.; Melin, M.; Widén, P. The Beautiful Risk of Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Research. A Challenging Collaborative and Critical Approach toward Sustainable Learning Processes in Academic Profession. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094723

Christensen J, Ekelund N, Melin M, Widén P. The Beautiful Risk of Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Research. A Challenging Collaborative and Critical Approach toward Sustainable Learning Processes in Academic Profession. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094723

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristensen, Jonas, Nils Ekelund, Margareta Melin, and Pär Widén. 2021. "The Beautiful Risk of Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Research. A Challenging Collaborative and Critical Approach toward Sustainable Learning Processes in Academic Profession" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094723

APA StyleChristensen, J., Ekelund, N., Melin, M., & Widén, P. (2021). The Beautiful Risk of Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Research. A Challenging Collaborative and Critical Approach toward Sustainable Learning Processes in Academic Profession. Sustainability, 13(9), 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094723