Perceived Exposure and Acceptance Model of Appearance-Related Health Campaigns: Roles of Parents’ Healthy-Appearance Talk, Self-Objectification, and Interpersonal Conversations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. O1-S-O2-R Model

2.2. Body Image

2.3. Variables of OSOR Model

2.3.1. Orientation1-1: Parent’s Healthy-Appearance Talk

2.3.2. Orientation1-2: Self-Objectification

2.3.3. Orientation1-3: Internalization of Appearance Ideals

2.3.4. Stimulus: Perceived Exposure to Media Contents of Appearance-Related Health Campaign

2.3.5. Orientation2-1: Interpersonal Conversations and Thought Deliberation

2.3.6. Orientation2-2: Peer Pressure

2.3.7. Response(R): Attitude and Behavioral Intention

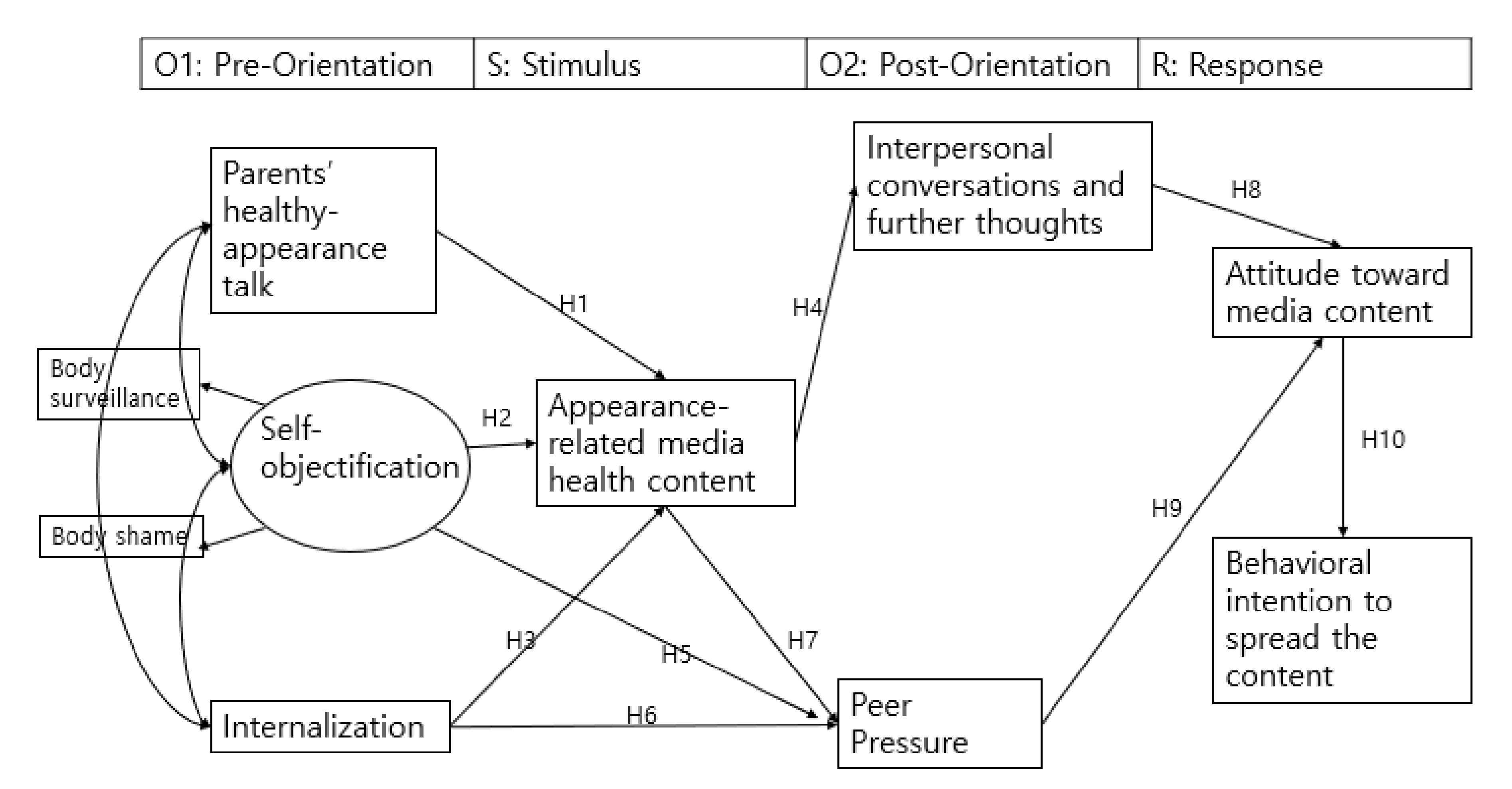

2.3.8. Proposed O1-S-O2-R Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Measures of O1-S-O2-R Variables

3.2.2. Additional Measures

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

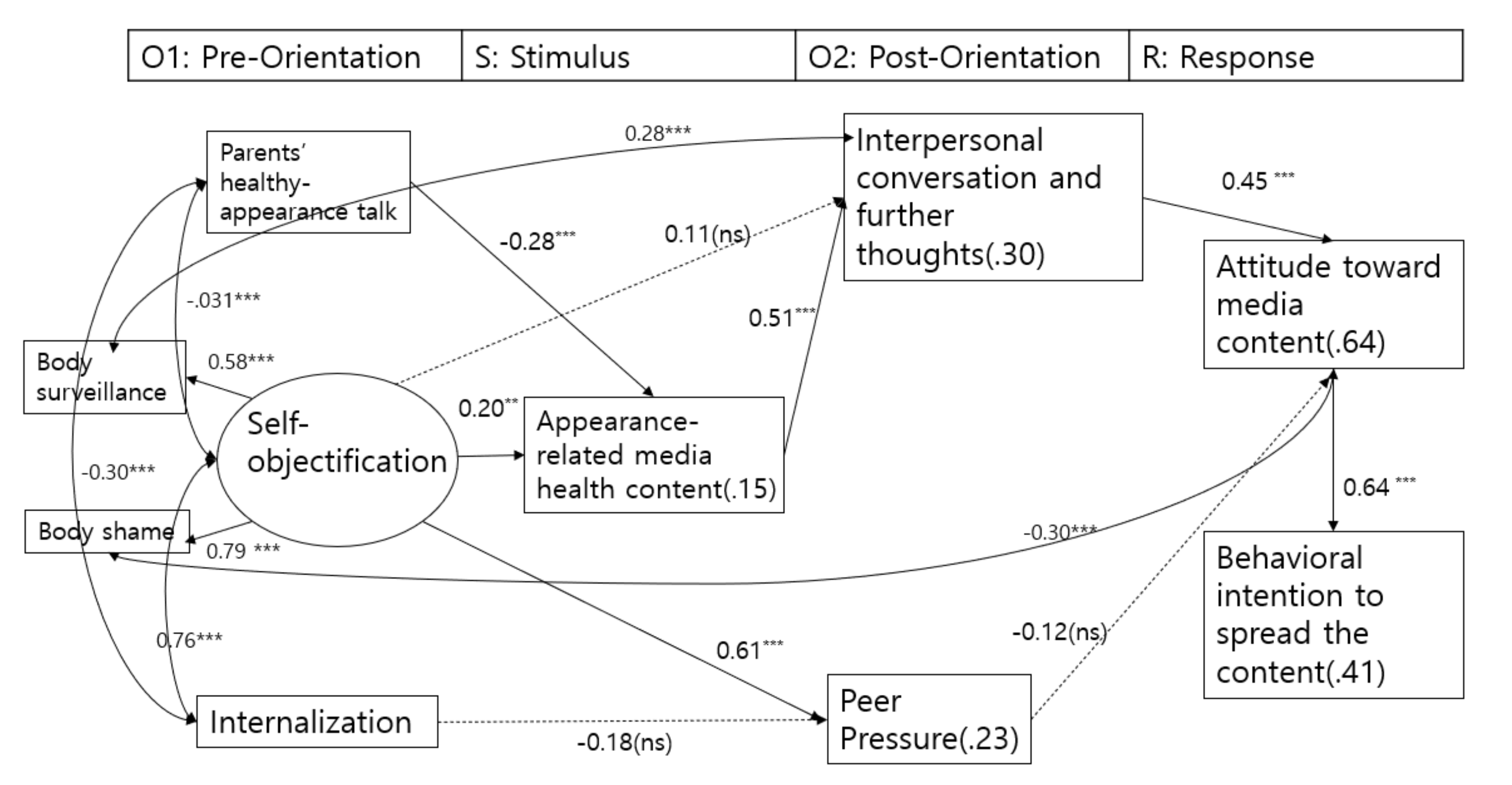

4.2. Structural Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Shin, K.; Kim, E.K. The effects of sociocultural pressures and exercise frequency on the body esteem of adolescent girls in Korea. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.K.; Schneiderman, J.U.; Winter, V.R. Association of body weight perception and unhealthy weight control behaviors in adolescence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K. Sociocultural appearance standards and risk factors for eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; McLean, S.A.; Marques, M.; Dunstan, C.J.; Paxton, S.J. Trajectories of body dissatisfaction and dietary restriction in early adolescent girls: A latent class growth analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1664–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Forbes, G.B. Multidimensional assessment of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in Korean and U.S. college women: A comparative study. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Seo, Y.S.; Baek, K.Y. Face consciousness among South Korean women: A culture-specific extension of objectification theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2016-ISAPS-Results-1.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- You, S.; Shin, K. Body esteem among Korean adolescent boys and girls. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. The interplay between media use and interpersonal communication in the context of healthy lifestyle behaviors: Reinforcing or substituting? Mass Commun. Soc. 2010, 13, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K. The communications revolution and cancer control. Nat. Rev. 2005, 5, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimal, R.N.; Flora, J.A.; Schooler, C. Achieving improvements in overall health orientation: Effects of campaign exposure, information seeking, and health media use. Commun. Res. 1999, 26, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Matsaganis, M.D. How interpersonal communication mediates the relationship of multichannel communication connections to health-enhancing and health-threatening behaviors. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1002–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.G.; Wang, Z.; Kulpavarapos, S. Testing Direct and Indirect Effects of Identity, Media Use, Cognitions, and Conversations on Self-Reported Physical Activity Among a Sample of Hispanic Adults. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, A.; Segrin, C.; Harwood, J. Appearance-related communication mediates the link between self-objectification and health and well-being outcomes. Hum. Commun. Res. 2014, 40, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H. Mechanisms through which adolescents attend and respond to anti-smoking media campaigns. J. Commun. 2008, 58, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H. No clear winner: Effects of the biggest loser on the stigmatization of obese persons. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Tian, Y. Effects of entertainment (mis)education: Exposure to entertainment television programs and organ donation intention. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E. The effects of family communication and media exposure on high school girls’ cosmetic surgery intentions: An exploratory study on the mediating effect of the behavior of appearance internalization, appearance satisfaction, information seeking behavior. Korean J. Broadcasting Telecommun. Stud. 2019, 33, 140–183. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.; Zajonc, R.B. The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lindzey, G., Aronson, E., Eds.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 137–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.A. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173.e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; van den Berg, P.; Roehrig, M.; Guarda, A.; Heinberg, L. The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M. Television and adolescent body image: The role of program content and viewing motivation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Tiggemann, M. Sociocultural and individual psychological predictors of body image in young girls: A prospective study. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.C.; Vigfusdottir, T.H.; Lee, Y. Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: An examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, J.M.; Kosicki, G.M.; McLeod, D.M. The expanding boundaries of political communication effects. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research; Bryant, J., Zillman, D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 123–162. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, D.M.; Kosicki, G.M.; McLeod, J.M. Resurveying the boundaries of political communications effects. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Bryant, J., Zillman, D., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 215–267. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, J.M.; Scheufele, D.A.; Moy, P. Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Commun. 1999, 16, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental concern patterns of television viewing, and pro-environmental behavior: Integrating models of media consumption effect. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Robinson, J.D. Media complementarity and health information seeking in Puerto Rico. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keery, H.; van den Berg, P.; Thompson, J.K. An evaluation of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating with adolescent girls. Body Image 2004, 1, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzeo, S.; Trace, S.; Mitchell, K. Effects of a reality T.V. cosmetic surgery makeover program on disordered eating attitudes and behavior. Eat. Behav. 2007, 8, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.E.; Sperry, S.L.; Small, B.; Thompson, J.K.; Sarwer, D.B.; Cash, T.F. Internalization of appearance ideals and cosmetic surgery attitudes: A test of the tripartite influence model of body image. Sex Roles 2011, 65, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, H.; Thompson, J.K. The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with adolescent girls. Body Image 2006, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.; Thompson, J.K.; Brandon, K.; Coovert, M. The tripartite model of body image and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, E.; Dittmar, H. Associations between appearance-related self-discrepancies and young women’s and men’s affect, body satisfaction, and emotional eating: A comparison of fixed-item and participant-generated self-discrepancies. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, H.; Naumann, U.; Treasure, J.; Schmidt, U. Is fat talking a causal risk factor for body dissatisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichter, M. Fat Talk: What Girls and Their Parents Say about Dieting; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Loth, K.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Croll, J.K. Informing family approaches to eating disorder prevention: Perspectives of those who have been there. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2009, 42, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, A.; Mills, J.S. Correlates, causes, and consequences of fat talk: A review. Body Image 2015, 15, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, L.E.; Martz, D.M.; Bazzini, D.G.; Curtin, L.A.; Lea, S.A. Fat talk and self-presentation of body image: Is there a social norm for women to self-degrade? Body Image 2006, 3, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martz, D.M.; Petroff, A.B.; Curtin, L.A.; Bazzini, D.G. Gender differences in fat talk among American adults: Results from the psychology of size survey. Sex Roles 2009, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.B.; Rogers, C.B.; Etzel, L.; Padro, M.P. “Mom, quit fat talking—I’m trying to eat (mindfully) here!”: Evaluating a sociocultural model of family fat talk, positive body image, and mindful eating in college women. Appetite 2018, 126, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Augustus-Horvath, C.L.; Tylka, T.L. The acceptance model of intuitive eating: A comparison of women in emerging adulthood, early adulthood, and middle adulthood. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Dirks, D.; Matteson, A. Roles of sexual objectification experiences and internalization of standards of beauty in eating disorder symptomatology: An examination and extension of objectification theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaymat, L.D.; Moradi, B.U.S. Muslim women and body image: Links among objectification theory constructs and the hijab. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissell, K.; Rask, A. Real women on Real Beauty: Self-discrepancy, internalization of the thin ideal, and perceptions of attractiveness and thinness in Dove’s campaign for Real Beauty. Int. J. Advert. 2010, 29, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J. Performing beauty: Dove’s ‘Real Beauty’ campaign. Symb. Interact. 2009, 22, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.D.; Yang, L. The role of implicit theories in evaluations of ‘Plus-Size’ advertising. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y.; Chen, H.; He, L. Consumer responses to Femvertising: A dat-mining case of Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty” on YouTube. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.; Albarracin, D.; Eagly, A.; Brechan, I.; Lindberg, M.; Merrill, L. Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 555–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, R. Causes and effects of causal attribution. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, R.; Kumar, A.P. Person memory: Personality traits as organizing principles in memory for behaviors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangor, C.; McMillan, D. Memory for expectancy-congruent and expectancy-incongruent information: A review of the social and social developmental literatures. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, R.; Yanovitsky, I. Using theory to design evaluations of communication campaigns: The case of the national youth anti-drug media campaign. Commun. Theory 2003, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sotirovic, M.; McLeod, J.M. Values, communication behavior, and political participation. Political Commun. 2001, 18, 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, B.G.; Yzer, M.C. The roles of interpersonal communication in mass media campaigns. In Communication Yearbook; Beck, C., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 31, pp. 420–462. [Google Scholar]

- van den Putte, B.; Yzer, M.; Southwell, B.G.; de Brujin, G.J.; Willemsen, M.C. Interpersonal communication as an indirect pathway for the effect of anti-smoking media content on smoking cessation. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Gotlieb, M.R.; Nah, S.; McLeod, D.M. Applying a cognitive-processing model to presidential debate effects: Post debate news analysis and primed reflection. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Self-concept from middle childhood through adolescence. In Psychological Prospective on the Self; Suls, J., Greenwald, A.G., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gondoli, D.M.; Corning, A.F.; Salafia EH, B.; Bucchianeri, M.M.; Fitzsimmons, E.E. Heterosocial involvement, peer pressure for thinness, and body dissatisfaction among young adolescent girls. Body Image 2011, 8, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Winegard, B.; Winegard, B.M. Who is the fairest one of all? How evolution guides peer and media influences on female body dissatisfaction. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trekels, J.; Eggermont, S. Beauty is good: The appearance culture, the internalization of appearance ideals, and dysfunctional appearance beliefs among tweens. Hum. Commun. Res. 2017, 43, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M.C.; Davis, K.C.; Haviland, M.L.; Healton, C.G.; Messeri, P. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between “truth” anti-smoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, M.; Biener, L. The impact of an anti-smoking media campaign on progression to established smoking: Results of a longitudinal youth study. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McKinley, N.; Hyde, J. The Objectified Body Consciousness scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Women Q. 1996, 20, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B. Addressing gender and cultural diversity in body image: Objectification theory as a framework for integrating theories and grounding research. Sex Roles 2010, 63, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluck, A.S. Family influence on disordered eating: The role of body image dissatisfaction. Body Image 2010, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R. Body image: Familial influences. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance; Cash, T.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, R.; Chabrol, H. Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: A review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2009, 17, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.P.; Smolak, L. Recent developments and promising directions in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating in children and adolescents. In Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth: Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment, 2nd ed.; Smolak, L., Thompson, J.K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, H.K.; Paxton, S.J.; Wertheim, E.H. Investigation of body comparison among adolescent girls. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 1906–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Cattarin, J.; Fowler, B.; Fisher, E. The Perception of Teasing Scale (POTS): A revision and extension of the Physical Appearance Related Teasing Scale (PARTS). J. Personal. Assess. 1995, 65, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Year in college | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Sex | 0.19 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Parents’ talk | −0.20 ** | −0.06 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Body surveillance | 0.03 | 0.15 * | −0.05 | 1 | |||||||

| 5. Body shame | 0.05 | 0.17 * | −0.31 *** | 0.46 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. Internalization | 0.16 * | 0.44 *** | −0.30 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.61 *** | 1 | |||||

| 7. Exposure to campaign a | 0.25 *** | 0.32 *** | −0.34 *** | 0.14 * | 0.26 *** | 0.20 ** | 1 | ||||

| 8. Conversation | 0.18 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.24 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.17 * | 0.22 ** | 0.53 *** | 1 | |||

| 9. Peer pressure | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.17 * | 0.36 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.14 * | 0.20 ** | 1 | ||

| 10. Attitude | 0.07 | 0.23 ** | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.32 *** | 0.44 *** | −0.01 | 1 | |

| 11. Behavioral Intention | −0.11 | 0.19 ** | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.29 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.03 | 0.64 *** | 1 |

| M | 2.29 | 1.36 | 4.05 | 3.28 | 2.25 | 2.56 | 18.45 | 2.52 | 2.85 | 3.41 | 3.13 |

| SD | 1.10 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 5.79 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.92 |

| alpha | - | - | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.85 | - |

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exposure to anti-lookism content | 1.79 | 0.69 | 1~4 |

| 2. Exposure to diversity in beauty standards | 2.06 | 0.87 | 1~4 |

| 3. Exposure to problems in excessive focus on the look | 2.18 | 0.79 | 1~4 |

| 4. Exposure to Body Positive campaign | 1.46 | 0.69 | 1~4 |

| 5. Exposure to a Real Beauty campaign | 1.30 | 0.59 | 1~4 |

| 6. Exposure to No Fat Talk campaign | 1.36 | 0.67 | 1~4 |

| 7. Exposure to Corset-Free movement | 2.16 | 0.93 | 1~4 |

| 8. Exposure to Plus Size model movement | 1.76 | 0.96 | 1~4 |

| 9. Exposure to banning makeover shows on air | 1.51 | 0.74 | 1~4 |

| 10. Exposure to banning beauty contests on air | 1.51 | 0.75 | 1~4 |

| 11. Exposure to official appearance guideline on air | 1.35 | 0.65 | 1~4 |

| Change in time spent with parents after COVID-19 | 3.41 | 1.00 | 1~5 |

| Change in time spent with friends after COVID-19 | 2.66 | 1.07 | 1~5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, E.; Lee, G.-i. Perceived Exposure and Acceptance Model of Appearance-Related Health Campaigns: Roles of Parents’ Healthy-Appearance Talk, Self-Objectification, and Interpersonal Conversations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063445

Lee E, Lee G-i. Perceived Exposure and Acceptance Model of Appearance-Related Health Campaigns: Roles of Parents’ Healthy-Appearance Talk, Self-Objectification, and Interpersonal Conversations. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063445

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Eunsoon, and Gyu-il Lee. 2021. "Perceived Exposure and Acceptance Model of Appearance-Related Health Campaigns: Roles of Parents’ Healthy-Appearance Talk, Self-Objectification, and Interpersonal Conversations" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063445

APA StyleLee, E., & Lee, G.-i. (2021). Perceived Exposure and Acceptance Model of Appearance-Related Health Campaigns: Roles of Parents’ Healthy-Appearance Talk, Self-Objectification, and Interpersonal Conversations. Sustainability, 13(6), 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063445