Abstract

Innovation districts, as a particular place for knowledge-based urban development strategies, have been praised for promoting sustainable economic developments. They have, however, been criticized for contributing to gentrification, urban inequality, and other problems that hinder sustainability. There has been little research addressing how planners maintain economic sustainability and promote the social and environmental sustainability of innovation districts. This paper takes Hangzhou as a case study, using the policy zoning—a new zoning method based on suitability evaluation—to formulate the applicable place plan for building innovation districts. The results show that the policy zoning can help planners arrange the construction of innovation districts in certain urban areas and take the most targeted measures to improve the sustainability of possible innovation districts. These measures include either enhancing the foundations of the metropolitan area or promoting innovation development by referring to suitability evaluation results. Planning based on policy zoning is of benefit to the sustainability of innovation districts through avoiding the impulsive behavior of policymakers, as well as promoting the better distribution of development achievements among the people, rather than concentrating on land developers and stakeholders who pursue maximum profits.

1. Introduction

In the past half-century, since the crisis of Fordism, the knowledge economy has become the key to economic growth, and innovation has become the center for achieving sustainable socioeconomic development [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The innovation spaces become the “highest and best use” to enhance the urban competitiveness according to many land-use policies and urban planning practices [7,8,9,10,11]. Since KBUD (knowledge-based urban development) has become an increasingly common element of urban planning and strategy making [7], innovation districts—as a new land-use type and a place-based strategy for urban renewal—combine KBUD with urban space and has become a global phenomenon in many cities. Barcelona (Spain), Boston (America), Gainesville (America), Chattanooga (America), Avondale (America), Montréal (Canada), Oklahoma (America), Rotterdam (the Netherlands), Indianapolis (America), and Sydney (Australia) are some of the cities that are building their version of an innovation district. Innovation districts have been transformed from a geographic phenomenon mentioned by Katz into a local economic development strategy to accelerate the technological innovation process and stimulate economic prosperity by clustering knowledge companies and workers [12,13]. Innovation districts, focusing on growing jobs in productive, innovative, and traded sectors, have significantly contributed to sustainable economic developments [13,14,15].

Although innovation districts bring more vitality to cities, are innovation districts an ideal model for sustainable KBUD? Innovation districts have also attracted some criticisms, including threatening the natural environment, increasing the surrounding property prices, and escalating inequality in neighborhoods [16]. And one of the most unexpected outcomes is that innovation districts promote gentrification and economic, social, and racial polarization due to a neoliberal agenda [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Driven by the market, the most profitable places are developed into innovation districts. In contrast, those with better suitability and that need to be developed are often neglected [15,20,23,24], which leads to a high level of negative externality spillover and threatens the sustainable development of cities [20]. The academic literature has extensively evaluated and been aware of the negative impact of knowledge economy on urban structure and proposed some policies to mitigate the negative externalities and enhance the sustainability of innovation districts. But there is no specific planning method for spatial support on these policies [18,20,21,22]. Therefore, this paper asks the following question: What should planners do to mitigate the negative externalities of adopting a place-based KBUD strategy, such as innovation districts, with the planning goal to develop a sustainable knowledge economy?

Zoning is a ubiquitous land-use planning and regulatory mechanism [25] in the industrial society that has a broad and significant impact on the spatial distribution of economic activity [26]. This paper proposes that zoning is still an effective way to promote the knowledge economy’s sustainable development. However, to adapt to the post-industrial society in which the mode of production has shifted from machine production to knowledge production, the rigid zoning currently in use needs to be changed accordingly. In China, there is a rising zoning method that is expected to accommodate this change, called policy zoning. By using the policy zoning method, policymakers can adopt flexible policy regulation, targeting better development of innovation districts with different goals [27].

This paper takes Hangzhou, China, as a typical case study to conduct policy zoning through spatial data analysis from the perspective of technical rationality, pointing out suitable places for innovation districts and providing a policy guide to achieve sustainable development goals. This paper contributes to the literature on studies of innovation districts, policy zoning, and planning methods by a new zoning method to achieve sustainability under the guidelines of KBUD. The paper is highly relevant for policymakers and urban planners who wish to mitigate the negative externalities in creating an innovation district in their cities through space control. The paper finds that the policy zoning can help rationally arrange the timing of the construction of innovation districts and improve the sustainability of possible innovation districts by differentiated policy supply targeting different zones. These measures include either enhancing the foundations of the urban area or promoting innovation development progress by referring to suitability evaluation results. Through policy zoning, the plan can avoid the impulsive behavior of policymakers and facilitate better distribution of development achievements among the people, which is a benefit for the sustainable development of cities. Policy zoning can also play an important role in other cities in the world, except China, although limited efforts should be made in localization.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Innovation Districts: The Origin and the Sustainability

In the 1990s, there appeared to be times of profound transformation and change in the structure and organization of the modern Western economy and society. To cope with the Fordism crisis and adapt to globalization, terms such as “post-Fordist”, “post-industrial” have been coined to describe the emerging new age of capitalism and stood out in the debate [28].

The literature on post-Fordist still takes the industrialization process as the center of analysis [29]. In terms of spatial organization, the “new industrial district” (NID) appeared based on the phenomenon of successful expansion of mature industries in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy [30,31,32,33]. The emergence of NID has revived Marshall’s industrial districts theory, emphasizing the geographical concentration of “flexible and specialized” enterprises with small and medium-size, rather than the previous spatial organization model attached to large enterprises [15,34,35,36,37]. NIDs have small and innovative firms embedded within a regionally cooperative industrial governance system, enabling them to adapt and flourish despite globalization [38]. Since then, innovation, which occurs when new or improved ideas, products, services, technologies, or processes create new market demands or cutting-edge solutions for economic, social, and environmental challenges [13], has attracted wide attention.

The literature on post-industrial is deeply influenced by Bell’s study, which points out the significant change in capitalist production mode–knowledge would replace machine to become the axis principle of social production organization [39]. Scientists, professionals, technical experts, and workers would play a prominent role; thus, innovation would become the driving force of economic growth. A series of terms, such as knowledge economy [40,41,42,43], knowledge-based urban development [7,44,45], came into focus. In the Western world, the change in production structure has aggravated the transformation of social structure. The number of people engaged in the service industry has been surging, and the “new middle class” has been continually expanding, which to a large extent, has promoted gentrification. The re-urbanization and urban renewal movement emerged with the separation of innovation and the production process. The innovation department began to receive extensive attention in the urban spatial organization.

Compared with the post-Fordist emphasizing the marginal innovation carried out by the innovation department embedded in the industrial districts, the post-industrial society (or the knowledge society) directly breaks the spatial connection between innovation and production. Today, the spatial organization of KBUDs, driven by globalization, seems more inclined to the post-industrial society, which had a “core and periphery” spatial structure on the urban, regional, or global scale [46]. With industrial activities declining in most major metropolitan regions, the primary challenge for cities is to create new types of opportunities and to develop in a way that is sustainable culturally and environmentally [47].

In the 21st century, knowledge generation and innovation have taken prevalence in most developed cities globally. In the past few decades, the accumulation of innovation has been widely studied, and the terms, such as “innovation clusters” [48,49], “innovative milieu” [50], “knowledge (community) precincts” [51], “high-technology district” [52], have sprung up. Many researchers believe that those urban KISs (knowledge and innovation spaces) are the growth engines aimed at holistic and sustainable growth in terms of economy, society, governance, and environment [53,54,55]. And the longest studied KIS—science and technology parks, have been established in many cities [56,57,58], which shows a trend that many of these metaphysical concepts in the literature are adopted by policymakers into projects to select and develop a knowledge location. For planners, these concepts become references to a form of spatial organization, which become place-based initiatives aimed at agglomerating knowledge-based activities in designated city districts [58,59]. More land-use projects that emphasize innovation are being continuously promoted, such as science and technology parks [60,61], enterprise zones [62,63,64]. In addition, “power of Times” has promoted the formation of the concept of innovation districts [54].

Since Katz and colleagues identified three general types of innovation districts based on different regional or national contexts [13,65], the term “innovation districts” has transformed from new geography to a general concept and then to a specific policy goal for sustainable KBUDs and a new spatial form of innovative agglomeration. The innovation district is used to describe a place with high quality of life and integration of work, housing, and recreation, where leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and accelerators. Innovation districts are also physically compact, transit-accessible, and technically-wired, offering mixed-use housing, office, and retail [11,66]. Innovation districts often appear in many urban strategies and plans as a policy goal and a spatial organization form in many cities around the world, such as Barcelona, Berlin, London, Medellin, Montreal, Seoul, Stockholm, and Toronto. Research on innovation districts and their sustainability is emerging [15,52,67]. Much literature summarizes the characteristics of sustainable innovation districts that are economically and environmentally successful [11,68]. Based on research needs, the paper sorts out the spatial characteristics as following Table 1.

Table 1.

The spatial characteristics of sustainable innovation districts.

2.2. Double-Edged Sword: Sustainable Innovation Districts and the Challenges

Innovation districts have both positive and negative externalities. The most significant positive externality is knowledge spillover, which can be supported by a large amount of literature [6]. Knowledge spillover can cause enterprise agglomeration [69]. The agglomeration economy is the core of many KBUD strategies [7], involving planning commercial and industrial districts [38,70], innovative clusters, and science and technology parks of various shapes and sizes [71,72]. However, knowledge spillover effects based on the economy of agglomeration would hurt the enthusiasm of enterprises for continuous innovation due to competition and imitation [73]. Policymakers tend to provide subsidies to companies in the aggregation to internalize externalities [74,75]. However, are the subsidy policies sustainable? The evidence is both positive and negative. When targeted spatially, such fiscal incentives create spatially competitive areas where companies can establish a foothold in the market by effectively reducing the usual burden of taxes, regulation, and planning [64]. The injection of investment—both indigenous and inward, for a designated area, is a benefit in creating important financial injections to local supply chains and reducing local unemployment. The problem is many firms simply disappeared at the end of the tax rebate, creating a type of “windfall effect”. Meanwhile, with most business and employment flows originating from outside the zone area, the projects had a “cannibalizing” effect on neighboring areas while also creating a very high-cost job opportunity [64]. In addition, the more widely-prevailing view is that the regions having particular subsidy policies have been ineffective at reducing urban poverty or improving labor market outcomes [62,76]. It shows that the innovation districts may bring some problems that harm social benefits and offset economic benefits [15]. Therefore, the negative externalities of innovation districts should be discussed seriously to ensure that innovation districts can promote sustainable development.

Within neoliberal governmental rationality, individual behavior, and happiness, the “public good” and responsible government can be secured by extending the logic of the market [23]. The market logic is also reflected in a series of urban changes, such as urbanization, suburbanization, and re-urbanization. For most of the 20th century, suburbanization dominated the urban landscape of many cities in Western developed countries. However, after entering the 21st century, gentrification has grown out of its erstwhile niche status to epitomize a broad-based rehabilitation of the central city as the place to work, live, and play [77]. In Neil Smith’s foundational analysis, gentrification occurs when the rent gap between current uses of a given parcel and the potential returns on its highest and best use grows large enough to offset the costs of capital reinvestment [24]. Those innovation districts that have been redeveloped into gentrification, with new and mixed amenities and comfortable environments, exclude vulnerable groups, such as low-income people, from high-priced residences. It seems that the connections, relations, and inventions facilitated by the knowledge economy still follow patterns established by older, hierarchical, and inequitable business models and forms of accumulation [23]. Meanwhile, the emphasis is frequently placed on the importance of satisfying the unique and discerning consumer demands of highly-skilled and highly-educated people working in knowledge-based industries [15,20], so that capital can get maximum economic benefits. And there is an interesting phenomenon that in Boix and Galletto’s research, Although the cores of the largest metropolitan areas specialized in services generate 35% of Spanish innovations, the level is below Marshallian industrial districts [33]. It seems “overheated”, although the innovation district is an essential form of accumulation and development of innovation.

In summary, this paper tends to understand the following debate: Under the impetus of capital and market, policymakers and planners prefer to choose the most profitable area to build innovation districts rather than the most suitable area for revitalization. Therefore, the government has paid a very high price to stimulate the agglomeration of innovation activities, including issuing high subsidies and investing in infrastructures, which are all social welfare losses. With the disadvantaged groups being excluded from the innovation districts by the high residence price, only capital, and the middle-class benefit. That is also the reason why innovation districts prefer to be physically compact, transit-accessible and offer mixed-use housing in the policy and planning responses. Furthermore, it damages the economic and environmental sustainability goals pursued by the innovation districts [15]. To cope with these problems, what can policymakers or planners do to solve or alleviate the contradictory relationship for the sustainable development of innovation districts?

2.3. Policy Zoning: A New Zoning Method and the Sustainable Innovation Districts

About a century ago, the original purpose of zoning was to protect houses in residential areas from devaluation by industrial and apartment uses [78,79]. With the success of zoning in preserving the value of the residence, zoning was employed to do too many disparate things, which attracted some criticisms [80], such as the rigidity with using zoning to regulate land-use change [81,82]. And there is a common view that rigid zoning has become a useful tool for capital proliferation, promoting gentrification, and causes urban inequality [83]. But it is undeniable that zoning is a powerful policy tool for land-use planning, which has a broad and significant impact on the spatial distribution of economic activity [26]. Rossi-Hansberg’s research found that policy to commuting costs, labor subsidies, and zoning restrictions affected whether land use was optimal or equilibrating [84]. Moreover, in Jepson’s research, planners can more effectively use zoning ordinances to achieve sustainable development [85]. Back to the sustainable innovation districts, the diverse problems involved will not be solved by simplistic approaches with land-use management becoming more complex in an increasingly interdependent society. So, the question is: Does a new zoning method exist that is different from the restrictive and rigid zoning criticized to achieve the sustainability of innovation districts?

In China, zoning is a widely adopted urban planning method, and functional zoning is commonly employed in all types of planning. However, under China’s rapid urbanization process, rigid functional zoning has been unable to meet diversified land-use needs, especially in the construction of “science and technology parks”, “cultural and creative zones”, and “innovation districts” [86]. Recently, urban planning attributes in China have transformed from a technical and public policy tool to an essential part of the national governance system [87]. Policy zoning comes into being to adapt to this change.

Policy zoning is both a planning method and a policy tool, which divides the urban planning area into a few areas according to a specific purpose and conducts differentiated policy [88]. Policy zoning is a flexible, dynamic, unfixed, and dialectical urban land-use mechanism, which delimits an adjustable boundary according to the comprehensive analysis of resource conditions, status quo, and prospects for development, focusing on expected goals. For instance, when the purpose is to build a sustainable innovation district, policy zoning can help to supply policy flexibly through internalizing externalities as much as possible for the area within the boundary. As a result, the government can achieve a governance optimum—to safeguard the interests of most of the people. The rising of policy zoning heralds a shift of the primary contradictions in the use of urban space—from protecting the economic interests of the middle-class to protecting the possibility of sustainable urban development. Through policy zoning, the most suitable places would be issued and developed rather than those with considerable land development profits.

In China, policy zoning is widely used in environmental management, traffic governance, regional spatial governance, spatial regulation. Although the application of policy zoning is diverse, there is no precedent for innovation districts. This paper is trying to develop policy zoning into a technological tool that can control innovation district’s externalities. This tool is objective and neutral, which can be used in most cities to respond to sustainable innovation districts.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.1.1. The Suitability Evaluation as the Foundation of Policy Zoning

Suitable evaluation is the significant foundation to identify policy zoning for sustainable innovation districts. Through the evaluation process, the appropriate places for innovation districts are identified, and policy zones are established. Then, based on the differences of different zones, policies should be flexibly formulated and implemented to achieve sustainable development of the economy, society, and environment. Since then, the initiative in the construction of the innovation districts is no longer owned by the developers pursuing the highest profit return but based on a rational choice.

How to build an evaluation system based on the purpose of sustainable innovation districts? Winden’s research offers a framework of analysis in the knowledge economy in cities, which found the knowledge-based development depended on the combination of the foundations of the urban region, progress towards a knowledge-based city, as well as the organizing capacity [89]. The factors and indicators in Winden’s research can be found in many other studies [11,68,90,91,92]. Based on the above literature, the paper proposes the suitability evaluation index system for sustainable innovation districts, as follows, Table 2.

Table 2.

The indicators of suitability evaluating index system for innovation districts.

3.1.2. Case Study in Hangzhou, China

Since 2012, China has gradually taken innovation as the primary impetus for development, as its economy faces structural problems: The growth driven by labor, land, foreign investment shows the trend of diminishing marginal benefits because of overcapacity in traditional industries. Just as the Western world did in the last century when it faced the crisis of Fordism, China has also entered such a new stage of development, beginning to focus on how to switch development impetus and transform the industrial structure. For now, innovation-driven development has become a national strategy. Therefore, KBUDs have received significant attention, and innovation has become a consideration of urban competitiveness. Meanwhile, the most developed cities in China are moving from the “incremental era” to the “inventory era”, entering a stage of large-scale inventory land renewal. If these cities want to move up the value chain of global competitiveness, it is worth considering obtaining sustainable development capabilities through promoting innovation. Among them, policymakers believe that it is feasible and effective to encourage the KBUD strategy by constructing innovation districts. And policy zoning can play an important role in identifying the suitable areas for urban renewal as well as improving the sustainability of innovation districts.

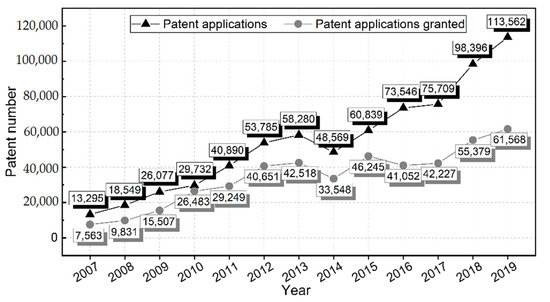

Hangzhou is a megacity located in Zhejiang province, southeastern China, near Shanghai city. The Qiantang river runs through the city, and the West Lake is the “pearl” of the city. As of 2019, the city had a population of 10.36 million totally, where 9.12 million people live in the urban district [93]. Hangzhou is not only the capital of Zhejiang Province, but also one of China’s top 10 cities in terms of population size and GDP, and top 2 in innovation competitiveness. In 2019, Hangzhou’s cumulative number of patent applications reached 113,562, of which 61,568 were granted [93], which has grown rapidly in recent years (Figure 1). According to the spatial distribution of patent, innovation in Hangzhou is concentrated in the traditional urban core areas, economic development zone, and high-tech zone [94]. As Hangzhou continues to expand in urban space, it seems to be spontaneously forming some innovation districts just like what Katz suggests the “Anchor plus” model, the “reimagined urban area” model, and the “urbanized science park” mode [13]. At the same time, the local government is making plans to promote the development of innovation in Hangzhou. According to the latest 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Hangzhou West Science and Technology Corridor, the local government hopes to build a high-quality technological innovation district, which is planned to be a world-leading digital science and technology innovation center. Due to the remarkable achievements of Hangzhou in the development of innovation and the strong willingness to seek sustainable development through the construction of innovation districts, this paper chose Hangzhou as a case study.

Figure 1.

The number of patent applications and grants in Hangzhou from 2007 to 2019.

3.2. Research Method

3.2.1. Data Collection

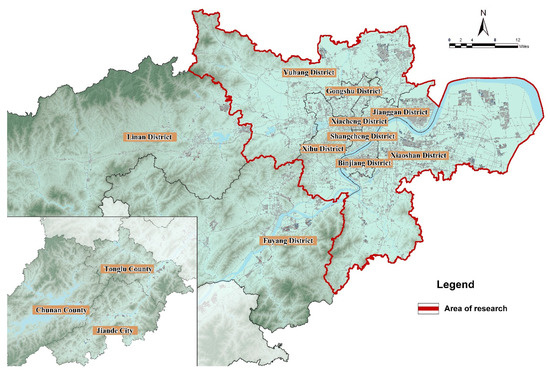

Due to the availability of spatial data, the research was based on eight administrative districts of Hangzhou, including Shangcheng District, Xiacheng District, Xihu District, Gongshu District, Jianggan District, Binjiang District, Xiaoshan District, and Yuhang District (Figure 2). These districts are the central urban areas defined in Hangzhou City Master Plan (2001–2020), gathering the political, economic, and cultural sectors. And according to Hangzhou’s statistical yearbook 2020, the population in these districts accounted for 71% of the city, and the number of patent applications accounted for 86%. Therefore, these districts are representative.

Figure 2.

Map of Hangzhou city area and the research area.

There are various ways to obtain spatial data, mainly including three kinds: One is from the government’s open data set; the second comes from available POI (Point of Interest) data; the third is provided by the related planning projects (Table 3). These data are all visualized in ArcMap10 (ESRI, Genelux, CA, USA, 2010). This paper used the kernel density tool in ArcMap10 to analyze the point data. Meanwhile, buffers were established based on line and surface data. After reclassifying the raster analysis graph, the expected result was obtained through the raster overlay tool.

Table 3.

The situation of the collected data.

3.2.2. Data Analysis—The Suitability Evaluation of Innovation Districts

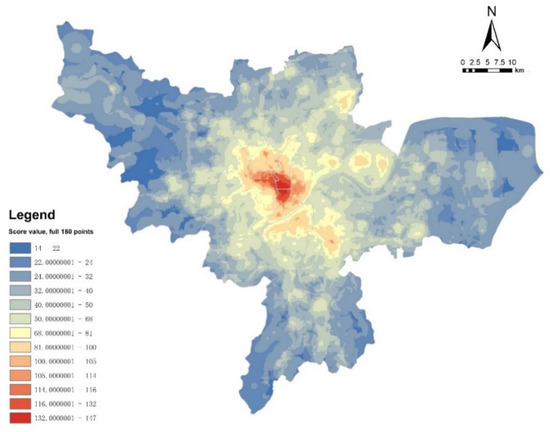

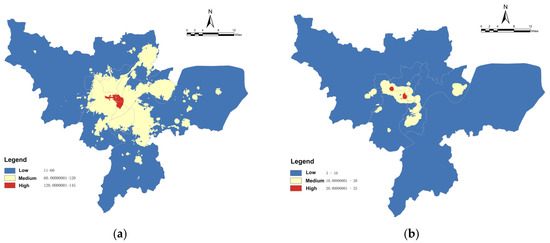

This paper performed kernel density analysis and buffer calculation for 18 data listed in “Foundations of the urban region” in Table 3 and reclassified the 18 results to uniform dimensions (the full score of each result was 10). After that, the 18 results were superimposed in ArcMap10 to obtain the urban foundations’ evaluation map, Figure 3. The color close to dark red means a higher score and better urban amenities. It shows that the quality of Hangzhou’s foundation spatially distributes approximately a circle structure and the area with the best quality centered on the location of CBD.

Figure 3.

The result of the evaluation of the foundations of Hangzhou.

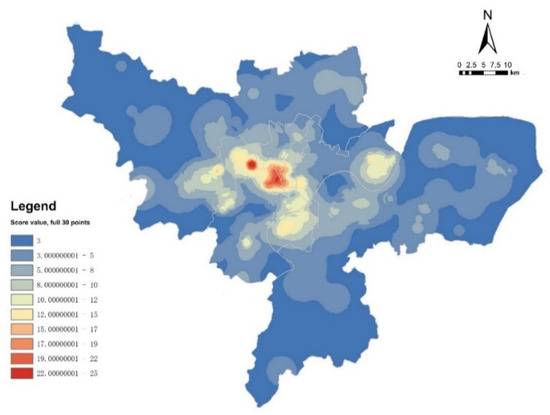

Using the same calculation in ArcMap10, this paper gets an evaluation map (Figure 4) based on three data listed in “Progress towards innovation districts” in Table 3. This map reflected two significant high-value areas, which were relatively mature in the process of innovation in Hangzhou. Meanwhile, the innovative facilities were almost located in a corridor, which ran through Zhejiang University in the northwest, the old culture and education center, CBD, and the high-tech zone in the south of the Qiantang River.

Figure 4.

The result of the evaluation of the progress towards innovation districts in Hangzhou.

To identify the urban areas suitable for innovation districts by combining the two evaluation results, the following two steps were needed:

- Reclassify each of the two evaluation results into three levels averagely: high, medium, and low.

- Overlay one reclassified result to another, find suitable differentiated zones for innovation districts according to the “foundation–progress” association relationship.

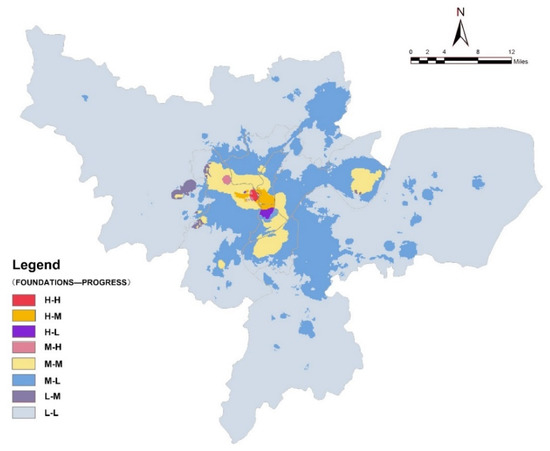

When the gap widens between each level, the view of the two evaluation results became more regular (Figure 5). Among them, the urban foundation (a) showed apparent central agglomeration, while the innovation process (b) showed the spatial pattern of two major (red) centers, one (yellow) corridor, and multiple (yellow) areas.

Figure 5.

(a) Three levels of the evaluation of the foundations; (b) Three levels of the evaluation of the progress.

When the two maps were superimposed (Figure 6), the result became both detailed and compelling. First, there was no “L–H” area, which means good innovation development and poor urban foundation are mutually exclusive to a certain degree. Second, excluding the “M–L” and “L–L” areas accounted for most of the city. The remaining urban areas were divided into six different color spots, showing a differentiated development situation. These spots are of great significance to us.

Figure 6.

The map of foundation—progress.

4. Results

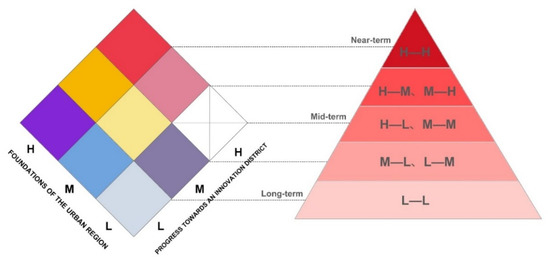

4.1. The Policy Zoning on Construction Timing of Innovation Districts in Hangzhou

Whether it is a policymaker or planner, one of the most critical issues is to build the city in order, arranging the short, medium, and long-term construction projects. With such a timetable, policymakers will be able to keep a clear head in the face of the construction of innovation districts and restrain the loss of social wealth caused by desires for quick profits, which is beneficial for sustainable development. The construction timetable itself is a content of the policy, which is also the basis for other differentiated policies. Figure 6 can help the policy zoning on construction timing of innovation districts in Hangzhou.

To form policy zoning, this paper makes a classification of the eight spots with different colors in Figure 6. The performances of different areas in foundation—progress reflected the different suitability of innovation districts. According to Figure 7, the similar parts were grouped into one category and divided into five categories. The logic of classification was based on the understanding that the better the performance of the area in the evaluations, the more suitable it is to build a sustainable innovation district in a shorter time. For example, the H–H area is the most suitable for promoting a better innovation district in the near future. On the contrary, L–L areas may need to demonstrate whether they are suitable for the construction and development of innovation districts in the distant future.

Figure 7.

Classification of the color spots according to the construction time.

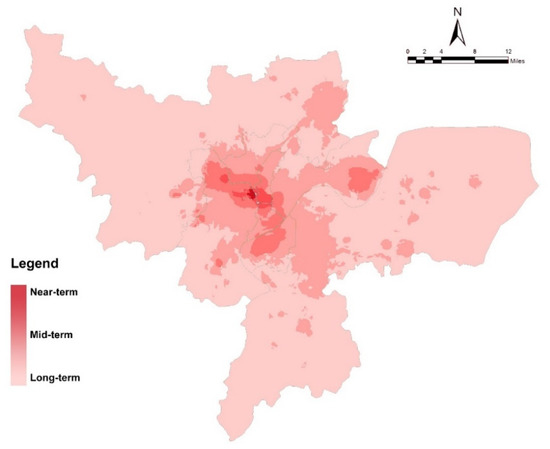

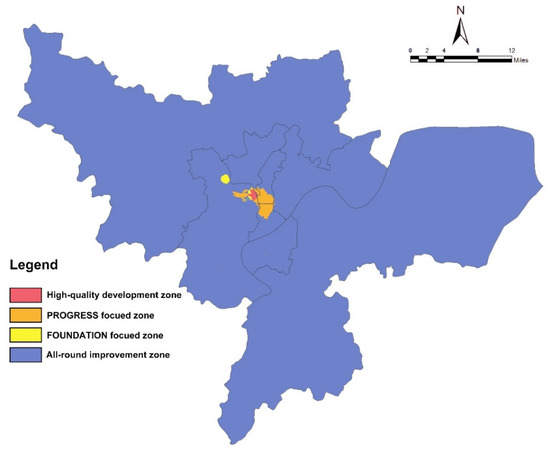

When the new classification was mapped into space, the policy zoning map, as Figure 8, was obtained, which provided a policy reference for urban areas in Hangzhou to consider the priority order of building innovation districts. It found that the areas suitable for construction in the near- and medium-term were mainly concentrated in the corridor, which can provide a useful reference for policymakers and planners.

Figure 8.

The map of policy zoning on construction timing of innovation districts in Hangzhou.

4.2. The Policy Zoning as a Guide for Sustainable Innovation Districts in Hangzhou

When developing the policy zoning on construction timing, this paper further explored the rich information in Figure 6, which led to the policy zoning as a guide for more targeted policies. The performances of different urban areas in the two evaluations were considered respectively, and a new classification for a new type of policy zoning was established as Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Classification of color spots according to their strengths and weaknesses.

In this classification, the H–H area was the most prominent and suitable in pursuing a sustainable innovation district, whose policy goal was to give full play to existing strengths and achieve high-quality, sustainable development. H–M and H–L areas had weaknesses in progress towards innovation districts, and policies should be considered to promote the progress of innovation development. Meanwhile, the policies of M–H areas were biased towards improving the foundations of the urban region. And if the rest of the urban region, including M–M, M–L, L–M, L–L areas, takes sustainable innovation districts as the development goal, more policies and efforts will be needed to promote the suitability.

With the above classification transforming into guidance spatially for policymakers to build innovation districts sustainably, this paper offers a map (Figure 10) dividing the urban region into four types of policy zones and reflecting the different development focuses for each zone. Combined with Figure 8, the paper found that most of the urban regions did not have enough suitable conditions for the development of innovation districts, with policymakers having to consider improving both the foundation and the progress in a medium or long period. The urban areas with red, orange, and yellow shown in Figure 10, could build sustainable innovation districts in a short time by targeted policies giving advantages full play and making up for shortcomings.

Figure 10.

The map of policy zoning as a guide for sustainable innovation districts in Hangzhou.

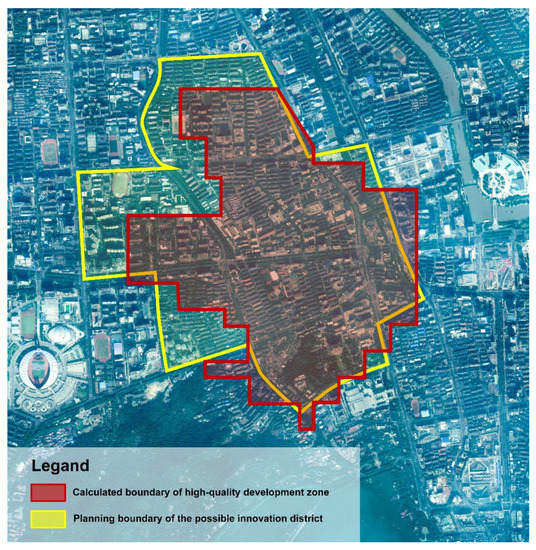

The calculation results indicated the suitable urban areas for innovation districts. However, whether the calculated boundary is accurate enough to provide a spatial reference for planners remains to be validated. Therefore, this paper took the high-quality development zone as an example, used roads and rivers as references to revise the boundaries. Then, a planning boundary of the possible innovation district was obtained as Figure 11. The result indicated that policy zoning can greatly help planners determine the spatial scope of the innovation districts during the planning process.

Figure 11.

The map of the planning boundary of a high-quality development zone.

5. Discussion

The concept of an innovation district is the policy response to the increased spatial and urban dimensions of the knowledge economy [53,95], combining innovation theories with socioeconomic trends that have emerged in the knowledge economy [12]. And although innovation districts trace their roots to agglomeration economics, advocates have placed more emphasis on urban design, policy interventions, and public–private partnerships as a means of catalyzing knowledge-intensive businesses [15,96]. However, the problem is that if the relevant policies and designs are not formulated for the goal of sustainable development, what we can see is that the development achievements are stolen by developers, contributing to increased gentrification, urban inequality, and growing gap between the rich and the poor. So, it is worth thinking about the goal of sustainable KBUDs, or innovation districts is for the benefits of the most significant number of people or for minority stakeholders to profit from it? As a response, there have been some cities implementing strategies to limit the negative externalities of innovation districts, which are appreciated in this paper. For instance, Chattanooga in America has devoted itself to ensuring the benefits from innovation districts while limiting displacement and other negative externalities arising from such urban redevelopment, with strategies and policies in socioeconomic, urban, and housing components [22]. This paper finds that the positive and negative externalities of innovation districts are mutually transformable and dialectically unified. Policies with clear sustainable development principles can make innovation districts develop towards the expectations of sustainability. Compared with traditional capital-led urban renewal programs, innovation districts with policies and strategies targeting sustainable development can bring additional benefits to local stakeholders, such as enhancing innovation capabilities and branding and could be distributed more progressively [22]. This paper, based on the relevant research [15,22,64], proposes the most essential principles for policy and urban planning (Table 4) to sustainable urbanization.

Table 4.

The policy and planning principles for sustainable innovation districts.

The policy zoning method is dedicated to finding the rational-based credible urban place to support the spatial development of innovation districts. The policy zoning method in this paper aimed to find the most suitable areas for the innovation districts rather than the areas with the most extensive capital profit margins. It can not only ensure the success of innovation districts but also choose the best possible locations, to protect the interests of local stakeholders. Policy zoning indicated such areas where targeted policies based on the principles of sustainable development can be used to influence innovation districts, thereby amplifying positive externalities and reducing negative externalities, especially those that harm the public interests. If the policy zoning was successfully adopted and implemented in Hangzhou, a future urban utopia with a sustainable vision might be seen as an evolution of the city with a narrow gap between the rich and the poor.

There has been a discussion that innovation districts will affect the spatial structure, dynamic, and pattern of the city [97]. After an urban plan is formed, including the place and boundary of innovation districts, it is worth studying how to help policymakers formulate effective policies to build a sustainable city. For instance, how the derived policy zoning matches the location of planned new urban centers and how policies should be formulated to intervene in the transition of space [98]. We hope to study and discuss them in further work.

6. Conclusions

Building innovation districts is an important growing path for cities to pursue sustainable KBUDs. More and more practices show that the construction of innovation districts is a double-edged sword, which brings both positive and negative externalities. Although innovation districts can benefit economic growth in a short time or even longer, the negative externalities spilled over weaken the ability to sustainable economic, social, and environmental development of cities. The reason is that traditional capital-led construction activities tend to overlook social issues, such as gentrification, the widening gap between rich and poor, and urban inequality, in the pursuit of maximizing profits. Thus, it deviates from the original intention of urban development—making people live better. This paper intended to change the past practice of the place-based KBUDs, and discuss the policy zoning method based on rational suitability evaluations, which takes the location of innovation districts as an example.

Policy zoning is a zoning method rising in China, aiming to achieve sustainable economic growth and improve people’s living standards by dividing the urban region into a certain number of policy zones and providing policies flexibly in real need. This paper put forward a suitability evaluation index system according to the review of the spatial characteristics of the successful innovation districts. It takes Hangzhou as a case study to complete an attempt at policy zoning. The results showed that the direct benefits of policy zoning can help policymakers arrange the timing of the construction of innovation districts and make the most effective measures either in improving foundations of the urban area or promoting the progress of innovation development.

These findings help articulate some important ideas and future steps to treat sustainable KBUDs. The research may be limited by the bounded rationality of the suitability evaluation system, the calculation through ArcMap10, as well as the limited research area. Such limits are present in similar types of research. However, as natural parts of the exploratory process, purposeful selection of index based on the goals of sustainable development and systematic analytical strategies help to attenuate their effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; Methodology, C.T.; Software, C.T.; Formal analysis, C.T.; Investigation, X.H. Resources, X.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and C.T.; Writing—review and editing, J.W. and C.T.; Visualization, C.T.; Project administration, J.W.; Funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Link, A.N.; Siegel, D.S. Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Technological Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Coad, A.; Segarra, A. Firm growth and innovation. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, D.P.; Link, A.N. Public Sector Entrepreneurship: U.S. Technology and Innovation Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.H.; Moncada-Paternò-Castello, P.; Montresor, S.; Vezzani, A. Financing constraints, R&D investments and innovative performances: New empirical evidence at the firm level for Europe. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2016, 25, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rezny, L.; White, J.B.; Maresova, P. The knowledge economy: Key to sustainable development? Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2019, 51, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. The role of R&D and knowledge spillovers in innovation and productivity. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 123, 103391. [Google Scholar]

- Benneworth, P.; Ratinho, T. Reframing the Role of Knowledge Parks and Science Cities in Knowledge-Based Urban Development. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Vinci, C.P. Innovation, Productivity and Environmental Performance of Technology Spillovers Effects: Evidence from European Patents within the Triad. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Evaluating place quality in innovation districts: A Delphic hierarchy process approach. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Carlucci, F.; Vinci, C.P.; Yigitcanlar, T. Environmental innovation, knowledge spillovers and policy implications: A systematic review of the economic effects literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Adu-McVie, R.; Erol, I. How can contemporary innovation districts be classified? A systematic review of the literature. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisson, A. Innovation districts: An investigation of the replication of the 22@ Barcelona’s Model in Boston. Master’s Thesis, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.; Wagner, J. The Rise of Innovation Districts: A New Geography of Innovation in America; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Wang, J.; Song, Y. Organization Mechanisms and Spatial Characteristics of Urban Collaborative Innovation Networks: A Case Study in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.; Sanderford, D. Innovation Districts at the Cross road of the Entrepreneurial City and the Sustainable City. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2017, 9, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Guaralda, M. How can an enhanced community engagement with innovation districts be established? Evidence from Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Cities 2020, 96, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Resseger, M.; Tobio, K. Inequality in Cities. J. Reg. Sci. 2009, 49, 617–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Stevens, Q. How Culture and Economy Meet in South Korea: The Politics of Cultural Economy in Culture-led Urban Regeneration. Int. J. Urban Reg. 2013, 37, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlin, J. The Post-Industrial “Shop Floor”: Emerging Forms of Gentrification in San Francisco’s Innovation Economy. Antipode 2016, 48, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The New Urban Crisis: Gentrification, Housing Bubbles, Growing Inequality, and What We Can Do About It Basic; Book: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morisson, A.; Bevilacqua, C. Balancing gentrification in the knowledge economy: The case of Chattanooga’s innovation district. Urban Res. Pract. 2018, 12, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastalich, W. Knowledge economy and research innovation. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Toward a Theory of Gentrification A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1979, 45, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Sanders, S.; Reed, P. Using public participatory mapping to inform general land use planning and zoning. Landsc. Urban Plan 2018, 177, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shertzer, A.; Twinam, T.; Walsh, R.P. Zoning and the economic geography of cities. J. Urban Econ. 2018, 105, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Urban Revolution; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. Post-Fordism: Models, Fantasies and Phatoms of Transition; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Huang, L. Fordism, Neo-Fordism and Post-Fordism—On Evolution of Production Mode in Developed Capitalist Countries. Teach. Res. 2005, 8, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, M.; Sabel, C. The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M. The Transition to Flexible Specialisation in the US Film Industry: External Economies the Division of Labour, and the Crossing of Industrial Divides; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, C. Revival of Marshallian Industrial District Theory and Its Theoretical Meanings. Areal Res. Dev. 2004, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. Flexible production systems and regional development: The rise of new industrial space in North America and Western Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. 2010, 12, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Macmillan: London, UK, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, E.J.; Bamford, J.; Saynor, P. Small Firms and Industrial Districts in Italy; Routledge: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Geroski, P.A.; Best, M.H. The New Competition: Institutions of Industrial Restructuring. Econ. J. 1991, 101, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, R.; Galletto, V. Innovation and Industrial Districts: A First Approach to the Measurement and Determinants of the I-District Effect. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, A. Sticky places in slippery space: A typology of industrial districts. Econ. Geogr. 1996, 72, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. The Coming of the Post-Industrial Society. Educ. Forum 1976, 40, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. The Age of Discontinuity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Luque, E. Whose knowledge (economy)? Soc. Epistemol. 2001, 15, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, G. The New Economy: What the concept owes to the OECD. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 679–690. [Google Scholar]

- Raspe, O.; Van Oort, F. The Knowledge Economy and Urban Economic Growth. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 1209–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Planning for knowledge-based urban development: Global perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.; May, T. Urban knowledge exchange: Devilish dichotomies and active intermediation. Int. J. Knowl. Based Dev. 2010, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryniewicz, J.T. Core-Periphery—An Old Theory in New Times. Eur. Polit. Sci. 2014, 13, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.V. Knowledge-based Development: Policy and Planning Implications for Cities. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.K. From Fragmentation to Integration: Development Process of Innovation Clusters in Korea. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2001, 6, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.S.; Del-Palacio, I. Global clusters of innovation: The case of Israel and Silicon Valley. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 2, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J. Critical surveys edited by Stephen Roper innovation and space: A critical review of the literature. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Taboada, M.; Pancholi, S. Place Making for Knowledge Generation and Innovation: Planning and Branding Brisbane’s Knowledge Community Precincts. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. Alternative Forms of the High-Technology District: Corridors, Clumps, Cores, Campuses, Subdivisions, and Sites. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, F.J.; Yigitcanlar, T.; García, B.; Lönnqvist, A. Knowledge and the City: Concepts, Applications and Trends of Knowledge-Based Urban Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winden, V. Creating Knowledge Locations in Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi, S. A conceptual approach for place making in knowledge and innovation spaces: Case investigations from Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M.; Hall, P. Technopoles of the World: The Making of Twenty-First-Century Industrial Complexes; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.; Quintas, P.; Wield, D. High-Tech Fantasies: Science Parks in Society, Science and Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- van Winden, W.; Carvalho, L. Urbanize or Perish? Assessing the Urbanization of Knowledge Locations in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.C.J.M.; Choi, C.J.; Chu, R.T.J. The state in science, technology and innovation districts: Conceptual models for China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2005, 17, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Vial, I.; Fernández-Olmos, M. Knowledge spillovers in science and technology parks: How can firms benefit most? J. Technol. Transf. 2015, 40, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, D.; Zhu, F. Chinese S&T parks: The emergence of a new model. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark, D.; Young, T. Enterprise zones, poverty, and labor market outcomes: Resolving conflicting evidence. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2019, 78, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, P.; North, P.; Southern, A. Ecological empowerment and Enterprise Zones: Pain free transitions to sustainable production in cities or fool’s gold? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, R.C. Enterprise zone policy: Developing sustainable economies through area-based fiscal incentives. Urban Res. Pract. 2012, 5, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.; Bradley, J. The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Place quality in innovation clusters: An empirical analysis of global best practices from Singapore, Helsinki, New York, and Sydney. Cities 2018, 74, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Huang, H.I.; Walsh, J.P. A typology of ‘innovation districts’: What it means for regional resilience. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does place quality matter for innovation districts? Determining the essential place characteristics from Brisbane’s knowledge precincts. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.S.; Strange, W.C. The Determinants of Agglomeration. J. Urban Econ. 2001, 50, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Competition, Collaboration and the New Industrial Districts: Examining the Institutional Turn in Local Economic Development. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, F.; Husted, K.; Vestergaard, J. Second generation science parks: From structural holes jockeys to social capital catalysts of the knowledge society. Technovation 2005, 25, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinho, T.; Henriques, E. The role of science parks and business incubators in converging countries: Evidence from Portugal. Technovation 2010, 30, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, A. Urban Economics. Harpercollins 2002, 2, 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Szücs, F. Do research subsidies crowd out private R&D of large firms? Evidence from European Framework Programmes. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103923. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J. Repairing the R&D market failure: Public R&D subsidy and the composition of private R&D. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark, D.; Kolko, J. Do enterprise zones create jobs? Evidence from California’s enterprise zone program. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 68, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, L.; Machado, C.; Sviatschi, M.M. Bright Minds, Big Rent: Gentrification and the Rising Returns to Skill. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, D.P.; McDonald, J.F. Land use before zoning: The case of 1920’s Chicago. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1999, 29, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischel, W.A. An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for its Exclusionary Effects. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartke, R.; Lamb, J. Upzoning, Public Policy, and Fairness—A Study and Proposal. William Mary Law Rev. 1975, 17, 701. [Google Scholar]

- Gallent, N.; Kim, K.S. Land zoning and local discretion in the Korean planning system. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P. Controlling Development: Certainty and Discretion in Europe, the USA and Hong Kong; UCL Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Housing, urban growth and inequalities: The limits to deregulation and upzoning in reducing economic and spatial inequality. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi-Hansberg, E. Optimal urban land use and zoning. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2004, 7, 69–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, E.J.; Haines, A.L. Zoning for Sustainability: A Review and Analysis of the Zoning Ordinances of 32 Cities in the United States. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2014, 80, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J. An Effective Tool for Rural and Urban Land Use Planning and Management in the Market Economy: An Introduction to the New Edition of “Code for Classification of Urban Land Use and Planning Standards of Development Lan”. Urban Plan. Forum 2011, 6, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. The Evolution of Thoughts on Urban and Rural Planning in China Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Urban Plan. Int. 2019, 34, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Committee for Terms in Sciences and Technologies. Chinese Terms in Urban and Rural Planning; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- van Winden, W.; van den Berg, L.; Pol, P. European Cities in the Knowledge Economy: Towards a Typology. Urban Stud. 2016, 44, 525–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Ruan, Y. Influence Factors of Spatial Distribution of Urban Innovation Activities Based on Ensemble Learning: A Case Study in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junyu, R.; Xiaohui, Y. Evaluation and Suggestions on the Development Level of Beijing “Innovation districts”. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2018, 3, 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Wu, D.; Marenfeng, J.Y.; Zhang, Y. Spatial-Correlation between Agglomeration of Cultural &Creative Industries and Urban Built Environment Field in Hangzhou. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 38, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hangzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Hangzhou Statistical Yearbook; China Statistic Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Lin, N. Spatial-temporal Evolution Characteristics and Countermeasures of Urban Innovation Activities Distribution Pattern: A Case Study of Hangzhou. Urban Dev. Stud. 2020, 27, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, C.; Pizzimenti, P. Urban Innovation-Oriented Policies and Knowledge Dynamics: Insights from Boston and Cambridge, US. Planum Journal—A New Cycle of Urban Planning between Tactics and Strategy. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313351236_Urban_innovation-oriented_policies_and_knowledge_dynamics_insights_from_Boston_and_Cambridge_US (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Wilson, J. Given a Hammer: Tax Increment Financing abuse in the ST. LOUIS Region. St Louis Univ. Public Law Rev. 2014, 34, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Romero De Ávila Serrano, V. Dynamics and distribution of the knowledge economy in contemporary crisis (2000–2015) in the Madrid city-region. Knowl. Man. Res. Pract. 2020, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Jin, Y.; Yan, L.; Pei, P. Aspirations and realities of polycentric development: Insights from multi-source data into the emerging urban form of Shanghai. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).