Influence of Vision on Educational Performance: A Multivariate Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Monocular Visual Acuity (distanced vision),

- -

- Fogging test with +2.00 D to exclude hyperopia of ≥+2.00 D [18],

- -

- Shober phoria test to evaluate binocular vision,

- -

- Binocular Visual Acuity (near vision),

- -

- Near Point of Convergence (NPC),

- -

- Ocular motility.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Global Education Monitoring Report (GEM) by UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261016 (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Knopf, J.A.; Finnie, R.K.; Peng, Y.; Hahn, R.A.; Truman, B.I.; Vernon-Smiley, M.; John-son, V.C.; Johnson, R.L.; Fielding, J.E.; Muntaner, C.; et al. School-based health centers to advance health equity: A community guide systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Vision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.S.; Park, S.C.; Park, C.M. Relationship between accommodative and vergence dysfunctions and academic achievement for primary school children. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2009, 29, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, C.C.; Paiva, A.P.G.; Camilo, G.B.; Maior, M.R.S.; Leite, I.C.G.; Guerra, M.R. Early detection of visual mpairment and its relation with school effectiveness. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2010, 56, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; Alvarez-Peregrina, C.; Villa-Collar, C.; Sánchez-Tena, M. Ángel Current State and Future Trends: A Citation Network Analysis of the Academic Performance Field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, S.; Vincent, S.J.; Sampson, G.P.; Wood, J.M. Visual demands in modern Australian primary school classrooms. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2016, 99, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomo-Álvarez, C.; Puell, M.C. Accommodative function in school children with reading difficulties. Graefe Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 246, 1769–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, H.D.; Grisham, J.D. Binocular anomalies and reading problems. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1987, 58, 578–587. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, L.W.; Nandakumar, K.; Hrynchak, P.K.; Irving, E.L. Visual and binocular status in elementary school children with a reading problem. J. Optom. 2018, 11, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo PrevInfad/PAPPS Infancia y Adolescencia. Guía de Actividades Preventivas por Grupos de edad. En Recomendaciones PrevInfad/PAPPS [en línea]. Actualizado mayo de 2014. Available online: http://previnfad.aepap.org/recomendacion/actividades-por-edad-rec (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Abu, B.; Nurul, F.; Hong, C.; Goh, P. COVD-QOL question-naire: An adaptation for school vision screening using Rasch analysis. J. Optom. 2012, 5, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, T.F.; Sheetz, A.; Gurm, R.; Woodward, A.C.; Kline-Rogers, E.; Leibowitz, R.; DuRussel-Weston, J.; Palma-Davis, L.; Aaronson, S.; Fitzgerald, C.M.; et al. Understanding childhood obesity in America: Linkages between household income, community resources, and children’s behaviors. Am. Hear J. 2012, 163, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, A.S.; Young, D.E.; He, X.; Chen, T.C.; Wagenaar, R.C.; Stern, C.E.; Schon, K. Research report: Interaction between serum BDNF and aerobic fitness predicts recognition memory in healthy young adults. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 259, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Dinges, D.F. A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remígio, M.C.; Leal, D.; Barros, E.; Travassos, S.; Ventura, L.O. Achados oftalmológicos em pacientes com múltiplas deficiências. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2006, 69, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leandro, J.E.; Meira, J.; Ferreira, C.S.; Santos-Silva, R.; Freitas-Costa, P.; Magalhães, A.; Breda, J.; Falcão-Reis, F. Adequacy of the Fogging Test in the Detection of Clinically Significant Hyperopia in School-Aged Children. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 3267151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Ping, S. Post-1990s College Students Academic Sustainability: The Role of Negative Emotions, Achievement Goals, and Self-efficacy on Academic Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Chen, A.H.; Bleything, W.; Lim, Y.Y. Relating visión status to academic achievement among year-2 school children in Malaysia. Optometry 2011, 82, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholtz, I. Results from a pediatric vision screening and its ability to predict academic performance. Optometry 2000, 71, 426–430. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, H.D.; Grisham, J.D. Vision and reading disability: Research problems. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1986, 57, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotingo, E.I.; Obodo, D.U.; Iroka, F.T.; Ebeigbe, E.; Amakiri, T. Effects of Reduced visual Acuity on Academic performance among secondary school students in south-south Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 2319–7064. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg, H.K.; Langaas, T.; Svarverud, E. Vision status of children aged 7–15 years referred from school vision screening in Norway during 2003–2013: A retrospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Peregrina, C.; Sánchez-Tena, M.Á.; Martinez-Perez, C.; Villa-Collar, C. The Relationship Between Screen and Outdoor Time with Rates of Myopia in Spanish Children. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 560378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstand, S.; Koslowe, K.C.; Parush, S. Vision, Visual-Information Processing, and Academic Performance among Seventh-Grade Schoolchildren: A More Significant Relationship Than We Thought? Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, S.; Black, A.A.; White, S.L.J.; Wood, J.M. Visual information processing skills are associated with academic performance in Grade 2 school children. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, e1141–e1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirani, M.; Zhang, X.; Goh, L.K.; Young, T.L.; Lee, P.; Saw, S.M. The Role of Vision in Academic School Performance. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010, 17, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morad, Y.; Lederman, R.; Avni, I.; Atzmon, D.; Azoulay, E.; Segal, O. Correlation between reading skills and different measurements of convergence amplitude. Curr. Eye Res. 2002, 25, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulp, M.T. Relationship between visual motor integration skill and academic perfomance in kindergarten through third grade. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1999, 76, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusek, W.; Pierscionek, B.K.; McClelland, J.F. A survey of visual function in an Austrian population of school-age children with reading and writing difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, S.; Narayanasamy, S.; Vincent, S.J.; Sampson, G.P.; Wood, J.M. Do reduced visual acuity and refractive error affect classroom performance? Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020, 103, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A.; Zaba, J.N. The visual screening of adjudicated adolescents. J. Behav. Opt. 1999, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon, S.K.; Stewart-Brown, S.L. Preschool vision screening. Health Technol. Assess. 1997, 1, i–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashedd, S.H.; Elamdina, A.M. Effect of Binocular Vision Problems on Childhood Academic Performance and Teachers’ Perspectives. Pak. J. Ophtalmol. 2020, 36, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiman, M.; Chase, C.; Borsting, E.; Lynn Mitchell, G.; Kulp, M.T.; Cotter, S.A.; CITT-RS Study Group. Effect of treatment of symptomatic convergence insufficiency on reading in children: A pilot study. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2018, 101, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.M.; Black, A.; Hopkins, S.; White, S.L.J. Vision and academic performance in primary school children. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2018, 38, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero Ferrera, J.M.; Simancas Rodríguez, R. Investigaciones de Economía de la Educación, 1st ed.; Asociación de Economía de la Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

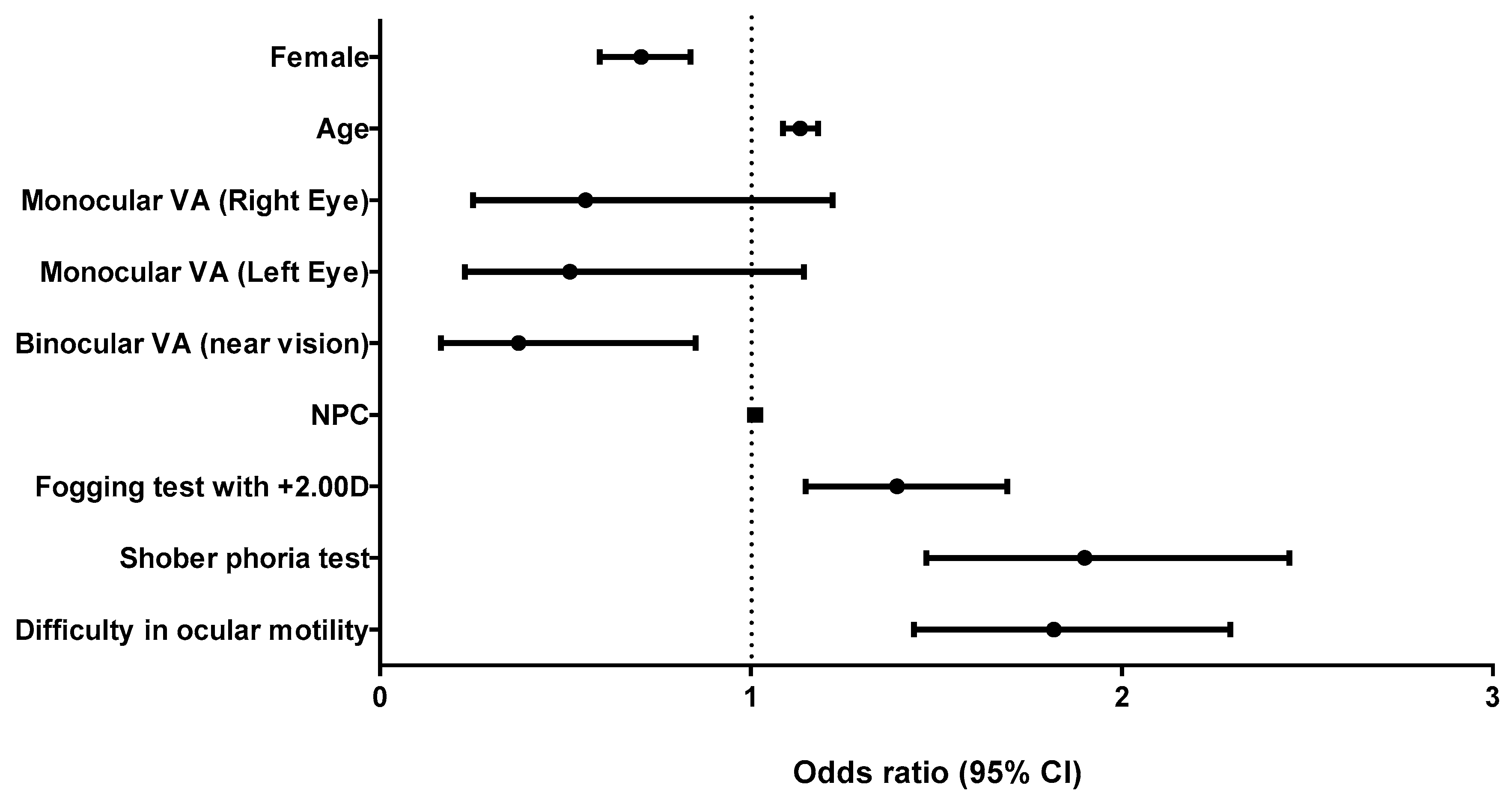

| Poor Academic Performance | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | z | p > z | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.704 | 0.062 | −3.980 | <0.001 | 0.593 | 0.837 |

| Age | 1.133 | 0.025 | 5.770 | <0.001 | 1.086 | 1.182 |

| Monocular VA (Right Eye) | 0.554 | 0.223 | −1.470 | 0.142 | 0.251 | 1.220 |

| Monocular VA (Left Eye) | 0.512 | 0.210 | −1.630 | 0.102 | 0.229 | 1.143 |

| Binocular VA (near vision) | 0.374 | 0.157 | −2.350 | 0.019 | 0.164 | 0.851 |

| NPC | 1.011 | 0.007 | 1.500 | 0.133 | 0.997 | 1.026 |

| Fogging test with +2.00 D | 1.394 | 0.138 | 3.360 | 0.001 | 1.148 | 1.692 |

| Shober phoria test | 1.900 | 0.247 | 4.940 | <0.001 | 1.473 | 2.452 |

| Dificulty in ocular motility | 1.817 | 0.215 | 5.040 | <0.001 | 1.440 | 2.292 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarez-Peregrina, C.; Villa-Collar, C.; Andreu-Vázquez, C.; Sánchez-Tena, M.Á. Influence of Vision on Educational Performance: A Multivariate Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084187

Alvarez-Peregrina C, Villa-Collar C, Andreu-Vázquez C, Sánchez-Tena MÁ. Influence of Vision on Educational Performance: A Multivariate Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084187

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez-Peregrina, Cristina, Cesar Villa-Collar, Cristina Andreu-Vázquez, and Miguel Ángel Sánchez-Tena. 2021. "Influence of Vision on Educational Performance: A Multivariate Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084187

APA StyleAlvarez-Peregrina, C., Villa-Collar, C., Andreu-Vázquez, C., & Sánchez-Tena, M. Á. (2021). Influence of Vision on Educational Performance: A Multivariate Analysis. Sustainability, 13(8), 4187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084187