The Role of Online Brand Community Engagement on the Consumer–Brand Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

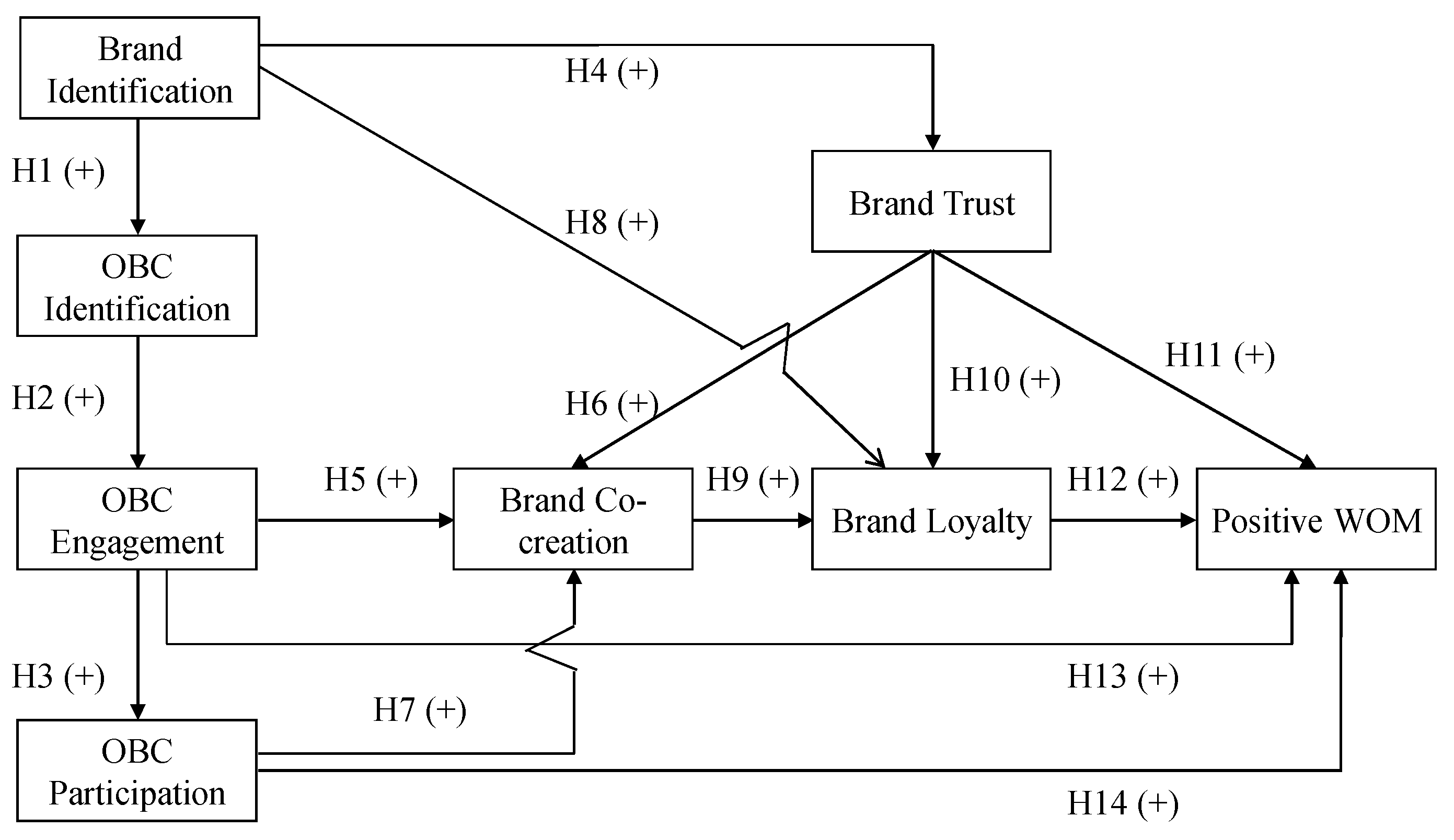

- Developing an integrated model able to explain and predict how engagement and participation in OBC develop leading to support of the brand beyond customer loyalty.

- Defining the role of variables, such as identification and trust, in the way that OBC-engaged users develop loyalty, participate in value co-creation, and deliver positive WOM.

2. Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Identification with the Community

2.2. Engagement with the Community

2.3. Participation in the Community

2.4. Trust in the Brand

2.5. Consumer Willingness to Co-Create with the Brand

2.6. Brand Loyalty

2.7. Positive WOM

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Questionnaire

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

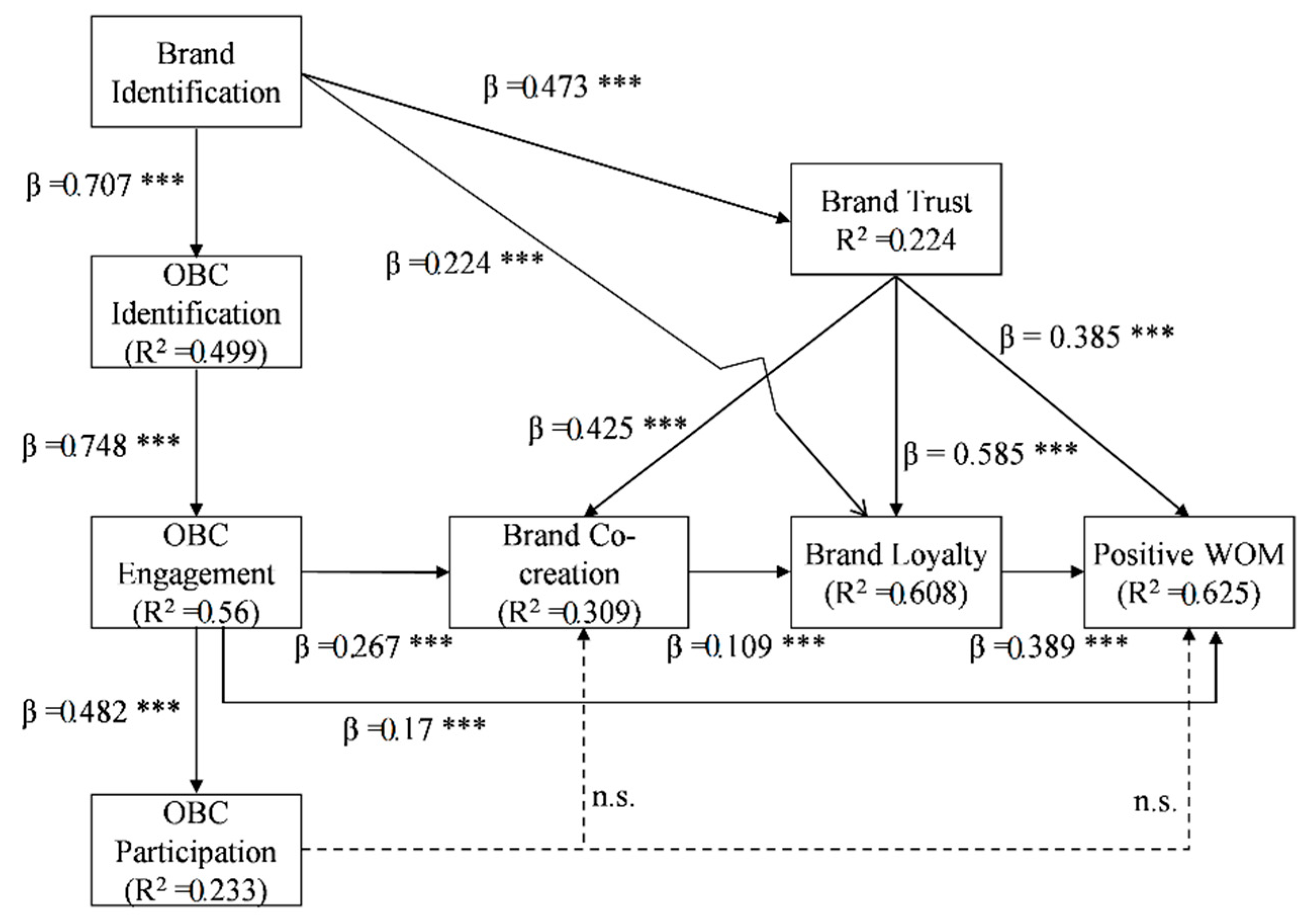

4.2. Structural Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coelho, P.S.; Rita, P.; Santos, Z.R. On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Nayak, J.K. Understanding the participation of passive members in online brand communities through the lens of psychological ownership theory. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrout, H.; Nagy, G. Trust and commitment within a virtual brand community: The mediating role of brand relationship quality. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 939–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Richard, M.-O.; Sankaranarayanan, R. The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.; Peres, F. Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, R.; Lee, M.; Chen, J. When will consumers be ready? A psychological perspective on consumer engagement in social media brand communities. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busalim, A.H.; Hussin, A.R.C.; Iahad, N.A. Factors influencing customer engagement in social commerce websites: A systematic literature review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, F.; Saumya, S. Virtual communication and consumer-brand relationship on social networking sites–Uses & gratifications theory perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liao, J.; Zheng, S.; Li, B. Examining Drivers of Brand Community Engagement: The Moderation of Product, Brand and Consumer Characteristics. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, V. Drivers of brand community engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketing Science Institute (MSI). 2010–2012 Research Priorities; Marketing Science Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marketing Science Institute (MSI). 2018–2020 Research Priorities; Marketing Science Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L.D. The role of brand community identification and reward on consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty in virtual brand communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Brexendorf, T.O.; Fassnacht, M. The impact of external social and internal personal forces on consumers’ brand community engagement on Facebook. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Tsai, K.-M. An Empirical Study of Brand Fan Page Engagement Behaviors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Molinillo, S.; Aguilar-Illescas, R.; Esteban-Millat, I. Consumer engagement in online brand community. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2017, 23, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M.-O. Testing an extended model of consumer behavior in the context of social media-based brand communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Wang, K.-Y.; Chang, S.-H.; Lin, J.-A. Investigating the development of brand loyalty in brand communities from a positive psychology perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.J.; Badrinarayanan, V.A.; Taute, H.A. Explaining behavior in brand communities: A sequential model of attachment, tribalism, and self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-W.; Wang, Y.-B. Re-purchase intentions and virtual customer relationships on social media brand community. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, W.W.C.; Chou, C.Y.; Chen, T. Working consumers’ psychological states in firm-hosted virtual communities. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hsiao, S.-H.; Yang, Z.; Hajli, N. The impact of sellers’ social influence on the co-creation of innovation with customers and brand awareness in online communities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L. Social media engagement: A model of antecedents and relational outcomes. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.; Bagozzi, R.; Pearo, L. A social influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network and Small Group Based Virtual Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European Car Clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiray, M.; Burnaz, S. Exploring the impact of brand community identification on Facebook: Firm-directed and self-directed drivers. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Kim, Y.-K. Single-brand retailers: Building brand loyalty in the off-line environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Piven, I.; Breazeale, M. Conceptualizing the brand in social media community: The five sources model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuskej, U.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K. The role of consumer-brand identification in building brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 66, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.D.; Suter, T.A.; Brown, T.J. Social versus psychological brand community the role of psychological sense of brand community. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-H.; Choi, S.M. MINI-lovers, maxi-mouths: An investigation of antecedents to eWOM intention among brand community members. J. Mark. Commun. 2011, 17, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Su, C.; Zhou, N. How do brand communities generate brand relationships? Intermediate mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Butt, O.J.; Wei, J. My identity is my membership: A longitudinal explanation of online brand community members’ behavioral characteristics. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 19, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lee, M.K.O.; Liu, R.; Chen, J. Trust transfer in social media brand communities: The role of consumer engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M.-O. The roles of brand community and community engagement in building brand trust on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, E.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y.; Huang, H.-C. Fairness and devotion go far: Integrating online justice and value co-creation in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, A.M.; Schau, H.J. Religiosity in the abandoned Apple Newton brand community. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, M.; Hu, N.; Wang, Y. How community interactions contribute to harmonious community relationships and consumers’ identification in online brand community. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonteri, L.; Kosonen, M.; Ellonen, H.K.; Tarkiainen, A. Antecedents of an experienced sense of virtual community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Duclou, M. Health and fitness online communities and product behavior. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinen, S. Understanding user participation in online communities: A systematic literature review of empirical studies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Den Ambtman, A.; Bloemer, J.; Horváth, C.; Ramaseshan, B.; Van De Klundert, J.; Canli, Z.G.; Kandampully, J. Managing brands and customer engagement in online brand communities. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relling, M.; Schnittka, O.; Sattler, H.; Johnen, M. Each can help or hurt: Negative and positive word of mouth in social network brand communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 33, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N. Cultivating trust and harvesting value in virtual communities. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Goode, M.M.H. The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Harris, L. Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocchi, G.; Morandin, G.; Bergami, M. Brand communities: Loyal to the community or to the brand? Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.; Smith, S. Cocreation is chaotic: What it means for marketing when no one has control. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 39, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwass, V. Co-creation: Toward a taxonomy and an integrated research perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2010, 15, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M.; Arnould, E.J. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Mydock, S.; Pervan, S.J.; Kortt, M. Facebook, self-disclosure, and brand-mediated intimacy: Identifying value creating behaviors. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J.; Jawecki, G.; Mühlbacher, H. Innovation creation by online basketball communities. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C.M. Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships and social media. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating value through customers’ experiences: The Nike case. Strategy Leadersh. 2008, 36, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Schnebelen, S.; Schäfer, D. Antecedents and consequences of the quality of e-customer-to-customer interactions in B2B brand communities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, A.V.; Murphy, P.E. Marketing with integrity: Ethics and the service-dominant logic for marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Sarmah, B.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of Stimulus-Organism-Response. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, P.; Watt, J.H. Managing customer experiences in online product communities. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Relationship quality, community promotion and brand loyalty in virtual communities: Evidence from free software communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kankanhalli, A.; Kim, S.H. Which idea are more likely to be implemented in online user innovation communities? An empirical analysis. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 84, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.W.; Giese, J.L.; Johnson, J.L. Customer retailer loyalty in the context of multiple channel strategies. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Yieh, K. Predicting smartphone brand loyalty: Consumer value and consumer-brand identification perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. Brand passion: Antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 66, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P.; Knox, S. Co-creating brands: Diagnosing and designing the relationship experience. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.L.; Hua, Z. The deeper, the better? Effect of online brand community activity on customer purchase frequency. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossío-Silva, F.-J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.-A.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Value co-creation and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer trust, value and loyalty in relational exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M. The different roles of satisfaction, trust and commitment for relational and transactional consumers. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Influence of consumer attitude toward online brand community on revisit intention and brand trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Kamboj, S.; Kumar, V.; Rahman, Z. Examining consumer brand relationships on social media platforms. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Broderick, A.J.; Lee, N. Word of Mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Y.; Ting, I.H.; Wu, H.J. Discovering interest groups for marketing in virtual communities: An integrated approach. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1360–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, O.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Self-presentation, privacy and electronic word-of-mouth in social media. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijoria, C.; Mukherjee, S.; Datta, B. Impact of the antecedents of eWOM on CBBE. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. The role of satisfaction and website usability in developing customer loyalty and positive word-of-mouth in the e-banking services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 26, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukeboom, C.J.; Kerkhof, P.; De Vries, M. Does a Virtual Like Case actual liking? How following a Brand’s Facebook updates enhances brand evaluations and purchase intention. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 32, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Knoll, K.; Leidner, D.E. Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1998, 14, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Aguilar-Illescas, R.; Molinillo, S.; Martínez-López, F.J. Trust and loyalty in online brand communities. Span. J. Mark. Esic 2020, 24, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Kim, Y.G. Knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An e-business perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 2004, 26, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, A.M.; Schau, H.J. How to inspire value-laden collaborative consumer-generated content. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, X.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.H. Social shopping website quality attributes increasing consumer participation, positive eWOM, and co-shopping: The reciprocating role of participation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Determinants of the intention to participate in firm-hosted online travel communities and effects on consumer behavioral intentions. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Sousa, C.M.P. Structural Equation Modelling in Marketing and Business Research: Critical Issues and Practical Recommendations. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 115–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Wolfinbarger, M.; Bush, R.; Ortinau, D. Essentials of Marketing Research; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nurosis, M.J. SPSS Statistical Data Analysis; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M.; Van Trijp, H.C.M. The use of LISREL in validating marketing constructs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1991, 8, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raies, K.; Mühlbacher, H.; Gavard-Perret, M.L. Consumption community commitment: Newbies’ and longstanding members’ brand engagement and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediatting effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 310 | 49.4 |

| Female | 318 | 50.6 |

| Age | ||

| ≤20 | 298 | 47.5 |

| 21–30 | 320 | 50.9 |

| ≥31 | 10 | 1.6 |

| Net annual household income (€) | ||

| <1200 | 251 | 40 |

| 1201–1800 | 161 | 25.5 |

| 1801–3000 | 119 | 19 |

| 3001–5000 | 64 | 10.2 |

| >5000 | 33 | 5.3 |

| Community membership sector | ||

| Food and beverages | 35 | 5.6 |

| Culture | 17 | 2.7 |

| Sport | 112 | 17.8 |

| Retail | 35 | 5.6 |

| Electronics | 55 | 8.8 |

| Fashion and shoes | 170 | 27.1 |

| Motor | 24 | 3.8 |

| Leisure | 68 | 10.8 |

| Tourism and hospitality | 24 | 3.8 |

| Other | 88 | 14 |

| Construct and Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Brand identification (CA: 0.837; CR: 0.841; AVE: 0.639) | |

| This brand says a lot about the kind of person I am. | 0.825 |

| This brand’s image and my self-image are similar in many respects. | 0.814 |

| This brand plays an important role in my life. | 0.758 |

| OBC identification (CA: 0.838; CR: 0.798; AVE: 0.570) | |

| The friendships I have with other brand community members mean a lot to me. | 0.707 |

| If brand community members planned something, I’d think of it as something “we” would do rather than something “they” would do. | 0.717 |

| I see myself as a part of the brand community. | 0.835 |

| OBC engagement (CA: 0.805; CR: 0.857; AVE: 0.599) | |

| I benefit from following the community’s rules. | 0.764 |

| I am motivated to participate in the activities because I feel good afterwards or because I like it. | 0.789 |

| I am motivated to participate in the community’s activities because I am able to support other members. | 0.782 |

| I am motivated to participate in the community’s activities because I am able to reach personal goals. | 0.761 |

| OBC participation | |

| How often did you participate in activities of your online brand community within the last ten weeks? 1: I haven’t participated at all; 7: Very often. | |

| Willingness to co-create with the brand (CA: 0.968; CR: 0.970; AVE: 0.890) | |

| I am willing to work with this brand to design new products. | 0.921 |

| I am willing to co-develop products/services with this brand. | 0.955 |

| I am willing to co-design products/services with this brand. | 0.956 |

| Overall, I am willing to cooperate with this brand in developing new products/services. | 0.941 |

| Brand loyalty (CA: 0.893; CR: 0.896; AVE: 0.742) | |

| I intend to buy this brand in the near future. | 0.877 |

| I would actively search for this brand in order to buy it. | 0.896 |

| I intend to buy other products of this brand. | 0.809 |

| Brand trust (CA: 0.835; CR: 0.842; AVE: 0.641) | |

| My brand gives me everything that I expect out of the product. | 0.769 |

| I rely on my brand. | 0.871 |

| My brand never disappoints me. | 0.757 |

| Positive WOM (CA: 0.900; CR: 0.904; AVE: 0.760) | |

| I am going to spread positive WOM about the brand. | 0.903 |

| I will recommend this brand to other customers. | 0.896 |

| I will point out the positive aspects of this brand if anybody criticizes it. | 0.813 |

| BI | OBCI | OBCE | BCC | BT | BL | PWOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 0.799 | ||||||

| OBCI | (0.609–0.741) 0.675 | 0.755 | |||||

| OBCE | (0.476–0.624) 0.55 | (0.678–0.802) 0.74 | 0.774 | ||||

| BCC | (0.377–0.521) 0.449 | (0.235–0.403) 0.319 | (0.294–0.45) 0.372 | 0.94 | |||

| BT | (0.409–0.561) 0.485 | (0.217–0.401) 0.309 | (0.249–0.425) 0.337 | (0.445–0.577) 0.511 | 0.800 | ||

| BL | (0.458–0.598) 0.528 | (0.216–0.392) 0.304 | (0.278–0.446) 0.362 | (0.475–0.599) 0.537 | (0.68–0.78) 0.73 | 0.861 | |

| PWOM | (0.4–0.548) 0.474 | (0.457–0.429) 0.343 | (0.336–0.496) 0.416 | (0.407–0.539) 0.473 | (0.71–0.80) 0.759 | (0.699–0.787) 0.743 | 0.872 |

| OBCP | (0.347–0.607) 0.31 | (0.416–0.688) 0.359 | (0.646–0.902) 0.503 | (0.159–0.407) 0.28 | (0.134–0.398) 0.173 | (0.169–0.425) 0.193 | (0.251–0.503) 0.245 |

| MSV | 0.455 | 0.547 | 0.547 | 0.288 | 0.576 | 0.552 | 0.576 |

| ASV | 0.256 | 0.219 | 0.237 | 0.184 | 0.263 | 0.273 | 0.097 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-López, F.J.; Aguilar-Illescas, R.; Molinillo, S.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Esteban-Millat, I. The Role of Online Brand Community Engagement on the Consumer–Brand Relationship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073679

Martínez-López FJ, Aguilar-Illescas R, Molinillo S, Anaya-Sánchez R, Coca-Stefaniak JA, Esteban-Millat I. The Role of Online Brand Community Engagement on the Consumer–Brand Relationship. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073679

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-López, Francisco J., Rocío Aguilar-Illescas, Sebastián Molinillo, Rafael Anaya-Sánchez, J. Andres Coca-Stefaniak, and Irene Esteban-Millat. 2021. "The Role of Online Brand Community Engagement on the Consumer–Brand Relationship" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073679

APA StyleMartínez-López, F. J., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., & Esteban-Millat, I. (2021). The Role of Online Brand Community Engagement on the Consumer–Brand Relationship. Sustainability, 13(7), 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073679