Local Community Experience as an Anchor Sustaining Reorientation Processes during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The World Café Methodology

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

- How has the way of living in urban spaces in your neighborhood changed due to COVID-19?

- How have neighbors in your neighborhood kept in touch since the COVID-19 outbreak?

- How would you favor the social meanings and dimensions of common spaces in your neighborhood?

- How would you modify urban spaces in your neighborhood to enhance their livability?

- Whom would you involve in order to implement these changes?

4. Results

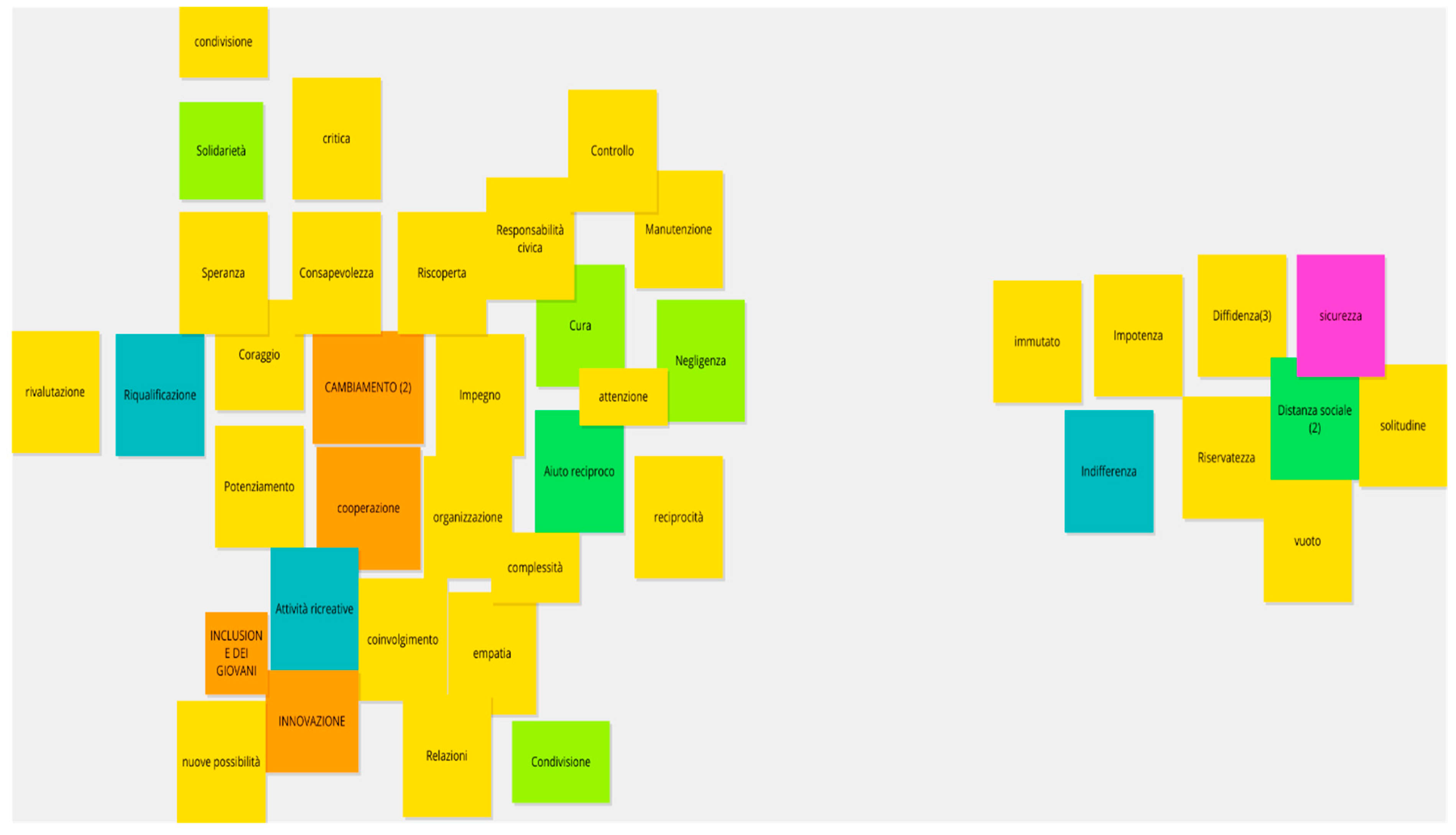

4.1. Neighborhood Experience under COVID-19-Related Measures

“The pandemic did not change how I live in my neighborhood. Even before the pandemic, I did not visit it that much. When I was younger, I was more participatory for sure.”

“Even before the pandemic, I did not hang out in my neighborhood, so nothing has changed. I admit that during my childhood I was more involved in it, but my interest waned when I started high school in another city.”

“Since before the COVID-19 outbreak and the related lockdown, I have lived in my neighborhood less and less, because as I have grown up, my meeting places have become others. Indeed, one consequence of living in a small village with few meeting spots and attending first high school and then university in the nearby city was experiencing the places in the city center more and those in my neighborhood much less.”

“The few times I find myself walking through the streets of my neighborhood, I dwell much more on its beauties, especially during Christmas time.”

“Before the lockdown, I did not hang out in my neighborhood, because I tended to move to other neighborhoods; now, due to the current restrictions and not being able to move to other neighborhoods, I am rediscovering some of its areas, even if in a limited way.”

“Before the COVID-19 outbreak, we certainly weakly lived in our neighborhoods and frequently tended to move away. This led us to estrange ourselves from our places of belonging, which have always offered few initiatives for young people, and to move to places where the nightlife was guaranteed. During this pandemic, however, as we found ourselves unable to move, we have been forced to experience our neighborhoods/towns, rediscovering the problems and strengths of the community and, consequently, getting closer to it.”

“The way I live in my neighborhood has changed drastically. I have never fully experienced the place where I live—except when I was a child—and the causes are different: Growing up, I have lost interest in going to the same places, I have lost the friends I had as a child, I have met people from different backgrounds. But now my neighborhood is the only place where I can go out, have fun, and be in company from a distance. I, therefore, changed my way of experiencing and seeing it, going out at least once a day if only to take a walk.”

4.2. COVID-19 Effects on Local Relationships

“The time of the lockdown […] brought me closer to my neighbors, with whom I found myself talking much more often. I got to know them a lot more in those three months than in the last 20 years.”

“The relationship with my neighbors has improved a lot. Specifically, I made friends with my neighbor’s daughter, who is almost my age. Together we took long walks in our neighborhood and long chats at the window, each one in their own home. To date, we are real friends, we hear from each other regularly, and sometimes we even go out together.”

“Our relationship has certainly changed, because if before it was limited to greetings and the usual pleasantries, now maybe we are more united, because we are in this together, and even if we cannot physically meet, we hear each other on the phone more frequently.”

“Over the years, there has always been a relationship of ups and downs that has stabilized clearly following the pandemic, where there has been greater mutual availability and a pleasant exchange of gestures.”

“During the pandemic, we certainly tried to be more united and to help each other as much as possible. Everyone tried in their own small way to be available for others, for example, avoiding letting the elderly out—since they are a group at greater risk of contagion—and making purchases online and in-person for them. […] Now we know we can count on each other in case of need, especially after some emergencies.”

“The relationships with my neighbors have deteriorated somewhat. They are quite annoying people, and during the lockdown, their presence was felt—and not a little.”

“The relationships with my neighbors have never been very intimate, but in recent months they have particularly cooled down because each of us sees the others as a possible danger, as the ones who can transmit the virus to us and compromise both ourselves and our households.”

“There is practically no relationship with neighbors anymore, as you always try to avoid any kind of contact, both for your own health and others’.”

“Before the COVID-19 outbreak, we stopped even for a few minutes to chat in the street; now, this happens from the balconies or it doesn’t happen at all, and the conversation in person is preferred over the telephone, so you feel a little distance.”

“These circumstances of uncertainty inevitably lead people to distance themselves from others, they are insecure of the slightest contact with each other, for the matter of preventing their own health.”

“By now, reciprocity is drastically lacking due to social distance, a distance that today is almost synonymous with safety, whose wake is a cold indifference, but which at the same time brings a deep sense of emptiness, loneliness, powerlessness.”

“The places in my neighborhood that were most populated before the COVID-19 outbreak are currently semi-deserted.”

“The way we live in our neighborhood has changed, especially in the activities that we can carry out today. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, local common places were lived in for the most part with friends, while today for the most part they are frequented in a solitary way or with someone belonging to the family unit at most.”

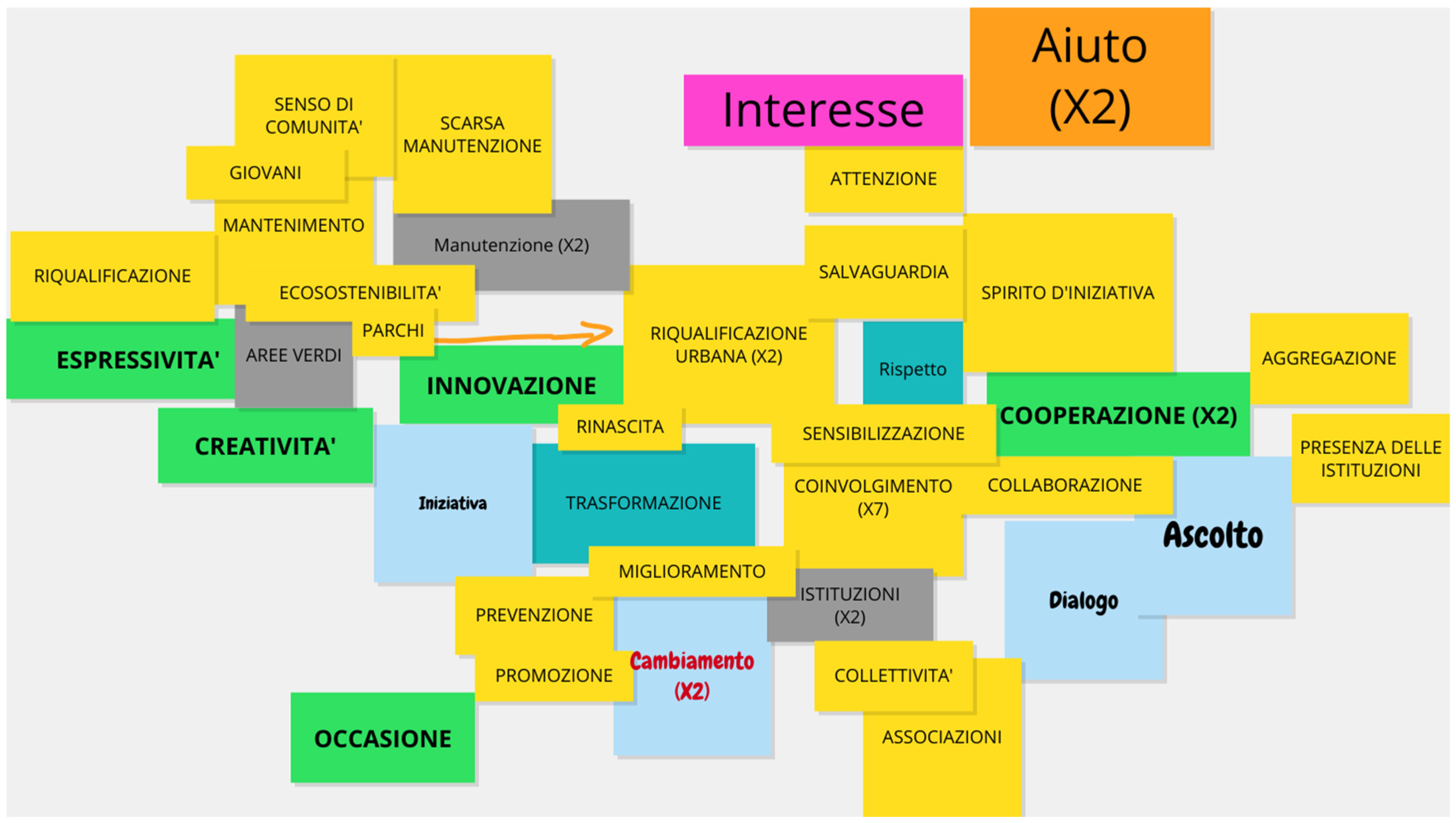

4.3. Desire for Reappropriation

“In my neighborhood, there are several spaces that could potentially favor the social dimensions; however, due to the lack of controls and to the little interest of the community, these areas are abandoned and over time have become unusable.”

“It would be useful to reuse the unused spaces of the neighborhood by creating solutions that encourage the participation of the inhabitants of the neighborhood and beyond.”

“I would definitely add something to the park in my municipality, which is very beautiful and very large but also really empty. It would be nice to add some benches to enjoy the view and maybe a few merry-go-rounds for families who go out with their children, but something more should be added for young people too.”

“I would use the green areas as key points of the neighborhood, redeveloping them and also organizing events for young people in these places, in order to repopulate the neighborhood with young people.”

“In my opinion, more initiatives could be implemented for young citizens, such as events and sports games that can improve the territory and give greater opportunities of knowledge both of the neighborhood and among peers.”

“I would promote the organization of cultural events (art exhibitions, presentation of books, concerts, theatrical performances).”

“I would organize more festivals and feasts, social and cultural events, to increase the sense of community and the culture within the neighborhood.”

“More open-air spaces, especially parks, which under circumstances like the one we are experiencing can allow people to relate face-to-face safely.”

“A place that you can attend even in periods like the present one and therefore where it is possible to respect the safety distance but at the same time meet people we have not seen for months.”

“I would add a meeting place that purely concerns the neighborhood and the people who live there, because all the available meeting places concern all the people of the municipality and also people who come from other municipalities. Instead, we would need something that makes us feel we belong to this particular neighborhood and that makes us want to have something to do with those who live there.”

“We would need meeting places that relate purely to the neighborhood and/or municipality of residence and all the people who live there, in order to increase our sense of belonging to a community and motivate us to more assiduously go out in our own town.”

“A fundamental step is to create initiatives that bring the population closer to their own town; certainly, feeling an active part of a community invites them to more assiduously live in their neighborhood.”

“I would bring back to life associations such as ACR (Azione Cattolica Ragazzi, Catholic Action for Youths), or meetings of young people who were in church, also discussing topics not necessarily concerning the latter, or I would set up meetings to exchange ideas or books.”

“It would be critical to carve out moments of social contact for the community by organizing social events, including cultural ones; in this way, we believe it could be possible not only to strengthen social ties, but also to have more activities available for young people.”

4.4. Citizens’ Power to Improve Their Neighborhood

“Certainly, many of us need a change, something that makes us feel alive and active in the communities where we live.”

“Making such a change is not easy. For this reason, I would involve as many people as possible. First, it would be right to involve the relevant institutions of the neighborhood, such as schools with children and teachers, but not only. I would also ask my neighborhood church for help, as it has always tried to help, and I know it would not hold back. Obviously, I would also bring the municipality into the question, asking for the support of many workers of different categories, such as having more and more active ecological operators in very busy and dirty areas. Finally, I would seek support from my friends and peers by trying to raise awareness about the importance of common spaces and mutual respect.”

“To activate a change, there must be dialogue between institutions and community members first, so that there would be a citizens’ initiative and active involvement.”

“We need to understand how to actively change something that we have thought would always remain the same until now: Being a citizen also means taking action to make things more advantageous not only for oneself, but also for those who will follow. Consequently, we think it would be nice to be able to cooperate with those who can concretely carry out these changes. There are few opportunities where we live—mostly clubs—and it would be good to be able to change this through everyone’s commitment.”

“Only through taking care of, controlling, and maintaining shared spaces, aware of our sense of civic responsibility, can we courageously obtain their revaluation, redevelopment, and enhancement, but also open the scenario to new possibilities and innovations with the introduction of recreational activities that could allow the inclusion of young people who, through knowing each other, could establish relationships and new friendships within the same neighborhood.”

“I would focus on the involvement of young people, precisely because they would become the main users of those spaces; in general, I would tend to involve the entire community in order to be able to strengthen local bonds.”

“We would turn to municipal bodies and mayors, as they are those who have the technical skills and the power to be able to implement these changes.”

“We perceive a strong sense of powerlessness, almost as if each of us is just a passive subject who is powerlessly subjected to the future of these continuous events and changes.”

“However, all our proposals seemed a utopia more than anything else to us: Beyond the COVID-19 outburst, there are many people who remain indifferent to the everyday life that surrounds them, and who therefore commit themselves to redeveloping and rediscovering their neighborhood and community very little or not at all, moving further and further away from it.”

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministero della Salute. Some Simple Recommendations to Contain the Coronavirus Infection. 2020. Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_opuscoliPoster_443_0_alleg.jpg (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri. Ulteriori Disposizioni Attuative del Decreto-Legge 25 marzo 2020, N. 19, Convertito, con Modificazioni, dalla Legge 25 Maggio 2020, N. 35, Recante “Misure Urgenti per Fronteggiare l’Emergenza Epidemiologica da COVID-19”, e del Decreto-Legge 16 Maggio 2020, N. 33, Convertito, con Modificazioni, dalla Legge 14 Luglio 2020, N. 74, Recante “Ulteriori Misure Urgenti per Fronteggiare l’Emergenza Epidemiologica da COVID-19” (20A06109). Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto?id=76993&completo=true (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Lavie, C.J. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursano, R.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; Weisaeth, L.; Raphael, B. Individual and community responses to disasters. In Textbook of Disaster Psychiatry; Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Weisaeth, L., Raphael, B., Eds.; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, H.; Chen, J.H.; Xu, Y.F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, S.B. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, F.; Procentese, F. Being Involved in the Neighborhood through People-Nearby Applications: A Study Deepening Their Social and Community-Related Uses, Face-to-Face Meetings among Users, and Local Community Experience. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. 2020, 2730. Paper 5. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2730/paper5.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Gatti, F.; Procentese, F. Open Neighborhoods, Sense of Community, and Instagram Use: Disentangling Modern Local Community Experience through a Multilevel Path Analysis with a Multiple Informant Approach. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 27, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Ratiu, E.; Fleury-Bahi, G. Appropriation and interpersonal relationships: From dwelling to city through the neighborhood. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. Measuring the public realm: A preliminary assessment of the link between public space and sense of community. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2000, 17, 344–360. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, L.; Frank, L.D.; Giles-Corti, B. Sense of community and its relationship with walking and neighborhood design. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M. Streets Apart: Does Social Capital Vary with Neighbourhood Design? Urban Stud. Res. 2012, 2012, 507503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cattell, V.; Dines, N.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S. Mingling, observing, and lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health Place 2008, 14, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Tartaglia, S.; Fedi, A.; Greganti, K. Image of neighborhood, self-image and sense of community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, L.M.F.; Balzarotti, R.M.; Semprebon, G.; Camerin, F. New Healthy Settlements Responding to Pandemic Outbreaks. Plan J. 2021, 5, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Buffoli, M.; Appolloni, L.; Signorelli, C.; Fara, G.M.; D’Alessandro, D. COVID-19 and cities: From urban health strategies to the pandemic challenge. A decalogue of public health opportunities. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; van den Bosch, C.K.; Litt, J.S.; Mawani, V.; McCall, M.K.; Orellana, A.; Oscilowicz, E.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities Health 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.J.; Christiana, R.W.; Gustat, J. Recommendations for keeping parks and green space accessible for mental and physical health during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. We’ll need to reopen our cities. But not without making changes first. Bloomberg CityLab. 27 March 2020. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-27/how-to-adapt-cities-to-reopen-amid-coronavirus (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Null, S.; Smith, H. COVID-19 Could Affect Cities for Years. Here Are 4 Ways They’re Coping Now. TheCityFix: World Resource Institute (WRI). 2020. Available online: https://thecityfix.com/blog/covid-19-affect-cities-years-4-ways-theyre-coping-now-schuyler-null-hillary-smith/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Roberts, D. How to Make a City Livable During Lockdown. Vox. 22 April 2020. Available online: https://www.vox.com/cities-and-urbanism/2020/4/13/21218759/coronavirus-cities-lockdown-covid-19-brent-toderian (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Van der Berg, R. How Will COVID-19 Affect Urban Planning? TheCityFix: World Resource Institute (WRI). 2020. Available online: https://thecityfix.com/blog/will-covid-19-affect-urban-planning-rogier-van-den-berg/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- De Rosa, A.S.; Mannarini, T. COVID-19 as an “invisible other” and socio-spatial distancing within a one-metre individual bubble. Urban Design Int. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, B. When Disaster Strikes; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chamlee-Wright, E.; Storr, V.H. “There’s no place like new orleans”: Sense of place and community recovery in the ninth ward after hurricane katrina. J. Urban Aff. 2009, 31, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.S.; Cartlidge, M.R. Place attachment among retirees in Greensburg, Kansas. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 101, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, G. ‘Solastalgia’. A new concept in health and identity. PAN Philos. Act. Nat. 2005, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson, A.R. Understanding mass panic and other collective responses to threat and disaster. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2005, 68, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mawson, A.R. Mass Panic and Social Attachment: The Dynamics of Human Behavior; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, A.; Andrey, J. The influence of previous disaster experience and sociodemographics on protective behaviors during two successive tornado events. Weather Clim. Soc. 2014, 6, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresi, G.; Procentese, F.; Gattino, S.; Tzankova, I.; Gatti, F.; Compare, C.; Marzana, D.; Mannarini, T.; Fedi, A.; Marta, E.; et al. Prosocial behaviours under collective quarantine conditions. A latent class analysis study during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Daniel, M.; Linnan, L.; Campbell, M.; Benedict, S.; Meier, A. After Hurricane Floyd passed: Investigating the social determinants of disaster preparedness and recovery. Fam. Community Health 2004, 27, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilson, L.B. The disaster victim community: Part of the solution, not the problem. Rev. Policy Res. 1985, 4, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J. Catastrophe Compassion: Understanding and Extending Prosociality under Crisis. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.S.; Perry, K.M.E. Like a fish out of water: Reconsidering disaster recovery and the role of place and social capital in community disaster resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyers, W.; Goossens, L.; Vansant, I.; Moors, E. A Structural Model of Autonomy in Middle and Late Adolescence: Connectedness, Separation, Detachment, and Agency. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Di Napoli, I.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. Close family bonds and community distrust. The complex emotional experience of a young generation from Southern Italy. J. Youth Stud. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. A Resource Guide for Hosting Conversations that Matter at the World Café; Whole Systems Associates: Burnsville, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Isaacs, D. The World Café: Shaping our Futures through Conversations That Matter; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schieffer, A.; Isaacs, D.; Gyllenpalm, B. The world café: Part 1. World Bus. Acad. 2004, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt, V. Working in the café: Lessons in group dialogue. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Homer, K.; Isaacs, D. The Change Handbook; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzenegger, K. Evaluation Café. 2010. Available online: http://www.weitzenegger.de/content/?page_id=1781 (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Estacio, E.V.; Karic, T. The World Café: An innovative method to facilitate reflections on internationalisation in higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joffe, H. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Harper, D., Thompson, A.R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Crisi dei giovani e sfiducia nei contesti locali di appartenenza. Un approccio di psicologia ecologica. In Krise als Chance aus Historischer und Aktueller Perspektive (Crisi e Possibilità—Prospettive Storiche E Attuali); Schafroth, E., Schwarzer, C., Conte, D., Eds.; Athena Verlag: Oberhausen, Germany, 2010; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Carli, R. Le Culture Giovanili; Francoangeli: Milano, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F.; Scotto di Luzio, S.; Natale, A. Convivenza responsabile: Quali i significati attribuiti nelle comunità di appartenenza? Psicologia Comunità 2011, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating sense of community: The role of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, A.; Grek-Martin, J. “Now we understand what community really means”: Reconceptualizing the role of sense of place in the disaster recovery process. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C.; Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. J. Community Appl. Social Psychol. 2007, 17, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P.; Pretty, G. Determinants of subjective quality of life among rural adolescents: A developmental perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Pirini, C.; Keyes, C.; Joshanloo, M.; Rostami, R.; Nosratabadi, M. Social participation, sense of community and social well-being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Gatti, F. Senso di Convivenza Responsabile: Quale Ruolo nella Relazione tra Partecipazione e Benessere Sociale? Psicologia Soc. 2019, 14, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; De Carlo, F.; Gatti, F. Civic Engagement within the Local Community and Sense of Responsible Togetherness. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 26, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Gargiulo, A.; Gatti, F. Local Groups’ Actions to Develop A Sense of Responsible Togetherness. Psicologia Comunità 2020, 1, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, J. Social Networks and Social Influences in Adolescence; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hughey, J.; Speer, P.W.; Peterson, N.A. Sense of community in community organizations: Structure and evidence of validity. J. Community Psychol. 1999, 27, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Fedi, A.; Trippetti, S. Public involvement: How to encourage citizen participation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 20, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmer, M.L. Citizen participation in neighborhood organizations and its relationship to volunteers’ self-and collective efficacy and sense of community. Social Work Res. 2007, 31, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Gatti, F.; Falanga, A. Sense of responsible togetherness, sense of community and participation: Looking at the relationships in a university campus. Hum. Aff. 2019, 29, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. A conceptual framework to enhance community resilience using social capital. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2017, 45, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisæth, L. The stressors and the post-traumatic stress syndrome after an industrial disaster. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1989, 80, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Stevens, E.; Light, J.M. The relationship of sense of community and trust to hope. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raphael, B. Crowds and other collectives: Complexities of human behaviors in mass emergencies. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2005, 68, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 1. Neighborhood experience under COVID-19-related measures | Indifference to local dimensions |

| “Forced” rediscovery of local dimensions | |

| 2. COVID-19 effects on local relationships | Polarization of the relationship with neighbors |

| Distance from other community members and fear of getting infected | |

| 3. Desire for reappropriation | Desire to exploit the previously forsaken urban open-air spaces |

| Desire for opportunities for community ties and encounters | |

| Denial of COVID-19 outbreak | |

| 4. Citizens’ power to improve their neighborhood | Sense of powerlessness |

| Delegation | |

| Involvement of citizens and creation of a local network |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gatti, F.; Procentese, F. Local Community Experience as an Anchor Sustaining Reorientation Processes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084385

Gatti F, Procentese F. Local Community Experience as an Anchor Sustaining Reorientation Processes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084385

Chicago/Turabian StyleGatti, Flora, and Fortuna Procentese. 2021. "Local Community Experience as an Anchor Sustaining Reorientation Processes during COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084385

APA StyleGatti, F., & Procentese, F. (2021). Local Community Experience as an Anchor Sustaining Reorientation Processes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 13(8), 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084385