Food Waste in Households in Poland—Attitudes of Young and Older Consumers towards the Phenomenon of Food Waste as Demonstrated by Students and Lecturers of PULS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

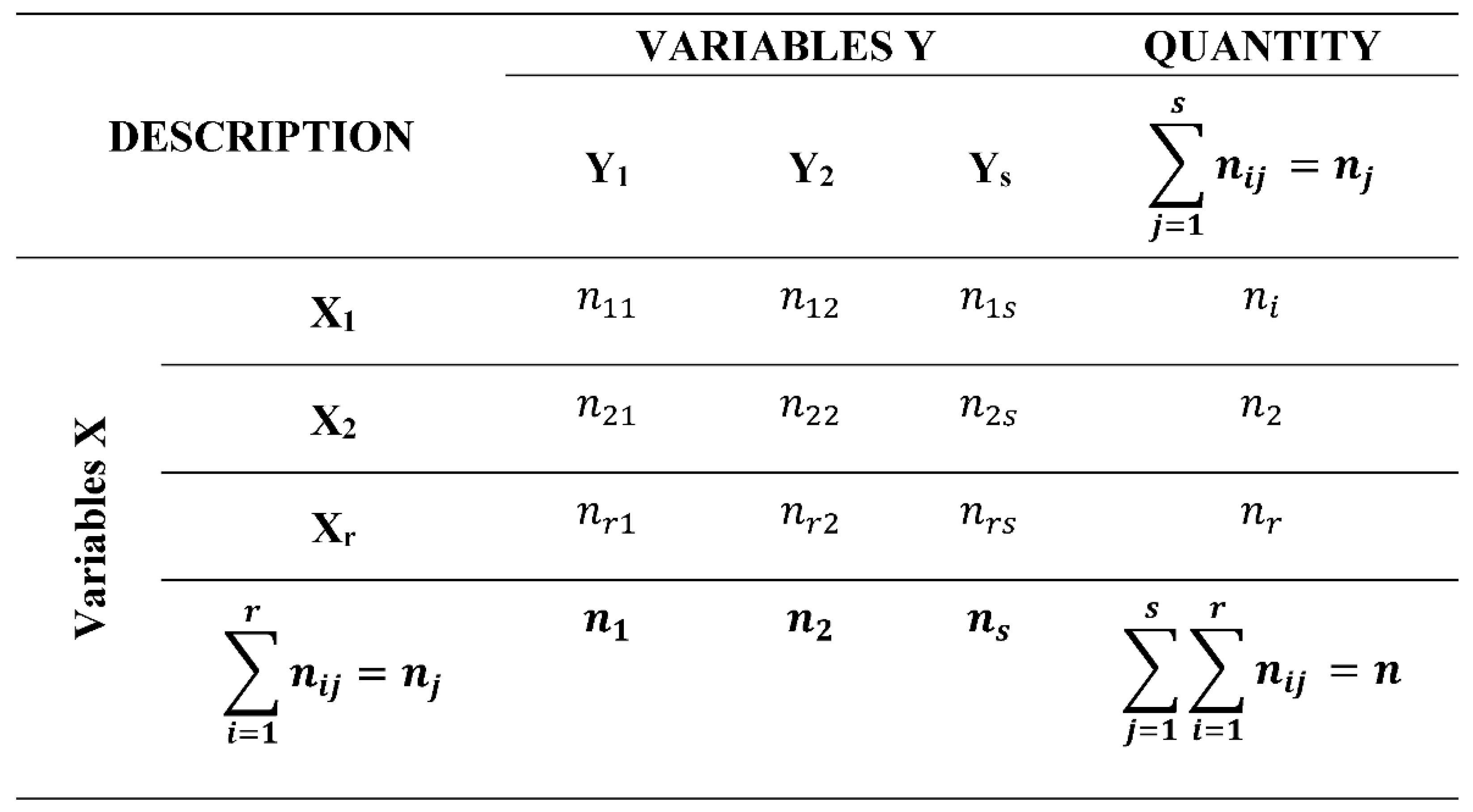

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Surveyed Population of Respondents

4.2. Behaviour Related to Food Purchasing and Estimation of Food Expenditures in Households

4.3. Food Waste in Households

4.4. Causes of Food Waste in Households

4.5. The Effects of Household Food Waste and Recommendations for the Future (Noticing the Food Waste Problem and Its Consequences)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Proper food storage, appropriate use of food surplus, awareness of both the consequences of food waste and the existence of this problem is a consumer behavior that has a significant effect on the magnitude of food waste in households. Respecting of appropriate rules and an increase in consumer and public awareness can help reduce food waste.

- Food waste was observed in both types of analyzed households, however, based on the conducted research, it can be concluded that students waste food more frequently and in larger quantities than PULS employees. This situation is related to different consumer habits and attitudes towards food waste. Students are more likely to have an emotional approach to shopping (cravings) and they purchase food products without any pre-prepared shopping list. Moreover, they often live alone or with friends and prepare meals just for themselves. This lifestyle may result in lower food expenditures; however, it also contributes to greater food waste (lack of ideas for the use of leftovers, a belief that food prices are low).

- The research results indicate that employees are effective in reducing food waste in their own households through better use of leftovers (e.g., by making homemade preserves or preparing more meals). Besides, some older employees are likely to have eating habits that derive from the period of the controlled economy when food distribution was limited and consumers were more resourceful in preparing meals (use of whole food products and aversion to food waste).

- Poland, as an economically developed country and a member of the EU, implements development goals, including sustainable consumption and production (SCP). On the one hand, there is an overproduction of food and its waste, however, the problem of malnutrition in the world is growing. Recent forecasts predicted a decline in the number of malnourished people worldwide, but this was changed by the Covid-19 pandemic. As Reiss-Andersen, the president of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, emphasized, announcing the World Food Program (WFP) as the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize Winner, “The coronavirus pandemic has caused more people to starve. The situation worsens […], the combination of disease and hunger is particularly dangerous” [28].

- Food waste also contributes to environmental pollution, degradation, and depletion of natural resources, threatening food safety. Therefore, halving the problem of food waste by 2030 is one of the 17 development goals of the United Nations. The European Union is trying to prevent food waste and reduce it by increasing the knowledge and awareness of consumers, various types of educational campaigns, and the correct redistribution of food and measurement of waste in EU countries. Due to the EU’s obligation to reduce food losses and food waste by 50% by 2030, as well as to report the losses incurred, it is necessary to know the starting situation [28].

- The research carried out and described in the article may contribute to making consumers aware of the essence of the problem of food waste, which may result in Polish households, based on participation in social campaigns organized, among others, by Poznań University of Life Sciences, having more knowledge in the field of rational waste management and undertaking activities in the field of purchasing planning and applying the “zero waste” principle.

- -

- produce less waste,

- -

- reuse items that are suitable for this,

- -

- give to others instead of throwing away,

- -

- use resources, water, and electricity more wisely, so as not to waste them,

- -

- buy locally,

- -

- change the means of transport to a more ecological one,

- -

- experience and not just consume [69].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonnensson, U. Global Food Losses and Food Waste. In Proceedings of the Save Food Congress, Düseldorf, Germany, 16–17 May 2011; Available online: https://www.madr.ro/docs/ind-alimentara/risipa_alimentara/presentation_food_waste.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Papargyropoulu, E.; Lozano, R.; Steiinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The Food Waste Hierarchy as a Framework for the Management of Food Surplus and Food Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enos, A.K. Assessing the Socio-Economic Impact of Food Waste among International Students. Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences Institute of Regional Economics and Rural Development, 2019, Szent István University in Gödöllő, Hungary. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332353148_ASSESSING_THE_SOCIO-ECONOMIC_IMPACT_OF_FOOD_WASTE_AMONG_INTERNATIONAL_STUDENTS (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Murawska, A. Marnowanie żywności wspólny problem (Food Waste a Common Problem). Portal Informacyjny Uniwersytetu Technologiczno-Przyrodniczego im. Jana i Jędrzeja Śniadeckiego w Bydgoszczy, Bydgoszcz, Poland. 2019. Available online: https://www.utp.edu.pl/pl/portal/strefa-popularnonaukowa/1762-marnowanie-zywnosci-wspolny-problem (accessed on 21 November 2020). (In Polish).

- Śmiechowska, M. Zrównoważona konsumpcja a marnotrawstwo żywności (Sustainable Food Consumption and Food Wasting). Ann. Acad. Med. Gedan. 2015, 45, 89–97. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste. Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Verghese, K.; Lewis, H.; Loskrey, S.; Williams, H. Packaging’s Role in Minimizing Food Loss and Waste Across the Supply Chain. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food Waste within Food Supply Chains: Quantification and Potential for Change to 2050. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFCO SYSTEM. Stopping Food Waste and Food Loss. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifco.com/pl/stopping-food-waste-and-food-loss/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Czarniawska, B.; Löfgren, O. Coping with Excess. How Organizations, Communities and Individuals Manage Overflows, 1st ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 217–236. ISBN 978-1782548577. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3901e.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture. Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109551-5. ISSN 2522-722X. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6583e.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- OECD/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2015–2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2015-en (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Smil, V. Improving Efficiency and Reducing Waste in Our Food System. Environ. Sci. 2004, 1, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, R.J.; Buzby, J.C.; Bennett, B. Postharvest losses and waste in developed and less developed countries: Opportunities to improve resource use. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 149, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; De Moel, H.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O.; Ward, P.J. Lost food, wasted resources: Global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, A.; James, K. Accounting for the Impact of Food Waste on Water Resources and Climate Change. In Food Industry Wastes. Assessment and Recuperation of Commodities, 1st ed.; Kosseva, M.R., Webb, C., Eds.; Elsvier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 217–236. ISBN 978-0-12-391921-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Wstege Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/food-wastage-footprint-impacts-natural-resources (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Okazaki, W.K.; Turn, S.Q.; Flachsbart, P.G. Characterization of Food Waste Generators: A Hawaii Case Study. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the Word, Safe Guarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition/en/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- WRAP. Household Food and Drink Waste in the UK; Final Report; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2012; ISBN 1-84405-430-6. Available online: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Household_food_and_drink_waste_in_the_UK_-_report.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Bräutigam, K.-R.; Jörissen, J.; Preifer, C. The Extent of Food Waste Generation Across EU-27: Different Calcultion Methods and the Reliability of Their Results. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Giménez, A.; Grønhøj, A.; Ares, G. Avoiding Household Food Waste, One Step at a Time: The Role of self-efficacy, convenience orientation, and the good provider identity in distinct situational contexts. JCA 2019, 54, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Grzesińska, W.; Tomaszewska, M.; Rudziński, M. Marnotrawstwo żywności jako przykład nieefektywnego zarządzania w gospodarstwach domowych (Food Waste as an Example Inefficient Management in Households). Roczniki Naukowe Stowarzyszenia Ekonomistów Rolnictwa i Agrobiznesu 2015, 17, 39–43. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Ktajewska, D. Analysis of the Behaviours of Polish Consumers in Relation to Food Waste. Sustainblity 2020, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarczyk, B.; Machowska, E. Food Waste in the World and in Poland. АКАДЕМІЧНИЙ ОГЛЯД 2019, 1, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Behaviour. Two Routes to Food Waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łaba, S.; Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Łaba, R.; Szczepański, K.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A.; Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Próba oszacowania strat i marnotrawstwa żywności w Polsce (An Attempt to Estimate Food Loss and Waste in Poland). Przem. Spoż. 2019, 74, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUSIONS. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels. Reducing Food Waste through Social Innovations. 2016. Available online: http://www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20levels.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- WRAP. Food Surpluses and Waste in the UK Key Facts; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2020; p. 16. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food-surplus-and-waste-in-the-UK-key-facts-Jan-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Food Loss and Waste. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/food-loss-and-waste (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Monier, V.; Mudgal, S.; Escalon, V.; O’Connor, C.; Gibon, T.; Anderson, G.; Montoux, H. Final Report—Preparatory Study on FoodWaste AcrossEU27; European Commission BIO Intelligence Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2017).

- Koivupuro, H.-K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW-EPA. Food Waste Avoidance Benchmark Study, State of New South Wales (NSW) Environment Protection Authority(EPA), September 2012, Australia. Available online: http://www.frankston.vic.gov.au/files/34d7963e-24ab-455b-a1f5-a22300d89be2/Love_food_hate_waste.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Yannakoulia, M.; Mamalaki, E.; Anastasiou, C.A.; Mourtzi, N.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Scarmeas, N. Eating habits and behaviors of older people: Where are we now and where should we go? Maturitas 2018, 114, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Demographic and Labor Market Research: Statistics Poland. Population projection for 2014–2050. Statistical Publishing Department, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/population/population-projection/population-projection-2014-2050,2,5.html (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Kaniewska-Sęba, A. Polscy seniorzy wyzwanie dla marketingu w XXI wieku (Polish Seniors a Challenge for Marketing in the XXI Century). Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polit. 2016, 4, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tańska, M.; Babicz-Zielińska, E.; Przysławski, J. Attitudes of the elderly towards the issues of health and healthy food. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2013, 94, 915–918. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M. Zachowania żywieniowe Konsumentów a Proces Edukacji Żywieniowej (Nutritional Behaviour of Consumers and the Process of Nutritional Education); Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food Waste Generation at Household Level: Results of a Survey among Employees of Two European Research Centers in Italy and Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2695–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuła, K. Elementy Statystyki w Zadaniach (Elements of Statistics in Tasks), 2nd ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2003; ISBN 978-83-01-16774-5. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bilali, H.E.; Abouabdillah ACapone RYoussfi, L.E.; Debs, P.; Harraq, A.; Amrani, M.; Bottalico, F.; Driouech, N. Household Food Waste in Morocco: An Exploratory Survey. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Scientific Agricultural Symposium “Agrosym 2015”, Jahorina, Bosnia, 15–18 October 2015; pp. 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti Soup: The Complex World of Food Waste Behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki Żywności Raport Nie Marnuj Jedzenia 2017. Wyniki Badania CAPIbus dla Federacji Polskich Banków Żywności). Available online: https://bzsos.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Nie-marnuj-jedzenia_2017.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2021). (In Polish).

- Rejman, K.; Wrońska, J. Marnotrawstwo żywności w gospodarstwach domowych w kontekście rozwoju sfery konsumpcji (Food Waste in Households in the Context of the Development of the Consumption Sphere). In Rolnictwo, Gospodarka Żywnościowa, Obszary Wiejskie 10 lat w Unii Europejskiej (Agriculture, Food Economy, Rural Areas 10 Years in the European Union), 1st ed.; Drejerska, N., Ed.; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 97–110. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food Waste Paradox: Antecedents of Food Disposal in Low Income Households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding Food Waste by Romanian Consumers: The Importance of Planning and Shopping Routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out Food Waste Behaviour: A Survey on the Motivators and Barriers of Self-reported Amounts of Food Waste in Households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H.S.; Aramyan, L.H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of Household Food Waste Behavior in Tehran City: A Structural Model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilali, H.E.; Yildirim, H.; Capone, R.; Karanlik, A.; Bottalico, F.; Debs, P. Food Wastage in Turkey: An Exploratory Survey on Household Food Waste. JFNR 2016, 4, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki Żywności. Marnując żywność, marnujesz planetę. Raport Federacji Polskich Banków Żywności. Nie Marnuję Jedzenia 2018. Available online: https://bankizywnosci.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Przewodnik-do-Raportu_FPBZ_-Nie-marnuj-jedzenia-2018.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2021). (In Polish).

- Banki Żywności Raport FPBŻ Marnowanie żywności w Polsce i Europie 2012. Nie Marnuj Jedzenia. Available online: http://www.niemarnuje.pl/files/sdz_2012_10_16_raport_marnowanie_fpbz.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2021). (In Polish).

- Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Hartikainen, H.; Jalkanen, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food Waste Volume and Composition in Finnish Households. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H.J. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household Food Waste Behaviour in EU-27 Countries: A Multilevel Analysis. Food Policy 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki Żywności. Raport Federacji Polskich Banków Żywności. Zapobieganie Marnowaniu Żywności z Korzyścią dla Społeczeństwa, Dobroczynność bez VAT. 2013. Available online: https://www.food-law.pl/files/raport-zapobieganie-marnowania-zywnosci.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2021). (In Polish).

- Banki Żywności. Raport Federacji Polskich Banków Żywności Nie Marnuj Jedzenia 2015. Marnowanie Jedzenia to Śmierdząca Sprawa. Available online: https://suwalki.bankizywnosci.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/raport_niemarnuj_jedzenia_2015.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021). (In Polish).

- Zabłocka, K.; Rejman, K.; Prandota, A. Marnotrawstwo Żywności w kontekście racjonalnego gospodarowania nią w gospodarstwach domowych polskich i szwedzkich studentów (Food Waste in the Context of Rational Management in Households of Polish and Swedish students). Zeszyty Naukowe Szkoły Głównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego. Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2016, 114, 19–32. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, A.; Janoś-Kresło, M. Marnowanie żywności jako problem społeczny (Food Waste as a Social Problem). Handel Wewn. 2013, 4, 14–25. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Flash Eurobarometer 425 ‘Food Waste and Date Marking’, Fieldwork; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, September 2015; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/pl/data/dataset/S2095_425_ENG (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Tomaszewska, M.; Bilska, B.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Piecek, M. Analiza przyczyn marnowania żywności w polskich gospodarstwach domowych (Analysis of the causes of food waste (In Polish) households). In Straty i Problemy Marnowania Żywności w Polsce. Skala i Przyczyny Problemu (Food Losses and Problems in Poland. Scale and Causes of Problems), 1st ed.; Łaba, S., Ed.; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 132. ISBN 978-83-60312-68-1. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Understanding Food Waste. In Key Findings of our Recent Research on the Nature, Scale and Causes of Household Food Waste; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2007; p. 28. ISBN 1-84405-310-5. Available online: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/FoodWasteResearchSummaryFINALADP29_3__07.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- WRAP. The Food We Waste, Food Waste Report V2; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2008; p. 237. ISBN 1-84405-383-0. Available online: https://www.lefigaro.fr/assets/pdf/Etude%20gaspillage%20alimentaire%20UK2008.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Janssens, K.; Lambrechts, W.; van Osch, A.; Semeijn, J. How Consumer Behavior in Daily Food Provisioning Affects Food Waste at Household Level in The Netherlands. Foods 2019, 8, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.A.; Ferrari, G.; Secondi, L.; Principato, L. From the Table to Waste: An Exploratory Study on Behavior Towards Food Waste of Spanish and Italian Youths. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Res. Con. Rec. 2020, 153, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Waste 2021. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/events/4204430559571782/?active_tab=discussion (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- COMMISSION DELEGATED DECISION (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 Supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards a Common Methodology and Minimum Quality Requirements for the Uniform Measurement of Levels of Food Waste. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019D1597&from=en (accessed on 12 March 2021).

| Characteristics of the Respondents | Description | Students N1 = 187 | Employees N2 = 79 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 72.7 | 69.6 |

| Male | 27.3 | 30.4 | |

| Age | 19–26 years | 100.0 | 3.8 |

| 27–35 years | 0.0 | 24.1 | |

| 36–50 years | 0.0 | 46.8 | |

| more than 50 years | 0.0 | 25.3 | |

| Place of residence | Village | 26.2 | 20.3 |

| City up to 10,000 residents | 10.2 | 2.5 | |

| City from 10,000 up to 50,000 residents | 19.8 | 6.3 | |

| City from 50,000 up to 100,000 residents | 7.0 | 6.3 | |

| City from 100,000 up to 500,000 residents | 10.7 | 7.6 | |

| City over 500,000 residents | 26.2 | 57.0 | |

| Education | Basic | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Medium | 69.0 | 3.8 | |

| Higher (1st degree) | 30.5 | 2.5 | |

| Higher (2nd degree) | 0.5 | 27.8 | |

| Higher (3rd degree) | 0.0 | 65.8 | |

| Professional status | Student | 98.4 | 2.5 |

| Employment in non-manual labor | 0.0 | 86.1 | |

| Employment in manual labor | 0.5 | 2.5 | |

| Self-employment | 1.1 | 5.1 | |

| Farmer | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Pensioner | 0.0 | 3.8 | |

| Unemployed | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Family status | Single | 79.7 | 12.7 |

| Married without children | 3.2 | 25.3 | |

| Married with children | 2.1 | 62.0 | |

| Stable relationship | 14.4 | 0.0 | |

| Single mother | 0.5 | 0.0 | |

| Expenditure on food purchases (PLN/weekly purchases) | Up to 100 | 8.6 | 1.3 |

| 101–200 | 40.1 | 25.3 | |

| 201–300 | 35.8 | 34.2 | |

| 301–400 | 11.2 | 27.8 | |

| 401–500 | 2.1 | 11.4 | |

| Over 500 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Description | Study Groups | I Do Not Agree | Hard to Say | I Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Respondents in the Surveyed Group | ||||

| Grocery shopping with a list of the products you need | students | 20.3 | 14.4 | 65.2 |

| employees | 15.2 | 15.2 | 69.6 | |

| Before going shopping, it is checked what products are at home | students | 8.0 | 10.2 | 81.8 |

| employees | 12.7 | 7.6 | 79.7 | |

| Checking the expiry date of food products in the shop | students | 6.4 | 18.2 | 75.4 |

| employees | 11.4 | 11.4 | 77.2 | |

| Buying products with an expiration date so short that they have to be thrown away | students | 47.6 | 25.1 | 27.3 |

| employees | 69.6 | 11.4 | 19.0 | |

| Shopping for some time in advance (e.g., for a week) and before using everything, some products are already spoiled | students | 39 | 23.5 | 37.4 |

| employees | 51.9 | 31.6 | 16.5 | |

| Shopping in the spur of the moment, when we feel hungry, we want a particular product | students | 8.0 | 4.8 | 87.2 |

| employees | 35.4 | 22.8 | 41.8 | |

| Food Waste in the Household | Students N1 = 187 | Employees N2 = 79 | Chi-Squared Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 84.49 | 77.22 | p = 0.909146 χ2 (calculated) = 4.797012 χ2 (tabular) = 5.991 |

| No | 10.70 | 20.25 | |

| I do not know | 4.81 | 2.53 |

| The Frequency of Food Waste in Households | Students N1 = 187 | Employees N2 = 79 | Chi-Squared Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of Respondents in a Given Group (Employees/Students) | |||

| Food is not thrown away | 2.1 | 12.7 | p = 0.998052 χ2 (calculated) = 24.41945 χ2 (tabular) = 15.507 |

| Once every few months | 9.6 | 6.3 | |

| Once a month | 10.2 | 16.5 | |

| Several times a month | 7.5 | 10.1 | |

| Once every few weeks | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| Every two weeks | 2.7 | 7.6 | |

| Once a week | 20.3 | 16.5 | |

| A few times a week | 42.2 | 29.1 | |

| Daily | 4.3 | 1.3 | |

| Food Waste at Different Stages of its Preparation for Consumption | Students N1 = 187 | Employees N2 = 79 | Chi-Squared Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food storage | 34.2 | 51.9 | p = 0.999730 χ2 (calculated) = 19.02247 χ2 (tabular) = 7.815 |

| Peparing of meals | 13.4 | 5.1 | |

| Kitchen and plate leftovers | 51.9 | 36.7 | |

| Food is not thrown away | 0.5 | 6.3 |

| Description | Study Groups | Very Rarely/ Never/Sporadically | Sometimes/ Quite Often | Always/Very Often + Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Respondents in the Surveyed Group | ||||

| Buying too much food | Students | 67.9 | 19.8 | 12.3 |

| Employees | 62.0 | 13.9 | 24.1 | |

| Buying food without a shopping list | Students | 60.4 | 21.9 | 17.6 |

| Employees | 65.8 | 25.3 | 8.9 | |

| Purchase of unnecessary products under the influence of marketing tricks (e.g., promotional price, multipacks) | Students | 55.6 | 26.2 | 18.2 |

| Employees | 68.4 | 17.7 | 13.9 | |

| No idea for using the purchased products | Students | 62.6 | 25.7 | 11.8 |

| Employees | 81.0 | 12.7 | 6.3 | |

| Preparing too-large meal portions | Students | 43.9 | 28.9 | 27.3 |

| Employees | 55.7 | 25.3 | 19.0 | |

| Storing food in inappropriate conditions | Students | 67.9 | 20.9 | 11.2 |

| Employees | 79.7 | 10.1 | 10.1 | |

| Exceeding of the expiry date | Students | 49.7 | 27.8 | 22.5 |

| Employees | 54.4 | 27.8 | 17.7 | |

| Bad quality of purchased products | Students | 70.6 | 22.5 | 7.0 |

| Employees | 82.3 | 11.4 | 6.3 | |

| Food spoilage due to over-storage | Students | 47.1 | 28.3 | 24.6 |

| Employees | 51.9 | 22.8 | 25.3 | |

| The belief that food is cheap and therefore easy to throw away | Students | 81.3 | 12.8 | 5.9 |

| Employees | 97.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| Amount of Money Lost Due to Food Waste Per Week (as % of the Total Value of Food Purchases) | Students N1 = 187 | Employees N2 = 79 | Chi-Squared Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| I do not waste/throw away food | 8.0 | 1.3 | p = 0.989726 χ2 (calculated) = 18.404 χ2 (tabular) = 14.067 |

| 0–15% of the purchase value | 57.2 | 74.7 | |

| 16–30% of the purchase value | 23.5 | 8.9 | |

| 31–45% of the value of purchases | 1.6 | 0.0 | |

| 46–60% of the value of purchases | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| 61–75% of the value of purchases | 0.5 | 0.0 | |

| Above 75% | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| I have no opinion/cannot define | 8.0 | 15.2 |

| Statements | Study Groups | Totally Unimportant + Never Mind | Hard to Say | Important + Very Important |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Respondents in the Surveyed Group | ||||

| Waste of your own money | students | 7.0 | 7.5 | 85.6 |

| employees | 2.5 | 5.1 | 92.4 | |

| High food prices | students | 7.5 | 23.5 | 69.0 |

| employees | 29.1 | 20.3 | 50.6 | |

| Fluctuating food prices | students | 7.5 | 41.2 | 51.3 |

| employees | 32.9 | 31.6 | 35.4 | |

| The occurrence of hunger and malnutrition | students | 5.9 | 10.7 | 83.4 |

| employees | 8.9 | 10.1 | 81.0 | |

| Reduced food availability | students | 16.0 | 33.2 | 50.8 |

| employees | 16.5 | 26.6 | 57.0 | |

| Less food offered | students | 18.7 | 43.9 | 37.4 |

| employees | 40.5 | 26.6 | 32.9 | |

| Waste of raw materials, energy, water, etc. consumed in the production and supply of food | students | 7.5 | 16.6 | 75.9 |

| employees | 2.5 | 12.7 | 84.8 | |

| Redundant use of farmland and water resources | students | 5.9 | 23.0 | 71.1 |

| employees | 10.1 | 20.3 | 69.6 | |

| Increasing greenhouse gas emissions | students | 11.2 | 22.5 | 66.3 |

| employees | 7.6 | 21.5 | 70.9 | |

| Wasting human labor | students | 8.0 | 20.3 | 71.7 |

| employees | 5.1 | 17.7 | 77.2 | |

| Losses in the country’s economy | students | 11.8 | 25.1 | 63.1 |

| employees | 8.9 | 26.6 | 64.6 | |

| Necessity to liquidate/utilise wasted | students | 9.1 | 17.6 | 73.3 |

| employees | 3.8 | 13.9 | 82.3 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przezbórska-Skobiej, L.; Wiza, P.L. Food Waste in Households in Poland—Attitudes of Young and Older Consumers towards the Phenomenon of Food Waste as Demonstrated by Students and Lecturers of PULS. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073601

Przezbórska-Skobiej L, Wiza PL. Food Waste in Households in Poland—Attitudes of Young and Older Consumers towards the Phenomenon of Food Waste as Demonstrated by Students and Lecturers of PULS. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073601

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzezbórska-Skobiej, Lucyna, and Paulina Luiza Wiza. 2021. "Food Waste in Households in Poland—Attitudes of Young and Older Consumers towards the Phenomenon of Food Waste as Demonstrated by Students and Lecturers of PULS" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073601

APA StylePrzezbórska-Skobiej, L., & Wiza, P. L. (2021). Food Waste in Households in Poland—Attitudes of Young and Older Consumers towards the Phenomenon of Food Waste as Demonstrated by Students and Lecturers of PULS. Sustainability, 13(7), 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073601