Urban Creative Sustainability: The Case of Lublin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Empirical Contribution

2.2. The Design/Methodology Approach

2.3. Research Limitations/Implications

2.4. Originality/Value

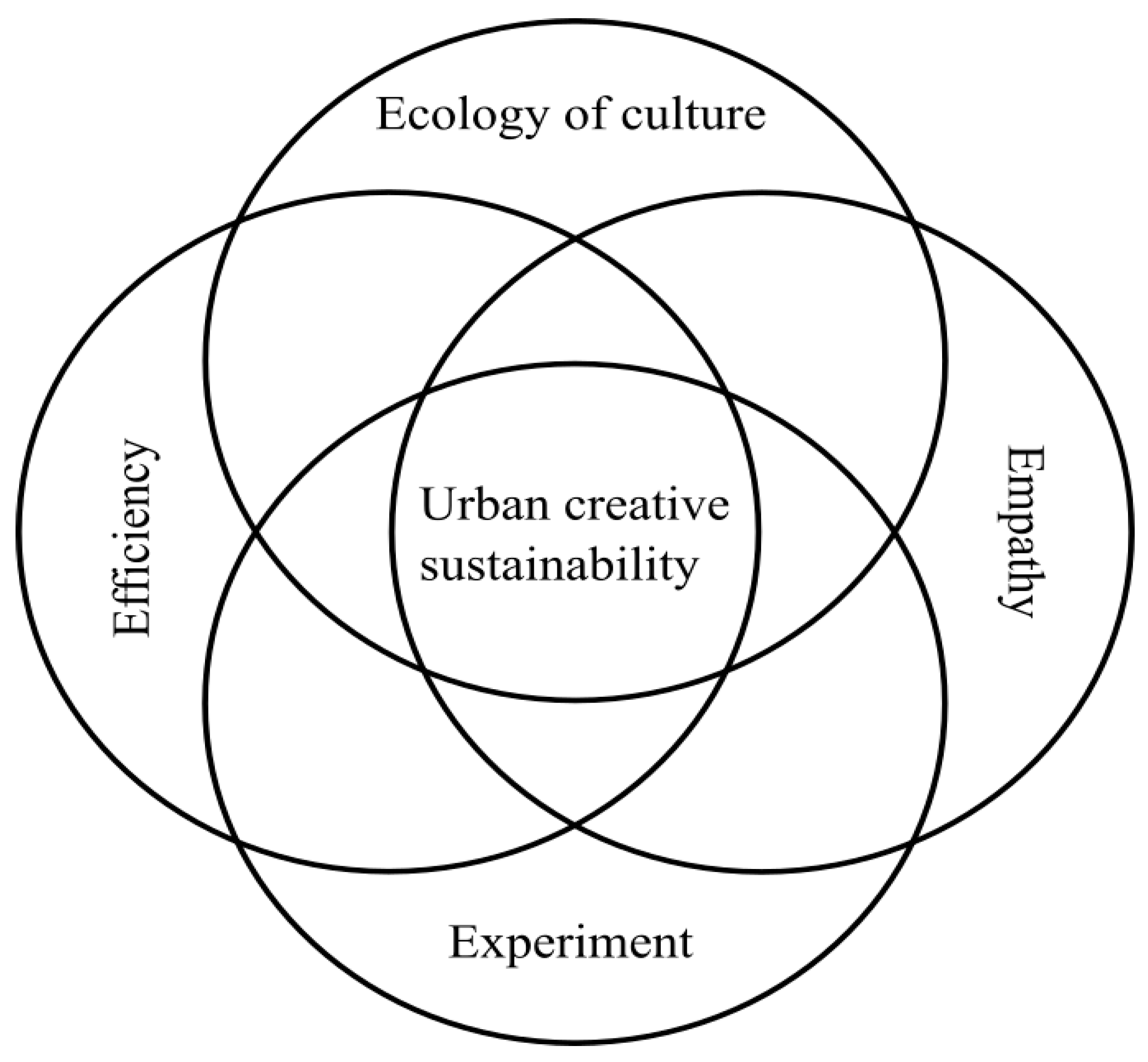

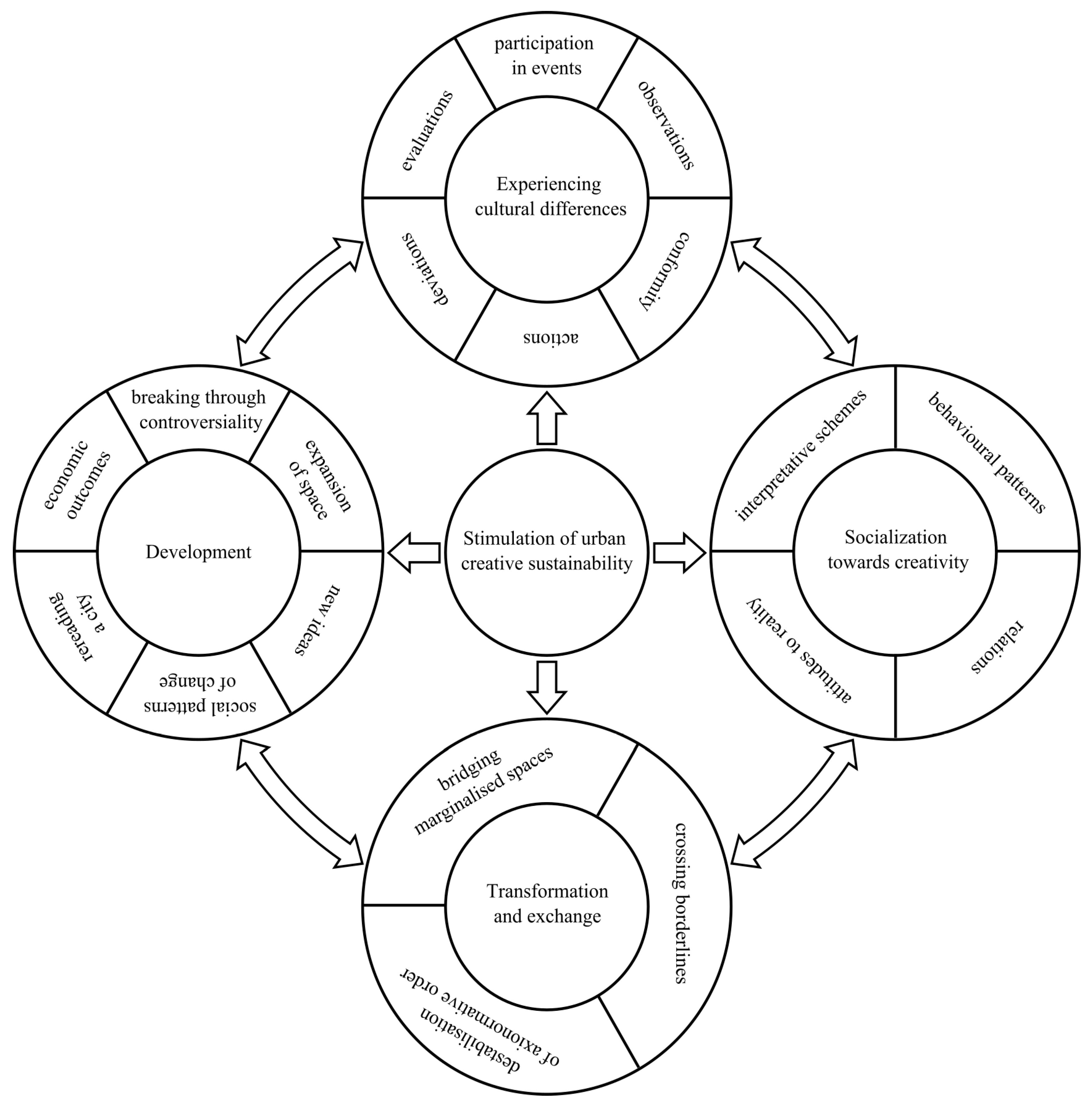

3. Creative Urban Sustainability Transition

3.1. From Deviation to Creativity

3.2. Experiencing the Creativity of Spaces

“Yes, definitely yes. In any space you can express something, communicate to others, for example, some information. Anyone who is in a public space can perform the role of an audience.”

“Creative spaces are areas where various festivals, meetings, cultural events are organised. The Old Town, for example, is such a place.”

“Positive. Spaces of creativity are expanding their boundaries. They are moving away from the city centre, from the Old Town and into the districts.”

“Creative spaces are increasingly local. The immediate vicinity of the place of residence is a very good area for stimulating creative activity, supporting multicultural identity and educating one about the need for intercultural dialogue.”

“The trend is to bring this urban creativity closer to the citizen. Earlier, it had to be reached, one needed to get to this ‘centre of events’.”

“Creative spaces become active seasonally, not on a permanent basis […].”

“New technologies are new tools of creativity or a source of information about creativity, creative activity, and organised events. New technologies expand what we have in real life and create a new quality. They help to widen access to creativity, e.g., for people with disabilities.”

“Yes, young people and seniors are the most creative. There are many activities aimed at seniors in Lublin. I understand creativity as innovation. People between the ages of 40–50 are mostly excluded from these activities. Maybe even 35-year-olds.”

“Yes, young people are more inclined to use new technologies. New technologies are natural for them. Senior citizens need to put more work, more effort into using new technologies, and the effects of learning, acquiring these competences are smaller.”

“No. In order for them to be able to see it for themselves, they must be properly prepared for multiculturalism, for understanding it, experiencing it and being open to it. There are many approaches and attitudes to multiculturalism. Education should be conducive to learning to read what we encounter in urban space.”

“They are already familiar with it. Many such undertakings have already taken place. It is becoming increasingly difficult to attract attention in order to be controversial. Organised cultural events make people get used to multiculturalism […]. Multiculturalism and such controversiality are already canons of culture in Lublin, in a positive sense, of course.”

“Lublin is a city of inspiration.”

“It is, but it seems to me that it is expanding and merging. It just started with culture, but now when we are talking about a creative city, it is about something else. Lublin has transferred creativity to the economy, to the economic brand, especially to IT companies. It is all about creativity and knowledge. They started with culture, and it has all moved elsewhere, to social innovation.”

4. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earth Scan Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Yin, C.; Xia, W. Sustainable urban environment in the context of globalization: “Cambridge future” science and technology park. Open House Int. 2017, 42, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galazova, S.S. Creative industries: Problems of market transformation. Terra Econ. 2016, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caves, R. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Global sustainability and the creative destruction of industries. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1999, 41, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, F. Community and Society; Loomis, C.P., Ed.; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rompay, T.J.L.; van Tineke, J. Wild and free: Unpredictability and spaciousness as predictors of creative performance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.Y.C.; Fischer, R.; McClure, J. Are nature lovers more innovative? The relationship between connectedness with nature and cognitive styles. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, L.; Chapain, C. The integration of cultural and creative industries into local and regional development strategies in Birmingham and Marseille: Towards an inclusive and collaborative governance? Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarick, K.; Smirnova, O. Are creative and green cities also smart and sustainable? Smart cities as democratic ecologies. In Smart Cities as Democratic Ecologies; Araya, D., Ed.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 87–115. [Google Scholar]

- Mohareb, N.; Elsamahy, E.; Felix, M. A Child-friendly city: A youth creative vision of reclaiming interstitial spaces in El Mina (Tripoli, Lebanon). Creat. Stud. 2019, 12, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.; Neij, L.; Mont, O.; Ryan, C.; Rodhe, H.; Orsato, R. Advancing sustainable solutions: An interdisciplinary and collaborative research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Rueda, R.A. Use of the flipped classroom to design creative and active activities in the field of computer science. Creat. Stud. 2020, 13, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salı, G. Examining the development of creativity in adolescents in 9th and 12th grades: A four-year longitudinal study. Creat. Stud. 2019, 12, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, S.; Misoczky, M.C.; Moog, S. Greening capitalism? A Marxist critique of carbon markets. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1617–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; De Propris, L. A policy agenda for EU smart growth: The role of creative and cultural industries. Policy Stud. 2011, 32, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, W.G. Responding to the undesired. State responsibility, risk management and precaution. Neth. Yearb. Int. Law 2005, 36, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jonas, H. The imperative of responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age; Jonas, H., Herr, D., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Polity Press and Blackwell Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk society: Towards a new modernity. In Theory, Culture and Society; Ritter, M., Ed.; Sage: London, UK; Riverside County, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cucuzzella, C. Creativity, sustainable design and risk management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, D. Global creative economy and Istanbul: A focus on film industry cluster. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.; Lawrence, L.N. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Hofverberg, H.; Kronlid, D.O.; Östman, L. Crafting sustainability? An explorative study of craft in three countercultures as a learning path for the future. Nord. J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2017, 5, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burns, T.R.; Machado, N.; Corte, U. The Sociology of Creativity: Part I: Theory: The Social Mechanisms of Innovation and Creative Developments in Selectivity Environments. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2015, 34, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpin, T.; Whitttington, J.L.; Bell, G. Is your sustainability strategy sustainable? Creating a culture of sustainability. Corp. Gov. 2015, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, A.; Ivaldi, E.; González-Relaño, R.A. Partially Non-Compensatory Method to Measure the Smart and Sustainable Level of Italian Municipalities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiaździński, E.; Kaczorowska-Spychalska, D.; Moreira Pinto, L. Is it a smart city a creative place? Creat. Stud. 2020, 13, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N.; Tjahjadi, B. Eco-oriented culture and financial performance: Roles of innovation strategy and eco-oriented continuous improvement in manufacturing state-owned enterprises, Indonesia. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaižutytė-Filipavičienė, Ž. Jewish heritage in the creative cities of Central and Eastern Europe: Tourism, technologies and prosthetic memory. Creat. Stud. 2020, 13, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Hosagrahar, J.; Sailer, A.F. Why development needs culture. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirski, R.; Gut, A. Action-based versus cognitivist perspectives on socio-cognitive development: Culture, language and social experience within the two paradigms. Synthese 2020, 197, 5511–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, W.H.; Reisdorf, B.C. Cultural divides and digital inequalities: Attitudes shaping Internet and social media divides. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotorova, E.G. Describing cross-cultural speech behavior: A communicative pragmatic field approach. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 154, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, A. Multicultural society. Res. J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 6, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, T. The Idea of Culture; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, S.; Luque-Ayala, A.; McFarlane, C. Smart Urbanism. Utopian Vision or False Dawn? Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiulis, N. Communicative creativity: From customary metaphysics to original ontology. Creat. Stud. 2018, 11, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, D. Audiovisuality and the city of Marseille, France: Creativity, communication, representation. Creat. Stud. 2019, 12, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miczka, T. Audiovisuality of the Third Degree: Reality or Fantasy. In Technology, Society and Sustainability; Zacher, L., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W. Diagramming a Theory of Change. Learn. Sustain. 2016. Available online: https://learningforsustainability.net/post/diagramming-theory-change/ (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Xiaoling, Z.; Huan, L. Urban resilience and urban sustainability: What we know and what do not know? Cities 2018, 72 Pt A, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk, M.; Betlej, A.; Gondek, J.; Ohotina, A. Technology and sustainable development: Towards the future? Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 2003–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, L.W. Are We Overcivilized? Toward (a) More Sustainable Future(s). In Spirituality and Civilization Sustainability in the 21st Century; Targowski, A., Celinski, M.J., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gondek, N. Methodological Foundations of the Language of Metaphysics. Filosofija. Sociol. 2020, 31, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.W.; Gaskell, G. Individual and group interviewing. In Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook for Social Research; Bauer, M.W., Gaskell, G., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2000; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bruper, J. Life as narrative. Soc. Res. 2004, 71, 691–711. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. Data are everywhere: Narrative criticism in the literature of experience. In Narrative Analysis: Studying the Development of Individuals in Society; Daiute, C., Lighfoot, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; Brennan-Horley, C.; Laurenson, B.; Riggs, B.; Warren, A.; Gallan, B.; Brown, H. Cool places, creative places? Community perceptions of cultural vitality in the suburbs. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2012, 15, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Baeza, J.; Bley, J.; Hartkopf, K.; Niggemann, M.; Arias, J.; Wiedenhöfer, A. Evaluating Cultural Impact in Discursive Space through Digital Footprints. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokół, A.; Słupińska, K. Creative management of the advertising form and content. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 842–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foth, M.; Satchell, C.; Brereton, M.; Choi, H.J. Internet Technology and Urban Sustainability. In Proceedings of the IR 9.0: Rethinking Communities, Rethinking Place—Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR) Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gondek, J. New technologies in sustainable urban development. Transformacje = Transformations 2019, 3–4, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jász, B. Mental map of the city: Elements of visual argumentation and creativity in modern city planning. Creat. Stud. 2018, 11, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miczka, T. The state of anthropological uncertainty as an educational problem. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2018, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miczka, T. Specifics of Algorithmization in Data Culture. Eur. J. Eng. Form. Sci. 2019, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, J.; Istenič, S.P.; Komac, B. Green creative environments: Contribution to sustainable urban and regional development. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdoff, F.; Foster, J.B. What every environmentalist needs to know about capitalism. Mon. Rev.-Indep. Social. Mag. 2010, 61, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Betlej, A.; Kačerauskas, T. Urban Creative Sustainability: The Case of Lublin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074072

Betlej A, Kačerauskas T. Urban Creative Sustainability: The Case of Lublin. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074072

Chicago/Turabian StyleBetlej, Alina, and Tomas Kačerauskas. 2021. "Urban Creative Sustainability: The Case of Lublin" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074072

APA StyleBetlej, A., & Kačerauskas, T. (2021). Urban Creative Sustainability: The Case of Lublin. Sustainability, 13(7), 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074072