Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of Covid-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Initiatives and Reporting in Higher Education Institutions

2.2. Previous Studies on Sustainability Reporting in Universities

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Sampling Process

3.2. Data Collection and Coding Framework

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. General Aspects of Web-Based Sustainability Reporting

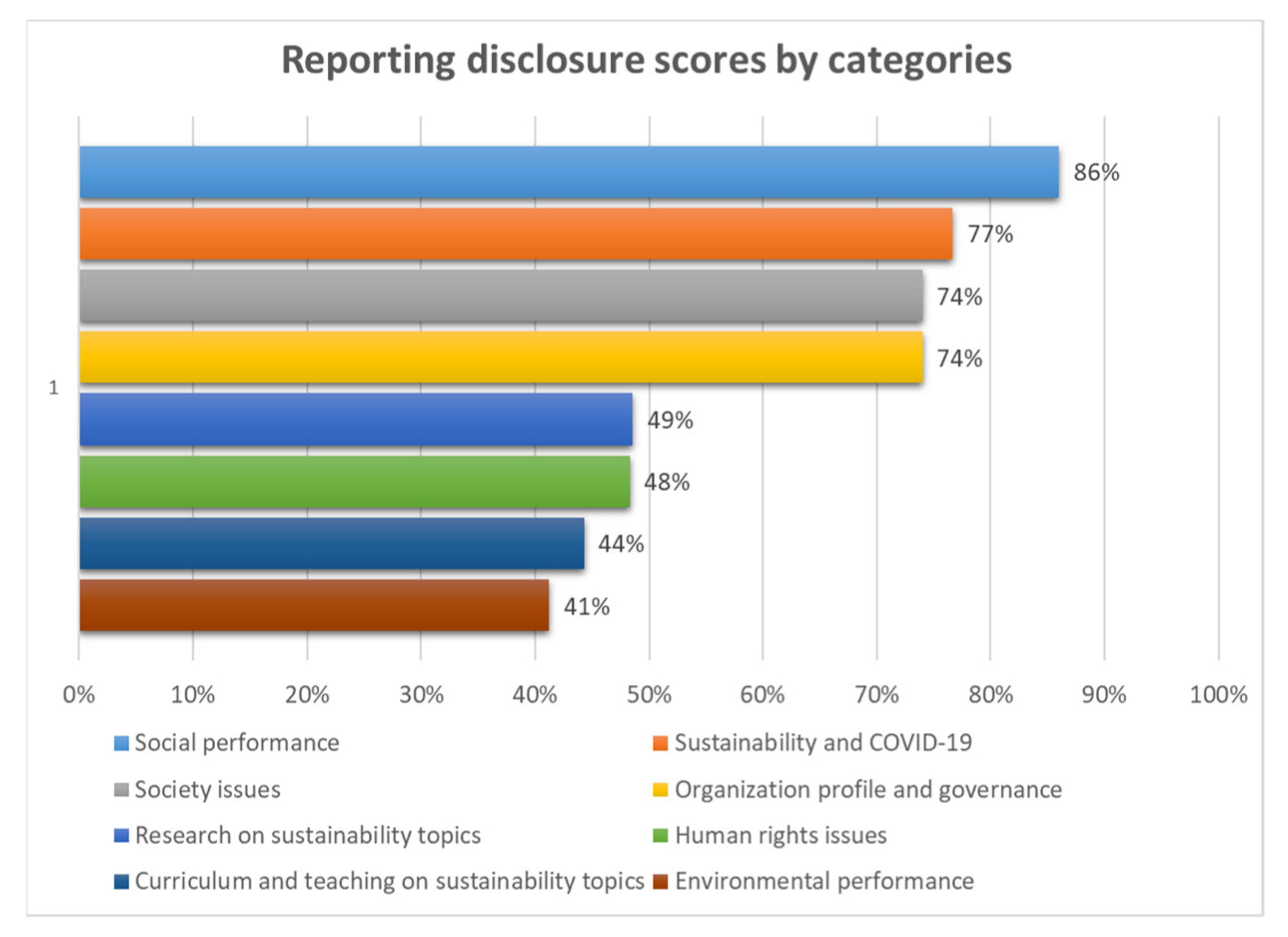

4.2. Specific Aspects of Web-Based Sustainability Reporting

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement.

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lozano, R. The state of sustainability reporting in universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrán Jorge, M.; Andrades Peña, F.J.; Herrera Madueño, J. An analysis of university sustainability reports from the GRI database: An examination of influential variables. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2019, 62, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversano, N.; Nicolò, G.; Sannino, G.; Tartaglia Polcini, P. The Integrated Plan in Italian public universities: New patterns in intellectual capital disclosure. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sordo, C.D.; Farneti, F.; Guthrie, J.; Pazzi, S.; Siboni, B. Social reports in Italian universities: Disclosures and preparers’ perspective. Meditari Account. Res. 2016, 24, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggi, S. Social and environmental reports at universities: A Habermasian view on their evolution. Acc. Forum 2019, 43, 283–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Raimo, N.; Marrone, A.; Vitolla, F. How does integrated reporting change in light of COVID-19? A Revisiting of the content of the integrated reports. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R.; Ferasso, M. The social dimensions of corporate sustainability: An integrative framework including COVID-19 insights. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Llobet, J.; Tideswell, G. Developing a university sustainability report: Experiences from the university of Leeds. In Sustainability Assessment Tools in Higher Education Institutions; Sandra Caeiro, S., Leal Filho, W., Jabbour, C., Azeiteiro, U.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, P.; Sciulli, N. Sustainability reporting by Australian universities. Aust. J. Pub. Admn. 2017, 76, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Azizi, L. Assessing sustainability reports of US universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1158–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Garde Sánchez, R.; López Hernández, A.M. Online disclosure of corporate social responsibility information in leading Anglo-American universities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 15, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Davey, H.; Harun, H.; Jin, Z.; Qiao, X.; Yu, Q. Online sustainability reporting at universities: The case of Hong Kong. Sust. Acc. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 11, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Galera, A.; de Los Ríos, A.; Ruiz, M.; Tirado, P. Transparency of Sustainability Information in Local Governments: English-Speaking and Nordic Cross-Country Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Tartaglia Polcini, P. New trends in intellectual capital reporting: Exploring online intellectual capital disclosure in Italian universities. J. Intellect. Cap. 2018, 19, 814–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Ferreira, M.R.; Lima, S. Web disclosure of institutional information in nonprofit organisations: An approach in Portuguese charities. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark 2020, 17, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Macdonald, A.; Dandy, E.; Valenti, P. The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgi, D.; Siboni, B. The disclosure of intellectual capital in italian universities: What has been done and what should be done. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Marimon, F.; Casani, F.; Rodriguez-Pomeda, J. Diffusion of sustainability reporting in universities: Current situation and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Van Liedekerke, L. Sustainability reporting in higher education: A comprehensive review of the recent literature and paths for further research. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Argento, D. Non-financial reporting formats in public sector organisations: A structured literature review. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2020, 32, 639–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboni, B.; Del Sordo, C.; Pazzi, S. Sustainability Reporting in State Universities: An Investigation of Italian Pioneering Practices. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, F.U.; Saez-Navarrete, C.; Lioi, S.R.; Marzuca, V.I. Adaptable model for assessing sustainability in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, G.; Manes-Rossi, F.; Christiaens, J.; Aversano, N. Accountability through intellectual capital disclosure in Italian Universities. J. Manag. Gov. 2020, 24, 1055–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri. Direttiva del Ministro della Funzione Pubblica Sulla Rendicontazione Sociale Nelle Amministrazioni Pubbliche. 2016. Available online: http://www.funzionepubblica.gov.it/sites/funzionepubblica.gov.it/files/16887.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- GBS. Documento di ricerca n° 7, La Rendicontazione Sociale Nelle Universita; Giuffrè Editore: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- RUS, Rete delle Università per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. 2020. Available online: https://sites.google.com/unive.it/rus/home (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Michelon, G.; Parbonetti, A. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 477–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatta, K.; Jaeschke, R. Sustainability Reporting at German and Austrian Universities. Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev. 2014, 5, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) Organization profile and governance | (5) Society issues |

| Statement from the president | Impacts on community |

| Description of the organization | Corruption |

| Governance structure or processes | Public policy |

| Commitments to external sustainability initiatives | Anti-competitive behaviour |

| Stakeholder engagement | Compliance with general legislation |

| (2) Environmental performance | (6) Research on sustainability topics |

| Material | Policies related to sustainability in research |

| Energy | Research centres/labs related to sustainability |

| Water | Sustainability-related research programs |

| Biodiversity | Incentives to sustainability research |

| Emissions, effluents and wastes | Funding and grants for sustainability research |

| Compliance with environmental legislation | Academic production related to sustainability |

| Transportation | Sustainability-related research projects |

| Environmental expenditures | |

| (3) Social performance | (7) Curriculum and teaching on sustainability topics |

| Employment | Policies related to sustainability in the curriculum |

| Labour/management relations | Courses related to sustainability |

| Occupational health and safety | Students taking sustainability-related courses |

| Training and education | Sustainability literacy assessment |

| Diversity and equal opportunity | Degree programs related to sustainability |

| Non-curricular teaching initiatives related to sustainability | |

| Scholarships offered to sustainability-related education | |

| (4) Human rights issues | (8) Sustainability and COVID-19 |

| Investment and procurement policy | Remote/online teaching activities |

| Non-discrimination | Counselling and psychological support |

| Freedom of association and collective bargaining | Prevention measures |

| Child labour and forced labour | COVID-19 Research projects |

| Security practices | Smart working |

| Indigenous rights | Crowdfunding/fundraising for COVID-19 |

| General Aspects | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of a specific section devoted to sustainability issues | 7 | 70% |

| Information regarding the presence of a specific sustainability office/committee at the university | 7 | 70% |

| Presence of a regular stand-alone social/sustainability report | 6 | 60% |

| Presence of a specific section devoted to COVID-19 issues | 6 | 60% |

| Total Items | Mean | % | Variance | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online sustainability disclosure | 49 | 29 | 59% | 24.22 | 17 (35%) | 34 (69%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicolò, G.; Aversano, N.; Sannino, G.; Tartaglia Polcini, P. Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of Covid-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063468

Nicolò G, Aversano N, Sannino G, Tartaglia Polcini P. Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of Covid-19. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063468

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicolò, Giuseppe, Natalia Aversano, Giuseppe Sannino, and Paolo Tartaglia Polcini. 2021. "Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of Covid-19" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063468

APA StyleNicolò, G., Aversano, N., Sannino, G., & Tartaglia Polcini, P. (2021). Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of Covid-19. Sustainability, 13(6), 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063468