Sustainable Virtual Teams: Promoting Well-Being through Affect Management Training and Openness to Experience Configurations

Abstract

1. Introduction

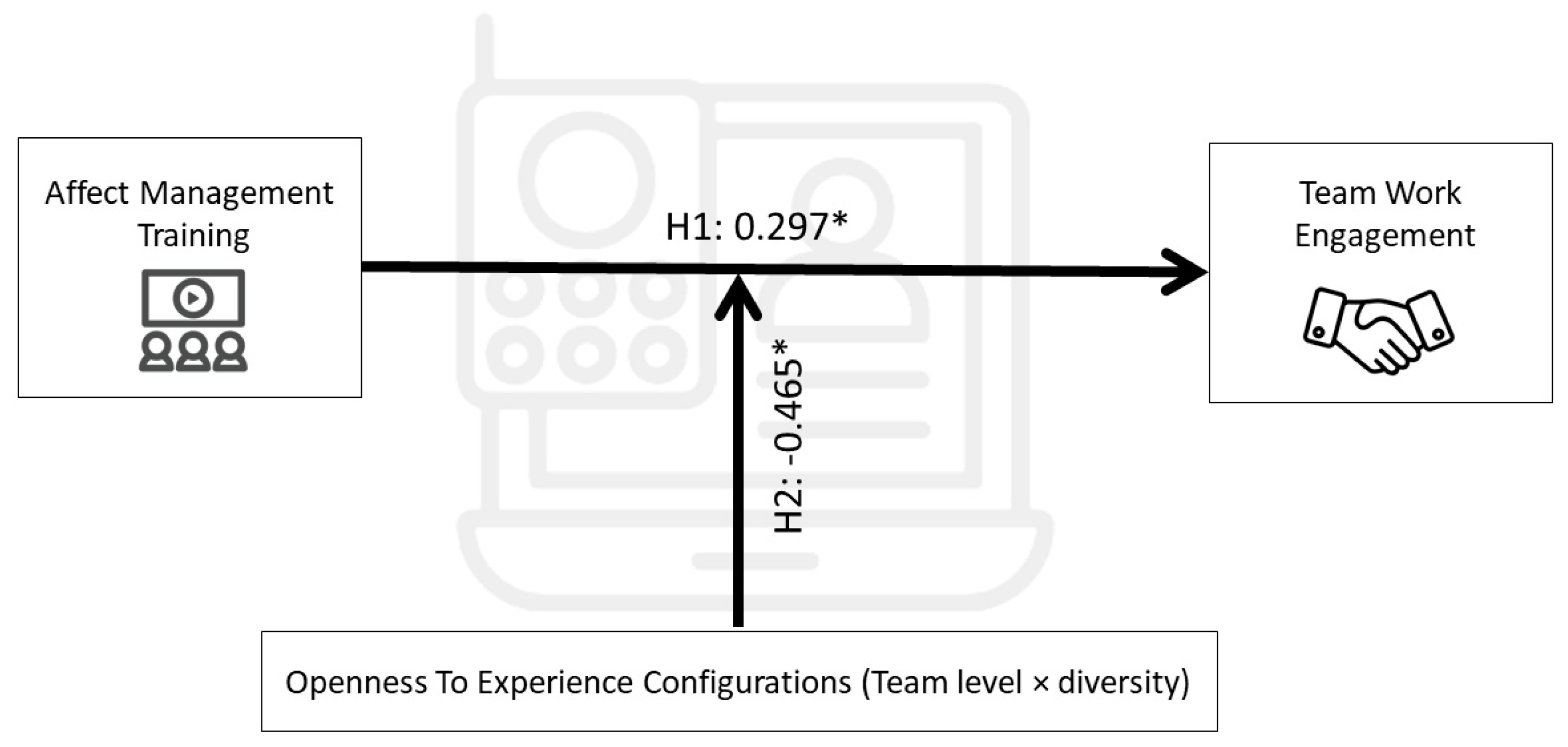

1.1. Affect Management Training and Eudaimonic Well-Being

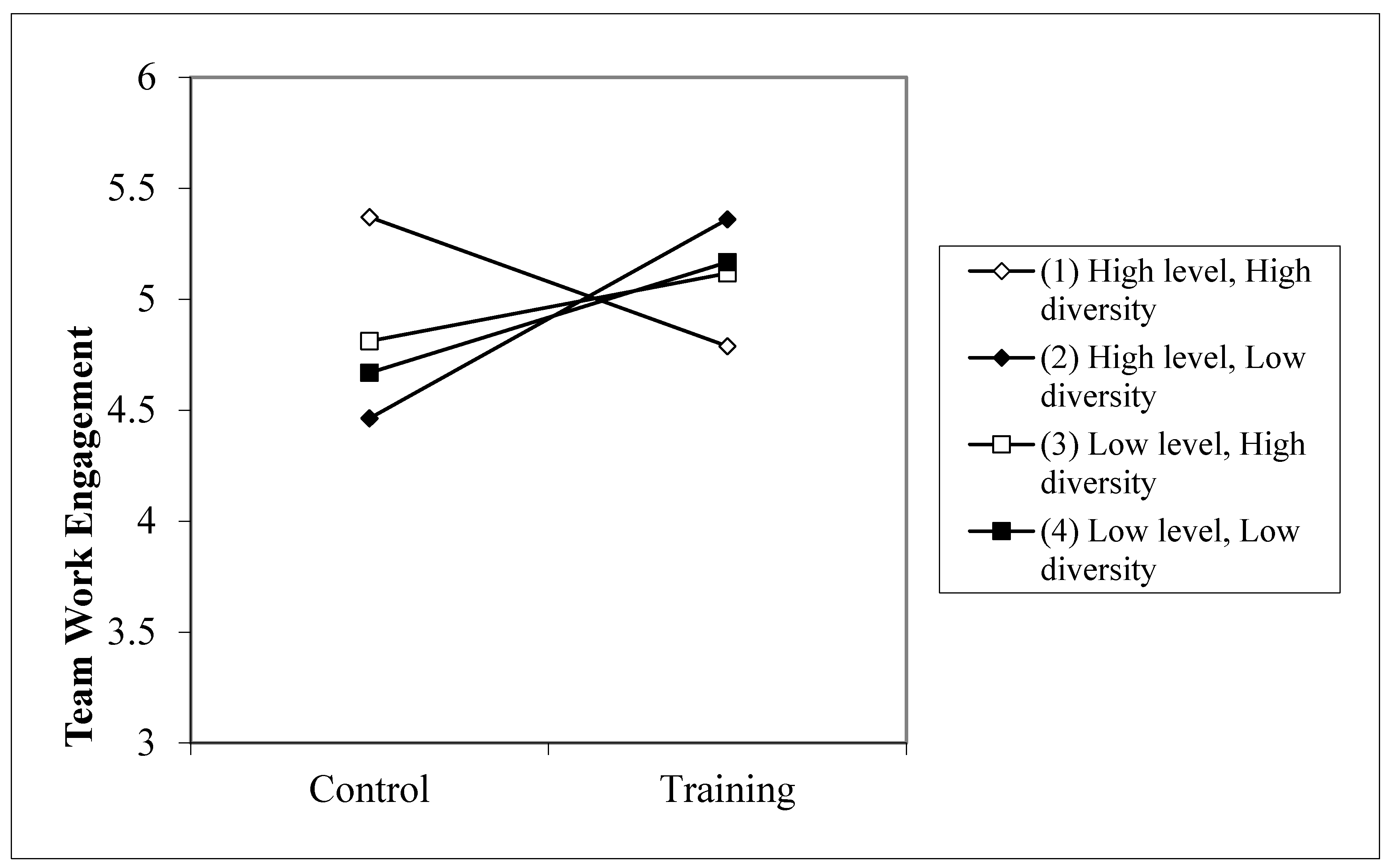

1.2. The Moderating Role of OEC

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

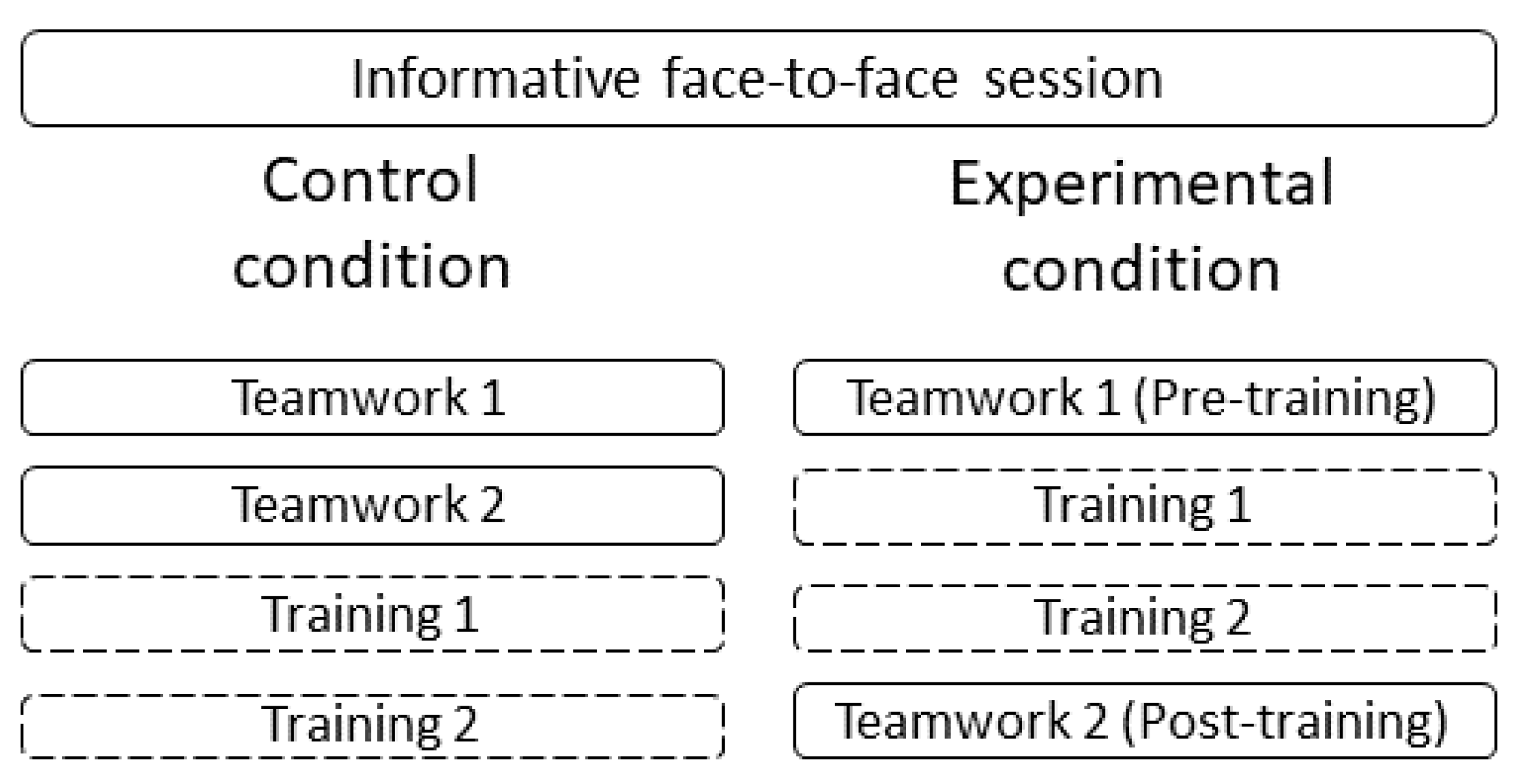

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

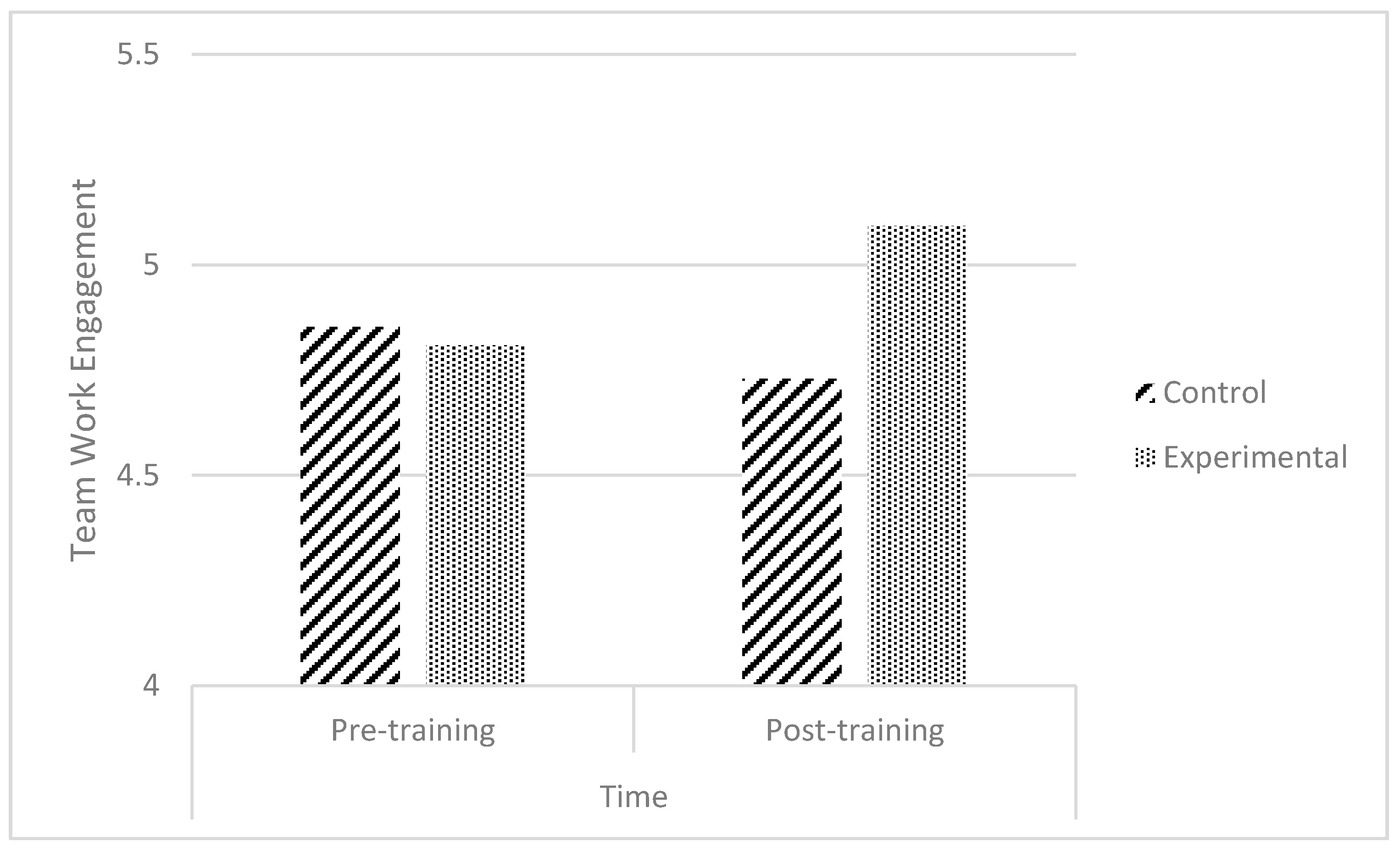

3.1. Randomization and Manipulation Checks

3.2. Preliminary Results

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayona, J.A.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M. The relationship between knowledge characteristics’ fit and job satisfaction and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villajos, E.; Tordera, N.; Peiró, J.M. Human resource practices, eudaimonic well-being, and creative performance: The mediating role of idiosyncratic deals for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J.; Montesa, D.; Soriano, A.; Kozusznik, M.W.; Villajos, E.; Magdaleno, J.; Djourova, N.P.; Ayala, Y. Revisiting the Happy-Productive Worker Thesis from a Eudaimonic Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Buades, M.E.; Peiró, J.M.; Montañez-Juan, M.I.; Kozusznik, M.W.; Ortiz-Bonnín, S. Happy-productive teams and work units: A systematic review of the ‘happy-productive worker thesis’. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, S.; Hill, N.S.; Gibbs, J.L.; Maruping, L.M. Virtual work: Bridging research clusters. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 308–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Fletcher, T.D.; Pescosolido, T.; Major, D.A. Extraversion and Leadership Emergence: Differences in Virtual and Face-to-Face Teams. Small Group Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidavičienė, V.; Al Majzoub, K.; Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, I. Factors Affecting Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, T.; Sarti, D. The “ Way ” Toward E-leadership: Some Evidence From the Field. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, C.D. Introduction Group dynamics when battling a pandemic. Group Dyn. 2020, 24, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, G.; Geister, S.; Konradt, U. Managing virtual teams: A review of current empirical research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2005, 15, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Leidner, D.E. Communication and trust in global virtual teams. J. Comput. Commun. 1998, 10, 791–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovic, M.; Hammond, M.; Lenhardt, J.; Palanski, M.; Olabisi, J. Teaching Virtual and Cross-Cultural Collaborations: Exploring Experiences of Croatia- and U.S.-Based Undergraduate Students. J. Manag. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Beyerlein, M. Framing the Effects of Multinational Cultural Diversity on Virtual Team Processes. Small Group Res. 2016, 47, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, D.; Mell, J.N. Past, present, and potential future of team diversity research: From compositional diversity to emergent diversity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Maznevski, M.L.; Voigt, A.; Jonsen, K. Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, F.F.; Makhecha, U.P. Drivers of Employee Engagement in Global Virtual Teams. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 23, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, M. Faultlines as the “Earth’s Crust”: The Role of Team Identification, Communication Climate, and Subjective Perceptions of Subgroups for Global Team Satisfaction and Innovation. Manag. Commun. Q. 2019, 33, 581–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.T.; Staples, D.S. Reducing Faultlines in Geographically Dispersed Teams: Self-Disclosure and Task Elaboration. Small Group Res. 2013, 44, 498–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, D.C.; Murnighan, J.K. Demographic Diversity and Faultlines: The Compositional Dynamics of Organizational Groups. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, S.M.B.; Patel, P.C. Group Faultlines: A Review, Integration, and Guide to Future Research. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 969–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.K.; Bettenhausen, K.; Gibbons, E. Realities of working in virtual teams: Affective and attitudinal outcomes of using computer-mediated communication. Small Group Res. 2009, 40, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, R.; Sánchez-Manzanares, M.; Antino, M.; Lau, D. Bridging team faultlines by combining task role assignment and goal structure strategies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valls, V.; Tomás, I.; González-Romá, V.; Rico, R. The influence of age-based faultlines on team performance: Examining mediational paths. Eur. Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Glenz, A.; Antino, M.; Rico, R.; González-Romá, V. Faultlines and Subgroups: A Meta-Review and Measurement Guide. Small Group Res. 2014, 45, 633–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronas, T.T.; Oliva, M.A.; Luna, J.C.Y.; Palma, A.M.L. Virtual teams in higher education: A review of factors affecting creative performance. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2015, 369, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, J.; Salas, E. Today’s virtual teams: Adapting lessons learned to the pandemic context. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restubog, S.L.D.; Ocampo, A.C.G.; Wang, L. Taking control amidst the chaos: Emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, N. Coping with coping strategies: How distributed teams and their members deal with the stress of distance, time zones and culture. Stress Health 2011, 27, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Nachreiner, F.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Rodriguez-Montalbán, R.; Acevedo-Soto, E.; Lugo, K.N.; Torres-Oquendo, F.; Toro-Alfonso, J. Self-Efficacy and Openness to Experience as Antecedent of Study Engagement: An Exploratory Analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 2163–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Shang, L.; Meng, Q. Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model to exploring predictors of innovative teaching among university teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 89, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-castaño, E.; Sánchez-García, J.; Garrigos-simon, F.J.; Guijarro-García, M. The Influence of Management on Teacher Well-Being and the Development of Sustainable Schools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The impact of E-mail communication on organizational life. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cybersp. 2010, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E. Turn Digitalization and Automation to a Job Resource. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente, P.; Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.B. From “I” to “We”: The Factorial Validity of a Team Work Engagement Scale. In Occupational Health Psychology: From Burnout to Well-Being; Neves, J., Gonçalves, S.P., Eds.; Edições Sílabo: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012; pp. 334–355. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.L.; Passos, A.M.; Bakker, A.B. Team Work Engagement: Considering Team Dynamics for Engagement; ISCTE-IUL, Business Research Unit (BRU-IUL): Lisbon, Portugal, 2012; pp. 2–37. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martínez, I.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Perceived collective efficacy, subjective well-being and task performance among electronic work groups: An experimental study. Small Group Res. 2003, 34, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Passos, A.M.; Bakker, A. Empirical validation of the team work engagement construct. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Xu, L.; Liang, L.; Chaudhry, S.S. The impact of team task and job engagement on the transfer of tacit knowledge in e-business virtual teams. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2012, 13, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Gibson, C.B.; Grushina, S.V.; Patrick, D.; Gibbs, J.L.; Gibson, C.B. Understanding orientations to participation: Overcoming status differences to foster engagement in global teams engagement in global teams ARTICLE HISTORY. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual Teams Research: 10 Years, 10 Themes, and 10 Opportunities. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.A.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zaccaro, S.J. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Knight, A.P. Group Affect. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.B. “Yes, I Can, I Feel Good, and I Just Do It!” On Gain Cycles and Spirals of Efficacy Beliefs, Affect, and Engagement. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 60, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, N.; González-Romá, V. Affective Climate in Teams. In The Cambridge Handbook of Workplace Affect; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, D.; Fischer, A.H.; Bos, A.E.R. The role of emotion in computer-mediated communication: A review. Comput. Human Behav. 2008, 24, 766–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshin, A.; Rafaeli, A.; Bos, N. Anger and happiness in virtual teams: Emotional influences of text and behavior on others’ affect in the absence of non-verbal cues. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 116, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E. Team Training Essentials: A Research-Based Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781138814219. [Google Scholar]

- Panteli, N.; Yalabik, Z.Y.; Rapti, A. Fostering work engagement in geographically-dispersed and asynchronous virtual teams. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A. Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Ilgen, D.R.; Lepine, J.A.; Sheppard, L. Computer-assisted communication and team decision-making performance: The moderating effect of openness to experience. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, A.C.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Humphrey, S.E.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Ilgen, D.R.; Van Kleef, G.A. Facing differences with an open mind: Openness to experience, salience of intragroup differences, and performance of diverse work groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.T. Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, L.M.; Peterson, R.S. 7. A contingent configuration approach to understanding the role of personality in organizational groups. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 327–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Burnett, D.D. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Thomas, C.L.; Yu, J.; Spitzmueller, C. Explaining benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of engagement, team proactivity composition and perceived organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 101, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfhill, T.; Sundstrom, E.; Lahner, J.; Calderone, W.; Nielsen, T.M. Group personality composition and group effectiveness an integrative review of empirical research. Small Group Res. 2005, 36, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Angell, L.C. Personality heterogeneity in teams: Which Differences Make a Difference for Team Performance? Small Group Res. 2003, 34, 651–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, G.A.; Wagner, S.H.; Christiansen, N.D. The Relationship between Work-Team Personality Composition and the Job Performance of Teams. Group Organ. Manag. 1999, 24, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prewett, M.S.; Brown, M.I.; Goswami, A.; Christiansen, N.D. Effects of Team Personality Composition on Member Performance: A Multilevel Perspective. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 316–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balthazard, P.; Potter, R.E.; Warren, J. Expertise, Extraversion and Group Interaction Styles as Performance Indicators in Virtual Teams. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2004, 35, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.A.G.; Van Tuijl, H.F.J.M.; Rutte, C.G.; Reymen, I.M.M.J. Personality and team performance: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Personal. 2006, 20, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipelman, B.A.; Rice, E.L.; Vogel, A.L.; Hall, K.L. The Role of Team Personality in Team Effectiveness and Performance. In Strategies for Team Science Success: Handbook of Evidence-Based Principles for Cross-Disciplinary Science and Practical Lessons Learned from Health Researchers; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.H. The role of group personality composition in the emergence of task and relationship conflict within groups. J. Manag. Organ. 2009, 15, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vianen, A.E.M.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Personality in teams: Its relationship to social cohesion, task cohesion, and team performance. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, J.R. The role of editing in knowledge development: Consensus shifting and consensus creation. In Opening the Black Box of Editorship; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008; pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.E.; Dulebohn, J.H. Team personality composition, emergent leadership and shared leadership in virtual teams: A theoretical framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Dynamics of Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 261–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D. Happiness at Work. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward Job Demands—Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.; Schultze, M.; West, S.G.; Krumm, S. The Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other Characteristics Required for Face-to-Face Versus Computer-Mediated Communication: Similar or Distinct Constructs? J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Hoch, J.E. Virtual teams in organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, L.; Ripoll, P.; Peiró, J.M.; Van Dick, R. Loafing in the digital age: The role of computer mediated communication in the relation between perceived loafing and group affective outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Barsade, S.G. Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; Scherer, K.R. Body movement and voice pitch in deceptive interaction. Semiotica 1976, 16, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.; Krumm, S. The “virtual team player”: A review and initial model of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics for virtual collaboration. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 7, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Lengel, R.H. Organizational Information Requirements, Media Richness and Structural Design. Manag. Sci. 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K. Carrying too heavy a load? The communication and miscommunication of emotion by email. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Dorris, A.D. Emotions in the Workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luse, A.; McElroy, J.C.; Townsend, A.M.; Demarie, S. Personality and cognitive style as predictors of preference for working in virtual teams. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleman, E. Diversity in demographic characteristics, abilities and personality traits: Do faultlines affect team functioning? Group Decis. Negot. 2005, 14, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.; Stewart, G.L. Composition, process, and performance in self-managed groups: The role of personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Y.C.; Owens, B.P.; Tesluk, P.E. Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1705–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.A.G.; Rutte, C.G.; Van Tuijl, H.F.J.M.; Reymen, I.M.M.J. The big five personality traits and individual satisfaction with the team. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, M.C.; Herold, D.M.; Shalley, C.E. Members’ openness to experience and teams’ creative performance. Small Group Res. 2011, 42, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Bhave, D.P.; Johnson, T.D. Personality and group performance: The importance of personality composition and work tasks. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 58, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Klein, K.J. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–90. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, S.E.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Meyer, C.J.; Ilgen, D.R. Trait configurations in self-managed teams: A conceptual examination of the use of seeding for maximizing and minimizing trait variance in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korukonda, A.R. Differences that do matter: A dialectic analysis of individual characteristics and personality dimensions contributing to computer anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1921–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, F.J. Having an open mind: The impact of openness to experience on interracial attitudes and impression formation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vreede, T.; De Vreede, G.J.; Ashley, G.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Exploring the effects of personality on collaboration technology transition. Proc. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst. Sci. 2012, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hooff, B.; de Leeuw van Weenen, F. Committed to share: Commitment and CMC use as antecedents of knowledge sharing. Knowl. Process Manag. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, C.A.; Pharmer, J.A.; Salas, E. When member homogeneity is needed in work teams: A meta-analysis. Small Group Res. 2000, 31, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, Q.M.; Sturman, M.C.; Simons, T.L. Does the measure of dispersion matter in multilevel research?: A comparison of the relative performance of dispersion indexes. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 564–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Crawford, E.R.; Methot, J.R. A review of research on personality in teams: Accounting for pathways spanning levels of theory and analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martínez, L.; Er, E.; Martínez-Monés, A.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Bote-Lorenzo, M.L. Creating collaborative groups in a MOOC: A homogeneous engagement grouping approach. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, R.; Vantilborgh, T.; Bal, M.; Lub, X. Creating inclusive teams through perceptions of supplementary and complementary person–team fit: Examining the relationship between person–team fit and team effectiveness. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 41, 310–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, A.C.; van Knippenberg, D.; Van Kleef, G.A.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Bridging Faultlines by Valuing Diversity: Diversity Beliefs, Information Elaboration, and Performance in Diverse Work Groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Shemla, M.; Schermuly, C.C. Social category salience moderates the effect of diversity faultlines on information elaboration. Small Group Res. 2011, 42, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.E. Groups: Interaction and Performance; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Moreno, E.; Zornoza, A.; Orengo, V.; Thompson, L.F. The effects of team self-guided training on conflict management in virtual teams. Group Decis. Negot. 2015, 24, 905–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, Y.M.; Scissors, L.E.; Gill, A.J.; Gergle, D. Online chronemics convey social information. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovholt, K.; Grønning, A.; Kankaanranta, A. The Communicative Functions of Emoticons in Workplace E-Mails::-) Email literacy in the workplace View project Feedback and advice giving in teacher-student supervision View project. Artic. J. Comput. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet-Martínez, V.; John, O.P. Los Cinco Grandes Across Cultures and Ethnic Groups: Multitrait Multimethod Analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, G.P.; Henn, C.M. Dimensionality of the 9-item Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES-9). Psychol. Rep. 2013, 112, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, M.T.; Mathieu, J.E.; Gilson LL, R.; Sanchez, D.; Dean, M.D. Do I Really Know You and Does It Matter? Unpacking the Relationship Between Familiarity and Information Elaboration in Global Virtual Teams. Group Organ. Manag. 2019, 44, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Erkens, G.; Kirschner, P.A.; Kanselaar, G. Influence of group member familiarity on online collaborative learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenfeld, D.H.; Mannix, E.A.; Williams, K.Y.; Neale, M.A. Group composition and decision making: How member familiarity and information distribution affect process and performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Mohammed, S.; Mcgrath, J.E.; Florey, A.T.; Vanderstoep, S.W. Time matters in team performance: Effects of member familiarity, entrainment, and task discontinuity on speed and quality. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 633–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locklear, L.R.; Taylor, S.G.; Ambrose, M.L. How a Gratitude Intervention Influences Workplace Mistreatment: A Multiple Mediation Model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, B.A.; Molix, L.; Talley, A.; Eubanks, J.P. Numerical representation and cross-cut role assignments: Majority members’ responses under cooperative interaction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A.L.; Jordan, P.J.; Lawrence, S.A.; Troth, A.C. Positive affective tone and team performance: The moderating role of collective emotional skills. Cogn. Emot. 2016, 30, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz Vergel, A.I.; Kuntze, J. Student engagement and performance: A weekly diary study on the role of openness. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 39, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Montealegre, R. How Technology Is Changing Work and Organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Anta, B.; Orengo, V.; Zornoza, A.; Peñarroja, V.; Martínez-Tur, V. Understanding the Sense of Community and Continuance Intention in Virtual Communities: The Role of Commitment and Type of Community. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Gallagher, P.T.; Domingo, M.A.; Klock, E.A. Embracing Complexity: Reviewing the Past Decade of Team Effectiveness Research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.A.; Smith, T.A.; Kirkman, B.L.; Griffin, R.W. The Emergence of Emergent Leadership: A Comprehensive Framework and Directions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, A.G. Heterogeneity and centrality of “dark personality” within teams, shared leadership, and team performance: A conceptual moderated-mediation model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerenza, C.N.; Marlow, S.L.; Tannenbaum, S.I.; Salas, E. Team development interventions: Evidence-based approaches for improving teamwork. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Between-Subjects Condition | Control Groups | Training Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| 1. Pre-intervention TWE | 4.85 | 0.42 | 4.72 | 0.54 |

| 2. OEC team level | 3.6 | 0.24 | 3.5 | 0.22 |

| 3. OEC Diversity | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.23 |

| 4. Post-intervention TWE | 4.8 | 0.61 | 5.1 | 0.53 |

| Predictors | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | Step 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | ||||||

| Engagement T1 | 0.327 # | 0.380 * | 0.390 * | 0.401 * | 0.401 # | 0.379 * |

| Familiarity | 0.099 | 0.185 | 0.181 | 0.280 | 0.255 | 0.076 |

| AFT | 0.345 * | 0.348 * | 0.360 * | 0.353 | 0.280 # | |

| OEC Level | 0.011 | 0.123 | 0.164 | 0.396 | ||

| OEC Diversity | 0.201 | 0.940 # | 0.976 # | 1.15 * | ||

| Two-way interaction AFT × OEC level | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.53 | |||

| AFT × OEC Diversity | −1.45 * | −1.42 # | −1.83 * | |||

| OEC Level × Diversity | 0.587 | 3.656 # | ||||

| Three-way interaction | ||||||

| AFT × OEC Level × Diversity | −6.157 * | |||||

| R2 | 0.072 | 0.156 | 0.162 | 0.236 | 0.239 | 0.321 |

| F | 1.88 | 2.96 * | 1.78 | 1.94 # | 1.692 | 2.2 * |

| ΔR2 | 0.072 | 0.085 * | 0.006 | 0.074 | 0.003 | 0.082 * |

| Practical Implications of a Short Online Affect Management Training |

|---|

For students:

|

For instructors:

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Anta, B.; Orengo, V.; Zornoza, A.; Peñarroja, V.; Gamero, N. Sustainable Virtual Teams: Promoting Well-Being through Affect Management Training and Openness to Experience Configurations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063491

González-Anta B, Orengo V, Zornoza A, Peñarroja V, Gamero N. Sustainable Virtual Teams: Promoting Well-Being through Affect Management Training and Openness to Experience Configurations. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063491

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Anta, Baltasar, Virginia Orengo, Ana Zornoza, Vicente Peñarroja, and Nuria Gamero. 2021. "Sustainable Virtual Teams: Promoting Well-Being through Affect Management Training and Openness to Experience Configurations" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063491

APA StyleGonzález-Anta, B., Orengo, V., Zornoza, A., Peñarroja, V., & Gamero, N. (2021). Sustainable Virtual Teams: Promoting Well-Being through Affect Management Training and Openness to Experience Configurations. Sustainability, 13(6), 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063491