Modifying Tradition: Understanding Organizational Change in Chinese Elite Sport Training at the Grassroots Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the impetuses for changing from an old template to a new template?

- (2)

- What are the factors that moderate the change process?

2. Elite Sport Training in China and an Integrative Model of Organizational Change in Sport

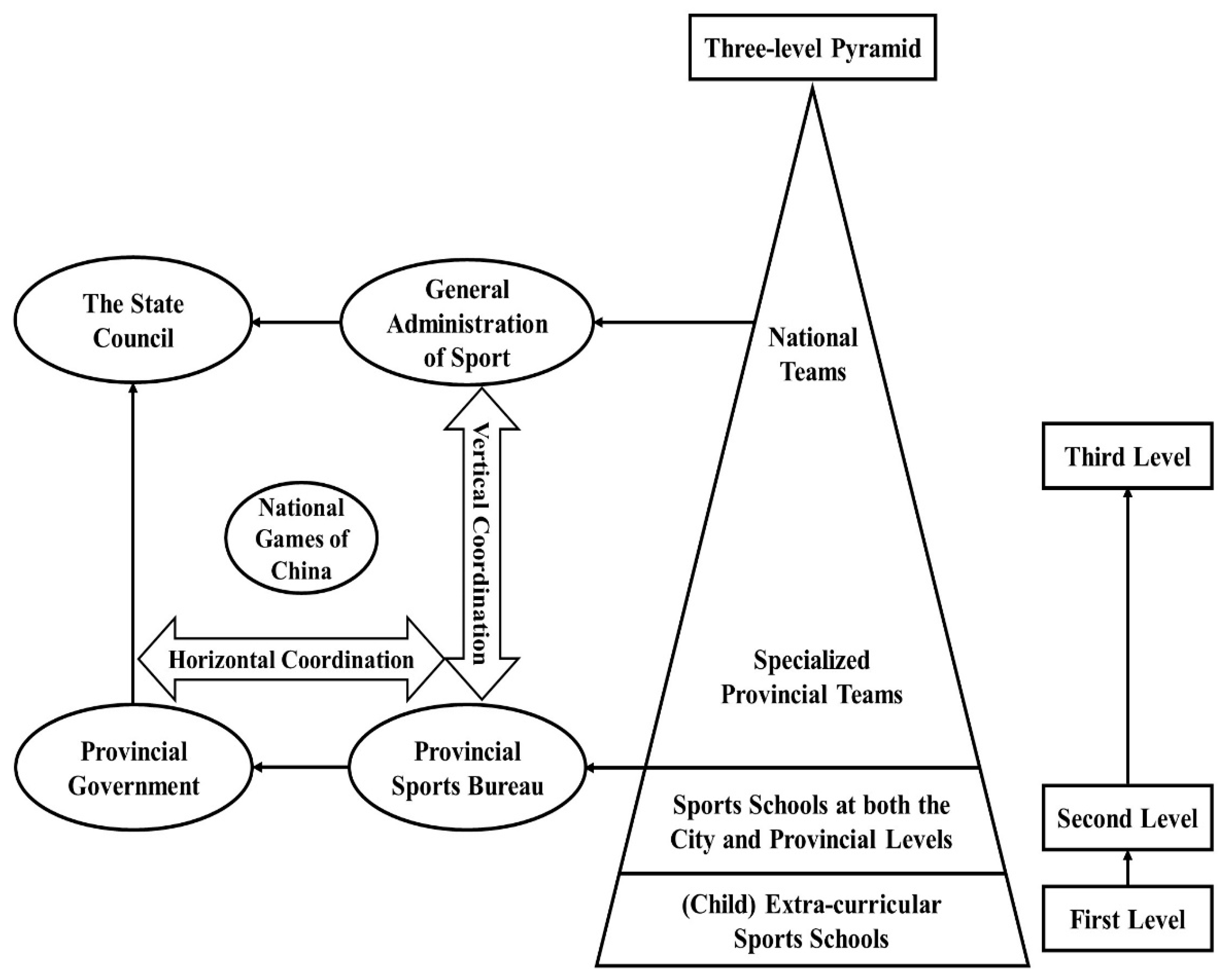

2.1. Institutional Analyses on Chinese Elite Sport Training

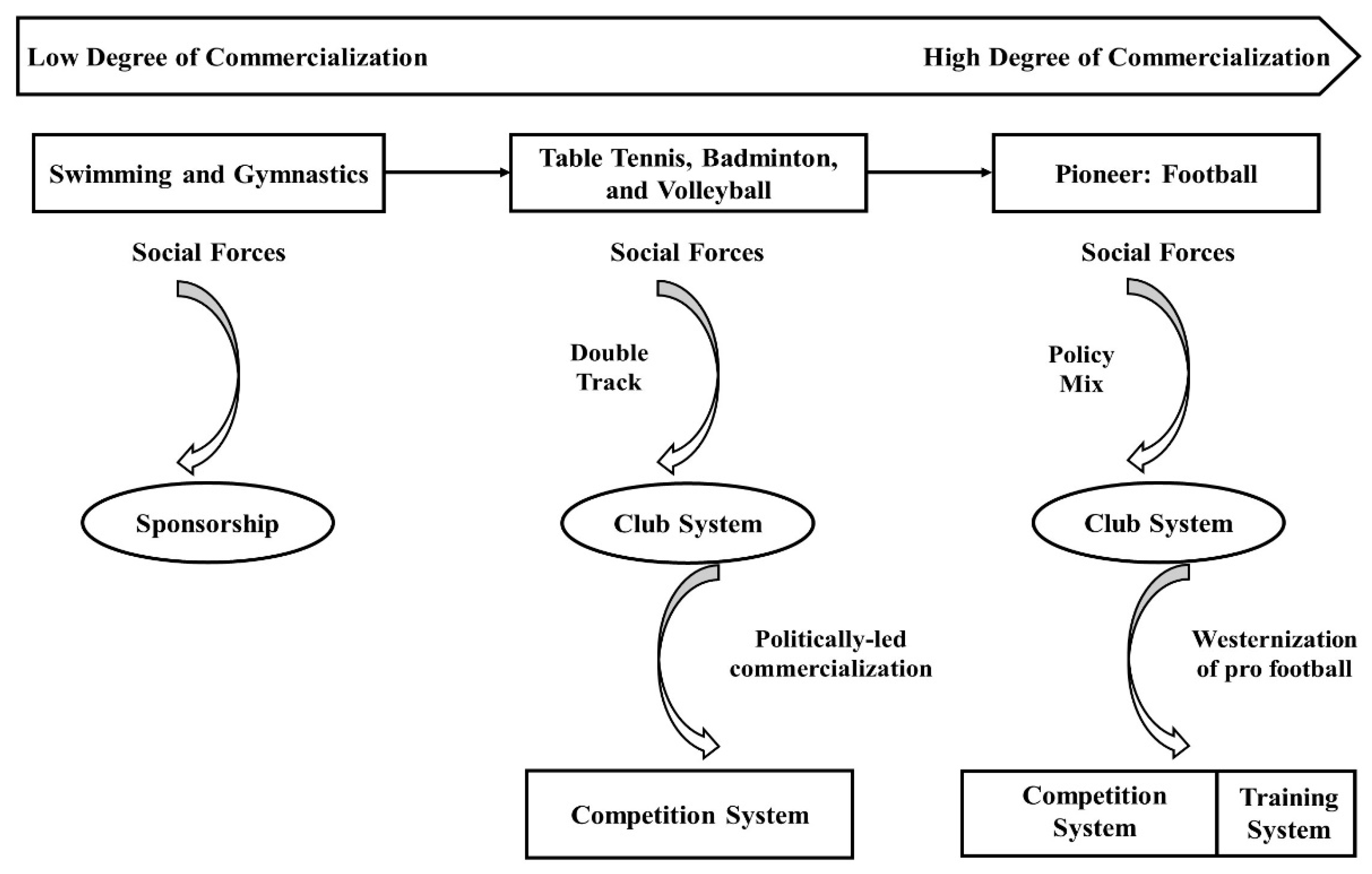

2.2. Chinese Elite Sport Training, Social Forces, and Commercialization

2.3. Theoretical Framework: An Integrative Model of Organizational Change in Sport

2.3.1. Political, Functional, and Social Pressures

2.3.2. Moderating Factors

2.3.3. Value Commitments

2.3.4. Late-Stage Moderating Factors

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design

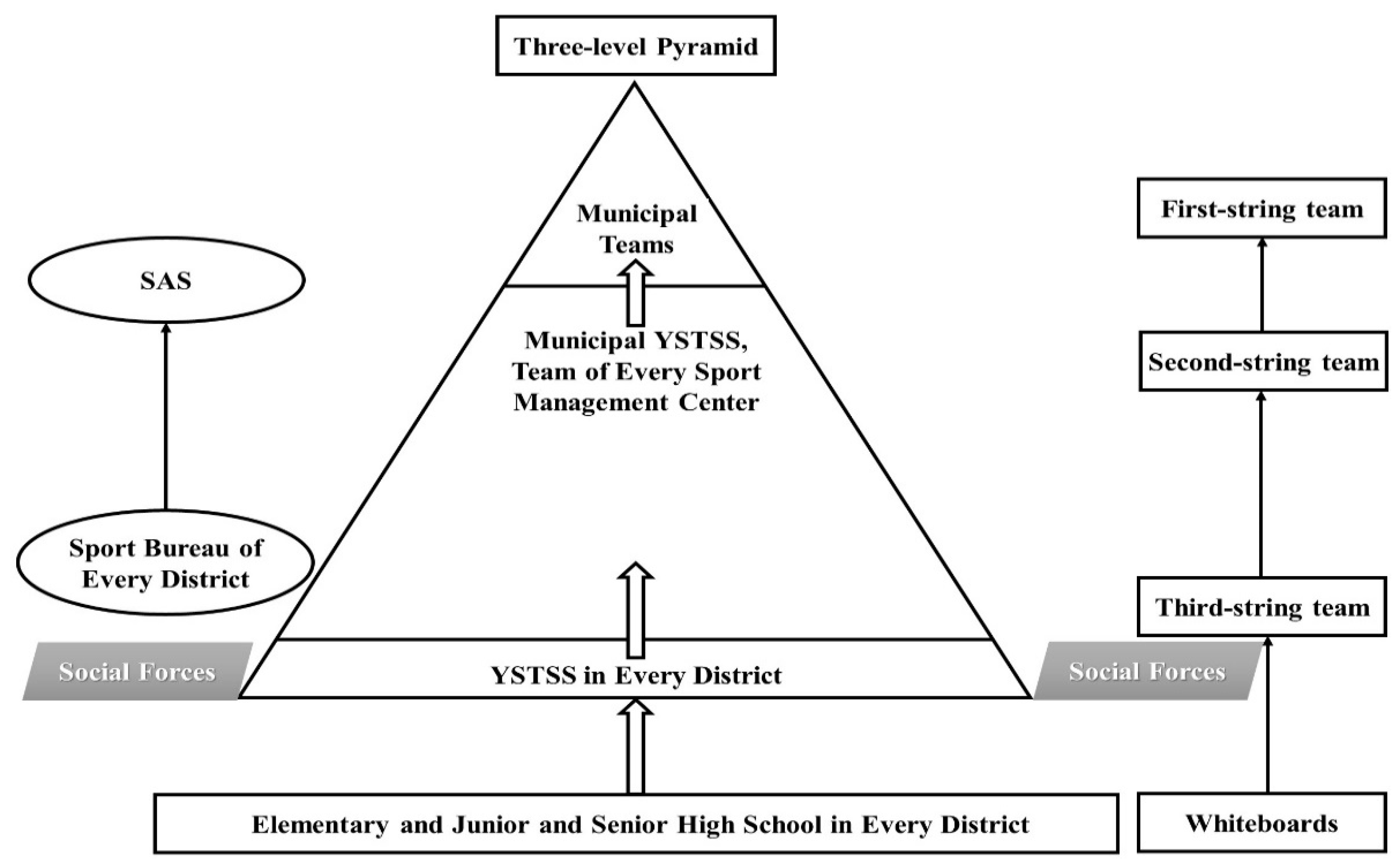

3.2. Case Context: The YSTSS in Yangpu District

3.3. Participants and Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

4. Findings

4.1. Internal and External Political Pressures

“Before the involvement of the social forces, our athletes admitted a lack of motivation and a feeling of sloth. Negatively influenced by the One-Child Policy, they, including the students from outside provinces, were largely spoiled by their parents and grandparents. The majority of the time, I had to make a phone call to their parents, kind of pleading with them again and again to bring their children here for three hours of training after school. I have no choice since my monthly salary and annual bonus are closely related to the performance of the athletes that I train. By convention, an internal selection is held to choose the athletes who are eligible to participate in the municipal competition on behalf of the Yangpu YSTSS. As far as I am concerned, this internal selection is meaningless”.(Interviewee E).

“In seeking to cope with the acute structural imbalance between sporting goods manufacturing and the sport service sector, policy No. 46 (Promotion Guidelines) encourages the numerous social forces to set up and run sport clubs. We insist that there is no conflict between developing the sport service industry and elite sport training. These two are not mutually exclusive. Instead, we uphold that, broadly, elite sport training and the sport service industry could be well aligned. We require the YSYSS in every district to allow the registration of social sport clubs. If social sport clubs identify young hopefuls during their daily operation, they can provide them to the YSYSS in the corresponding district and further broaden the talent pool, which is vital for the construction of sport power”.(Interviewee J).

“Compared to the old times, we are carrying much more burdens on our heads. Currently, the actual expenditures on catering for the athletes are almost 10 times greater than before. The travelling costs are even approximately 50 times. This does not mean we are prepared to cut down the financial investment in elite sport training. This situation will definitely not happen in the foreseeable future. What we really need is to make full use of the social forces”.(Interviewee B).

4.2. Functional and Social Pressures

“The YSTSS in Yangpu district has constantly suffered from a reserve shortage of equestrian and golf talents. However, one fact that cannot be ignored is that an increasing number of equestrian and golf clubs operated by social forces have emerged in Shanghai. The only technically feasible way for the Yangpu YSTSS to address this functional defect is to absorb the young hopefuls who were trained at the equestrian and golf clubs run by social forces. In contrast, social forces are always eager to be recognized as “legitimized” members of the YSTSS capable of participating in municipal competitions on behalf of the YSTSS. If they are strong enough, the gold medals they earn will bring them a good training reputation”.(Interviewee A).

“For example, the rock climbing, the YSTSS in Yangpu district deliberately proposed a strategy that encourages wrestling athletes to train in rock climbing in the meantime. However, the effectiveness of this countermeasure is always in doubt. Our organizational goal is to provide young talent to the upper level. Indeed, we are faced with pressure to broaden the talent pool of newly added Olympic sports/disciplines”.(Interviewee F).

“Sometimes, we feel embarrassed when encountering the discussion of whether China is a major sports country or a world sports power. It is evident that the public is currently highly concerned about the quality of gold medals. For example, the public is very satisfied with the performance of women’s volleyball. Indeed, what we can do is try to extend the talent pool of internationally influential sports/disciplines as far as we can. Under these circumstances, the numerous sport clubs run by social forces are warmly welcomed to register with the Yangpu YSTSS”.(Interviewee D).

4.3. Moderating Factors Aiding the Change

“Within the Chinese economic landscape and in the setting of economic prosperity, the involvement of social forces did not jeopardize our economic growth and instead was perceived as an effective approach to ensure political stability for preventing massive unemployment and labor unrest. Returning to the elite sport training domain, we are confident that the involvement of social forces in grassroots sport training is trouble-free”.(Interviewee I).

“To be honest, for our Yangpu YSTSS, sometimes we are nervous that we cannot recruit the strongest social sport club. You may think if the social sports clubs are located in Yangpu district, they must register with our Yangpu YSTSS. No, you are wrong! There is no limit; they could complete the registration procedure in the Changning, Minhang, Jiading districts as they like”.(Interviewee D).

“We are absolutely eager to complete the registration procedure in the YSTSS in Yangpu district. This practice signals that we are eventually recognized by the governmental agency and we are part of their plan, their blueprint for the future of elite sport training. The direct benefit of registration for us is that we could obtain opportunities to compete on behalf of the Yangpu YSTSS. If we are lucky enough, one gold medal earned by an athlete who was trained in our club is the best advertisement”.(Interviewee K).

“It is understandable that parents always try to find a reliable training organization for their kids. Undoubtedly, a gold medal strongly signals that we are reliable and effective, and we can provide the best training as the gold medal winner received it before. Anyway, we are eager to help the Yangpu YSYSS make the change”.(Interviewee M).

4.4. Reformative Commitment and the Late-Stage Moderating Factor

“Compared to the sport clubs run by social forces, we do have a competitive advantage; for instance, we are free of charge and even offer lunch and dinner, which are also free. By contrast, the sport clubs outside are profit-driven. They always in pursuit of profits and charge the parents a lot annually”.(Interviewee G).

“For most parents, the greatest concern is about potential sporting injuries. Here, in the Yangpu YSTSS, we can provide the most experienced doctor who guarantees the best treatment of athletes if any injuries occur”.(Interviewee D).

“It is relatively easy for us to implement the transition. The registration procedure costs nothing. It is always convenient to invite the best athletes from social sport clubs to participate in our internal selection”.(Interviewee D).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawler, E., III; Mohrman, A.M., Jr.; Mohrman, S.A.; Ledford, G., Jr.; Cummings, T.G. Doing Research That Is Useful for Theory and Practice; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Peachey, J.W.; Bruening, J. Investigating ambivalence towards organisational change in a football championship subdivision intercollegiate athletic department. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Organizations: A Quantum View; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, K.L.; Stanley, D.N. Managing Radical Organizational Change; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, S. Exploring China’s success at the Olympic Games: A competitive advantage approach. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 148–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, S.; Tan, T.C.; Houlihan, B. Sport Policy in China; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter, A.M.; Kilvinger, B.; Bodemar, A.; Skille, E.Å.; Kurscheidt, M. Dual governance structures in action sports: Institutionalization processes of professional snowboarding revisited. Sport Soc. 2018, 22, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.R. Ideological conflicts behind mutual belief: The termination of the ‘dual-registration policy’ and the collapse of an effective elite diving system in China. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1362–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.-C.; Houlihan, B. Chinese Olympic sport policy: Managing the impact of globalisation. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2012, 48, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wu, P.; Xiong, H. Beijing ambitions: An analysis of the Chinese elite sports system and its Olympic strategy for the 2008 Olympic Games. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2005, 22, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Lau, P.W.C.; Chen, S.; Dickson, G.; De Bosscher, V.; Peng, Q. Interorganisational conflict between national and provincial sport organisations within China’s elite sport system: Perspectives from national organisations. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhuanet. Shanghai Facilitates the Involvement of Social Forces into Elite Sport Training Establish the Social Forces Training Center for Elite Sport Backups. Available online: http://sports.xinhuanet.com/c/2020-09/28/c_1126554905.htm (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Xinmin. Shanghai Social Forces’ Engagement in Elite Sport Training Steps into a New Period. Available online: https://paper.xinmin.cn/html/dfsports/2020-09-30/A08-A09/22577.html (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ma, Y.; Kurscheidt, M. Governance of the Chinese super league: A struggle between governmental control and market orientation. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 9, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Signaling soft power through medal success: China as an example. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 1827–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kurscheidt, M. The national games of China as a governance instrument in Chinese elite sport: An institutional and agency analysis. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2019, 11, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chin, J.W.; Reekie, S.H.M. Education in the Chinese national sport system: Experiences of professional wushu athletes. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1466–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. Innocence lost: Child athletes in China. Sport Soc. 2004, 7, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Developing a sustainable football model with the AFC vision Asia philosophy-two grassroots development cases in Zibo and Qingdao. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.-C.; Bairner, A. Globalization and Chinese sport policy: The case of elite football in the people’s Republic of China. China Q. 2010, 203, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kurscheidt, M. Doing it the Chinese way: The politically-led commercialization of professional football in China. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2020, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, S.; Jiang, I.G.T. China: Emerging football nation, emerging governance issues. In Research Handbook on Sport Governance; Winand, M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, J.J.; Desbordes, M. Sport business in China: Current state and prospect. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2017, 18, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.; Chadwick, S.; Gow, M. China’s football dream: Sport, citizenship, symbolic power, and civic spaces. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2019, 43, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Bairner, A. Chinese football fandom and civic identities: A study of the fans of Shanghai Shenhua and Beijing Guoan. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 2078–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Watanabe, N.M.; Chen, R.; Newman, J.I.; Yan, G. Football (as) Guanxi: A relational analysis of actor reciprocity, state capitalism, and the Chinese football industry. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 2005–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurscheidt, M.; Deitersen-Wieber, A. Sport governance in Germany. In Sports Governance in the World: A Socio-Historic Approach; Sobry, C., Ed.; Editions Le Manuscrit: Paris, Franch, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Amis, J.; Slack, T.; Hinings, C.R. Strategic change and the role of interests, power, and organizational capacity. J. Sport Manag. 2004, 18, 158–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, P.S. Institutional environments and resource dependence: Sources of administrative structure in institutions of higher education. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B. Understanding the diversity-related change process: A field study. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, J.; Snelgrove, R.; Wood, L. Modifying tradition: Examining organizational change in youth sport. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B. Removing the blinders: Toward an intergrative model of organizational change in sport and physical activity. Quest 2002, 54, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Hinings, C.R. Understanding radical organizational change: Bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 1022–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S. The social processes of organizational sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Yangpu Government (SYG). Great News Shanghai Youth Spare Time Sport School Has Been Titled as the First Class among National Elite Sport Training Bases. Available online: http://www.shyp.gov.cn/shypq/yqyw-wb-tpxw-tyj/20190128/318001.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Shanghai Yangpu Government (SYG). Together with the Social Forces Yangpu Sport Bureau Broaden the Training Approaches of Elite Sport. Available online: http://www.shyp.gov.cn/shypq/yqyw-wb-tyjzl-tysl-tyshh/20191120/344800.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Abingdon, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- General Administration of Sport (GAS). Social Forces’ Operation on Sport: The Operational Insight of Rock Basketball Park; GAS: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Sohu. Broadening the Traditional Training Approach, Badminton and Fencing Involve Social Forces into Yangpu Elite Sport. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/353322821_499986 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, G. An interview to Zengxiang Zhu, the president of youth spare time sport school in Yangpu district. Chin. Sport Coach. 2008, 2, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, N. Designing Social Research; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S. Rethinking ‘validity’ and ‘trustworthiness’ in qualitative inquiry: How might we judge the quality of qualitative research in sport and exercise sciences? In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 484–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People.cn. Uniting Social Forces to Run Elite Sport Training. Available online: http://sports.people.com.cn/n1/2017/1213/c412458-29703986.html (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- State Council. The Outline of Sport Power Construction; State Council: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Houlihan, B.; Zheng, J. The Olympics and elite sport policy: Where will it all end? Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. Reading European football, critiquing China: Chinese urban middle class fans as reflexive audience. Cult. Stud. 2020, 34, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sport (GAS). The Outline of the Strategic Olympic Glory Plan: 2001–2010; GAS: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Chen, S.; Zheng, J.; Dickson, G. An organizational life cycle approach to exploring the elite sport legacy of summer Olympic host nations: The cases of China (Beijing 2008) and Australia (Sydney 2000). Int. J. Hist. Sport 2018, 35, 1276–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Henry, I. Reform and maintenance of Juguo Tizhi: Governmental management discourse of Chinese elite sport. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.C.; Huang, H.C.; Bairner, A.; Chen, Y.W. Xi Jin-Ping’s world cup dreams: From a major sports country to a world sports power. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2016, 33, 1449–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J.; Carmichael, F. Why do governments invest in elite sport? A polemic. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2012, 4, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsson, N. The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions, and Actions in Organizations; Copenhagen Business School Press: Copenhagen, Danmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grix, J.; Brannagan, P.M.; Lee, D. Entering the Global Arena: Emerging States, Soft Power Strategies and Sports Mega-Events; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, B.; Green, M. The production of Olympic champions: International perspectives on elite sport development system. Eur. J. Sport Manag. 2001, 8, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

| Interviewee Identifier | Organization | Position |

|---|---|---|

| A | Shanghai University | Professor of Sport Management Studies, one of the most renowned sports researchers in mainland PRC |

| B | Shanghai Sport University | Professor of Sport Studies with expertise in elite sport training in Shanghai |

| C | Suzhou University | Professor of Sport Studies with expertise in elite sport training in the Yangtze River Delta |

| D | YSTSS in Yangpu District | Director of the training department |

| E | YSTSS in Yangpu District | A senior coach who has served the Shanghai Team for more than 10 years |

| F | YSTSS in Yangpu District | A coach who has served the YSTSS for more than 5 years (female) |

| G | YSTSS in Yangpu District | A senior coach who has served the YSTSS for more than 10 years |

| H | SAS | Head of the youth training department |

| I | Sports Bureau of Yangpu District | Deputy director responsible for Yangpu elite sport training |

| J | SAS | Deputy director responsible for elite sport training |

| K | Social sport club registered with the Yangpu YSTSS | Club owner |

| L | Social sport club registered with the Yangpu YSTSS | Club owner |

| M | Social sport club registered with the Yangpu YSTSS | Club owner |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Kurscheidt, M. Modifying Tradition: Understanding Organizational Change in Chinese Elite Sport Training at the Grassroots Level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074048

Ma Y, Kurscheidt M. Modifying Tradition: Understanding Organizational Change in Chinese Elite Sport Training at the Grassroots Level. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074048

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yang, and Markus Kurscheidt. 2021. "Modifying Tradition: Understanding Organizational Change in Chinese Elite Sport Training at the Grassroots Level" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074048

APA StyleMa, Y., & Kurscheidt, M. (2021). Modifying Tradition: Understanding Organizational Change in Chinese Elite Sport Training at the Grassroots Level. Sustainability, 13(7), 4048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074048