Abstract

Marginal settlements may be defined as inhabited areas characterized by a series of negative features, typicallyethnic segregation, social discrimination, poor living conditions and conflicts, with impact on their dwellers and neighboring communities. In Romania, informal settlements were legislated in 2019; it subsequently became mandatory for the local authorities to spatially delimit them and formulate measures to improve living conditions. However, there are still numerous issues to be solved, from the lack of basic services (health, education) to the persistent poor living conditions or serious environmental problems. The Roma communities selected for our study are no exception. They are located on the outskirts of some cities or in their historical centers (Cluj-Napoca, Sibiu, Timișoara, Baia Mare). Through content analysis, based on print and electronic media from the last 10 years (n = 150 news items), different aspects of marginal housing were illustrated. The results of the study revealed some particular aspects, namely: some of the Roma communities are relocated whilst some others are subject to environmental conflicts; funding addressing the quality of life of Roma ethnics seems to deepen the phenomenon of segregation among communities, most of the measures being limited to the creation of housing facilities.

1. Introduction

A series of spatial phenomena such as polarization, center–periphery relations, metropolitanization, gentrification and segregation can trigger wide-ranging dynamics in urban residential areas, with significant socioeconomic effects on the local communities. One of the seemingly statistically invisible areas is that of marginal housing although residents of these communities frequently appear in the public discourse, either as a target audience for public policies or due to certain individual actions, usually negatively impacting neighboring communities. Whether we refer to media, social media or public policy documents, content analysis clearly illustrates these aspects.

A large number of informal settlements in Romania are mainly found in medium and large cities [1], especially in the suburbs of the latter category. In some cases, they are a direct consequence of the local relocation policies, while in others they are conditioned by an involuntary choice of people based on the existence of a vacant space (inhabitants not considering the ownership regime when making the decision).

Romania is not the only state where these ad hoc established communities are found, mostly inhabited by Roma population, and marked by a high degree of poverty. Some states affected by this phenomenon focus on policies and measures to eradicate or reduce segregation, while others try to turn it into a tourism resource by promoting the nomadic lifestyle of these ethnic communities [2]. The objective of this study was to capture some of the functioning mechanisms of several urban marginal settlements through content analysis of several media resources. In this regard, the specific objectives of this article were to obtain answers to the following research questions:

- (1)

- Are the marginalized housing areas in Romania objectively reflected by the media?

- (2)

- What are the operating mechanisms of the marginalized areas that are most intensively debated by the media? Further, how do the communities evolve/manifest in relation to these mechanisms?

- (3)

- To what extent do the implemented public policies at the national level meet the needs of the communities inhabiting the marginalized areas?

The study consists of several sections, describing the following aspects: a. the socioeconomic features of the marginalized housing areas, with specific focus on the Romanian context; b. case study selection and methodology employed; c. the degree of functionality of the marginalized housing areas after the implementation of national public policies and as an effect of the media influence; d. conclusive remarks on the results of the study.

1.1. Marginal Urban Housing—A Particular Way of Life

As a topic that has been discussed in several research fields (sociology, economics, geography, anthropology, etc.) we can admit today that marginality can have several meanings, from a societal one, related to the social conditions of communities, to a spatial one (isolated areas in terms of accessibility) [3,4,5]. According to other researchers, marginality can be further described by adding three different meanings: (a). underdevelopment and lack of resources, (b). relationships, oppression, (c). lack of cultural integration [6].

However, the emergence of marginalized housing areas is often associated with poverty and social exclusion, which are considered effects of the lack of equality of opportunity [7]. Community level poverty is most common among Roma communities. Poor housing and health conditions, as part of residential segregation, directly result from the lack of accessibility, income and infrastructure [8,9,10,11].

Housing clusters, based on a certain homogeneity of individuals (ethnic, in this case), socially stigmatized and called ghettos, are nothing but representations of marginalization [12]. Either spatial or social segregation can substitute each other at any time, both of them being expressions of city polarization, metaphorically known as “dual city/divided city” [13,14,15]. First, we note a reconfiguration of urban space through the emergence of new urban forms (new uses for industrial platforms, street reconfiguration, new housing types). In many cases, the stigma regarding the so-called disadvantaged (vulnerable) areas increases to an even greater extent through the perception of inhabitants, and sometimes even due to the way they are presented in the media [16]. Another claimed concept is that of “shrinkage city”, which is associated with the suburbs of large metropolises that face abandonment along with the aging of homeowners [15]. On the other hand, the American suburbs are considered rural areas and are not included in metropolitan areas [17,18].

Marginalized housing, determined by social exclusion, is commonly related to the Roma community. Despite the actions made by the national public authorities, this is the result of the inadequate implementation of social inclusion projects, in many cases, lacking collaboration between the decision makers and beneficiaries, in this case, the Roma community. The loss of self-confidence and motivation, the degradation of the positive image of this community are just some of the aspects that have had a major impact on the quality of the Roma housing [19]. Then again, another expression of marginalized housing appears as an effect of economic globalization and industrial decline that have led to the loss of the ability of the working class to act as a mobilizing factor [20]. Today, numerous former industrial neighborhoods are easily identifiable in the urban morphology as areas of spatial segregation or as “social housing neighborhoods” [12,21].

Europe 2020 strategy proposes new development policies, less developed regions being among the targeted areas [22], the priority being the eradication of poverty and social exclusion [9].

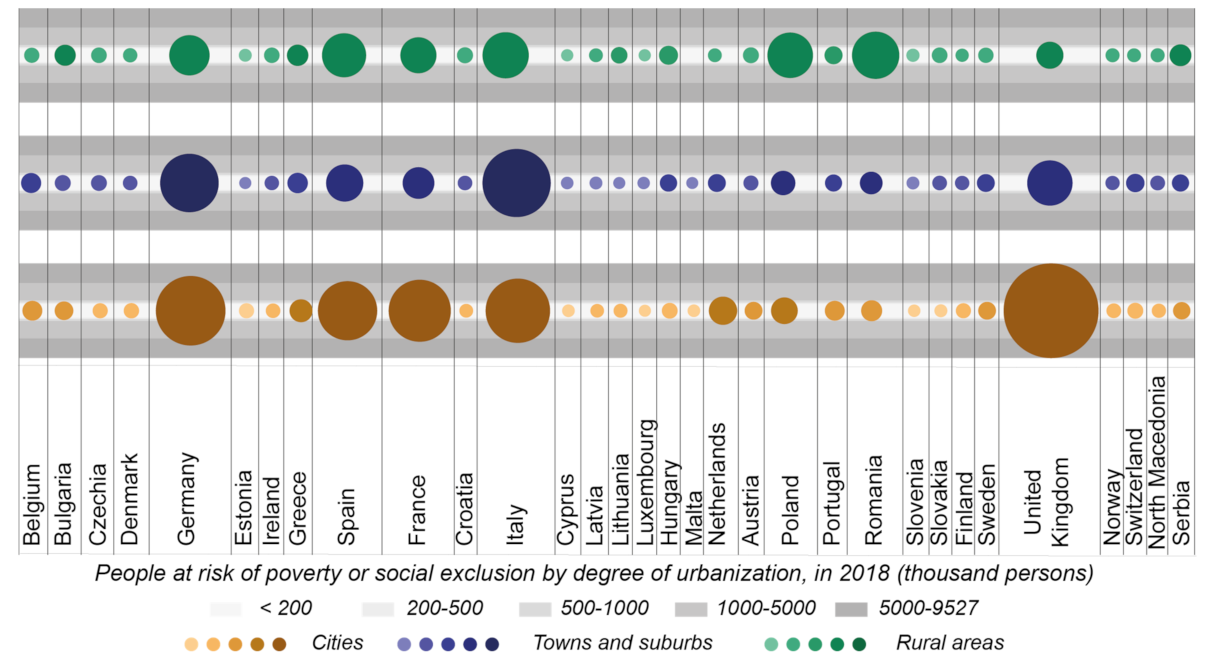

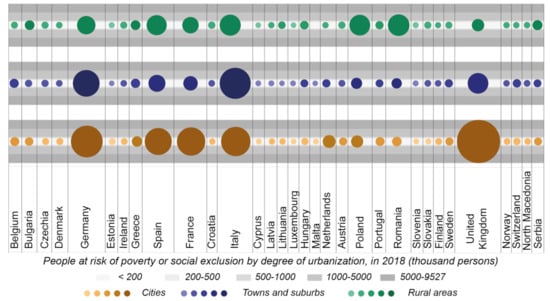

Over the last 20 years, the gap between rich and poor has deepened in the EU Member States, futher translated into the emergence of gated communities and the proliferation of informal settlements and social segregation [23]. In 2018, about 109,151 inhabitants were at risk of poverty and social exclusion [24] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Share of population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by degree of urbanization in 2018. Source of data: EUROSTAT.

Some of the newly created communities are the direct result of housing policies, and the case of Sweden, with The Million Homes Program is illustrative in this sense [13,16]. Housing policies focus on the residential issue, encouraging the construction of dwellings for vulnerable groups, but they do not solve other dysfunctions related to the elimination of urban segregation, namely the lack of real social cohesion or access to certain services [25].

With the same socioeconomic and political background, the states included in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), together with those in Southeast Europe, have gone through a process of transition to market economy, which has also affected housing and property issues. Rapid urbanization, lack of land management policies and increasing poverty have led to the emergence of informal settlements, residential areas without building authorization [26] or urban marginalized settlements in Western European states [27]. They are variably located within cities (inner cities), in the suburban or rural areas or even on contaminated or protected land [26].

1.2. From Marginalization to Urban Regeneration

In recent years, many of the disadvantaged, marginalized communities have been subject to urban regeneration projects, supported by European funding programs and coordinated by local authorities and NGOs, yet some of them contributing even more to the gentrification of inhabitants [28,29]. Participatory neighborhoods are an important aspect for the success of these projects in the regeneration process, which practically means using local knowledge and promoting place leadership as components of local governance [30]. This proves to be much more efficient than adopting a smaller scale solution (city, county, etc.) [31,32]. In other cases, based on the right to the city, citizens are encouraged to participate along specialists in achieving the aimed results [33].

Urban regeneration strategies addressing marginalized communities seek complementary intervention directions, some of them focusing on housing physiognomic changes [34], while others focus on creating middle-class spaces associated with the existing communities [34,35,36,37].

Although public policies include objectives that are mainly related to improving the quality of life in the ghettos, most of the implemented projects focus on the construction of new social housing, a fact that maintains social segregation [38].

1.3. Particularities of Marginalized Housing in Romania

Ever since 1990, extreme poverty in Romania has appeared as a geographical phenomenon, not singular or family-related, and located in rural or urban marginalized areas [1]. Although there are a number of policies that aim at the eradication of poverty, due to social exclusion and marginalization of the Roma communities, implicitly self-marginalization in the case of Romania, community poverty is still very current.

To set up a typology of marginalized areas, three indicators are considered: human capital, employment and living conditions [8]. According to the study conducted by the World Bank [8], urban marginalized areas “have a deficit of human capital, a low level of formal employment and offer unsuitable living conditions”. Those are located within an urban area, they are poor and socially isolated and they are not reflected in the spatial statistics on poverty. Those are mainly recommended as intervention areas for local development projects placed under the responsibility of the community [8,39]. They are considered as slums [40].

Some four subtypes of marginalized urban communities were identified in the research conducted by the World Bank in 2014:

- ghetto-type areas with poor quality blocks of flats or in former low-quality housing facilities for workers, built before 1990 especially to lodge workers employed in large socialist enterprises; many of them are co-owned by landlords and tenants;

- slum areas with unconventional/improvised houses and/or shelters, usually located in old peripheral neighborhoods with improvised houses/huts; sometimes, container houses are placed in their vicinity;

- upgraded social housing areas, established after the implementation of several integrated projects, with better infrastructure and subject to a higher risk of continuous segregation due to the modernization of infrastructure;

- historical (central) areas of the city, nationalized during the communist period, heavily degraded and used as social housing.

- In the case of Romania, informal housing is defined as a group of illegally built and precarious housing, created by voluntary or forced sedentarization of the Roma population [41,42]. The sedentarization of nomadic Roma during the socialist period on the outskirts of urban or rural settlements or in the former Saxon properties has evolved, in many cases, to establishing new Roma communities near to the first established settlements [41].

- Depending on the spatial extent and physiognomy of constructions, we currently find the following types of informal settlements in Romania: (a). groups of new buildings constructed without authorization, (b). improvised or illegally built dwellings, located in built-up areas, (c). groups of temporary and perennial buildings, (d). housing of the Roma communities [41,42].

2. Case Study Selection

Given the issue brought into discussion, four marginalized housing areas in Cluj-Napoca, Timișoara, Baia Mare and Sibiu cities were selected as case studies based on the following similarities:

- their location on the outskirts of cities and/or in buildings classified as historical monuments;

- they are a direct result of local relocation policies;

- they are communities with strong features of ethnic segregation;

- they are inhabited by Roma communities strongly popularized in the national and international press.

3. Methods Used

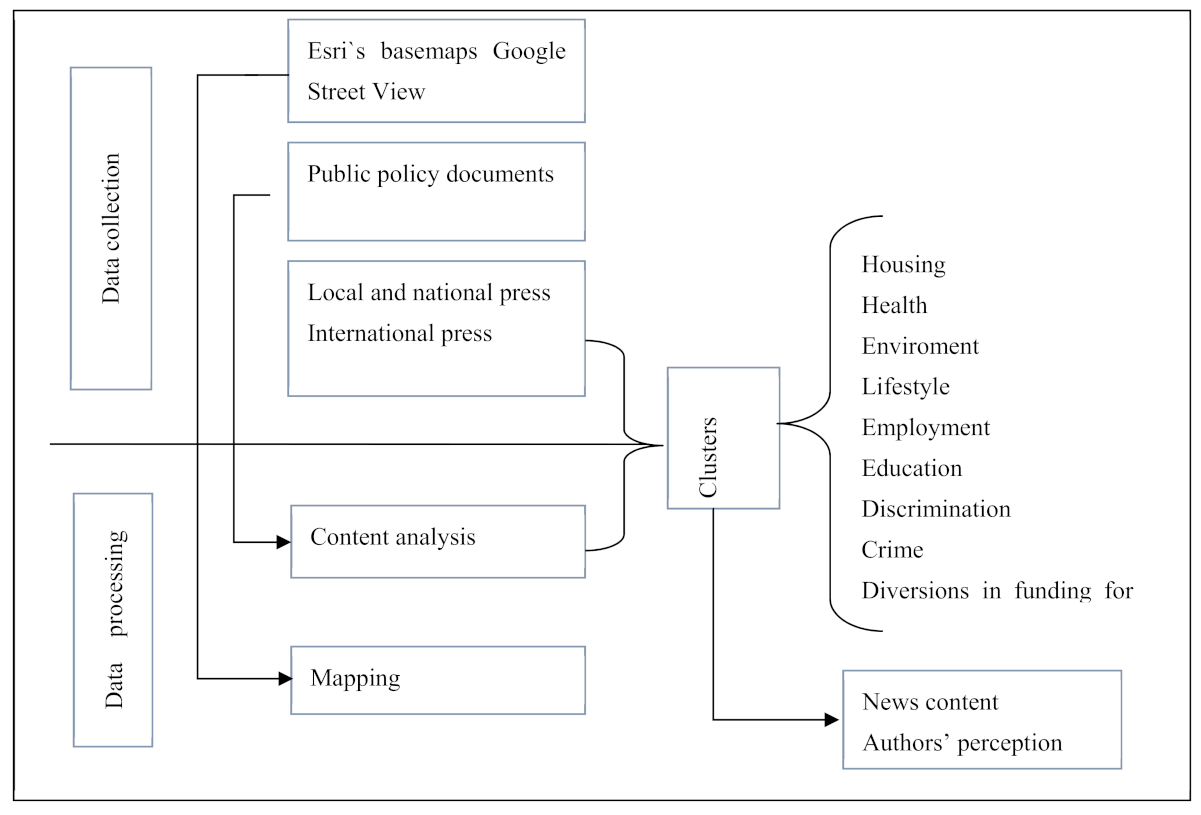

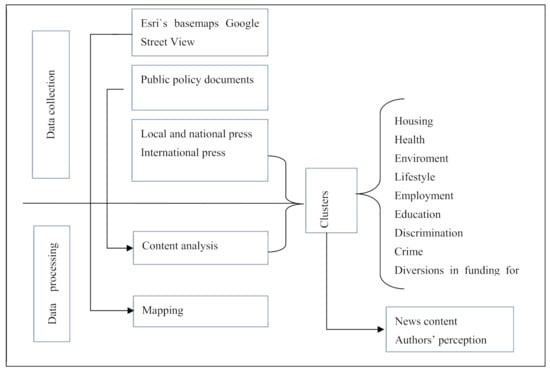

Methodologically, we went through two stages of study to illustrate the mechanisms of structuring and functioning of the four marginalized housing areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the used methodology.

- Data collection involved, on the one hand, the identification of spatial location using ESRI Online resources, OpenStreetMap basemap and Google Street View images that render the physiognomy of the analyzed areas. On the other hand, we selected several public policy documents that regulate the phenomenon of segregation of Roma communities in Romania (laws, action guidelines) and also some local/national and international press articles published in the reference period 2010–2020, which outlined various aspects of the Roma communities under study. Often, the choice of media sources to render the factual reality as objectively as possible proved to be a difficult process as a number of factors intervened, many of them related to the politicization of media, state development level and the dependence of media on various decision makers [43]. Attributes such as intelligibility, popularity, experience and media labelled “traditional” [44,45,46] were considered in selecting media sources that would provide valuable information for this study (Ziar de Cluj, Monitorul de Cluj, Romania Insider, Adevărul, Ziar MM, Turnul Sfatului, Tribuna, Ziua de Vest, Al Jazeera, France 24, The Guardian, BBC, The Sun, Daily Mail, Telegraph, etc.).

- Data processing consisted in mapping the study areas by using ArcGIS 10.7 software and the qualitative and quantitative content analysis of public policy documents and press articles.

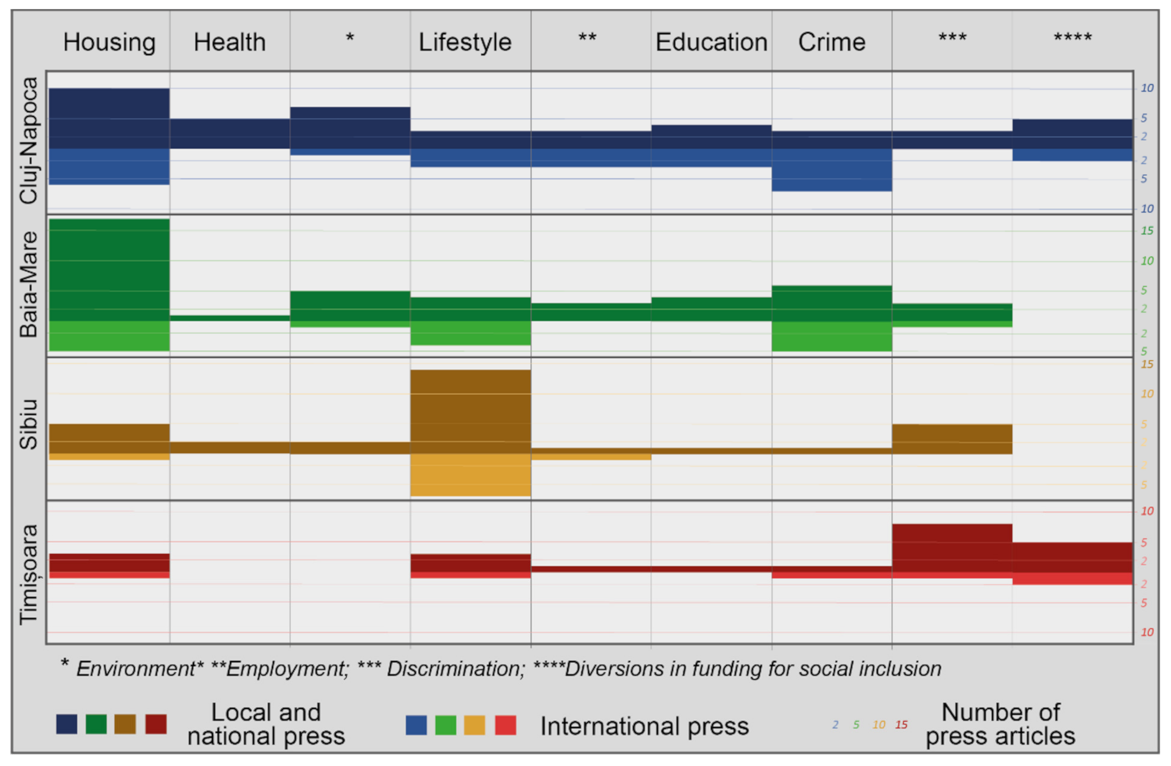

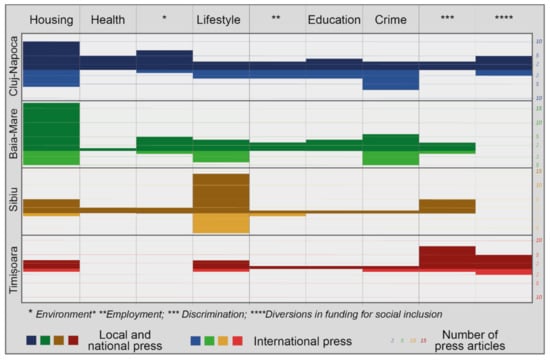

The qualitative analysis of press articles [47,48,49] was performed by organizing their content in clusters, using codes. In content analysis, code classes are assigned to elements that systematically group and create a model that can be applied to several texts in a sample [50]. In all, 110 articles from the local and national media and 40 articles from the international media were assigned codes and subsequently categorized into nine main content categories (Figure 3). Furthermore, to illustrate the complexity of situations that define these four marginalized communities, each class was organized into one to three subcategories.

Figure 3.

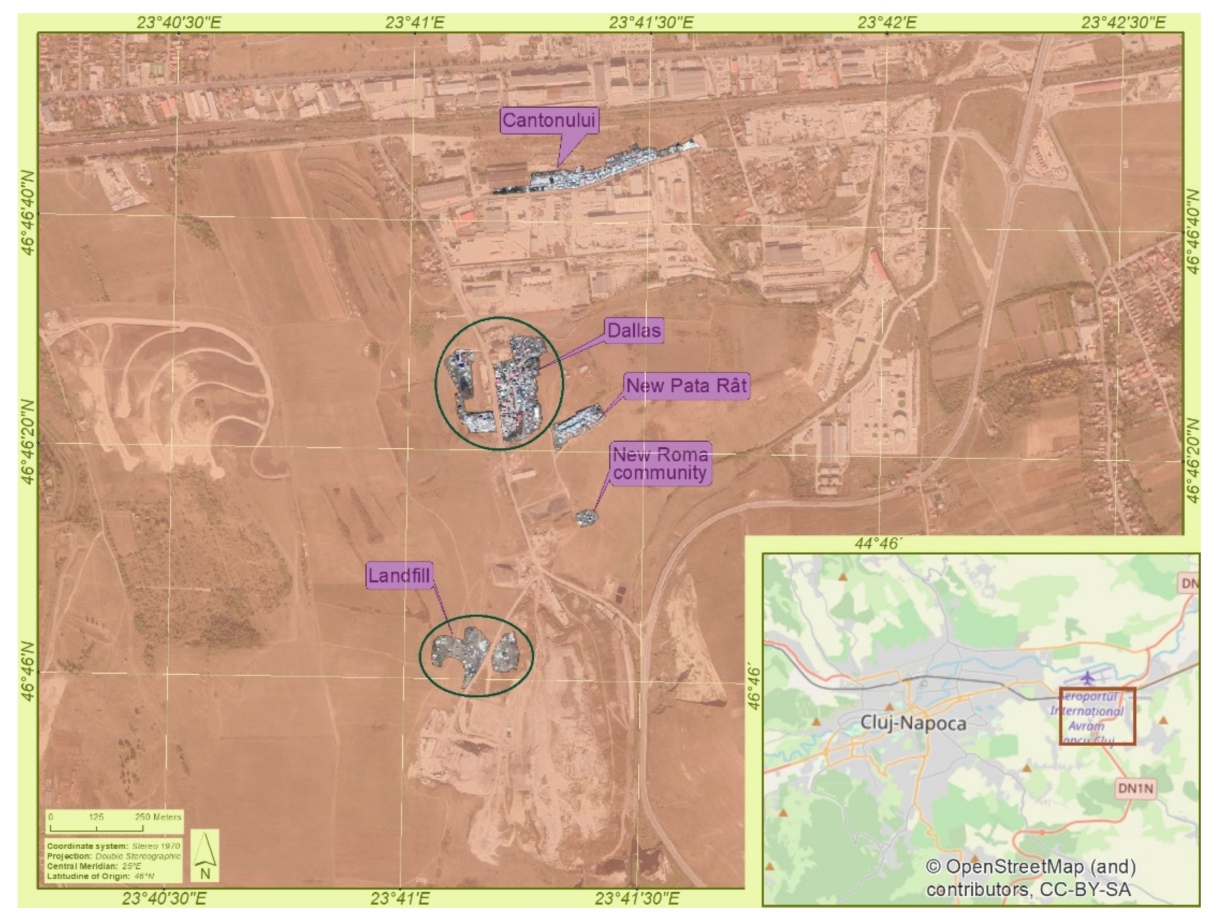

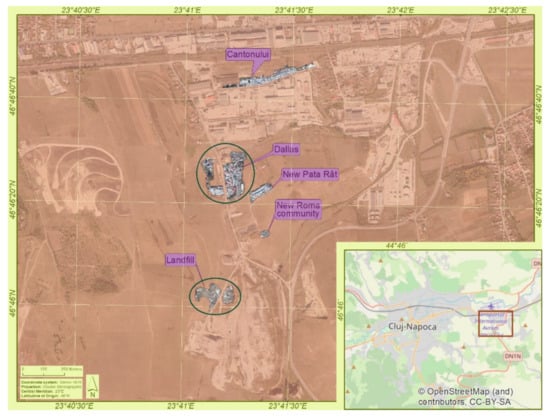

Pata Rât marginal housing area in Cluj-Napoca.

In order to identify frequency trends of topics in the news articles, the nine content categories were quantitatively classified by the cities analyzed and by two types of media, national (including local) and international. In terms of quantitative analysis, the methodology consisted in the correlation of the news content with the types of codes and was achieved by cross-tabulation [51].

Beyond the type of content, the correlation between media content, neutrality and authors was also analyzed. Some studies state that negative information has a greater impact on consumers than positive information [52]. Sentiment content analysis provides an image of the attitude of consumers regarding a product [53]; in the end, content is categorized as positive, negative or neutral.

4. Results

4.1. Marginalized Housing Areas—An Effect of the Local Relocation Policies

Many of the urban and rural settlements in Romania have reported the presence of informal settlements, more or less officially delineated by the local authorities. For the present study, three of the categories of informal settlements proposed in the World Bank report were considered: slum-type areas with houses and/or improvised shelters (Cluj-Napoca, Baia Mare), areas of modernized social housing (Cluj-Napoca) and historical areas within the city (Sibiu, Timișoara). What all four selected case studies have in common is the fact that they occurred because of external factors (i.e., relocation of some families that used to reside in more central areas, restitution of some land and construction properties), and it was not a voluntary spatial choice of the residents of these communities. If, initially, the relocation trend was purely geographical, with residents choosing locations in areas without other real estate pressures, gradually, due to the lack of an integrated approach to housing utilities and services, social marginalization increased.

The spatial relocation of residents has some common features:

- the decisive triggering factor for setting up new spatial locations for the communities is external, completely independent of the actual affected community;

- representatives of these communities had not been involved in any public consultation/debate before the actual relocation process was completed;

- lack in the provision of minimum housing services, which is opposite to the practices conducted in other cases of housing construction in urban neighborhoods;

- a persistent high degree of poverty in these informal settlements, even if specific measures to improve some aspects of the quality of life of the inhabitants were taken.

The first analyzed marginal settlement is that of Pata Rât, in Cluj-Napoca city (Figure 3). It is an intensely publicized informal housing area of about 1500 people. It consists of four colonies, namely: Dallas colony and the colony located on the landfill, both set up in 1960–1970; the colony on Canton Street, formed after evictions from other areas sheltering homeless people; and the New Pata Rât colony (area called “green hill” and Platanilor Street), formed as a result of setting up ten modular houses and the forced relocation of some evicted families from the central city area [54].

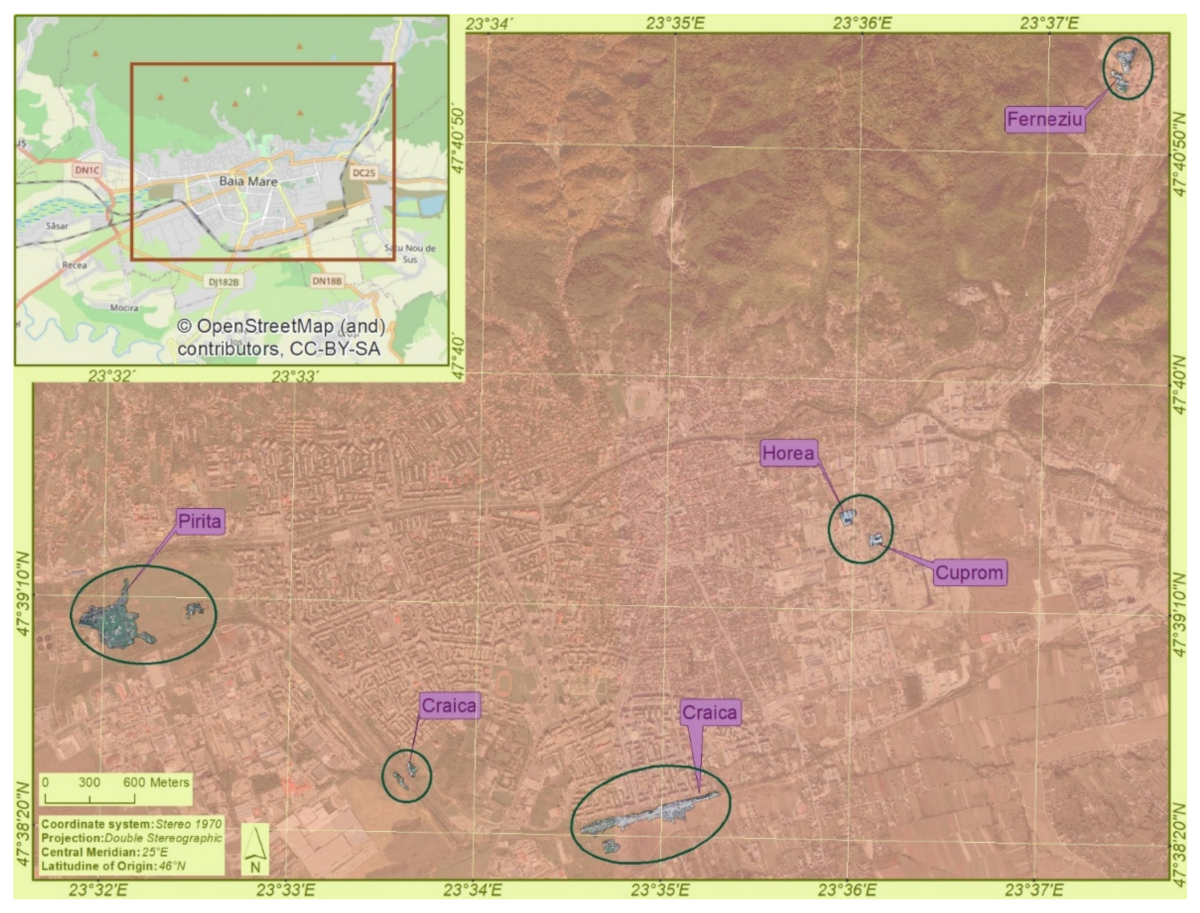

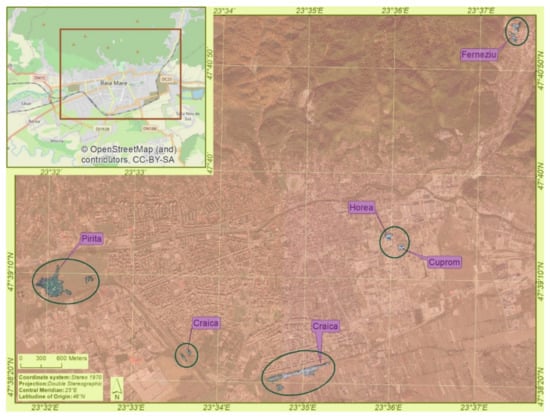

Another informal settlement is located in Baia Mare (Figure 4). It is housing an important Roma community (of approximately 1930 inhabitants) distributed in several spatial concentrations: (a). Craica, where 1110 inhabitants live in improvised and unauthorized dwellings, (b). Cuprom, a Roma community created by the relocation of families from Craica community, (c). Horea, known by the surrounding “wall” built by the mayor of the city, (d). Pirita, where the 200 Roma people live in extreme poverty and (e). Ferneziu, a Roma neighborhood organized near the former Romplumb factory [55].

Figure 4.

Marginal housing area in Baia Mare.

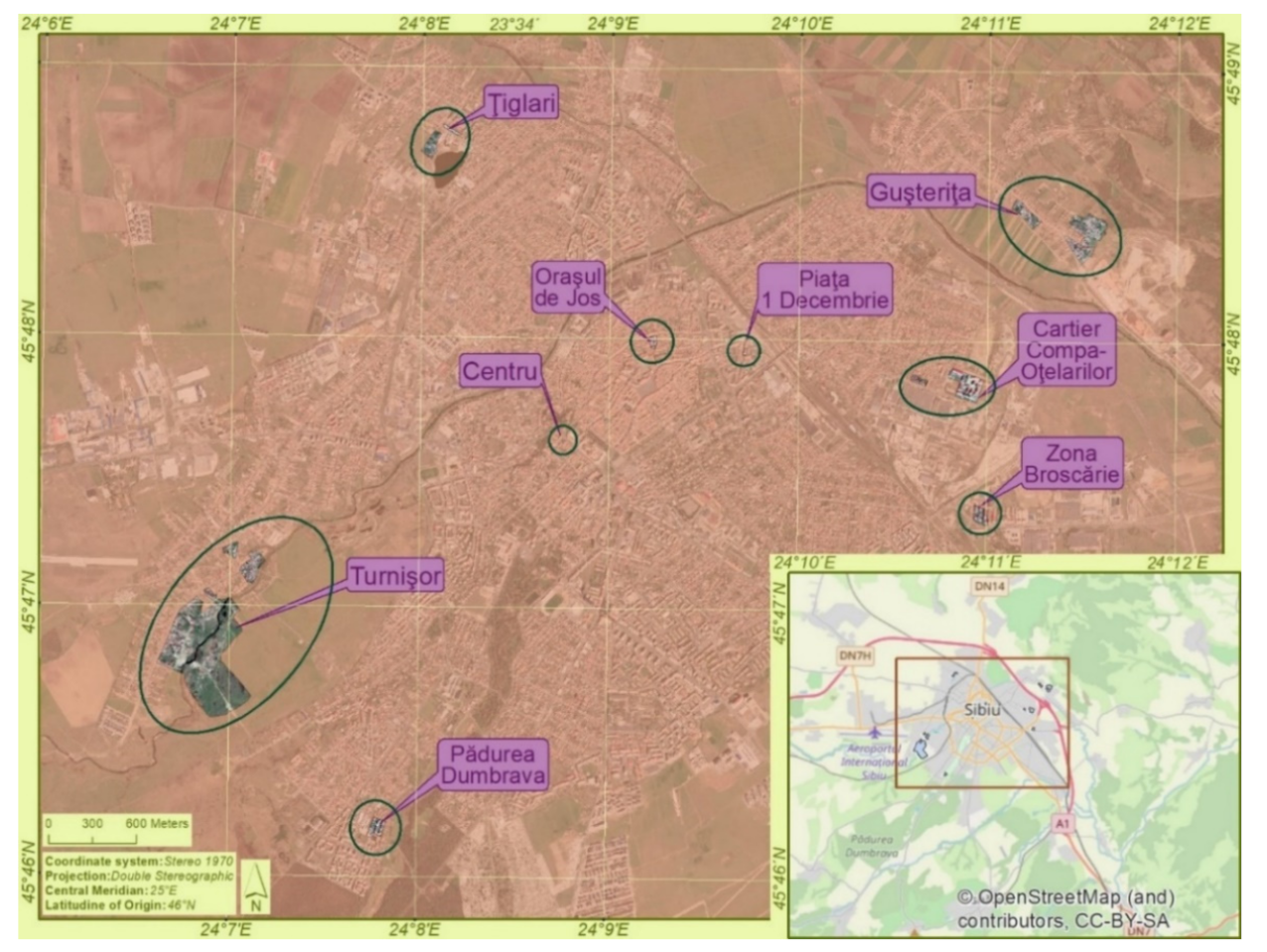

The third case study is Sibiu city, where the Roma communities are found in a double context (Figure 5). On the one hand, there are two slum type housing areas (in the neighborhoods of Turnișor, with about 170 dwellers, and Gușterița, with about 320 people) and a colony with improvised shelters in Țiglari neighborhood (about 50 Roma people), along with ghetto type areas with blocks of flats (the neighborhoods of Țiglari, Broscărie and Compa Oțelarilor). On the other hand, in the city historical center we can also find social housing or abusively occupied historical buildings [8]. It should be noted that Sibiu is also the place where we find the headquarters of the self-proclaimed Royal House of the Roma everywhere.

Figure 5.

Marginal housing area in Sibiu.

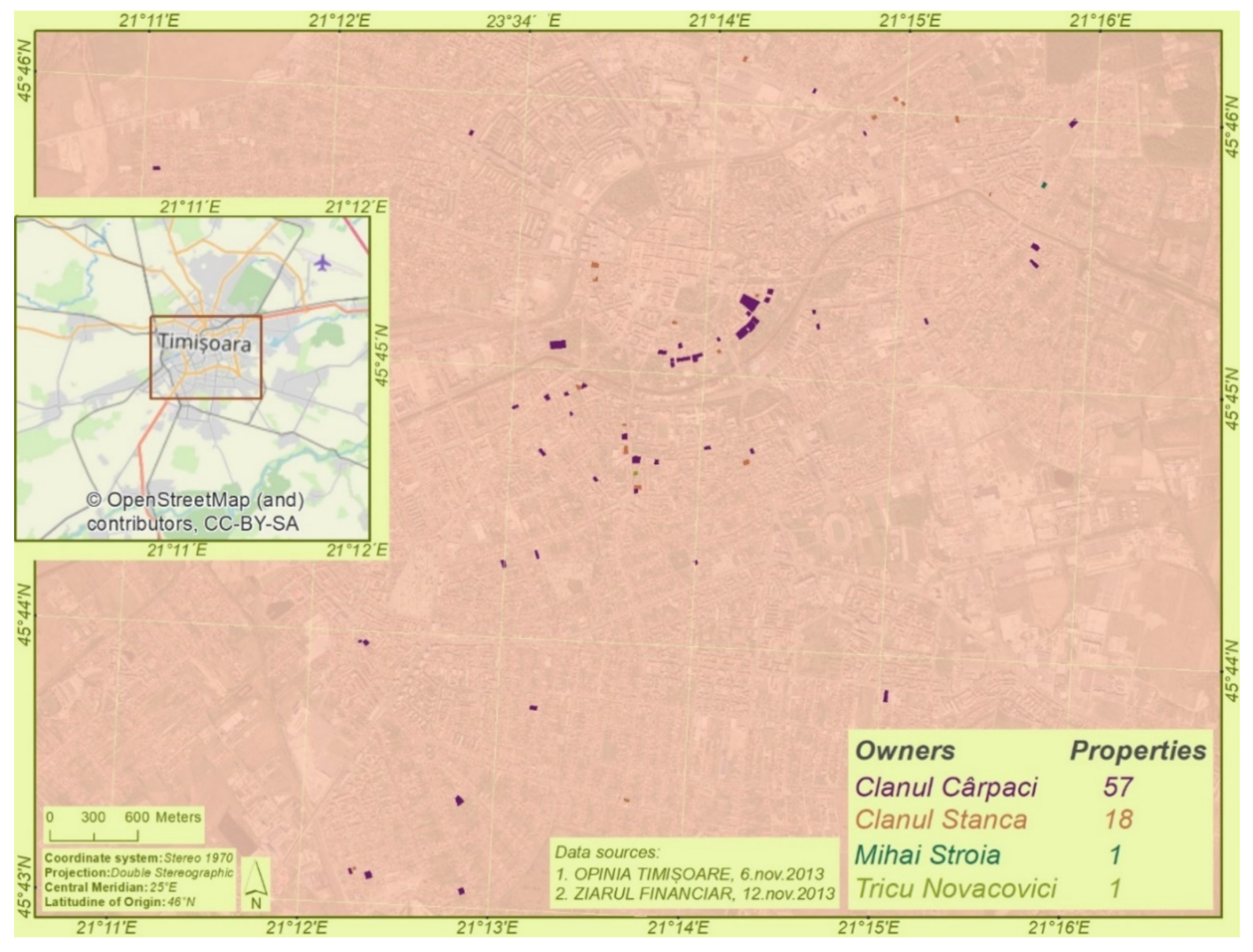

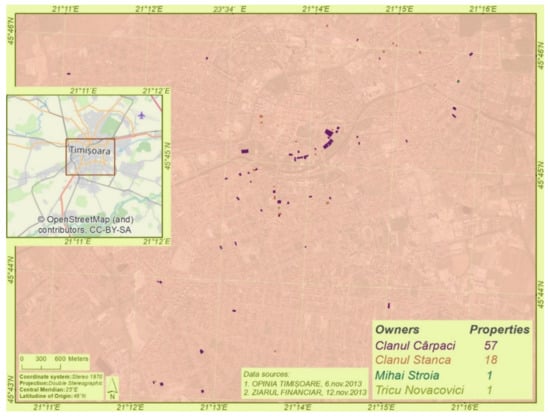

The case of Timișoara is different from the others analyzed (Figure 6). Here, a part of the Roma community, who managed to gain new economic status, has territorially individualized through extravagant housing. It is the case of gypsy palaces with neoclassical influences, located in the city central area, the east train station or along several main roads [56]. In addition, news articles also reported the case of abusive occupation of some historical buildings within the city historical center by the gypsy families, following legal land and building restitution.

Figure 6.

Marginal housing area in Timișoara.

4.2. Faces of Marginalized Housing as Reflected by the Media

The content analysis of news published in the national and international media regarding informal housing areas in these four cities (Figure 7) shows the following particularities:

Figure 7.

Frequency of news regarding informal housing, by content categories.

- an increased interest in the issue of informal housing in Cluj-Napoca (n = 68) and Baia Mare (n = 59), mainly due to the environmental conflicts found in these cases;

- the international news articles predominantly outline problems of the same communities analyzed by the national media, particularly those located in Cluj-Napoca (n = 25) and Baia Mare (n = 16);

- the abusive occupation of some buildings in the historical center of Timișoara by representatives of the Roma clans (n = 9) is a visible topic;

- the extravagant lifestyle associated with the Roma communities in Sibiu (n = 21) is highly debated, as well.

The content found in the media of the last 10 years, specifically related to the Roma communities and marginal housing areas, was assigned codes according to several categories of information, as follows: housing, health, environment, lifestyle, discrimination, education, employment, crime and diversions in funding for social inclusion.

The living conditions of the Roma people are below the standard of other existing communities [40] (Figure 8). The content analysis of the written media (n = 52) highlights several aspects:

Figure 8.

Colony on Canton Street, Cluj-Napoca. Source: Google Street (13 May 2020).

- media is highly interested in outlining initiatives and ways of allocating the necessary resources to improve living conditions (n = 31);

- funding was mostly used for housing purposes, namely the construction of modular houses, social housing or even the modernization of some apartment blocks already resided byRoma ethnics;

- the predominance of kitsch features in the case of gypsy palace architecture in Timișoara (Figure 9) and Sibiu [56,57].

Figure 9. Private house—in the ownership of Mihai family, Timișoara. Source: Google Street (13 May 2020).

Figure 9. Private house—in the ownership of Mihai family, Timișoara. Source: Google Street (13 May 2020).

Recent news reports a variety of information about the Roma communities, especially during the state of emergency in Romania, declared over the COVID-19 outbreak. Some media organizations (Radio Free Europe—Romania) highlight the food products support provided by certain NGOs in Cluj-Napoca to the Roma community at Pata Rât. Others (Monitorul de Cluj, Baia Mare 24, Ora de Sibiu, Libertatea) report the non-compliance of some community individuals with traffic restrictions during the pandemic period (Pata Rât—Cluj-Napoca, Cuprom—Baia Mare, Turnișor—Sibiu) and the registration of infected patients (Turnișor—Sibiu). The precariousness or lack of health services in informal settlements is reported in the national press (n = 11). On the one hand, health problems are reported in colonies from Pata Rât and Sibiu (measles outbreaks, lack of vaccination and cases of COVID-19). On the other hand, there are sporadic mentions related to the initiation of some health projects (e.g., proposal to set up health centers in Baia Mare). Warnings about the existing environmental problems in Pata Rât (Cluj-Napoca) and Cuprom (Baia Mare) have been the subject of several national and international news items (n = 16). Some of them focused on pollution causes (n = 12), while others highlighted sanitation and cleaning actions (n = 4). One of the main problems found in informal settlements is the low level of education. All media materials published in the last decade on education issues of the Roma communities make direct reference to educational inclusion and initiatives launched in this regard at the community level (n = 14). Such projects have been implemented by various NGOs, namely United Way Romania, which built a community center for children in Pata Rât, the Somaschi Volunteer Foundation in Baia Mare or the Community Resource Center in Cluj-Napoca (the campaigns of “People on the fringes of society”, “Raise a director”). A particular aspect debated in the media (n = 12) is job provision for the population living in informal settlements as a result of using available funds supporting inclusive labor markets. A general conclusion is the small number of such projects, the continuity of which is conditioned by their implementation period. The lifestyle of inhabitants in informal settlements (also including the historical buildings used by the Roma for housing) has been subject to a number of testimonies in the media (n = 39), both national (n = 24) and international (n = 15).

Regarding the lifestyle of the Roma community, the following aspects are pointed out:

- elements of oral history, more precisely recordings of stories related to the daily life of Roma communities (n = 17), revealing particular features of traditional crafts and gastronomy and other customs. Xenophobia, discrimination and racism are also highlighted and debated.

- involvement of the Roma ethnics in cultural events (n = 13), mostly in Sibiu; for instance, their active participation in the Astra Multicultural event, the organization of international meetings of Roma poets and artists, the involvement in ”T-aves baxtalo!” event or book launches for Roma authors (Luminița Cioabă);

- presentation of life events, namely weddings and funerals, which follow certain traditional customs (n = 13), promoted especially by the international publications (4 News, Global News, Telegraph, Vice, Daily Mail, The Guardian).

At present, although not in the case of analyzed areas, getting to know the Roma lifestyle has been the starting point of some guided tours, as in the Tzigania Project [58], a community development program. In particular, the international news (n = 13) outlines discriminatory actions to which the Roma ethnics are subject. Moreover, there is higher discrimination against citizens living in areas facing various environmental problems (landfills) [59]. This is also the case in Pata Rât (Cluj-Napoca) and Craica (Baia Mare). Environmental racism is mentioned only in articles published internationally (n = 6). They highlight the unhealthy conditions in which the Roma communities live in Europe, including Pata Rât and Craica, and focus on the important role the local authorities play in creating this situation.

According to the Global Atlas of Environmental Justice (2018), a platform that records ecological conflicts, the cases of Pata Rât and Craica are registered as conflicts [60]:

Hundreds of Roma forced to live in chemical laboratory of the CUPROM copper factory, Baia Mare, Romania—a conflict generated by the decision of the local authority to relocate Roma families from Craica ghetto to the platform of the Cuprom factory. Some 2000 people were affected by this decision. The intensity of conflict was average (street protests, visible mobilization of groups militating against discrimination). This action had a visible environmental impact (soil contamination), health impact (exposure to radiation risk) and socioeconomic effect (relocation, loss of livelihoods, etc.).

- Pata Rât landfill, Cluj-Napoca, Romania—an ecological conflict generated by the relocation of 350 inhabitants from a residential area in Cluj-Napoca to a location near the city waste dump. This decision was made by the local authority and some 1500 people were affected. The intensity of conflict was average (street protests, guerrilla theater, activism, public campaigns). The generated impact was environmental (air pollution, soil contamination, waste discharge, unhealthy housing), socioeconomic (relocation, fires, unemployment) and health related (accidents).

Beyond the discrimination aspects associated with ethnicity, the negative effects of air quality in informal settlements affect the wellbeing of communities [61].

The most wide-ranging content addresses the issue of discrimination against the Roma (n = 18), many comments being caused or amplified by actions of the local authorities or generated by the possibility of relocating the Roma families to other areas (for the statements made about the relocation of the Roma population in Pata Rât, Grigore Fati, the Mayor of Apahida, risks a fine from the National Council for Combating Discrimination, Ziar de Cluj, 2 June 2017). The erection of a concrete wall delimiting the blocks dwelled in by the Roma population was not left without reactions (The Mayor of Baia Mare fined for not demolishing the wall around some Roma blocks of flats, Mediafax, 29 January 2020). There is also news on the discriminatory language against the Roma, highlighted in the US State Department Report. The international press (Amnesty International USA, AL JAZEERA, Liberation, MailOnline) condemns even more intensely the stigmatization and intentional social marginalization of the Roma communities, through forced evictions from homes and their relocation to the outskirts of cities, such as in the case of Craica, Pata Rât, Cuprom. News whose content is related to crime among the Roma communities is another category of information obtained (n = 21). The media highlights three situations:

- records of cases of theft and other crimes (violence, human trafficking, non-compliance with regulations in force) (n = 9) in which ethnics of specific clans (Timișoara) or members of the Roma colonies located on the outskirts of cities were involved;

- conflicts between the Roma and the Romanian communities (n = 10) recorded in Timișoara and Sibiu (Turnișor);

- records of tax fraud and abusive occupation of historical buildings (n = 5), a situation found in Timișoara (Cârpaci, Stancu clans).

We also mention that almost all of the crime aspects are mentioned only by the national press (n = 19), as the international press does not consider this topic as a news subject (n = 2). The existing social policies, and especially the current financial support measures, provide little real support for issues related to education and employment [62]. They are most often focused on the construction of social housing, which, in many cases, leads to an even greater degree of social segregation. Another problem derives from the short terms for project implementation, which limit the sustainability of the proposed interventions and reduces the types of projects that can be managed during that short period. In addition, a stereotype of solutions for addressing issues in informal settlements can be noted.

We also find cases of diversions generated by the allocation of European funds (n = 9), especially the Norwegian grants, for the construction of social housing in Pata Rât.

Sentiment content analysis of the news related to informal housing in cities under study shows that (Table 1):

Table 1.

Correlations between content and perception of author(s).

- content is fairly presented in the media, with predominant tendencies of neutrality regarding the manner of presentation on behalf of authors;

- objectivity is generally maintained between content and its presentation, with some exceptions, usually associated with a tendency of negativism on behalf of author(s) when it comes to the involvement of Roma communities in cultural events;

- most of the positive news refers to the initiation or implementation of social inclusion projects (housing, education, employment);

- the negative features are mostly noted in the news on habitation, environmental racism, crime and ethnic discrimination.

All of the analyzed press articles reflect the public perception on the lifestyle of the residents of these informal settlements. They tend to emphasize more the impact these communities have at the local level rather than finding solutions to improve their quality of life. They focus on identifying the actors responsible for creating these situations instead of proposing new suitable housing policies. The multiculturalism intensely promoted in Romania, through the contribution brought by all the cohabiting minorities, does not exclude the Roma ethnic group, for which reason self-education for all of us should be a continuous exercise in order to treat them with respect and avoid any discriminatory language. On the other hand, the Roma lifestyle, highlighted with a positive touch in the international press, can be the starting point for guided tours within informal settlements.

5. Discussion

Accordingly, studies conducted by UNECE [26,63] validate the presence of informal settlements in East European countries (Table 2).

Table 2.

Written documents associated with marginal housing.

In the case of Romania, the World Bank report (2014) brought its contribution by setting up a typology of marginalized urban areas and their association with ethnic (Roma) communities, while emphasizing the state of these communities. The informal settlements identified in all small and large urban centers in Romania are reported in the Atlas of marginalized urban areas. Here, we can also find their main attributes, as well.

Discussions on the poverty level of some communities and how it is reflected in actions that aim to combat social marginalization have appeared in Romania since 2002, but most measures were general. In 2019, informal settlements have already been regulated at national level, local authorities being obliged to centralize, spatially delimit and maping the spontaneously developed housing groups; if they are located in areas of natural, biological or anthropogenic risk, they may endanger the safety of the inhabitants [64].

Action guidelines have been defined for communities living in informal settlements. Moreover, locally, through the NGO Apartment Block for Housing [65], a guideline framework to prevent forced evictions has been proposed. In terms of spatial planning, the expansion of informal settlements has increased recently, caused either by the lack of urban regulations or by the lack of implementation of existing ones. Beyond the legality of these settlements and their residents (lack of property deeds, lack of identity documents, etc.), the issue of the quality of life remains equally current, particularly relative to housing quality standards. Conditioned in most cases by the existence of external funding, the former development initiatives have demonstrated the lack of a bottom-up or top-down vision that would ensure a continuous and integrated action framework on behalf of the various responsible decision makers; these actions addressed various issues such as the extension of these informal settlements, the regulation of some legal aspects for their functionality or the social integration of marginalized communities and improvement of the quality of life.

At the national level, the functioning management of informal settlements and their recognition as distinct spatial entities requires a regulatory framework that should cover all housing issues. Locally, several measures are needed to be taken such as continuous monitoring, constant updates of any new occurring problems, real and participatory mediation with the local community involved in their social integration and restructuring of interventions within these communities.

The future approaches of informal settlements should consider the following aspects:

- keep an updating record on the expansion or occurrence of new informal settlements, their number of inhabitants and the main housing features in these areas, based on data provided by the 2021 National Census of Population and Housing;

- set up local working groups to specifically focus on housing;

- create local housing policies;

- devise and implement development projects aimed at reducing or combating poverty and social exclusion, which is a priority of the European policy and Agenda 2030; a new EU financial mechanism will be available for the period 2021–2027 (European Union Territorial Cohesion Policy Objective—A more social Europe [69]).

6. Conclusions

In the case of metropolitan and urban areas in Romania, the outskirts of cities become the intended location for marginal housing, whether we consider the relocations proposed by the local authority or the ad hoc improvised housing, with minimum living conditions, initiated by communities. Although informal settlements are officially acknowledged and authorities have elaborated certain intervention guidelines for different categories of local stakeholders, they are still quantitatively limited, in terms of implementation efficiency and message conveyed. Another aspect to be noted is the lack of spatial and statistical delimitation of marginal housing, as it is usually not updated in the records of the local authorities. Thus, legal acknowledgement should be a priority, along with setting up suitable measures with impact on housing, health and socioeconomic status of their inhabitants.

Representations of informal settlements in the media have had and still have an impact among the communities involved. They also contribute to the change in the general perception of citizens regarding the living conditions and social marginalization of the dwellers. Unfortunately, a series of negative aspects that define this type of settlement is visible in the public perception, in some cases a certain kind of hate speech being maintained/obvious. The analysis of media articles, whose topics were related to informal settlements and housing, reflects a positive attitude of the civil society and an active involvement of the NGOs.

In some cities, Cluj-Napoca for instance, certain NGOs that aim to improve the quality of life of Roma communities in Pata Rât, and fight against ethnic discrimination (Social Homes, PataCluj, Desire Foundation, Amare Phrale, etc.) have continuously been working for several years and created projects specifically for them (Social Housing NOW project), including a series of street actions against the ghettoization of the Roma population and their relocation in unsanitary conditions, and the initiation of public debates on the identification of housing solutions.

Although there are some initiatives to raise awareness on increasing social housing in the public housing stock (Cluj-Napoca, Baia Mare), their number is far from sufficient, and there is a difficult and long-lasting road from funding to construction and relocation. Public perception, as reflected by the media, highlights the role that decision makers should play as representatives of the public authorities, a role that is often only partially performed and only with short-term effects.

However, the very attitude of the residents of the marginalized areas decisively contributes to the low functionality of these housing areas. Thus, the general population still shows a discriminatory attitude towards the Roma individuals, this mentality being most often fueled by the non-compliant actions of this ethnic group.

Another feature of the Roma communities, also involving a high degree of segregation, lies in the lifestyle of the ethnics with an above average financial level, particularly reflected by the gypsy palaces (Sibiu, Timișoara). In addition to these, Timișoara is a particular case. Here, the historical center has become the property of the Roma clans, the media reporting a series of cases of abusive occupation of historical buildings. Beyond ownership status, many of these buildings are classified as historical monuments, which brings obligations to any owner, regardless of ethnicity, to maintain the architecture, preserve and not damage the building.

In addition, the implementation of social inclusion projects, intended mostly for building new social housing, seems to be the least inclusive measure for these inhabitants, many actions being limited to construction without ensuring the minimum housing services.

At present, there is still no common/shared dialogue to reflect the interests of those affected and those responsible. We can still find low participatory involvement of the affected local communities, with a few exceptions in the case of large urban centers, and lack of vision regarding poverty eradication despite the global and European objectives to increase and promote the sustainable development of the disadvantaged communities.

In this research, limitations are given by the use of a finite number of media resources, although considered representative for the topic under discussion, while the credibility of the sources used could not be controlled. Authors’ neutrality is reflected by their perception, but without employing a computerized method, it may be slightly altered by subjectivism. Regarding the selection of case studies, the most representative communities in terms of marginal housing were chosen, therefore the authors are not claiming a comprehensive and generalized approach.

Author Contributions

All authors, G.-G.H., A.-M.P. and A.-C.M.-P., contributed equally to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this article was supported by the 2020 Development Fund of the Babeș-Bolyai University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank. Atlas of Marginalized Rural Areas and Local Human Development in Romania; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, G.; Kollmair, M. Marginality: Concepts and Their Limitations. IP6 Working Paper, 2005, No. 4. Available online: http://nccr-north-south.ch/Pages/Marginality---Concepts-and-their-Limitations.aspx (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Kaya, I.; Zengel, R. A Marginal Place for the Gipsy Community in a Prosperous City: Izmir, Turkey. Cities 2005, 22, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelc, S. Marginality and Marginalization. In Societies, Social Inequalities and Marginalization, Perspectives on Geographical Marginality; Chand, R., Nel, E., Pelc, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Colini, L. Exclusion, Marginalization and Peripheralization. Conceptual Concerns in the Study of Urban Inequalities. Working Paper, 2013, no. 49. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/228579/1/irs-wp49.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Barry, B. Social Exclusion, Social Isolation, and the Distribution of Income. In Understanding Social Exclusion; Hills, J., Le Grand, J., Piachaud, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Atlas of Marginalized Urban Areas in Romania; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Poverty and Employment: The Situation of the Roma in 11 EU Member States, Roma Survey, Brief Data. 2016. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2014-roma-survey-dif-employment-1_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Sandu, D. Roma Communities in Romania. A map of Community Poverty through the PROROMI Survey; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonam, C.M.; Taylor, V.J.; Yantis, T.Y. Racialized physical space as cultural product. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L.; Arbaci, S. The Challenges of Understanding Urban Segregation. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L. The Spatial Syntax of Urban Segregation. Prog. Plan. 2007, 67, 205–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, L. Divided Landscape: The Visual Culture of Urban Segregation. Landsc. J. 2016, 51, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T. Divided Tokio. Disparities in Living Conditions in the City Center and the Shrinking Suburbs; Springer: Tsukuba, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Legeby, A. Urban Segregation and Urban Form. From Residential Segregation to Segregation in Public Spaces. Bachelor’s Thesis, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, A. Inner Suburbs; Orum, A.M., Ed.; The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Airgood-Obrycki, W.; Bernadette Hanlon, B.; Rieger, S. Delineate the U.S. Suburb: An Examination of how Different Definitions of the Suburbs Matter. Urban Aff. 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sika, P.; Vidová, J.; Rievajová, E. Regional View on Housing of the Marginalized Roma Population in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkema, C. “If You Can’t Hear Me, I Will Show You”: Insurgent Claims to Public Space in a Marginalized Social Housing Neighborhood in France. Space Cult. 2019, 22, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, J.-P. Une violence éminemment contemporaine [An eminently contemporary violence]. Espaces Sociétés 2007, 1–2, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, V.; Seminara, M.R. Europe 2020 Strategy and New Policies for Marginal Areas. Adv. Eng. Forum 2014, 11, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Future of Cities. Opportunities, Challenges and the Way Forward; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets//t2020_50?fbclid=IwAR2diY7fbQYXzfbcxZ2fC8lHt3BFYFD-pfWE1FtZtSCAMcvEM4GElM767ms (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Maffini, A.L.; Maraschin, C. Urban Segregation and Socio-Spatial Interactions: A Configurational Approach. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Informal Settlements in Countries with Economies in Transition in the UNECE Region; Background Paper for the Preparation of Potential Technical Guidelines on Informal Settlements in the UNECE Countries with Economies in Transition (EECCA and the Western Balkans); UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Marginality in the Coming Millennium. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Measuring Gentrification and Displacement in Greater London. Urban Stud. 2020, 37, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cin, M.M.; Egercioglu, Y. Change of Daily Life Practices in Disadvantages Groups Settlement through Urban Regeneration. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mullins, D.; Van Bortel, G. Neighbourhood Regeneration and Place Leadership: Lessons from Groningen and Birmingham. Policy Stud. 2010, 31, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurson, K. Neighbourhood Regeneration: Facilitating Community Involvement. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eunji, W.; Chorong, K.; Ki-Young, N. The Journey of Local Knowledge Toward Designing Neighbourhood Regeneration. In Proceedings of the Academy for Design Innovation Management, Conference 2019, London, UK, 18–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maununaho, K. Political, Practical and Architectural Notions of The Concept of the Right to the City in Neighbourhood Regeneration. Nordic J. Migr. Res. 2016, 6, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardo, F.; Oel, C.; Jong, P. Neighbourhood Regeneration by Façade Redesign: A Visual Experiment on Energy Efficiency and Aesthetics. Int. J. Architecton. Spat. Environ. Des. 2013, 6, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N.; Hastings, A. Housing and Neighbourhood Regeneration. Housing and Public Policy in Post-Devolution Scotland; Sim, D., Ed.; CIH: Coventry, UK, 2004; pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent, W.P.C. The Context of Neighbourhood Regeneration in Western Europe. A Comparative Study of Nine Neighbourhoods Undergoing Physical and Social Economic Regeneration; AMIDSt, Universiteit van Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent, W.P.C. Housing Context and Social Transformation Strategies in Neighbourhood Regeneration in Western European Cities. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2010, 10, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berescu, C. The Rise of the New European Roma Ghettos: A Brief Account of some Empirical Studies. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teșliuc, E.; Grigoraș, V.; Stănculescu, M. Studiu de Fundamentare Pentru Strategia Națională Privind Incluziunea Socială și Reducerea Sărăciei 2015–2020 (Substantiation Study for the National Strategy on Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction 2015–2020); World Bank Group: Bucharest, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, D. The Modern Mahala: Making and Living in Romania’s Postsocialist Slum. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suditu, B.; Vâlceanu, D.G. Informal Settlements and Squatting in Romania: Socio-spatial Patterns and Typologies. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 7, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACT Foundation. Informal Housing in România. Research Report. 2018. Available online: http://locuireinformala.ro/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/OSI_Research-report_Informal-Housing-in-Romania_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Fisher, C. News Sources and Journalist/Source Interaction. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Measuring Social Media Credibility: A Study on a Measure of Blog Credibility, Ketchum Excellence. In Public Relations Research Award; Institute for Public Relations, Syracuse University: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allgaier, J. Who is having a voice? Journalists’ selection of sources in a creationism controversy in the UK press. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Alfani, S.; Sassi, M.; Cinini, A.; Calamusa, A. Mass media health information: Quantitative and qualitative analysis of daily press coverage and its relation with public perceptions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 83, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, K.; Bujalski, M. The legal highs problem in the Polish printed media: Actors, claims, and its hidden meanings. Subst. Use Misuse 2013, 48, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribke, N. Global Maladies, Local in Treatment: “Quality” TV Fiction Formats, Local Forms of Prestige, and Cumulative Cross-Cultural Dialogues. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 2056–2073. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, N.M.; Sun, J.; Hong, J.W. Anthropomorphizing AlphaGo: A content analysis of the framing of Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo in the Chinese and American press. AI Soc. 2019, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthers, J.; Kohring, M. The Content Analysis of Media Frames: Toward Improving Reliability and Validity. J. Commun. 2008, 58, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibois, P. An Order on Cross-Tabulations and Degrees of Association. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 2013, 119, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, T.; Hoffman, E. eWOM and the Importance of Capturing Consumer Attention within Social Media. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Haroon, M.; Altaf, O.; Awan, S.M.; Asghar, A. Sentimental Content Analysis and Prediction of Text. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Technologies and Applications, Second International Conference, INTAP 2019, Bahawalpur, Pakistan, 6–8 November 2019; Bajwa, I.S., Sibalija, T., Jawawi, D., Eds.; Revised Selected Papers. Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dohotaru, A.; Harbula, H.; Vincze, E. Pata; Edit. Efes: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hetea, E.R. Raport cu Privire la Situația Comunităților de Romi Din Baia Mare (Craica, Cuprom, Horea, Pirita și Ferneziu). Institutul Pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale (Report on the Situation of Roma Communities in Baia Mare (Craica, Cuprom, Horea, Pirita and Ferneziu), Institute for the Study of National Minority Issues). 2012. Available online: https://ispmn.gov.ro/uploads/Evaluare%20situatie%20Baia%20Mare_Recomandari_EHetea.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Gräf, R. Palatele Țigănești. Arhitectură și Cultură. Institutul Pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale (Gypsy Palaces. Architecture and Culture); Working Papers; no. 9; Institute for the Study of National Minority Issues: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Preda, M.-D.; Vijulie, I.; Lequeux-Dincă, A.I. The Palace Architecture of the Roma Population in Romania. East. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 24, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzigania Project-We Are Taking Down Walls and Building Bridges. Available online: http://tzigania.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Pulido, L. Environmental Racism. In The International Encyclopedia of Geography; Richardson, D., Castree, N., Goodchild, M.F., Kobayashi, A., Liu, W., Marston, R.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Bene, D.; Martinez-Alier, J. Mapping the frontiers and front lines of global environmental justice: The EJAtlas. J. Political Ecol. 2015, 22, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, C.; Charles, A. Community Wellbeing: The Impacts of Inequality, Racism and Environment on a Brazilian Coastal Slum. World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Málovics, G.; Creţan, R.; Méreine-Berki, B.; Tóth, J. Socio-environmental Justice, Participatory Development, and Empowerment of Segregated Urban Roma: Lessons from Szeged, Hungary. Cities 2019, 91, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Formalizing the Informal: Challenges and Opportunities of Informal Settlements in South-East Europe; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Parliament. Law No. 151/2019 for the Completion of Law no. 350/2000 on Spatial Planning and Urbanism; Official Gazette, Part I, 29 July 2019; Romanian Parliament: Bucharest, Romania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Housing Block. Guide for the Prevention of Forced Evictions and the Accountability of Public Authorities in Order to Allocate Adequate Housing to Evacuees; Housing Block: Hong Kong, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Protection and the Elderly. National Strategy on Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction 2015–2020, Official Gazette, Part, I. no. 463 of 26 June 2015. Available online: http://www.mmuncii.ro/j33/images/Documente/Familie/2016/StrategyVol1EN_web.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Romanian Parliament. Law No. 292 of December 20, 2011; Official Gazette, Part I, no. 905 of 20 December 2011; Romanian Parliament: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Romania. Law No. 116 of 15 March 2002 on Preventing and Combating Social Marginalization; Official Gazette, Part I, 20 March 2002; Romanian Parliament: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Territorial Cohesion Policy Objective—A more social Europe 2021–2027. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/2021_2027/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).