Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Their Drivers of Change under Human-Dominated Pressure—The Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

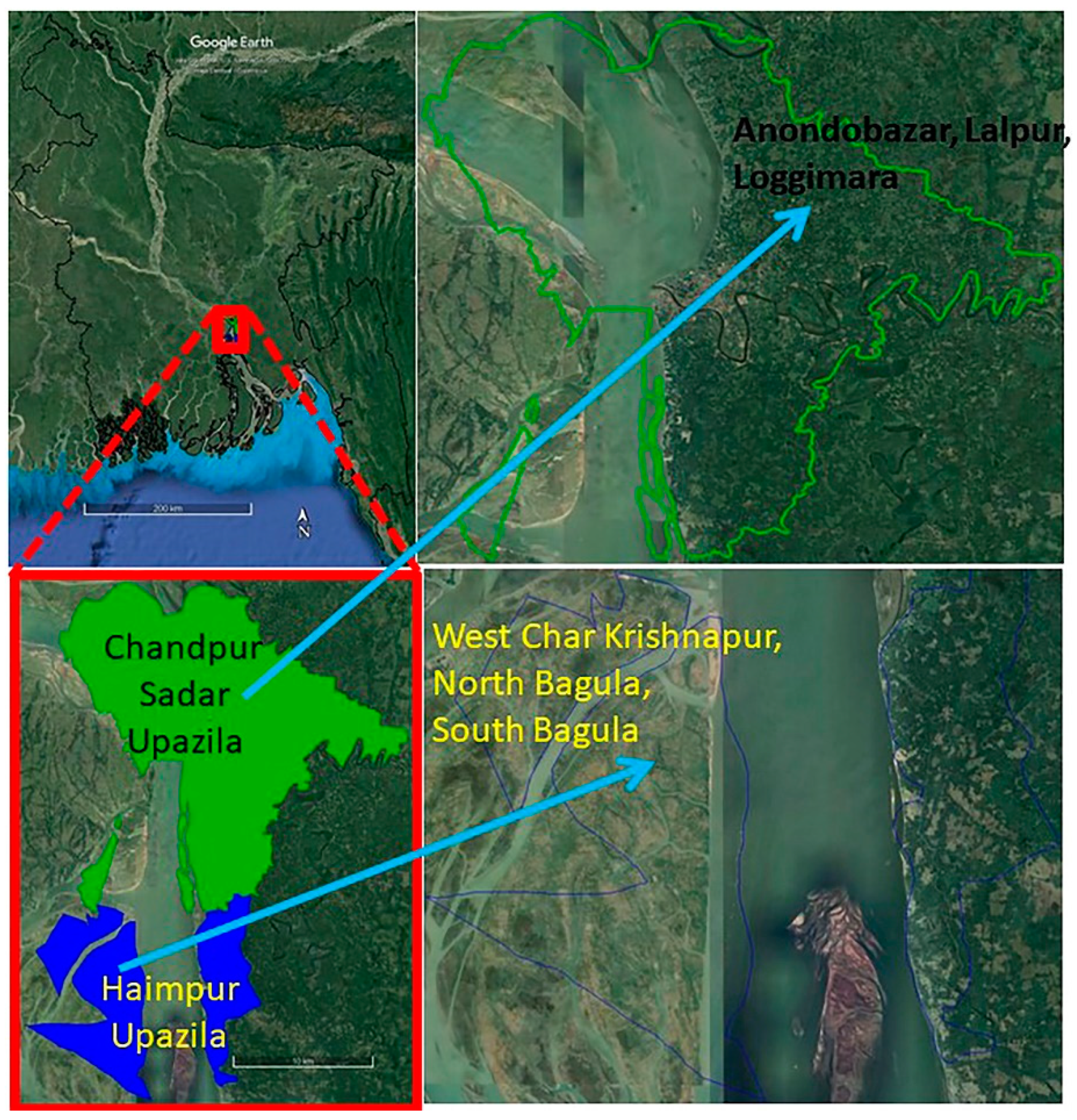

2.1. Selection of the Study Sites

2.2. Collecting Secondary Data

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Features of the Study Areas

3.2. Ecosystem Services in the Meghna River Estuarine Systems

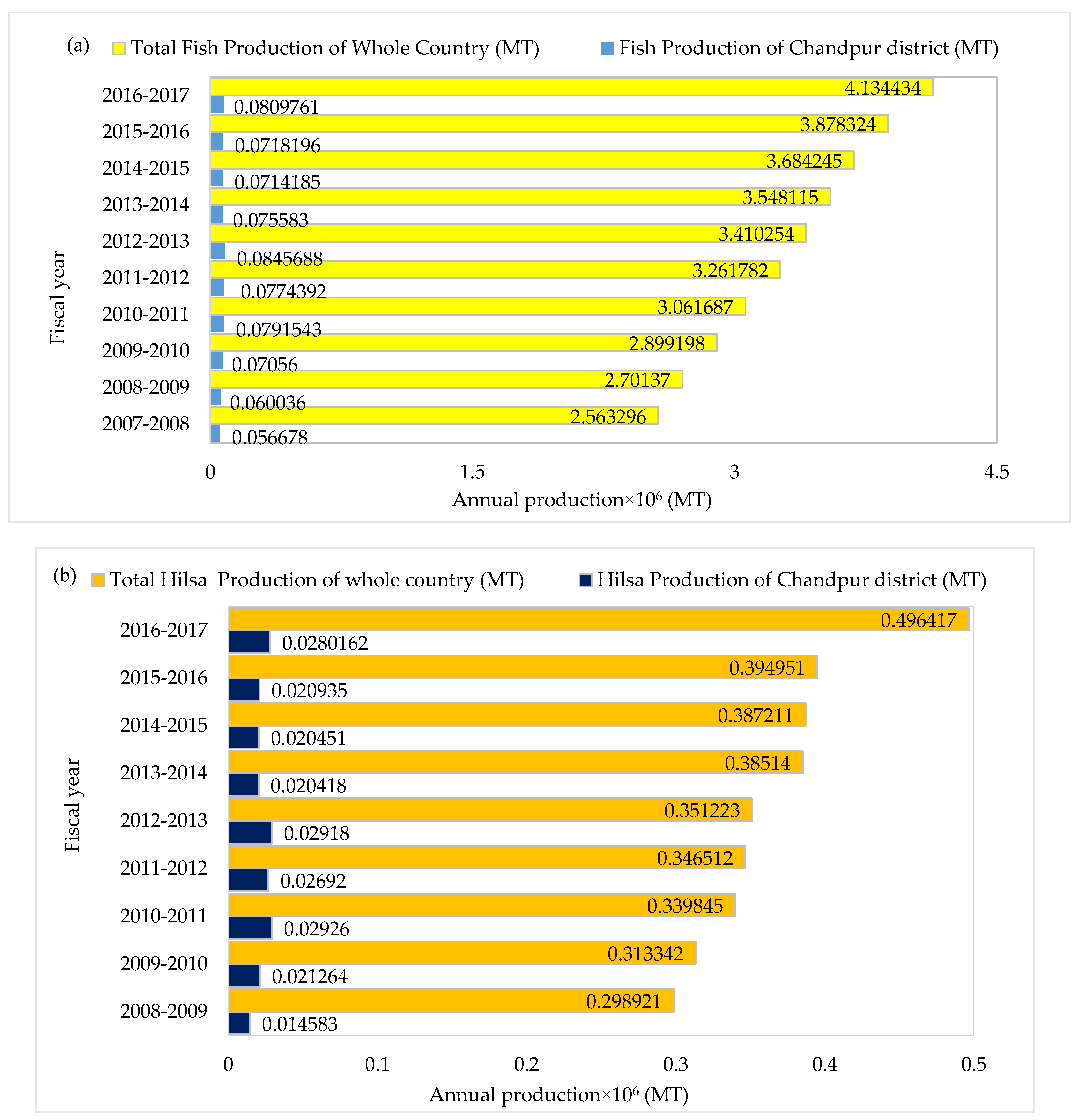

3.2.1. Provisioning Services

| ES Categories | Qualitative Description of the Ecosystem Services |

|---|---|

| Food (Capture fisheries) [32] |

|

| Food (Aquaculture) [33,34] |

|

| Source of Freshwater [35] |

|

| Fuel wood [36] |

|

| Timber [37] |

|

| Thatching materials [38] |

|

| Medicine [39,40,41] |

|

3.2.2. Regulatory and Maintenance Services

| ES Category | Qualitative Description of the ES |

|---|---|

| Feeding, breeding, and spawning ground |

|

| Pollution abatement |

|

| Water bioremediation |

|

| Protection from sedimentation |

|

| Protection from salt intrusion |

|

| Maintenance of primary and secondary production |

|

| Nutrient retention |

|

3.2.3. Cultural Services

| ES Category | Qualitative Description of the ES |

|---|---|

| Ecotourism |

|

| Recreational Place |

|

| Aesthetic value |

|

| Hilsha shad as a part of cultural heritage |

|

| Education, research, and knowledge |

|

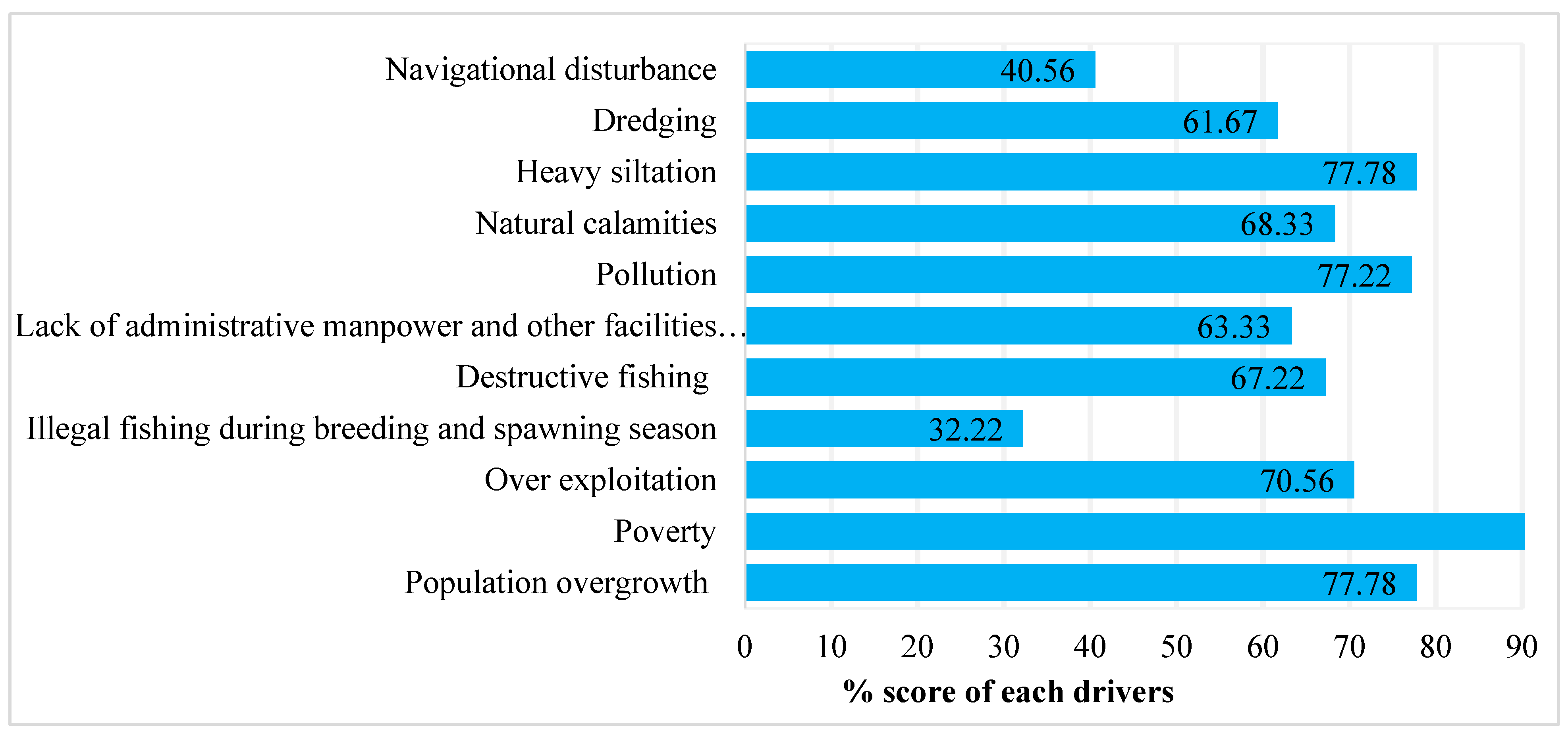

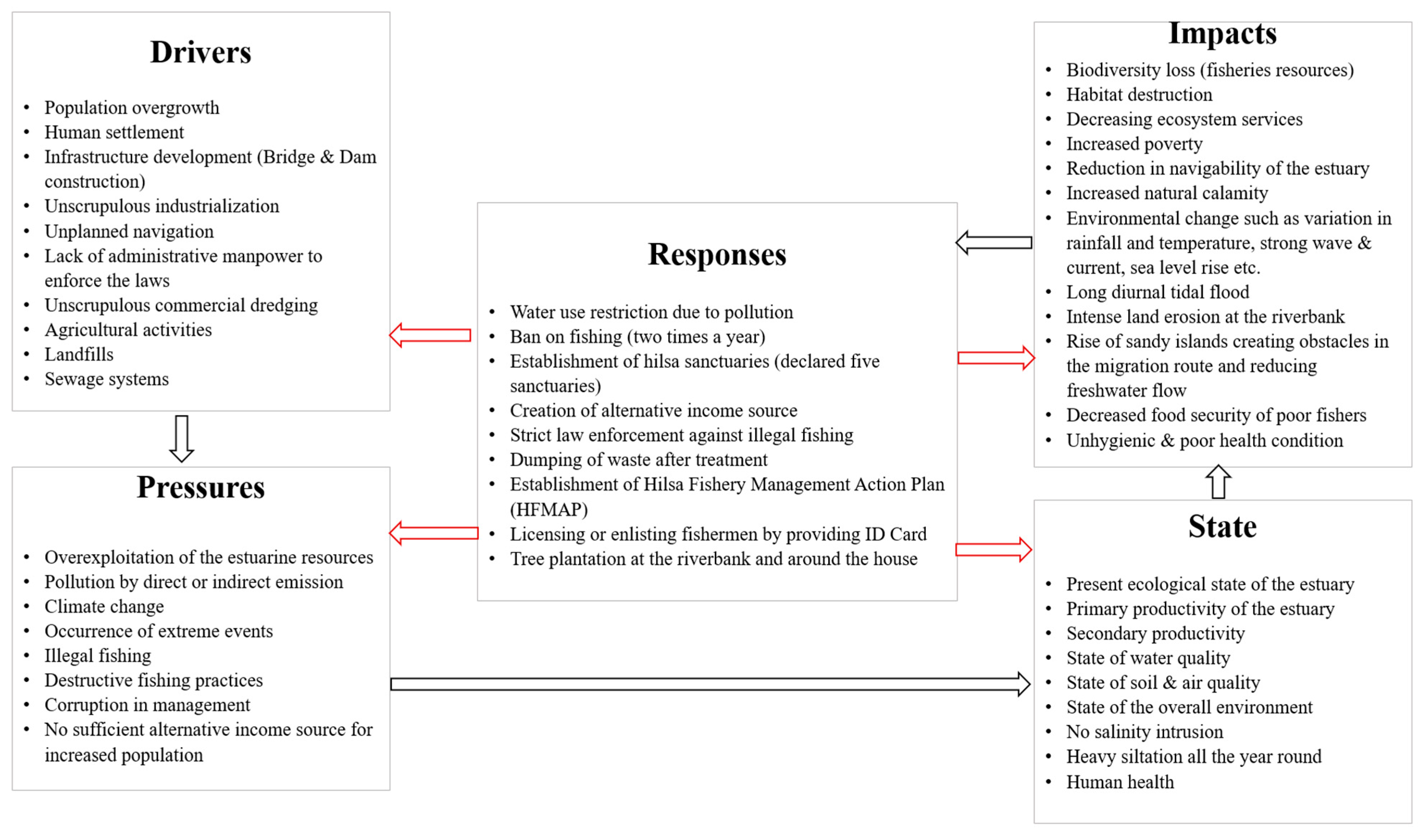

3.3. Drivers of Ecosystem Service Change from Community Perceptions

3.3.1. High Dependency on Natural Resources Due to the Lack of Alternative Income Opportunities

3.3.2. Unsustainable Practices

Overexploitation

Illegal Fishing during the Breeding and Spawning Season

Destructive Fishing

3.3.3. Lack of Administrative Workforce and Other Facilities to Enforce the Laws

Non-Compliance and Poor Law Enforcement

3.3.4. Pollution

3.3.5. Heavy Siltation

3.3.6. Dredging

3.3.7. Navigational Disturbance

3.3.8. Natural Calamities

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitra, A. Ecosystem Services of Mangroves: An Overview. In Mangrove Forests in India; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, B.; Turner, R.K.; Morling, P. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Brauman, K.A.; Van Der Meulen, S.; Brils, J. Ecosystem services and river basin management. In Risk-Informed Management of European River Basins; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangash, R.F.; Passuello, A.; Sanchez-Canales, M.; Terrado, M.; López, A.; Elorza, F.J.; Schuhmacher, M. Ecosystem services in Mediterranean river basin: Climate change impact on water provisioning and erosion control. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 458, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comino, E.; Bottero, M.; Pomarico, S.; Rosso, M. Exploring the environmental value of ecosystem services for a river basin through a spatial multicriteria analysis. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, Y. Study on change in value of ecosystem service function of Tarim River. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. The ecological value of stream restoration measures: An evaluation on ecosystem and target species scales. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 62, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.; De Jonge, V.N.; Neto, J.M.; Domingos, T.; Marques, J.C.; Patrício, J. Towards a DPSIR driven integration of ecological value, water uses and ecosystem services for estuarine systems. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 72, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Fang, Y.; Jawitz, J.W.; Yan, J.; Cui, B. River network connectivity and fish diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuvendal, M.; Elmqvist, T. Ecosystem services linking social and ecological systems: River brownification and the response of downstream stakeholders. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilvear, D.J.; Spray, C.J.; Casas-Mulet, R. River rehabilitation for the delivery of multiple ecosystem services at the river network scale. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 126, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, J.H.; Flotemersch, J.E.; Delong, M.D.; Casper, A.F.; Thoms, M.C.; Ballantyne, F.; Haase, C.S. Linking ecosystem services, rehabilitation, and river hydrogeomorphology. BioScience 2010, 60, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.K.; Straton, A. An economic assessment of the value of tropical river ecosystem services: Heterogeneous preferences among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Pal, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Schneider, P. Coastal Ecosystem Services, Social Equity, and Blue Growth: A Case Study from South-Eastern Bangladesh. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M. Catch Composition of Set Bag Net Fishery with Emphasis on the Population Dynamics of Two Commercial Important Fish Species from Chittagong Coastal Waters in the Bay of Bengal. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Marine Sciences, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S. Study of Catch Composition of Behundi Net (Set Bag Net) in Relation to Some Ecological Parameters in the Naaf River Estuary; Marine Fisheries Survey, Management and Development Project: Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ahammad, F. Catch Composition of Estuarine Set Bag Net (ISBN) in the Moheshkhali Channel of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Marine Sciences, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.R.; Wahab, M.A.; Belton, B. The Checklist of the Riverine Fishes of Bangladesh; The World Fish Center, Bangladesh and South. Asia Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DoF National Fish Week. Compendium Bangladesh: Department of Fisheries (DoF); Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, Government of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012.

- Rahman, A.K.A. Freshwater Fishes of Bangladesh, 2nd ed.; Zoological Society of Bangladesh, Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, M.M.H.; Hasan, M.M.; Bisshas, S.; Hossain, A.A.; Biswas, T.K. Fish biodiversity and their present conservation status in the Meghna River of Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish Aquat.Stud. 2017, 5, 446–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gaughan, D.J.; Neira, F.J.; Beckey, L.E.; Potter, I.C. Composition, seasonality and distribution of the ichthyoplankton in the lower Swan Estuary, south-western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1990, 41, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, A.K. Ichthyofaunal assemblages in estuaries: A South African case study. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1999, 9, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Das, N.G.; Chowdhury, M. Fisheries Management of the Naaf River; Coastal and Ocean Research Group of Bangladesh: Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2007; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Smeets, E.; Weterings, R. Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999; p. 19.

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Haimchar+Upazila,+Bangladesh/@23.0740053,90.5504763,32066m/data=! (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Chandpur,+Bangladesh/@23.2260115,90.6432363,8007m/data= (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Available online: http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Chandpur_District (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Shafi, M.; Quddus, M.M.A. Fisheries Resources of Bay of Bengal (Bonggoposagarer Matshaya Sampad); Bangla Academy: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1982. (In Bengali) [Google Scholar]

- Mozumder, M. Socio-Ecological Resilience of a Small-Scale Hilsa Shad (Tenualosa Ilisha) Fishery in the Gangetic River Systems of Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pravakar, P.; Sarker, B.S.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, M.B. Present status of fish farming and livelihood of fish farmers in Shahrasti upazila of Chandpur district, Bangladesh. Am.-Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2013, 13, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, B.; Karim, M.; Thilsted, S.; Collis, W.; Phillips, M. Review of Aquaculture and Fish Consumption in Bangladesh; The Worldfish Center: Peang, Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.L.; Islam, K.S. Assessment of Water Quality in Chandpur District of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2013, 1, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, M.D.; Al Rashid, H.; Shin, M.Y. Wood fuel use in the traditional cooking stoves in Bangladesh’s rural floodplain areas: A socio-environmental perspective. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.A.; Miah, M.A.Q.; Habib, M.A. Diversity of fruit and timber tree species in the coastal homesteads of southern Bangladesh. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Science 2013, 39, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mehvar, S.; Filatova, T.; Sarker, M.H.; Dastgheib, A.; Ranasinghe, R. Climate change-driven losses in ecosystem services of coastal wetlands: A case study in the West coast of Bangladesh. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 169, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Rashid, M.M.O.; Millat, M.S.; & Rashid, M.M. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by traditional health practitioners and indigenous people in different districts of Chittagong division, Bangladesh. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.S.H.; Koike, M.; Muhammed, N.; Halim, M.A.; Saha, N.; Kobayashi, H. Use of plants in healthcare: A traditional ethno-medicinal practice in rural areas of southeastern Bangladesh. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag. 2009, 5, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollik, A.H.; Hassan, A.I.; Paul, T.K.; Sintaha, M.; Khaleque, H.N.; Noor, F.A.; Nahar, A.; Seraj, S.; Jahan, R.; Chowdhury, M.H.; et al. A survey of medicinal plant usage by folk medicinal practitioners in two villages by the Rupsha River in Bagerhat district, Bangladesh. Am. -Eurasian J. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 4, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- DOF. National Fish Week Compendium; Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, Government of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017; p. 160. (In Bengali)

- Shamsuzzaman, M.M.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Mitu, S.J.; Ahamad, A.F.; Bhyuian, M.S. The economic contribution of fish and fish trade in Bangladesh. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DoF National Fish Week 2018 Compendium; Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018; p. 160.

- Mohammed, E.Y.; Wahab, M.A. Direct Economic Incentives for Sustainable Fisheries Management: The Case of Hilsa Conservation in Bangladesh; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Benstead, J.P.; March, J.G.; Pringle, C.M. Estuarine larval development and upstream post-larval migration of freshwater shrimps in two tropical rivers of Puerto Rico. Biotropica 2000, 32, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstead, J.P.; March, J.G.; Pringle, C.M.; Scatena, F.N. Effects of a low-head dam and water abstraction on migratory tropical stream biota. Ecol. Appl. 1999, 9, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A. Goldar, M.I. 2016: Hilsa Fish Management Planning; Eco-fish Bangladesh Project, Financed by USAID; The World Fish Center, Bangladesh and South. Asia Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Mohammed, E.Y.; Ali, L. Economic Incentives for Sustainable Hilsa Fish Management in Bangladesh: Institutional Framework, Gaps and Capacity-Strengthening Strategy and Action Plan; Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, F.; Azam, M.H.; Mahboob-Ul-Kabir, M. Residual flow in the Meghna Estuary on the coastline of Bangladesh. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2002, 55, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Chuenpagdee, R. Nomadic fishers in the hilsa sanctuary of Bangladesh: The importance of social and cultural values for well-being and sustainability. In Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2018; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mia, M.S.; Yeasmin, F.; Nesa, N.U.; Kafi, M.F.H.; Miah, M.I.; Haq, M.S. Assessment and monitoring fish biodiversity of Meghna river in Bangladesh. Int. J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2015, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen, A.; Rintamäki, P.; Jokela, J.; Valtonen, E.T. Increasing water temperature and disease risks in aquatic systems: Climate change increases the risk of some, but not all, diseases. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Evans, A.E.; Chadwick, M. Methodology for performance analysis of textile effluent treatment plants in Bangladesh. Chem. Eng. Res. Bull. 2009, 13, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Das, N.G.; Sarker, S.; Rahaman, M.Z. Fish diversity and habitat relationship with environmental variables at Meghna river estuary, Bangladesh. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2012, 38, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzoga, M.; Simatele, D.M.; Munga, C.; Yonge, S. Application of the DPSIR Framework to Coastal and Marine Fisheries Management in Kenya. Ocean Sci. J. 2020, 55, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R.; Wingard, P.M.; Yorty, S.C.; Thompson, M.C.; Jensen, N.K.; Roberson, J. Applying DPSIR to sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewison, R.L.; Rudd, M.A.; Al-Hayek, W.; Baldwin, C.; Beger, M.; Lieske, S.N.; Jones, C.; Satumanatpanh, S.; Junchompoo, C.; Hines, E. How the DPSIR framework can be used for structuring problems and facilitating empirical research in coastal systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 56, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekmohammadi, B.; Jahanishakib, F. Vulnerability assessment of wetland landscape ecosystem services using driver-pressure-state-impact-response (DPSIR) model. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 82, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.M.; Piscopo, A.N.; Chintala, M.M.; Gleason, T.R.; Berry, W. Developing qualitative ecosystem service relationships with the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response framework: A case study on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 84, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geographical Features of the Study Areas | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chandpur Sadar Upazila * | Haimchar Upazila | |

| Administrative jurisdiction | Chandpur District | Chandpur District |

| Location | 23°12′50.04″ N 90°38′9.96″ E | 23°04′0.12″ N 90°38′15.00″ E |

| Study site covered | 19 km | 12 km |

| Main rivers/estuary | Meghna and Dakota | Meghna |

| Study sites population density | 1106/km2 | 628/km2 |

| Union Parishad | 14 | 6 |

| Fisheries organization (Govt.) | Fishery diploma institute, Fishery training institute, BFRI (riverine station) | None |

| Ecotourism site | Boro Station Mohona Park | No |

| Cultural heritage | Hilsha | Hilsha |

| Coastal aquaculture | Not significant | Not significant |

| Authorized responsible bodies of the fisheries sector | Upazilla Fisheries Officer; Upazila Nirbahi Officer, Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute scientists, Magistrate, Police, Navy, Coastguard | Upazilla Fisheries Officer; Upazila Nirbahi Officer, Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute scientists, Magistrate, Police, Navy, Coastguard |

| District (Upazila) | Study Sites | The Distance of Each Village from Upazila (km) | Sample Size (Number) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union | Village | II | FGD | KII | ||

| Chandpur (Chandpur Sadar) | Tarpurchandi | Anondobazar | 5 | 20 | 1 | 6 |

| Bishnupur | Lalpur | 20 | 20 | 2 | 6 | |

| Rajrajeshwar | Loggimara | 10 | 20 | 2 | 6 | |

| Chandpur (Haimchar) | South Algi Durgapur | West Char Krishnapur | 5 | 20 | 1 | 6 |

| Char Bhairabhi | North Bagula | 15 | 20 | 2 | 6 | |

| South Bagula | 5 | 20 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Total | 5 | 6 | 120 | 10 | 36 | |

| Sl. | Landing Centers (Name of the Place) | Location (GPS) |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Lalpur Machghat, Bishnupur | 23°17′56″ N; 90°39′26″ E |

| 02 | Anando Bazar Machghat, Tarpurchandi | 23°14′74″ N; 90°39′71″ E |

| 03 | Boro Station Landing Center, Chandpur | 23°13′81″ N; 90°38′52″ E |

| 04 | Katakhali Machghat, Lamchori, Uttor Algi | 23°06′41″ N; 90°38′71″ E |

| 05 | Telir Mor/Kalikhola Machghat, Dakshin Algi | 23°05′31″ N; 90°38′55 ″E |

| 06 | Haim Char Machghat, Uttar Char Bhairobi | 23°04′21″ N; 90°39′47″ E |

| 07 | Katakhal Machghat, Jaliar Char, Chorbhairobi | 23°01′0.1″ N; 90°39′35″ E |

| 08 | Habi Gazir Kandi Machghat, Molla Kandi, Haimchar | 23°03′0.9″ N; 90°36′30″ E |

| Characteristics | Categories | Chandpur Sadar (n = 65) | Haimchar (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| Age | <20 | 1 (1.54) | 0 |

| 21–40 | 26 (40) | 14 (25.45) | |

| 41–60 | 28 (43.08) | 28 (50.91) | |

| >60 | 10 (15.38) | 13 (23.64) | |

| Main occupation | Fishery | Fishery | |

| The trend of gender for fishing | Male | Male | |

| Education | Illiterate | 50 (76.92) | 38 (69.09) |

| Can sign only | 10 (15.38) | 17 (30.91) | |

| Primary | 5 (7.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Religion | Hinduism | 6 (9.23) | 0 (0) |

| Muslim | 59 (90.77) | 55 (100) | |

| Marital status | Married | 60 (92.3) | 55 (100) |

| Unmarried | 5 (7.69) | 0 (0) | |

| Housing Structure | |||

| Roofing materials | Tin shade (iron sheet) | 65 (100) | 55 (100) |

| Wall | Thatch | 3 (4.62) | 4 (7.27) |

| Wood and Bamboo | 1 (1.54) | 0 | |

| Tin (iron sheet) | 61 (93.85) | 51 (92.73) | |

| Floor | Earthen | 56 (86.15) | 55 (100) |

| Wood | 0 | 0 | |

| Cemented | 9 (13.85) | 0 | |

| Ownership of the house | Owned | 59 (90.77) | 50 (90.91) |

| Leased | 6 (9.23) | 5 (9.09) | |

| Alternative occupation | Day laboring | 8 (12.31) | |

| Agriculture | 9 (13.85) | ||

| Rickshaw pulling | 0 | 4 (7.27) | |

| Tailor | 3 (4.62) | 6 (10.91) | |

| Rearing domestic animals | 3 (4.62) | 2 (3.64) | |

| No other way of income | 42 (64.62) | 43 (78.18) | |

| Income (USD) | 0–58.94 | 5 (7.69) | 14 (25.45) |

| 58.95–117.89 | 44 (67.69) | 34 (61.82) | |

| 117.90–176.83 | 16 (24.62) | 7 (12.73) | |

| Electricity | Available except Rajrajeswar | Available | |

| Having fishing boats and gear | Yes | 25 (28.46) | 20 (36.36) |

| No | 40 (61.54) | 35 (63.64) | |

| Road & Transport | Well infrastructure of roads except for Rajrajeswar union. | Both road and water transportation | |

| Dependency on estuary | High (60–80%) | Very high (>80%) |

| Developmental Achievement and Activities | Quantity/Amount |

|---|---|

| Hilsa production increased | 17,550.5 MT |

| Fisheries production increased | 38,668 MT |

| Fish fry stocking in open water bodies (to increase fish production of Meghna river/ Meghna river estuary) | 43.84 MT |

| Establishment of nursery grounds in different beels | 28 beels |

| Construction of exhibition pond (modern technology-based aquaculture) | 403 ponds |

| Giving training to fish farmers (modern technology-based aquaculture) | 21,760 fishermen |

| Successful enforcement of fisheries law/act to conserve mainly Hilsa fishery as well as other fishes | 7435 |

| Construction of floating cages for cage culture in Dakatia river | 1962 cages |

| Pan construction | 35 pans |

| Providing ID card to fishers to enlist them | 51,190 fishermen |

| Legal mesh sized fishing net providing to stop the use of gill net or current jal | 13,570 fishermen |

| To create alternative income source No. of distributed goats & cows | 1378, 402 (respectively) |

| Sewing machines & Vans | 3794, 250 (respectively) |

| Mobile application to stay connected with fishing communities and trace their activities | 369 fishermen |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miah, M.Y.; Hossain, M.M.; Schneider, P.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Mitu, S.J.; Shamsuzzaman, M.M. Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Their Drivers of Change under Human-Dominated Pressure—The Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084458

Miah MY, Hossain MM, Schneider P, Mozumder MMH, Mitu SJ, Shamsuzzaman MM. Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Their Drivers of Change under Human-Dominated Pressure—The Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084458

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiah, Mohammad Yusuf, Mohammad Mosarof Hossain, Petra Schneider, Mohammad Mojibul Hoque Mozumder, Sabrina Jannat Mitu, and Md. Mostafa Shamsuzzaman. 2021. "Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Their Drivers of Change under Human-Dominated Pressure—The Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084458

APA StyleMiah, M. Y., Hossain, M. M., Schneider, P., Mozumder, M. M. H., Mitu, S. J., & Shamsuzzaman, M. M. (2021). Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Their Drivers of Change under Human-Dominated Pressure—The Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh. Sustainability, 13(8), 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084458