How Can We Mitigate Power Imbalances in Collaborative Environmental Governance? Examining the Role of the Village Facilitation Team Approach Observed in West Kalimantan, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description and Objectives

3. Methods

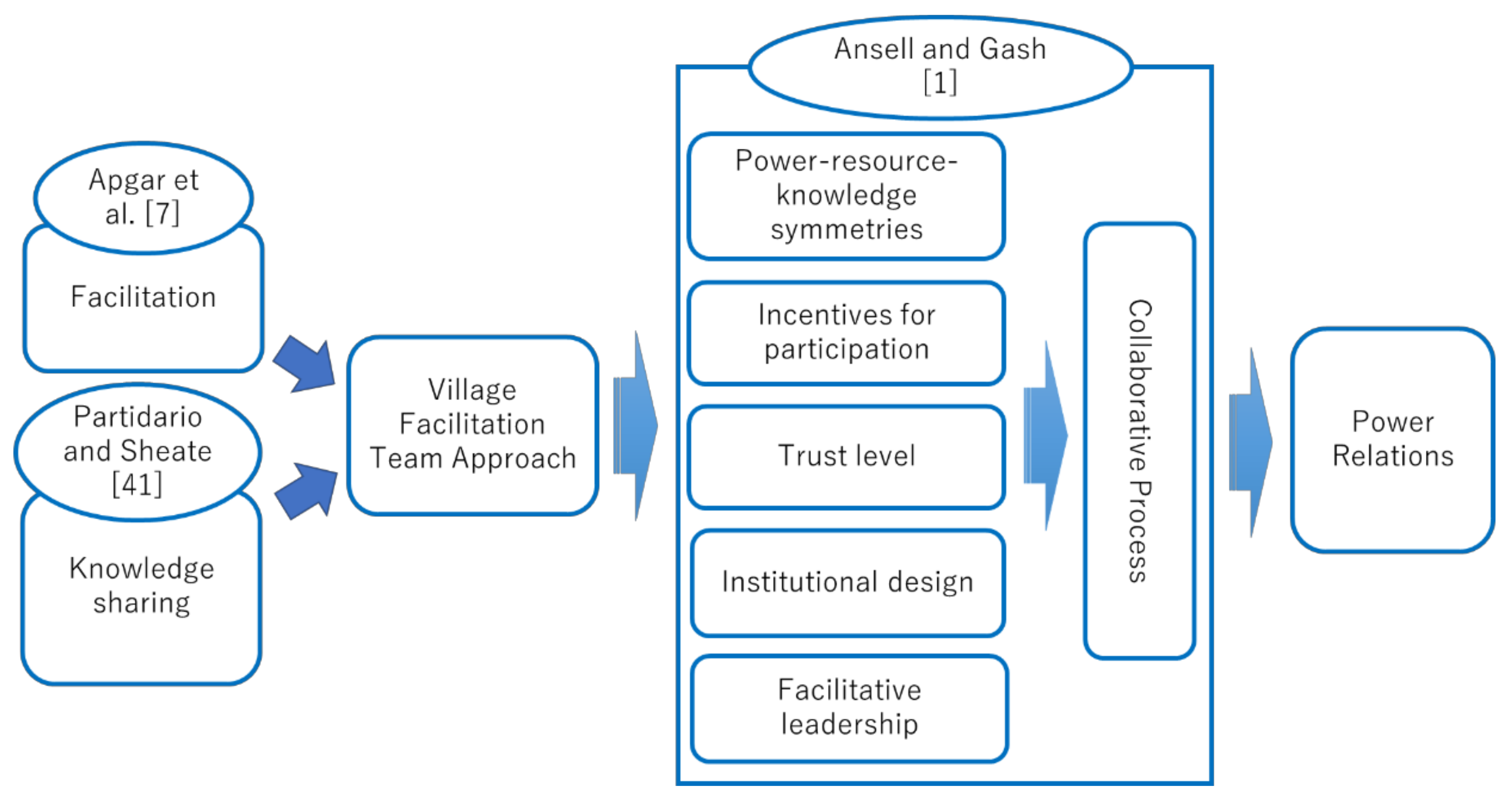

3.1. Analytical Framework

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results and Discussions

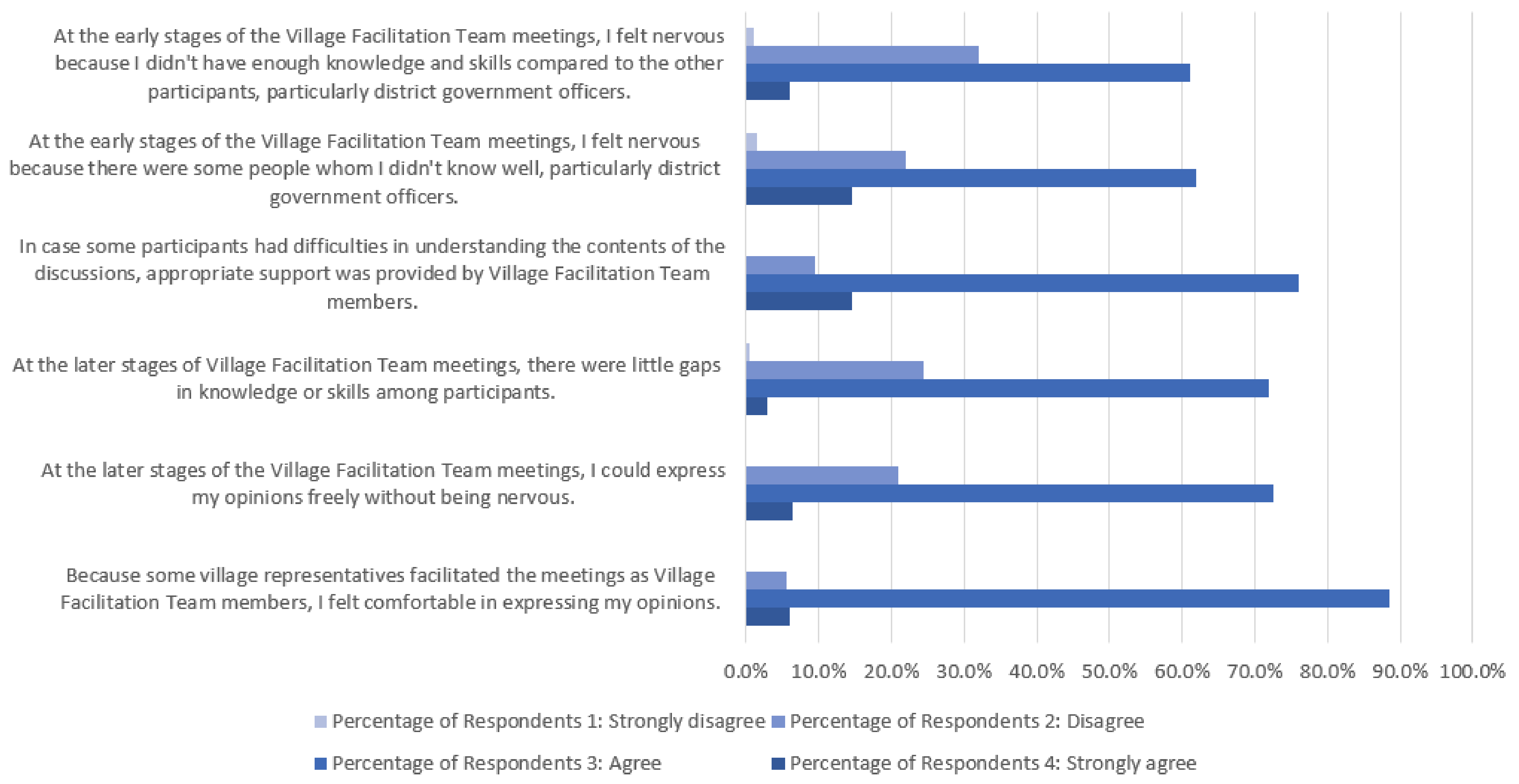

4.1. Power–Resource–Knowledge Asymmetries

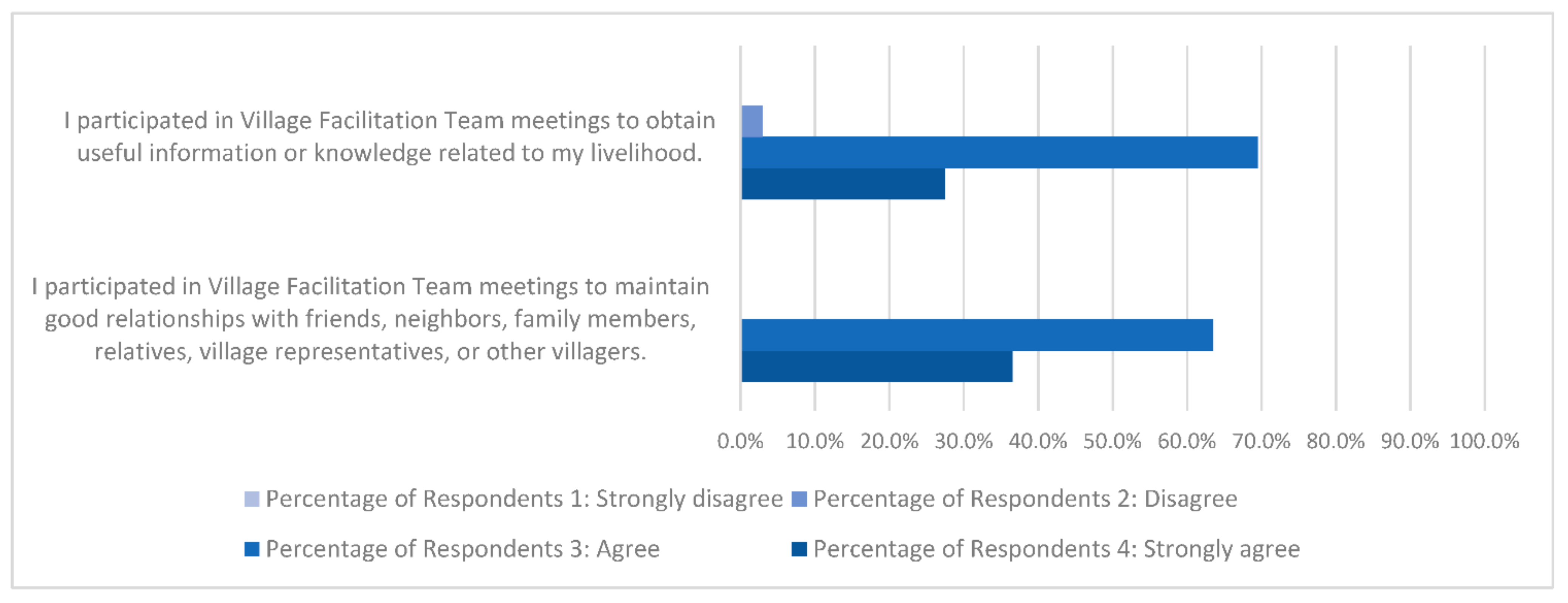

4.2. Incentives for and Constraints on Participation

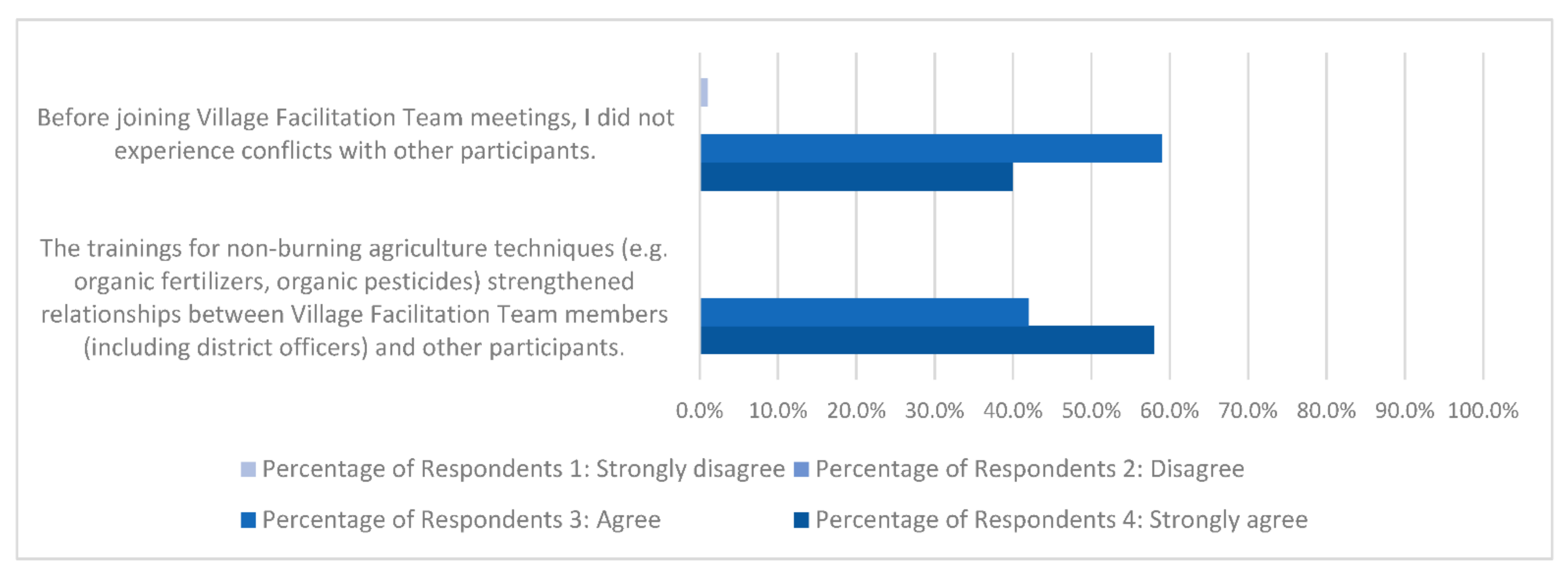

4.3. Prehistory of Cooperation or Conflict (Initial Trust Level)

4.4. Institutional Design (Participatory Inclusiveness, Process Transparency, Clear Ground Rules, and Forum Exclusiveness)

4.5. Facilitative Leadership (Including Empowerment)

4.6. Collaborative Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Outline of the Training Programme for the Village Facilitation Team

| Day | Programme | Style |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Ice Breaker, Self Introduction | Exercise |

| Introduction to Forest and Land Fire | Lecture | |

| Climate Change Mitigation through Forest and Land Fire Prevention | Lecture | |

| Laws and Regulations on Forest and Land Fire | Lecture | |

| Basics of Facilitation and Communication, Concept of Village Facilitation Team | Lecture/Exercise | |

| Day 2 | Participatory Land Use Mapping | Lecture |

| Making a Village Land Use Map | Exercise | |

| Land Management Planning | Exercise | |

| Developing Village Ordinance for Fire Prevention | Exercise | |

| Day 3–5 | Collecting Information of Villages | Field Exercise |

| Interview to Villagers and Farmer Groups | Field Exercise | |

| Implementing Focus Group Discussions | Field Exercise | |

| Facilitation of Village Meetings | Field Exercise | |

| Day 6 | Presentation on Outcomes of the Field Exercise | Presentation |

| Discussion on Outcomes of the Field Exercise | Discussion | |

| Feedback from the Trainer and Other Participants | Discussion | |

| Day 7–8 | Agricultural Practices without Land Burning | Lecture |

| Techniques for Making Organic Fertilizers/Pesticides/Herbicides | Field Exercise | |

| Promoting Business in Villages/Diversifying Agricultural Products | Lecture/Exercise | |

| Fire Prevention Techniques | Lecture/Field Exercise | |

| Discussion on Non-Burning Agriculture Techniques and Business | Discussion | |

| Day 9–10 | Preparation for Facilitation in Project Target Villages | Exercise |

| Presentation on the Plan for Facilitation in Project Target Villages | Presentation | |

| Feedback from the Trainer and Other Participants | Discussion |

Appendix B. Interview Protocol

- (1)

- Did you participate in the VFT meetings?

- (2)

- Why did you decide to participate in the VFT meetings?

- (3)

- How often/how long did you participate in the VFT meetings?

- (4)

- Who were the attendants of the VFT meetings?

- (5)

- How did you feel when you first attended the meetings?

- (6)

- Did you experience any conflicts with other participants before the VFT meetings?

- (7)

- Among meeting participants, were there anybody with whom you were not familiar?

- (8)

- How did you feel when attending the meetings together with other participants, particularly district government officers?

- (9)

- Did the relationship with other participants, particularly district government officers, change over time through the meetings? If yes, how did it change?

- (10)

- What do you think about the training for non-burning agriculture techniques (e.g. organic fertilizers, organic pesticides)? Was it useful or not?

- (11)

- Were the VFT meetings open to everybody or were they restricted to certain groups of people?

- (12)

- During the VFT meetings, was the information shared equally among all participants?

- (13)

- During the VFT meetings, were participants’ opinions listened to and respected by other participants?

- (14)

- Could you understand all the discussions during the VFT meetings? Were there any difficulties in understanding the content of the discussions?

- (15)

- Did you experience any conflicts during the VFT meetings?

- (16)

- How were the VFT members facilitating the discussions?

- (17)

- How were the decisions made during the VFT meetings?

- (18)

- Were there clear rules on how to participate in the VFT meetings?

- (19)

- Did you feel any gaps in knowledge or skills between villagers and district government officers?

- (20)

- If yes, did you feel that the gaps in knowledge or skills changed over time?

- (21)

- If yes, how did they change over time?

- (1)

- Did you participate in the facilitation training programme?

- (2)

- Who were the participants of the facilitation training?

- (3)

- Was there anybody with whom you were not familiar?

- (4)

- How did you feel when participating in the facilitation training together with other participants, particularly district government officers?

- (5)

- How was your relationship with district government officers at the beginning of the training?

- (6)

- Did the relationship with other participants, particularly district government officers, change over time through the training? If yes, how did it change?

- (7)

- What did you think about the content of the training? Was it useful or not?

- (8)

- What kinds of skills/knowledge did you learn from the training programme?

- (9)

- Could you understand the content of the training? Were there any difficulties in understanding the content of the training?

- (10)

- Do you think there were gaps in knowledge or skills between villagers and district government officers?

- (11)

- Was the information or knowledge equally shared with all participants during the facilitation training?

- (12)

- Did you feel that the gaps in knowledge or skills changed over time? If yes, how did they change over time?

Appendix C. Questionnaire Survey Sheet

| No. | All/VFT 1 | Statements | Choices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4: Strongly agree | 3: Agree | 2: Disagree | 1: Strongly disagree | |||

| 1 | VFT | At the beginning of the facilitation training, I felt nervous because I was not confident in my knowledge and skills, compared to the other participants, particularly district government officers. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | All | At the early stages of the VFT meetings, I felt nervous because I didn’t have enough knowledge and skills compared to the other participants, particularly district government officers. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | All | At the early stages of the VFT meetings, I felt nervous because there were some people whom I didn’t know well, particularly the district government officers. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | VFT | During the facilitation training, all the participants had equal opportunities to obtain knowledge and skills. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | VFT | Through the facilitation training, I could obtain abundant new knowledge and practical skills. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | VFT | In case some participants had difficulties in keeping up with the training program, appropriate support was provided by the trainers. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 8 | All | During the VFT meetings, information and knowledge were equally shared with all participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | All | In case some participants had difficulties in understanding the contents of the discussions, appropriate support was provided by VFT members. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 10 | All | I understood almost everything regarding the topics discussed during VFT meetings. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | All | At the later stages of VFT meetings, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 12 | All | At the later stages of VFT meetings, I could express my opinions freely, without being nervous. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 13 | All | Because some village representatives facilitated the meetings as VFT members, I felt comfortable in expressing my opinions. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 14 | All | I participated in VFT meetings to obtain useful information or knowledge related to my livelihood. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 15 | All | I participated in VFT meetings because I was afraid to miss the opportunity to obtain important information. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 16 | All | I participated in VFT meetings to maintain good relationships with friends, neighbors, family members, relatives, village representatives, or other villagers. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 17 | All | Before joining VFT meetings, I did not experience conflicts with other participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 18 | VFT | Through joining the facilitation training, I could get to know each other better with the other participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 19 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, I was able to build mutual trust with other participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 20 | All | The trainings for non-burning agriculture techniques (e.g. organic fertilizers, organic pesticides) strengthened relationships between VFT members (including district officers) and other participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 21 | All | VFT meetings were open to anybody who was interested in joining the discussions. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 22 | All | During VFT meetings, most participants joined the discussions actively. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 23 | All | All participants were treated equally during VFT meetings. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 24 | All | During VFT meetings, all participants’ opinions were listened to and respected by other participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 25 | All | Participants of VFT meetings made efforts to respect other participants’ opinions even if they differed from their own opinions. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 26 | All | VFT members made effots to build consensus by combining all participants’ opinions. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 27 | All | Decisions regarding the topics of VFT meetings were made when most participants attended meetings. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 28 | All | Most important decisions were made by villagers, not by VFT members. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 29 | All | There were clear rules regarding how to participate in discussions during VFT meetings. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 30 | VFT | During the facilitation training, all the participants had equal opportunities to obtain knowledge and skills. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 31 | VFT | Through the facilitation training, I could obtain abundant new knowledge and practical skills. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 32 | VFT | Through joining the facilitation training, I could obtain skills on how to combine different people’s ideas and build a consensus. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 33 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 34 | All | Trainings on non-burning agriculture techniques (e.g. organic fertilizers, organic pesticides, etc.) provided ideas regarding ways to tackle the issue of fire. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Appendix D. Questionnaire Survey Results

| No. | All/VFT 1 | Statements | Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4: Strongly agree | 3: Agree | 2: Disagree | 1: Strongly disagree | |||

| 1 | VFT | At the beginning of the facilitation training, I felt nervous because I was not confident in my knowledge and skills, compared to the other participants, particularly district government officers. | 13.8% | 65.5% | 17.2% | 3.4% |

| 2 | All | At the early stages of the VFT meetings, I felt nervous because I didn’t have enough knowledge and skills compared to the other participants, particularly district government officers. | 6.0% | 61.0% | 32.0% | 1.0% |

| 3 | All | At the early stages of the VFT meetings, I felt nervous because there were some people whom I didn’t know well, particularly the district government officers. | 14.5% | 62.0% | 22.0% | 1.5% |

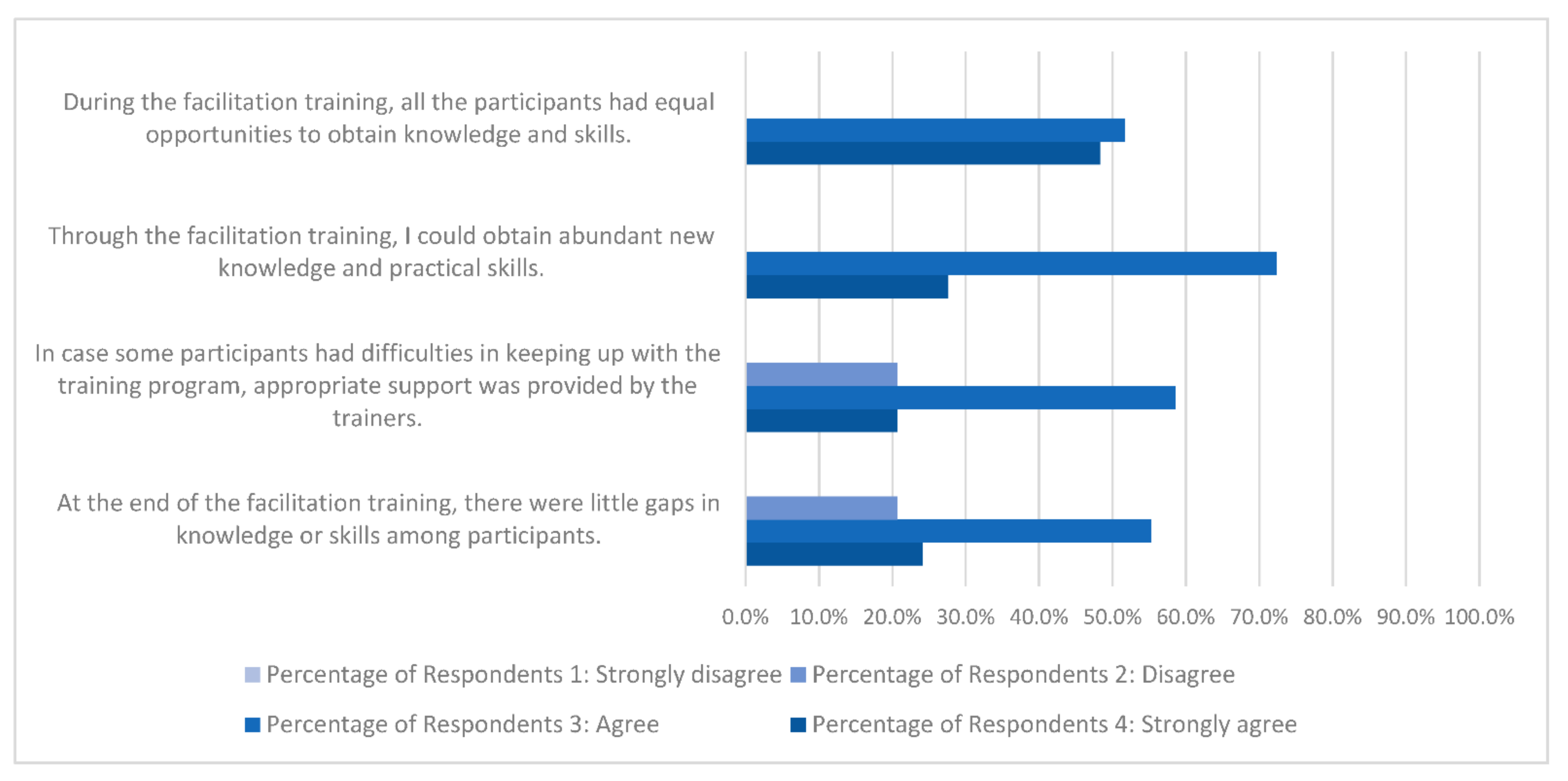

| 4 | VFT | During the facilitation training, all the participants had equal opportunities to obtain knowledge and skills. | 48.3% | 51.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 5 | VFT | Through the facilitation training, I could obtain abundant new knowledge and practical skills. | 27.6% | 72.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 6 | VFT | In case some participants had difficulties in keeping up with the training program, appropriate support was provided by the trainers. | 20.7% | 58.6% | 20.7% | 0.0% |

| 7 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 24.1% | 55.2% | 20.7% | 0.0% |

| 8 | All | During the VFT meetings, information and knowledge were equally shared with all participants. | 25.0% | 73.0% | 2.0% | 0.0% |

| 9 | All | In case some participants had difficulties in understanding the contents of the discussions, appropriate support was provided by VFT members. | 14.5% | 76.0% | 9.5% | 0.0% |

| 10 | All | I understood almost everything regarding the topics discussed during VFT meetings. | 5.0% | 59.0% | 36.0% | 0.0% |

| 11 | All | At the later stages of VFT meetings, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 3.0% | 72.0% | 24.5% | 0.5% |

| 12 | All | At the later stages of VFT meetings, I could express my opinions freely, without being nervous. | 6.5% | 72.5% | 21.0% | 0.0% |

| 13 | All | Because some village representatives facilitated the meetings as VFT members, I felt comfortable in expressing my opinions. | 6.0% | 88.5% | 5.5% | 0.0% |

| 14 | All | I participated in VFT meetings to obtain useful information or knowledge related to my livelihood. | 27.5% | 69.5% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| 15 | All | I participated in VFT meetings because I was afraid to miss the opportunity to obtain important information. | 25.0% | 62.5% | 12.5% | 0.0% |

| 16 | All | I participated in VFT meetings to maintain good relationships with friends, neighbors, family members, relatives, village representatives, or other villagers. | 36.5% | 63.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 17 | All | Before joining VFT meetings, I did not experience conflicts with other participants. | 40.0% | 59.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% |

| 18 | VFT | Through joining the facilitation training, I could get to know each other better with the other participants. | 44.8% | 55.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 19 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, I was able to build mutual trust with other participants. | 27.6% | 58.6% | 13.8% | 0.0% |

| 20 | All | The trainings for non-burning agriculture techniques (e.g. organic fertilizers, organic pesticides) strengthened relationships between VFT members (including district officers) and other participants. | 58.0% | 42.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

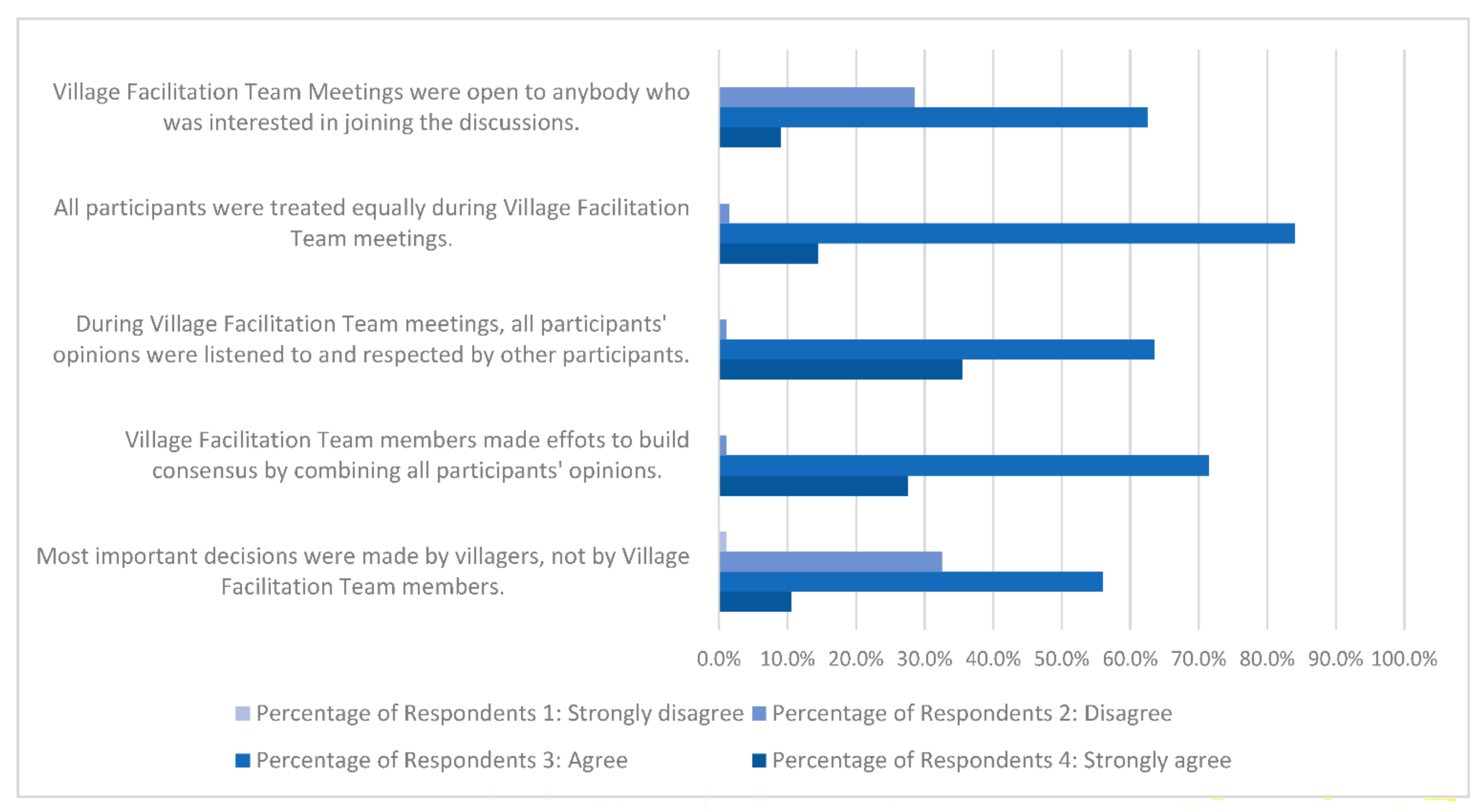

| 21 | All | VFT meetings were open to anybody who was interested in joining the discussions. | 9.0% | 62.5% | 28.5% | 0.0% |

| 22 | All | During VFT meetings, most participants joined the discussions actively. | 9.0% | 86.5% | 4.0% | 0.5% |

| 23 | All | All participants were treated equally during VFT meetings. | 14.5% | 84.0% | 1.5% | 0.0% |

| 24 | All | During VFT meetings, all participants’ opinions were listened to and respected by other participants. | 35.5% | 63.5% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| 25 | All | Participants of VFT meetings made efforts to respect other participants’ opinions even if they differed from their own opinions. | 15.0% | 72.5% | 12.5% | 0.0% |

| 26 | All | VFT members made effots to build consensus by combining all participants’ opinions. | 27.5% | 71.5% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| 27 | All | Decisions regarding the topics of VFT meetings were made when most participants attended meetings. | 20.0% | 66.0% | 14.0% | 0.0% |

| 28 | All | Most important decisions were made by villagers, not by VFT members. | 10.5% | 56.0% | 32.5% | 1.0% |

| 29 | All | There were clear rules regarding how to participate in discussions during VFT meetings. | 5.0% | 54.5% | 40.5% | 0.0% |

| 30 | VFT | During the facilitation training, all the participants had equal opportunities to obtain knowledge and skills. | 48.3% | 51.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 31 | VFT | Through the facilitation training, I could obtain abundant new knowledge and practical skills. | 27.6% | 72.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 32 | VFT | Through joining the facilitation training, I could obtain skills on how to combine different people’s ideas and build a consensus. | 20.7% | 69.0% | 10.3% | 0.0% |

| 33 | VFT | At the end of the facilitation training, there were little gaps in knowledge or skills among participants. | 24.1% | 55.2% | 20.7% | 0.0% |

| 34 | All | Trainings on non-burning agriculture techniques (e.g. organic fertilizers, organic pesticides, etc.) provided ideas regarding ways to tackle the issue of fire. | 19.0% | 71.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% |

References

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, C.; Gunarso, P.; Koesoetjahjo, I.; Wiersum, F. Governing forest landscape restoration: Cases from indonesia. Forests 2014, 5, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, C.C. Governance lessons from two sumatran integrated conservation and development projects. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: A framework for evaluating collaborative planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1999, 65, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.; Wansem, M.; Ciccarelli, A. Mediating Land Use Disputes-Pros and Cons; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Apgar, J.M.; Cohen, P.J.; Ratner, B.D.; de Silva, S.; Buisson, M.C.; Longley, C.; Bastakoti, R.C.; Mapedza, E. Identifying opportunities to improve governance of aquatic agricultural systems through participatory action research. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yaffee, S.L. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frame, T.M.; Gunton, T.I.; Day, J.C. The role of collaborative planning in environmental management: An evaluation of land and resource management planning in British Columbia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Shivakoti, G.P. (Eds.) Multi-Level Forest Governance in Asia: Concepts, Challenges and the Way Forward; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2015; p. 461. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, D.; McGee, G.J.A.; Gunton, T.I.; Day, J.C. Collaborative planning in complex stakeholder environments: An evaluation of a two-tiered collaborative planning model. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.M.; Segal, E.A.; Johnston, E.W.; Vinze, A. Understanding the influence of power and empathic perspective-taking on collaborative natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 199, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Harris, C.C. The US forest service: Whither the new resource management paradigm? J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, O. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollagher, M.; Hartz-Karp, J. The role of deliberative collaborative governance in achieving sustainable cities. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2343–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Lemos, M.C.; Huitema, D.; Hughes, T.P. Mitigation and adaptation in polycentric systems: Sources of power in the pursuit of collective goals. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattijssen, T.J.M.; Buijs, A.A.E.; Elands, B.H.M.; Arts, B.J.M.; van Dam, R.I.; Donders, J.L.M. The transformative potential of active citizenship: Understanding changes in local governance practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.W.; Jung, K. From collaborative to hegemonic water resource governance through dualism and jeong: Lessons learned from the daegu-gumi water intake source conflict in Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, D.; Maryudi, A.; Imron, M.A. Conversion of forests into oil palm plantations in west kalimantan, Indonesia: Insights from actor’s power and its dynamics. For. Pol. Econ. 2017, 78, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, J. Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbois, M.C.; Morris, M.; de Loe, R. Augmenting the IAD framework to reveal power in collaborative governance-An illustrative application to resource industry dominated processes. World Dev. 2019, 120, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbois, M.C.; de Loe, R.C. State roles and motivations in collaborative approaches to water governance: A power theory-based analysis. Geoforum 2016, 74, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, J.M. A framework for assessing power in collaborative governance processes. Public Admin. Rev. 2012, 72, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, D.S. Arguing About Consensus: Examining the Case against Western Watershed Initiatives and Other Collaborative Groups Active in Natural Resources Management; Natural Resources Law Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, C.; Banjade, M.R. Social capital, conflict, and adaptive collaborative governance: Exploring the dialectic. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.; Lovett, J.C. Prospects of public participation in the planning and management of urban green spaces in Lahore: A discourse analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Devolution of environment and resources governance: Trends and future. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodden, K. Governing sustainable coastal development: The promise and challenge of collaborative governance in Canadian coastal watersheds. Can. Geogr. 2015, 59, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Fatorelli, L.; Paavola, J.; Locatelli, B.; Pramova, E.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; May, P.H.; Brockhaus, M.; Sari, I.M.; Kusumadewi, S.D. Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Global Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensor, J.; Harvey, B. Social learning and climate change adaptation: Evidence for international development practice. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, A.; Elbers, W. Power in and over cross-sector partnerships: Actor strategies for shaping collective decisions. Admin. Sci. 2018, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.J. Who’s pulling the fracking strings? Power, collaboration and Colorado fracking policy. Environ. Pol. Govern. 2015, 25, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N. Strategies of engagement: Lessons from the critical examination of collaboration and conflict in an interorganizational domain. Organ Sci. 1998, 9, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M. Shinrin shoushitsu mondai heno shiza [Perspectives toward the issue of forest destruction]. In Ajia ni Okeru Shinrin no Shoushitsu to Hozen [Forest Destruction and Conservation in Asia]; Inoue, M., Ed.; Chuohoki: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sardjono, M.A.; Imang, N. Indonesia I: Review of local community dimensions of forest policies. In Multi-Level Forest Governance in Asia-Concepts, Challenges and the Way Forward; Inoue, M., Shivakoti, G.P., Eds.; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yonariza; Shivakoti, G.P.; Mahdi, M.T.; Yolamalinda. Indonesia III: Characteristics of forest management policy in west sumatra. In Multi-Level Forest Governance in Asia-Concepts, Challenges and the Way Forward; Inoue, M., Shivakoti, G.P., Eds.; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Laumonier, Y.; Bourgeois, R.; Pfund, J.L. Accounting for the ecological dimension in participatory research and development: Lessons learned from indonesia and madagascar. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Guernier, J.; Yasmi, Y. A fair share? Sharing the benefits and costs of collaborative forest management. Int. For. Rev. 2009, 11, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M. Komonzu no Shisou wo Motomete-Kalimantan no Mori de Kangaeru [Pursuing the Ideology of the Commons-Thoughts from the Forest in Kalimantan]; Iwanami-Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eversole, R. Remaking participation: Challenges for community development practice. Community Dev. J. 2012, 47, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JICA. Komyuniti Kyodogata Chihou Gyosei Shien Apurochi Handobukku [A Handbook for Supporting Local Governments Through Community-Based, Collaborative Approach]; Governance Taskforce, Department of Industrial Development and Public Policy, JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, T.; Robertson, P.J. Deliberation and decision in collaborative governance: A simulation of approaches to mitigate power imbalance. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 2014, 24, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M. Combining participatory processes and sustainable development goals to revitalize a rural area in Cantabria (Spain). Land 2020, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G.; Abernethy, P. Facilitating Co-Production of transdisciplinary knowledge for sustainability: Working with Canadian biosphere reserve practitioners. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherriff, S.L.; Miller, H.; Tong, A.; Williamson, A.; Muthayya, S.; Redman, S.; Bailey, S.; Eades, S.; Haynes, A. Building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research: A stakeholder interview study. Evid. Pol. 2019, 15, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partidario, M.R.; Sheate, W.R. Knowledge brokerage-potential for increased capacities and shared power in impact assessment. Environ. Impact. Assess. Rev. 2013, 39, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, V.R.; Calhoun, A.J.K.; Bell, K.P.; Johnson, T.R. Turning contention into collaboration: Engaging power, trust, and learning in collaborative networks. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.M.; Schneider, F.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Oberlack, C.; Myint, W.; Messerli, P. Whose agency counts in land use decision-making in myanmar? A comparative analysis of three cases in Tanintharyi region. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.E.; Siegert, F.; Rieley, J.O.; Boehm, H.D.V.; Jaya, A.; Limin, S. The amount of carbon released from peat and forest fires in Indonesia during 1997. Nature 2002, 420, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.E.; Rieley, J.O.; Banks, C. Global and regional importance of the tropical peatland carbon pool. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, F.; Ruecker, G.; Hinrichs, A.; Hoffmann, A.A. Increased damages from fires in logged forests during droughts caused by El Niño. Nature 2001, 414, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Shimada, S.; Ibie, B.F.; Usup, A.; Yudha, P.; Limin, S.H. Annual change of water balance and drought index in a tropical peat swamp forest of central kalimantan, indonesia. Paper presented at peatlands for People: Natural resource and functions and sustainable management. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Tropical Peatland, Jakarta, Indonesia, 22–23 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Varkkey, H. Patronage politics, plantation fires and transboundary haze. Environ. Hazards 2013, 12, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usup, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Hayasaka, H. Combustion and Thermal characteristics of peat fire in tropical peatland in central kalimantan, Indonesia. Tropics 2004, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Tanjungpura. Final Report, Fifth Year’s Baseline Surveys; Program for Community Development of Fire Control in Peatland Area: Pontianak, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, Y.; Maswadi; Oktoriana, S. Enhancing local community’s sense of ownership through international cooperation. Wetl. Res. 2017, 7, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Baldwin, C. Voice, power, and history: Ensuring social justice for all stakeholders in water decision-making. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, T.; Ashida, T. Yokuwakaru Shitsu-Teki Shakai-Chousa [Introduction to Qualitative Social Surveys]; Mineruva-Shobou: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Bowmer, K.; Syme, G.J.; Davidson, P. Assessing government intentions for australian water reform using a social justice framework. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1314–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, S.; Sakurai, Y. A study on support for dialogues in the workshop as a place for cooperative learning-focusing on intrinsic motivation. J. Arch. Plan. 2013, 78, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umans, L. Intervention, facilitation and self-development: Strategies and practices in forestry cooperation in Bolivia. Dev. Chang. 2012, 43, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H. Fasiliteita Gainen ni Kansuru Rironteki Kosatsu [A Theoretical Consideration on the Concept of Facilitation]; Bulletin of the Education Center; Faculty of Education, Utsunomiya University: Utsunomiya City, Japan, 2011; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto, Y.; Toda, Y.; Ueda, K.; Nishida, T. Giron heno sanka taido to higengo joho ni motozuku fasiliteishon no bunseki [Analyses of the facilitating behavior by using participant’s agreement and non-verbal behavior]. J. Inf. Process. 2011, 52, 3659–3670. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K. Mondai Kaiketsu Fasiliteitaa: Fasiliteishon Yousei Koza [Problem Solving Facilitator: A Training Course for Facilitation]; Toyo-Keizai Shinposha: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mikami, N. Chikyuu kibo deno shimin sanka ni okeru fasiliteitaa no yakuwari-chikyuu ondanka ni kansuru sekai shimin kaigi (WWViews) wo jirei to shite [The role of facilitators in global-scale public participation exercises: A case study on world wide views on global warming]. Jpn. J. Sci. Comm. 2010, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, T.; Hideshima, E.; Kitamura, N. Chiiki shakai no kadai kaiketsu ni muketa juumin togi purosesu ni kansuru jikkenteki bunseki [An experimental analysis for process of discussion by residents to solve regional problem]. Sociotechnica 2008, 5, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rixon, A.; Smith, T.F.; McKenzie, B.; Sample, R.; Scott, P.; Burn, S. Perspectives on the art of facilitation: A Delphi study of natural resource management facilitators. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, T.I.; Day, J.C. The theory and practice of collaborative planning in resource and environmental management. Environments 2003, 31, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, H.; Yuzawa, A. Waaku shoppu ni okeru goi keisei purosesu no hyouka [An evaluation of consensus making in workshop]. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2001, 10, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, C. Power, responsibility and justice: A review of local stakeholder participation in European flood risk management. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubouchi, A. Naze PLA nanoka- kaihatsu ni okeru paradaimu tenkan no hitsuyosei, zoku nyuumon shakai kaihatsu- pla: Juumin shutai no gakushuu to kodo niyoru kaihatsu [why pla? the need for a paradigm shift in development. In Introduction to Social Development-PLA: Development Through Community-Based Learning and Action]; Project, P.L.A., Ed.; International Development Journal Ltd: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 202–217. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, M.J.; Coleman, K.J. The multidimensionality of trust: Applications in collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Qi, H.T. The entangled twins: Power and trust in collaborative governance. Admin. Soc. 2019, 51, 607–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, R.A.; Langston, J.D.; Margules, C.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Lim, H.S.; Sari, D.A.; Sururi, Y.; Sayer, J. Governance challenges in an eastern indonesian forest landscape. Sustainability 2018, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arai, Y.; Maswadi; Oktoriana, S.; Suharyani, A.; Didik; Inoue, M. How Can We Mitigate Power Imbalances in Collaborative Environmental Governance? Examining the Role of the Village Facilitation Team Approach Observed in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073972

Arai Y, Maswadi, Oktoriana S, Suharyani A, Didik, Inoue M. How Can We Mitigate Power Imbalances in Collaborative Environmental Governance? Examining the Role of the Village Facilitation Team Approach Observed in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073972

Chicago/Turabian StyleArai, Yuki, Maswadi, Shenny Oktoriana, Anita Suharyani, Didik, and Makoto Inoue. 2021. "How Can We Mitigate Power Imbalances in Collaborative Environmental Governance? Examining the Role of the Village Facilitation Team Approach Observed in West Kalimantan, Indonesia" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073972

APA StyleArai, Y., Maswadi, Oktoriana, S., Suharyani, A., Didik, & Inoue, M. (2021). How Can We Mitigate Power Imbalances in Collaborative Environmental Governance? Examining the Role of the Village Facilitation Team Approach Observed in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(7), 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073972