Abstract

Energy reforms play an essential role in technological change as they aim to contribute to an open market: costs reduction, competitiveness, and technology development. This article seeks to assess the impact and effect of reforms on the energy sector. The article’s objective is to evaluate the process of deregulation policies and their micro and macroeconomic effects on the energy sector, and specifically on electricity, by analyzing literature related to electricity reforms. Further, the article intends to explore the impacts of deregulation on power pricing, power market, electricity accessibility, innovation, and competitiveness. Another objective of the article is to analyze the role played by various stakeholders in the deregulation policies, including the government, national entities like states, the private sector, and consumers. The article identified ways to improve the economic impacts of deregulation policies in the energy sector. After a systemic review of specialized articles regarding their theoretical approach, results showed a positive relationship between reform and innovation, competitiveness, opening-up of the market, technology, and price changes. Although deregulation measures aimed to reduce the consumers’ electricity cost, the changes in power prices were achievable only in the long-term and not in the short-term. Additionally, government regulators and stakeholders participated in implementing various measures to ensure that deregulation achieved its primary objective of reducing power prices. Such efforts include developing divestiture policies and implementing rate cuts.

1. Introduction

Electricity industries in most countries have been government-controlled and government-regulated. According to Urpelainen [1], this has created vertically integrated utilities (VIUs), which means that the government handles electricity from generation to transmission and later to the distribution channels. Historically, numerous regulations have been implemented in the energy sector to foster competitiveness (availability of customers due to multiple companies operating in the business environment, which has a significant link with the well-being of the economy), ensure compliance with the set standards, and increased regulation with various stakeholders in the sector. Regulations aim to positively impact the energy sector, aiming to transform the economy by creating more opportunities for private-company participation. On the other hand, deregulation refers to eliminating or substantially changing state-level policies in the industry, reducing government supervision and industry players’ control. Over the last three decades, national and regional governments have strived to implement deregulation in the energy sector, reduce prices of commodities like electricity and enhance competitiveness in the industry, and averting the challenges brought about by regulation [2].

Throughout this time, the impact of deregulation in the energy sector has been a matter of debate, as some studies have produced different results. Studies that have supported deregulation have created more opportunities for potential investors, thereby enhancing electricity’s competitiveness and affordability. Researchers who have argued against deregulation have put forward various facts, including the lack of compensation for utilities and business pursuits, that were undertaken during the regulation periods [3]. For instance, some companies invested funds in nuclear power plants and costly long-term contracts in the oil, coal, and electricity sectors to believe that their investments were secured by various regulations that existed at the time. However, after deregulation, the investors feared that their investments would be in jeopardy [4].

In general terms, the electricity industry has three main functions: generation, transmission, and distribution of electric power [5]. Historically, a single firm, primarily a government entity, was given the mandate to oversee all three functions: Historically, a single firm, primarily a government entity, was provided to manage all three tasks for residential and business entities. However, industry players observed that the entity created under the monopoly market has adversely affected the price of electric power, and quality service, and competitiveness since consumers have limited options to select suppliers [6].

As Rudnick [7] demonstrated, differing international electricity rates pushed some regions to begin the process of deregulating the electricity industry to compete with competitive prices and attract investment. For instance, regulations have fostered different average electricity rates in the United States prices in the Northeast, which are higher than 50% of the national average, while the Midwest and Northwest rates are much below the national average [8]. Deregulating the electricity sector has also been propelled by advances in technology, which have eliminated the benefits traditionally attributed to large monopoly suppliers and created an opportunity for smaller firms to compete. The regulation involves various stakeholders who play an essential role in the economy, including government entities, the private sector, market regulators, and consumers.

Technology is a significant aspect of deregulation measures. It has played a significant role in enhancing deregulation efforts. When the electricity industry drifts from being a monopoly, entities operating in the sector could become more motivated to protect their markets. One of the strategies utilized by entities is to embrace technology, thereby improving customer satisfaction. For example, entities in the electricity industry have adopted flexible, change-oriented computer systems. The adoption of new technologies has impacted the economy, reducing operational and utility costs. The firms have also developed enhanced tailored billing systems and real-time pricing of electric power. Some companies have adopted Utility Translation Systems software to obtain consumption data from massive power customers [9].

Reforms have been pushed through, using different methods. For instance, since 1990, most developed countries began to create reforms that focused on the market-oriented power sector. For instance, according to some studies [10,11,12], reforms included total privatization transfer of business entities or activities, from the public to private ownership innovation (technology-based changes aimed at either changing or improving the delivery of services to customers), restructuring some market regulations (business environment whereby interested parties, like investors, can easily enter or leave the market), and restructuring electricity prices. Each of the scenarios had significant impacts on the adopting countries, hence becoming case studies for other nations, adapting them to their context. Market regulations as a method of energy reform are the most common approach globally, as most countries, especially those still developing, create quasi-monitoring of service quality [13].

Privatization led to the widespread adoption of the Independent Power Project (IPP) [14]. For instance, a study by Zhang [10] suggests that IPPs have resulted in over 40% of energy production in most countries. However, the study shows that privatization of power distribution has become more challenging for both established and emerging economies. Rosillo-Calle [15] elucidate that most privatized firms experience high-efficiency levels, and their performance is kept in check by the more efficient public utilities due to the management of private services which have better governance as well as management practices, such as transparent financial reporting, meritocratic self-selection, and modern I.T. systems. The notion of government has been one of the core models of political science, political geography, and public policy over the last two decades. Governance is an ongoing pattern of social relations between actors that involve intentional interaction and attempts to organize these interactions [16].

Restructuring of the energy sector is another method utilized by most countries. Countries that utilize restructuring methods, such as India, tend to operate using vertically integrated power utilities of the state, thus monopolizing the power market [17]. Other countries use vertical and horizontal approaches, where various companies do the generation and supply of power. Completion is also used in other countries by introducing wholesale power markets, enabling energy generators to sell the power to a wide range of customers [18]. Nations that utilize competition as a reform strategy benefit from the efficiency gained from efficient generation resource distribution; however, they need the introduction of better incentives that ensure new capacity investment [14]. Other countries do not find it easy to follow this approach due to the requirements to have structural, financial, and regulatory preconditions for markets in the energy sector.

Power sector reforms have resulted in several benefits to the economy of most nations. According to Nagayama [18], power sector reforms successfully delivered low electricity tariffs and increased private investments. On the other hand, Nair [11] asserts that governance standards play a crucial part in reformulating the energy sector. Such reforms have significant impacts on the selected parameters of the energy sector. According to Ogunleye [19], national and regional structures vary widely, and the energy transitions indicate complex systems, incumbent officeholders, and political dynamics. Policies have been fundamental in the energy sector. For example, renewable energy has been supported not only to complement energy matrices and manage environmental concerns in the development and sustainability industry [20]. Sustainable development is becoming increasingly relevant as a condition for human life, a foundation for successful human development. It plays a key role when solving the social, economic, and environmental issues impacting human and natural systems [21].

The case of Nigeria’s energy reform reveals stakeholders’ significant participation in the country’s regulatory, institutional, legislative, and fiscal aspects [19]. Following the most recent reforms in the energy sector, the Mexican energy transition shows that reforms play a crucial role in the success of energy security and climate change mitigation; there is increasing evidence that climate change will strongly affect people worldwide [22]. The two contributions generated from the two reforms underscore the political economy trade-offs that exist between short-term low electricity tariffs resulting from political and economic benefits and the desire to attain a strong climate commitment [19].

Other regions have used various forms of regulation and energy control. For instance, in California, the government insisted on refraining from creating more energy production plants and concentrating on creating platforms to increase renewable energy and put in measures to conserve electricity [8]. The implications of such reforms indicate that a country specialized in alternative forms of energy could meet its energy demands. According to Orion [8], such approaches work where the state bodies produce sufficient energy to run homes and industries. Most economies may find this approach difficult as it implies that countries must approach energy production from several perspectives. It requires expertise, sometimes resulting in outsourcing services from other countries.

However, the economic effect of the deregulation of the energy sector on electricity remains largely under-studied. For this reason, the current research involves a systematic review aiming to analyze various research studies that have been developed to evaluate the economic impact of deregulation policies in the energy sector and specifically on electricity. Analysis methods are often chosen based on their appropriateness concerning a research topic and theoretical framework [23]. To achieve the research aim, the objectives of the research are the following:

- To analyze the literature that is allied to the electricity reform;

- To review the process of deregulation policies and their micro and macroeconomic impact on the energy sector and specifically on electricity;

- To explore the impacts of deregulation on power pricing, power market, electricity accessibility, innovation, and competitiveness;

- To analyze various stakeholders’ role in the deregulation policies, including the government, national entities like states, private sector, and consumers;

- To identify ways to improve the economic impacts of deregulation policies in the energy sector.

The study included a systematic review of 35 qualitative and quantitative articles. Thereby, it accumulated sufficient evidence to support or reject the notion that deregulation has transformed electricity’s affordability and accessibility. The main concepts, theories, and results were critically analyzed under standardized effects that relied on evidence.

The article has identified regulation impacts in the energy sector, as reported in the studies, and its effects on electricity. The current review developed a new theory related to the deregulation of electricity in terms of prices, innovation, and competitiveness through systematic assessment and analysis of results obtained from various sources.

This paper is divided into four sections: The Section 1 presents the introduction and focus of invention. The Section 2 shows the methodology: study, search, and selection. As well as the characterization of studies. The Section 3 presents results, including the main findings on deregulation effects. Finally, the Section 4 presents conclusions.

Focus of Intervention

A look at the global reforms in the energy sector reveals the use of both hybrid and textbook reforms [1]. These two types of reforms have been in use for years and continue to work in current reforms. Urpelainen [1] asserts that developing countries have mainly considered the use of these reforms that lead to the adoption of the hybrid power sector “while often eschewing privatization and liberalization of competition” [20]. Even though the approaches differ from one country to another, the intended goals are usually similar. They are controlled by the global demand for power, sectoral usage, and international regulations on energy use and their effects on climate change and global warming.

Different governments argue that their public enterprises are constructed to provide the necessary power since electricity production and supply are a national responsibility. They consider competition reforms to be both wasteful and dangerous to the country’s economy. According to Zhang [12], this argument relies heavily on the idea that electricity evolved from being a good that can only be used in mining, manufacturing, and heavy-duty operations, the most crucial catalysts in the current economic growth. Such nations claimed that power is too essential to be left in private suppliers’ hands, whose business lies entirely in profit generation. Even the countries that allow privatization in the energy sector make efforts to control the existing companies. Nations that consider government monopoly as the best approach to improve service in the power arena also believe that such strategies enhance the economy’s scale and scope.

Nations that have implemented energy reforms to open the market to the private sector set regulatory measures to ensure that companies take advantage of competitiveness to transform the industry dynamic. Governments have also set energy regulatory commissions that ensure that they maintain a range of product prices that comply with state laws. However, according to Songvilay [24], in most energy reforms, governments have not set essential measures such as constructing state-owned facilities to ensure that the country remains powered even if the private firms fail in meeting energy demands.

Historically hydrocarbon and carbon plants were unique sources in the energy production sector. Over time, many other sources have emerged to meet the country’s demand and export it to other consumer countries. New processes and operations occurred to manage the energy sector to make it efficient. Technology has had several impacts on this process to support energy sector reforms. The technologies currently used in the production of energy have also resulted in the electricity cost (costs incurred by customers, either household or companies, like connection charges) decreasing because of economies of scale, which implies that “whatever inefficiencies existed in the state-controlled model of power could be obscured by declining total costs” [25]. The result of the reduction in energy prices led to consumers expecting a decline. However, other countries did not immediately increase their power production with improved technology despite technology development. Still, they continued with the older methods, so the production method results vary from one country to another. Most developed countries moved away from fossil fuels, used nuclear energy, and are now adopting renewable energy. Whereas some developing countries are still dependent on fossil fuels, others have moved to hydroelectric power generation plants, but a few cases are fostering renewable energy [26]. Additionally, fossil fuels and macroeconomic shocks that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s led to the formulation of other significant policies, reforms, and investments in the energy sector to avoid national energy operations and economic stability impacts [27].

2. Methodology: Study, Search, and Selection Criteria

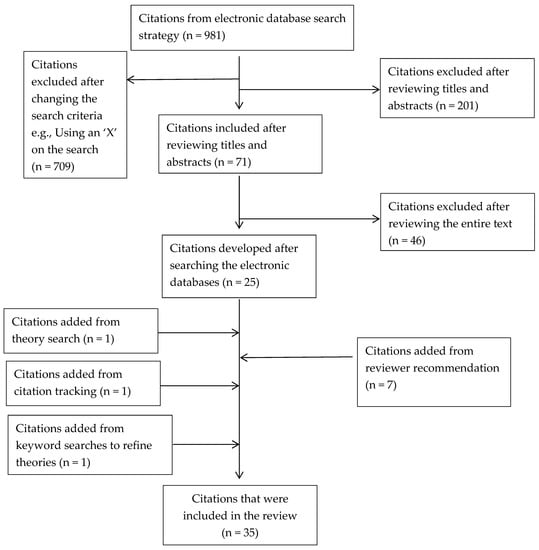

The following section explains how this research used inclusion and exclusion selection criteria. Throughout the elaboration process, reviewers provided important feedback to enhance the results of the findings. A systematic and comprehensive search was conducted to identify literature studies published between the years 1999 and 2021. Throughout a first search, a total of 981 citations were obtained from seven international databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, WorldWideScience, science.gov, Education Resource Information Centre, ResearchGate, and the Web of Science, WoS (in which Journal STORage (JSTOR), Sciencedirect.com, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and many other databases intersect). The search criteria were adjusted to eliminate various studies not related to the current research; Various keywords were selected to collect all the required materials. The keywords included, among others, “deregulation”, “reform”, “electricity sector” “electricity sub-sector”, “electricity regulation in X country”, “electricity regulation in developed countries”, “electricity regulation in developing countries”, “electricity deregulation in X region”, “electricity regulation in X region”, “effects of deregulation”, “deregulation of energy sector and cost of power”, “deregulation and cost of electricity”, and “energy sector deregulation”, among others. Based on reviewers’ feedback, the systematic review included important search criteria such as coverage of the whole electricity sector or sub-sector, and narrowing the search to developed countries, and developing countries.

After refining the keywords search criteria, 709 studies were removed, which resulted in 272 significant studies. Multiple titles and abstracts were then reviewed from these sources, after which 201 resources were excluded from the research since they were considered unrelated to the current research. A total of 71 studies were found to be significant after analyzing only the titles and abstracts; those studies were then entirely examined, whereby 25 reviews were found to be substantial and related directly to the issue under consideration. Lastly, the research was enriched with ten more studies gathered as follows: One study was obtained from the theory search, another one was obtained from citation tracking, one more study was found from keyword searches to refine theories, and seven studies were obtained from a reviewer recommendation. Therefore, this Literature Review includes a total of 35 studies. Figure 1 shows the study collection model. Based on reviewers’ feedback, the study collection model was updated to better understand the methodology process and offer comprehensive findings.

Figure 1.

Study collection model.

2.1. Analysis Criteria

This article considers specific indicators that were searched amongst the evidence that involved various types of study designs and methods through a literature review. Table 1 summarizes the study analysis criteria.

Table 1.

Analysis criteria.

2.2. Characterization of Studies

A synthesis of studies conducted three decades ago suggests that some countries with a different focus of intervention and different implementation mechanisms have made significant progress in their energy provisions. In contrast, others have not made notable progress. The analyzed articles are from various regions across the world and were included in the sample regardless of the location considered for deregulation. For example, some studies considered countries in Asia while others thought the energy sector in European countries or the Americas. Some countries were found to have one or two entities that controlled the generation and distribution of electric power; hence limited studies could be derived from such countries. Some studies focused on smaller territories; therefore, results could not be generalized since they did not cover a wider geographical area.

The studies obtained data and information from multiple sources, including secondary sources and interviews, to examine how deregulation policies have been implemented in various countries and regions, including policies that have taken place in the past or are currently underway. Most of the studies were focused on deregulation policies and their influence on the electricity industry in terms of power pricing, connectivity, liberalism, innovation, and competitiveness. The studies also included the role played by various stakeholders in the power industry, including the government, national entities like states, the private sector, and consumers.

For instance, Chong [28] focused on regions, while Kayo [29] focused on specific areas. Including several studies eliminated biases and enabled the study to have different perspectives. Additionally, studies either focused on a single variable of interest or multiple elements. For example, Zhang [12] focused on the effects of deregulation on various factors, including competition, privatization, and the cost of electricity. Additionally, other studies considered targeted innovations and policies implemented by governments, market regulators, or systems. For example, Nepal [30] focused on industry reforms, while other studies [11,13,14,20] focused on government policies and reforms.

3. Results

Table 2 provides a summary of the results found in this study. For more information about the articles, please refer to Appendix A.

Table 2.

Summary results (in alphabetical order).

3.1. Main Findings on Deregulation Effects

Electric utilities have been regulated in most parts of the world since early times. For example, when the Great Depression occurred, holding companies operated and controlled a large industry proportion. When banks decided to recall the loans granted to these holding companies, the companies were forced into a crisis, thereby leading to a financial collapse in the industry. Companies operating in the sector ran into losses, and the value of their shares decreased drastically. Numerous investors worldwide made enormous losses despite the belief that investment in the energy sector was safe [31]. The losses hurt the economies of major countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Due to the disastrous effects of an unregulated market, some countries decided to regulate their energy sectors. A subsequent example of this kind of regulation is the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1993 in the United States [32]. Regulations played a crucial role in preventing a crisis that could arise in the vital energy sector, thereby safeguarding the economy. Some regulations limited companies operating in the industry to cover only a country, state, or region.

Additionally, the policies limit the amount of debt that a company operating in the industry could take, thereby ensuring that companies have a high liquidity ratio, thus protecting investors’ funds [33]. Before the rules were implemented, power and decision-making were concentrated on a few companies that used the utilities to finance risk investments. However, the laws and policies implemented reduced the concentration of power from those few companies and distributed it to more companies, reducing the overall risk. For example, in the United States, the Federal Power Commission (FPC) was created to develop interstate electricity transmission and stipulate electricity’s wholesale price [32]. State entities acted on the powers newly bestowed on them by developing utility commissions and creating price controls on electricity prices. Entities worldwide are given the power to control electricity’s price to produce electricity and earn a utility profit. Therefore, the electricity price was not based on demand and supply for other commodities but structured by relevant entities.

Since the price of electricity was directly proportional to costs incurred during production (including oil prices), a spike in generation meant increased electricity rates. In the 1970s, oil prices increased sharply, thereby raising electricity prices to unaffordable levels. The drastic increase in electricity prices harmed the economy as it resulted in a rise in inflation levels. Since the 1990s, various countries have implemented deregulation procedures to reduce electricity prices, thereby making power more affordable for most citizens. For example, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FPC) has developed policies that allowed deregulation to occur in the United States [32].

Most studies acknowledged that deregulation aimed to increase competition in the industry and reduce the price of electricity. The studies considered put forward various explanations to express ideas regarding the effects of deregulation.

The growth of the IPPs revolutionized the industry by creating aggressive competition that goes to the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) to manage state-owned companies, thereby ensuring that they compete favorably with private entities [11]. Deregulation has also created a suitable opportunity for investors to fund companies operating in the power sector [34]. The increased funding has also boosted firms that operate in the industry, thereby stimulating growth and competitiveness. To survive and thrive in the industry, companies are forced to focus not only on profits but also on customer service quality.

Secondly, deregulation policies implemented in the energy sector have expanded the power industry [35]. Previously, an increase in coal prices or oil prices adversely affected the price of electricity. When companies controlled the industry, the electricity price relied on production costs, which included fuel costs. However, it resulted in the introduction of more competitive companies with some production costs to ensure their competitiveness since pushing the consumers’ incremental cost would adversely affect such competitiveness. Over 80% of electricity in the world is obtained from coal, thus an increase in coal prices is likely to lead to an increase in the cost of electricity [36]. Deregulation has created an opportunity for companies operating in the energy sector to access subsidized coal under the old ‘plan’ prices. Additionally, companies have also been encouraged to substitute coal, thereby limiting their over-reliance on it. Diversification from coal has also expanded the sector, thus creating more investment opportunities.

Deregulation has led to the separation of various stages of power generation and distribution, thereby creating avenues where entities operating in the industry can leverage and develop new and advanced strategies to enhance the process’s implementation at various stages. For example, France has liberalized its electricity sector by removing the state company Électricité de France (EDF)’s monopoly rights, thereby meeting the requirements of the E.U. directives [1]. Additionally, the French government’s direct involvement in energy companies has decreased over time, thereby creating an opportunity for private companies to invest in the industry. This has triggered private companies to develop innovative ideas to increase their market share and enhance their sustainability in the industry. Therefore, deregulation has a positive impact on innovativeness as it triggers entities operating in the industry to develop differentiated strategies to thrive.

3.2. Stakeholders’ Role in the Deregulation

Most studies acknowledge that deregulation is an effective method of achieving low electricity prices. However, the reduced prices can only be fulfilled if two conditions are met. First, lower power prices can be accomplished in the long run and not in the short term [14]. After the changes are implemented, industry players must be transformed to accommodate the adjustments, taking a longer time than expected. Secondly, reduced electricity prices because of deregulation can be achieved if state regulators resolve institutional issues that hinder creating a competitive retail electricity market.

Various studies have pointed out different factors that would hinder the creation of a competitive power market. First, the governments must develop strategies that would compensate industry players for the utilities for any profitable business they venture into [18]. Previously, firms with monopolistic powers in the electricity sector were financially stable, so the production cost fluctuations were not significant enough to drive the entities out of business. However, the introduction of numerous entities increases competition and creates risks associated with unprofitable business pursuits. Therefore, the government should be willing to stipulate investors’ measures in case of costly business ventures [37]. In a state-regulated monopoly system, the entities would charge customers higher fees to recover any amount lost due to unprofitable businesses. However, under the deregulated market, such companies cannot increase fees since it would decrease their competitiveness.

According to Nagayama [14], one possible reason for improvement includes introducing independent power producers (IPPs), the creation of regulatory agencies, the generation and transmission unbundling, and the introduction of a wholesale spot market. The author indicates that these variables form the main factors that increase a country’s capacity to produce electricity and reduce its loss because of transmitting and distributing the nation’s power. Consequently, this implies that various reforms made at the national level regarding the policies and measures on electricity production, transmission, and distribution affect the countries’ economic development in diverse ways. Nagayama [14] also indicates that any country’s economic development impacts how it makes its reforms. Still, when a state coexists with independent regulatory agencies, such relations’ reforms lead to positive results in the power sector performance.

State regulators must also develop a divestiture policy. Divestiture can be viewed as the process of selling subsidiary businesses and their investments. Regulatory bodies at the state level can offer some companies financial incentives to induce them to sell their power plants [38]. However, state-level entities may order the companies just to quit the electricity business. Preferably, state-level entities should consider divestiture since it eliminates the possibility of a conflict of interest arising when companies can either decide to sell power from independent power producers (IPPs) or supply their facilities. State-level entities should consider working with companies that own no power plants since they have been shown to have the cheapest energy available in the market instead of those with power plants.

Additionally, state-level entities should develop strategies that would create mandated rate cuts. The main aim of introducing competition in the industry is to ensure that electricity price is reduced in the long run. Therefore, to ensure that electricity price is kept down, the regulators should introduce price cuts, thereby justifying consumers’ restructuring efforts [39]. However, regulators should consider various stakeholders’ views since price cuts can reduce incentives for consumers to move to another service provider, thereby discouraging investors and suppliers from entering the market.

Deregulation can also be successful if regulators can improve and maintain the power grid’s stability. Electricity has emerged as a utility resource and a security concern since the breakdown in electricity supply in the world today can lead to serious adverse effects, including loss of life [1]. However, electricity cannot be stored for future use and; therefore, companies should implement strategies to ensure the continuous provision of electricity. Some regulators at the state level have created Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs), which are responsible for adjusting electricity supply to ensure an equal change in demand. The development of these organizations is a significant step in providing regulation of the electricity market.

3.3. Effects of Deregulation on Prices

Based on reviewers’ feedback, this research expanded the literature evidence and analysis about the effects of deregulation on price, as it is a significant effect, enriching this study’s findings. Due to the process of deregulation, today’s electric power industry is undergoing many radical changes. Traditionally, in many countries, electrical power networks have been organized in a single vertically integrated organization to provide consumers with electrical power based on service costs. In recent years; however, many countries have adopted or are introducing a deregulated free-market sector. According to Wei-Jen Lee [40]: Within the energy industry and manufacturing networks’ operation, deregulation would have profound and substantial consequences for technology. Industrial sectors; therefore, need to re-evaluate possible impacts and operating strategies in a deregulated environment.

According to Burin [41], new opportunities for generating electricity have arisen to satisfy rising demand. The liberalization of many electricity markets worldwide has contributed to the global challenges of addressing the need for greater competitiveness in the supply of critical electrical infrastructure [42]. Another study shows that, regarding Brazil’s customers, there are two contracting models: The controlled system, in which contracts are set out through government decree; and the free environment, in which contracts are rendered freely by the parties concerned. When migrating from the controlled environment to the free environment becomes beneficial, customers should know how to do so. The study [43] seeks to understand how capitalist ideas have managed to capture room in the Brazilian economy’s leading thinking. According to the report, electricity sector transformations were driven by the business model’s crisis, which introduced the Brazilian hybrid model between 2003 and 2016.

According to Borenstein [44], the United States electric industry is estimated to be worth over USD 220 billion. For a long time, the industry has been referred to as the last great government-sanctioned monopoly. However, efforts to deregulate the industry have been implemented in various states. Advocates who support deregulation have claimed that it would lower the price of electricity and expand electricity services. The results obtained from multiple states that have enacted deregulation measures are; however, mixed. Deregulation has resulted in increased electricity prices, increased demand, and reduced supply. For example, electricity bills increased by 55% for Ameren customers in 2007, compared to 26% for Commonwealth Edison customers [44]. Although the resultant effects of deregulation on electricity prices have not been consistent, many regions that have implemented deregulation measures have experienced an increase in electricity prices in the short-term.

However, most studies showed a relationship between deregulation and the price of electricity. Implementing deregulation policies could be to reduce the price of electricity for households and companies [45]. However, most studies showed that electricity prices only reduced in the short run and reverted to the previous price in the long term. This can be attributed to the fact that numerous factors influence higher power prices, including the cost of production, connectivity issues, and changes in technology, among others. Therefore, changing legal policies and frameworks only reduces the price of power by a limited proportion.

On the other hand, publicly funded energy efficiency programs have grown in number, size, and scope in the past two decades. However, Horowitz [46] shows how combined effects of public programs have reduced commercial sector retail electricity sales. Another study [47] discusses the energy sector reform program in Ontario, Canada. Ontario’s retail and wholesale energy markets were opened to competition in 2002, with retail price levels that consumers had never previously encountered. In December 2002, the provincial government froze retail rates of electricity, covering approximately half of Ontario’s electricity consumption. While the weather played a significant role in driving prices, other factors such as market design problems, market rules, and market structure; also played an important role.

3.4. Effects of Deregulation on Opening-Up of the Market

Implementing deregulation policies has both positive and negative effects on the energy market. First, deregulation eliminates various entry barriers, allowing smaller companies to operate in the industry [48]. Removing entry barriers also fosters innovation, as smaller companies implement new technologies to compete effectively with larger companies. The free market created through deregulation sets the prevailing prices, thereby promoting growth.

Additionally, deregulation improves corporate efficiency as companies strive to attract more customers. Additionally, deregulation reduces the operational costs of the companies, thereby boosting their effectiveness. In the United States alone, regulation has cost USD 2 trillion [49]. Therefore, deregulation allows companies to invest their capital in plants and equipment instead of complying with federal rules. However, deregulation was viewed as having adverse effects on the industry due to various factors. First, deregulation exposes more customers to fraud and excessive risks as companies gain more freedom to make decisions, leading to reduced supervision. Deregulation also increases asset bubbles, which results in an increased risk of recessions and crises.

Most studies showed a positive relationship between deregulation and opening-up of the power market. Before deregulation, a limited number of companies operated the industry as countries implemented strict policies to restrict the number of organizations operating in the industry. However, deregulation opened the market by creating opportunities for other firms to operate in the sector to reduce power prices and increase connectivity. More firms have since invested in the industry, thereby reducing the pressure that existed in the industry due to the monopoly market.

Another study [50] presents benefits for integration in deregulated power markets. The wind energy system models depend on wind resources and the returns of the economic market. The paper focuses on identifying sub-problems such as the variability of the local power system and wind resource, which are challenging to model. However, wind energy cost models and market risk mitigation strategies can bring social impact and energy security compliance from large-scale wind integration.

Based on reviewers’ comments, this research focused on deregulation of other market structure types, such as distributed generation, which is becoming particularly crucial in the electricity system due to its high efficiency in processes, its low investment cost, modular capacity, and ability to take advantage of renewable resources. However, after reviewing the literature, the implementation of distributed generation in distribution networks could be complicated by various factors such as regulatory requirements, and lack of financially viable schemes. The complexities and risks in energy markets could further complicate the distributed generation planning, creating uncertainty in conventional planning methods.

3.5. Effects of Deregulation on Competitiveness

Deregulation has a significant relationship with competition. Deregulation creates opportunities for more companies to thrive in the industry; hence existing companies must develop unique strategies to ensure their survival [51]. Companies’ productivity increases when firms improve their performance, which only takes place when there is competition. Companies are obliged to renounce high rents and cut costs, thereby increasing their static efficiency. Static efficiency; however, boosts productivity only in the short-term. Long-term gains can only be guaranteed from dynamic efficiency [52]. Competition enhances dynamic ability in two main ways. First, competition increases the incentive to innovate. Firms operating in the electricity sector strive to adopt advanced technology to improve their performance. Secondly, competition accelerates creative destruction. Regulations and policies implemented in the energy sector regulate the entry of new firms into the industry. However, deregulation creates room for other companies, thereby increasing the knowledge pool. Therefore, firms can learn from each other and adopt similar strategies.

First, deregulation introduced stiff competition in the industry. In China, the State Power Corporation (SPC) controlled over 70% of the total energy production before the deregulation process [50]. However, after the deregulation process, SPC accounted for 40% of the total generation capacity, while other computing companies produced a different proportion. Deregulation led to an increase in independent power producers (IPPs), which were formed to boost power generation and enhance affordable connectivity. Some of the firms, formerly subsidiaries of SPC, transformed into listed shareholder companies to take advantage of the increased market for power.

Most studies considering the current research showed a positive relationship between deregulation policies and competition in the power sector. Deregulation is implemented to increase the number of players in the energy industry and transform it from a monopoly to a perfect competition market [53]. Therefore, in most cases, more than one company is engaged in producing and distributing power after implementing deregulation policies. The increase in firms operating in the power industry increases competition as each entity strives to increase its profitability and the number of customers they serve.

3.6. Effects of Deregulation on Innovation

Regulation of the electricity industry has revolutionized innovation, as companies operating in the industry strive to adopt new measures to enhance their competitive edge. Companies have adopted innovations through two significant factors [54]. First, companies’ innovativeness has increased in terms of input, whereby they have increased expenditure on research and development. Second, innovativeness is evidenced in output as companies have increased expenditure on patents.

Deregulation has also impacted the technologies used to generate and supply power. Due to deregulation measures, companies have resorted to advanced technologies to attract more customers and serve them better, thereby increasing their market share. For example, some companies operating in the power industry have been utilizing social media platforms to respond to customer inquiries and have launched mobile applications to carry out utility transactions. For example, Duke Energy, a significant player in the United States’ electricity industry, implemented Smart Meters [55]. By adopting Smart Meters, the company gave its customers access to more information concerning their household energy usage, thereby encouraging them to implement power-saving strategies. Additionally, Smart Meter technology enabled the company to monitor the grid in real-time and re-route power, reducing the chances of a power outage [56]. Additionally, digital smart-grid enabled the company to be more efficient since Smart Meters could be connected to renewable sources like wind and solar energy, thereby providing clean energy to customers.

Innovation aiming at advocating renewable sources of energy also received considerable attention. Deregulation aims at developing reliable, affordable, and clean energy for customers located in different parts of the country. For regulators to meet these standards, the parties involved must create innovative policies and measures to ensure that industry players consider the effects of deregulation on prices and cost efficiency [57]. Deregulation increases competitiveness and; therefore, companies operating in the industry view innovation as a tool to differentiate themselves from their rivals [30].

As evidenced by the articles reviewed, technology has been positively transformed because of deregulation. For example, Gao, H. [53] evaluated how deregulation has affected China’s electricity industry. According to the article, technology has transformed the landscape for utilities from generation to consumption of power. The study observed that deregulation had enabled power companies to venture into technologies related to power. For example, companies in the Chinese power industry have invented batteries that can be utilized in various activities, including load shifting, frequency regulation, and localized reserves.

None of the articles reviewed showed that deregulation had affected technology negatively.

3.7. Government and Political Environment in Support of Electricity Sector Deregulation.

The government is an essential agent in the political environment of the electricity sector deregulation. It could play an essential role environment in support of electricity sector deregulation in developed countries, economies in transition, and developing countries. After reviewing the literature, regarding the political agenda, some developing countries are still dependent on fossil fuels. Others have moved to hydroelectric power generation plants, and only a few cases are fostering renewable energy. However, some developing countries are deregulating the energy sector. It is evident from the literature that having an autonomous regulator with more stringent regulation is essential for developing countries to improve efficiency and ensure that producers and the government are not the only ones benefiting from privatization. On the other hand, since 1990, most developed countries began to deregulate their energy sector to focus on the market-oriented power sector. While most developed countries moved their political agenda away from fossil fuels and are adopting renewable energy, they have opened their market to the private sector and received investment to improve competitiveness, technology development, and innovation.

4. Conclusions

This article aimed to determining the economic effect of the deregulation of the energy sector on electricity. To achieve the research aim, the general objective was to analyze the relevant literature, evaluating the processes of deregulation policies, exploring the impacts of deregulation, analyzing the role of deregulation policies, and identify ways to improve the energy sector’s policies.

Citing and reviewing previous studies is the basis of this literature review and provides the analytical framework for this research. While the outcomes of studies are clarified and show the connectivity with other studies. The study findings must be seen considering limitations; there was a lack of prior studies on the soundness of scientific literature on the topic of energy reform, regulation, and energy sector deregulation.

Through a literature review, the study evaluated how deregulation has affected innovation, the creation of an open market, power prices, and competitiveness. In conclusion, reforms in the energy sector rely heavily on the nation’s politics, initial conditions of power transformation, and policies that guide such changes, technological states, and focusing on the most critical sectors of the economy without ignoring those perceived to be less significant.

Deregulation in the power sector can be viewed as measures implemented by regulation agencies like government entities to remove restrictions, thereby increasing competition in the market and decreasing the cost of power for consumers. Technology plays a significant role in deregulation efforts, as entities that operate in the industry after implementing the deregulation measures strive to adopt new and advanced technologies to enhance their competitiveness. Various countries worldwide have been implementing deregulation policies to stabilize electricity prices and distribute powers to a few entities that regulate power connectivity.

A systematic review approach was adopted, whereby qualitative and quantitative studies were analyzed. The results showed that most of the studies proved that deregulation policies have increased competition in the market by creating an opportunity for other companies to enter the sector. Additionally, it was evident that regulation has resulted in increased innovativeness as firms develop new ideas and policies to thrive in the competitive market. The results also showed that deregulation had opened the market by encouraging more investors to venture into the industry and attracting start-up companies involved in at least one of the power production processes or connectivity. However, regarding prices, the research showed that deregulation policies do not guarantee a reduction in prices. Most of the time, power price reduction occurs in the long run instead of the short run.

The results also showed that government-led deregulation policies are more effective than systemic-led or market-led interventions. Therefore, for the government policies to be effective, it is recommended that the government collaborate with other stakeholders in the energy sector.

On the other hand, the results indicate that cross-subsidies and pricing mechanisms changed on implementing reforms. The main reason for changes in pricing is the implementation of a regulating policy on tariff rationalization. Market-based measures are not yet as effective, which involves several changes before competitive elements become an integral part. The results also revealed that changes due to the deregulation had increased the efficiency and profitability in this area, even though productivity gains generally may not reach the end-users. It is evident from the literature that having an autonomous regulator with more stringent regulation is essential for developing countries to improve efficiency and ensure that producers and the government are not the only ones benefiting from privatization. Concerning this, in the policy’s implementation, the government should create an autonomous regulator and tariff rationalization for deregulation policies’ positive impact. In addition to this, the deregulation policy needs to be deciphered considering how the government has partnerships working to invest resources in organizing appropriations and provide incentives for state governments to achieve specific predefined goals.

It has been found that electricity reforms cause poverty alleviation precisely when the poor have access to electricity. This suggests that reforms must be limited to meet the poor’s energy needs, which could improve the poor’s welfare. Nevertheless, to cater to the policy’s poor energy needs, the nature of the regulation plays a crucial role. Therefore, the policy regulation and regulatory framework should strike a balance between the economic efficiency and equity impact of deregulation policy.

In the future, further research can be carried out to investigate further the development of the framework for public deregulation policy. The results obtained can be utilized by various stakeholders in the energy sector, including power companies, policymakers, and government officials responsible for energy. Furthermore, this article only provides an assessment of the economic impacts of deregulation. Therefore, considering this research, in the future, more research can be conducted to analyze the impact of deregulation on other aspects such as the environment. Future research would be relevant to evaluate further the necessary measures that should be implemented to guarantee a reduction in power prices after deregulation is carried out.

Author Contributions

P.D.N.-P., A.L. and J.C.S.-E. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Evidence Studies

| Alcázar, L.; Nakasone, E.; Torero, M. Provision of Public Services and Welfare of the Poor: Learning from an Incomplete Electricity Privatization Process in Rural Peru; Research Network Working Paper No. R-526; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B. |

| Andres, L.; Guasch, J.L.; Lopez Azumendi, S. Regulatory Governance and Sector Performance: Methodology and Evaluation for Electricity Distribution in Latin America; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. |

| Babatunde, M.A. Keeping the Lights on in Nigeria: Is Power Sector Reform Sufficient? J. Afr. Bus. 2011, 12, 368–386, doi:10.1080/15228916.2011.621826. |

| Bhattacharyya, S.C. Power sector reform in South Asia: Why slow and limited so far? Energy Policy 2007, 35, 317–332, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2005.11.028 |

| Burin, H.P.; Siluk, J.S.; Rediske, G.; Rosa, C.B. Determining Factors and Scenarios of Influence on Consumer Migration from the Regulated Market to the Deregulated Electricity Market. Energies 2021, 14, 65 |

| Campos, A.F.; da Silva, N.F.; Pereira, M.G.; Siman, R.R. Deregulation, flexibilization and privatization: Historical and critical perspective of the Brazilian electric sector. Electr. J. 2020, 33, 106796. |

| Chatterjee, E. The politics of electricity reform: Evidence from West Bengal, India. World Dev. 2018, 104, 128–139, doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.003. |

| Chinmoy, L.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. Modeling wind power investments, policies and social benefits for deregulated electricity market—A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 364–377. |

| Chong, A.; López-De-Silanes, F. Privatization in Latin America: What Does the Evidence Say? Economía 2004, 4, 37–111, doi:10.1353/eco.2004.0013. |

| Dornan, M. Reform despite politics? The political economy of power sector reform in Fiji, 1996–2013. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 703–712, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.11.070. |

| Du, L.; Mao, J.; Shi, J. Assessing the impact of regulatory reforms on China’s electricity generation industry. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 712–720, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.083 |

| Eberhard, A.; Gratwick, K.; Morella, E.; Antmann, P. Independent Power Projects in Sub-Saharan Africa: Investment trends and policy lessons. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 390–424, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.023. |

| Edomah, N. Modelling Future Electricity: Rethinking the Organizational Model of Nigeria’s Electricity Sector. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 27074–27080, doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2769338. |

| Estache, A.; Rossi, M.A. Do regulation and ownership drive the efficiency of electricity distribution? Evidence from Latin America. Econ. Lett. 2005, 86, 253–257, doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2004.07.016. |

| Gao, H.; van Biesebroeck, J. Effects of Deregulation and Vertical Unbundling on the Performance of China’s Electricity Generation Sector. J. Ind. Econ. 2014, 62, 41–76, doi:10.1111/joie.12034. |

| Han, W.; Jiang, K.; Fan, L. Reform of China’s electric power industry: facing the market and competition. Int. J. Glob. Energy Issues 2005, 23, 188, doi:10.1504/ijgei.2005.006887. |

| Horowitz, M. Electricity Intensity in the Commercial Sector: Market and Public Program Effects. Energy J. 2004, 25, 115–137. |

| Kapika, J.; Eberhard, A. Power-Sector Reform and Regulation in Africa; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. |

| Kayo, D. Power sector reforms in Zimbabwe: Will reforms increase electrification and strengthen local participation? Energy Policy 2002, 30, 959–965, doi:10.1016/s0301-4215(02)00050-2. |

| Khan, A.J. The Comparative Efficiency of Public and Private Power Plants in Pakistan’s Electricity Industry. Lahore J. Econ. 2014, 19, 1–26, doi:10.35536/lje.2014.v19.i2.a1. |

| Malgas, I.; Eberhard, A. Hybrid power markets in Africa: Generation planning, procurement and contracting challenges. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3191–3198, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.004 |

| Millán, J. Power sector reform in Latin America: Accomplishments, failures and challenges. Econ. Political Wkly. 2005, 5291–5301. |

| Nagayama, H. Impacts on investments, and transmission/distribution loss through power sector reforms. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3453–3467, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.02.019. |

| Nagayama, H.; Kashiwagi, T. Evaluating electricity sector reforms in Argentina: Lessons for developing countries? J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 115–130, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.11.056. |

| Nair, S. Electricity Regulation in India. Margin: J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2008, 2, 87–144, doi:10.1177/097380100700200103. |

| Nepal, R.; Jamasb, T. Reforming small electricity systems under political instability: The case of Nepal. Energy Policy 2012, 40, 242–251. |

| Orion, B. Transmission in Transition: Analyzing California’s Proposed Electricity Transmission Regulatory Reforms. Hastings LJ 2004, 56, 343. |

| Pineau, P.O. Transparency in the dark: An assessment of the Cameroonian electricity sector reform. Int. J. Glob. Energy Issues 2005, 23, 133, doi:10.1504/ijgei.2005.006875. |

| Pollitt, M. Electricity reform in Argentina: Lessons for developing countries. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 1536–1567, doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2007.12.012. |

| Pollitt, M. Electricity Reform in Chile. Lessons for Developing Countries. Compet. Regul. Netw. Ind. 2004, 5, 221–262, doi:10.1177/178359170400500301. |

| Trebilcock, M.; Hrab, R. Electricity Restructuring in Ontario. Energy J. 2005, 26, 123–146. |

| Lee, W.-J.; Lin, C.H.; Swift, K.D. Wheeling charge under a deregulated environmentsustainability-110844. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2001, 37, 178–183, doi:10.1109/28.903144. |

| Williams, J.; Ghanadan, R. Electricity reform in developing and transition countries: A reappraisal. Energy 2006, 31, 815–844, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2005.02.008. |

| Wren-Lewis, L. Do Infrastructure Reforms Reduce the Effect of Corruption? Theory and Evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2013, 29, 353–384, doi:10.1093/wber/lht027. |

| Zhang, Y.F.; Parker, D.; Kirkpatrick, C. Competition, regulation and privatisation of electricity generation in developing countries: Does the sequencing of the reforms matter? Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2005, 45, 358–379, doi:10.1016/j.qref.2004.12.009. |

References

- Urpelainen, J.; Yang, J. Global patterns of power sector reform, 1982–2013. Energy Strat. Rev. 2019, 23, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden-Schilling, C. The infrastructure of markets: From electric power to electronic data. Econ. Anthr. 2016, 3, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Alsafasfeh, Q.; Pourbabak, H.; Su, W. The Next-Generation U.S. Retail Electricity Market with Customers and Prosumers—A Bibliographical Survey. Energies 2017, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofala, J. Energy reform in Central and Eastern Europe. Energy Policy 1994, 22, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockschink, S.R.; Gurney, J.H.; Seely, D.B. Hydroelectric power generation. In Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coricelli, F.; Cukierman, A.; Dalmazzo, A. Monetary institutions, monopolistic competition, unionized labor markets and economic performance. Scand. J. Econ. 2006, 108, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, H.; Zolezzi, J. Electric sector deregulation and restructuring in Latin America: Lessons to be learnt and possible ways forward. IEEE Proc. Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2001, 148, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orion, B. Transmission in Transition: Analyzing California’s Proposed Electricity Transmission Regulatory Reforms. Hastings LJ 2004, 56, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Schuelke-Leech, B.-A.; Barry, B.; Muratori, M.; Yurkovich, B. Big Data issues and opportunities for electric utilities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Parker, D.; Kirkpatrick, C. Competition, regulation and privatisation of electricity generation in developing countries: Does the sequencing of the reforms matter? Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2005, 45, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S. Electricity Regulation in India. Margin J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2008, 2, 87–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Parker, D.; Kirkpatrick, C. Electricity sector reform in developing countries: An econometric assessment of the effects of privatization, competition and regulation. J. Regul. Econ. 2008, 33, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, M. Electricity reform in Argentina: Lessons for developing countries. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 1536–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, H. Impacts on investments, and transmission/distribution loss through power sector reforms. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3453–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, F.R.; Ramalho, E.; Andrade, M.; Cortez, L. Privatisation of the Brazilian electricity industry: Opportunities and pitfalls. Int. J. Glob. Energy Issues 2002, 17, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioppolo, G.; Cucurachi, S.; Salomone, R.; Saija, G.; Shi, L. Sustainable Local Development and Environmental Governance: A Strategic Planning Experience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K. Restructuring and Performance in India’s Electricity Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama, H.; Kashiwagi, T. Evaluating electricity sector reforms in Argentina: Lessons for developing countries? J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, E.K. Political Economy of Nigerian Power Sector Reform. In The Political Economy of Clean Energy Transitions; Arent, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Pineau, P.-O. How sustainable is policy incoherence? A rationalist policy analysis of the Cameroonian electricity reform. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Kishawy, H.A. Sustainable Manufacturing and Design: Concepts, Practices and Needs. Sustainability 2012, 4, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.Ø.; D’haen, S.A.L. Asking about climate change: Reflections on methodology in qualitative climate change research published in Global Environmental Change since Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.M. The Politics, Fashions, and Conventions of Research Methods. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2011, 5, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songvilay, L.; Insisienmay, S.; Turner, M. Trial and Error in State-Owned Enterprise Reform in Laos. Asian Perspect. 2017, 41, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, D.G. The Effects of Power Sector Reform on Energy Services for the Poor; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Ghanadan, R. Electricity reform in developing and transition countries: A reappraisal. Energy 2006, 31, 815–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, A.; Gratwick, K.; Morella, E.; Antmann, P. Independent Power Projects in Sub-Saharan Africa: Investment trends and policy lessons. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 390–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.; López-De-Silanes, F. Privatization in Latin America: What Does the Evidence Say? Economía 2004, 4, 37–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kayo, D. Power sector reforms in Zimbabwe: Will reforms increase electrification and strengthen local participation? Energy Policy 2002, 30, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.; Jamasb, T. Reforming small electricity systems under political instability: The case of Nepal. Energy Policy 2011, 40, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, C.K.; Sen, S.; Paul, A.K.; Acharya, K. First Report of Alternaria dianthicola Causing Leaf Blight on Withania somnifera from India. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Eiras, M.; Rossi, M.A. The Impact of Electricity Sector Privatization on Public Health. SSRN Electron. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Klausner, M.D.; Litvak, K. What Economists Have Taught Us About Venture Capital Contracting. SSRN Electron. J. 2001, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, J.; Goto, M.; Inoue, K. Do acquisitions by electric utility companies create value? Evidence from deregulated markets. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, D. Electricity Sector Deregulation in the APEC Region; Asia-Pacific Energy Research Center, Institute of Energy Eco-Nomics: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gholizad, A.; Ahmadi, L.; Hassannayebi, E.; Memarpour, M.; Shakibayifar, M. A System Dynamics Model for the Analysis of the Deregulation in Electricity Market. Int. J. Syst. Dyn. Appl. 2017, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Saurabh, S.; Shrivastava, L.; Gaur, A.K. Renewable energy based on deregulated electricity market. Energy 2017, 50, 15–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vestlund, N.M. Pooling administrative resources through EU regulatory networks. J. Eur. Public Policy 2015, 24, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.K.; Pal, M.S. A Literature Review on Bidding Strategy in a Deregulated Electricity Market. IJRTI 2018, 3, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-J.; Lin, C.H.; Swift, K.D. Wheeling charge under a deregulated environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2001, 37, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, H.P.; Siluk, J.S.M.; Rediske, G.; Rosa, C.B. Determining Factors and Scenarios of Influence on Consumer Migration from the Regulated Market to the Deregulated Electricity Market. Energies 2020, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edomah, N. Modelling Future Electricity: Rethinking the Organizational Model of Nigeria’s Electricity Sector. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 27074–27080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.F.; Da Silva, N.F.; Pereira, M.G.; Siman, R.R. Deregulation, flexibilization and privatization: Historical and critical perspective of the brazilian electric sector. Electr. J. 2020, 33, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, S.; Bushnell, J. The US Electricity Industry after 20 Years of Restructuring. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2015, 7, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.J.; Managi, S. Liberalization of a retail electricity market: Consumer satisfaction and household switching behavior in Japan. Energy Policy 2017, 110, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M. Electricity Intensity in the Commercial Sector: Market and Public Program Effects. Energy J. 2004, 25, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebilcock, M.J.; Hrab, R. Electricity Restructuring in Ontario. Energy J. 2005, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovtchinnikov, A.V. Debt decisions in deregulated industries. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 36, 230–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, S. When does regulation distort costs? Lessons from fuel procurement in us electricity generation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 411–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinmoy, L.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. Modeling wind power investments, policies and social benefits for deregulated electricity market—A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, Y.; Arango-Aramburo, S.; Larsen, E.R. How capacity mechanisms drive technology choice in power generation: The case of Colombia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camejo, R.R.; Miraldo, M.; Rutten, F. Cost-Effectiveness and Dynamic Efficiency: Does the Solution Lie Within? Value Health 2017, 20, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gao, H.; Van Biesebroeck, J. Effects of Deregulation and Vertical Unbundling on the Performance of China’s Electricity Generation Sector. J. Ind. Econ. 2014, 62, 41–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Parrotta, P.; Valletta, G. Electricity (de)regulation and innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, V.C.; Sahin, D.; Kocak, T.; Ergut, S.; Buccella, C.; Cecati, C.; Hancke, G.P. Smart Grid and Smart Homes: Key Players and Pilot Projects. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2012, 6, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hong, T.; Kang, C. Review of Smart Meter Data Analytics: Applications, Methodologies, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 3125–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.; Al-Arfaj, K.; Paudyal, K. Modelling generator maintenance scheduling costs in deregulated power markets. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).